Family Factors and the Psychological Well-Being of Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—An Exploratory Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

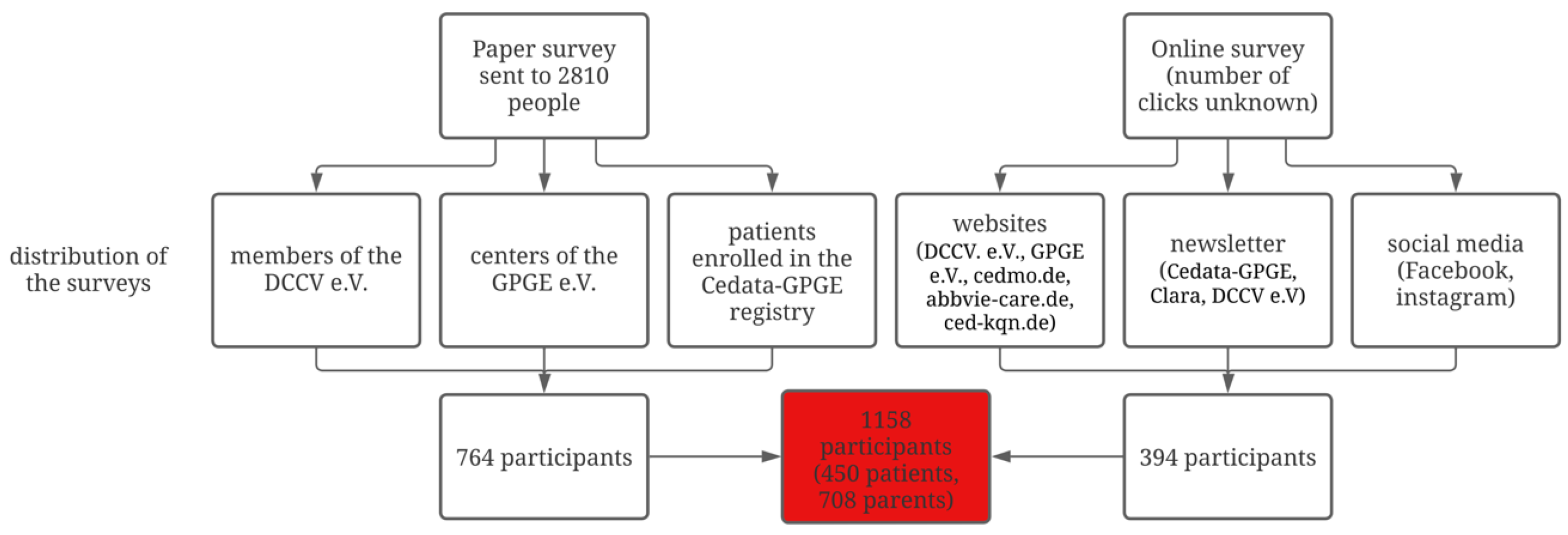

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Patient and Parent Characteristics

2.3.2. Family Structures

2.3.3. Siblings

2.3.4. Psychological Problems of the Patient

2.3.5. Patient Emotions

2.3.6. Patient and Parent Emotional Coping

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient and Parent Characteristics

3.2. Family Structures and Psychological Problems

3.3. Siblings and Psychological Problems

3.4. Family Structures and Emotions

3.5. Siblings and Emotions

3.6. Parent–Child Emotional Coping

4. Discussion

4.1. Family Structures and Psychological Problems/Disease-Related Emotions

4.2. Siblings and Psychological Problems/Disease-Related Emotions

4.3. Emotional Coping Abilities of Parents and Children

4.4. Limitations and Strenghts

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CI | Confidence interval |

| DCCV e.V. | Deutsche Morbus Crohn/Colitis Ulcerosa Vereinigung |

| GPGE e.V | Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Gastroenterologie und Ernährung |

| HRQoL | Health-related quality of life |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| pIBD | Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| yr | Year |

References

- Kuenzig, M.E.; Fung, S.G.; Marderfeld, L.; Mak, J.W.Y.; Kaplan, G.G.; Ng, S.C.; Wilson, D.C.; Cameron, F.; Henderson, P.; Kotze, P.G.; et al. Twenty-First Century Trends in the Global Epidemiology of Pediatric-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Systematic Review. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 1147–1159.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittig, R.; Albers, L.; Koletzko, S.; Saam, J.; von Kries, R. Pediatric Chronic Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a German Statutory Health INSURANCE—Incidence Rates From 2009 to 2012. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 68, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.R.; Rodriguez, J.R. Clinical Presentation of Crohn’s, Ulcerative Colitis, and Indeterminate Colitis: Symptoms, Extraintestinal Manifestations, and Disease Phenotypes. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2017, 26, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B. Stigma, Deviance and Morality in Young Adults’ Accounts of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Sociol. Health. Illn. 2014, 36, 1020–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, S.R.; Graff, L.A.; Wilding, H.; Hewitt, C.; Keefer, L.; Mikocka-Walus, A. Quality of Life in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses—Part I. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.C.; Strachan, J.; Russell, R.K.; Wilson, S.L. Psychosocial Functioning and Health-Related Quality of Life in Paediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2011, 53, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenley, R.N.; Hommel, K.A.; Nebel, J.; Raboin, T.; Li, S.-H.; Simpson, P.; Mackner, L. A Meta-Analytic Review of the Psychosocial Adjustment of Youth with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2010, 35, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väistö, T.; Aronen, E.T.; Simola, P.; Ashorn, M.; Kolho, K.-L. Psychosocial Symptoms and Competence among Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Their Peers. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, A.J.; Rowse, G.; Ryder, A.; Peach, E.J.; Corfe, B.M.; Lobo, A.J. Systematic Review: Psychological Morbidity in Young People with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—Risk Factors and Impacts. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 44, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Tilburg, M.A.L.; Claar, R.L.; Romano, J.M.; Langer, S.L.; Drossman, D.A.; Whitehead, W.E.; Abdullah, B.; Levy, R.L. Psychological Factors May Play an Important Role in Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Symptoms and Disability. J. Pediatr. 2017, 184, 94–100.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhee, M.; Hoffenberg, E.J.; Feranchak, A. Quality-of-Life Factors in Adolescent Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 1998, 4, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cushman, G.; Shih, S.; Reed, B. Parent and Family Functioning in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Children 2020, 7, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindfred, H.; Saalman, R.; Nilsson, S.; Reichenberg, K. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Self-Esteem in Adolescence. Acta Paediatr. 2008, 97, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alleinerziehende—Tabellenband zur Pressekonferenz am 02.08.2018 in Berlin—Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus—2017. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Haushalte-Familien/Publikationen/Downloads-Haushalte/alleinerziehende-tabellenband-5122124179004.html (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Rattay, P.; von der Lippe, E.; Lampert, T. Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Eineltern-, Stief- und Kernfamilien. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2014, 57, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, W.N.; Graef, D.M.; Schuman, S.S.; Janicke, D.M.; Hommel, K.A. Parenting Stress in Pediatric IBD: Relations with Child Psychopathology, Family Functioning, and Disease Severity. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2013, 34, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanberger, L.; Ludvigsson, J.; Nordfeldt, S. Health-Related Quality of Life in Intensively Treated Young Patients with Type 1 Diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2009, 10, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baechle, C.; Stahl-Pehe, A.; Castillo, K.; Selinski, S.; Holl, R.W.; Rosenbauer, J. Association of Family Structure with Type 1 Diabetes Management and Outcomes in Adolescents: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Pediatr. Diabetes 2021, 22, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlarb, P.; Büttner, J.M.; Tittel, S.R.; Mönkemöller, K.; Müller-Godeffroy, E.; Boettcher, C.; Galler, A.; Berger, G.; Brosig, B.; Holl, R.W. Family Structures and Parents’ Occupational Models: Its Impact on Children’s Diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2024, 61, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, G.H. Siblings’ Direct and Indirect Contributions to Child Development. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 13, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Itzchak, E.; Nachshon, N.; Zachor, D.A. Having Siblings Is Associated with Better Social Functioning in Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2019, 47, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buist, K.L.; Deković, M.; Prinzie, P. Sibling Relationship Quality and Psychopathology of Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J. The Only Child in America: Prejudice versus Performance. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1981, 7, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, D.B. Number of Siblings and Intellectual Development: The Resource Dilution Explanation. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downey, D.B.; Cao, R. Number of Siblings and Mental Health Among Adolescents: Evidence From the U.S. and China. J. Fam. Issues 2024, 45, 2822–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcı, E.; Sak, R. The Relationship between Parenting Styles and Fourth Graders’ Levels of Empathy and Aggressiveness. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nap-van der Vlist, M.M.; van der Wal, R.C.; Grosfeld, E.; van de Putte, E.M.; Dalmeijer, G.W.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; van der Ent, C.K.; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.; Swart, J.F.; Bodenmann, G.; et al. Parent-Child Dyadic Coping and Quality of Life in Chronically Diseased Children. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 701540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudino, M.N.; Gamwell, K.L.; Roberts, C.M.; Grunow, J.E.; Jacobs, N.J.; Gillaspy, S.R.; Edwards, C.S.; Mullins, L.L.; Chaney, J.M. Disease Severity and Depressive Symptoms in Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: The Mediating Role of Parent and Youth Illness Uncertainty. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2019, 44, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed-Knight, B.; Lee, J.L.; Greenley, R.N.; Lewis, J.D.; Blount, R.L. Disease Activity Does Not Explain It All: How Internalizing Symptoms and Caregiver Depressive Symptoms Relate to Health-Related Quality of Life Among Youth with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 963–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, T.M.; Valrie, C.R.; Karlson, C.W. Family and Parent Influences on Pediatric Chronic Pain: A Developmental Perspective. Am. Psychol. 2014, 69, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, K.; Schumann, S.; Sander, C.; Däbritz, J.; de Laffolie, J. A Nationwide Survey on Patient Empowerment in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Germany. Children 2023, 10, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, M.; Grootenhuis, M.; Derkx, B.; Last, B. Health-Related Quality of Life and Psychosocial Functioning of Adolescents With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2005, 11, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttmann-Steinmetz, S.; Crowell, J.A. Attachment and Externalizing Disorders: A Developmental Psychopathology Perspective. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2006, 45, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Child/Adolescent Data | Patient Survey | Parent Survey |

|---|---|---|

| Child’s age (yr) | n = 365 | n = 614 |

| Mean (SD) | 14.8 (1.5) | 12.9 (3.3) |

| Gender (%) | n = 381 | n = 615 |

| Female | 50.4 | 48.0 |

| Male | 48.3 | 51.9 |

| Diverse | 1.3 | 0.2 |

| Family structure (%) | n = 377 | n = 573 |

| Two-parent household | 82.0 | 86.2 |

| Single-parent household | 9.5 | 11.2 |

| Other | 8.5 | 2.6 |

| Siblings (%) | n = 381 | n = 570 |

| No siblings | 16.3 | 19.5 |

| Has siblings | 83.7 | 80.5 |

| 1–2 siblings | 74.5 | 71.2 |

| ≥3 siblings | 9.2 | 9.3 |

| Diagnosis (%) | n = 410 | n = 613 |

| Crohn’s disease, | 52.4 | 51.2 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 42.2 | 40.8 |

| IBD unclassified | 5.4 | 8.0 |

| Disease duration (yr) | n = 410 | n = 616 |

| Median | 1–2 | 1–2 |

| Disease phase (%) | n = 403 | n = 611 |

| Remission | 75.7 | 68.4 |

| Flare up | 12.4 | 15.6 |

| Diagnosis | 1.5 | 4.3 |

| I don’t know | 10.4 | 11.8 |

| Disease course of the child (%) | n = 603 | |

| Sustained remission | 54.4 | |

| Recurrent flares | 25.5 | |

| Active disease | 17.4 | |

| Increasing activity | 2.7 | |

| Parent data | ||

| Parental age group (yr) | n = 574 | |

| Median | 41–60 | |

| Educational attainment of the parents (%) | n = 560 | |

| University degree | 25.4 | |

| Apprenticeship or vocational training | 51.8 | |

| Polytechnic degree | 17.9 | |

| None | 5.0 |

| Patient Survey | Parent Survey | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (CI) | p-Value | OR (CI) | p-Value | |

| Two-parent household | 0.47 (0.22–1.07) | 0.060 * | 0.67 (0.34–1.48) | 0.294 |

| Single-parent household | 1.89 (0.76–4.26) | 0.144 | 1.70 (0.74–3.54) | 0.177 |

| Other family structure | 1.53 (0.43–4.24) | 0.457 | 0.66 (0.04–3.38) | 0.690 |

| Has siblings | 0.60 (0.27–1.48) | 0.233 | 0.90 (0.46–1.90) | 0.772 |

| 1–2 siblings | 0.45 (0.22–0.95) | 0.032 * | 0.70 (0.39–1.30) | 0.249 |

| ≥3 siblings | 2.31 (0.81–5.71) | 0.088 * | 1.77 (0.73–3.80) | 0.170 |

| No siblings | 1.67 (0.68–3.75) | 0.233 | 1.11 (0.53–2.16) | 0.772 |

| Sad | Afraid | Insecure | Helpless | Exhaust-ed | Left Alone | Over-Whelmed | Nervous | Shame | Loneli-ness | Loss of Courage | Calm | Fine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-parent household | 0.36 *** | 0.58 | 0.69 | 0.30 ** | 0.63 | 0.37 * | 0.70 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.45 * | 0.68 | 1.11 | 1.26 |

| One-parent household | 2.69 ** | 1.96 * | 1.70 * | 4.09 ** | 1.65 | 2.56 * | 1.38 | 0.95 | 1.61 | 2.76 ** | 1.81 | 0.80 | 0.64 |

| Other family stuctures | 1.48 | 0.99 | 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.76 | 2.90 * | 0.75 | 0.41 | 0.70 | 1.11 | 1.12 | 2.06 | 2.23 |

| Has siblings | 0.66 | 0.45 * | 0.68 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 1.17 | 0.73 | 1.60 | 1.80 | 1.27 | 2.01 | 1.16 | 1.19 |

| 1–2 siblings | 0.77 | 0.43 ** | 0.65 * | 0.61 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.99 | 1.36 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 1.42 | 2.19 * |

| ≥3 siblings | 0.91 | 1.66 | 1.42 | 2.34 | 1.53 | 1.80 | 1.47 | 1.71 | 1.15 | 1.72 | 2.48 | 0.58 | 0.28 ** |

| No siblings | 1.51 | 2.24 * | 1.47 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 0.85 | 1.37 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.78 | 0.50 | 0.86 | 0.84 |

| Parents | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Little to None | Mostly | Always | |||

| OR(CI) | p-Value | OR(CI) | p-Value | OR(CI) | p-Value | |

| Little to none | 7.77 (1.92–27.20) | 0.002 ** | 1.35 (0.47–3.95) | 0.578 | 0.25 (0.06–0.82) | 0.037 * |

| Mostly | 1.38 (0.45–3.97) | 0.551 | 1.89 (1.13–3.21) | 0.017 * | 0.49 (0.28–0.82) | 0.008 ** |

| Always | 0.29 (0.09–0.85) | 0.030 * | 0.51 (0.31–0.85) | 0.010 * | 2.60 (1.56–4.40) | <0.001 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hieronymi, C.; Kaul, K.; de Laffolie, J.; Brosig, B.; on behalf of Cedata-GPGE AG. Family Factors and the Psychological Well-Being of Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—An Exploratory Study. Children 2025, 12, 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050575

Hieronymi C, Kaul K, de Laffolie J, Brosig B, on behalf of Cedata-GPGE AG. Family Factors and the Psychological Well-Being of Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—An Exploratory Study. Children. 2025; 12(5):575. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050575

Chicago/Turabian StyleHieronymi, Chantal, Kalina Kaul, Jan de Laffolie, Burkhard Brosig, and on behalf of Cedata-GPGE AG. 2025. "Family Factors and the Psychological Well-Being of Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—An Exploratory Study" Children 12, no. 5: 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050575

APA StyleHieronymi, C., Kaul, K., de Laffolie, J., Brosig, B., & on behalf of Cedata-GPGE AG. (2025). Family Factors and the Psychological Well-Being of Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—An Exploratory Study. Children, 12(5), 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050575