Official Development Assistance and Private Voluntary Support for Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Health in Guinea-Bissau: Assessing Trends and Effectiveness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Gathering

2.3. Data Disbursement Classification

2.4. Data Estimations and Coding

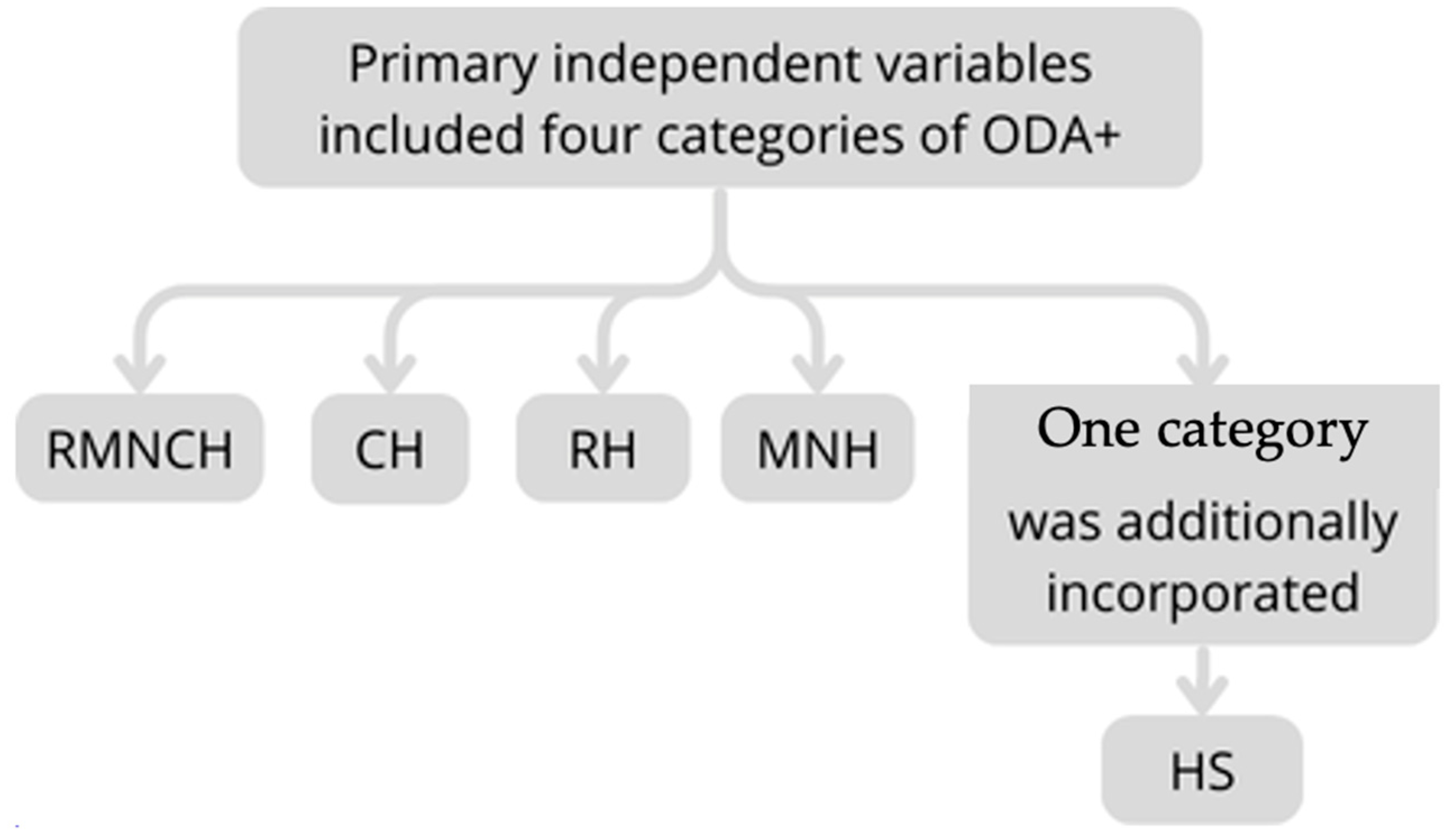

2.5. Data Categorization and Study Variables

2.5.1. Data Categorization

2.5.2. Study Variables

2.6. Data Modelling and Analysis

2.6.1. Study Hypothesis

2.6.2. Model Development

2.6.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

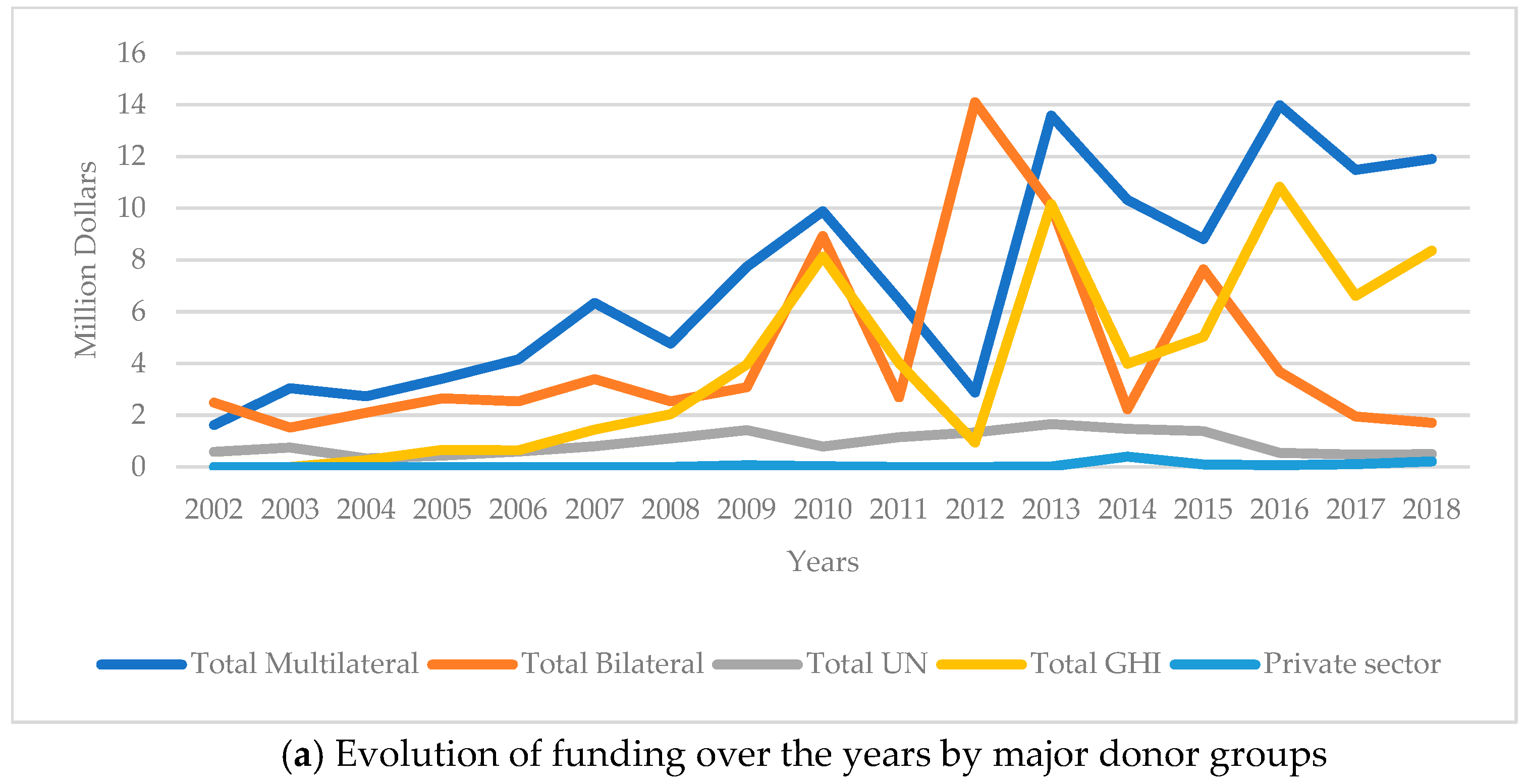

3.1. Flows of ODA+ Funding in Guinea-Bissau

3.2. Donor Variability and Growth Rates

3.3. RMNCH-Specific Funding Allocation

3.4. Child Health Funding

3.5. Maternal and Neonatal Health Funding

3.6. Reproductive Health Funding

3.7. ODA+ Funding Allocation

3.8. Funding and Mortality Trends

3.9. Aid Measures and Mortality Rate Associations

4. Discussion

4.1. Trends RMNCH Funding

4.2. RMNCH Funding and Mortality Rates

4.3. Donor Contributions and Funding Variability

4.4. Influence of Socioeconomic Factors on Mortality Reduction

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Rahman, M.; Rouyard, T.; Khan, S.T.; Nakamura, R.; Islam, R.; Hossain, S.; Akter, S.; Lohan, M.; Ali, M.; Sato, M. Reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health intervention coverage in 70 low-income and middle-income countries, 2000–30: Trends, projections, and inequities. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e1531–e1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchant, T.; A Bhutta, Z.; Black, R.; Grove, J.; Kyobutungi, C.; Peterson, S. Advancing measurement and monitoring of reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health and nutrition: Global and country perspectives. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4 (Suppl. S4), e001512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Public Spending on Health: A Closer Look at Global Trends; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Targets of Sustainable Development Goal 3. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/about-us/our-work/sustainable-development-goals/targets-of-sustainable-development-goal-3 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Costello, A.; Naimy, Z. Maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health: Challenges for the next decade. Int. Health 2019, 11, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engmann, C.M.; Khan, S.; Moyer, C.A.; Coffey, P.S.; Bhutta, Z.A. Transformative Innovations in Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Health over the Next 20 Years. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1001969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. DAC Glossary of Key Terms and Concepts. 2019. Available online: https://web-archive.oecd.org/2024-02-22/66749-dac-glossary.htm (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Staicu, G.; Barbulescu, R. A Study of the Relationship between Foreign Aid and Human Development in Africa. In International Development; InTech: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R.; Zeeshan Haque, M.I.; Gupta, N.; Tausif, M.R.; Kaushik, I. How foreign aid and remittances affect poverty in MENA countries? PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D. The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time; Penguin Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Easterly, W. Was Development Assistance a Mistake? Am. Econ. Rev. 2007, 97, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, D. Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Toseef, M.U.; Jensen, G.A.; Tarraf, W. How Effective is Foreign Aid at Improving Health Outcomes in Recipient Countries? Atl. Econ. J. 2019, 47, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, C.R. Foreign Aid and Human Development: The Impact of Foreign Aid to the Health Sector. South Econ J. 2008, 75, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leunig, I.; Dijkstra, G.; Tuytens, P. The Relationship Between Health aid and Health Outcomes and the Role of Domestic Healthcare Expenditure in Developing Countries. Forum Dev. Stud. 2024, 51, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, R.; Dolan, C.B.; Leu, M.; Runfola, D. Taking the health aid debate to the subnational level: The impact and allocation of foreign health aid in Malawi. BMJ Glob. Health 2017, 2, e000129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, A.; Lang, V.; Reinsberg, B. Aid effectiveness and donor motives. World Dev. 2024, 176, 106501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, P.; Moreira, S.B.; Caiado, J. Identifying differences and similarities between donors regarding the long-term allocation of official development assistance. Dev. Stud. Res. 2021, 8, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, B. From Aid to Development. 2012. (OECD Insights). Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/agriculture-and-food/development-and-aid_9789264123571-en (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Elayah, M.; Al-Awami, H. Exploring the preference for bilateral aid: Gulf oil states’ aid to Yemen. Third World Q. 2024, 45, 2266–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apodaca, C. Foreign Aid as Foreign Policy Tool. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; Available online: http://politics.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-332 (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- United Nations D of E and SAPD. World Population Prospects 2024, Online Edition. 2024. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/downloads?folder=Standard%20Projections&group=Most%20used (accessed on 4 August 2024).

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). Human Development Report 2023/2024: Breaking the Gridlock—Reimagining Cooperation in a Polarized World; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sangreman, C. A Política Económica e Social na Guiné-Bissau. CEsA/CSG—Documentos de Trabalho no 146/2016; ISEG-CEsA/CSG: Lisboa, Portugal, 2016; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- De Barros, M.; Gomes, P.G.; Correia, D. Les conséquences du narcotrafic sur un État fragile: Le cas de la Guinée-Bissau. Altern. Sud 2013, 20, 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, M. Drug trafficking in Guinea-Bissau, 1998–2014: The evolution of an elite protection network. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2015, 53, 339–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME). Levels and Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2024; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. World Development Indicators. 2024. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 4 August 2024).

- Patel, P.; Roberts, B.; Guy, S.; Lee-Jones, L.; Conteh, L. Tracking Official Development Assistance for Reproductive Health in Conflict-Affected Countries. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Tadesse, E.; Jin, Y.; Cha, S. Association between Development Assistance for Health and Disease Burden: A Longitudinal Analysis on Official Development Assistance for HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria in 2005–2017. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Aid Transparency Initiative. The Relationship Between IATI and CRS. 2025. Available online: https://iatistandard.org/documents/63/The-relationship-between-IATI-and-CRS.doc (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Dingle, A.; Schäferhoff, M.; Borghi, J.; Lewis Sabin, M.; Arregoces, L.; Martinez-Alvarez, M.; Pitt, C. Estimates of aid for reproductive, maternal, neonatal, and child health: Findings from application of the Muskoka2 method, 2002–2017. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e374–e386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, C.; Bath, D.; Binyaruka, P.; Borghi, J.; Martinez-Alvarez, M. Falling aid for reproductive, maternal, neonatal and child health in the lead-up to the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e006089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Frequently Asked Questions on Official Development Assistance. 2024. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/insights/data-explainers/2024/07/frequently-asked-questions-on-official-development-assistance-oda.html (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- OECD. Aid to Health. 2018. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/development/stats/aidtohealth.htm (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Hsu, J.; Berman, P.; Mills, A. Reproductive health priorities: Evidence from a resource tracking analysis of official development assistance in 2009 and 2010. Lancet 2013, 381, 1772–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell-Jackson, T.; Borghi, J.; Mueller, D.H.; Patouillard, E.; Mills, A. Countdown to 2015: Tracking donor assistance to maternal, neonatal, and child health. Lancet 2006, 368, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs UN. World Population Prospects 2019. 2021. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD Results Tool. 2019. Available online: https://www.healthdata.org/data-tools-practices/interactive-visuals/gbd-results (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- OECD. Creditor Reporting System: Aid activities. OECD International Development Statistics (Database). 2024. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/data/creditor-reporting-system/aid-activities_data-00061-en (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel, Version 16; Microsoft Corporation: Redmond, WA, USA, 2016.

- UNICEF; WHO. A Decade of Tracking Progress for Maternal, Newborn and Child Survival: The 2015 Report. 2015. Available online: https://www.countdown2015mnch.org/documents/2015Report/Countdown_to_2015_final_report.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- WHO. World Health Statistics 2024. 2024. Available online: https://data.who.int (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Winkleman, T.F.; Adams, G.B. An empirical assessment of the relationship between Official Development Aid and child mortality, 2000–2015. Int. J. Public Health 2017, 62, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banchani, E.; Swiss, L. The Impact of Foreign Aid on Maternal Mortality. Politics Gov. 2019, 7, 53–67. Available online: https://www.cogitatiopress.com/politicsandgovernance/article/view/1835 (accessed on 23 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- StataCorp LLC. Stata Statistical Software, Release 18; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2023.

- Boundioa, J.; Thiombiano, N. Effect of public health expenditure on maternal mortality ratio in the West African Economic and Monetary Union. BMC Womens Health 2024, 24, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, J.P.; Day, L.T.; Rezende-Gomes, A.C.; Zhang, J.; Mori, R.; Baguiya, A.; Jayaratne, K.; Osoti, A.; Vogel, J.P.; Campbell, O.; et al. A global analysis of the determinants of maternal health and transitions in maternal mortality. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e306–e316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan, K. We the Peoples: The Role of the United Nations in the 21st Century; United Nations Department of Public Information: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Countdown to 2015. Fulfilling the Health Agenda for Women and Children. 2014. Available online: https://www.countdown2030.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Countdown_2014_Report_No_Profiles_final.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Kirton, J.; Kulik, J.; Bracht, C. The political process in global health and nutrition governance: The G8’s 2010 Muskoka Initiative on Maternal, Child, and Neonatal Health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1331, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UKAid. The London Summit on Family Planning. 2012. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/67328/london-summit-family-planning-commitments.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- United Nations. Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, G.; Powell-Jackson, T.; Borghi, J.; Mills, A. Countdown to 2015: Assessment of donor assistance to maternal, neonatal, and child health between 2003 and 2006. Lancet 2008, 371, 1268–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grollman, C.; Arregoces, L.; Martínez-Álvarez, M.; Pitt, C.; Mills, A.; Borghi, J. 11 years of tracking aid to reproductive, maternal, neonatal, and child health: Estimates and analysis for 2003–2013 from the Countdown to 2015. Lancet Glob. Health 2017, 5, e104–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, Z.A.; Lassi, Z.S.; Blanc, A.; Donnay, F. Linkages Among Reproductive Health, Maternal Health, and Perinatal Outcomes. Semin. Perinatol. 2010, 34, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, O.; McClure, E.M.; Wright, L.L.; Saleem, S.; Goudar, S.S.; Chomba, E.; Patel, A.; Esamai, F.; Garces, A.; Althabe, F.; et al. A combined community- and facility-based approach to improve pregnancy outcomes in low-resource settings: A Global Network cluster randomized trial. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.; Pitt, C.; Greco, G.; Berman, P.; Mills, A. Countdown to 2015: Changes in official development assistance to maternal, neonatal, and child health in 2009–2010, and assessment of progress since 2003. Lancet 2012, 380, 1157–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kibira, D.; Asiimwe, C.; Muwonge, M.; van den Ham, H.A.; Reed, T.; Leufkens, H.G.; Mantel-Teeuwisse, A.K. Donor Commitments and Disbursements for Sexual and Reproductive Health Aid in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. Front. Public Health. 2021, 9, 645499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grépin, K.A.; Pinkstaff, C.B.; Hole, A.R.; Henderson, K.; Norheim, O.F.; Røttingen, J.A.; Ottersen, T. Allocating external financing for health: A discrete choice experiment of stakeholder preferences. Health Policy Plan. 2018, 33 (Suppl. S1), i24–i30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottersen, T.; Kamath, A.; Moon, S.; Martinsen, L.; Røttingen, J.A. Development assistance for health: What criteria do multi- and bilateral funders use? Health Econ. Policy Law 2017, 12, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottersen, T.; Grépin, K.A.; Henderson, K.; Pinkstaff, C.B.; Norheim, O.F.; Røttingen, J.A. New approaches to ranking countries for the allocation of development assistance for health: Choices, indicators and implications. Health Policy Plan. 2018, 33 (Suppl. S1), i31–i46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chersich, M.F.; Martin, G. Priority gaps and promising areas in maternal health research in low- and middle-income countries: Summary findings of a mapping of 2292 publications between 2000 and 2012. Glob. Health 2017, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.K. Addressing reproductive and maternal health in Latin America and the caribbean—Initiatives underway. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. J. 2018, 9, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Accra Agenda for Action; OECD: Paris, France, 2008; Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/accra-agenda-for-action_9789264098107-en (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- OECD. Declaration of the Fourth High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness. 2011. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/development/effectiveness/49650173.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- General Assembly UN. General Assembly. 2019. Available online: https://www.un.org/pga/73/wp-content/uploads/sites/53/2019/07/FINAL-draft-UHC-Political-Declaration.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- Fuller, J.A.; Villamor, E.; Cevallos, W.; Trostle, J.; Eisenberg, J.N. I get height with a little help from my friends: Herd protection from sanitation on child growth in rural Ecuador. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmush, B.L.; Walia, B.; Neupane, A.; Frances, C.; Mohamed, I.A.; Iqbal, M.; Larsen, D.A. Community-level impacts of sanitation coverage on maternal and neonatal health: A retrospective cohort of survey data. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e005674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ummalla, M.; Samal, A.; Zakari, A.; Lingamurthy, S. The effect of sanitation and safe drinking water on child mortality and life expectancy: Evidence from a global sample of 100 countries. Aust. Econ. Pap. 2022, 61, 778–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.S. Investigating The Importance of Vaccines and Childhood Nutrition on Improving Maternal and Child Health. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 7, 10275–10277. Available online: https://ijmrset.com/upload/111_Investigating.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Karaut, T.S. Evaluating the Effectiveness and Coverage of Vaccination Programs in Reducing the Incidence of Paediatric Infectious Diseases. Asian J. Pediatr. Res. 2024, 14, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishai, D.M.; Cohen, R.; Alfonso, Y.N.; Adam, T.; Kuruvilla, S.; Schweitzer, J. Factors Contributing to Maternal and Child Mortality Reductions in 146 Low- and Middle-Income Countries between 1990 and 2010. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0144908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bijleveld, P.; Maliqi, B.; Pronyk, P.; Franz-Vasdeki, J.; Nemser, B.; Sera, D.; van de Weerdt, R.; Walter, B. Country perspectives on integrated approaches to maternal and child health: The need for alignment and coordination. Bull. World Health Organ. 2016, 94, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Reproductive Health (RH) | Activities focused on reproductive and sexual health for non-pregnant women, including family planning and population policies [32,36]. |

| Maternal and Neonatal Health (MNH) | Interventions focused on the health of pregnant women and their newborns during pregnancy, childbirth, and the one-month postnatal period [32,37]. |

| Child Health (CH) | Activities aimed at improving children’s health from one month to five years [32,37]. |

| Model | Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | Control Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Neonatal mortality | HS | GDP per capita, DTP and measles coverage, life expectancy, sanitation, fertility rate |

| 2 | Infant mortality | HS | GDP per capita, DTP and measles coverage, life expectancy, sanitation |

| 3 | Under-5 mortality | HS | Same as Model 2 |

| 4 | Maternal mortality | HS | GDP per capita, fertility rate |

| 5 | Neonatal mortality | RMNCH | Same as Model 1 |

| 6 | Infant mortality | RMNCH | Same as Model 2 |

| 7 | Under-5 mortality | RMNCH | Same as Model 2 |

| 8 | Maternal mortality | RMNCH | Same as Model 4 |

| 9 | Neonatal mortality | CH | Same as Model 1 |

| 10 | Infant mortality | CH | Same as Model 2 |

| 11 | Under-5 mortality | CH | Same as Model 2 |

| 12 | Neonatal mortality | RH | Same as Model 1 |

| 13 | Maternal mortality | RH | Same as Model 4 |

| 14 | Neonatal mortality | MNH | Same as Model 1 |

| 15 | Maternal mortality | MNH | Same as Model 4 |

| Dependent Variables | Min. | Mean | Median | Máx. | SD | Annual Average Trend | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal mortality | 36.70 | 45.08 | 45.10 | 53.20 | 5.58 | ↓ 2.29% | 17 |

| Infant mortality | 54.60 | 74.48 | 72.60 | 99.50 | 14.72 | ↓ 3.68% | 17 |

| Under-five mortality | 82.40 | 118.01 | 114.40 | 163.40 | 26.50 | ↓ 4.19% | 17 |

| Maternal mortality | 648.00 | 830.59 | 795.00 | 1136.00 | 145.23 | ↓ 3.38% | 17 |

| Funding (US $, Millions, 2018) | |||||||

| ODA+ all sectors | 77.27 | 130.74 | 113.07 | 273.83 | 50.56 | ↑15.84% | 17 |

| ODA+ Health | 8.71 | 21.43 | 19.89 | 40.15 | 31.44 | ↑ 13.83% | 17 |

| ODA+ RMNCH | 4.10 | 11.61 | 10.89 | 23.69 | 5.78 | ↑ 14.83% | 17 |

| ODA+ CH | 1.90 | 6.51 | 4.94 | 15.10 | 3.84 | ↑ 23.46% | 17 |

| ODA+ RH | 0.53 | 1.94 | 1.50 | 4.77 | 1.40 | ↑ 33.18% | 17 |

| ODA+ MNH | 1.34 | 3.17 | 2.53 | 8.03 | 1.87 | ↑ 17.24% | 17 |

| Control variables | |||||||

| GDP per capita | 1600.65 | 1703.08 | 1690.09 | 1872.31 | 84.58 | ↑ 0.83 | 17 |

| Average life expectancy at birth | 50.98 | 55.98 | 56.23 | 60.50 | 3.19 | ↑ 1.08 | 17 |

| Basic sanitation rate (%) | 3.01 | 7.88 | 7.80 | 3.20 | 13.03 | ↑ 11.11 | 17 |

| Fertility rate | 4.26 | 5.61 | 5.06 | 5.06 | 0.42 | ↓1.70 | 17 |

| Modern contraception (%) | 0.059 | 0.098 | 0.094 | 0.154 | 0.031 | ↑ 6.20 | 17 |

| Measles vaccination (%) | 66.00 | 76.00 | 76.00 | 83.00 | 4.78 | ↑ 0.78 | 17 |

| DTP vaccination coverage (%) | 57.00 | 77.18 | 80.00 | 87.00 | 9.89 | ↑ 2.36 | 17 |

| Year | RMNCH | AAGR (%) | RH | AAGR (%) | CH | AAGR (%) | MNH | AAGR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 4.1 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 1.3 | ||||

| 2003 | 4.6 | 11.4 | 0.7 | 22.8 | 2.5 | 29.9 | 1.4 | 7.2 |

| 2004 | 4.8 | 5.7 | 0.5 | 21.2 | 2.9 | 15.5 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| 2005 | 6.1 | 25.6 | 0.9 | 73.9 | 3.3 | 15.4 | 1.9 | 28.0 |

| 2006 | 6.7 | 10.3 | 1.5 | 63.8 | 3.3 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 0.8 |

| 2007 | 9.7 | 45.6 | 2.3 | 50.8 | 5.0 | 49.5 | 2.5 | 34.5 |

| 2008 | 7.3 | 24.9 | 1.7 | 25.2 | 3.7 | 24.7 | 1.9 | 25.0 |

| 2009 | 10.9 | 48.9 | 4.8 | 181.7 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 2.2 | 17.7 |

| 2010 | 18.9 | 73.2 | 4.6 | 3.1 | 9.3 | 137.9 | 5.0 | 123.5 |

| 2011 | 9.2 | 51.5 | 3.0 | 34.4 | 3.8 | 59.4 | 2.4 | 52.6 |

| 2012 | 17.0 | 85.5 | 1.3 | 58.5 | 9.5 | 153.8 | 6.2 | 161.5 |

| 2013 | 23.7 | 39.6 | 0.6 | 54.7 | 15.1 | 58.7 | 8.0 | 29.3 |

| 2014 | 13.0 | 45.4 | 2.1 | 264.0 | 7.6 | 49.9 | 3.3 | 58.7 |

| 2015 | 16.6 | 27.8 | 1.0 | 51.7 | 10.6 | 39.8 | 5.0 | 50.1 |

| 2016 | 17.7 | 7.1 | 3.7 | 268.7 | 10.5 | 0.9 | 3.6 | 28.5 |

| 2017 | 13.5 | 23.6 | 2.9 | 21.4 | 7.9 | 24.8 | 2.8 | 22.5 |

| 2018 | 13.8 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 79.0 | 10.2 | 29.5 | 3.0 | 9.0 |

| Year | Infant Mortality | AARR (%) | Under-Five Mortality | AARR (%) | Neonatal Mortality | AARR (%) | Maternal Mortality | AARR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 99.5 | 163.4 | 53.2 | 1136 | ||||

| 2003 | 96.4 | 3.1 | 157.6 | 3.6 | 52.4 | 1.5 | 1100 | 3.2 |

| 2004 | 93.0 | 3.5 | 151.5 | 3.9 | 51.7 | 1.3 | 1008 | 8.4 |

| 2005 | 89.6 | 3.7 | 145.2 | 4.2 | 50.9 | 1.6 | 977 | 3.1 |

| 2006 | 86.2 | 3.8 | 138.9 | 4.3 | 50.0 | 1.8 | 875 | 10.4 |

| 2007 | 82.7 | 4.1 | 132.6 | 4.5 | 49.0 | 2.0 | 845 | 3.4 |

| 2008 | 79.2 | 4.2 | 126.3 | 4.8 | 47.8 | 2.5 | 841 | 0.5 |

| 2009 | 75.8 | 4.3 | 120.1 | 4.9 | 46.5 | 2.7 | 804 | 4.4 |

| 2010 | 72.6 | 4.2 | 114.4 | 4.8 | 45.1 | 3.0 | 795 | 1.1 |

| 2011 | 69.6 | 4.1 | 109.0 | 4.7 | 43.8 | 2.9 | 767 | 3.5 |

| 2012 | 66.7 | 4.2 | 103.9 | 4.7 | 42.5 | 3.0 | 758 | 1.2 |

| 2013 | 64.2 | 3.8 | 99.4 | 4.3 | 41.4 | 2.6 | 742 | 2.1 |

| 2014 | 61.9 | 3.6 | 95.5 | 3.9 | 40.2 | 2.9 | 733 | 1.2 |

| 2015 | 59.9 | 3.2 | 91.8 | 3.9 | 39.2 | 2.5 | 713 | 2.7 |

| 2016 | 58.0 | 3.2 | 88.6 | 3.5 | 38.4 | 2.0 | 673 | 5.6 |

| 2017 | 56.3 | 2.9 | 85.5 | 3.5 | 37.5 | 2.3 | 705 | 4.8 |

| 2018 | 54.6 | 3.0 | 82.4 | 3.6 | 36.7 | 2.1 | 648 | 8.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Casimiro, A.; Branco, J.; Maulide Cane, R.; Andrade, M.J.; Varandas, L.; Craveiro, I. Official Development Assistance and Private Voluntary Support for Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Health in Guinea-Bissau: Assessing Trends and Effectiveness. Children 2025, 12, 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060717

Casimiro A, Branco J, Maulide Cane R, Andrade MJ, Varandas L, Craveiro I. Official Development Assistance and Private Voluntary Support for Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Health in Guinea-Bissau: Assessing Trends and Effectiveness. Children. 2025; 12(6):717. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060717

Chicago/Turabian StyleCasimiro, Anaxore, Joana Branco, Réka Maulide Cane, Michel Jareski Andrade, Luís Varandas, and Isabel Craveiro. 2025. "Official Development Assistance and Private Voluntary Support for Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Health in Guinea-Bissau: Assessing Trends and Effectiveness" Children 12, no. 6: 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060717

APA StyleCasimiro, A., Branco, J., Maulide Cane, R., Andrade, M. J., Varandas, L., & Craveiro, I. (2025). Official Development Assistance and Private Voluntary Support for Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Health in Guinea-Bissau: Assessing Trends and Effectiveness. Children, 12(6), 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060717