A National Trauma-Informed Adverse Childhood Experience Screening and Intervention Evaluation Project

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Types of Practices

3.2. Patient Demographics

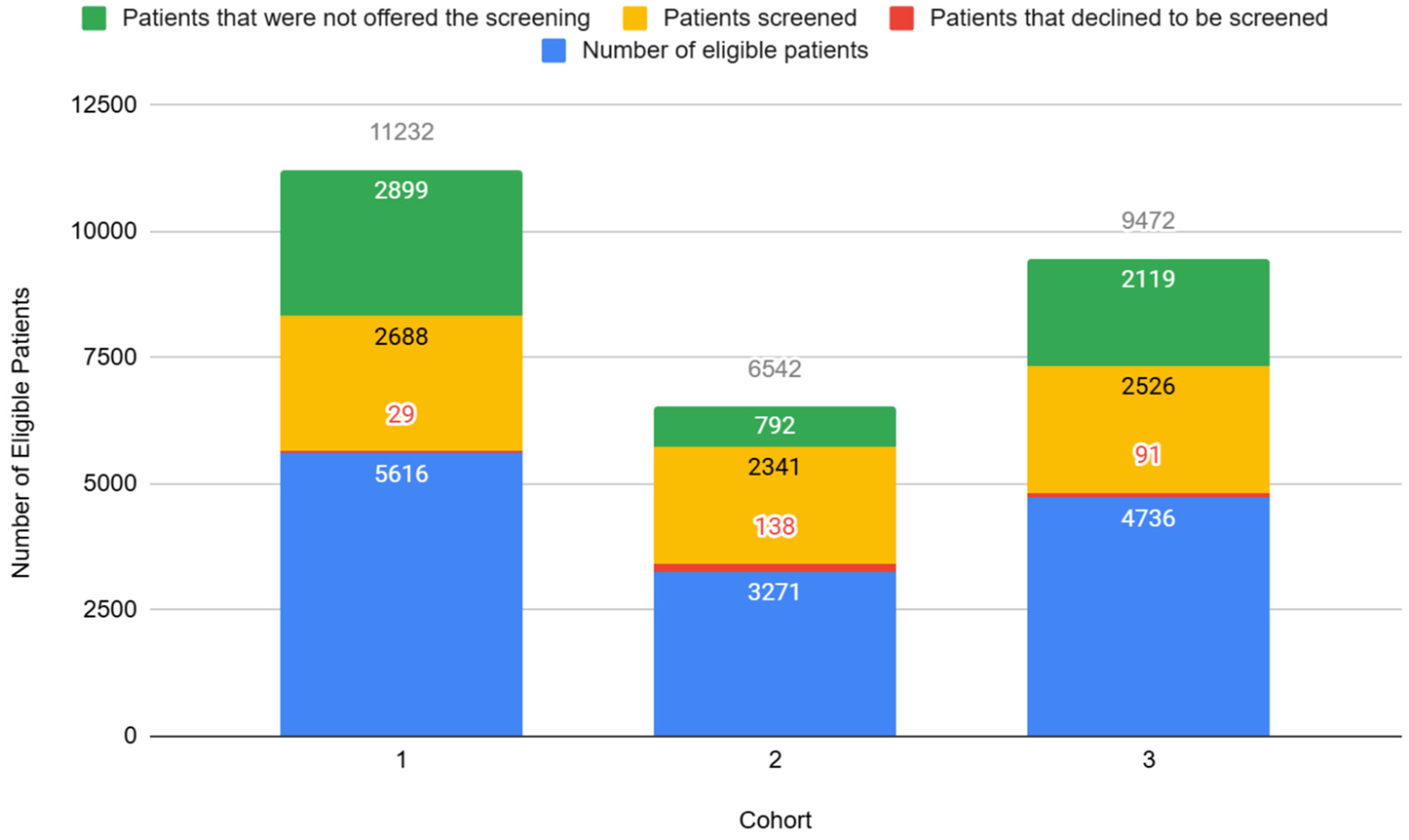

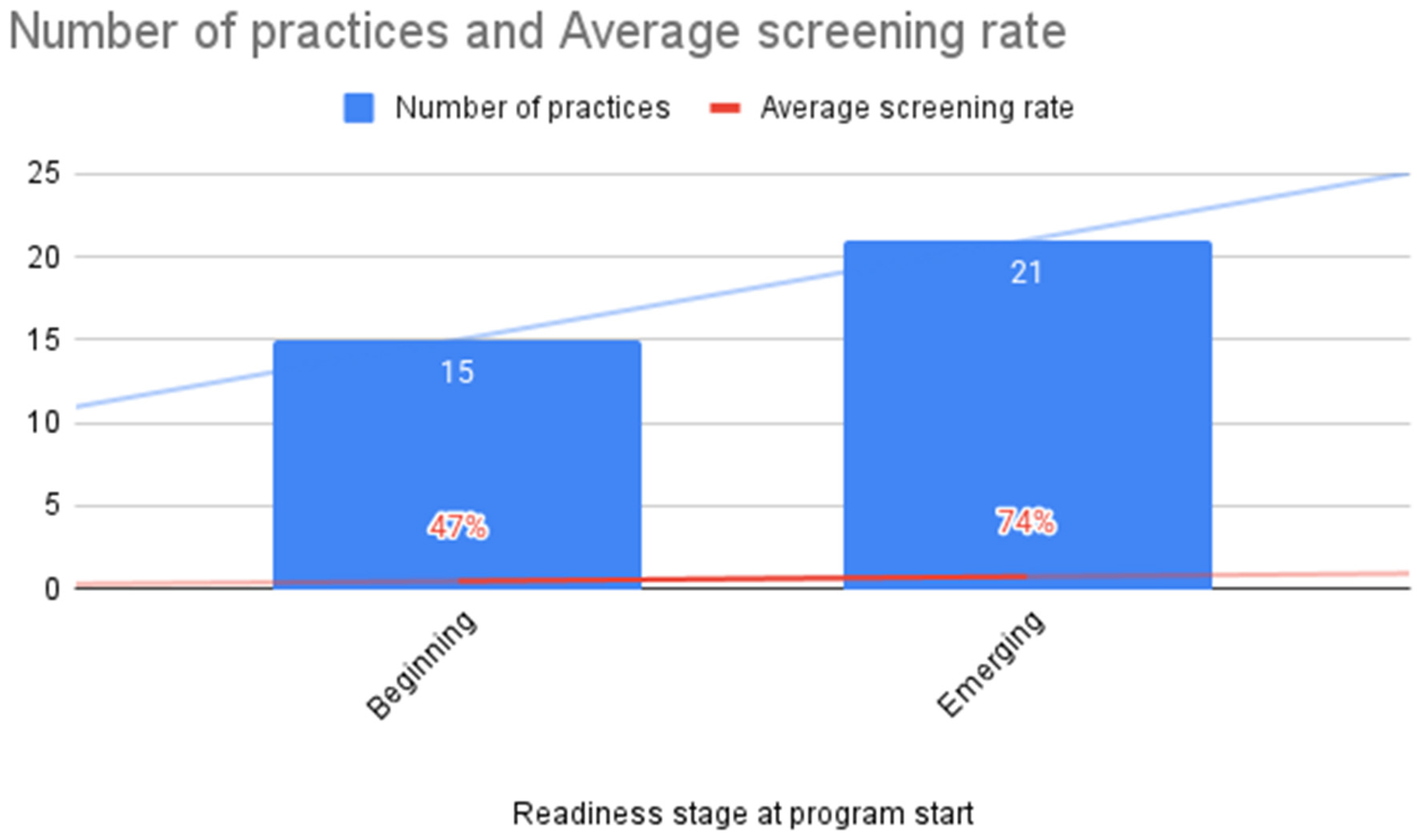

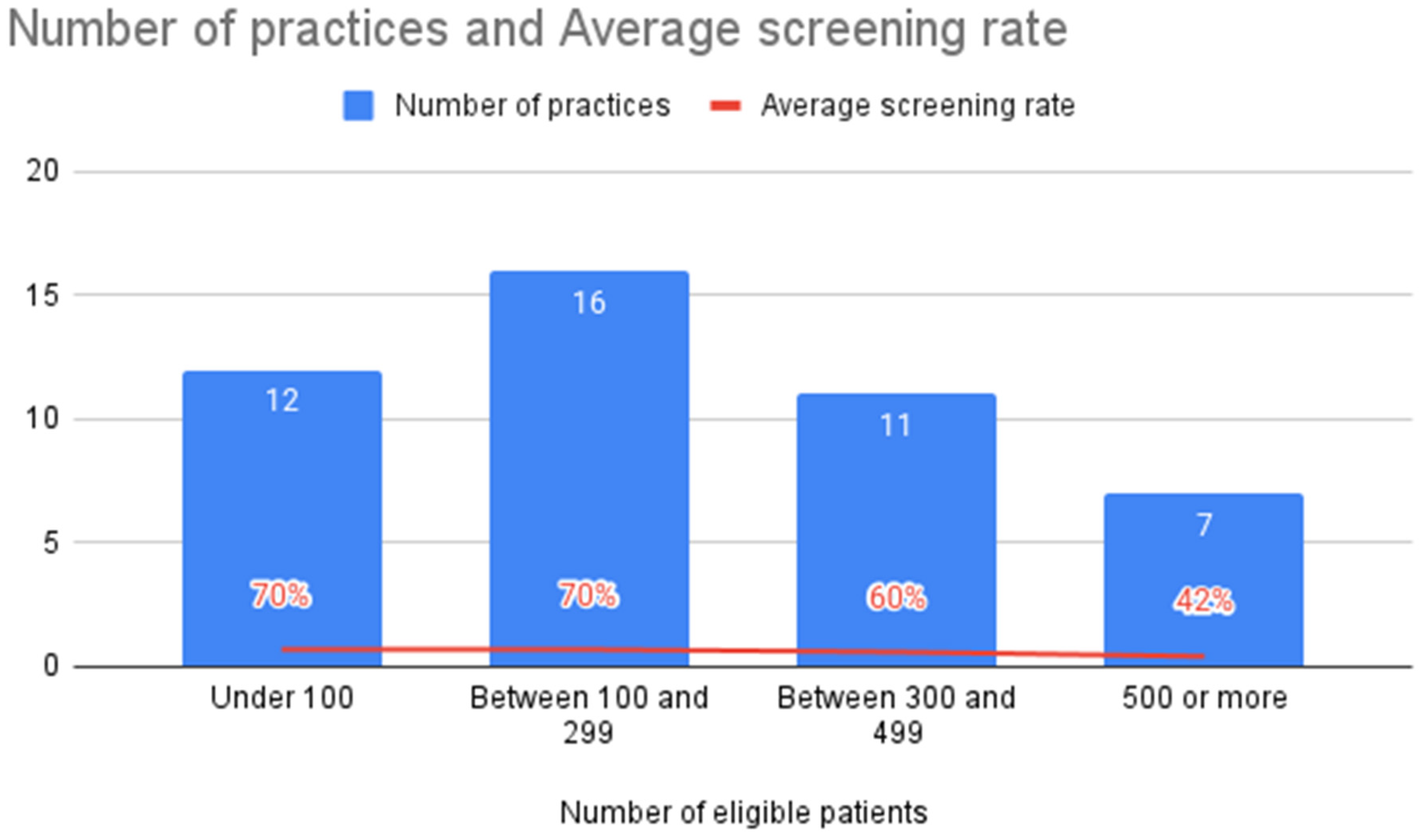

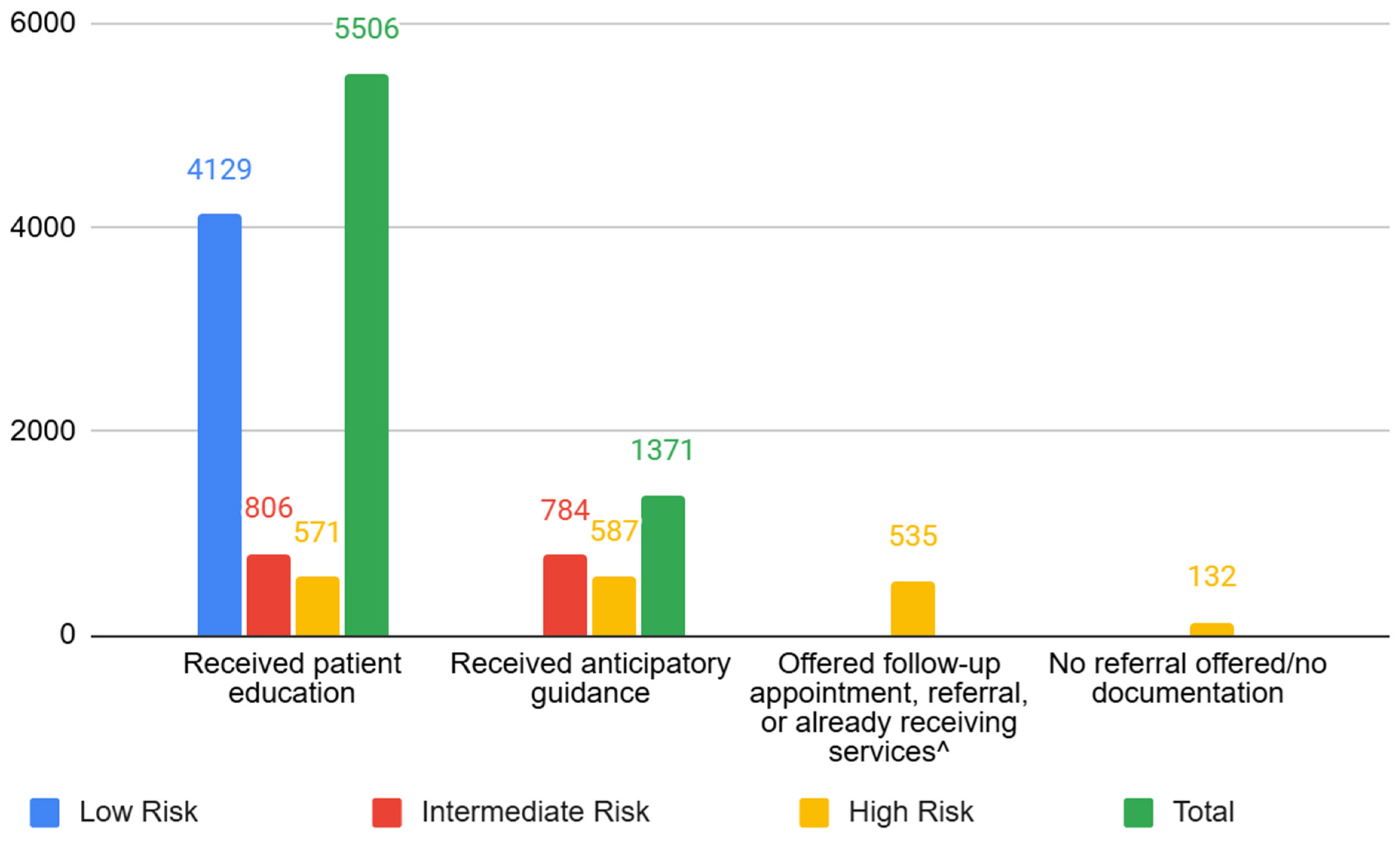

3.3. ACE Screening Implementation

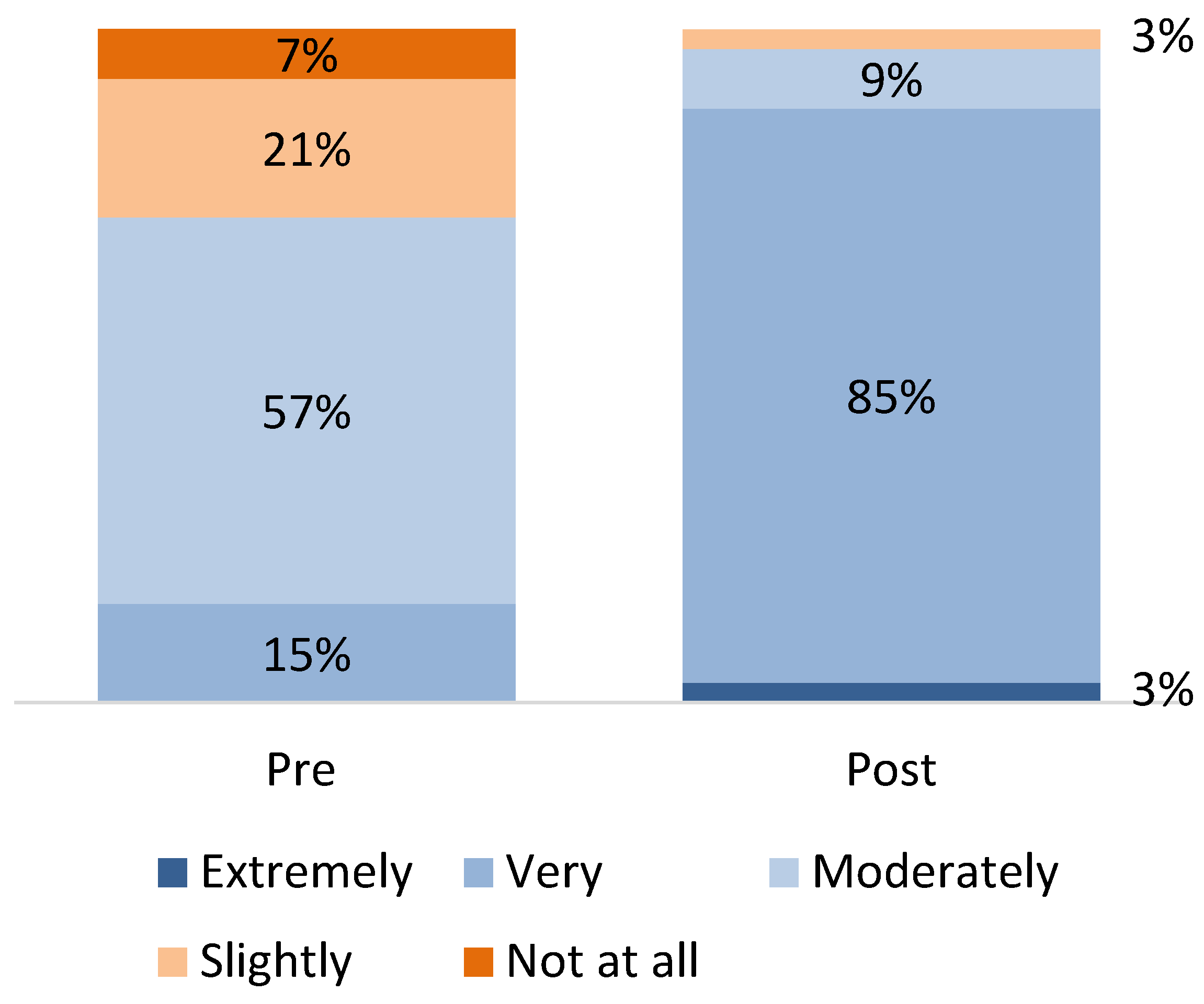

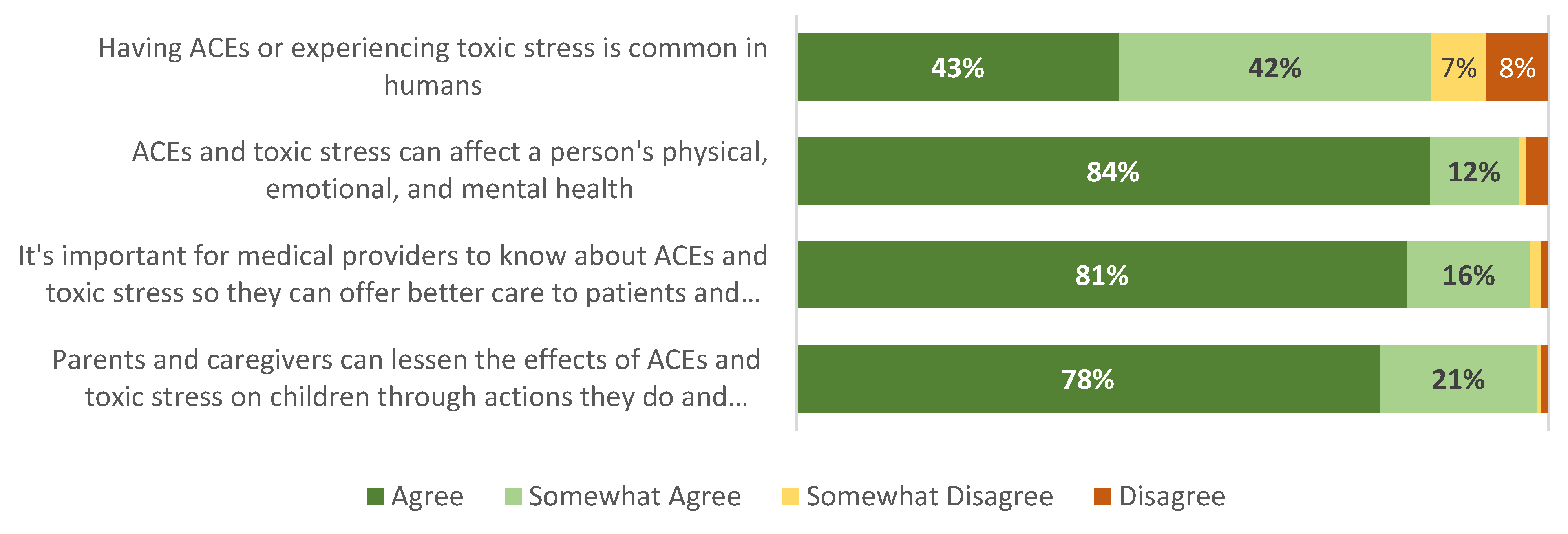

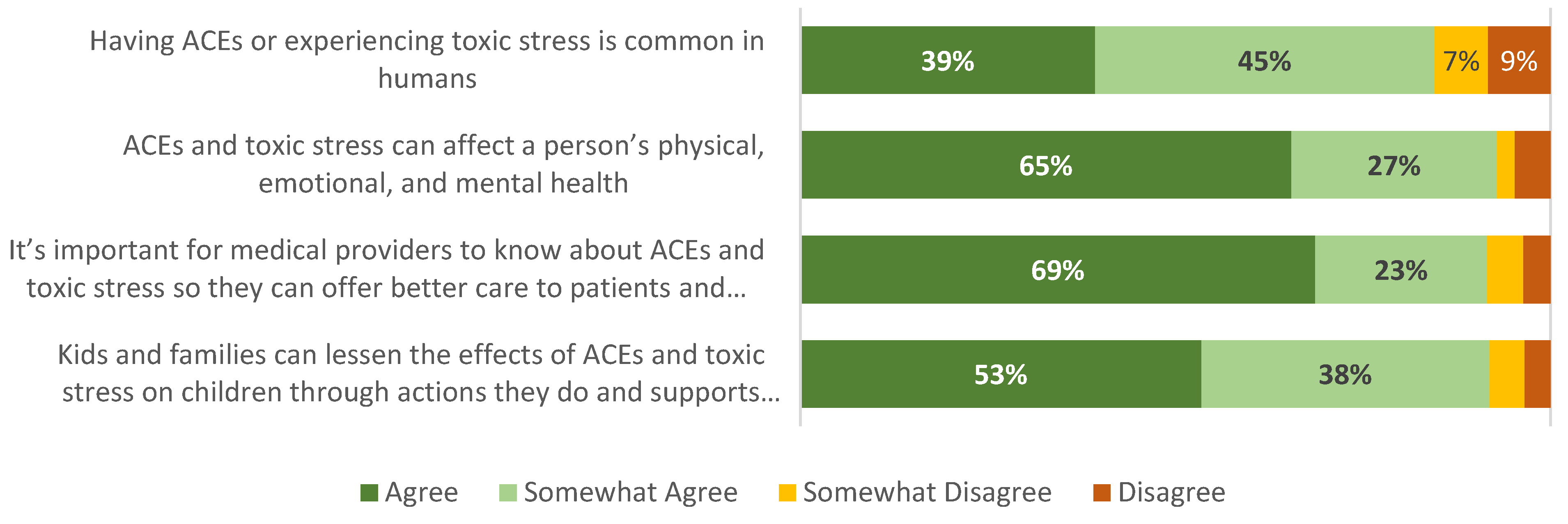

3.4. Provider Knowledge

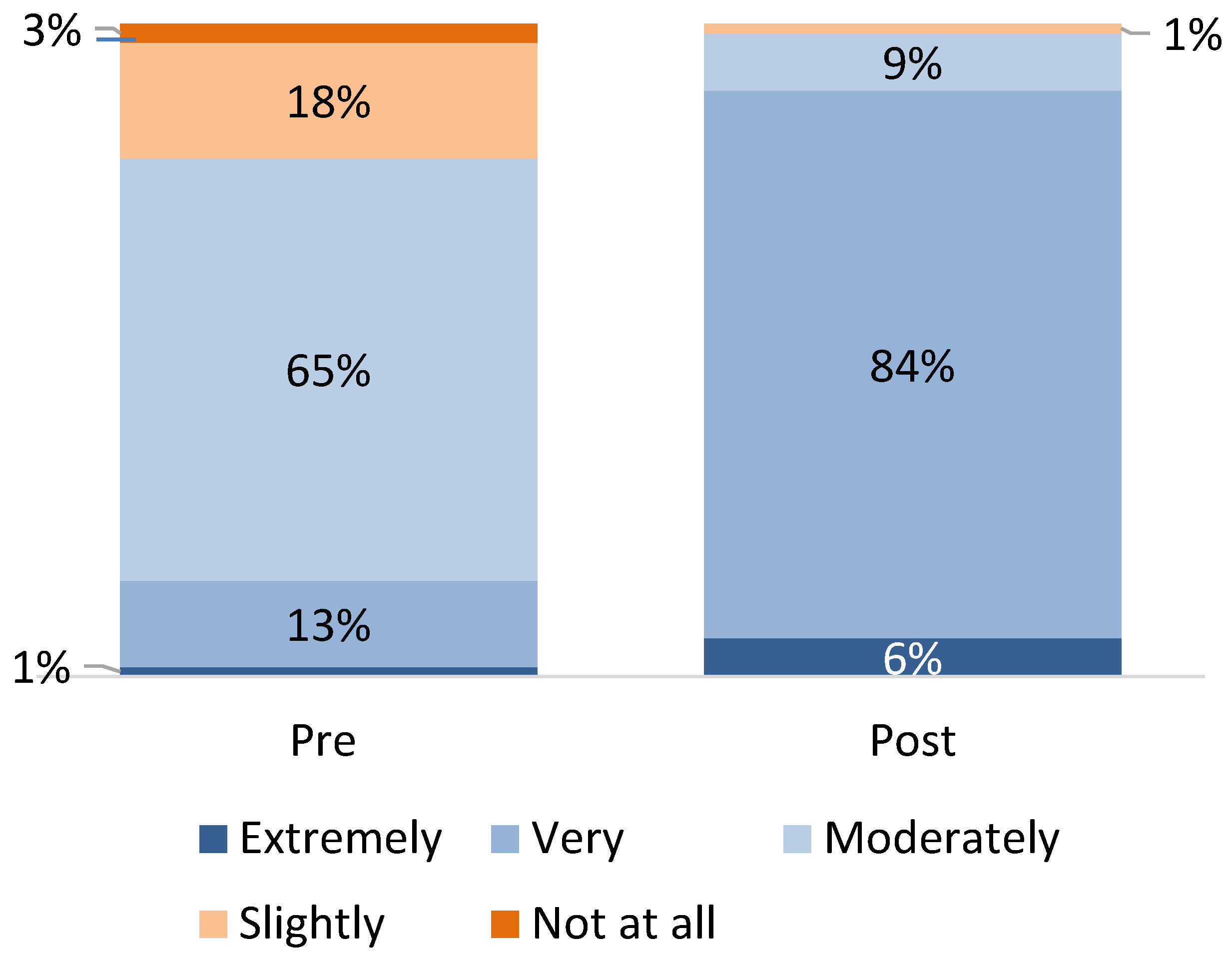

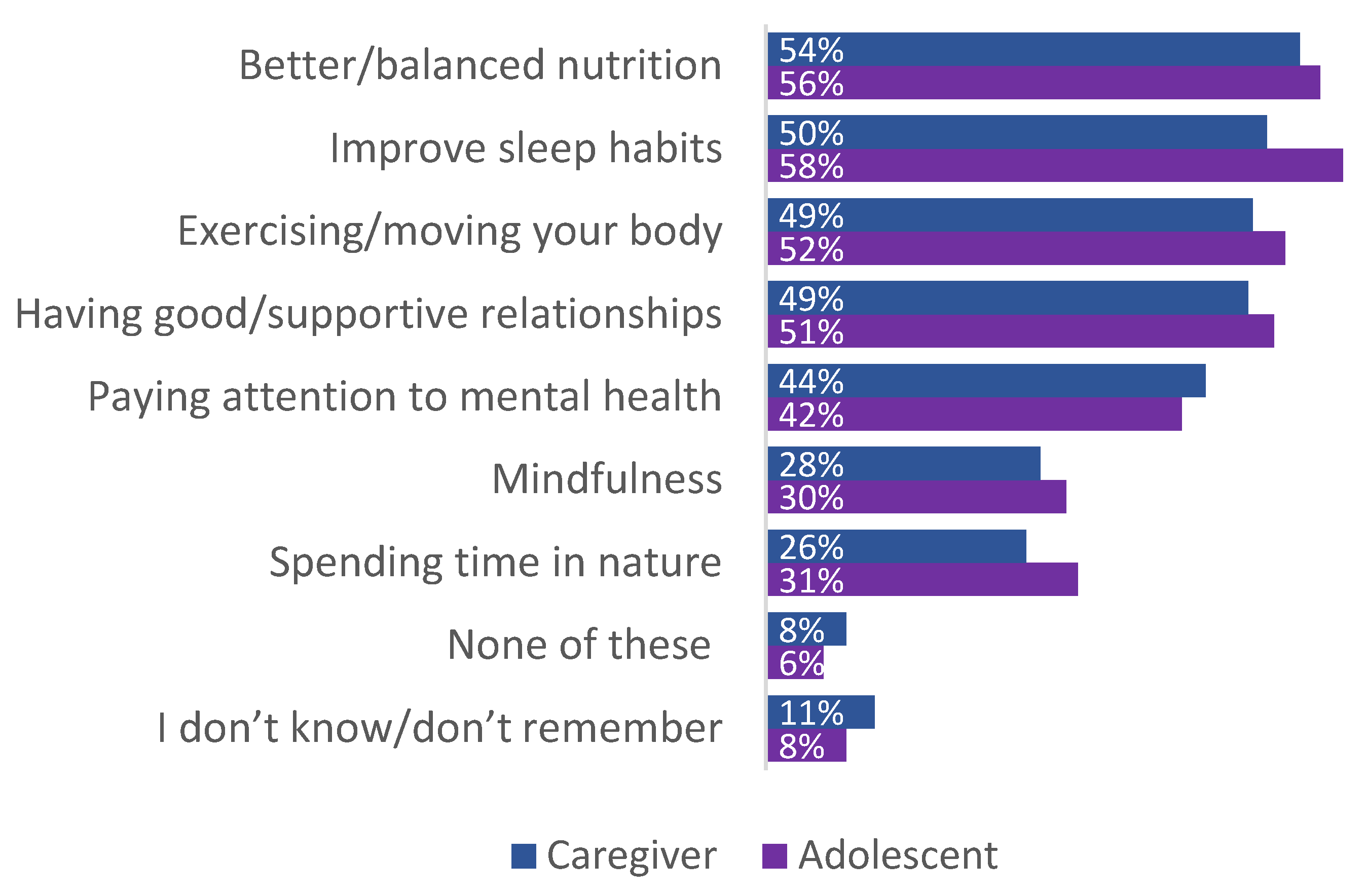

3.5. Responding to ACEs

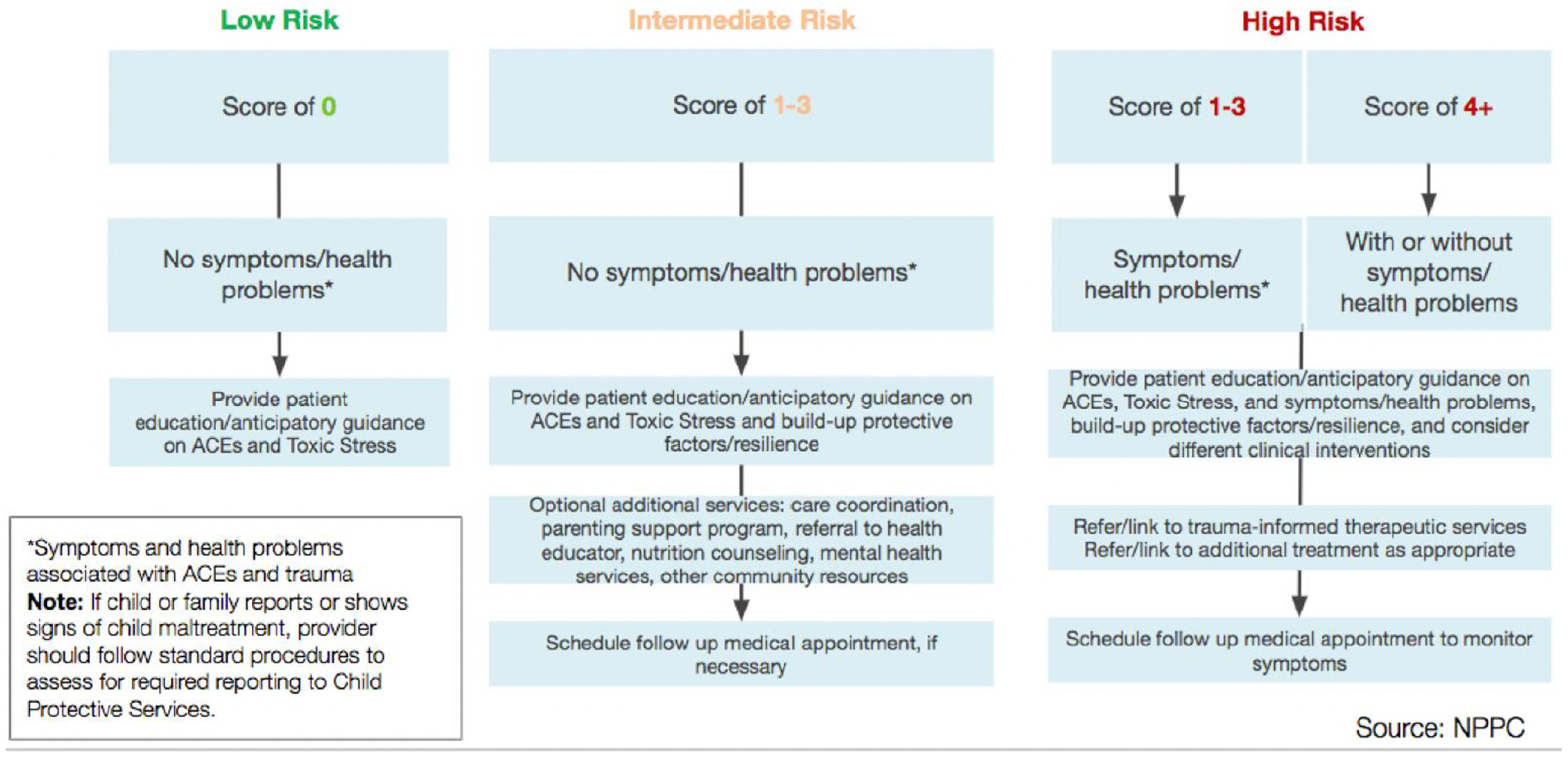

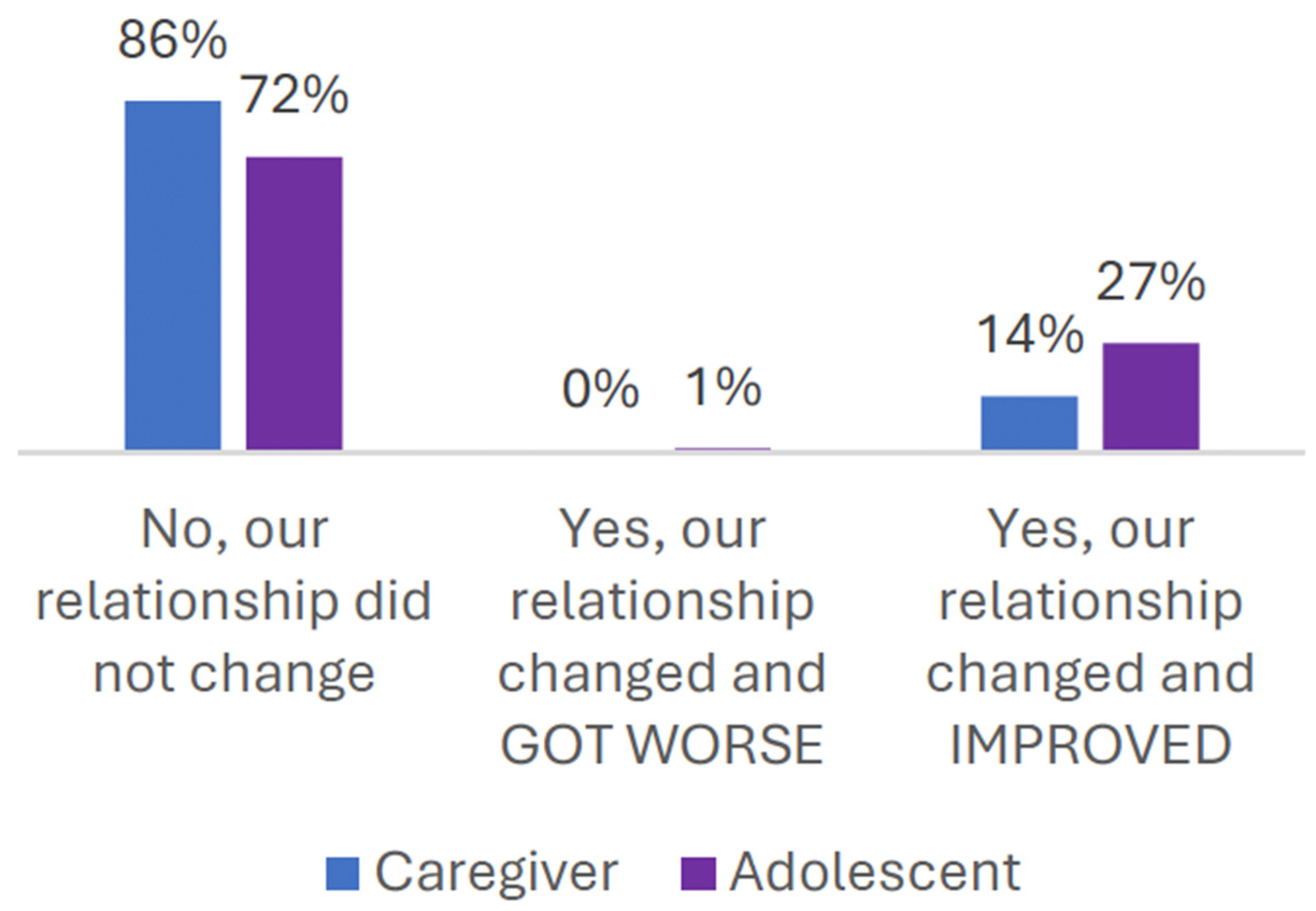

3.6. Patient/Caregiver Experiences

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Gilgoff, R.; Schwartz, T.; Owen, M.; Bhushan, D.; Burke Harris, N. Opportunities to Treat Toxic Stress. Pediatrics 2022, 151, e2021055591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, E.G.; Thompson, R.; Dubowitz, H.; Harvey, E.M.; English, D.J.; Proctor, L.J.; Runyan, D.K. Adverse childhood experiences and child health in early adolescence. JAMA Pediatr. 2013, 167, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, M.; Marques, S.S.; Oh, D.; Harris, N.B. Toxic Stress in Children and Adolescents. Adv Pediatr. 2016, 63, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bethell, C.D.; Newacheck, P.; Hawes, E.; Halfon, N. Adverse childhood experiences: Assessing the impact on health and school engagement and the mitigating role of resilience. Health Aff. 2014, 33, 2106–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caserta, M.T.; O’Connor, T.G.; Wyman, P.A.; Wang, H.; Moynihan, J.; Cross, W.; Tu, X.; Jin, X. The associations between psychosocial stress and the frequency of illness, and innate and adaptive immune function in children. Brain Behav. Immun. 2008, 22, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, P.; Jonson-Reid, M.; Stahlschmidt, M.J.; Drake, B.; Constantino, J. Child Maltreatment and Pediatric Health Outcomes: A Longitudinal Study of Low-income Children. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2010, 35, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, P.A.; Moynihan, J.; Eberly, S.; Cox, C.; Cross, W.; Jin, X.; Caserta, M.T. Association of family stress with natural killer cell activity and the frequency of illnesses in children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, R.; Flynn, H.; Hoffmann, R.; Vazquez, D.; Lopez, J.; Marcus, S. Early Developmental Changes in Sleep in Infants: The Impact of Maternal Depression. Sleep 2009, 32, 693–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolke, D.; Lereya, S.T. Bullying and parasomnias: A longitudinal cohort study. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e1040–e1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, M.A.; Alford, S.M.; Hinojosa, M.S.; Knapp, C.; Fernandez-Baca, D.E. Adverse childhood experiences and dental health in children and adolescents. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2015, 43, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, R.; Gjelsvik, A.; Nocera, M.; McQuaid, E.L. Association between adverse childhood experiences in the home and pediatric asthma. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015, 114, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Burke, N.J.; Hellman, J.L.; Scott, B.G.; Weems, C.F.; Carrion, V.G. The impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences on an urban pediatric population. Child Abus. Negl. 2011, 35, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stork, B.R.; Akselberg, N.J.; Qin, Y.; Miller, D.C. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Community Physicians: What We’ve Learned. Perm. J. 2020, 24, 19.099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerker, B.D.; Storfer-Isser, A.; Szilagyi, M.; Stein, R.E.; Garner, A.S.; O’Connor, K.G.; Hoagwood, K.E.; Horwitz, S.M. Do Pediatricians Ask About Adverse Childhood Experiences in Pediatric Primary Care? Acad. Pediatr. 2016, 16, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBain, R.K.; Levin, J.S.; Matthews, S.; Qureshi, N.; Long, D.; Schickedanz, A.B.; Gilgoff, R.; Kotz, K.; Slavich, G.M.; Eberhart, N.K. The effect of adverse childhood experience training, screening, and response in primary care: A systematic review. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 65, 102282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilgoff, R.; Singh, L.; Koita, K.; Gentile, B.; Marques, S.S. Adverse Childhood Experiences, outcomes, and interventions. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 67, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Office of the California Surgeon General. Roadmap for Resilience: The California Surgeon General’s Report on Adverse Childhood Experiences, Toxic Stress, and Health. Office of the California Surgeon General. 2020. Available online: https://osg.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/266/2020/12/Roadmap-For-Resilience_CA-Surgeon-Generals-Report-on-ACEs-Toxic-Stress-and-Health_12092020.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Machtinger, E.L.; Eberhart, N.K.; Ashwood, J.S.; Jones, M.; Sanchez, M.; Lightfoot, M.; Kuo, A.; Malika, N.; Leba, N.V.; Williamson, S.; et al. Clinic Readiness for Trauma-Informed Health Care Is Associated With Uptake of Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences. Perm. J. 2024, 110, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.R.; McCreary, M.; Ford, J.D.; Rahmanian Koushkaki, S.; Kenan, K.N.; Zima, B.T. Validation of the Traumatic Events Screening Inventory for ACEs. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20182546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, A.-M.; Szilagyi, M.A.; Jee, S.H.; Manly, J.T.; Briggs, R.; Szilagyi, P.G. Parental perspectives of screening for adverse childhood experiences in pediatric primary care. Fam. Syst. Health 2018, 36, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGangi, M.J.; Negriff, S. The implementation of screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences in pediatric primary care. J. Pediatr. 2020, 222, 174–179.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, T.; Alabaster, A.; McCaw, B.; Stoller, N.; Watson, C.; Young-Wolff, K.C. Feasibility and Acceptability of Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences in Prenatal Care. J. Womens Health 2018, 27, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowa, P.T.; Olson, A.L.; Johnson, D.J. Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences in a Family Medicine Setting: A Feasibility Study. J. Am. Board. Fam. Med. 2016, 29, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmakis, K.A.; Shafer, M.B.; Chandler, G.E.; Aponte, E.V.; Roberts, S.J. Screening for childhood adversity among adult primary care patients. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2018, 30, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kia-Keating, M.; Barnett, M.L.; Liu, S.R.; Sims, G.M.; Ruth, A.B. Trauma-Responsive Care in a Pediatric Setting: Feasibility and Acceptability of Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 64, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koita, K.; Long, D.; Hessler, D.; Benson, M.; Daley, K.; Bucci, M.; Thakur, N.; Burke Harris, N. Development and implementation of a pediatric adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and other determinants of health questionnaire in the pediatric medical home: A pilot study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie-Mitchell, A.; Lee, J.; Siplon, C.; Chan, F.; Riesen, S.; Vercio, C. Implementation of the Whole Child Assessment to Screen for Adverse Childhood Experiences. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2019, 6, 2333794X19862093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsicek, S.M.; Morrison, J.M.; Manikonda, N.; O’Halleran, M.; Spoehr-Labutta, Z.; Brinn, M. Implementing Standardized Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences in a Pediatric Resident Continuity Clinic. Pediatr. Qual. Saf. 2019, 4, e154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, K.; Ruiz, M.J.; Aschkenasy, J.; Chang, J.D.; Heard, A.; Minier, M.; Osta, A.D.; Pavelack, M.; Samelson, M.; Schwartz, A.; et al. Screening for Toxic Stress Risk Factors at Well-Child Visits: The Addressing Social Key Questions for Health Study. J. Pediatr. 2019, 205, 244–249.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.R.; Young-Wolff, K.C.; Negriff, S.; Dumke, K.; DiGangi, M. Implementation and Evaluation of Adverse Childhood Experiences Screening in Pediatrics and Obstetrics Settings. Perm. J. 2024, 28, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purewal, S.K.; Bucci, M.; Wang, L.G.; Koita, K.; Silvério Marques, S.; Oh, D.; Burke Harris, N. Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in an Integrated Pediatric Care Model. Zero Three 2016, 36, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, R.J. Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences in Pediatric Primary Care: Pitfalls and Possibilities. Pediatr. Ann. 2019, 48, e257–e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffee, S.R.; Bowes, L.; Ouellet-Morin, I.; Fisher, H.L.; Moffitt, T.E.; Merrick, M.T.; Arseneault, L. Safe, stable, nurturing relationships break the intergenerational cycle of abuse: A prospective nationally representative cohort of children in the United Kingdom. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, S4–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, A.; Yogman, M. Preventing Childhood Toxic Stress: Partnering With Families and Communities to Promote Relational Health. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2021052582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, A.S.; Shonkoff, J.P.; Siegel, B.S.; Dobbins, M.I.; Earls, M.F.; McGuinn, L.; Pascoe, J.; Wood, D.L. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: Translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e224–e231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luckett, K.M.; Gilgoff, R.; Peterson, M.; Hovde, A.; Pinney, S.; Gubernick, R.S.; Schafer, L.M.; Sanchez, M.; Kairys, S. A National Trauma-Informed Adverse Childhood Experience Screening and Intervention Evaluation Project. Children 2025, 12, 453. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040453

Luckett KM, Gilgoff R, Peterson M, Hovde A, Pinney S, Gubernick RS, Schafer LM, Sanchez M, Kairys S. A National Trauma-Informed Adverse Childhood Experience Screening and Intervention Evaluation Project. Children. 2025; 12(4):453. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040453

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuckett, Karissa M., Rachel Gilgoff, Molly Peterson, Aldina Hovde, Stephanie Pinney, Ruth S. Gubernick, Lisa M. Schafer, Monika Sanchez, and Steven Kairys. 2025. "A National Trauma-Informed Adverse Childhood Experience Screening and Intervention Evaluation Project" Children 12, no. 4: 453. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040453

APA StyleLuckett, K. M., Gilgoff, R., Peterson, M., Hovde, A., Pinney, S., Gubernick, R. S., Schafer, L. M., Sanchez, M., & Kairys, S. (2025). A National Trauma-Informed Adverse Childhood Experience Screening and Intervention Evaluation Project. Children, 12(4), 453. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040453