Effects of Maternal Depression and Sensitivity on Infant Emotion Regulation: The Role of Context

Highlights

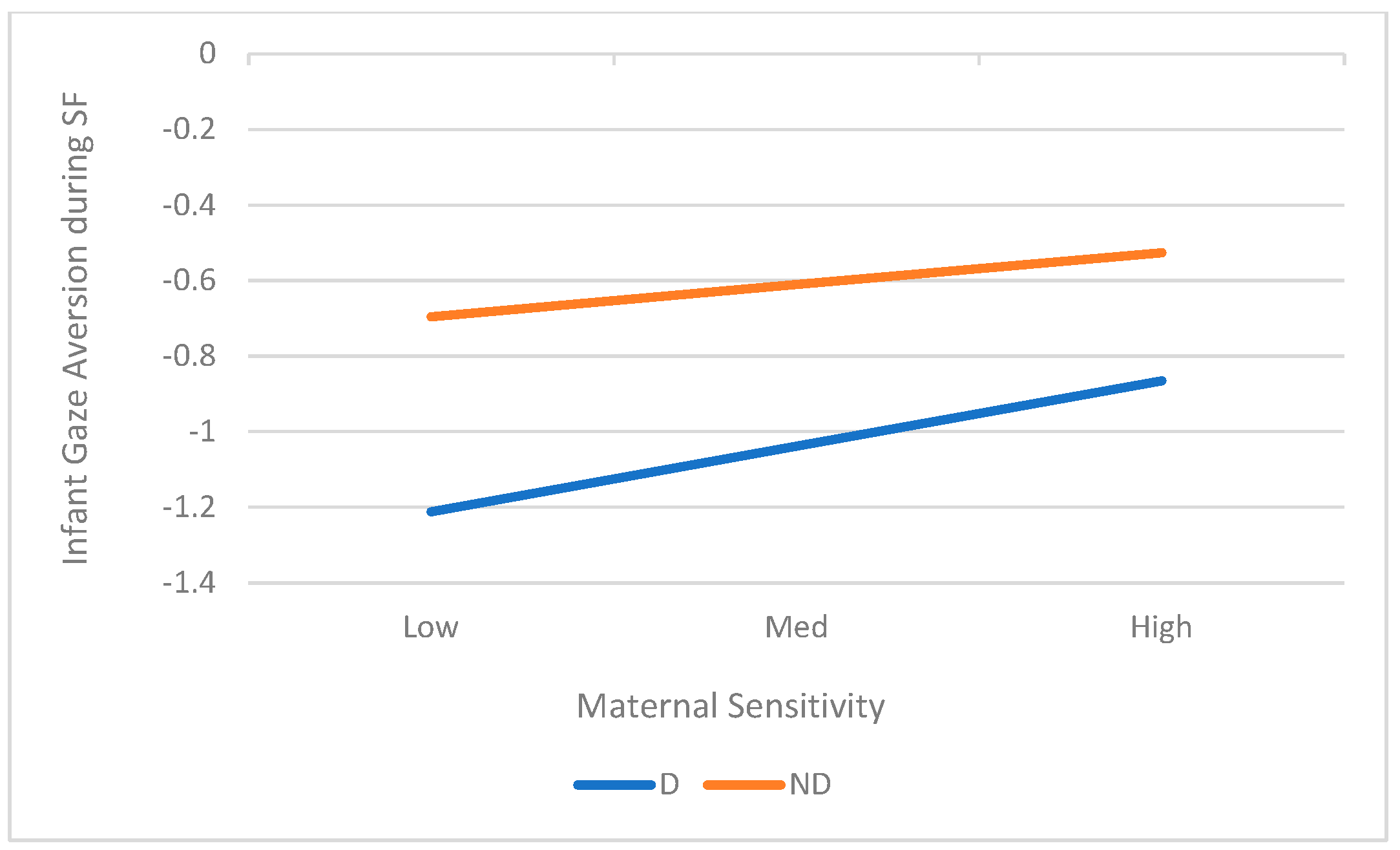

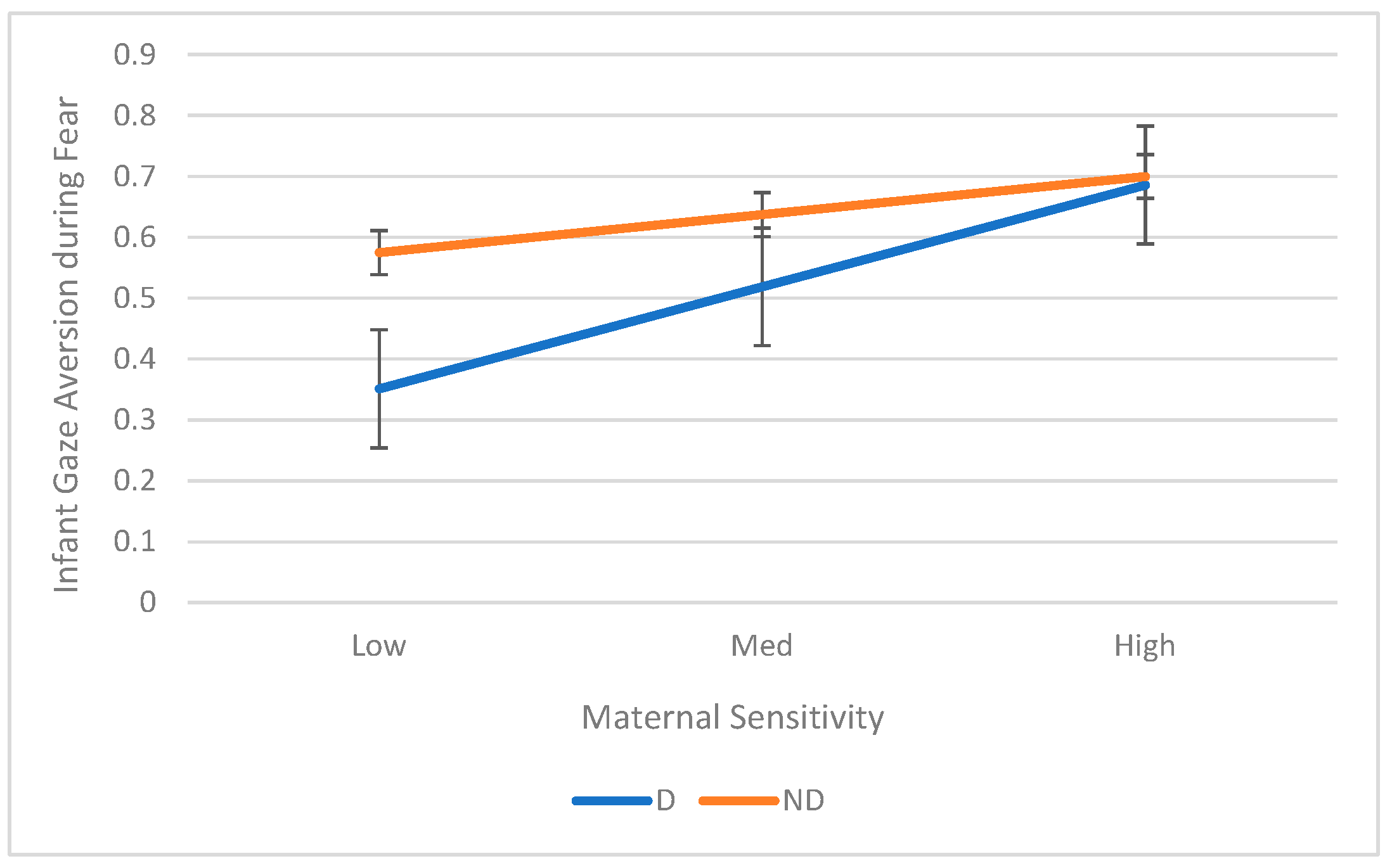

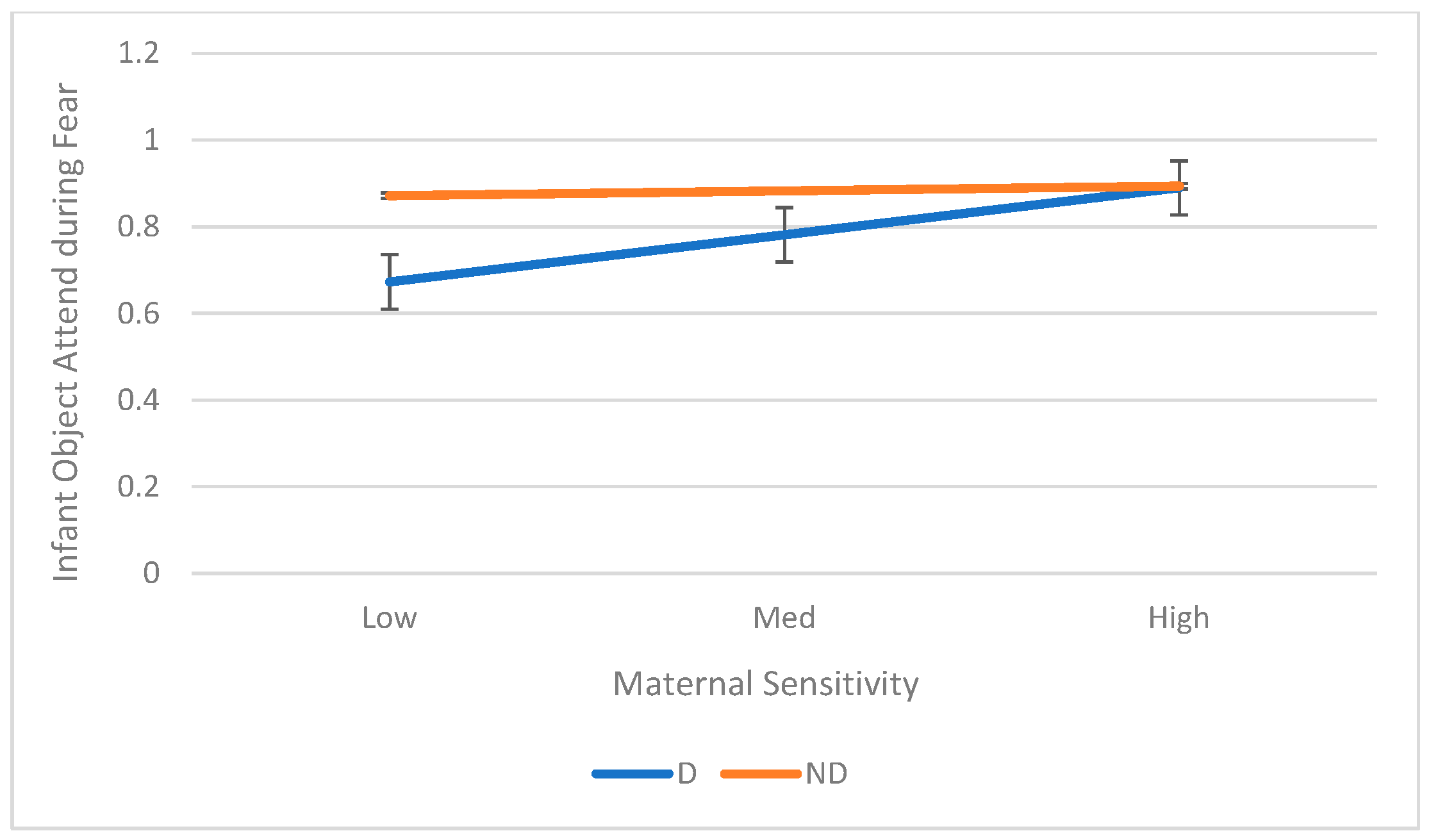

- Maternal sensitivity moderated the association between maternal depression and infant gaze aversion during the still-face episode with the mother and both gaze avert and object-attend during a Fear task as early as 5 months of age.

- The context of the stressor mattered, especially for infants of depressed mothers; they showed reduced use of the self-soothing strategy in the high-arousal fear task, which was a different pattern from their behavior in the still-face paradigm.

- Different types of regulatory behaviors might be important and effective for infants in different contexts, including high and low arousal, as well as social and non-social settings.

- Interventions aimed at improving maternal sensitivity—the ability to respond warmly and contingently to her infant’s cues—could be an effective way to improve emotion regulation in infants who are at risk due to maternal depression

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Emotion Regulation in Infancy

1.2. Maternal Depression and Infant ER

1.3. Maternal Sensitivity and Infant ER

1.4. Context in Infant ER

1.5. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Data Coding and Scoring

2.3.1. Maternal Sensitivity

2.3.2. SFP

2.3.3. Fear

3. Results

3.1. Aim 1: Main Effects of Maternal Depression on Infant ER

3.2. Aim 2: Associations Between Maternal Sensitivity Infant ER

3.3. Aim 3: Maternal Sensitivity as a Moderator of the Relation Between Maternal Depression and Infant ER

3.4. Aim 4: Role of Context on Infant ER

4. Discussion

5. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SFP | Still-Face Paradigm |

| ER | Emotion Regulation |

| PPD | Postpartum Depression |

References

- Asselmann, E.; Venz, J.; Wittchen, H.-U.; Martini, J. Maternal anxiety and depressive disorders prior to, during and after pregnancy and infant interaction behaviors during the Face-to-Face Still Face Paradigm at 4 months postpartum: A prospective-longitudinal study. Early Hum. Dev. 2018, 122, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, N.; Fassett, M.J.; Oyelese, Y.; Mensah, N.A.; Chiu, V.Y.; Yeh, M.; Peltier, M.R.; Getahun, D. Trends in postpartum depression by race, ethnicity, and prepregnancy body mass index. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2446486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, K.; Nissim, G.; Vaccaro, S.; Harris, J.L.; Lindhiem, O. Association between maternal depression and maternal sensitivity from birth to 12 months: A meta-analysis. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2018, 20, 578–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnick, D.L.; Sundaram, R.; Bell, E.M.; Ghassabian, A.; Goldstein, R.B.; Robinson, S.L.; Vafai, Y.; Gilman, S.E.; Yeung, E. Trajectories of maternal postpartum depressive symptoms. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20200857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Manian, N.; Henry, L.M. Clinically depressed and typically developing mother–infant dyads: Domain base rates and correspondences, relationship contingencies and attunement. Infancy 2021, 26, 877–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calkins, S.D. Regulatory competence and early disruptive behavior problems: The role of physiological regulation. In Biopsychosocial Regulatory Processes in the Development of Childhood Behavioral Problems; Olson, S.L., Sameroff, A.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; pp. 86–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.B.; Brownell, C.A.; Hungerford, A.; Spieker, S.J.; Mohan, R.; Blessing, J.S. The course of maternal depressive symptoms and maternal sensitivity as predictors of attachment security at 36 months. Dev. Psychopathol. 2004, 16, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, P.M.; Zahn-Waxler, C. Emotional dysregulation in disruptive behavior disorders. In Developmental Perspectives on Depression; Cicchetti, D., Toth, S.L., Eds.; University of Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 173–209. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, K.A.; Blissett, J.; Antoniou, E.E.; Zeegers, M.P.; McCleery, J.P. Effects of maternal depression in the Still-Face Paradigm: A meta-analysis. Infant Behav. Dev. 2018, 50, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.S.; Silk, J.S.; Steinberg, L.; Myers, S.S.; Robinson, L.R. The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Soc. Dev. 2007, 16, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.A. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1994, 59, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Gazelle, H. Development of infant high-intensity fear and fear regulation from 6 to 24 months: Maternal sensitivity and depressive symptoms as moderators. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2021, 49, 1473–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozicevic, L.; De Pascalis, L.; Schuitmaker, N.; Tomlinson, M.; Cooper, P.J.; Murray, L. Longitudinal association between child emotion regulation and aggression, and the role of parenting: A comparison of three cultures. Psychopathology 2016, 49, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, C.B. Regulation of distress and negative emotions: A developmental view. Dev. Psychol. 1989, 25, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, P.M.; Martin, S.E.; Dennis, T.A. Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Fabes, R.A. Emotion Regulation and Children’s Socioemotional Competence. In Child Psychology: A Handbook of Contemporary Issues; Balter, L., Tamis-LeMonda, C.S., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 357–381. [Google Scholar]

- Stifter, C.; Augustine, M. Emotion regulation. In Handbook of Emotional Development; LoBue, V., Pérez-Edgar, K., Buss, K.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Spinrad, T.L.; Eggum, N.D. Emotion-related self-regulation and its relation to children’s maladjustment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 6, 495–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, P.M.; Michel, M.K.; Teti, L.O. The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1994, 59, 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, S.L.; Rogosch, F.A.; Manly, J.T.; Cicchetti, D. The efficacy of toddler-parent psychotherapy to reorganize attachment in the young offspring of mothers with major depressive disorder: A randomized preventive trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 74, 1006–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stifter, C.A.; Spinrad, T.; Braungart-Rieker, J. Toward a developmental model of child compliance: The role of emotion regulation in infancy. Child Dev. 1999, 70, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sroufe, L.A. Emotional Development: The Organization of Emotional Life in the Early Years; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.A.; Hill-Soderlund, A.L.; Propper, C.B.; Calkins, S.D.; Mills-Koonce, W.R.; Cox, M.J. Mother–infant vagal regulation in the face-to-face still-face paradigm is moderated by maternal sensitivity. Child Dev. 2009, 80, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, G.A.; Calkins, S.D. Infants’ vagal regulation in the still-face paradigm is related to dyadic coordination of mother-infant interaction. Dev. Psychol. 2004, 40, 1068–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernier, A.; Carlson, S.M.; Whipple, N. From external regulation to self-regulation: Early parenting precursors of young children’s executive functioning. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, M.; Beeghly, M.; Moreira, J.; Tronick, E.; Fuertes, M. Emerging patterns of infant regulatory behavior in the Still-Face paradigm at 3 and 9 months predict mother-infant attachment at 12 months. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2021, 23, 814–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, M.; Santos, P.L.D.; Beeghly, M.; Tronick, E. More than maternal sensitivity shapes attachment. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1094, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, M.; Lopes-dos-Santos, P.; Beeghly, M.; Tronick, E. Infant coping and maternal interactive behavior predict attachment in a portuguese sample of healthy preterm infants. Eur. Psychol. 2009, 14, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesman, J.; Van IJzendoorn, M.H.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J. The many faces of the Still-Face Paradigm: A review and meta-analysis. Dev. Rev. 2009, 29, 120–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, K.; Sarkar, P.; Glover, V.; O’Connor, T.G. Quality of child–parent attachment moderates the impact of antenatal stress on child fearfulness. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, K.A.; Goldsmith, H.H. Fear and anger regulation in infancy: Effects on the temporal dynamics of affective expression. Child Dev. 1998, 69, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, R.; Granat, A.; Pariente, C.; Kanety, H.; Kuint, J.; Gilboa-Schechtman, E. Maternal depression and anxiety across the postpartum year and infant social engagement, fear regulation, and stress reactivity. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 48, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, C.; Rothbart, M.; Posner, M. Distress and attention interactions in early infancy. Motiv. Emot. 1997, 21, 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Braungart-Rieker, J.M.; Hill-Soderlund, A.L.; Karrass, J. Fear and anger reactivity trajectories from 4 to 16 months: The roles of temperament, regulation, and maternal sensitivity. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 46, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiel, E.J.; Price, N.N.; Premo, J.E. Maternal comforting behavior, toddlers’ dysregulated fear, and toddlers’ emotion regulatory behaviors. Emotion 2020, 20, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glöggler, B.; Pauli-Pott, U. Different fear-regulation behaviors in toddlerhood: Relations to preceding infant negative emotionality, maternal depression, and sensitivity. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2008, 54, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzetti, S.; Spinelli, M.; Coppola, G.; Lionetti, F.; D’Urso, G.; Shah, P.; Fasolo, M.; Aureli, T. Emotion regulation in toddlerhood: Regulatory strategies in anger and fear eliciting contexts at 24 and 30 months. Children 2023, 10, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronick, E.; Als, H.; Adamson, L.; Wise, S.; Brazelton, T.B. The infant’s response to entrapment between contradictory messages in face-to-face interaction. J. Am. Acad. Child Psychiatry 1978, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, C.; Murray, L.; Stein, A. The effect of postnatal depression on mother–infant interaction, infant response to the Still-face perturbation, and performance on an Instrumental Learning task. Dev. Psychopathol. 2004, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manian, N.; Bornstein, M.H. Dynamics of emotion regulation in infants of clinically depressed and nondepressed mothers. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2009, 50, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, T.; Vega-Lahr, N.; Scafidi, F.; Goldstein, S. Effects of maternal unavailability on mother-infant interactions. Infant Behav. Dev. 1986, 9, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, L.; Trevarthen, C. Emotional regulation of interactions between two-month-olds and their mothers. In Social Perception in Infants; Field, T.M., Fox, N.A., Eds.; Ablex: Auckland, New Zealand, 1985; pp. 177–197. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, M.K.; Beeghly, M.; Olson, K.L.; Tronick, E. Effects of maternal depression and panic disorder on mother-infant interactive behavior in the face-to-face still-face paradigm. Infant Ment. Health J. 2008, 29, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, T. The effects of mother’s physical and emotional unavailability on emotion regulation. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1994, 59, 208–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianino, A.; Tronick, E.Z. The mutual regulation model: The infant’s self and interactive regulation and coping defense capacities. In Stress and Coping Across Development; Field, T.M., McCabe, P., Schneiderman, N., Eds.; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 1988; pp. 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, M.K.; Tronick, E.Z. Infant affective reactions to the resumption of maternal interaction after the still-face. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silk, J.S.; Shaw, D.S.; Skuban, E.M.; Oland, A.A.; Kovacs, M. Emotion regulation strategies in offspring of childhood-onset depressed mothers. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2006, 47, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.H.; Gotlib, I.H. (Eds.) Children of Depressed Parents: Mechanisms of Risk and Implications for Treatment; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Shaw, D.S.; Kovacs, M.; Lane, T.; O’Rourke, F.E.; Alarcon, J.H. Emotion regulation in preschoolers: The roles of behavioral inhibition, maternal affective behavior, and maternal depression. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Feng, X.; Gerhardt, M.; Wang, L. Maternal depressive symptoms, rumination, and child emotion regulation. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.H.; Gotlib, I.H. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 106, 458–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Cumberland, A.; Spinrad, T.L. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychol. Inq. 1998, 9, 241–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T.; Diego, M.; Hernandez-Reif, M. Depressed mothers’ infants are less responsive to faces and voices. Infant Behav. Dev. 2009, 32, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T.; Hernandez-Reif, M.; Diego, M.; Feijo, L.; Vera, Y.; Gil, K.; Sanders, C. Still-face and separation effects on depressed mother-infant interactions. Infant Ment. Health J. Infancy Early Child. 2007, 28, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, E.E.; Cohn, J.F.; Allen, N.B.; Lewinsohn, P.M. Infant affect during parent—Infant interaction at 3 and 6 months: Differences between mothers and fathers and influence of parent history of depression. Infancy 2004, 5, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, K.M.; Olson, K.L.; Beeghly, M.; Tronick, E.Z. Making up is hard to do, especially for mothers with high levels of depressive symptoms and their infant sons. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2006, 47, 670–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.A.; Cohn, J.F.; Campbell, S.B. Infant affective responses to mother’s still face at 6 months differentially predict externalizing and internalizing behaviors at 18 months. Dev. Psychol. 2001, 37, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez-Nogueras, M.; Field, T.M.; Hossain, Z.; Pickens, J. Depressed mothers’ touching increases infants’ positive affect and attention in still-face interactions. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 1780–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, D.; Toth, S.L. Developmental psychopathology and disorders of affect. In Developmental Psychopathology, Vol. 2: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation; Cicchetti, D., Cohen, D.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 1995; pp. 369–420. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, E.M.; Cicchetti, D. Toward a transactional model of relations between attachment and depression. In Attachment in the Preschool Years: Theory, Research, and Intervention; Greenberg, M.T., Cicchetti, D., Cummings, E.M., Eds.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1990; pp. 339–372. [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy, M.C.; Graczyk, P.A.; O’Hare, E.; Neuman, G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 20, 561–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, R.; Eidelman, A.I. Maternal postpartum behavior and the emergence of infant–mother and infant–father synchrony in preterm and full-term infants: The role of neonatal vagal tone. Dev. Psychobiol. 2007, 49, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabulsy, G.M.; Provost, M.A.; Deslandes, J.; St-Laurent, D.; Moss, E.; Lemelin, J.-P.; Bernier, A.; Dassylva, J.-F. Individual differences in infant still-face response at 6 months. Infant Behav. Dev. 2003, 26, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, E.L.; Stack, D.M.; Lazimbat, O.K.; Bouchard, S.; Field, T.M. Co-regulation, relationship quality, and infant distress vocalizations observed during mother-infant interactions: Influences of maternal depression and different contexts. Infancy 2024, 29, 933–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.C.; Letourneau, N.; Campbell, T.S.; Tomfohr-Madsen, L.; Giesbrecht, G.F.; APrON Study Team. Developmental origins of infant emotion regulation: Mediation by temperamental negativity and moderation by maternal sensitivity. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, M.L.; Mangelsdorf, S.C. Behavioral strategies for emotion regulation in toddlers: Associations with maternal involvement and emotional expressions. Infant Behav. Dev. 1999, 22, 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekas, N.V.; Lickenbrock, D.M.; Braungart-Rieker, J.M. Developmental trajectories of emotion regulation across infancy: Do age and the social partner influence temporal patterns. Infancy 2013, 18, 729–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelaez, M.; Virues-Ortega, J.; Field, T.M.; Amir-Kiaei, Y.; Schnerch, G. Social referencing in infants of mothers with symptoms of depression. Infant Behav. Dev. 2013, 36, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Feng, X. Infant emotion regulation and cortisol response during the first 2 years of life: Association with maternal parenting profiles. Dev. Psychobiol. 2020, 62, 1076–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G. Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI-II) [Database Record]. APA PsycTests. 1996. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft00742-000 (accessed on 26 September 2001).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Manian, N.; Schmidt, E.; Bornstein, M.H.; Martinez, P. Factor structure and clinical utility of BDI-II factor scores in postpartum women. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 149, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, M.B.; Spitzer, R.L.; Gibbon, M.; Williams, J.B. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders—Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, 2/2001 Revision); Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, J.F.; Tronick, E.Z. Three-month-old infants’ reaction to simulated maternal depression. Child Dev. 1983, 54, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, H.; Rothbart, M. Prelocomotor and Locomotor Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery, Lab-TAB; Version 3.0. Technical Manual; Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Planalp, E.M.; Goldsmith, H.H. Observed profiles of infant temperament: Stability, heritability, and associations with parenting. Child Dev. 2020, 91, e563–e580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbart, M.K. Longitudinal observation of infant temperament. Dev. Psychol. 1986, 22, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowles, D.C.; Kochanska, G.; Murray, K. Electrodermal activity and temperament in preschool children. Psychophysiology 2000, 37, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, S.P.; Stifter, C.A. Development of approach and inhibition in the first year: Parallel findings from motor behavior, temperament ratings and directional cardiac response. Dev. Sci. 2002, 5, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Putnick, D.L.; Esposito, G. The nature and structure of mothers’ parenting their infants. Parenting 2022, 22, 83–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Putnick, D.L.; Esposito, G.; Pearson, R.M. The nature and structure of maternal parenting practices and infant behaviors in U.S. national and international samples. Front. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 2, 1124037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol. Bull. 1968, 70, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, A.A.; Clark, V. Computer-Aided Multivariate Analysis; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Tronick, E.Z.; Weinberg, M.K. The Infant Regulatory Scoring System (IRSS); Unpublished Manuscript; Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School: Boston, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Izard, C.E.; Dougherty, L.M. System for Identifying Affect Expressions by Holistic Judgments (AFFEX); Instructional Resources Center, University of Delaware: Newark, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Stifter, C.A.; Braungart, J.M. The regulation of negative reactivity in infancy: Function and development. Dev. Psychol. 1995, 31, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, A.; Poojari, S.; Varsha, K. Assessing the robustness of normality tests under varying skewness and kurtosis: A practical checklist for public health researchers. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2025, 25, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granat, A.; Gadassi, R.; Gilboa-Schechtman, E.; Feldman, R. Maternal depression and anxiety, social synchrony, and infant regulation of negative and positive emotions. Emotion 2017, 17, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leerkes, E.M.; Blankson, A.N.; O’Brien, M. Differential effects of maternal sensitivity to infant distress and nondistress on social-emotional functioning. Child Dev. 2009, 80, 762–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradt, E.; Ablow, J. Infant physiological response to the still-face paradigm: Contributions of maternal sensitivity and infants’ early regulatory behavior. Infant Behav. Dev. 2010, 33, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, K.-A.; McMahon, C.; Reilly, N.; Austin, M.-P. Maternal sensitivity moderates the impact of prenatal anxiety disorder on infant mental development. Early Hum. Dev. 2010, 86, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, M.; Antunes, S.; Martelo, I.; Dionisio, F. The impact of low birthweight in infant patterns of regulatory behavior, mother-infant quality of interaction, and attachment. Early Hum. Dev. 2022, 172, 105633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronick, E.Z.; Gianino, A. Interactive mismatch and repair: Challenges to the coping infant. Zero Three 1986, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf, S.C.; Shapiro, J.R.; Marzolf, D. Developmental and temperamental differences in emotional regulation in infancy. Child Dev. 1995, 66, 1817–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braungart-Rieker, J.M.; Stifter, C.A. Infants’ responses to frustrating situations: Continuity and change in reactivity and regulation. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 1767–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockenberg, S.C.; Leerkes, E.M. Infant and maternal behaviors regulate infant reactivity to novelty at 6 months. Dev. Psychol. 2004, 40, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H. “It’s about time!” Ecological systems, transaction, and specificity as key developmental principles in children’s changing worlds. In Children in Changing Worlds: Sociocultural and Temporal Perspectives; Parke, R.D., Elder, G.H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 277–286. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein, M.H. Fostering optimal development and averting detrimental development: Prescriptions, proscriptions, and specificity. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2019, 23, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, R.A.; Salsberry, P.J.; Justice, L.M.; Dynia, J.M.; Logan, J.A.R.; Gugiu, M.R.; Purtell, K.M. Relations of maternal depression and parenting self-efficacy to the self-regulation of infants in low-income homes. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 2330–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radesky, J.S.; Silverstein, M.; Zuckerman, B.; Christakis, D.A. Infant self-regulation and early childhood media exposure. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e1172–e1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Depressed | Nondepressed | F/χ2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 60 | n = 60 | |||

| Mother | ||||

| Age at infant’s birth (years) | 31.72 (4.97) | 31.42 (4.21) | F(1,119) = 0.12, ns | |

| Education | 5.92 (0.90) | 6.15 (0.76) | F(1,119) = 2.34, ns | |

| Employment status (% employed) | 35.0 | 41.7 | χ2(1) = 0.56, ns | |

| Hours employed per week outside home | 13.25 (17.28) | 12.15 (16.55) | F(1,118) = 0.12, ns | |

| Ethnicity (% Non-Hispanic White) | 68.3 | 70.0 | χ2(1) = 1.74, ns | |

| Hollingshead SES | 53.63 (9.18) | 56.31 (8.42) | F(1,115) = 2.67, ns | |

| Lives with child’s biological father (%) | 95.0 | 95.0 | χ2(1) = 0.01, ns | |

| Infant | ||||

| Age (days) | 154.87 (7.40) | 153.57 (6.77) | F(1,119) = 1.01, ns | |

| Birthweight (g) | 3250.52 (443.57) | 3284.20 (517.38) | F(1,118) = 0.15, ns | |

| Gender (% female) | 35.0 | 38.3 | χ2(1) = 0.14, ns | |

| Birth order (% firstborn) | 68.3 | 50.0 | χ2(1) = 4.17, p = 0.041 | |

| Nondepressed | Depressed | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (M) | 95% CI [Lower, Upper] | Std. Error (SE) | Mean (M) | 95% CI [Lower, Upper] | Std. Error (SE) | F(1,118) | B * | p | η2 | ||

| SFP | |||||||||||

| Protest | −1.59 | [−1.88, −1.31] | 0.14 | −1.51 | [−1.79, −1.22] | 0.14 | 0.19 | −0.09 | 0.662 | 0.00 | |

| Monitor | −0.67 | [−0.82, −0.52] | 0.08 | −0.96 | [−1.11, −0.81] | 0.08 | 7.01 | 0.29 | 0.009 | 0.06 | |

| Gaze Aversion | −0.68 | [−0.81, −0.55] | 0.07 | −0.95 | [−1.08, −0.82] | 0.07 | 8.54 | 0.27 | 0.004 | 0.07 | |

| Object Attend | −0.43 | [−0.64, −0.22] | 0.11 | −0.40 | [−0.61, −0.19] | 0.11 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.828 | 0.00 | |

| Self-Soothing | −0.28 | [−0.47, −0.10] | 0.09 | −0.27 | [−0.45, −0.08] | 0.09 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.916 | 0.00 | |

| Fear Task | |||||||||||

| Fear | 0.69 | [0.50, 0.87] | 0.09 | 0.96 | [0.78, 1.15] | 0.09 | 4.29 | −0.28 | 0.040 | 0.04 | |

| Gaze Aversion | 0.64 | [0.57, 0.70] | 0.03 | 0.52 | [0.45, 0.59] | 0.03 | 5.76 | 0.12 | 0.018 | 0.05 | |

| Object Attend | 0.88 | [0.83, 0.94] | 0.03 | 0.78 | [0.73, 0.84] | 0.03 | 6.54 | 0.10 | 0.012 | 0.05 | |

| Self-Soothing | 0.28 | [0.19, 0.37] | 0.05 | 0.38 | [0.29, 0.57] | 0.05 | 2.30 | −0.09 | 0.101 | 0.01 | |

| Still-Face Paradigm (SFP) | Fear Task | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Sensitivity | Protest | Monitor | Gaze Aversion | Object Attend | Self-Soothing | Fear | Gaze Aversion | Object Attend | Self-Soothing | |

| Maternal Sensitivity | 1 | −0.09 | 0.18 * | 0.28 ** | 0.12 | 0.15 | −0.14 | 0.45 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.02 |

| Protest | 1 | −0.23 ** | −0.18 * | −0.37 ** | −0.22 * | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.09 | |

| Monitor | 1 | −0.09 | −0.22 * | 0.03 | −0.17 | 0.24 ** | 0.13 | 0.01 | ||

| Gaze Aversion | 1 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.02 | |||

| Object Attend | 1 | 0.21 * | −0.15 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.01 | ||||

| Self-Soothing | 1 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.0 | 0.01 | |||||

| Fear | 1 | −0.15 | −0.24 ** | 0.07 | ||||||

| Gaze Aversion | 1 | 0.15 | −0.01 | |||||||

| Object Attend | 1 | −0.03 | ||||||||

| Self-Soothing | 1 | |||||||||

| B | 95% CI [Lower, Upper] | Std Error (SE) | R2 Change | p | Effect Size (f2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Still-Face | |||||||

| Protest | 0.22 | (−0.790, 1.233) | 0.51 | 0.01 | 0.665 | 0.01 | |

| Monitor | 0.13 | (−1.156, −0.106) | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.572 | 0.14 | |

| Gaze Aversion | 0.63 | (−0.325, 0.587) | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.019 | 0.15 | |

| Object Attend | 0.23 | (−0.520, 0.971) | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0.551 | 0.02 | |

| Self-Soothing | 0.56 | (−0.094, 1.207) | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.093 | 0.05 | |

| Fear task | Fear | −0.23 | (−0.895, 0.434) | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.493 | 0.05 |

| Gaze Aversion | 0.27 | (0.052, 0.485) | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.016 | 0.35 | |

| Object Attend | 0.25 | (0.060, 0.437) | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.010 | 0.20 | |

| Self-Soothing | 0.11 | (−0.222, 0.434) | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.524 | 0.00 |

| Gaze Aversion | Object Attend | Self-Soothing | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | η2 | F | p | η2 | F | p | η2 | ||

| Step 1 | Context | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.952 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 1.000 | 0.00 |

| Step 1 | Depression × Context | 0.12 | 0.730 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.995 | 0.00 | 3.95 | 0.049 | 0.04 |

| Step 2 | Sensitivity × Context | 2.00 | 0.160 | 0.02 | 1.16 | 0.283 | 0.01 | 1.14 | 0.288 | 0.01 |

| Step 3 | Depression × Sensitivity × Context | 1.35 | 0.248 | 0.01 | 0.46 | 0.498 | 0.00 | 1.17 | 0.196 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manian, N.; Nyivih, S.; Manzo, V.; Adewunmi, I.; Bornstein, M.H. Effects of Maternal Depression and Sensitivity on Infant Emotion Regulation: The Role of Context. Children 2025, 12, 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101323

Manian N, Nyivih S, Manzo V, Adewunmi I, Bornstein MH. Effects of Maternal Depression and Sensitivity on Infant Emotion Regulation: The Role of Context. Children. 2025; 12(10):1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101323

Chicago/Turabian StyleManian, Nanmathi, Sandrine Nyivih, Victoria Manzo, Ibilola Adewunmi, and Marc H. Bornstein. 2025. "Effects of Maternal Depression and Sensitivity on Infant Emotion Regulation: The Role of Context" Children 12, no. 10: 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101323

APA StyleManian, N., Nyivih, S., Manzo, V., Adewunmi, I., & Bornstein, M. H. (2025). Effects of Maternal Depression and Sensitivity on Infant Emotion Regulation: The Role of Context. Children, 12(10), 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101323