Adolescents with Persistent Symptoms Following Acute SARS-CoV-2 Infection (Long-COVID): Symptom Profile, Clustering and Follow-Up Symptom Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of Adolescent Patients Accessing Care for Long-COVID

3.2. Complications Related to Acute SARS-CoV-2 Infection

3.3. Profile of Symptoms Reported and Variables Associated with Symptoms

3.4. Clustering of Cases

3.5. Diagnostic Tests

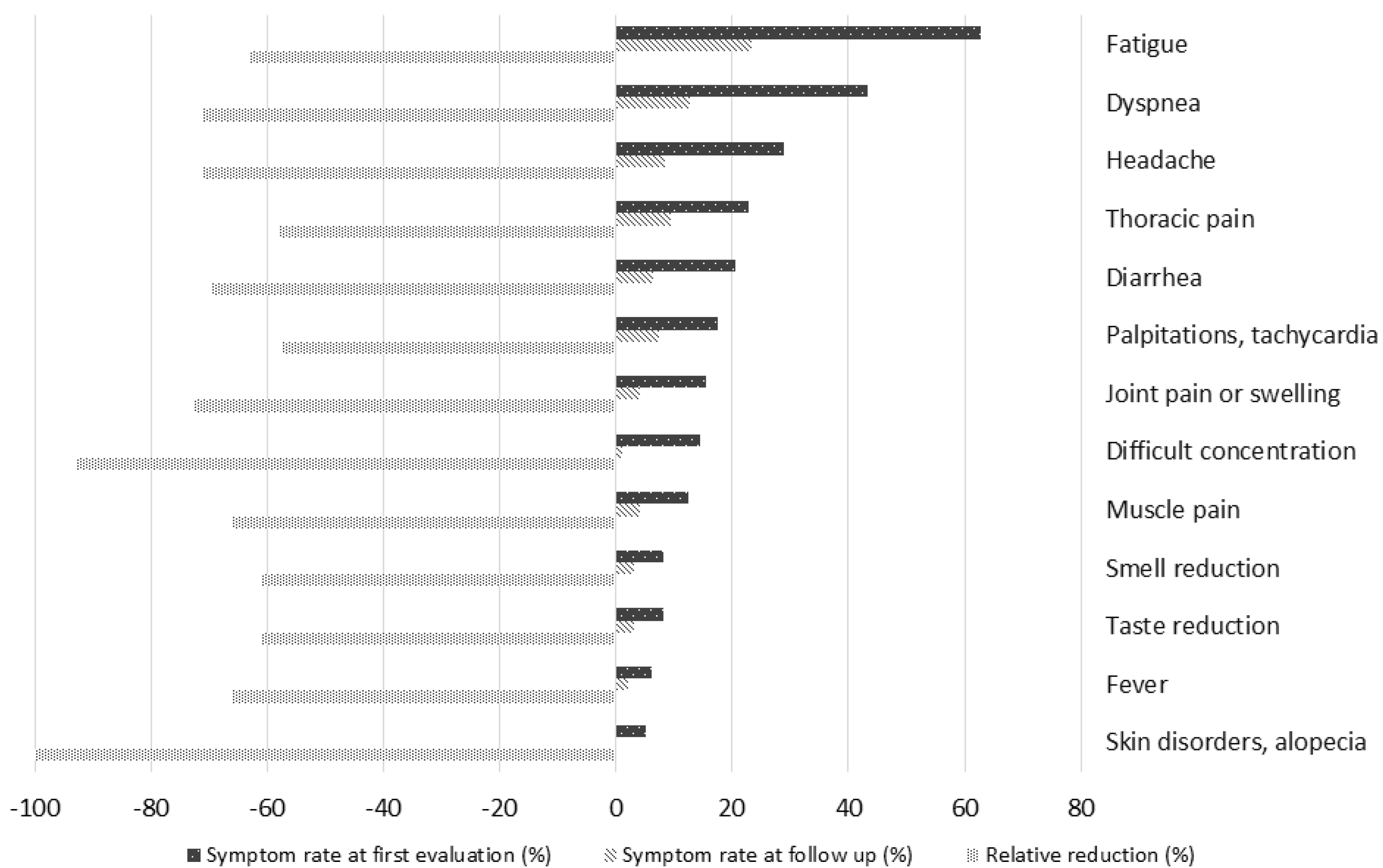

3.6. Symptom Persistence During Follow Up

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). COVID-19 Epidemiological Update. Edition 167, 17 May 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-epidemiological-update-edition-167 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Ramos, S.C.; Maldonado, J.E.; Vandeplas, A.; Ványolós, I. European Commission Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. Long COVID: A Tentative Assessment of Its Impact on Labour Market Participation and Potential Economic Effects in the EU. Available online: https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/publications/long-covid-tentative-assessment-its-impact-labour-market-participation-and-potential-economic_en (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Prevalence of Post COVID-19 Condition Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Study Data, Stratified by Recruitment Setting. 27 October 2022. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Prevalence-post-COVID-19-condition-symptoms.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE Guideline, No. 188, 2020 Dec 18: COVID-19 Rapid Gguideline: Managing the Long-Term Effects of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188 (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC). Long COVID or Post-COVID Conditions. Updated 14 March 2024. Available online: https://www.covid.gov/be-informed/longcovid/about#term (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Post COVID-19 Condition (Long COVID). 7 December 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO). A Clinical Case Definition for Post COVID-19 Condition in Children and Adolescents by Expert Consensus, 16 February 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post-COVID-19-condition-CA-Clinical-case-definition-2023-1 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Rao, S.; Gross, R.S.; Mohandas, S.; Stein, C.R.; Case, A.; Dreyer, B.; Pajor, N.M.; Bunnell, H.T.; Warburton, D.; Berg, E.; et al. Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 in Children. Pediatrics 2024, 153, e2023062570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiavo, M.; Di Filippo, P.; Porreca, A.; Prezioso, G.; Orlandi, G.; Rossi, N.; Chiarelli, F.; Attanasi, M. Potential Predictors of Long COVID in Italian Children: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Children 2024, 11, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, R.; Sonnappa, S.; Goddings, A.-L.; Whittaker, E.; Segal, T.Y. A review of post COVID syndrome pathophysiology, clinical presentation and management in children and young people. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behnood, S.; Newlands, F.; O’mahoney, L.; Ghahfarokhi, M.H.; Muhid, M.Z.; Dudley, J.; Stephenson, T.; Ladhani, S.N.; Bennett, S.; Viner, R.M.; et al. Persistent symptoms are associated with long term effects of COVID-19 among children and young people: Results from a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0293600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, R.; Chiappini, E.; Licari, A.; Galli, L.; Marseglia, G.L. Prevalence and clinical presentation of long COVID in children: A systematic review. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 3995–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toepfner, N.; Brinkmann, F.; Augustin, S.; Stojanov, S.; Behrends, U. Long COVID in pediatrics—epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2024, 183, 1543–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahratian, A.; Adjaye-Gbewonyo, D.; Lin, J.M.S.; Saydah, S. Long COVID in Children: United States, 2022. NCHS Data Brief 2023, 479, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Kuang, T.; Liu, X. Advances in researches on long coronavirus disease in children: A narrative review. Transl. Pediatr. 2024, 13, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, A.H.; Nurchis, M.C.; Garlasco, J.; Mara, A.; Pascucci, D.; Damiani, G.; Gianino, M.M. Pediatric post COVID-19 condition: An umbrella review of the most common symptoms and associated factors. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Romieu-Hernandez, A.; Boehmer, T.K.; Azziz-Baumgartner, E.; Carton, T.W.; Gundlapalli, A.V.; Fearrington, J.; Nagavedu, K.; Dea, K.; Moyneur, E.; et al. Association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and select symptoms and conditions 31 to 150 days after testing among children and adults. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridia, M.; Grassi, T.; Giuliano, M.; Tiple, D.; Pricci, F.; Villa, M.; Silenzi, A.; Onder, G. Characteristics of Long-COVID Care Centers in Italy. A National Survey of 124 Clinical Sites. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 975527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post COVID-19 CRF from the WHO Global Clinical Platform for COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global-covid-19-clinical-platform-case-report-form-(crf)-for-post-covid-conditions-(post-covid-19-crf-) (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Castriotta, L.; Onder, G.; Rosolen, V.; Beorchia, Y.; Fanizza, C.; Bellini, B.; Floridia, M.; Giuliano, M.; Silenzi, A.; Pricci, F.; et al. Examining potential Long COVID effects through utilization of healthcare resources: A retrospective, population-based, matched cohort study comparing individuals with and without prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floridia, M.; Giuliano, M.; Weimer, L.E.; Ciardi, M.R.; Agostoni, P.; Palange, P.; Querini, P.R.; Zucco, S.; Tosato, M.; Forte, A.L.; et al. Symptom profile, case and symptom clustering, clinical and demographic characteristics of a multicentre cohort of 1297 patients evaluated for Long-COVID. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.Y.B.; Morrow, A.K.; Malone, L.A. Exploring the Influence of Pre-Existing Conditions and Infection Factors on Pediatric Long COVID Symptoms and Quality of Life. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 103, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seylanova, N.; Chernyavskaya, A.; Degtyareva, N.; Mursalova, A.; Ajam, A.; Xiao, L.; Aktulaeva, K.; Roshchin, P.; Bobkova, P.; Aiyegbusi, O.L.; et al. Core outcome measurement set for research and clinical practice in post-COVID-19 condition (long COVID) in children and young people: An international Delphi consensus study “PC-COS Children”. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 63, 2301761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Almeida, F.J.; Baillie, J.K.; Bowen, A.C.; Britton, P.N.; Brizuela, M.E.; Buonsenso, D.; Burgner, D.; Chew, K.Y.; Chokephaibulkit, K.; et al. International Pediatric COVID-19 Severity Over the Course of the Pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2023, 177, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noij, L.C.E.; Blankestijn, J.M.; Lap, C.R.; van Houten, M.A.; Biesbroek, G.; der Zee, A.-H.M.-V.; Abdel-Aziz, M.I.; van Goudoever, J.B.; Alsem, M.W.; Brackel, C.L.H.; et al. Clinical-based phenotypes in children with pediatric post-COVID-19 condition. World J. Pediatr. 2024, 20, 682–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weakley, K.E.M.; Schikler, A.M.; Green, J.V.; Blatt, D.B.; Barton, S.M.M.; Statler, V.A.M.; Feygin, Y.; Marshall, G.S. Clinical Features and Follow-up of Referred Children and Young People with Long COVID. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2023, 42, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios, S.; Krivchenia, K.; Eisner, M.; Young, B.; Ramilo, O.; Mejias, A.; Lee, S.; Kopp, B.T. Long-term pulmonary sequelae in adolescents post-SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2022, 57, 2455–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonsenso, D.; Morello, R.; De Rose, C.; Spera, F.; Baldi, F. Long-term outcome of a child with postcovid condition: Role of cardiopulmonary exercise testing and 24-h Holter ECG to monitor treatment response and recovery. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2023, 58, 2944–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonsenso, D.; Camporesi, A.; Morello, R.; De Rose, C.; Fracasso, M.; Valentini, P. Paediatric long COVID studies should focus on clinical evaluations that examine the impact on daily life not just self-reported symptoms. Acta Paediatr. 2024, 113, 778–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutfreund, M.C.; Kobayashi, T.; Callado, G.Y.; Pardo, I.; Hsieh, M.K.; Lin, V.; Perencevich, E.N.; Salinas, J.L.; Edmond, M.B.; Mendonça, E.; et al. The effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines in the prevention of post-COVID conditions in children and adolescents: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob. Steward. Health Epidemiol. 2024, 4, e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, M.A.; Rosca, D.; Bratosin, F.; Fira-Mladinescu, O.; Ilie, A.C.; Burtic, S.-R.; Fildan, A.P.; Fizedean, C.M.; Jianu, A.M.; Negrean, R.A.; et al. Impact of Pre-Infection COVID-19 Vaccination on the Incidence and Severity of Post-COVID Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2024, 12, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaghi, H.; Forrest, C.B.; Hirabayashi, K.; Wu, Q.; Allen, A.J.; Rao, S.; Chen, Y.; Bunnell, H.T.; Chrischilles, E.A.; Cowell, L.G.; et al. Vaccine Effectiveness Against Long COVID in Children. Pediatrics 2024, 153, e2023064446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All | Female | Male | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex: (n, %) | 97 (100%) | 53 (54.6%) | 44 (45.4%) | |

| Age (years, mean, SD) | 13.5 (1.5) | 13.4 (1.5) | 13.6 (1.6) | 0.502 |

| Comorbidities (n, %) | 8 (8.2%) | 4 (7.5%) | 4 (9.1%) | 0.783 |

| Asthma | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| Tourette syndrome, anxiety | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Obesity, pituitary hypoplasia, metabolic syndrome, anxiety | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Hashimoto thyroiditis | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Epilepsy | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Trisomy 21 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Vaccinated before infection * | 40 (43.0%) | 21 (42.0%) | 19 (44.2%) | 0.832 |

| Not vaccinated | 53 (57.0%) | 29 (58.0%) | 24 (55.8%) | |

| Acute infection pandemic phase: Pre-Omicron | 46 (47.4%) | 25 (47.2%) | 21 (47.7%) | 0.956 |

| Omicron | 51 (52.6%) | 28 (52.8%) | 23 (52.3%) | |

| Hospitalised during acute phase (n: 96): | 3 (3.1%) | 1 (1.9%) | 2 (4.5%) | 0.462 |

| Admitted to intensive care unit: | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| WHO COVID severity grade: Mild | 88 (90.7%) | 49 (92.5%) | 39 (88.6%) | 0.482 |

| Moderate | 7 (7.2%) | 3 (5.7%) | 4 (9.1%) | |

| Severe | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.3%) | |

| Critical | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unknown | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Respiratory assistance: None | 96 (99.0%) | 52 (98.1%) | 44 (100%) | 0.360 |

| Unknown | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) |

| Phase of Pandemic | Comorbidities | Severity of Acute Disease | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n: 97) | Omicron (n: 51) | Pre-Omicron (n: 46) | p Value | Yes (n: 8) | No (n: 89) | p Value | Mild (n: 88) | Moderate/Severe (n: 8) | p Value | |

| Fatigue (n, %) | 61 (62.9%) | 37 (72.5) | 24 (52.2) | 0.038 | 2 (25.0) | 59 (66.3) | 0.049 | 54 (61.4) | 6 (75.0) | 0.706 |

| Dyspnea (n, %) | 42 (43.3%) | 18 (35.3) | 24 (52.2) | 0.094 | 4 (50.0) | 38 (42.7) | 0.724 | 37 (42.0) | 5 (62.5) | 0.292 |

| Headache (n, %) | 28 (28.9%) | 16 (31.4) | 12 (26.1) | 0.566 | 2 (25.0) | 26 (29.2) | 1.000 | 25 (28.4) | 3 (37.5) | 0.688 |

| Thoracic pain (n, %) | 22 (22.7%) | 8 (15.7) | 14 (30.4) | 0.083 | 5 (62.5) | 17 (19.1) | 0.014 | 17 (19.3) | 4 (50.0) | 0.066 |

| Diarrhea (n, %) | 20 (20.6%) | 8 (15.7) | 12 (26.1) | 0.206 | 1 (12.5) | 19 (21.3) | 1.000 | 19 (21.6) | 1 (12.5) | 1.000 |

| Palpitations, tachycardia (n, %) | 17 (17.5%) | 8 (15.7) | 9 (19.6) | 0.616 | 1 (12.5) | 16 (18.0) | 1.000 | 13 (14.8) | 4 (50.0) | 0.031 |

| Joint pain or swelling (n, %) | 15 (15.5%) | 7 (13.7) | 8 17.4) | 0.618 | 1 (12.5) | 14 (15.7) | 1.000 | 12 (13.6) | 3 (37.5) | 0.107 |

| Difficult concentration (n, %) | 14 (14.4%) | 6 (11.8) | 8 (17.4) | 0.431 | 1 (12.5) | 13 (14.6) | 1.000 | 13 (14.8) | 1 (12.5) | 1.000 |

| Muscle pain (n, %) | 12 (12.4%) | 5 (9.8) | 7 (15.2) | 0.419 | 0 (0) | 12 (13.5) | 0.590 | 9 (10.2) | 3 (37.5) | 0.059 |

| Taste reduction (n, %) | 8 (8.2%) | 2 (3.9) | 6 (13.0) | 0.145 | 0 (0) | 8 (9.0) | 1.000 | 8 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Smell reduction (n, %) | 8 (8.2%) | 2 (3.9) | 6 (13.0) | 0.145 | 1 (12.5) | 7 (7.9) | 0.511 | 8 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Fever (n, %) | 6 (6.2%) | 1 (2.2) | 5 (9.8) | 0.208 | 1 (12.5) | 5 (5.6) | 0.412 | 4 (4.5) | 2 (25.0) | 0.077 |

| Skin disorders, alopecia (n, %) | 5 (5.2%) | 3 (5.9) | 2 (4.3) | 1.000 | 1 (12.5) | 4 (4.5) | 0.356 | 5 (5.7) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (96) | 64 | 32 | |

| Female (n, %) | 38 (59.4) | 14 (43.8) | 0.148 |

| Omicron phase of the pandemic (n, %) | 22 (34.4) | 28 (87.5) | <0.001 |

| Presence of comorbidities (n, %) | 5 (7.8) | 3 (9.4) | 1.000 |

| Acute infection moderate or severe (n, %) | 7 (10.9) | 1 (3.1) | 0.262 |

| Number of symptoms reported (mean, SD) | 3.5 (1.8) | 1.5 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Fatigue (n, %) | 38 (59.4) | 22 (68.8) | 0.371 |

| Dyspnea (n, %) | 42 (65.6) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Headache (n, %) | 16 (25.0) | 12 (37.5) | 0.204 |

| Thoracic pain (n, %) | 18 (28.1) | 3 (9.4) | 0.040 |

| Diarrhea (n, %) | 19 (29.7) | 1 (3.1) | 0.003 |

| Palpitations, tachycardia (n, %) | 15 (23.4) | 2 (6.3) | 0.047 |

| Joint pain or swelling (n, %) | 15 (23.4) | 0 (0) | 0.002 |

| Difficult concentration (n, %) | 13 (20.3) | 1 (3.1) | 0.030 |

| Muscle pain (n, %) | 12 (18.8) | 0 (0) | 0.007 |

| Taste reduction (n, %) | 8 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 0.049 |

| Smell reduction (n, %) | 8 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 0.049 |

| Fever (n, %) | 2 (3.1) | 4 (12.5) | 0.093 |

| Skin disorders, alopecia (n, %) | 4 (6.3) | 1 (3.1) | 0.662 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Floridia, M.; Buonsenso, D.; Macculi, L.; Weimer, L.E.; Giuliano, M.; Pricci, F.; Bianchi, L.; Toraldo, D.M.; Onder, G.; The ISS Long-COVID Study Group. Adolescents with Persistent Symptoms Following Acute SARS-CoV-2 Infection (Long-COVID): Symptom Profile, Clustering and Follow-Up Symptom Evaluation. Children 2025, 12, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12010028

Floridia M, Buonsenso D, Macculi L, Weimer LE, Giuliano M, Pricci F, Bianchi L, Toraldo DM, Onder G, The ISS Long-COVID Study Group. Adolescents with Persistent Symptoms Following Acute SARS-CoV-2 Infection (Long-COVID): Symptom Profile, Clustering and Follow-Up Symptom Evaluation. Children. 2025; 12(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleFloridia, Marco, Danilo Buonsenso, Laura Macculi, Liliana Elena Weimer, Marina Giuliano, Flavia Pricci, Leila Bianchi, Domenico Maurizio Toraldo, Graziano Onder, and The ISS Long-COVID Study Group. 2025. "Adolescents with Persistent Symptoms Following Acute SARS-CoV-2 Infection (Long-COVID): Symptom Profile, Clustering and Follow-Up Symptom Evaluation" Children 12, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12010028

APA StyleFloridia, M., Buonsenso, D., Macculi, L., Weimer, L. E., Giuliano, M., Pricci, F., Bianchi, L., Toraldo, D. M., Onder, G., & The ISS Long-COVID Study Group. (2025). Adolescents with Persistent Symptoms Following Acute SARS-CoV-2 Infection (Long-COVID): Symptom Profile, Clustering and Follow-Up Symptom Evaluation. Children, 12(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12010028