Relationships Among Soda and Energy Drink Consumption, Substance Use, Mental Health and Risk-Taking Behavior in Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

2.2. Analytic Plan

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Relationship Among Soda Consumption and Substance Use Behaviors

3.3. Relationship Among ED Consumption and Substance Use Behaviors

3.4. Relationship Among Soda and ED Consumption and Violent Behaviors

3.5. Relationship Among Soda and ED Consumption and Mental Health Outcomes

3.6. Relationship Among Soda and ED Consumption and Lifestyle Behaviors

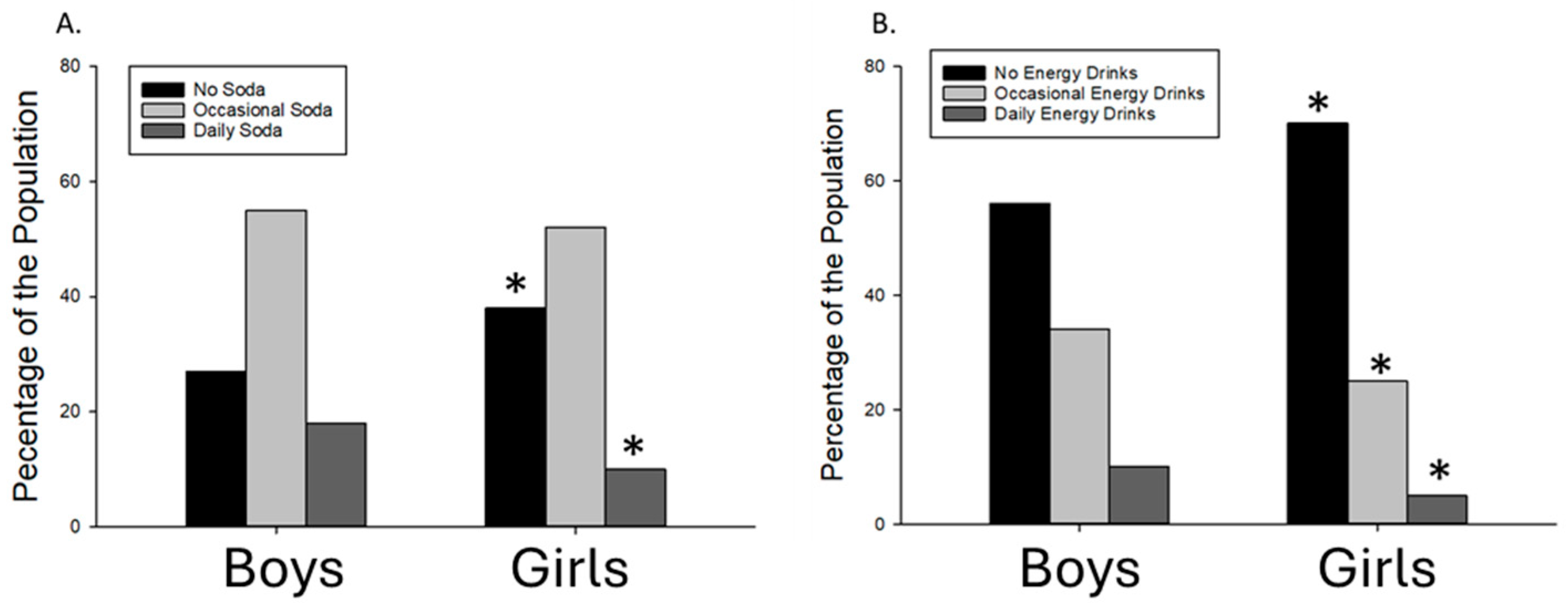

3.7. Sex Differences in Soda and ED Consumption and the Relationships with Other Behaviors

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frary, C.D.; Johnson, R.K.; Wang, M.Q. Food sources and intakes of caffeine in the diets of persons in the United States. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2005, 105, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, D.C.; Knight, C.A.; Hockenberry, J.; Teplansky, R.; Hartman, T.J. Beverage caffeine intakes in the U.S. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 63, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verster, J.C.; Koenig, J. Caffeine intake and its sources: A review of national representative studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1250–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLellan, T.M.; Caldwell, J.A.; Lieberman, H.R. A review of caffeine’s effects on cognitive, physical and occupational performance. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 71, 294–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saimaiti, A.; Zhou, D.D.; Li, J.; Xiong, R.G.; Gan, R.Y.; Huang, S.Y.; Shang, A.; Zhao, C.N.; Li, H.Y.; Li, H.B. Dietary sources, health benefits, and risks of caffeine. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 9648–9666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J.L. Review: Trends, Safety, and Recommendations for Caffeine Use in Children and Adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 58, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J.L.; Bernard, C.; Lipshultz, S.E.; Czachor, J.D.; Westphal, J.A.; Mestre, M.A. The Safety of Ingested Caffeine: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soos, R.; Gyebrovszki, A.; Toth, A.; Jeges, S.; Wilhelm, M. Effects of Caffeine and Caffeinated Beverages in Children, Adolescents and Young Adults: Short Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, C.P.; Bright, D. Caffeine consumption and weekly sleep patterns in US seventh-, eighth-, and ninth-graders. Pediatrics 2003, 111, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G.; Smith, A.P. Breakfast and Energy Drink Consumption in Secondary School Children: Breakfast Omission, in Isolation or in Combination with Frequent Energy Drink Use, is Associated with Stress, Anxiety, and Depression Cross-Sectionally, but not at 6-Month Follow-Up. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, N.; Herrick, K.; Moshfegh, A.; Rybak, M. Caffeine intake in children in the United States and 10-y trends: 2001–2010. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 1124–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branum, A.M.; Rossen, L.M.; Schoendorf, K.C. Trends in caffeine intake among U.S. children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2014, 133, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercammen, K.A.; Koma, J.W.; Bleich, S.N. Trends in Energy Drink Consumption Among U.S. Adolescents and Adults, 2003–2016. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, N.L.; Barraj, L.M.; Bi, X.; Jack, M.M. Trends and patterns of caffeine consumption among US teenagers and young adults, NHANES 2003–2012. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 94, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brice, C.F.; Smith, A.P. Factors associated with caffeine consumption. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2002, 53, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Penolazzi, B.; Natale, V.; Leone, L.; Russo, P.M. Individual differences affecting caffeine intake. Analysis of consumption behaviours for different times of day and caffeine sources. Appetite 2012, 58, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.E. Energy drinks, race, and problem behaviors among college students. J. Adolesc. Health 2008, 43, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.E. Wired: Energy drinks, jock identity, masculine norms, and risk taking. J. Am. Coll. Health 2008, 56, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinoi, M.; Paripinel, M.; Gasparini, A.; Ferraroni, M.; Edefnoti, V. Risk behaviors, substance use, and other lifestlye correlated of energy drink consumption in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 141, 1307–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.M.; Temple, J.L. Soda Consumption is Associated with Risk-Taking Behaviors in Adolescents. Am. J. Health Behav. 2015, 39, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brener, N.D.; Kann, L.; Kinchen, S.A.; Grunbaum, J.A.; Whalen, L.; Eaton, D.; Hawkins, J.; Ross, J.G. Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2004, 53, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Colder, C.R.; Campbell, R.T.; Ruel, E.; Richardson, J.L.; Flay, B.R. A finite mixture model of growth trajectories of adolescent alcohol use: Predictors and consequences. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 70, 976–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, D.K.; Olsen, E.O.; Brener, N.D.; Scanlon, K.S.; Kim, S.A.; Demissie, Z.; Yaroch, A.L. A comparison of fruit and vegetable intake estimates from three survey question sets to estimates from 24-hour dietary recall interviews. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, C.K.; Prichard, J.R. Demographics, Health, and Risk Behaviors of Young Adults Who Drink Energy Drinks and Coffee Beverages. J. Caffeine Res. 2016, 6, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, N.; Dewolfe, J.; Story, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Adolescent consumption of sports and energy drinks: Linkages to higher physical activity, unhealthy beverage patterns, cigarette smoking, and screen media use. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2014, 46, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalese, M.; Denoth, F.; Siciliano, V.; Bastini, L.; Cotichini, R.; Cutilli, A.; Molinaro, S. Energy Drink and Alcohol mixed Energy Drink use among high school adolescents: Association with risk taking behavior, social characteristics. Addict. Behav. 2017, 72, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry-McElrath, Y.M.; O’Malley, P.M.; Johnston, L.D. Energy drinks, soft drinks, and substance use among United States secondary school students. J. Addict. Med. 2014, 8, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjansson, A.L.; Kogan, S.M.; James, J.E.; Sigfusditti, I.D. Adolescent caffeine consumption and aggressive behavior: A longitudinal study. Subst. Abus. 2021, 42, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulkerson, J.A.; Sherwood, N.E.; Perry, C.L.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Story, M. Depressive symptoms and adolescent eating and health behaviors: A multifaceted view in a population-based sample. Prev. Med. 2004, 38, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utter, J.; Denny, S.; Teevale, T.; Sheridan, J. Energy drink consumption among New Zealand adolescents: Associations with mental health, health risk behaviors and body size. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2018, 54, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, E.J.; Banks, S.; Coates, A.M.; Kohler, M.J. The Relationship Between Caffeine, Sleep, and Behavior in Children. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orbeta, R.L.; Overpeck, M.D.; Ramcharran, D.; Kogan, M.D.; Ledsky, R. High caffeine intake in adolescents: Associations with difficulty sleeping and feeling tired in the morning. J. Adolesc. Health 2006, 38, 451–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapp, G.S.; Hurworth, M.; Jacoby, P.; Maddison, K.; Allen, K.; Christian, H.; Ambrosini, G.L.; Oddy, W.; Eastwood, P.R. Energy drink intake is associated with insomnia and decreased daytime functioning in young adult females. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 1328–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almulla, A.A.; Faris, M.A.E. Energy drinks consumption is assocaited with reduced sleep duration and increased energy-dense fast foods consuption among school students: A cross-sectional study. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2020, 32, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, J. Consumption of nutritional supplements among adolescents: Usage and perceived benefits. Health Educ. Res. 2003, 18, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J.L.; Ziegler, A.M. Gender differences in subjective and physiological responses to caffeine and the role of steroid hormones. J. Caffeine Res. 2011, 1, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All | No Soda | Occasional Soda | Daily Soda | p | No ED | Occasional ED | Daily ED | p | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Sex | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 5442 | 51.6 | 2053 | 37.7 | 2818 | 51.8 | 571 | 10.5 | 3698 | 69.8 | 1320 | 24.9 | 277 | 5.2 | ||

| Male | 5106 | 48.4 | 1381 | 27.0 | 2811 | 55.1 | 914 | 17.9 | 2779 | 55.8 | 1691 | 33.9 | 507 | 10.2 | ||

| Age | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| <14 | 1248 | 11.8 | 394 | 11.4 | 678 | 12.0 | 176 | 11.8 | 739 | 61.1 | 384 | 31.8 | 86 | 7.1 | ||

| 15 | 2826 | 26.7 | 883 | 25.6 | 1555 | 27.5 | 388 | 25.9 | 1739 | 62.9 | 809 | 29.3 | 215 | 7.8 | ||

| 16 | 2827 | 26.7 | 847 | 24.5 | 1515 | 26.8 | 365 | 24.4 | 1747 | 63.8 | 782 | 28.6 | 209 | 7.6 | ||

| 17 | 2378 | 22.4 | 806 | 23.4 | 1234 | 21.8 | 338 | 22.6 | 1487 | 64.2 | 658 | 28.4 | 171 | 7.4 | ||

| >18 | 1324 | 12.4 | 421 | 12.2 | 675 | 11.9 | 228 | 15.3 | 797 | 61.2 | 391 | 30.1 | 113 | 8.7 | ||

| Grade | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| 9th | 2937 | 27.9 | 909 | 26.6 | 1612 | 28.7 | 416 | 28.1 | 1721 | 60.3 | 914 | 32.0 | 219 | 7.7 | ||

| 10th | 2862 | 27.2 | 900 | 26.3 | 1557 | 27.7 | 405 | 27.4 | 1797 | 64.1 | 775 | 27.7 | 230 | 8.2 | ||

| 11th | 2633 | 25.1 | 900 | 26.3 | 1380 | 24.5 | 353 | 23.9 | 1621 | 63.9 | 736 | 29.0 | 178 | 7.0 | ||

| 12th | 2087 | 19.8 | 708 | 20.7 | 1073 | 19.1 | 306 | 20.7 | 1318 | 64.1 | 584 | 28.4 | 155 | 7.5 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 253 | 2.4 | 52 | 1.5 | 159 | 2.8 | 42 | 2.9 | 144 | 57.4 | 79 | 31.5 | 28 | 11.2 | ||

| Asian | 314 | 3.0 | 138 | 4.1 | 149 | 2.7 | 27 | 1.8 | 243 | 78.9 | 54 | 17.5 | 11 | 3.6 | ||

| Black/African American | 1098 | 10.5 | 377 | 11.1 | 548 | 9.8 | 173 | 11.8 | 517 | 52.3 | 339 | 34.3 | 133 | 13.4 | ||

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 55 | 0.5 | 13 | 0.4 | 32 | 0.6 | 10 | 0.7 | 24 | 46.2 | 22 | 42.3 | 6 | 11.5 | ||

| White/Caucasian | 5241 | 50.2 | 1682 | 49.5 | 2825 | 50.6 | 734 | 49.9 | 3537 | 67.6 | 1407 | 26.9 | 285 | 5.5 | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 428 | 4.1 | 134 | 3.9 | 239 | 4.3 | 55 | 3.7 | 221 | 55.8 | 141 | 35.6 | 34 | 8.6 | ||

| Multiple Race–Hispanic | 2543 | 24.3 | 821 | 24.2 | 1357 | 24.3 | 365 | 24.8 | 1398 | 57.1 | 802 | 32.8 | 248 | 10.1 | ||

| Multiple Race–Non-Hispanic | 515 | 5.0 | 178 | 5.2 | 271 | 4.9 | 66 | 4.5 | 331 | 65.4 | 138 | 27.3 | 37 | 7.3 | ||

| Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | p | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | ||

| BMI Percentile | 61.6 | 0.29 | 61.6 | 0.49 | 61.9 | 0.39 | 60.1 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 60.8 | 0.37 | 62.9 | 0.54 | 62.1 | 1.1 | 0.005 |

| Estimated Caffeine Use (mg/Day) | 64.5 | 1.15 | 21.7 a | 1.20 | 51.9 b | 0.96 | 209.2 c | 5.2 | <0.001 | 16.8 | 0.34 | 84.5 | 0.78 | 381.7 | 7.5 | <0.001 |

| Hours of Sleep/Night | 6.45 | 0.01 | 6.43 a | 0.03 | 6.51 b | 0.02 | 6.29 c | 0.04 | <0.001 | 6.5 | 0.02 | 6.4 | 0.03 | 6.3 | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Soda | Energy Drinks | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Soda | No Soda | Daily vs. No Soda | Daily EDs | No EDs | Daily vs. No EDs | |||||

| N | N | Odds Ratio | (95% CI) | p | N | N | Odds Ratio | (95% CI) | p | |

| Cigarette Smoking in past 30 days | ||||||||||

| Everyday | 52 | 21 | 5.95 | (3.6, 9.9) | <0.001 | 40 | 42 | 8.36 | (5.3, 13.1) | <0.001 |

| 20–29 Days | 9 | 3 | 10.02 | (2.2, 47.3) | 0.004 | 6 | 6 | 7.65 | (2.3, 25.2) | <0.001 |

| 10–19 Days | 14 | 11 | 2.95 | (1.3, 6.6) | 0.009 | 10 | 23 | 4.23 | (2.0, 8.9) | <0.001 |

| 1–9 Days | 73 | 100 | 1.82 | (1.3, 2.5) | <0.001 | 38 | 180 | 1.89 | (1.3, 2.7) | <0.001 |

| 0 Days | 1300 | 3263 | ref | ref | ref | 667 | 6173 | Ref | ref | ref |

| Vape Use in past 30 days | ||||||||||

| Everyday | 80 | 39 | 7.27 | (4.8, 11.1) | <0.001 | 38 | 134 | 10.92 | (6.8, 17.5) | <0.001 |

| 20–29 Days | 25 | 32 | 2.99 | (1.7, 5.2) | <0.001 | 4 | 77 | 1.98 | (0.7, 5.6) | 0.20 |

| 10–19 Days | 24 | 32 | 2.54 | (1.4, 4.4) | 0.001 | 12 | 90 | 4.65 | (2.3, 9.3) | <0.001 |

| 1–9 Days | 51 | 92 | 1.94 | (1.3, 2.8) | <0.001 | 18 | 240 | 2.83 | (1.6, 4.9) | <0.001 |

| 0 Days | 203 | 704 | ref | ref | ref | 50 | 1757 | Ref | ref | ref |

| Alcohol Use in past 30 days | ||||||||||

| Everyday | 47 | 20 | 6.41 | (3.7, 11.0) | <0.001 | 45 | 20 | 19.54 | (11.4, 33.6) | <0.001 |

| 20–29 Days | 16 | 12 | 3.59 | (1.7, 7.6) | <0.001 | 7 | 18 | 3.62 | (1.5, 8.7) | 0.004 |

| 10–19 Days | 44 | 33 | 3.52 | (2.2, 5.6) | <0.001 | 26 | 67 | 3.67 | (2.3, 5.8) | <0.001 |

| 1–9 Days | 489 | 1013 | 1.29 | (1.1, 1.5) | <0.001 | 209 | 1975 | 0.99 | (0.8, 1.2) | 0.90 |

| 0 Days | 823 | 2231 | ref | ref | ref | 452 | 4196 | Ref | ref | ref |

| Marijuana Use in past 30 days | ||||||||||

| 40+ Times | 123 | 57 | 5.54 | (3.9, 7.7) | <0.001 | 83 | 148 | 5.11 | (3.8, 6.8) | <0.001 |

| 20–39 Times | 28 | 31 | 2.32 | (1.4, 3.9) | 0.002 | 10 | 73 | 1.26 | (0.6, 2.5) | 0.495 |

| 10–19 Times | 46 | 56 | 2.09 | (1.4, 3.1) | <0.001 | 31 | 106 | 2.56 | (1.7, 3.9) | <0.001 |

| 1–9 Times | 270 | 762 | 0.87 | (0.7, 1.0) | 0.079 | 129 | 1455 | 0.80 | (0.6, 0.9) | 0.034 |

| 0 Times | 996 | 2500 | ref | ref | ref | 520 | 4673 | Ref | ref | ref |

| Prescription Drugs in lifetime | ||||||||||

| 40+ Times | 59 | 35 | 3.71 | (2.4, 5.7) | <0.001 | 48 | 54 | 6.87 | (4.6, 10.3) | <0.001 |

| 20–29 Times | 21 | 15 | 3.44 | (1.7, 6.8) | <0.001 | 18 | 24 | 6.05 | (3.3, 11.2) | <0.001 |

| 10–19 Times | 30 | 42 | 1.71 | (1.1, 2.8) | 0.031 | 18 | 66 | 2.11 | (1.2, 3.6) | 0.007 |

| 1–9 Times | 152 | 239 | 1.47 | (1.2, 1.8) | <0.001 | 83 | 480 | 1.35 | (1.1, 1.7) | 0.021 |

| 0 Times | 1101 | 2541 | ref | ref | ref | 586 | 4749 | Ref | ref | ref |

| Soda | EDs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | None | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p | Daily | None | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p | |

| Sad or hopeless almost every day for 2 weeks (past 12 months) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 606 | 876 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5) | 297 | 2234 | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) | ||

| No | 1174 | 2230 | ref | 487 | 4203 | ref | ||

| Suicide attempt (past 12 months) | ||||||||

| 6+ Times | 30 | 15 | 5.5 (2.8, 10.7) | <0.001 | 33 | 24 | 13.0 (7.3, 23.3) | <0.001 |

| 4–5 Times | 6 | 14 | 1.3 (0.5, 3.5) | 0.58 | 3 | 21 | 5.7 (2.9, 11.2) | <0.001 |

| 2–3 Times | 46 | 64 | 1.8 (1.2, 2.7) | 0.003 | 32 | 126 | 4.4 (2.2, 8.9) | <0.001 |

| 1 Time | 95 | 128 | 1.9 (1.5, 2.6) | <0.001 | 43 | 225 | 8.1 (2.0, 31.6) | <0.001 |

| 0 Times | 1098 | 2852 | ref | ref | 521 | 5555 | ref | ref |

| Mental health not good (past 30 days) | ||||||||

| All 30 Days | 11 | 35 | 1.1 (0.51, 2.3) | 0.81 | 7 | 81 | 0.54 (0.19, 1.5) | 0.23 |

| 14–29 Days | 15 | 79 | 0.65 (0.34, 1.2) | 0.19 | 2 | 134 | 2.8 (0.64, 12.6) | 0.17 |

| 7–13 Days | 10 | 88 | 0.35 (0.16, 0.75) | 0.007 | 2 | 151 | 2.7 (0.77, 9.3) | 0.12 |

| 1–6 Days | 47 | 203 | 0.75 (0.47, 1.2) | 0.22 | 9 | 411 | 1.9 (0.72, 4.8) | 0.20 |

| 0 Days | 47 | 151 | ref | ref | 19 | 343 | ref | ref |

| Soda | EDs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | None | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p | Daily | None | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p | |

| Sleep | ||||||||

| <5 h | 447 | 917 | 0.88 (0.68, 1.14) | 0.34 | 145 | 348 | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.25 |

| 6 h | 370 | 754 | 0.87 (0.67, 1.13) | 0.30 | 273 | 1193 | 1.7 (1.2, 2.2) | <0.001 |

| 7 h | 345 | 926 | 0.66 (0.51, 0.86) | 0.002 | 174 | 1863 | 2.1 (1.6, 2.9) | <0.001 |

| 8 h | 201 | 593 | 0.61 (0.46, 0.81) | <0.001 | 111 | 2423 | 2.1 (1.5, 2.9) | <0.001 |

| >9 h | 113 | 203 | ref | ref | 76 | 348 | ref | ref |

| Fruit (per week) | ||||||||

| 0 times | 247 | 534 | 1.07 (0.88, 1.3) | 0.48 | 94 | 898 | 1.9 (1.4, 2.5) | <0.001 |

| 1–3 times | 459 | 1003 | 1.06 (0.89, 1.3) | 0.49 | 173 | 2275 | 2.3 (1.8, 2.9) | <0.001 |

| 4–6 times | 238 | 699 | 0.78 (0.65, 0.95) | 0.014 | 127 | 1411 | 1.9 (1.5, 2.6) | <0.001 |

| 7 times | 188 | 368 | 1.18 (0.95, 1.46) | 0.13 | 104 | 687 | 1.2 (0.92, 1.6) | 0.18 |

| 8 or more times | 366 | 843 | ref | ref | 122 | 1230 | ref | ref |

| Vegetables (per week) | ||||||||

| 0 times | 402 | 718 | 1.12 (0.97, 1.45) | 0.09 | 179 | 1345 | 2.0 (1.6, 2.5) | <0.001 |

| 1–3 times | 431 | 1073 | 0.85 (0.69, 1.03) | 0.09 | 203 | 2264 | 2.9 (2.3, 3.6) | <0.001 |

| 4–6 times | 254 | 741 | 0.73 (0.59, 0.90) | 0.004 | 125 | 1440 | 2.9 (2.3, 3.7) | <0.001 |

| 7 times | 173 | 428 | 0.84 (0.66, 1.06) | 0.14 | 105 | 727 | 1.8 (1.4, 2.4) | <0.001 |

| 8 or more times | 231 | 485 | ref | ref | 184 | 733 | ref | ref |

| Fast Food (per week) | ||||||||

| 7 times | 89 | 33 | 17.5 (11.2, 27.4) | <0.001 | 66 | 50 | 10.7 (6.9, 16.6) | <0.001 |

| 5–6 times | 54 | 34 | 10.7 (6.6, 17.3) | <0.001 | 41 | 70 | 6.1 (4.1, 9.3) | <0.001 |

| 2–4 times | 259 | 224 | 7.6 (5.8, 9.9) | <0.001 | 160 | 472 | 3.4 (2.2, 5.2) | <0.001 |

| 1–2 times | 344 | 678 | 3.3 (2.6, 4.3) | <0.001 | 228 | 1184 | 1.84 (1.1, 3.2) | <0.001 |

| 0 times | 114 | 731 | ref | ref | 101 | 884 | ref | ref |

| Physical Activity (2 h per day) | ||||||||

| 0 days | 429 | 909 | 1.03 (0.84, 1.28) | 0.76 | 349 | 1293 | 1.8 (1.2, 2.8) | 0.009 |

| 1–2 days | 634 | 1318 | 1.07 (0.87, 1.31) | 0.54 | 304 | 2414 | 1.3 (0.85, 1.98) | 0.23 |

| 3–4 days | 118 | 377 | 0.69 (0.52, 0.90) | 0.007 | 39 | 884 | 0.42 (0.31, 0.94) | <0.001 |

| 5–6 days | 133 | 422 | 0.69 (0.53, 0.91) | 0.008 | 33 | 993 | 0.22 (0.16, 0.29) | <0.001 |

| 7 days | 175 | 393 | ref | ref | 61 | 892 | ref | ref |

| Boys | Girls | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Soda | No Soda | Daily Adjusted Odds Ratio | Daily Soda | No Soda | Daily Adjusted Odds Ratio | |||

| N | N | (95% CI) | p | N | N | (95% CI) | p | |

| Vape Use (past 30 days) | ||||||||

| Everyday | 60 | 17 | 6.9 (3.9, 12.4) | <0.001 | 18 | 22 | 6.6 (3.3, 13.1) | <0.001 |

| 20–29 Days | 18 | 14 | 2.4 (1.2, 5.1) | 0.017 | 6 | 17 | 3.1 (1.1, 8.2) | 0.027 |

| 10–19 Days | 17 | 13 | 2.6 (1.2, 5.5) | 0.014 | 6 | 19 | 2.4 (0.9, 6.1) | 0.081 |

| 1–9 Days | 31 | 29 | 2.0 (1.2, 3.5) | 0.011 | 20 | 63 | 2.2 (1.2, 4.0) | 0.008 |

| 0 Days | 142 | 268 | ref | ref | 60 | 428 | ref | ref |

| Alcohol Use (past 30 days) | ||||||||

| Everyday | 29 | 16 | 3.3 (1.8, 6.2) | <0.001 | 14 | 4 | 17.8 (5.0, 62.9) | <0.001 |

| 20–29 Days | 10 | 6 | 3.1 (1.1, 8.7) | 0.28 | 6 | 6 | 4.0 (1.3, 12.6) | 0.017 |

| 10–19 Days | 32 | 15 | 3.8 (2.0, 7.2) | <0.001 | 10 | 18 | 2.2 (1.0, 4.9) | 0.044 |

| 1–9 Days | 280 | 345 | 1.5 (1.2, 1.8) | <0.001 | 206 | 661 | 1.3 (1.0, 1.5) | 0.024 |

| 0 Days | 500 | 921 | ref | ref | 317 | 1295 | ref | ref |

| Marijuana Use (past 30 days) | ||||||||

| 40+ Times | 88 | 31 | 5.1 (3.3, 7.9) | <0.001 | 32 | 24 | 4.8 (2.8, 8.3) | <0.001 |

| 20–39 Times | 17 | 14 | 2.3 (1.1, 4.7) | 0.029 | 11 | 17 | 2.3 (1.1, 5.2) | 0.037 |

| 10–19 Times | 30 | 21 | 2.3 (1.3, 4.1) | 0.004 | 16 | 34 | 1.9 (1.0, 3.5) | 0.042 |

| 1–9 Times | 151 | 264 | 0.96 (0.78, 1.2) | 0.715 | 117 | 497 | 0.87 (0.69, 1.1) | 0.246 |

| 0 Times | 599 | 1022 | ref | ref | 387 | 1457 | ref | ref |

| Been in a Physical Fight (past 30 days) | ||||||||

| 12+ Times | 56 | 30 | 3.6 (2.3, 5.8) | <0.001 | 14 | 12 | 4.9 (2.3, 11.0) | <0.001 |

| 8–11 Times | 11 | 9 | 2.3 (0.93, 5.5) | 0.072 | 8 | 8 | 3.9 (1.4, 10.7) | 0.010 |

| 4–7 Times | 39 | 37 | 2.0 (1.2, 3.3) | 0.004 | 18 | 24 | 3.6 (1.9, 6.7) | <0.001 |

| 1–3 Times | 216 | 212 | 1.9 (1.5, 2.3) | <0.001 | 107 | 163 | 3.1 (2.4, 4.1) | <0.001 |

| 0 Times | 573 | 1060 | ref | ref | 416 | 1826 | ref | ref |

| Sleep (per school night) | ||||||||

| <5 h | 241 | 349 | 0.92 (0.64, 1.3) | 0.624 | 201 | 557 | 1.1 (0.73, 1.7) | 0.62 |

| 6 h | 222 | 272 | 1.1 (0.73, 1.5) | 0.792 | 145 | 479 | 0.93 (0.61, 1.4) | 0.76 |

| 7 h | 222 | 372 | 0.78 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.172 | 118 | 549 | 0.66 (0.42, 1.0) | 0.058 |

| 8 h | 137 | 260 | 0.69 (0.48, 1.0) | 0.052 | 64 | 328 | 0.60 (0.38, 0.97) | 0.036 |

| >9 h | 75 | 98 | ref | ref | 34 | 105 | ref | ref |

| Fast Food (per week) | ||||||||

| 7 times | 48 | 19 | 13.4 (7.3, 24.3) | <0.001 | 36 | 14 | 20.9 (10.5, 41.7) | <0.001 |

| 5– 6 times | 23 | 14 | 8.8 (4.3, 18.1) | <0.001 | 31 | 20 | 13.3 (6.9, 25.3) | <0.001 |

| 3–4 times | 141 | 85 | 8.5 (5.8, 12.5) | <0.001 | 116 | 135 | 7.0 (4.7, 10.4) | <0.001 |

| 1–2 times | 211 | 257 | 4.3 (3.1, 5.9) | <0.001 | 129 | 419 | 2.6 (1.8, 3.7) | <0.001 |

| 0 times | 65 | 326 | ref | ref | 48 | 398 | ref | ref |

| Boys | Girls | |||||||

| Daily ED | No ED | Daily Adjusted Odds Ratio | Daily ED | No ED | Daily Adjusted Odds Ratio | |||

| N | N | (95% CI) | p | N | N | (95% CI) | p | |

| Vape Use (past 30 days) | ||||||||

| Everyday | 28 | 69 | 10.3 (5.9, 18.1) | <0.001 | 8 | 65 | 7.2 (2.9, 18.0) | <0.001 |

| 20–29 Days | 2 | 34 | 2.9 (1.5, 6.1) | 0.003 | 2 | 41 | 3.8 (1.1, 13.4) | 0.036 |

| 10–19 Days | 10 | 37 | 1.5 (0.66, 3.5) | 0.33 | 1 | 52 | 5.9 (0.7, 48.7) | 0.10 |

| 1–9 Days | 14 | 99 | 6.6 (1.5, 29.6) | 0.013 | 4 | 140 | 2.5 (0.5, 12.6) | 0.26 |

| 0 Days | 35 | 837 | ref | ref | 15 | 903 | ref | ref |

| Alcohol Use (past 30 days) | ||||||||

| Everyday | 26 | 17 | 9.6 (5.1, 17.9) | <0.001 | 15 | 3 | 69.1 (19.8, 241.0) | <0.001 |

| 20–29 Days | 4 | 7 | 8.3 (4.3, 15.7) | <0.001 | 3 | 11 | 81.5 (23.1, 287.9) | <0.001 |

| 10–19 Days | 22 | 34 | 2.2 (0.98, 5.0) | 0.057 | 2 | 33 | 82.2 (12.4, 544.1) | <0.001 |

| 1–9 Days | 134 | 762 | 2.6 (0.7, 10.2) | 0.18 | 73 | 1204 | 18.3 (3.1, 108.5) | 0.001 |

| 0 Days | 283 | 1834 | ref | ref | 167 | 2325 | ref | ref |

| Marijuana Use (past 30 days) | ||||||||

| 40+ Times | 61 | 81 | 4.6 (3.2, 6.5) | <0.001 | 19 | 65 | 4.2 (2.5, 7.1) | <0.001 |

| 20–39 Times | 8 | 28 | 5.8 (3.8, 8.7) | <0.001 | 2 | 45 | 4.9 (2.7, 8.8) | <0.001 |

| 10–19 Times | 21 | 49 | 1.8 (0.99, 3.4) | 0.053 | 10 | 57 | 1.7 (0.73, 3.9) | 0.22 |

| 1–9 Times | 74 | 581 | 2.6 (1.1, 6.2) | 0.027 | 53 | 872 | 6.7 (1.5, 30.1) | 0.014 |

| 0 Times | 328 | 1997 | ref | ref | 186 | 2632 | ref | ref |

| Been in a Physical Fight (past 30 days) | ||||||||

| 12+ Times | 40 | 56 | 5.7 (3.8, 8.8) | <0.001 | 16 | 16 | 17.3 (8.5, 35.2) | <0.001 |

| 8–11 Times | 8 | 18 | 2.3 (1.5, 3.7) | <0.001 | 4 | 13 | 6.1 (2.9, 13.0) | 0.010 |

| 4–7 Times | 28 | 56 | 1.5 (0.8, 2.7) | 0.21 | 9 | 49 | 5.4 (2.0, 14.6) | <0.001 |

| 1–3 Times | 131 | 423 | 1.9 (0.7, 4.9) | 0.20 | 53 | 327 | 3.2 (0.87, 12.1) | 0.081 |

| 0 Times | 277 | 2190 | ref | ref | 187 | 3269 | ref | ref |

| Sleep (per school night) | ||||||||

| <5 h | 137 | 588 | 0.89 (0.60, 1.3) | 0.59 | 106 | 925 | 1.1 (0.67, 1.8) | 0.72 |

| 6 h | 114 | 583 | 1.6 (1.1, 2.3) | 0.01 | 55 | 906 | 2.0 (1.2, 3.5) | 0.008 |

| 7 h | 116 | 842 | 2.1 (1.4, 3.0) | <0.001 | 54 | 1008 | 2.3 (1.4, 3.9) | 0.002 |

| 8 h | 77 | 547 | 1.99 (1.3, 3.0) | <0.001 | 34 | 640 | 2.3 (1.3, 4.1) | 0.004 |

| >9 h | 50 | 175 | ref | ref | 22 | 171 | ref | ref |

| Fast Food (per week) | ||||||||

| 7 times | 42 | 20 | 11.7 (6.5, 21.3) | <0.001 | 19 | 29 | 9.4 (4.8, 18.4) | <0.001 |

| 5–6 times | 19 | 25 | 6.3 (3.6, 11.0) | <0.001 | 22 | 44 | 6.1 (3.3, 11.4) | <0.001 |

| 3–4 times | 96 | 161 | 3.5 (2.0, 6.5) | <0.001 | 62 | 309 | 3.2 (1.7, 6.0) | <0.001 |

| 1–2 times | 148 | 446 | 2.8 (1.2, 6.2) | 0.012 | 78 | 732 | 1.3 (0.6, 2.8) | 0.51 |

| 0 times | 66 | 364 | ref | ref | 35 | 510 | ref | ref |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suresh, S.; Temple, J.L. Relationships Among Soda and Energy Drink Consumption, Substance Use, Mental Health and Risk-Taking Behavior in Adolescents. Children 2024, 11, 1448. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121448

Suresh S, Temple JL. Relationships Among Soda and Energy Drink Consumption, Substance Use, Mental Health and Risk-Taking Behavior in Adolescents. Children. 2024; 11(12):1448. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121448

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuresh, Surya, and Jennifer L. Temple. 2024. "Relationships Among Soda and Energy Drink Consumption, Substance Use, Mental Health and Risk-Taking Behavior in Adolescents" Children 11, no. 12: 1448. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121448

APA StyleSuresh, S., & Temple, J. L. (2024). Relationships Among Soda and Energy Drink Consumption, Substance Use, Mental Health and Risk-Taking Behavior in Adolescents. Children, 11(12), 1448. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121448