Influence of Screen Time on Physical Activity and Lifestyle Factors in German School Children: Interim Results from the Hand-on-Heart-Study (“Hand aufs Herz”)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Influence of Screen Time on Sport Outcomes

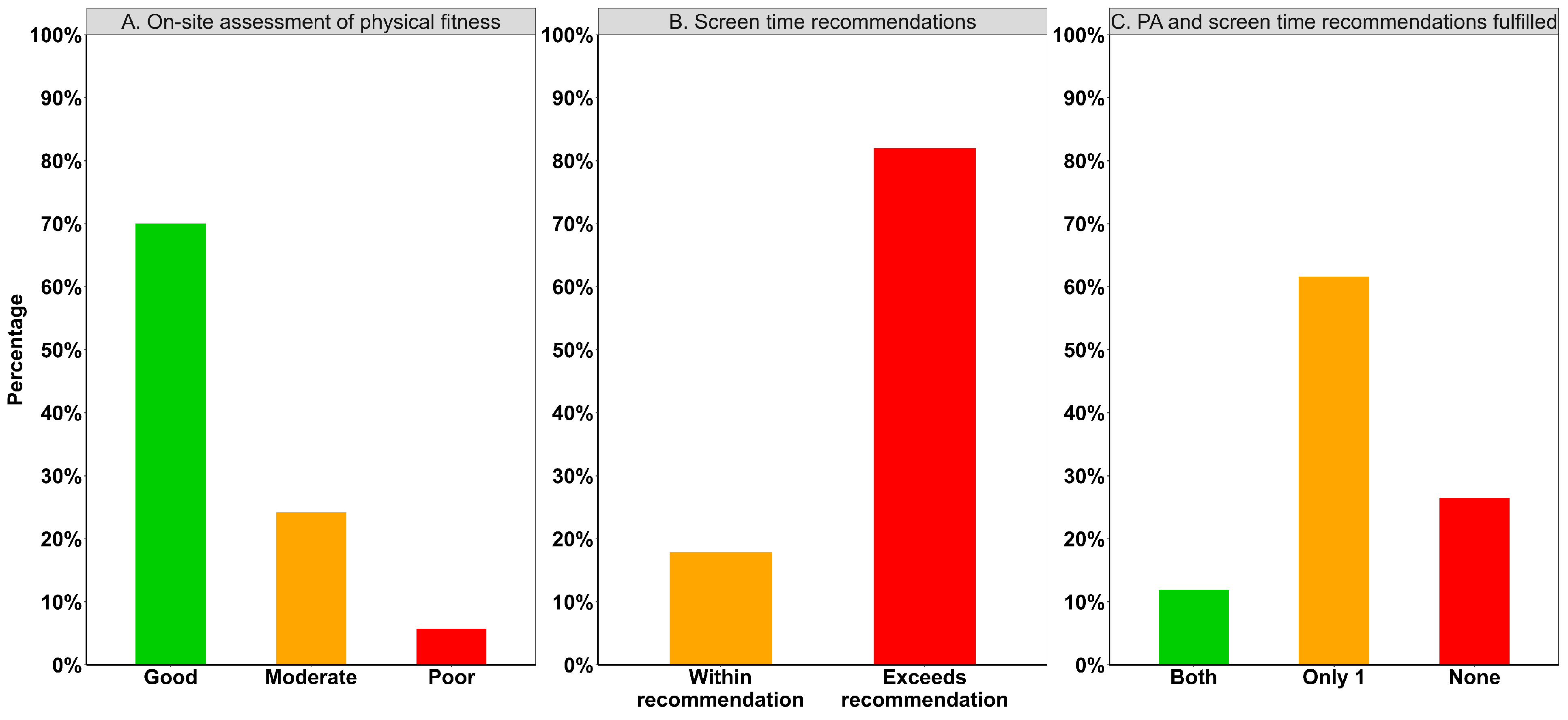

3.2. Adherence on Screen Time and Physical Activity Recommendations

3.3. Lifestyle Indicators and Adherence to Screen Time and Physical Activity Recommendations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| ORs | Odds ratio |

| PA | Physical activity |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| WHO | World health organization |

References

- Luengo-Fernandez, R.; Walli-Attaei, M.; Gray, A.; Torbica, A.; Maggioni, A.P.; Huculeci, R.; Bairami, F.; Aboyans, V.; Timmis, A.D.; Vardas, P.; et al. Economic burden of cardiovascular diseases in the European Union: A population-based cost study. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 4752–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candelino, M.; Tagi, V.M.; Chiarelli, F. Cardiovascular risk in children: A burden for future generations. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents. Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents: Summary Report. Pediatrics 2011, 128, S213–S256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Woo, J.G.; Sinaiko, A.R.; Daniels, S.R.; Ikonen, J.; Juonala, M.; Kartiosuo, N.; Lehtimäki, T.; Magnussen, C.G.; Viikari, J.S.; et al. Childhood Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Adult Cardiovascular Events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1877–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Global Cardiovascular Risk Consortium. The Global Cardiovascular Risk Consortium. Global Effect of Modifiable Risk Factors on Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busnatu, S.S.; Serbanoiu, L.I.; Lacraru, A.E.; Andrei, C.L.; Jercalau, C.E.; Stoian, M.; Stoian, A. Effects of Exercise in Improving Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Overweight Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, A.S.; Dooley, E.E.; Master, H.; Spartano, N.L.; Brittain, E.L.; Pettee Gabriel, K. Physical Activity Over the Lifecourse and Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 1725–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhelst, J.; Le Cunuder, A.; Léger, L.; Duclos, M.; Mercier, D.; Carré, F. Sport participation, weight status, and physical fitness in French adolescents. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2024, 183, 5213–5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, P.A.; Blaha, M.J.; Keteyian, S.J.; Brawner, C.A.; Al Rifai, M.; Dardari, Z.A.; Ehrman, J.K.; Al-Mallah, M.H. Fitness, Fatness, and Mortality: The FIT (Henry Ford Exercise Testing) Project. Am. J. Med. 2016, 129, 960–965.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, M.; Niermann, C.; Jekauc, D.; Woll, A. Long-term health benefits of physical activity—A systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demetriou, Y.; Beck, F.; Sturm, D.; Abu-Omar, K.; Forberger, S.; Hebestreit, A.; Hohmann, A.; Hülse, H.; Kläber, M.; Kobel, S.; et al. Germany’s 2022 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Adolescents. Ger. J. Exerc. Sport Res. 2024, 54, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddock, A.; Ward, N.; Yu, R.; O’Dea, N. Positive Effects of Digital Technology Use by Adolescents: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassiakos, Y.R.; Radesky, J.; Christakis, D.; Moreno, M.A.; Cross, C. Children and Adolescents and Digital Media. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20162593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feierabend, S.; Rathgeb, T.; Kheredmand, H.; Glöckler, S. KIM 2022 Kindheit, Internet, Medien Basisuntersuchung zum Medienumgang 6- bis 13-Jähriger in Deutschland. Medienpädagogischer Forschungsverbund Südwest (mpfs) 2023. Available online: https://mpfs.de/app/uploads/2024/11/KIM-Studie2022_website_final.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Teens, Screens and Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/25-09-2024-teens--screens-and-mental-health (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Feierabend, S.; Rathgeb, T.; Gerigk, Y.; Glöckler, S. JIM 2024 Jugend, Information, Medien Basisuntersuchung zum Medienumgang 12- bis 19-Jähriger in Deutschland (Youth, information, Basic Study on Media Consumption by 12 to 19-Year-Olds in Germany). Medienpädagogischer Forschungsverbund Südwest (mpfs) 2024. Available online: https://mpfs.de/app/uploads/2024/11/JIM_2024_PDF_barrierearm.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Rohleder, B. Kinder & Jugendstudie (Children & Youth Study); Bitcom Research: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin e.V. DGKJ. SK2-Leitlinie: Leitlinie zur Prävention Dysregulierten Bildschirmmediengebrauchs in der Kindheit und Jugend. 1. 2022. Available online: https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/027-075 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Hansen, J.; Hanewinkel, R.; Galimov, A. Physical activity, screen time, and sleep: Do German children and adolescents meet the movement guidelines? Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 1985–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pediatric Cardiology Department of the University Hospital Munich. Available online: https://www.lmu-klinikum.de/kinderkardiologie (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Definition Adipositas im Kindes & Jugendalter—Adipositas Gesellschaft (Definition of Childhood and Adolescent Obesity—Obesity Society). Available online: https://adipositas-gesellschaft.de/ueber-adipositas/adipositas-im-kindes-jugendalter/ (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Mall, M.P.; Wander, J.; Lentz, A.; Jakob, A.; Oberhoffer, F.S.; Mandilaras, G.; Haas, N.A.; Dold, S.K. Step by Step: Evaluation of Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Healthy Children, Young Adults, and Patients with Congenital Heart Disease Using a Simple Standardized Stair Climbing Test. Children 2024, 11, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Poster Bewegung, Mediennutzung und Schlaf (Motion, Media Use and Sleep)—BIÖG Shop. Available online: https://shop.bzga.de/poster-bewegung-mediennutzung-und-schlaf/ (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Qi, J.; Yan, Y.; Yin, H. Screen time among school-aged children of aged 6–14: A systematic review. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2023, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, T.N.; Banda, J.A.; Hale, L.; Lu, A.S.; Fleming-Milici, F.; Calvert, S.L.; Wartella, E. Screen Media Exposure and Obesity in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics 2017, 140, S97–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Riesch, S.; Tien, J.; Lipman, T.; Pinto-Martin, J.; O’Sullivan, A. Screen Media Overuse and Associated Physical, Cognitive, and Emotional/Behavioral Outcomes in Children and Adolescents: An Integrative Review. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2022, 36, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woll, A.; Burchartz, A.; Niessner, C.; Worth, A. Die MoMo-Längsschnittstudie: Entwicklung motorischer Leistungsfähigkeit und Körperlich-Sportlicher Aktivität und ihre Wirkung auf die Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland; Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT), Institut für Sport und Sportwissenschaft (IfSS): Karlsruhe, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://www.ifss.kit.edu/MoMo/fuer_Medien_und_Experten_Ergebnisse.php (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Memaran, N.; Schwalba, M.; Borchert-Mörlins, B.; Von Der Born, J.; Markefke, S.; Bauer, E.; von Wick, A.; Epping, J.; von Maltzahn, N.; Heyn-Schmidt, I.; et al. Gesundheit und Fitness von deutschen Schulkindern: Übergewicht und Adipositas sind signifikant mit kardiovaskulären Risikofaktoren assoziiert. Monatsschr. Kinderheilkd. 2020, 168, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, A.P.; Dengel, D.R.; Lubans, D.R. Supporting Public Health Priorities: Recommendations for Physical Education and Physical Activity Promotion in Schools. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 57, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, S.; Buoncristiano, M.; Gelius, P.; Abu-Omar, K.; Pattison, M.; Hyska, J.; Duleva, V.; Musić Milanović, S.; Zamrazilová, H.; Hejgaard, T.; et al. Physical Activity, Screen Time, and Sleep Duration of Children Aged 6–9 Years in 25 Countries: An Analysis within the WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI) 2015–2017. Obes. Facts. 2021, 14, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Tang, X.; Peng, X.; Hao, G.; Luo, S.; Liang, X. Effect of screen time intervention on obesity among children and adolescent: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Prev. Med. 2022, 157, 107014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Home Page Nicolas May Stiftung. Available online: https://www.nicolas-may-stiftung.de/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

| Characteristics | All Children | Screen Time During Weekday | Screen Time During Weekend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤2 h | >2 h | p-Value | ≤2 h | >2 h | p-Value | ||

| Number of pupils, N | 883 | 324 | 559 | 213 | 670 | ||

| Sex | 0.292 | 0.805 | |||||

| Male | 477 (54.0) | 167 (51.5) | 310 (55.5) | 113 (53.1) | 364 (54.3) | ||

| Female | 406 (46.0) | 157 (48.5) | 249 (44.5) | 100 (46.9) | 306 (45.7) | ||

| Age, years | 13.1 (2.4) | 11.7 (2.2) | 13.9 (2.1) | <0.001 | 11.3 (2.2) | 13.6 (2.1) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (BMI), kg/m2 | 19.4 (3.7) | 18.0 (3.2) | 20.2 (3.7) | <0.001 | 17.6 (3.1) | 20.0 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| School level | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Primary school | 100 (11.3) | 81 (25.0) | 19 (3.4) | 63 (29.6) | 37 (5.5) | ||

| Middle school | 58 (6.6) | 10 (3.1) | 48 (8.6) | 9 (4.2) | 49 (7.3) | ||

| Secondary school | 604 (68.4) | 189 (58.3) | 415 (74.2) | 111 (52.1) | 493 (73.6) | ||

| High school | 121 (13.7) | 44 (13.6) | 77 (13.8) | 30 (14.1) | 91 (13.6) | ||

| Outcome | Screen Time During Weekday | Screen Time During Weekend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Unadjusted | Age-Adjusted | Unadjusted | Age-Adjusted | |

| Sports grade at school | |||||

| 1 | 524 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 2 | 288 | 2.14 (1.57, 2.92) | 1.80 (1.27, 2.54) | 1.93 (1.35, 2.76) | 1.52 (1.03, 2.25) |

| ≥3 | 71 | 3.23 (1.76, 5.95) | 2.82 (1.46, 5.42) | 3.28 (1.53, 7.00) | 2.69 (1.20, 6.01) |

| Sports club membership | |||||

| Yes | 639 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| No | 244 | 2.35 (1.68, 3.29) | 1.75 (1.22, 2.53) | 2.13 (1.44, 3.14) | 1.48 (0.97, 2.25) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wieprecht, J.; Gomes, D.; Morassutti Vitale, F.; Manai, S.K.; Shamas, S.; Müller, M.; Baethmann, M.; Tengler, A.; Riley, R.; Mandilaras, G.; et al. Influence of Screen Time on Physical Activity and Lifestyle Factors in German School Children: Interim Results from the Hand-on-Heart-Study (“Hand aufs Herz”). Children 2025, 12, 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050576

Wieprecht J, Gomes D, Morassutti Vitale F, Manai SK, Shamas S, Müller M, Baethmann M, Tengler A, Riley R, Mandilaras G, et al. Influence of Screen Time on Physical Activity and Lifestyle Factors in German School Children: Interim Results from the Hand-on-Heart-Study (“Hand aufs Herz”). Children. 2025; 12(5):576. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050576

Chicago/Turabian StyleWieprecht, Jennifer, Delphina Gomes, Federico Morassutti Vitale, Simone Katrin Manai, Samar Shamas, Marcel Müller, Maren Baethmann, Anja Tengler, Roxana Riley, Guido Mandilaras, and et al. 2025. "Influence of Screen Time on Physical Activity and Lifestyle Factors in German School Children: Interim Results from the Hand-on-Heart-Study (“Hand aufs Herz”)" Children 12, no. 5: 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050576

APA StyleWieprecht, J., Gomes, D., Morassutti Vitale, F., Manai, S. K., Shamas, S., Müller, M., Baethmann, M., Tengler, A., Riley, R., Mandilaras, G., Haas, N. A., & Schrader, M. (2025). Influence of Screen Time on Physical Activity and Lifestyle Factors in German School Children: Interim Results from the Hand-on-Heart-Study (“Hand aufs Herz”). Children, 12(5), 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050576