Connected but at Risk: Social Media Exposure and Psychiatric and Psychological Outcomes in Youth

Abstract

Highlights

- Passive and compulsive social media use in adolescents is associated with increased risks of depression, anxiety, body dissatisfaction, and suicidal ideation.

- Neurodevelopmental vulnerabilities, gender, emotion regulation difficulties, and problematic usage patterns act as key risk factors in shaping psychiatric outcomes.

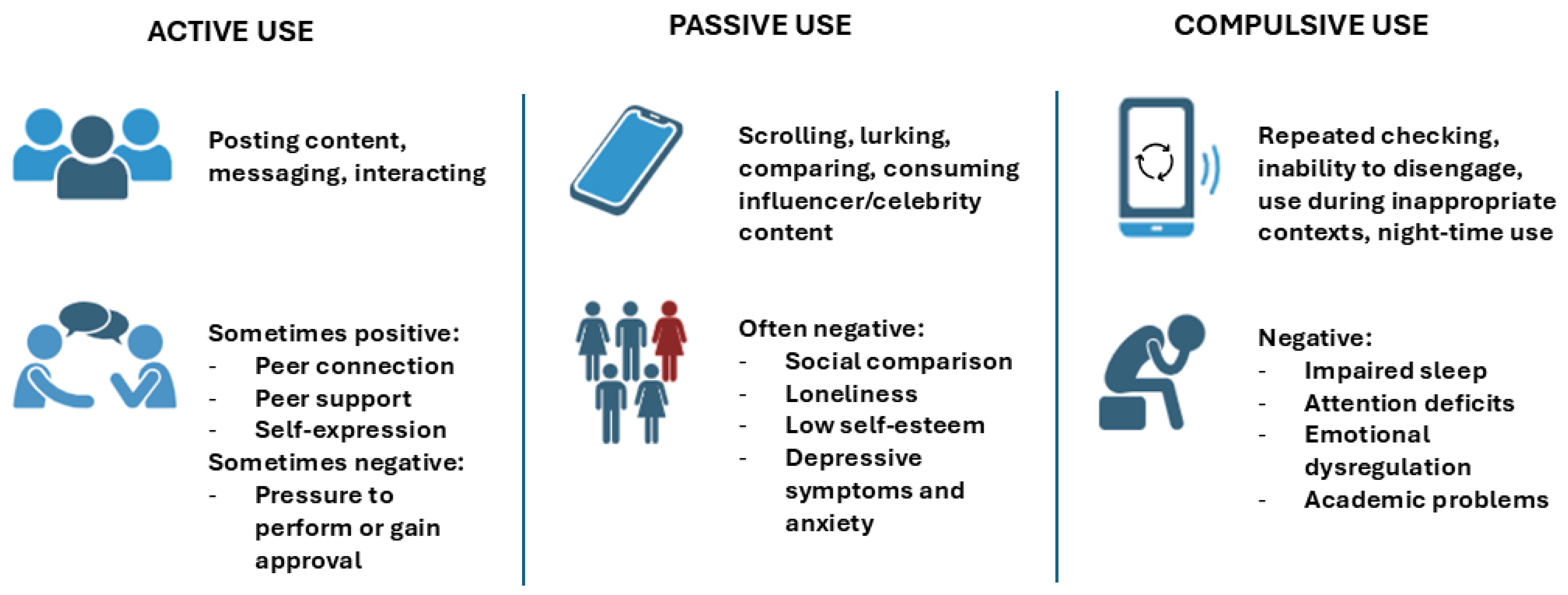

- Social media is not inherently harmful; its psychological impact depends on usage patterns, individual traits, and social context.

- Prevention strategies should go beyond limiting screen time and focus on digital literacy, family engagement, emotion regulation, and platform responsibility.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Terminology and Measurement of Technology-Use Constructs

4. Adolescent Brain Development and Vulnerability

5. Types of Social Media Use

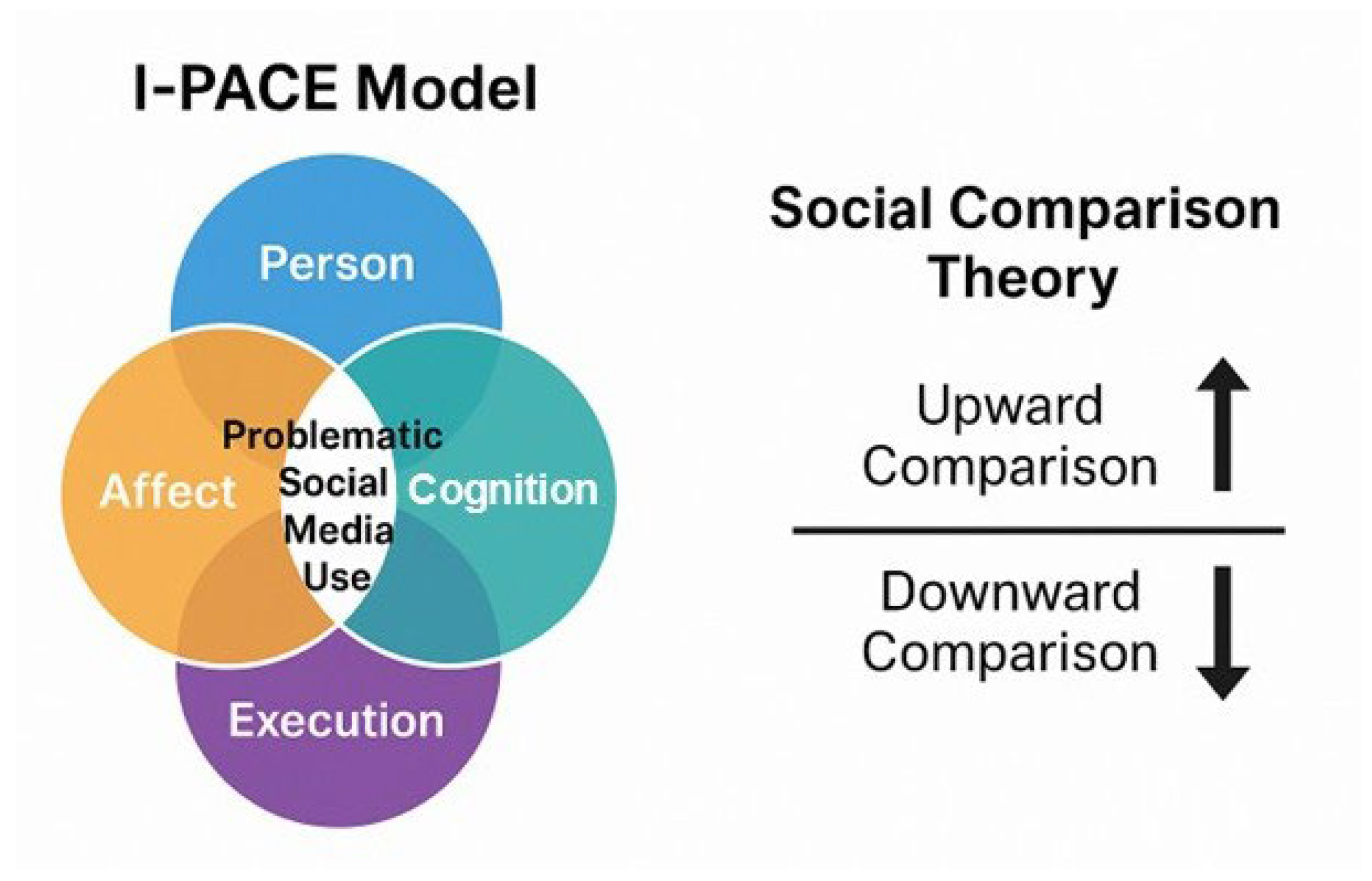

Problematic and Compulsive Use

6. Psychiatric Outcomes Associated with Social Media Use

6.1. Depression and Anxiety

6.2. Body Image Disturbance and Disordered Eating

6.3. Suicidality and Self-Harm

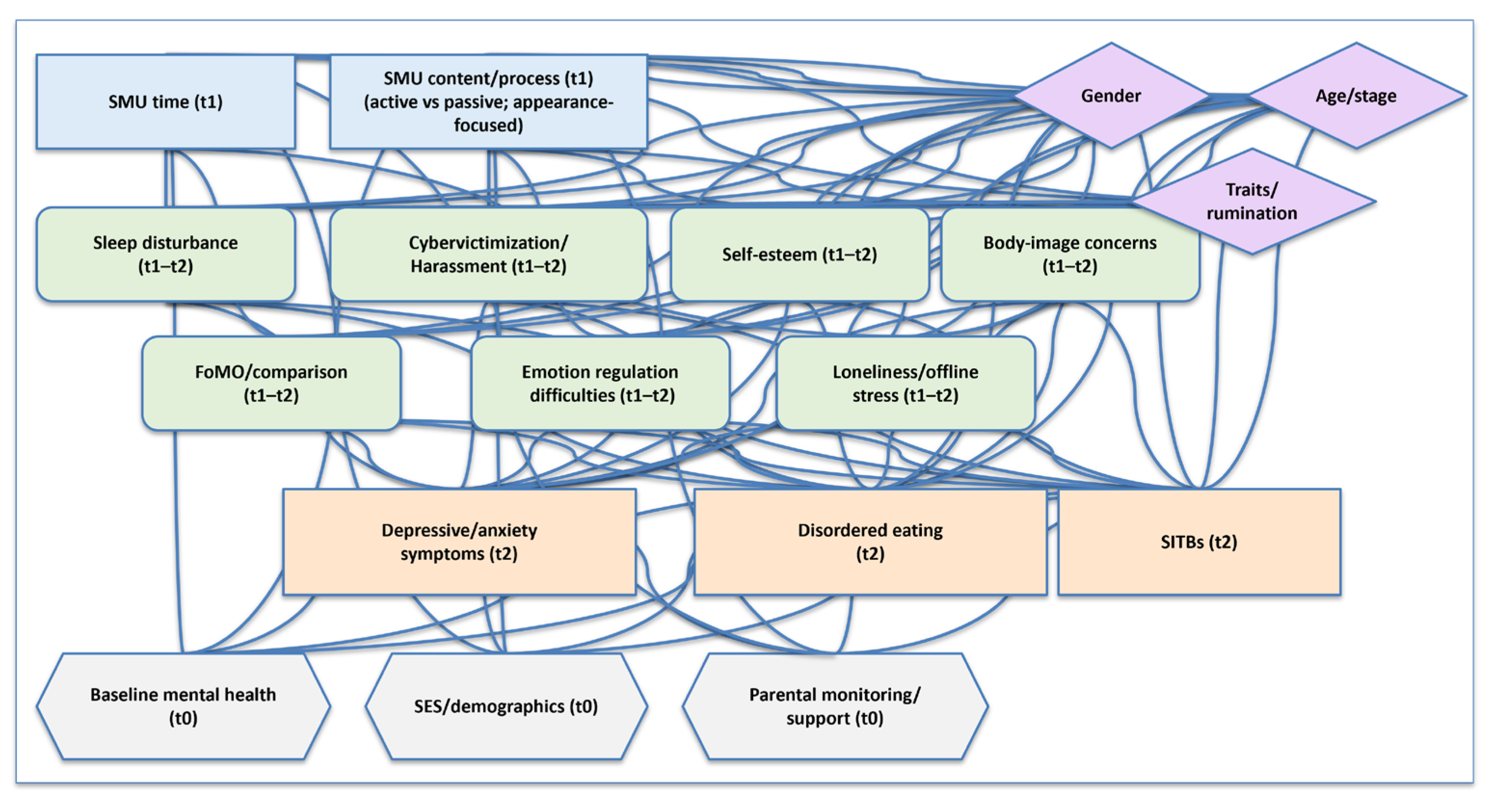

7. Moderators and Mediators of the Relationship Between Social Media Use and Mental Health

8. Implications

8.1. Beyond “Screen Time”: The Need for Precision

8.2. The Role of Families and Schools

8.3. Opportunities for Positive Engagement

8.4. Toward Evidence-Based Guidelines and Platform Responsibility

9. Discussion and Conclusions

10. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keles, B.; McCrae, N.; Grealish, A. A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Martin, G.N. Gender differences in associations between digital media use and psychological well-being: Evidence from three large datasets. J. Adolesc. 2020, 79, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesi, J.; Telzer, E.H.; Prinstein, M.J. Adolescent developmental pathways to risk for suicide: Integrating brain and behavioral science to inform prevention. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 128, 1159–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, B.J.; Jones, R.M.; Hare, T.A. The adolescent brain. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1124, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, B.; Marek, S.; Larsen, B.; Tervo-Clemmens, B.; Chahal, R. An integrative model of the maturation of cognitive control. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 38, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J.; Vartanian, L.R. Social media and body image concerns: Current research and future directions. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czubaj, N.; Szymańska, M.; Nowak, B.; Grajek, M. The Impact of Social Media on Body Image Perception in Young People. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vannucci, A.; Flannery, K.M.; Ohannessian, C.M. Social media use and anxiety in emerging adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 207, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, M.J.; Odgers, C.L. Seven fears and the science of how mobile technologies may be influencing adolescents in the digital age. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 832–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montag, C.; Walla, P. Carpe diem instead of losing your social mind: Beyond digital addiction and why we all suffer from digital overuse. Cogent Psychol. 2016, 3, 1157281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verduyn, P.; Ybarra, O.; Résibois, M.; Jonides, J.; Kross, E. Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2017, 11, 274–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.; Young, K.S.; Laier, C. Prefrontal control and internet addiction: A theoretical model and review of neuropsychological and neuroimaging findings. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzus, C.; Neubauer, A.B. Ecological Momentary Assessment: A Meta-Analysis on Designs, Samples, and Compliance Across Research Fields. Assessment 2023, 30, 825–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartanto, A.; Quek, F.Y.X.; Tng, G.Y.Q.; Yong, J.C. Does social media use increase depressive symptoms? A reverse causation perspective. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 641934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heffer, T.; Good, M.; Daly, O.; MacDonell, E.T.; Willoughby, T. The longitudinal association between social-media use and depressive symptoms among adolescents and young adults: An empirical reply to Twenge et al. (2018). Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 7, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N.Y. Psychometric properties of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale in Korean young adults. Psychiatry Investig. 2022, 19, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Boer, M.; Stevens, G.W.J.M.; Finkenauer, C.; Koning, I.M.; van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M. Validation of the Social Media Disorder Scale in adolescents: Findings from a large-scale nationally representative sample. Assessment 2022, 29, 1658–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meerkerk, G.J.; van den Eijnden, R.J.; Vermulst, A.A.; Garretsen, H.F. The Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS): Some psychometric properties. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darvesh, N.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Lachance, C.C.; Nincic, V.; Sharpe, J.P.; Ghassemi, M.; Straus, S.E.; Tricco, A.C. Exploring the prevalence of gaming disorder and Internet gaming disorder: A rapid scoping review. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meshi, D.; Morawetz, C.; Heekeren, H.R. Nucleus accumbens response to gains in reputation for the self relative to gains for others predicts social media use. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobakht, H.N.; Wichstrøm, L.; Steinsbekk, S. Longitudinal Relations Between Social Media Use and Cyberbullying Victimization Across Adolescence: Within-Person Effects in a Birth Cohort. J. Youth Adolesc. 2025. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyer, A.E.; Silk, J.S.; Nelson, E.E. The neurobiology of the emotional adolescent: From the inside out. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 70, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Crone, E.A.; Konijn, E.A. Media use and brain development during adolescence. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dong, N.; Zhou, Y.; Lei, L.; Lee, T.M.C.; Lam, C.L.M. The longitudinal impact of screen media activities on brain function, architecture and mental health in early adolescence. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2025, 25, 100589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Şimşek, O.M.; Gümüşçü, N.; Koçak, O.; Alkhulayfi, A.M.A.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Yıldırım, M. Learning and performance orientation, life satisfaction and problematic social media use in high school and university students: A moderated mediation. Acta Psychol. 2025, 258, 105224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J.; Diedrichs, P.C.; Vartanian, L.R.; Halliwell, E. Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. Body Image 2015, 13, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K. Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orben, A.; Przybylski, A.K. Screens, teens, and psychological well-being: Evidence from three time-use-diary studies. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 30, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marano, G.; Anesini, M.B.; Milintenda, M.; Acanfora, M.; Calderoni, C.; Bardi, F.; Lisci, F.M.; Brisi, C.; Traversi, G.; Mazza, O.; et al. Neuroimaging and Emotional Development in the Pediatric Population: Understanding the Link Between the Brain, Emotions, and Behavior. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonioni, F.; Mazza, M.; Autullo, G.; Pellicano, G.R.; Aceto, P.; Catalano, V.; Marano, G.; Corvino, S.; Martinelli, D.; Fiumana, V.; et al. Socio-emotional ability, temperament and coping strategies associated with different use of Internet in Internet addiction. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 3461–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; Altavilla, D.; Mazza, M.; Scappaticci, S.; Tambelli, R.; Aceto, P.; Luciani, M.; Corvino, S.; Martinelli, D.; Alimonti, F.; et al. Neural correlate of Internet use in patients undergoing psychological treatment for Internet addiction. J. Ment. Health 2017, 26, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonioni, F.; Mazza, M.; Autullo, G.; Cappelluti, R.; Catalano, V.; Marano, G.; Fiumana, V.; Moschetti, C.; Alimonti, F.; Luciani, M.; et al. Is Internet addiction a psychopathological condition distinct from pathological gambling? Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 1052–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orben, A.; Przybylski, A.K. The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2019, 3, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, A.Y.H.; Hartanto, A.; Kasturiratna, K.T.A.S.; Majeed, N.M. No consistent evidence for between- and within-person associations between objective social media screen time and body image dissatisfaction: Insights from a daily diary study. Soc. Media + Soc. 2025, 11, 20563051251313855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orben, A.; Dienlin, T.; Przybylski, A.K. Social media’s enduring effect on adolescent life satisfaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 10226–10228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, Y.; Zilanawala, A.; Booker, C.; Sacker, A. Social media use and adolescent mental health: Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. EClinicalMedicine 2019, 6, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lafontaine-Poissant, F.; Lang, J.J.; McKinnon, B.; Simard, I.; Roberts, K.C.; Wong, S.L.; Chaput, J.-P.; Janssen, I.; Boniel-Nissim, M.; Gariépy, G. Social media use and sleep health among adolescents in Canada. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2024, 44, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macrynikola, N.; Auad, E.; Menjivar, J.; Miranda, R. Does social media use confer suicide risk? A systematic review of the evidence. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2021, 3, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiphoo, A.N.; Vahedi, Z. A meta-analytic review of the relationship between social media use and body image disturbance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boers, E.; Afzali, M.H.; Newton, N.; Conrod, P. Association of screen time and depression in adolescence. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masri-Zada, T.; Martirosyan, S.; Abdou, A.; Barbar, R.; Kades, S.; Makki, H.; Haley, G.; Agrawal, D.K. The Impact of Social Media & Technology on Child and Adolescent Mental Health. J. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Disord. 2025, 9, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, W.W.Y.; Woo, B.P.Y.; Wong, C.; Yip, P.S.F. Gender differences in the relationships between meaning in life, mental health status and digital media use during Covid-19. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilby, R.; Mickelson, K.D. Combating weight-stigmatization in online spaces: The impacts of body neutral, body positive, and weight-stigmatizing TikTok content on body image and mood. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1577063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dalen, M.; Dierckx, B.; Pasmans, S.G.M.A.; Aendekerk, E.W.C.; Mathijssen, I.M.J.; Koudstaal, M.J.; Timman, R.; Williamson, H.; Hillegers, M.H.J.; Utens, E.M.W.J.; et al. Anxiety and depression in adolescents with a visible difference: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Body Image 2020, 33, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingoia, J.; Hutchinson, A.D.; Wilson, C.; Gleaves, D.H. The relationship between social networking site use and the internalization of a thin ideal in females: A meta-analytic review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, S.E.; Weinstock, M.; Vashro, T.N.; Henning, T.; Derrigo, K. Mitigating harms of social media for adolescent body image and eating disorders: A review. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 2587–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoib, S.; Chandradasa, M.; Nahidi, M.; Amanda, T.W.; Khan, S.; Saeed, F.; Swed, S.; Mazza, M.; Di Nicola, M.; Martinotti, G.; et al. Facebook and Suicidal Behaviour: User Experiences of Suicide Notes, Live-Streaming, Grieving and Preventive Strategies-A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balt, E.; Mérelle, S.; Robinson, J.; Popma, A.; Creemers, D.; van den Brand, I.; van Bergen, D.; Rasing, S.; Mulder, W.; Gilissen, R. Social media use of adolescents who died by suicide: Lessons from a psychological autopsy study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 17, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, V.; Fariña, F.; Isorna, M.; López-Roel, S.; Rolán, K. Problematic Use of the Internet and Cybervictimization: An Empirical Study with Spanish Adolescents. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S.; Griffiths, M.D. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addict. Behav. 2017, 64, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, S.M.; Rogers, A.A.; Zurcher, J.D.; Stockdale, L.; Booth, M. Does time spent using social media impact mental health?: An eight-year longitudinal study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 104, 106160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, J.; Pilkington, V.; Benakovic, R.; Wilson, M.J.; La Sala, L.; Seidler, Z. Social Media and Youth Mental Health: Scoping Review of Platform and Policy Recommendations. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e72061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odgers, C.L.; Jensen, M.R. Annual Research Review: Adolescent mental health in the digital age: Facts, fears, and future directions. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Meier, A.; Beyens, I. Social media use and well-being: What we know and what we need to know. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 45, 101294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyens, I.; Pouwels, J.L.; van Driel, I.I.; Keijsers, L.; Valkenburg, P.M. The effect of social media on well-being differs from adolescent to adolescent. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryding, F.C.; Kuss, D.J. The use of social networking sites, body image dissatisfaction, and body dysmorphic disorder: A systematic review of psychological research. Psychol. Pop. Media 2020, 9, 412–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesi, J.; Burke, T.A.; Bettis, A.H.; Kudinova, A.Y.; Liu, R.T. Social media use and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 87, 102038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, G.; Tiggemann, M. A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image 2016, 17, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhls, Y.T.; Ellison, N.B.; Subrahmanyam, K. Benefits and costs of social media in adolescence. Pediatrics 2017, 140, S67–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesi, J. The impact of social media on youth mental health: Challenges and opportunities. North Carol. Med. J. 2020, 81, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, P.; Manktelow, R.; Taylor, B. Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 41, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesi, J.; Telzer, E.H.; Prinstein, M.J. Adolescent Development in the Digital Media Context. Psychol Inq. 2020, 31, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rideout, V.; Fox, S. Digital Health Practices, Social Media Use, and Mental Well-Being Among Teens and Young Adults in the U.S. Hopelab & Well Being Trust Report. 2018. Available online: https://hopelab.org/report/a-national-survey-by-hopelab-and-well-being-trust-2018/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- McNamara, P.; Dunn, N. Netflix’s Adolescence: An unsettling reminder of the toxic effect of social media on children. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2025, 75, 320–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, C.A.; Bulgin, J.; Diaz, S.; Zhang, J.; Tan, R.; Li, L.; Armstrong-Hough, M. Communication attributes modify the anxiety risk associated with problematic social media use: Evidence from a prospective diary method study. Addict. Behav. 2025, 166, 108324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborne, A. Balancing the benefits and risks of social media on adolescent mental health in a post-pandemic world. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2025, 19, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L. Predicting Internet risks: A longitudinal panel study of gratifications-sought, Internet addiction symptoms, and social media use among children and adolescents. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2014, 2, 424–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, E.; Tomczyk, S. The Ways of Using Social Media for Health Promotion Among Adolescents: Qualitative Interview and Focus Group Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e71510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Claim/Construct | Association Type | Representative Reference(s) | Study Design/Sample | Effect-Size Metric | Point Estimate (95% CI) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital technology use vs. adolescent well-being (magnitude) | Correlational (cross-sectional; specification-curve) | Orben and Przybylski, 2019 [36] | SCA across 3 large national datasets; adolescents 12–18 y; N_tot = 355,358 Design: XS + SCA; Measure: SR; N-band: VL (≥10,000) | R2 (variance explained) | R2 ≤ 0.004 (≤0.4% of variance); CI: NR | Negative but trivially small association across specifications. |

| Daily social media use intensity and depressive symptoms (gender differences) | Association gradient; mediation paths | Kelly et al., 2019 [37] | UK Millennium Cohort Study; cross-sectional path analysis; n = 10,904; age ≈ 14 Design: XS (path); Measure: SR; N-band: VL (≥10,000) | % change in depressive symptom score (vs. 1–3 h/day reference) | Girls: 3–<5 h = +26%; ≥5 h = +50% Boys: 3–<5 h = +21%; ≥5 h = +35% Body dissatisfaction → depressive symptoms: +15% ≥5 h → body dissatisfaction: +31% more likely (CIs not reported) | Multiple pathways via sleep, online harassment, self-esteem, body image. |

| Problematic social media use and poor sleep health indicators | Adjusted odds (cross-sectional) | Lafontaine-Poissant et al., 2024 [38] | HBSC Canada 2017–2018; mixed-effects logistic models; n = 12,557 (11–17 y) Design: XS; Measure: SR; N-band: VL (≥10,000) | aOR | Problematic vs. active SMU: aORs 1.67–3.24 across 7 indicators. Examples: Insomnia symptoms aOR = 3.24 (2.61–4.02); Daytime wakefulness aOR = 2.67 (2.15–3.31); Screen time before bed aOR = 2.76 (1.86–4.08); Not meeting sleep duration recs aOR = 2.43 (2.01–2.93); Sleep variability aOR = 2.23 (1.79–2.77); Late bedtime (school days) aOR = 2.89 (2.20–3.79). | Associations stronger in girls (e.g., late bedtime: girls aOR 3.74 vs. boys 1.84; non-school days 4.13 vs. 2.18). |

| Social media use and suicidal feelings (adolescents) | Meta-analytic odds | Macrynikola et al., 2021 [39] | Systematic review/meta-analysis Design: MA/SR; Measure: SR; N-band: varies | OR | OR = 1.36 (1.10–1.67) for suicidal feelings among adolescents | Cross-sectional evidence predominates; calls for more longitudinal research. |

| Social media use and body image disturbance | Meta-analytic correlation | Saiphoo and Vahedi, 2019 [40] | Meta-analysis across published studies Design: MA/SR; Measure: SR; N-band: varies | r | r = 0.156 (95% CI 0.123–0.188) | Effects stronger for appearance-focused/photo-based use than general use; small overall magnitude. |

| Reverse causation: depressive symptoms → later SMU; SMU ↛ later depressive symptoms | Bidirectional (cross-lagged panel) | Heffer et al., 2019 [16] | Adolescents (n = 597; 2 waves) and young adults (n = 1132; 6 waves) Design: CLP; Measure: SR; N-band: M–L (≈600 and 1132) | Standardized β (cross-lag) | Adolescent females: Dep1 → SM2 β = 0.131 (0.026–0.236); SM1 → Dep2 β = −0.043 (−0.159–0.073), ns. Adolescent males: SM1 → Dep2 β = 0.145 (0.000–0.288), p ≈ 0.051 (ns with covariates); Dep1 → SM2 β = 0.094 (−0.033–0.220), ns. | Supports depressive symptoms predicting later SMU in girls; minimal evidence for SMU → later depression. |

| Type | Factor | Operationalization/Example Measure | Expected Direction (Summary) | Study Design/Measure | Representative Evidence | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator | Sleep disturbance | Sleep duration/quality; insomnia symptoms; bedtime variability | Higher SMU → poorer sleep → higher depressive/anxiety symptoms | L; SR (some OBJ time) | Kelly et al., 2019 [37] | Gender-differentiated pathways reported in UK cohort; also supported by reviews. |

| Mediator | Cybervictimization/online harassment | Self-report frequency in past 6–12 months | Higher SMU → ↑ cybervictimization → ↑ depressive/suicidal symptoms | L/XS; SR | Kelly et al., 2019 [37]; Macrynikola et al., 2021 [39] | Often co-occurs with offline bullying; temporality clearer in cohorts. |

| Mediator | Self-esteem | Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale | Higher SMU (esp. passive/appearance-focused) → ↓ self-esteem → ↑ depressive symptoms | L/XS; SR | Kelly et al., 2019 [37]; Saiphoo and Vahedi, 2019 [40] | Effects small on average; content/process specificity matters. |

| Mediator | Body image concerns | SATAQ; body dissatisfaction scales | Appearance-focused activities → ↑ body concern → ↑ disordered eating/depression | MA/XS; SR | Saiphoo and Vahedi, 2019 [40]; Holland et al., 2016 [59] | Larger effects for photo-based SNS; heterogeneity across measures. |

| Mediator | Emotion regulation difficulties | DERS; dysregulation indices | Problematic/compulsive use → ↑ emotion dysregulation → ↑ symptoms | XS/L; SR | Heffer et al., 2019 [16] | Directionality mixed; see CLP evidence for reverse paths as well. |

| Mediator | FoMO/upward social comparison | FoMO scale; comparison orientation scales | Passive/scrolling/photo activities → ↑ FoMO/comparison → ↑ distress | XS/DD; SR | Holland et al., 2016 [59]; Orben et al., 2019 [36] | Mechanistic plausibility; average effects small. |

| Mediator | Loneliness/offline stress | UCLA loneliness; life event checklists | SMU under stress → ↑ loneliness/stress → ↑ symptoms | L/XS; SR | Boers et al., 2019 [41] | Time-varying confounding possible; consider within-person designs. |

| Moderator | Gender | Male/female; gender identity where available | Stronger associations for girls in several outcomes (sleep, body image, depression) | L/XS; SR | Kelly et al., 2019 [37]; Lafontaine-Poissant et al., 2024 [38] | See sleep health and body-image pathways; not universal across outcomes. |

| Moderator | Developmental stage/age | Early vs. mid vs. late adolescence | Effects vary by age; mid-adolescence often more sensitive | L/XS; SR | Kelly et al., 2019 [37] | Developmental transitions and peer salience may amplify effects. |

| Moderator | Baseline mental health/vulnerability | Baseline depression/anxiety; clinical subgroup | Higher baseline symptoms → stronger SMU–outcome associations | CLP/L; SR | Heffer et al., 2019 [16]; Hartanto et al., 2021 [15] | Reverse-causation pathway: symptoms → later problematic SMU. |

| Moderator | Personality traits (e.g., neuroticism)/rumination | BFI/EPQ; RRS rumination scale | Higher neuroticism/rumination → stronger adverse associations | XS; SR | Odgers and Jensen, 2020 [54] | Theoretical synthesis; empirical evidence heterogeneous. |

| Moderator | Active vs. passive use | Posting/messaging vs. browsing/scrolling ratios | Passive use often linked to worse mood; active engagement less so | XS/DD; SR/OBJ | Valkenburg et al., 2022 [55]; Beyens et al., 2020 [56] | Within-person effects small/variable; content still key. |

| Moderator | Platform/content type (photo-based) | Instagram/photo-centric vs. text-centric activities | Photo-based use → stronger body-image links | MA/XS; SR | Saiphoo and Vahedi, 2019 [40]; Ryding and Kuss, 2020 [57] | Appearance-focused content amplifies risk pathways. |

| Moderator | Parental monitoring/offline support | Parenting practices; perceived support | Higher monitoring/support → weaker adverse associations (buffer) | XS/L; SR | Nesi et al., 2021 [58] | Buffering effects vary; more causal evidence needed. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marano, G.; Lisci, F.M.; Rossi, S.; Marzo, E.M.; Boggio, G.; Brisi, C.; Traversi, G.; Mazza, O.; Pola, R.; Gaetani, E.; et al. Connected but at Risk: Social Media Exposure and Psychiatric and Psychological Outcomes in Youth. Children 2025, 12, 1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101322

Marano G, Lisci FM, Rossi S, Marzo EM, Boggio G, Brisi C, Traversi G, Mazza O, Pola R, Gaetani E, et al. Connected but at Risk: Social Media Exposure and Psychiatric and Psychological Outcomes in Youth. Children. 2025; 12(10):1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101322

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarano, Giuseppe, Francesco Maria Lisci, Sara Rossi, Ester Maria Marzo, Gianluca Boggio, Caterina Brisi, Gianandrea Traversi, Osvaldo Mazza, Roberto Pola, Eleonora Gaetani, and et al. 2025. "Connected but at Risk: Social Media Exposure and Psychiatric and Psychological Outcomes in Youth" Children 12, no. 10: 1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101322

APA StyleMarano, G., Lisci, F. M., Rossi, S., Marzo, E. M., Boggio, G., Brisi, C., Traversi, G., Mazza, O., Pola, R., Gaetani, E., & Mazza, M. (2025). Connected but at Risk: Social Media Exposure and Psychiatric and Psychological Outcomes in Youth. Children, 12(10), 1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101322