A Scoping Review of Trauma-Informed Pediatric Interventions in Response to Natural and Biologic Disasters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

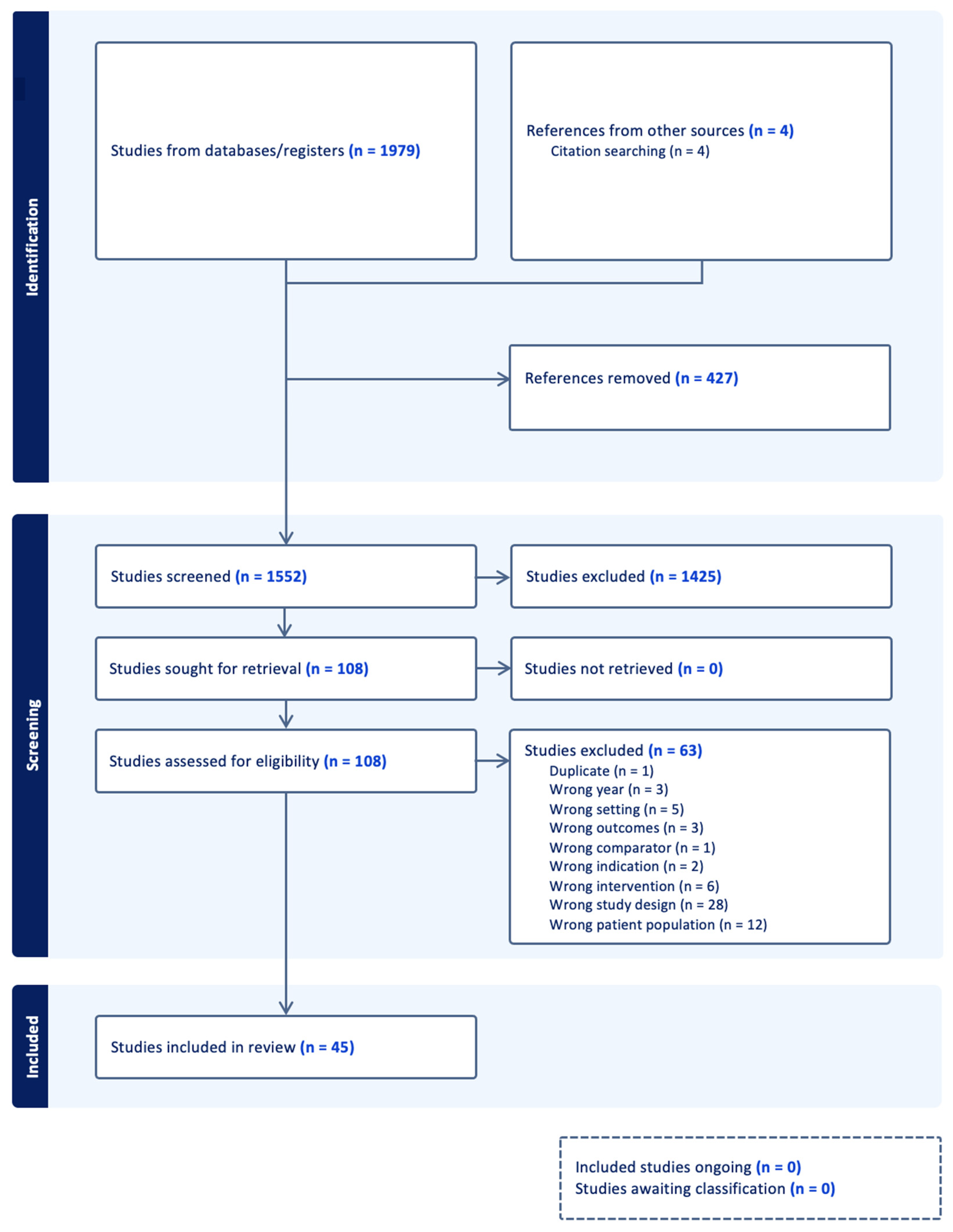

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Extracted Articles

3.2. Demographics of Participants

3.3. Study Design Features

3.4. Description of the Constructs and Measures

3.5. Features of the Treatments

3.6. Findings

3.7. Follow-Up for Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Available online: https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/children-and-covid-19-state-level-data-report/ (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Available online: https://media.ifrc.org/ifrc/world- (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Carliner, H.; Keyes, K.M.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Meyers, J.L.; Dunn, E.C.; Martins, S.S. Childhood trauma and illicit drug use in adolescence: A population-based national comorbidity survey replication-adolescent supplement study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, B.S.; Lewis, R.; Livings, M.S.; La Greca, A.M.; Esnard, A.M. Posttraumatic stress symptom trajectories among children after disaster exposure: A review. J. Trauma. Stress 2017, 30, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- University of Central Florida. Available online: https://www.ucf.edu/online/leadership-management/news/the-disaster-management-cycle (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- Cohen, J.A.; Mannarino, A.P.; Deblinger, E. Treating Trauma and Traumatic Grief in Children and Adolescents, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Available online: https://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/interventions/tgcta_fact_sheet.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Civilotti, C.; Margola, D.; Zaccagnino, M.; Cussino, M.; Callerame, C.; Vicini, A.; Fernandez, I. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing in Child and Adolescent Psychology: A Narrative Review. Curr. Treat. Options Psych. 2021, 8, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pityaratstian, N.; Piyasil, V.; Ketumarn, P.; Sitdhiraksa, N.; Ularntinon, S.; Pariwatcharakul, P. Randomized Controlled Trial of Group Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Children and Adolescents Exposed to Tsunami in Thailand. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2015, 43, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, S.B.; Weinrich, S.; Weinrich, M.; Garrison, C.; Addy, C.; Hardin, T.L. Effects of a long-term psychosocial nursing intervention on adolescents exposed to catastrophic stress. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2002, 23, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catani, C.; Kohiladevy, M.; Ruf, M.; Schauer, E.; Elbert, T.; Neuner, F. Treating children traumatized by war and Tsunami: A comparison between exposure therapy and meditation-relaxation in North-East Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry 2009, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adúriz, M.E.; Bluthgen, C.; Knopfler, C. Helping child flood victims using group EMDR intervention in Argentina: Treatment outcome and gender differences. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2022, 16, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzano, A.N.; Sun, Y.; Chavez-Gray, V.; Akintimehin, T.; Gustat, J.; Barrera, D.; Roi, C. Effect of Yoga and Mindfulness Intervention on Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression in Young Adolescents Attending Middle School: A Pragmatic Community-Based Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial in a Racially Diverse Urban Setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishida, K.; Hida, N.; Matsubara, K.; Oguni, M.; Ishikawa, S.I. Implementation of a Transdiagnostic Universal Prevention Program on Anxiety in Junior High School Students After School Closure During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Prev. 2023, 44, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleider, J.L.; Mullarkey, M.C.; Fox, K.R.; Dobias, M.L.; Shroff, A.; Hart, E.A.; Roulston, C.A. A randomized trial of online single-session interventions for adolescent depression during COVID-19. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2022, 6, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentini, C.; Lauriola, M.; Giuliani, A.; Maslovaric, G.; Tambelli, R.; Fernandez, I.; Pagani, M. Dealing With the Aftermath of Mass Disasters: A Field Study on the Application of EMDR Integrative Group Treatment Protocol With Child Survivors of the 2016 Italy Earthquakes. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardayati, Y.; Mustikasari Panjaitan, R. Thought stopping as a strategy for controlling adolescent negative thoughts related to earthquakes. Enferm. Clin. 2020, 30, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiak, K.; Merry, S.; Frampton, C.; Moor, S. Delivering solid treatments on shaky ground: Feasibility study of an online therapy for child anxiety in the aftermath of a natural disaster. Psychother. Res. 2016, 28, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karairmak, O.; Aydin, G. Reducing earthquake-related fears in victim and nonvictim children. J. Genet. Psychol. 2008, 169, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaycox, L.H.; Cohen, J.A.; Mannarino, A.P.; Walker, D.W.; Langley, A.K.; Gegenheimer, K.L.; Scott, M.; Schonlau, M. Children’s mental health care following Hurricane Katrina: A field trial of trauma-focused psychotherapies. J. Traum. Stress 2010, 23, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaidou, I.; Stavrou, E.; Leonidou, G. Building Primary-School Children’s Resilience through a Web-Based Interactive Learning Environment: Quasi-Experimental Pre-Post Study. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2021, 4, e27958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orengo-Aguayo, R.; Dueweke, A.R.; Nicasio, A.; de Arellano, M.A.; Rivera, S.; Cohen, J.A.; Mannarino, A.P.; Stewart, R.W. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy with Puerto Rican youth in a post-disaster context: Tailoring, implementation, and program evaluation outcomes. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 129, 105671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Léger-Goodes, T.; Mageau, G.A.; Taylor, G.; Herba, C.M.; Chadi, N.; Lefrançois, D. Online art therapy in elementary schools during COVID-19: Results from a randomized cluster pilot and feasibility study and impact on mental health. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2021, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Léger-Goodes, T.; Mageau, G.A.; Joussemet, M.; Herba, C.; Chadi, N.; Lefrançois, D.; Camden, C.; Bussières, È.L.; Taylor, G.; et al. Philosophy for children and mindfulness during COVID-19: Results from a randomized cluster trial and impact on mental health in elementary school students. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 107, 110260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.C.; Yang, P.; Yen, C.F.; Liu, T.L. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for treating psychological disturbances in Taiwanese adolescents who experienced Typhoon Morakot. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2015, 31, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Shen, W.; Weng, S. Intervention of adolescent mental health during the outbreak of COVID-19 using aerobic exercise combined with acceptance and commitment therapy. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 124, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzaroni, E.; Invernizzi, R.; Fogliato, E.; Pagani, M.; Maslovaric, G. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Emergency and Remote Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Group Therapy With Adolescents and Young Adults: Overcoming Lockdown with the Butterfly Hug. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 701381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y. Intervention effect of the video health education model based on solution-focused theory on adolescents’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Iran. J. Public Health 2021, 50, 2202–2210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shooshtary, M.H.; Panaghi, L.; Moghadam, J.A. Outcome of cognitive behavioral therapy in adolescents after natural disaster. J. Adolesc. Health 2008, 42, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, W. Intervention Effect of Research-based Psychological Counseling on Adolescents’ Mental Health during the COVID-19 Epidemic. Psychiatr. Danub. 2021, 33, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemtob, C.M.; Taylor, K.B.; Woo, L.; Coel, M.N. Mixed handedness and trauma symptoms in disaster-exposed adolescents. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2001, 189, 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Lei, F.; Lei, S.; Chen, J. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in Students Aged 8–18 in Wuhan, China 6 Months after the Control of COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 740575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Benoit, M. Successful strategies for treating traumatized children in challenging circumstances. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, S312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Kong, Y.; Bu, H.; Guan, Q.; Chen, Z.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, J. The online strength-informed acceptance and commitment therapy among COVID-19 affected adolescents. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2022, 32, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, I. EMDR as treatment of post-traumatic reactions: A field study on child victims of an earthquake. Educ. Child Psychol. 2007, 24, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadari, S.; Farokhzadian, J.; Mangolian Shahrbabaki, P. Effectiveness of resilience training on social self-efficacy of the elementary school girls during COVID-19 outbreak. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannopoulou, I.; Dikaiakou, A.; Yule, W. Cognitive-behavioural group intervention for PTSD symptoms in children following the Athens 1999 earthquake: A pilot study. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2006, 11, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslovaric, G.; Zaccagnino, M.; Mezzaluna, C.; Perilli, S.; Trivellato, D.; Longo, V.; Civilotti, C. The Effectiveness of Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Integrative Group Protocol with Adolescent Survivors of the Central Italy Earthquake. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadag, M.; Topal, Z.; Ezer, R.; Gokcen, C. Use of EMDR-Derived Self-Help Intervention in Children in the Period of COVID-19: A Randomized- Controlled Study. J. EMDR Pract. Res. 2021, 15, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, T.; Masuyama, A.; Shinkawa, H.; Sugawara, D. Impact of a single school-based intervention for COVID-19 on improving mental health among Japanese children. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keypour, M.; Arman, S.; Maracy, M.R. The effectiveness of cognitive behavioral stress management training on mental health, social interaction and family function in adolescents of families with one Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) positive member. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2011, 16, 741–749. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, J.; Alie, C.; Jonas, B.; Brown, E.; Sherr, L. A quasi-experimental evaluation of a community-based art therapy intervention exploring the psychosocial health of children affected by HIV in South Africa. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2011, 16, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shen, W.W.; Gao, K.; Lam, C.S.; Chang, W.C.; Deng, H. Effectiveness RCT of a CBT intervention for youths who lost parents in the Sichuan, China, earthquake. Psychiatr Serv. 2014, 65, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, K.J.; Price, M.; Adams, Z.; Stauffacher, K.; McCauley, J.; Danielson, C.K.; Knapp, R.; Hanson, R.F.; Davidson, T.M.; Amstadter, A.B.; et al. Web Intervention for Adolescents Affected by Disaster: Population-Based Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 54, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.C.; Garriga, A.; Egea, C. Psychological Intervention in Primary Care After Earthquakes in Lorca, Spain. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2015, 17, PMC4468883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, D.S.; Plummer, C.A.; Fisher, R.M.; Bankston, T.Q. Weathering the Storm: Persistent Effects and Psychological First Aid with Children Displaced by Hurricane Katrina. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2010, 3, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloum, A.; Overstreet, S. Grief and trauma intervention for children after disaster: Exploring coping skills versus trauma narration. Behav. Res. Ther. 2012, 50, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, L.K.; Weems, C.F. Cognitive-behavior therapy for disaster-exposed youth with posttraumatic stress: Results from a multiple-baseline examination. Behav Ther. 2011, 42, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osofsky, H.; Osofsky, J.; Hansel, T.; Lawrason, B.; Speier, A. Building Resilience after Disasters through the Youth Leadership Program: The Importance of Community and Academic Partnerships on Youth Outcomes. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2018, 12, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, T.; Thompson, S.J. Enhancing Coping and Supporting Protective Factors After a Disaster: Findings From a Quasi-Experimental Study. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2016, 26, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, N.K.; Cobham, V.E.; McDermott, B. Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Narratives of Children and Adolescents. Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, D.; Koseki, S.; Ohtani, T. A Brief School-Based Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention for Japanese Adolescents With Severe Posttraumatic Stress. J. Trauma. Stress 2016, 29, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, A.; Steele, R.G.; Singh, M.N. Systematic Review on the Application of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) for Preschool-Aged Children. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 24, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezayat, A.A.; Sahebdel, S.; Jafari, S.; Kabirian, A.; Rahnejat, A.M.; Farahani, R.H.; Mosaed, R.; Nour, M.G. Evaluating the Prevalence of PTSD among Children and Adolescents after Earthquakes and Floods: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 1265–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, T.M.; Alderfer, M.A.; Boerner, K.E.; Hilliard, M.E.; Hood, A.M.; Modi, A.C.; Wu, Y.P. Editorial: Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion: Reporting Race and Ethnicity in the Journal of Pediatric Psychology. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2021, 46, 731–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.; Goodman, R. Strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a dimensional measure of child mental health. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 48, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplow, J.B.; Rolon-Arroyo, B.; Layne, C.M.; Rooney, E.; Oosterhoff, B.; Hill, R.; Steinberg, A.M.; Lotterman, J.; Gallagher, K.A.; Pynoos, R.S. Validation of the UCLA PTSD reaction index for DSM-5: A developmentally informed assessment tool for youth. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Results |

|---|---|

| Cochrane Trials and Reviews | 407 |

| EBSCO CINAHL | 480 |

| Ovid Medline | 715 |

| Ovid PsycInfo | 373 |

| Hand Searching | 4 |

| Total | 1979 |

| Total with duplicates removed | 1552 |

| Study | Disaster Type Location | Ages Studied (years) Sex (%, n=) Race/Ethnicity (%, n=) | Sample Size | Measures | Intervention(s) | Summary of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. Pityaratstian (2007) [9] | Natural disaster—Tsunami Thailand | Range: 9–15 59.4% female (n = 95) Not U.S. based. | N = 160 |

|

|

|

| S. Hardin (2002) [10] | Natural disaster—Hurricane Hugo South Carolina, United States | Range: 13–18 50% female (n = 515) 44% white (n = 453) 54% black (n = 556) | N = 1030 |

|

|

|

| C. Catani (2009) [11] | Natural Disaster—Tsunami North-East Sri Lanka | Range = 8–14 45% female (n = 14) Not U.S. based. | N = 31 |

|

|

|

| M. Adúriz (2009) [12] | Natural Disaster—Flood Argentina | Range: 7–17 51% female (n = 63) Not U.S. based. | N = 124 |

|

|

|

| A. Bazzano (2022) [13] | Pandemic—COVID-19 New Orleans, LA | Range: 11–14 46% female (n = 40) 55 (67.1%) African American | N = 86 |

|

|

|

| 19 (23.2%) white 6 (7.3%) Asian 2 (2.4%) multi-racial | ||||||

| K. Kishida (2022) [14] | Pandemic—COVID-19 Japan | Range: 12–13 62% female (n = 74) Not U.S. based. | N = 120 |

|

|

|

| J. Schleider (2022) [15] | Pandemic—COVID-19 United States | Range: 13–16 88% female (n = 2158) | N = 2452 |

|

|

|

| C. Trentini (2018) [16] | Natural Disaster—Earthquake Umbria, Italy | Range: 5–13 % Sex not given Not U.S. based. | N = 332 |

|

|

|

| Y. Hardayati (2019) [17] | Natural Disaster—Earthquake Indonesia | Range: 15–17 80% female (n = 90) Not U.S. based. | N = 112 |

|

|

|

| K. Stasiak (2016) [18] | Natural Disaster—Earthquake New Zealand | Range: 7–15 53% female (n = 22) Not U.S. based. | N = 42 |

|

|

|

| O. Karairmak (2008) [19] | Natural Disaster—Earthquake Turkey | Range: 4th through 8th grade 32% female (n = 85) Not U.S. based. | N = 266 |

|

|

|

| L. Jaycox (2010) [20] | Natural Disaster—Hurricane Louisiana | Range: 11.6 ± 1.4 56% female (n = 66) Assigned by School for Treatment

| N = 118 |

|

|

|

| ||||||

| I. Nicolaidou (2021) [21] | Pandemic—COVID-19 Cyprus | Range: 9–10 49% female (n = 20) Not U.S. based. | N = 41 |

|

|

|

| R. Orengo- Aguayo (2022) [22] | Natural Disaster –Hurricane & Earthquake Puerto Rico | Range: 5–18 48% female (n = 47) Did not have Race/Ethnicity data. | N = 56 |

|

|

|

| C. Malbouef-Hurtubise (2021) [23] | Pandemic—COVID-19 Canada | Mean: 11.3 50% female (n = 11) Not U.S. based. | N = 22 |

|

|

|

| C. Malbouef-Hurtubise (2021) [24] | Pandemic—COVID-19 Canada | Mean: 8.18 43% female (n = 20) Not U.S. based. | N = 37 |

|

|

|

| T. Tang (2015) [25] | Natural Disaster—Typhoon Taiwan | Range: 12–15 54% female (n = 45) Not U.S. based. | N = 83 |

|

|

|

| W. Xu (2021) [26] | Pandemic—COVID-19 Fuijan Province, China | Range: 12–19 % female unknown Not U.S. based. | N = 90 |

|

|

|

| E. Lazzaroni (2021) [27] | Pandemic—COVID-19 Italy | Range: 13–24 84% female (n = 42) Not U.S. based. | N = 50 |

|

|

|

| J. Li (2021) [28] | Pandemic—COVID-19 Anhui Province, China | Mean: Intervention: 15.18 ± 1.37 48% female (n = 29) Control: 15.24 ± 1.38 47% female (n = 27) Not U.S. based. | N = 128 |

|

|

|

| M. Shooshtary (2008) [29] | Natural Disaster—Earthquake Bam, Iran | Range: 11–20 Control: 60% female (n = 20) Intervention: 53% female (n = 72) Not U.S. based. | N = 168 |

|

|

|

| J. Zhang (2021) [30] | Pandemic—COVID-19 Shandong Province, China | Range: 12–18 47% female (n = 75) Not U.S. based. | N = 160 |

|

|

|

| C. Chemtob (2002) [31] | Natural Disaster—Hurricane Hawaii, USA | Range: 6–12 61% female (n = 151) “No significant difference” for ethnicity effects. Race/Ethnicity not provided. | N = 248 |

|

|

|

| J. Chen (2021) [32] | Pandemic—COVID-19 Zheijang Province, China | Range: 13–16 49% female (n = 35) Not U.S. based. | N = 72 |

|

|

|

| J. Cohen (2021) [33] | Pandemic—COVID-19 Puerto Rico | Range: “Children” % female unknown Not U.S. based. | N = 222 |

|

|

|

| W. Duan (2022) [34] | Pandemic—COVID-19 Wuhan City, China | Range: 10–12 57% female (n = 43) Not U.S. based. | N = 76 |

|

|

|

| I. Fernandez (2007) [35] | Natural Disaster—Earthquake Molise, Italy | Range: 7–11 Sex: not provided Not U.S. based. | N = 22 |

|

|

|

| S. Gadari (2022) [36] | Pandemic—COVID-19 Southeastern Iran | Range: 9–10 100% female (n = 80) Not U.S. based. | N = 80 |

|

|

|

| I. Giannopoulou (2006) [37] | Natural Disaster—Earthquake Greece | Range: 8–12 55% female (n = 11) Not U.S. based. | N = 20 |

|

|

|

| G. Maslovaric (2017) [38] | Natural Disaster—Earthquake Valle del Tronto, Italy | Range: 13–20 44% female (n = 51) Not U.S. based. | N = 116 |

|

|

|

| M. Karadag (2021) [39] | Pandemic—COVID-19 Turkey | Range: 9.07 ± 0.8 55% female (n = 98) Not U.S. based. | N = 178 |

|

|

|

| T. Kubo (2022) [40] | Pandemic—COVID-19 Japan | Range: 12–15 47% female (n = 117) Not U.S. based. | N = 248 |

|

|

|

| M. Keypour (2011) [41] | Pandemic—AIDS Iran | Range: 13–18 40 % female (n = 14) Not U.S. based. | N = =34 |

|

|

|

| Mueller (2010) [42] | Pandemic—AIDS Knysna, South Africa | Range: 8–18 48.1% female (n = 143) Not U.S. based. | N = 297 |

|

|

|

| Pityaratstian (2015) [9] | Natural disaster—tsunami Thailand | Range: 10–15 72.2% female (n = 26) Not U.S. based. | N = 36 |

|

|

|

| Chen (2014) [43] | Natural disaster—earthquake Sichuan, China | Range: 14.50 ± 0.71 (mean ± SD) 68% female (n = 22) Not U.S. based. | N = 32 |

|

|

|

| Ruggiero (2015) [44] | Natural disaster—tornado Joplin, MO and Alabama | Range: 14.50 ± 1.7 (mean ± SD) 53% female (n = 523) 62.5% white (n = 617) 22.6% black (n = 223) 3.8% other (n = 38) 2.7% Hispanic (n = 27) | N = 987 |

|

|

|

| Martin (2015) [45] | Natural disaster—Earthquake Lorca, Spain | Range: 9–14; % female not given Not U.S. based. | N = 89 |

|

|

|

| Cain (2010) [46] | Natural disaster—Hurricane New Orleans, LA | Range: 5–15 53% female (n = 52) 95% African American (n = 94) 5% biracial (n = 5) | N = 99 |

|

|

|

| Salloum (2012) [47] | Natural disaster—Hurricane New Orleans, LA | Range: 6–12 44.3% female (n = 31) 100% African American (n = 70) | N = 70 |

|

|

|

| Taylor (2011) [48] | Natural disaster—Hurricane New Orleans, LA | Range: 8–13 67% female (n = 4) 100% African American (n = 6) | N = 6 |

|

|

|

| Osofsky (2018) [49] | Natural disaster—Hurricane New Orleans, LA | Range: 15–17 56% female (n = 119) 81% Caucasian (n = 172 8% African American (n = 17) 5% Hispanic (n = 11) 4% Other (n = 8) | N = 212 |

|

|

|

| Powell (2016) [50] | Natural disaster—Tornado Tuscaloosa, Alabama | Range: 8–12 52.9% female (n = 54) 80.2% African American (n = 82) 5.9% White (n = 6) 5.9% Latino (n = 6) 2.0% Native American (n = 2) | N = 102 |

|

|

|

| Westerman (2017) [51] | Natural disaster—Flood Queensland, Australia | Range: 8–17 54% female Not U.S. based. | N = 26 |

|

|

|

| Ito (2016) [52] | Natural disaster—Earthquake Tohoku region, Japan | Range: 15.36 ± 0.49 68% female Not U.S. based. | N = 22 |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burkhart, K.; Agarwal, N.; Kim, S.; Neudecker, M.; Ievers-Landis, C.E. A Scoping Review of Trauma-Informed Pediatric Interventions in Response to Natural and Biologic Disasters. Children 2023, 10, 1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061017

Burkhart K, Agarwal N, Kim S, Neudecker M, Ievers-Landis CE. A Scoping Review of Trauma-Informed Pediatric Interventions in Response to Natural and Biologic Disasters. Children. 2023; 10(6):1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061017

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurkhart, Kimberly, Neel Agarwal, Sehyun Kim, Mandy Neudecker, and Carolyn E. Ievers-Landis. 2023. "A Scoping Review of Trauma-Informed Pediatric Interventions in Response to Natural and Biologic Disasters" Children 10, no. 6: 1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061017

APA StyleBurkhart, K., Agarwal, N., Kim, S., Neudecker, M., & Ievers-Landis, C. E. (2023). A Scoping Review of Trauma-Informed Pediatric Interventions in Response to Natural and Biologic Disasters. Children, 10(6), 1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061017