Improving Intensive End-of-Life Care for Infants and Children: A Scoping Review of Intervention Elements

Highlights

- Most interventions targeted clinician knowledge as a primary outcome, whereas fewer interventions targeted family outcomes.

- Few interventions utilized nursing workflows to improve end-of-life care in pediatric and neonatal critical care settings.

- Findings underscore the need for interventions that target family outcomes, especially parental empowerment.

- More interventions should assess family outcomes and aim to integrate families in development.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Criteria

2.4. Screening and Data Management

2.5. Data Extraction and Quality Appraisal

2.6. Analysis

3. Results

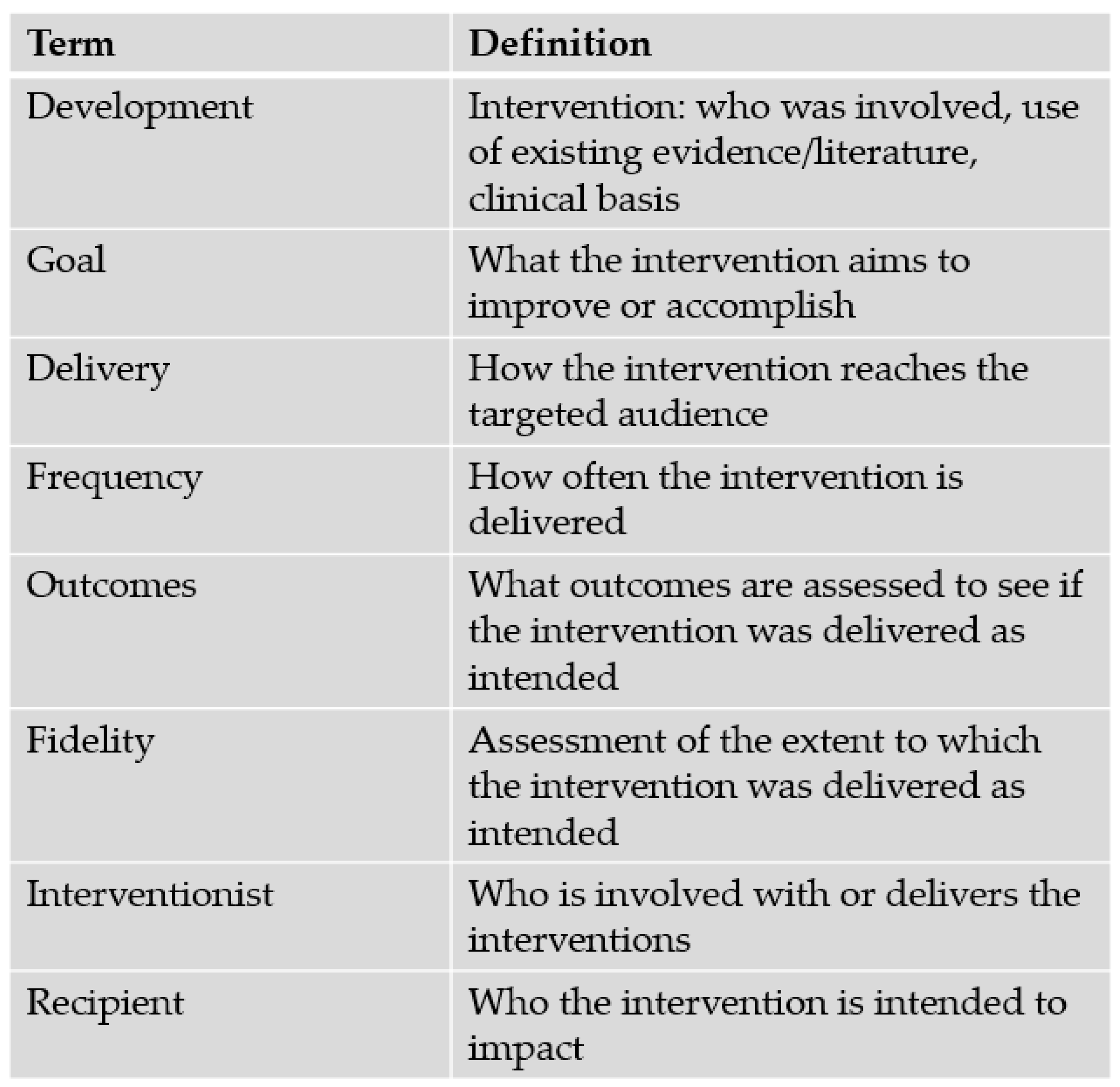

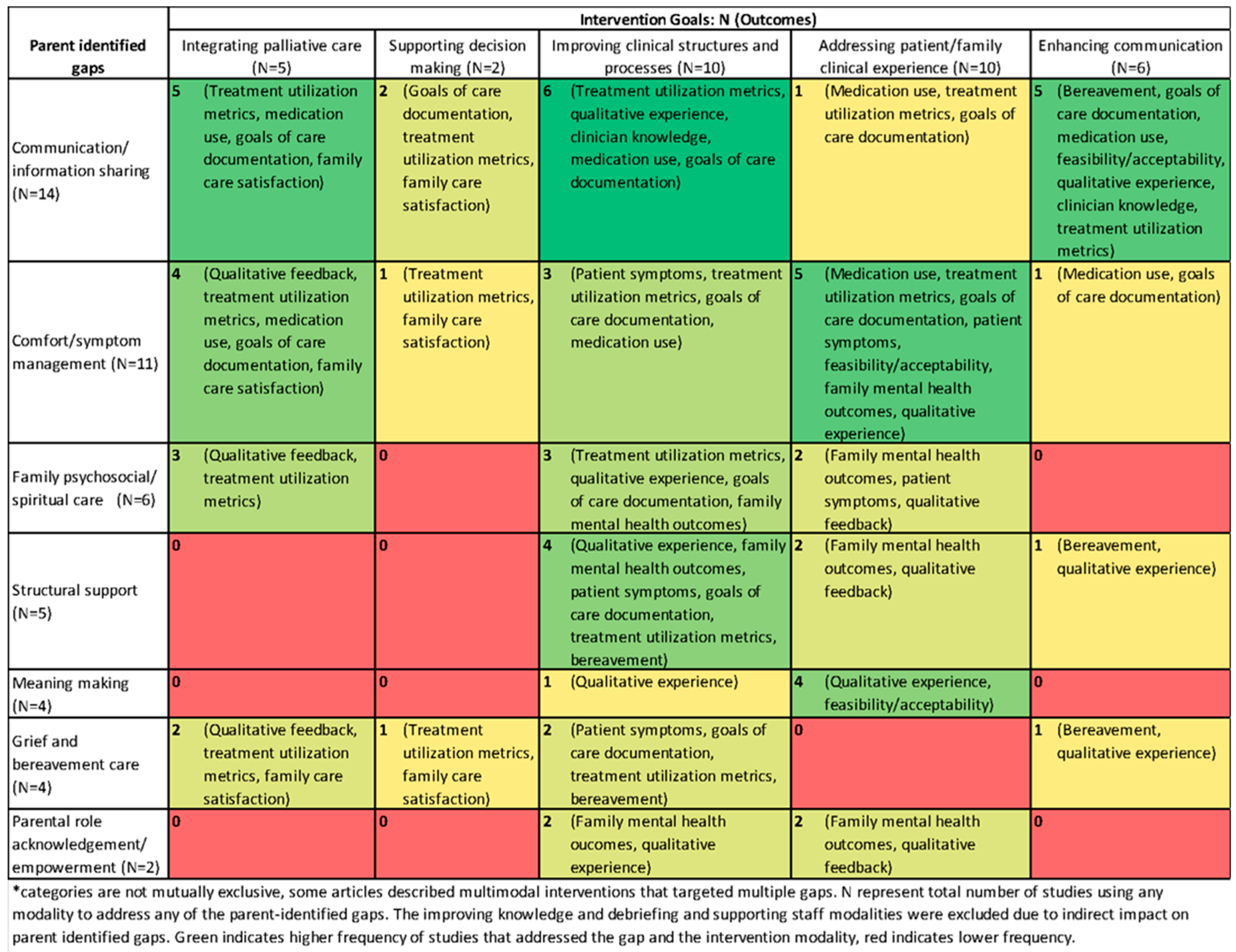

3.1. Intervention Elements

3.2. Contextual Factors

3.3. Implementation Barriers and Facilitators

3.4. Study Rigor

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

5.1. Strengths and Limitations of Included Studies

5.2. Strengths and Limitations of Review

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PICU | Pediatric Intensive Care Unit |

| EOL | End-of-life |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| NICU | Neonatal intensive care unit |

References

- Wheeler, I. Parental Bereavement: The Crisis of Meaning. Death Stud. 2001, 25, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klass, D. Parental Grief: Solace and Resolution; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988; ISBN 978-0-8261-5930-4. [Google Scholar]

- Snaman, J.M.; Morris, S.E.; Rosenberg, A.R.; Holder, R.; Baker, J.; Wolfe, J. Reconsidering Early Parental Grief Following the Death of a Child from Cancer: A New Framework for Future Research and Bereavement Support. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 4131–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broden, E.G.; Werner-Lin, A.; Curley, M.A.Q.; Hinds, P.S. Shifting and Intersecting Needs: Parents’ Experiences During and Following the Withdrawal of Life Sustaining Treatments in the PICU. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2022, 70, 103216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R. New Understandings of Parental Grief: Literature Review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 46, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannen, P.K.; Wolfe, J.; Prigerson, H.G.; Onelov, E.; Kreicbergs, U.C. Unresolved Grief in a National Sample of Bereaved Parents: Impaired Mental and Physical Health 4 to 9 Years Later. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 5870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meert, K.L.; Briller, S.; Schim, S.M.; Thurston, C.; Kabel, A. Examining the Needs of Bereaved Parents in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit: A Qualitative Study. Death Stud. 2009, 33, 712–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, K.M.; Alexander, P.M.A.; Schlapbach, L.J.; Millar, J.; Jacobe, S.; Ravindranathan, H.; Croston, E.J.; Staffa, S.J.; Burns, J.P.; Gelbart, B.; et al. Epidemiology of Childhood Death in Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Units. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45, 1262–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.P.; Sellers, D.E.; Meyer, E.C.; Lewis-Newby, M.; Truog, R.D. Epidemiology of Death in the PICU at Five U.S. Teaching Hospitals. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 42, 2101–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, K.M.; Lelkes, E.; Kumar, R.K.; DeCourcey, D.D. Is This as Good as It Gets? Implications of an Asymptotic Mortality Decline and Approaching the Nadir in Pediatric Intensive Care. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2021, 181, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, A.E.; Hall, H.; Copnell, B. The Changing Nature of Relationships between Parents and Healthcare Providers When a Child Dies in the Paediatric Intensive Care Unit. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooten, D.; Youngblut, J.M.; Seagrave, L.; Caicedo, C.; Hawthorne, D.; Hidalgo, I.; Roche, R. Parent’s Perceptions of Health Care Providers Actions around Child ICU Death: What Helped, What Did Not. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2013, 30, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adistie, F.; Neilson, S.; Shaw, K.L.; Bay, B.; Efstathiou, N. The Elements of End-of-Life Care Provision in Paediatric Intensive Care Units: A Systematic Integrative Review. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, P.-F.; Tseng, Y.-M.; Wang, C.-C.; Chen, Y.-J.; Huang, S.-H.; Hsu, T.-F.; Florczak, K.L. Nurses’ Experiences in End-of-Life Care in the PICU: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2019, 32, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L.; Fraser, L.; Noyes, J.; Taylor, J.; Hackett, J. Understanding Parent Experiences of End-of-Life Care for Children: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Palliat. Med. 2023, 37, 178–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezuka, S.; Kobayashi, K. Parental Experience of Child Death in the Paediatric Intensive Care Unit: A Scoping Review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e057489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, T.S.W.; Lee, J.H. Statistical Note: Using Scoping and Systematic Reviews. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 22, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. Implement. Sci. IS 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Grainger, M.J.; Gray, C.T. Citationchaser: An R Package and Shiny App for Forward and Backward Citations Chasing in Academic Searching. Zenedo 2021, 16, 10–5281. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J.L.; Kuriyama, A.; Anton, A.; Choi, A.; Fournier, J.-P.; Geier, A.-K.; Jacquerioz, F.; Kogan, D.; Scholcoff, C.; Sun, R. The Accuracy of Google Translate for Abstracting Data From Non–English-Language Trials for Systematic Reviews. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 677–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence—Better Systematic Review Management. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap Consortium: Building an International Community of Software Platform Partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—A Metadata-Driven Methodology and Workflow Process for Providing Translational Research Informatics Support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Reardon, C.M.; Opra Widerquist, M.A.; Lowery, J. Conceptualizing Outcomes for Use with the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): The CFIR Outcomes Addendum. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Reardon, C.M.; Widerquist, M.A.O.; Lowery, J. The Updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Based on User Feedback. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, C. Care of patients suffering from terminal illness at St. Joseph’s Hospice, Hackney, London. Nurs. Mirror 1964, 14, Xii-x. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Q.; Pluye, P.; Fabregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool; McGill University: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stata Statistical Software; Release 17; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2021.

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering Implementation of Health Services Research Findings into Practice: A Consolidated Framework for Advancing Implementation Science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedoose. Available online: https://www.dedoose.com/?gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAiAm-67BhBlEiwAEVftNqFH47mAqW8sT8QxIw-3DjbgoymUQpW2tedyXZuy09LVGGjecoyTVxoCyEgQAvD_BwE (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Butler, A.E.; Copnell, B.; Hall, H. When a Child Dies in the PICU: Practice Recommendations From a Qualitative Study of Bereaved Parents. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 20, e447–e451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morillo Palomo, A.; Clotet Caba, J.; Camprubi Camprubi, M.; Blanco Diez, E.; Silla Gil, J.; Riverola de Veciana, A. Implementing Palliative Care, Based on Family-Centered Care, in a Highly Complex Neonatal Unit. J. Pediatr. Rio J. 2023, 100, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, M.; Yokoo, K.; Ozawa, M.; Fujimoto, S.; Funaba, Y.; Hattori, M. Development of a Neonatal End-of-Life Care Education Program for NICU Nurses in Japan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. JOGNN NAACOG 2015, 44, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nellis, M.E.; Howell, J.D.; Ching, K.; Bylund, C. The Use of Simulation to Improve Resident Communication and Personal Experience at End-of-Life Care. J. Pediatr. Intensive Care 2017, 6, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parry, S.M.; Staenberg, B.; Weaver, M.S. Mindful Movement: Tai Chi, Gentle Yoga, and Qi Gong for Hospitalized Pediatric Palliative Care Patients and Family Members. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, 1212–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S.; Babgi, A.; Gomez, C. Educational Interventions in End-of-Life Care: Part I: An Educational Intervention Responding to the Moral Distress of NICU Nurses Provided by an Ethics Consultation Team. Adv. Neonatal Care 2008, 8, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheurer, J.M.; Norbie, E.; Bye, J.K.; Villacis-Calderon, D.; Heith, C.; Woll, A.; Shu, D.; McManimon, K.; Kamrath, H.; Goloff, N. Pediatric End-of-Life Care Skills Workshop: A Novel, Deliberate Practice Approach. Acad. Pediatr. 2023, 23, 860–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twamley, K.; Kelly, P.; Moss, R.; Mancini, A.; Craig, F.; Koh, M.; Polonsky, R.; Bluebond-Langner, M. Palliative Care Education in Neonatal Units: Impact on Knowledge and Attitudes. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2013, 3, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Tang, Q.; Zhu, L.H.; Peng, X.M.; Zhang, N.; Xiong, Y.E.; Chen, M.H.; Chen, K.L.; Luo, D.; Li, X.; et al. Testing a Family Supportive End of Life Care Intervention in a Chinese Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Quasi-Experimental Study with a Non-Randomized Controlled Trial Design. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 870382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhammad, S.; Almasri, R. Impact of Educational Programs on Nurses’ Knowledge and Attitude toward Pediatric Palliative Care. Palliat. Support. Care 2022, 20, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.D.; Shukla, R.; Baker, R.; Slaven, J.E.; Moody, K. Improving Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Providers’ Perceptions of Palliative Care through a Weekly Case-Based Discussion. Palliat. Med. Rep. 2021, 2, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuncion, A.M.; Cagande, C.; Schlagle, S.; McCarty, B.; Hunter, K.; Milcarek, B.; Staman, G.; Da Silva, S.; Fisher, D.; Graessle, W. A Curriculum to Improve Residents’ End-of-Life Communication and Pain Management Skills During Pediatrics Intensive Care Rotation: Pilot Study. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013, 5, 510–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.; Jackson, K.; Sheehy, K.A.; Finkel, J.C.; Quezado, Z.M. The Use of Dexmedetomidine in Pediatric Palliative Care: A Preliminary Study. J. Palliat. Med. 2017, 20, 779–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.L.; Placencia, F.X.; Arnold, J.L.; Minard, C.G.; Harris, T.B.; Haidet, P.M. A Structured End-of-Life Curriculum for Neonatal-Perinatal Postdoctoral Fellows. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2015, 32, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haut, C.M.; Michael, M.; Moloney-Harmon, P. Implementing a Program to Improve Pediatric and Pediatric ICU Nurses’ Knowledge of and Attitudes Toward Palliative Care. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2012, 14, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, K.; Goldstein, J.; Vessella, S.; Tucker, R.; Lechner, B.E. Providing Support for Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Health Care Professionals: A Bereavement Debriefing Program. Am. J. Perinatol. 2022, 39, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.E.; Kim, Y.H. Changes in the End-of-Life Process in Patients with Life-Limiting Diseases through the Intervention of the Pediatric Palliative Care Team. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaq, A.G.; Khalaf, S.M. Effect of Educational Program on Nurses’ Performance Regarding Neonatal Palliative Care. Tanta Sci. Nurs. J. 2016, 10, 43–71. [Google Scholar]

- Samsel, C.; Lechner, B.E. End-of-Life Care in a Regional Level IV Neonatal Intensive Care Unit after Implementation of a Palliative Care Initiative. J. Perinatol. 2015, 35, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Laksana, E.; McCrory, M.C.; Hsu, S.; Zhou, A.X.; Burkiewicz, K.; Ledbetter, D.R.; Aczon, M.D.; Shah, S.; Siegel, L.; et al. Analgesia and Sedation at Terminal Extubation: A Secondary Analysis from Death One Hour after Terminal Extubation Study Data. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 24, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesely, C.; Newman, V.; Winters, Y.; Flori, H. Bringing Home to the Hospital: Development of the Reflection Room and Provider Perspectives. J. Palliat. Med. 2017, 20, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younge, N.; Smith, P.B.; Goldberg, R.N.; Brandon, D.H.; Simmons, C.; Cotten, C.M.; Bidegain, M. Impact of a Palliative Care Program on End-of-Life Care in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J. Perinatol. 2015, 35, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, S.T.; Dixon, R.; Trozzi, M. The Wrap-up: A Unique Forum to Support Pediatric Residents When Faced with the Death of a Child. J. Palliat. Med. 2012, 15, 1329–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, B.S.; Guthrie, S.O. Utility of Morbidity and Mortality Conference in End-of-Life Education in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J. Palliat. Med. 2007, 10, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P.; Booth, D. Copying Medical Summaries on Deceased Infants to Bereaved Parents. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2011, 100, 1262–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, R.; Binoche, A.; Noizet, O.; Fourier, C.; Leteurtre, S.; Moutel, G.; Leclerc, F. Are the GFRUP’s Recommendations for Withholding or Withdrawing Treatments in Critically Ill Children Applicable? Results of a Two-Year Survey. J. Med. Ethics 2007, 33, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czynski, A.J.; Souza, M.; Lechner, B.E. The Mother Baby Comfort Care Pathway: The Development of a Rooming-In-Based Perinatal Palliative Care Program. Adv. Neonatal Care 2022, 22, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drolet, C.; Roy, H.; Laflamme, J.; Marcotte, M.-E. Feasibility of a Comfort Care Protocol Using Oral Transmucosal Medication Delivery in a Palliative Neonatal Population. J. Palliat. Med. 2016, 19, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.M.; Hamilton, M.F.; Watson, R.S.; Claxton, R.; Barnett, M.; Thompson, A.E.; Arnold, R. An Intensive, Simulation-Based Communication Course for Pediatric Critical Care Medicine Fellows. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 18, e348–e355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Corcoran, C.; Wawrzynski, S.E.; Mansfield, K.; Fuchs, E.; Yeates, C.; Flaherty, B.F.; Harousseau, M.; Cook, L.; Epps, J.V. Grieving Children’ Death in an Intensive Care Unit: Implementation of a Standardized Process. J. Palliat. Med. 2023, 27, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, S.L.; Ives-Baine, L. “Most Prized Possessions”: Photography as Living Relationships Within the End-of-Life Care of Newborns. Illn. Crisis Loss 2014, 22, 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meert, K.L.; Eggly, S.; Kavanaugh, K.; Berg, R.A.; Wessel, D.L.; Newth, C.J.L.; Shanley, T.P.; Harrison, R.; Dalton, H.; Michael Dean, J.; et al. Meaning Making during Parent-Physician Bereavement Meetings after a Child’s Death. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, R.J.; Glicken, A.D.; Siegel, R.R. Neonatal Loss in the Intensive Care Nursery. Effects of Maternal Grieving and a Program for Intervention. J. Am. Acad. Child Psychiatry 1984, 23, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kymre, I.G.; Bondas, T. Skin-to-Skin Care for Dying Preterm Newborns and Their Parents—A Phenomenological Study from the Perspective of NICU Nurses. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2013, 27, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J.; Bang, K.S. Development and Evaluation of a Self-Reflection Program for Intensive Care Unit Nurses Who Have Experienced the Death of Pediatric Patients. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2017, 47, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knighting, K.; Kirton, J.; Silverio, S.A.; Shaw, B.N.J. A Network Approach to Neonatal Palliative Care Education Impact on Knowledge, Efficacy, and Clinical Practice. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2019, 33, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolgar, F.; Archibald, S.-J. An Exploration of Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) Staff Experiences of Attending Pre-Brief and Debrief Groups Surrounding a Patient’s Death or Redirection of Care. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2021, 27, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbit, M.J.; Hill, M.; Peterson, N. A Comprehensive Pediatric Bereavement Program: The Patterns of Your Life. Crit. Care Nurs. Q. 1997, 20, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, C.H.; Reder, E.; Hall, B.; Comello, K.; Sellers, D.E.; Hutton, N. Interdisciplinary Interventions to Improve Pediatric Palliative Care and Reduce Health Care Professional Suffering. J. Palliat. Med. 2006, 9, 922–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, B.K.; Pendergrass, T.L.; Grooms, T.R.; Florez, A.R. End of Life Simulation in a Pediatric Cardiac Intensive Care Unit. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2021, 60, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, T.; Dorsett, C.; Connolly, A.; Kelly, N.; Turnbull, J.; Deorukhkar, A.; Clements, H.; Griffin, H.; Chhaochharia, A.; Haynes, S.; et al. Chameleon Project: A Children’s End-of-Life Care Quality Improvement Project. BMJ Open Qual. 2021, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amber, Q.; Lynn Zinkan, J.; Tofil, N.M.; White, M.L. Multidisciplinary Simulation in Pediatric Critical Care: The Death of a Child. Crit. Care Nurse 2012, 32, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, E.; Hayes, A.; Cerulli, L.; Miller, E.G.; Slamon, N. Legacy Building in Pediatric End-of-Life Care through Innovative Use of a Digital Stethoscope. Palliat. Med. Rep. 2020, 1, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas, J.; Jeppesen, A.; Peters, L.; Schuelke, T.; Magdoza, N.R.K.; Hesselgrave, J.; Loftis, L. Using Quality Improvement Science to Create a Navigator in the Electronic Health Record for the Consolidation of Patient Information Surrounding Pediatric End-of-Life Care. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, E218–E224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak Tayoob, M.; Rayala, S.; Doherty, M.; Singh, H.B.; Alimelu, M.; Lingaldinna, S.; Palat, G. Palliative Care for Newborns in India: Patterns of Care in a Neonatal Palliative Care Program at a Tertiary Government Children’s Hospital. Health Serv. Insights 2024, 17, 11786329231222858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, S.R.; Thienprayoon, R. Pediatric Palliative Care in the Intensive Care Unit and Questions of Quality: A Review of the Determinants and Mechanisms of High-Quality Palliative Care in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU). Transl. Pediatr. 2018, 7, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boss, R.; Nelson, J.; Weissman, D.; Campbell, M.; Curtis, R.; Frontera, J.; Gabriel, M.; Lustbader, D.; Mosenthal, A.; Mulkerin, C.; et al. Integrating Palliative Care into the PICU: A Report from the Improving Palliative Care in the ICU Advisory Board. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 15, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, S.; Chua, C. Nurses and Nursing Students’ Experiences on Pediatric End-of-Life Care and Death: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 112, 105332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, K.A.; Middleton, A.A.; Farley, A.A.; Henderson, N.E.; Peterson, E.B. End-of-Life Care Education in Pediatric Critical Care Medicine Fellowship Programs: Exploring Fellow and Program Director Perspectives. J. Palliat. Med. 2023, 26, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirani, R.; Khuram, H.; Elahi, A.; Maddox, P.A.; Pandit, M.; Issani, A.; Etienne, M. The Need for Improved End-of-Life Care Medical Education: Causes, Consequences, and Strategies for Enhancement and Integration. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2024, 41, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Smothers, A.; Fang, W.; Borland, M. Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Perception of End-of-Life Care Education Placement in the Nursing Curriculum. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2019, 21, E12–E18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.A.; Foito, K. Pediatric End-of-Life Simulation: Preparing the Future Nurse to Care for the Needs of the Child and Family. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 44, e9–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, M.M.; DeGrazia, M.; Mott, S.; Taylor, M.; Manning, M.J.; O’Brien, M.; Schenkel, S.R.; Cole, A.; Hickey, P.A. Utilizing High-Fidelity Simulation to Improve Newly Licensed Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Nurses’ Experiences with End-of-Life Care. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 27, e12360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods-Hill, C.Z.; Wolfe, H.; Malone, S.; Steffen, K.M.; Agulnik, A.; Flaherty, B.F.; Barbaro, R.P.; Dewan, M.; Kudchadkar, S. Implementation Science Research in Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 24, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ista, E.; van Dijk, M. Moving Away From Randomized Controlled Trials to Hybrid Implementation Studies for Complex Interventions in the PICU. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 25, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, K.M.; Holdsworth, L.M.; Ford, M.A.; Lee, G.M.; Asch, S.M.; Proctor, E.K. Implementation of Clinical Practice Changes in the PICU: A Qualitative Study Using and Refining the iPARIHS Framework. Implement. Sci. 2021, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, A.E.; Hall, H.; Copnell, B. Becoming a Team: The Nature of the Parent-Healthcare Provider Relationship When a Child Is Dying in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. J. Pediatr. Nurs. Nurs. Care Child. Fam. 2018, 40, e26–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barratt, M.; Bail, K.; Lewis, P.; Paterson, C. Nurse Experiences of Partnership Nursing When Caring for Children with Long-Term Conditions and Their Families: A Qualitative Systematic Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 932–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 44 | |

| Study design | Mixed Methods | 3 (7%) |

| Other 1 | 8 (18%) | |

| Qualitative | 4 (9%) | |

| Quantitative descriptive | 12 (27%) | |

| Quantitative non-randomized | 17 (39%) | |

| Unit type 2 | General PICU | 10 (23%) |

| PCICU | 4 (9%) | |

| NICU | 28 (64%) | |

| Other unit type | 2 (5%) | |

| Palliative care domains * | Physical | 34 (77%) |

| Physical alone | 5 (11%) | |

| Emotional/psychological | 38 (86%) | |

| Emotional alone | 1 (2%) | |

| Spiritual Domain | 25 (57%) | |

| Spiritual alone | 0 | |

| Social Domain | 30 (68%) | |

| Social Alone | 0 | |

| Multiple | 38 (86%) | |

| Interventionist Role 3 | Interprofessional team + family | 2 (5%) |

| Research team | 4 (10%) | |

| Supportive care consultants | 7 (17%) | |

| Physician | 6 (14%) | |

| Nurse | 3 (7%) | |

| Interprofessional team | 10 (24%) | |

| ICU clinical team | 5 (12%) | |

| Palliative care team | 2 (5%) | |

| External education team | 3 (7%) | |

| Nurse(s) involved | 18 (41%) | |

| Sample * | Patients | 14 (32%) |

| Parent/family | 10 (23%) | |

| Clinicians | 28 (64%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Broden Arciprete, E.G.; Ouyang, N.; Wawrzynski, S.E.; Eche-Ugwu, I.J.; Batten, J.; Costa, D.K.; Feder, S.L.; Snaman, J.M. Improving Intensive End-of-Life Care for Infants and Children: A Scoping Review of Intervention Elements. Children 2025, 12, 1485. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111485

Broden Arciprete EG, Ouyang N, Wawrzynski SE, Eche-Ugwu IJ, Batten J, Costa DK, Feder SL, Snaman JM. Improving Intensive End-of-Life Care for Infants and Children: A Scoping Review of Intervention Elements. Children. 2025; 12(11):1485. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111485

Chicago/Turabian StyleBroden Arciprete, Elizabeth G., Na Ouyang, Sarah E. Wawrzynski, Ijeoma J. Eche-Ugwu, Janene Batten, Deena K. Costa, Shelli L. Feder, and Jennifer M. Snaman. 2025. "Improving Intensive End-of-Life Care for Infants and Children: A Scoping Review of Intervention Elements" Children 12, no. 11: 1485. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111485

APA StyleBroden Arciprete, E. G., Ouyang, N., Wawrzynski, S. E., Eche-Ugwu, I. J., Batten, J., Costa, D. K., Feder, S. L., & Snaman, J. M. (2025). Improving Intensive End-of-Life Care for Infants and Children: A Scoping Review of Intervention Elements. Children, 12(11), 1485. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111485