Identifying Risk Factors for Dental Neglect in Children Who Failed to Complete Their Dental Surgery Appointments in Northeast Ohio: A Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

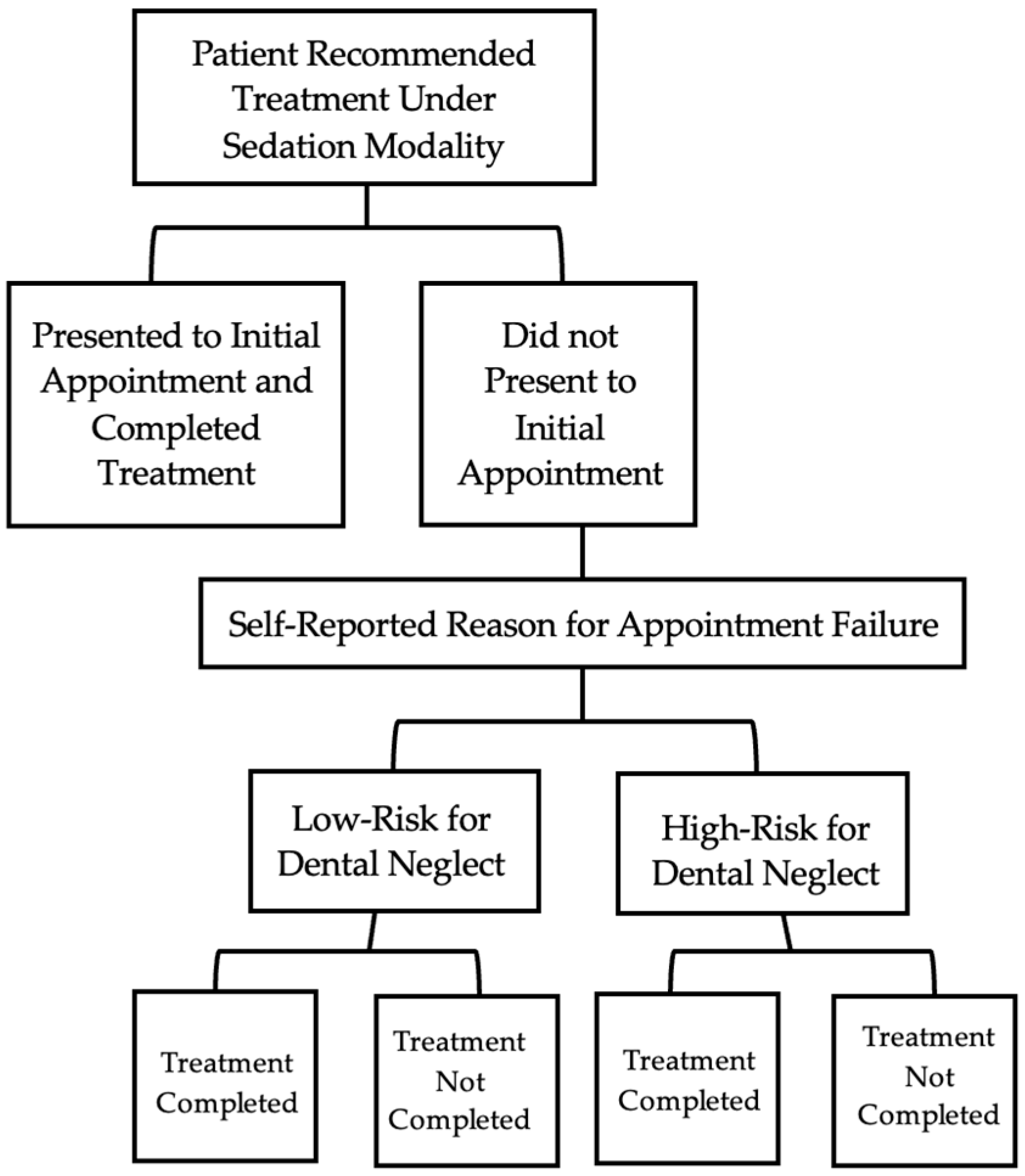

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. IV

3.2. General Anesthesia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- In both IV and GA settings, patients whose appointments were not completed for reasons deemed as high risk for dental neglect were more likely to have uncompleted treatment.

- In the GA setting, the top three high-risk factors for not completing treatment were as follows: (1) failure to commit to schedule the appointment; (2) required medical appointment not completed; (3) no-show on the day of surgery.

- In the IV setting, the top two high-risk factors for not completed treatment were: (1) no-show on the day of surgery; (2) failure to commit to schedule the appointment.

- Because of the findings from this retrospective review, the authors recommend that a future study prospectively evaluating a clinical protocol to report dental neglect cases based on identified high-risk factors is needed.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Katner, D.; Brown, C.; Fournier, S. Considerations in identifying pediatric dental neglect and the legal obligation to report. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2016, 147, 812–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, S.K.; Maguire, S.A.; Chadwick, B.L.; Hunter, M.L.; Harris, J.C.; Tempest, V.; Mann, M.K.; Kemp, A.M. Characteristics of child dental neglect: A systematic review. J. Dent. 2014, 42, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Definition of Dental Neglect. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry; American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry: Chicago, IL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Loochtan, R.M.; Bross, D.C.; Domoto, P.K. Dental neglect in children: Definition, legal aspects, and challenges. Pediatr. Dent. 1986, 8, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Acharya, S.; Tandon, S. The effect of early childhood caries on the quality of life of children and their parents. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2011, 2, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, W.; Tan, S.; Schwartz, S. The effect of severe caries on the quality of life in young children. Pediatr. Dent. 1999, 21, 325–326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Douglass, A.B.; Douglass, J.M. Common dental emergencies. Am. Fam. Physician 2003, 67, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Crescente, G.; Soto de Facchin, C.M.; Acevedo Rodriguez, A.M. Medical-dental considerations in the care of children with facial cellulitis of odontogenic origin. A disease of interest for pediatricians and pediatric dentists. Arch. Argent. Pediatr. 2018, 116, e548–e553. [Google Scholar]

- Pawils, S.; Lindeman, T.; Lemke, R. Dental Neglect and Its Perception in the Dental Practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.C.; Elcock, C.; Sidebotham, P.D.; Welbury, R.R. Safeguarding children in dentistry: 1. Child protection training, experience and practice of dental professionals with an interest in paediatric dentistry. Br. Dent. J. 2009, 206, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgette, J.M.; Safdari-Sadaloo, S.M.; Van Nostrand, E. Child dental neglect laws: Specifications and repercussions for dentists in 51 jurisdictions. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2020, 151, 98–107.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, B.L. Disparities in oral health and access to care: Findings of national surveys. Ambul. Pediatr. 2002, 2 (Suppl. S2), 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzzolese, E.; Lepore, M.M.; Montagna, F.; Marcario, V.; De Rosa, S.; Solarino, B.; Di Vella, G. Child abuse and dental neglect: The dental team’s role in identification and prevention. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2009, 7, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, S.E.; Binkley, C.J.; Neace, W.P.; Gale, B.S. Barriers to care-seeking for children’s oral health among low-income caregivers. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 1345–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Doh, R.M. Dental treatment under general anesthesia for patients with severe disabilities. J. Dent. Anesth. Pain Med. 2021, 21, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mofidi, M.; Rozier, R.G.; King, R.S. Problems with access to dental care for Medicaid-insured children: What caregivers think. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayan, M. No Shows: Effectiveness of Termination Policy and Review of Best Practices. Master’s Thesis, Wright State University, Dayton, OH, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Toema, S.; Ogwo, C.; Patel, N.; Fritz, C.; Catalano, A.; Saclayan, A.; Mekled, S. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on parents seeking dental care for their children. Open J. Pediatr. Child Health 2023, 8, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

| Low-Risk Factors for Dental Neglect | |

| COVID-19 Cancelation | Patient’s appointment was canceled by the clinic due to COVID-19 restrictions |

| Family Emergency | Parent or guardian reported an urgent family matter |

| Lack of Insurance Coverage | Patient did not have active insurance at time of appointment |

| Patient Illness | Patient had an illness that warranted delay of appointment |

| Personal Conflict | Patient’s parent’s or guardian’s morals or ideology did not align with suggested treatment after further consideration |

| Transportation Issues | Patient was unable to secure transportation for appointment |

| Treatment in Different Setting | Patient completed, or is to complete, treatment in other treatment modality or facility |

| Other | Reason does not fit in aforementioned categories |

| High-Risk Factors for Dental Neglect | |

| Canceled Without Reason < 24 h | Guardian canceled previously confirmed appointment < 24 h before appointment without reason |

| Failure to Commit | Patients whose appointment was not scheduled after guardian agreed to suggested treatment |

| No-Show on the Day of Surgery | Patient did not arrive for appointment after appointment was confirmed |

| NPO Violation | Patient broke fasting guidelines given before surgery |

| Required Medical Appointment Not Completed | Patient required clearance visit to specialty physician or primary care physician and did not attend |

| Start Time | Patient failed to show at an appropriate time for procedure to take place |

| Unable to Confirm | Schedulers were unable to contact family to confirm appointment |

| Low-Risk Factors for Dental Neglect (N = 62) (%) | ||

| Reasons for Missing Appointments | Treatment Completed | Treatment Not Completed |

| COVID-19 Cancelation | n = 7 (11.29) | excluded |

| Family Emergency | n = 0 | n = 2 (3.23) |

| Lack of Insurance Coverage | n = 3 (4.84) | n = 5 (8.06) |

| Patient Illness | n = 16 (25.81) | n = 3 (4.84) |

| Personal Conflict | n = 5 (8.06) | n = 6 (9.68) |

| Transportation Issues | n = 3 (4.84) | n = 1 (1.61) |

| Treatment in Different Setting | n = 8 (12.90) | n = 1 (1.61) |

| Other | n = 0 | n = 2 (3.23) |

| Total | n = 42 (67.74) | n = 20 (32.26) |

| High-Risk Factors for Dental Neglect (N = 97) n (%) | ||

| Reasons for Missing Appointments | Treatment Completed | Treatment Not Completed |

| Canceled Without Reason <24 h | n = 0 | n = 0 |

| Failure to Commit | n = 2 (2.06) | n = 21 (21.65) |

| No-Show Day of Surgery | n = 20 (20.62) | n = 23 (23.71) |

| NPO Violation | n = 8 (8.25) | n = 3 (3.09) |

| Required Medical Appointment Not Completed | n = 4 (4.12) | n = 5 (5.15) |

| Start Time | n = 4 (4.12) | n = 2 (2.06) |

| Unable to Confirm | n = 0 | n = 5 (5.15) |

| Total | n = 38 (39.18) | n = 59 (60.82) |

| Low-Risk Factors for Dental Neglect (N = 157) n (%) | ||

| Reasons for Missing Appointments | Treatment Completed | Treatment Not Completed |

| COVID-19 Cancelation | n = 1 (0.64) | excluded |

| Family Emergency | n = 1 (0.64) | n = 0 |

| Lack of Insurance Coverage | n = 20 (12.74) | n = 15 (9.55) |

| Patient Illness | n = 65 (41.40) | n = 12 (7.64) |

| Personal Conflict | n = 15 (9.55) | n = 10 (6.37) |

| Transportation Issues | n = 3 (1.91) | n = 3 (1.91) |

| Treatment in Different Setting | n = 0 | n = 0 |

| Other | n = 2 (1.27) | n = 10 (6.37) |

| Total | n = 107 (68.15) | n = 50 (31.85) |

| High-Risk Factors for Dental Neglect (N= 264) n (%) | ||

| Reasons for Missing Appointments | Treatment Completed | Treatment Not Completed |

| Canceled Without Reason <24 h | n = 3 (1.14) | n = 10 (3.79) |

| Failure to Commit | n = 7 (2.65) | n = 87 (32.95) |

| No-Show Day of Surgery | n = 26 (9.85) | n = 16 (6.06) |

| NPO Violation | n = 7 (2.65) | n = 3 (1.14) |

| Required Medical Appointment Not Completed | n = 34 (12.88) | n = 28 (10.61) |

| Start Time | n = 7 (2.65) | n = 0 |

| Unable to Confirm | n = 23 (8.71) | n = 13 (4.92) |

| Total | n = 107 (40.53) | n = 157 (59.47) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

An, Y.; Ferretti, M.; Jones, L.; Welsh, E.; McCray, J.; Kim, S.; Thompson, M.; Ferretti, G. Identifying Risk Factors for Dental Neglect in Children Who Failed to Complete Their Dental Surgery Appointments in Northeast Ohio: A Retrospective Study. Children 2025, 12, 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060670

An Y, Ferretti M, Jones L, Welsh E, McCray J, Kim S, Thompson M, Ferretti G. Identifying Risk Factors for Dental Neglect in Children Who Failed to Complete Their Dental Surgery Appointments in Northeast Ohio: A Retrospective Study. Children. 2025; 12(6):670. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060670

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Ying, Margaret Ferretti, Lindsey Jones, Eilish Welsh, Justin McCray, Seungchan Kim, Maya Thompson, and Gerald Ferretti. 2025. "Identifying Risk Factors for Dental Neglect in Children Who Failed to Complete Their Dental Surgery Appointments in Northeast Ohio: A Retrospective Study" Children 12, no. 6: 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060670

APA StyleAn, Y., Ferretti, M., Jones, L., Welsh, E., McCray, J., Kim, S., Thompson, M., & Ferretti, G. (2025). Identifying Risk Factors for Dental Neglect in Children Who Failed to Complete Their Dental Surgery Appointments in Northeast Ohio: A Retrospective Study. Children, 12(6), 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060670