Improving Fundamental Movement Skills during Early Childhood: An Intervention Mapping Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Physical Activity and Fundamental Movement Skill Interventions during Early Childhood

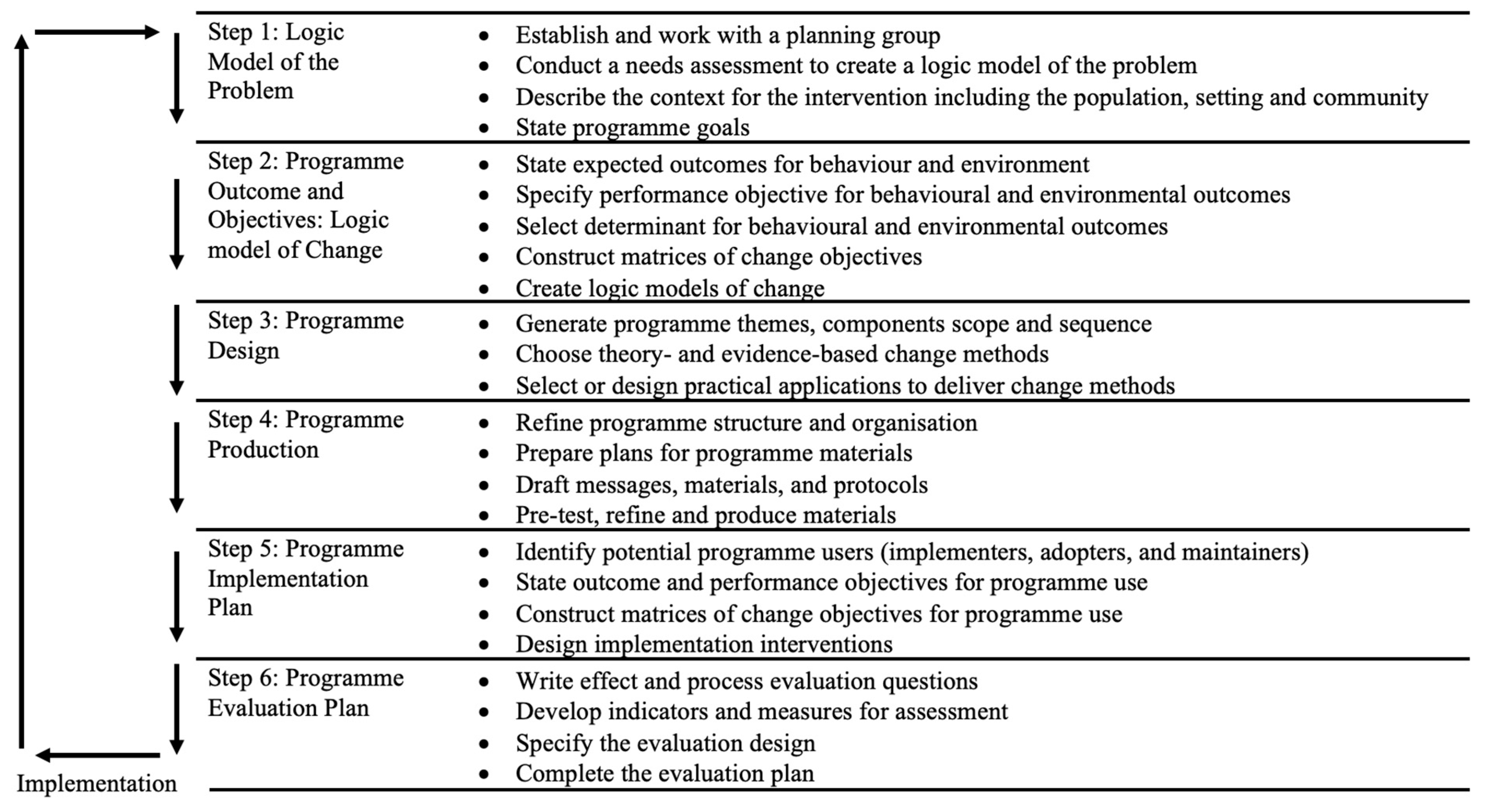

1.2. Introduction to Intervention Mapping

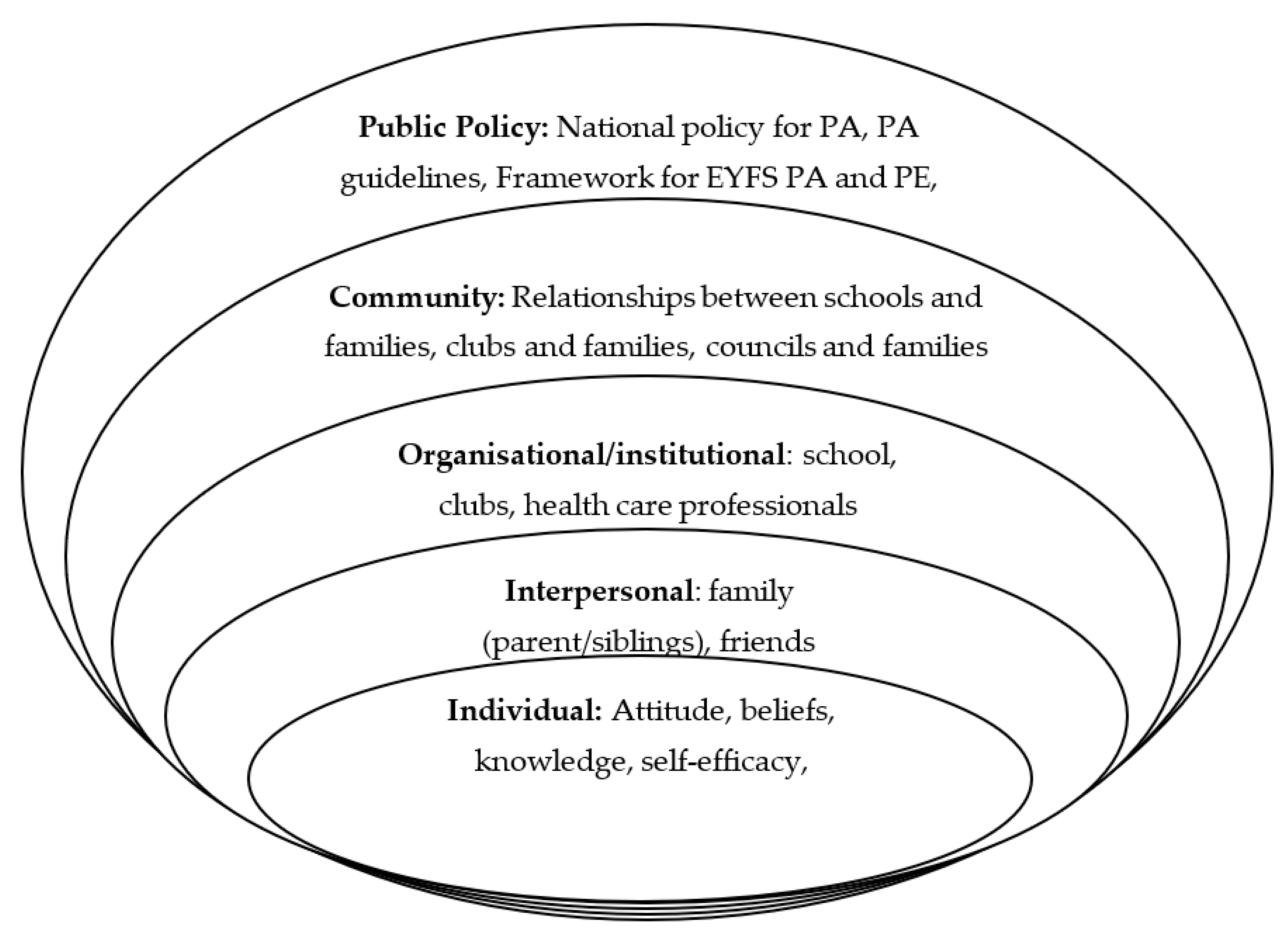

- Individual determinants are examined, including a child’s beliefs and attitude towards PA in addition to their enjoyment of activity.

- These determinants can be affected by a child’s immediate interpersonal environmental determinants, including members of a child’s family, their friends, and their peers, with knowledge and belief being shared between these groups.

- Organisational and institutional determinants are highly influential for children, especially in the early years. All children in England can experience the school setting, and therefore, it remains a key determinant influencing children’s choices and behaviours. A sense of community can help to foster better health behaviours. Stronger relationships between parents and schools, in addition to efforts by local authorities, can determine the health of a community.

- The highest-level determinant is public policy. When this determinant is considered, examining the policy for early PA and PE, in addition to dissemination of policy and statutory training of practitioners are key determinants. It is therefore important that programmes of intervention focus beyond the end recipient and includes key stakeholders.

1.3. This Research

2. Methods and Results—Six Steps

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Step 1: Logic Model of the Problem

2.2.1. Task 1.1: Establish the Planning Group

Planning Group Protocol and Involvement

2.2.2. Task 1.2: Needs Assessment and Logic Model of the Problem

2.2.3. Task 1.3: Programme Context, Population, Community, and Setting

2.2.4. Task 1.4: Broad Programme Goals

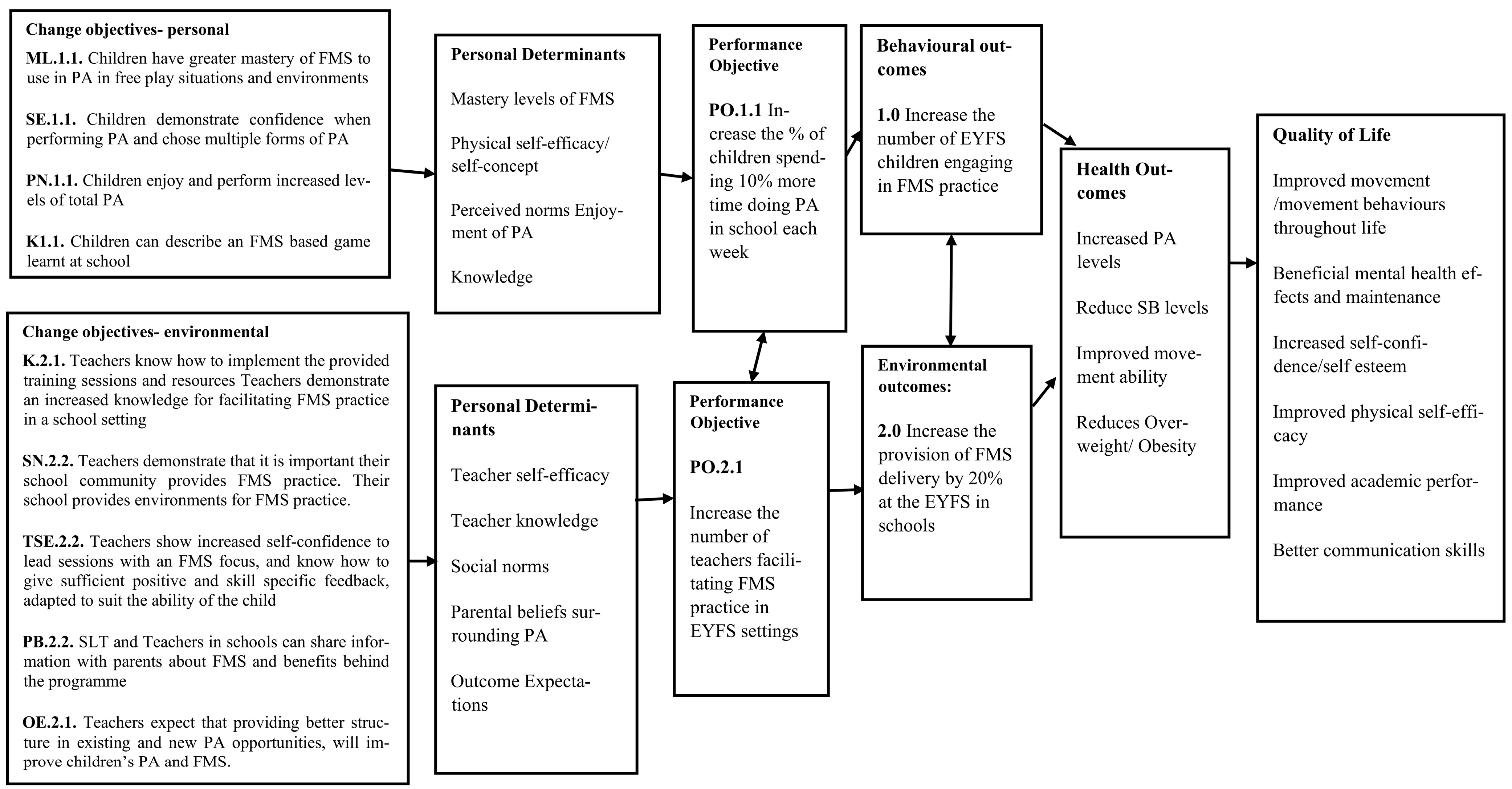

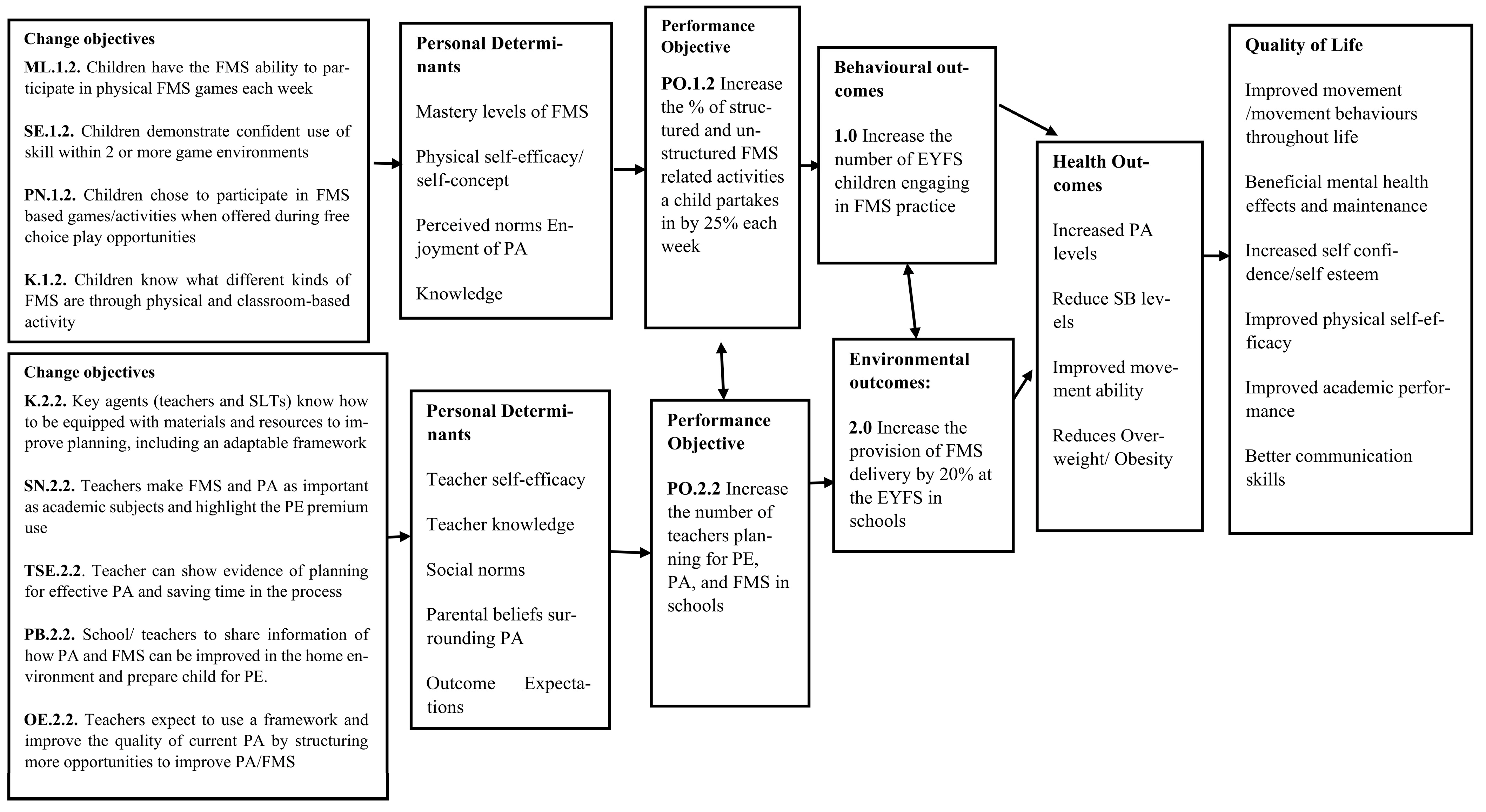

2.3. Step 2: Programme Outcomes and Objectives—The Logic Model of Change

2.3.1. Task 2.1: Expected Outcomes for Behaviour and the Environment

- Behavioural: 1.0 Increase the number of EYFS children engaging in FMS practice at school.

- Environmental: 2.0 Increase the provision of FMS delivery by 20% at the EYFS in schools.

2.3.2. Task 2.2: Performance Objectives for Behavioural and Environmental Outcomes

- 1.1. Increase the percentage of children spending 10 % more time doing PA in school each week

- 1.2. Increase the percentage of the structured and unstructured FMS-related activities a child partakes in each week by 25%

- 1.3. Increase the number of goals set for children’s FMS and PA performance by two each term

- 2.1. Increase the number of teachers facilitating FMS practice in EYFS settings

- 2.2. Increase the number of teachers planning for PE, PA, and FMS in schools

- 2.3. Increase the number of teachers aware of the benefits of providing EYFS children with PA opportunities

2.3.3. Task 2.3: Determinants for Behavioural and Environmental Outcomes

2.3.4. Task 2.4: Create Matrices of Change

2.3.5. Task 2.5: Logic Models of Change

2.4. Step 3: Programme Design

2.4.1. Task 3.1: Programme Themes, Components, Scope, and Sequence

2.4.2. Task 3.2: Theory and Evidence-Based Change Methods Chosen

2.4.3. Task 3.3: Practical Applications to Achieve Change in Intervention

2.5. Step 4: Programme Production

2.5.1. Task 4.1: Refine Programme Structure and Organisation

2.5.2. Task 4.2: Prepare Plans for Programme Materials

2.5.3. Task 4.3: Draft Message, Materials, and Protocols

2.5.4. Task 4.4: Produce, Pre-Test, and Refine Materials

2.6. Step 5: Programme Implementation Plan

2.6.1. Task 5.1: Identify Potential Adopters of Implementation for the Programme

- Implementers: Local authorities, delivery partners

- Adopters: Teachers, School senior leadership teams (SLT)

- Maintainers: Local authorities, delivery partners, teachers, School SLT

2.6.2. Task 5.2: State Outcomes and Performance Objectives for Programme Use

2.6.3. Task 5.3: Create Matrices of Change Objectives for Programme Use

2.6.4. Task 5.4: Design Implementation Interventions

2.7. Step 6: Programme Evaluation Plan

2.7.1. Task 6.1: Process and Effect Evaluation Questions

Effect Questions

- Has the programme improved children’s physical self-efficacy and academic performance?

- How much does the PA level and FMS mastery of the children completing the programme change from pre- to post-intervention?

- What was the impact of the programme on teachers’ knowledge and self-efficacy to teach and plan for FMS at the EYFS?

- What was the impact on the children’s knowledge and enjoyment of FMS?

- What was the structure of FMS delivery like in the participating schools before the intervention?

Process Questions

- What parts of the intervention worked well, and why? What did not work as well regarding the implementation, and why?

- What elements of the interventions have been sustained post-intervention?

- What aided dissemination and adoption of the programme?

- How often are teachers planning and using the framework in schools?

- If schools continue to use the programme, why?

- Have the participants (children) enjoyed the delivery of the intervention in schools?

2.7.2. Task 6.2: Indicators and Measures for Assessment, Task 6.3: Evaluation Methods, and Task 6.4: Evaluation Execution

- Card sort activities (Figures S4 and S5, Supplementary Materials)

- Surveys

- Interviews

- Observations

- Device-based measures (accelerometery)

3. Discussion and Summary

- What is the problem?

- What can be changed?

- How can it be changed?

- What is the design of change?

- Who needs to be involved in change and how?

- How can change be evaluated?

3.1. What Is the Problem?

3.2. What Can Be Changed?

3.3. How Can It Be Changed?

3.4. What Is the Design of Change?

3.5. Who Needs to Be Involved in Change and How?

- Parents—although parents have no direct role to play within the current intervention and its delivery, they can enhance the success and long-term outcomes achieved during the intervention period by engaging with the resources provided to them during the intervention. Engaging directly with parents is at the discretion of each individual school, and as with all interventions, it will have varying degrees of success. Despite this, communication with parents and the role they can play should be considered to be critical, especially in future work.

- School SLT—these key stakeholders must agree that using the intervention, training their staff, and use of the framework intervention is sustainable and worthwhile within their school.

- Local authorities—they are key partners in the implementing the programme in schools. Without local authorities, there is no initial platform to deliver and communicate the intervention from. Their influence on schools within the local authority should be key in ensuring sufficient and successful intervention uptake. In the long-term, which is dependent on intervention success and stakeholder opinion, local authorities could stipulate a mandatory need for the intervention in schools at the EYFS level.

- Delivery partners—they are key players within the local authority set-up, as they provide the training sessions for the intervention to teachers. They should support schools and teachers beyond the training, ensuring successful implementation within school environments.

- Public—policy makers at the government level represent the highest and possibly most influential level this intervention could reach: affecting public policy. The requirement for a statutory FMS intervention or improved framework at the EYFS could be pivotal to ensuring healthier and more active lifestyles for children from an early age. This programme could be delivered locally but be evaluated at a national level, much in the way children are assessed in literacy and maths skills.

3.6. How Can Change Be Evaluated?

- Environmental outcome: teachers planning to teach FMS

- Behavioural outcome: children practicing FMS

- Determinants: improving teachers, parents, and children’s knowledge of FMS, increasing the self-efficacy of the teachers to deliver FMS content/activity in school settings, providing children with an enjoyable intervention/FMS practice

- The completeness of delivery: was the programme delivered as intended with all its elements, and if not, why?

- Continuation of the intervention: once implemented in the school setting, was it continued successfully and appreciated by the adopters, maintainers, and users of the programme?

- Participant exposure: did the participants of the intervention receive the appropriate dose of the intervention?

3.7. Strengths and Limitations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Engel, A.C.; Broderick, C.R.; van Doorn, N.; Hardy, L.L.; Parmenter, B.J. Exploring the Relationship Between Fundamental Motor Skill Interventions and Physical Activity Levels in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1845–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, S.W.; Webster, E.K.; Getchell, N.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; Robinson, L.E. Relationship Between Fundamental Motor Skill Competence and Physical Activity During Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Kinesiol. Rev. 2015, 4, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallahue, D.L.; Ozmun, J.C.; Goodway, J.D. Understanding Motor Development: Infants, Children, Adolescents, Adults, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola, T.; Yli-Piipari, S.; Huotari, P.; Watt, A.; Liukkonen, J. Fundamental movement skills and physical fitness as predictors of physical activity: A 6-year follow-up study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2016, 26, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bremer, E.; Cairney, J. Fundamental Movement Skills and Health-Related Outcomes: A Narrative Review of Longitudinal and Intervention Studies Targeting Typically Developing Children. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2018, 12, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, L.M.; Webster, E.K.; Hulteen, R.M.; De Meester, A.; Valentini, N.C.; Lenoir, M.; Pesce, C.; Getchell, N.; Lopes, V.P.; Robinson, L.E.; et al. Through the Looking Glass: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Evidence, Providing New Insight for Motor Competence and Health. Sports Med. 2021, 52, 875–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.; Azevedo, L.; Wright, M.; Innerd, A.L. The Effectiveness of Fundamental Movement Skill Interventions on Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity Levels in 5- to 11-Year-Old Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2021, 52, 1067–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, S.W.; Robinson, L.E.; Wilson, A.E.; Lucas, W.A. Getting the fundamentals of movement: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of motor skill interventions in children. Child Care Health Dev. 2012, 38, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.J.; Barnett, L.M.; Cliff, D.P.; Okely, A.D.; Scott, H.A.; Cohen, K.E.; Lubans, D.R. Fundamental Movement Skill Interventions in Youth: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2013, 132, e1361–e1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Capelle, A.; Broderick, C.R.; van Doorn, N.; Ward, R.E.; Parmenter, B.J. Interventions to improve fundamental motor skills in pre-school aged children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, K.; Leeger-Aschmann, C.S.; Monn, N.D.; Radtke, T.; Ott, L.V.; Rebholz, C.E.; Cruz, S.; Gerber, N.; Schmutz, E.A.; Puder, J.J.; et al. Interventions to Promote Fundamental Movement Skills in Childcare and Kindergarten: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 2045–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartholomew-Eldredge, L.; Markham, C.; Ruiter, R.; Fernandez, M.; Kok, G. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dobell, A.; Pringle, A.; Faghy, M.A.; Roscoe, C.M.P. Educators Perspectives on the Value of Physical Education, Physical Activity and Fundamental Movement Skills for Early Years Foundation Stage Children in England. Children 2021, 8, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly-Smith, A.; Quarmby, T.; Archbold, V.S.J.; Corrigan, N.; Wilson, D.; Resaland, G.K.; Bartholomew, J.B.; Singh, A.; Tjomsland, H.E.; Sherar, L.B.; et al. Using a multi-stakeholder experience-based design process to co-develop the Creating Active Schools Framework. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goss, H.R.; Shearer, C.; Knowles, Z.R.; Boddy, L.M.; Durden-Myers, E.J.; Foweather, L. Stakeholder perceptions of physical literacy assessment in primary school children. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2021, 27, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Hogan, M.J.; Eyre, E.L.; Lander, N.; Barnett, L.M.; Duncan, M.J. Using Collective Intelligence to identify barriers to implementing and sustaining effective Fundamental Movement Skill interventions: A rationale and application example. J. Sports Sci. 2020, 39, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Hogan, M.J.; Eyre, E.L.J.; Lander, N.; Barnett, L.M.; Duncan, M.J. Enhancing the implementation and sustainability of fundamental movement skill interventions in the UK and Ireland: Lessons from collective intelligence engagement with stakeholders. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, D.S.; Ollis, S.; Thomas, N.E.; Baker, J.S. Physical Activity Behaviour: An Overview of Current and Emergent Theoretical Practices. J. Obes. 2012, 2012, 546459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Langford, R.; Jago, R.; White, J.; Moore, L.; Papadaki, A.; Hollingworth, W.; Metcalfe, C.; Ward, D.; Campbell, R.; Wells, S.; et al. A physical activity, nutrition and oral health intervention in nursery settings: Process evaluation of the NAP SACC UK feasibility cluster RCT. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pringle, A.; Kime, N.; Lozano-Sufrategui, L.; Zwolinsky, S. Evaluating Interventions. In The Routledge International Encyclopedia of Sport and Exercise Psychology: Volume 2: Applied and Practical Measures; Hackfort, D., Schinke, R.J., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Cools, W.; De Martelaer, K.; Samaey, C.; Andries, C. Fundamental movement skill performance of preschool children in relation to family context. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Guerrero, M.D.; Vanderloo, L.M.; Barbeau, K.; Birken, C.S.; Chaput, J.-P.; Faulkner, G.; Janssen, I.; Madigan, S.; Mâsse, L.C.; et al. Development of a consensus statement on the role of the family in the physical activity, sedentary, and sleep behaviours of children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi-Walker, L.J.; Duncan, M.; Tallis, J.; Eyre, E. Fundamental Motor Skills of Children in Deprived Areas of England: A Focus on Age, Gender and Ethnicity. Children 2018, 5, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dobell, A.; Pringle, A.; Faghy, M.A.; Roscoe, C.M.P. Fundamental Movement Skills and Accelerometer-Measured Physical Activity Levels during Early Childhood: A Systematic Review. Children 2020, 7, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyre, E.; Duncan, M.; Smith, E.C.; Matyka, K.A. Objectively measured patterns of physical activity in primary school children in Coventry: The influence of ethnicity. Diabet. Med. 2013, 30, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyre, E.L.; Adeyemi, L.J.; Cook, K.; Noon, M.; Tallis, J.; Duncan, M. Barriers and Facilitators to Physical Activity and FMS in Children Living in Deprived Areas in the UK: Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, C.M.P.; James, R.S.; Duncan, M.J. Accelerometer-based physical activity levels, fundamental movement skills and weight status in British preschool children from a deprived area. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2019, 178, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhao, M.; Han, X.; Che, L.; Qi, C.; Ma, X.; Wang, S. The relative age effect and gender difference on fundamental motor skills in preschool children aged 4–5 years. Early Child Dev. Care 2022, 193, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, E.S.; Tucker, P.; Burke, S.M.; Carron, A.V. Effectiveness of Physical Activity Interventions for Preschoolers: A Meta-Analysis. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2013, 84, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sport England Active Lives Children and Young People Survey Academic Year 2019/20. 2021. Available online: https://sportengland-production-files.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2021-01/Active%20Lives%20Children%20Survey%20Academic%20Year%2019-20%20report.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2021).

- Department for Education Guidance: PE and Sport Premium for Primary Schools. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/pe-and-sport-premium-for-primary-schools#how-to-use-the-pe-and-sport-premium (accessed on 3 September 2021).

- Lawless, W.; Borlase-Bune, M.; Fleet, M. The primary PE and sport premium from a staff perspective. Education 2019, 48, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, C.M.P.; James, R.S.; Duncan, M.J. Preschool staff and parents’ perceptions of preschool children’s physical activity and fundamental movement skills from an area of high deprivation: A qualitative study. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2017, 9, 619–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M.J.; Foweather, L.; Bardid, F.; Barnett, A.L.; Rudd, J.; O’brien, W.; Foulkes, J.D.; Roscoe, C.; Issartel, J.; Stratton, G.; et al. Motor Competence Among Children in the United Kingdom and Ireland: An Expert Statement on Behalf of the International Motor Development Research Consortium. J. Mot. Learn. Dev. 2022, 10, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, L.K.; Parcel, G.S.; Kok, G. Intervention Mapping: A Process for Developing Theory and Evidence-Based Health Education Programs. Health Educ. Behav. 1998, 25, 545–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.E.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Markham, C.M.; Kok, G. Intervention Mapping: Theory- and Evidence-Based Health Promotion Program Planning: Perspective and Examples. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979; ISBN 978-0-674-22456-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, C.M.; Ward, D.S.; Vaughn, A.; Neelon, S.E.B.; Vidal, L.J.L.; Omar, S.; Brouwer, R.J.N.; Østbye, T. Application of the Intervention Mapping protocol to develop Keys, a family child care home intervention to prevent early childhood obesity. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taylor, N.J.; Sahota, P.; Sargent, J.; Barber, S.; Loach, J.; Louch, G.; Wright, J. Using intervention mapping to develop a culturally appropriate intervention to prevent childhood obesity: The HAPPY (Healthy and Active Parenting Programme for Early Years) study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Verbestel, V.; De Henauw, S.; Maes, L.; Haerens, L.; Mårild, S.; Eiben, G.; Lissner, L.; Moreno, L.A.; Frauca, N.L.; Barba, G.; et al. Using the intervention mapping protocol to develop a community-based intervention for the prevention of childhood obesity in a multi-centre European project: The IDEFICS intervention. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’connor, A.; Blewitt, C.; Nolan, A.; Skouteris, H. Using Intervention Mapping for child development and wellbeing programs in early childhood education and care settings. Eval. Program Plan. 2018, 68, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew-Eldredge, L.K. Intervention Mapping Designing Theory-Based Evidence-Based Programs Workbook 2017; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Noonan, R.J.; Boddy, L.M.; Fairclough, S.J.; Knowles, Z.R. Write, draw, show, and tell: A child-centred dual methodology to explore perceptions of out-of-school physical activity. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- NICE 1 Recommendations | Behaviour Change: Individual Approaches | Guidance | NICE. 2014. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph49/chapter/1-recommendations#recommendation-9-deliver-very-brief-brief-extended-brief-and-high-intensity-behaviour-change (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Peers, C.; Issartel, J.; Behan, S.; O’Connor, N.; Belton, S. Movement competence: Association with physical self-efficacy and physical activity. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2020, 70, 102582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, J.D.; Knowles, Z.; Fairclough, S.J.; Stratton, G.; O’dwyer, M.; Ridgers, N.D.; Foweather, L. Effect of a 6-Week Active Play Intervention on Fundamental Movement Skill Competence of Preschool Children. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2017, 124, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, B.; Liu, J.; Ying, B. Physical education interventions improve the fundamental movement skills in kindergarten: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e46721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griggs, G. For sale—Primary physical education. £20 per hour or nearest offer. Education 2010, 38, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, G.; Gottlieb, N.H.; Peters, G.-J.Y.; Mullen, P.D.; Parcel, G.S.; Ruiter, R.A.; Fernández, M.E.; Markham, C.; Bartholomew, L.K. A taxonomy of behaviour change methods: An Intervention Mapping approach. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Vogt, T.M.; Boles, S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rutherford, Z.; Zwolinsky, S.; Kime, N.; Pringle, A. A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of CARE (Cancer and Rehabilitation Exercise): A Physical Activity and Health Intervention, Delivered in a Community Football Trust. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colella, D.; Morano, M.; Bortoli, L.; Robazza, C. A PHYSICAL SELF-EFFICACY SCALE FOR CHILDREN. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2008, 36, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, K.; Meehan, C. Walking the talk? Teachers’ and early years’ practitioners’ perceptions and confidence in delivering the UK Physical Activity Guidelines within the curriculum for young children. Early Child Dev. Care 2017, 189, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morano, M.; Rutigliano, I.; Rago, A.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M.; Campanozzi, A. A multicomponent, school-initiated obesity intervention to promote healthy lifestyles in children. Nutrition 2016, 32, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronk, N.P.; Faghy, M.A. Causal systems mapping to promote healthy living for pandemic preparedness: A call to action for global public health. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sport England Local Delivery Pilots. Available online: https://www.sportengland.org/funds-and-campaigns/local-delivery (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- GOV. UK School Starting Age. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/schools-admissions/school-starting-age#:~:text=Your%20child%20must%20start%20full,school%20age%20on%20that%20date (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Xiang, P.; McBride, R.; Bruene, A. Relations of Parents’ Beliefs to Children’s Motivation in an Elementary Physical Education Running Program. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2003, 22, 410–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, N.; Johnson, S.L.; Boles, R.E.; Bellows, L.L. Social-ecological correlates of fundamental movement skills in young children. J. Sport Health Sci. 2019, 8, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS Digital National Child Measurement Programme, England 2020/21 School Year. 2021. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/national-child-measurement-programme/2020-21-school-year# (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Hulteen, R.M.; Morgan, P.J.; Barnett, L.M.; Stodden, D.F.; Lubans, D.R. Development of Foundational Movement Skills: A Conceptual Model for Physical Activity Across the Lifespan. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1533–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stodden, D.F.; Goodway, J.D.; Langendorfer, S.J.; Roberton, M.A.; Rudisill, M.E.; Garcia, C.; Garcia, L.E. A developmental perspective on the role of motor skill competence in physical activity: An emergent relationship. Quest 2008, 60, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, J.W.; Cossette, S.; Alderson, M. Autonomy-supportive intervention: An evolutionary concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 1254–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lander, N.; Eather, N.; Morgan, P.J.; Salmon, J.; Barnett, L.M. Characteristics of Teacher Training in School-Based Physical Education Interventions to Improve Fundamental Movement Skills and/or Physical Activity: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 135–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foweather, L.; McWhannell, N.; Henaghan, J.; Lees, A.; Stratton, G.; Batterham, A.M. Effect of a 9-Wk. after-School Multiskills Club on Fundamental Movement Skill Proficiency in 8- to 9-Yr.-Old Children: An Exploratory Trial. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2008, 106, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Coaching Learning, T. The STEP Model Explained—UK Coaching. Available online: http://www.ukcoaching.org/Resources/Topics/Videos/Subscription/The-STEP-Model-Explained (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Crotti, M.; Rudd, J.R.; Roberts, S.; Boddy, L.M.; Davies, K.F.; O’callaghan, L.; Utesch, T.; Foweather, L. Effect of Linear and Nonlinear Pedagogy Physical Education Interventions on Children’s Physical Activity: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial (SAMPLE-PE). Children 2021, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonell, C.; Fletcher, A.; Morton, M.; Lorenc, T.; Moore, L. Realist randomised controlled trials: A new approach to evaluating complex public health interventions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 2299–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Problem | Low FMS Competency in the Early Years |

|---|---|

| Whose problem is it? | Children, parents, teachers, school senior leadership, community provision, government |

| Who is the problem affecting? | Young children |

| What behaviours are causing or are related to the problem? | Sedentary lifestyles, poor-quality PA, lack of planning and training, lack of knowledge and time to enhance this |

| The environmental conditions causing or related to the problem | Reduced outdoor space, poor PA facilities, incorrect use of resources, lack of time for PA, lack of training for teachers |

| Determinants of these behaviours and environment | Underfunding in communities and schools, poverty, lack of practitioner knowledge of FMS, cultural norms associated with PA |

| Social Environment Asset Assessment | Information Environment Asset Assessment | Policy/Practice Environment Asset Assessment | Physical Environment Asset Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| a. Primary schools | a. School newsletters/bulletins | a. EYFS framework | a. School spaces |

| b. Community sports groups | b. Word of mouth | b. PE curriculum | b. Local community spaces/parks |

| c. Parent groups | c. Local authority communications | c. CMO activity guidelines | c. Local sports teams/leisure facilities |

| d. Youth groups/after-school clubs | d. Social media channels | d. Teacher training for early years | d. Home environments |

| Intervention Components: | Intervention Scope: |

|---|---|

| Intervention one: | Programme delivery by delivery partners to teachers: |

Teacher training

|

|

| Intervention two: | Programme delivery by teachers in the school setting: |

Framework documentation

|

|

| Determinants of the Problem | Behaviour Change Methods | Parameters | Practical Applications and How Delivered |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | |||

| The social norm is for children to be sedentary | Change the perceived norms: Belief selection Role modelling | Knowledge of children’s existing beliefs and simple messaging for children are required Attention shown to role modelling, self-efficacy to be active/use skills | Promotion in school settings (posters, children’s work on display), have activity-based lessons Role modelling by teachers to be active with the children and provide them with increased active opportunities |

| Children lack knowledge about their fundamental movement skills | Changes in knowledge: Active learning Individualisation | Time bounds of school and lesson time, information available to teachers Responds to each child’s needs | Framework activities: FMS-based and themed activities within school learning opportunities (practical and classroom-based) STEP model |

| Children lack mastery to perform good FMS and increase their PA | Increase children’s skills: Active learning Tailoring | Skills of teachers to improve child mastery, time in school Matching children’s existing skill levels | Framework activities: practical activities and planned sessions (organisation) Teacher-planned sessions using STEP |

| Children lack self-efficacy in their movement | Increase support and goal setting: Feedback | Needs to be individual to the child and specific to their skills | Teacher to work one-on-one with the children in class Set goals with children each term |

| Environmental | |||

| Teachers lack self-efficacy and knowledge to teach and provide FMS in education setting | Increase teachers’ skills: Active learning Changes in knowledge: Individualisation Feedback | Existing skills and knowledge, information available in training sessions Responding to each teacher’s needs Specific to the teacher and their school at a given time | Provide interactive training content for teachers to engage with (multiple sessions) Framework provides opportunity to personalise session delivery to each teacher’s skills Delivery partner to review progression with framework each term |

| Parents’ lack of awareness to help children practice skills taught at school at home | Increase awareness: Persuasive communication Facilitation | Relevant messages to the parents and their children Surprise and repetition Identifying barriers to participation | Advertising the intervention happening in school, send home progress in monthly newsletter Use as homework tasks for children to do at home with their parents |

| School settings and environmental agents lack knowledge to provide FMS education at the EYFS and do not know how it links to PA | Changes in knowledge: Active learning Tailoring | Time available to provide new knowledge Matching to the culture of school and/or SES | Videos within training for teachers to use widely in school Train teachers to match the needs of children and school (number of children, skills of children, etc.) |

| Teachers and schools feel it is the social norm not to be aware of FMS education and practice for EYFS children | Change the perceived norms: Belief selection | Knowledge of teacher’s/school’s existing beliefs of PA and FMS | Role modelling (delivery partners) Testimonials of other schools using the intervention successfully |

| Broad Practical Application and Basic Change Method | Detailed Change Method | Detailed Practical Application | Population, Context, Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Framework and increasing skills (active learning)—children | Guided practice—repeating behaviours several times with feedback Setting graded tasks—increasing the difficulty of task as behaviour improves Stimulus control—adding more cues for healthier behaviours | Practical session delivery from the framework Using the STEP model to grade the tasks in PA sessions Adding more cues to be active within school day | Population: Children Context: In-school PE lessons/active times Parameters: Different sessions can be planned from the framework, time available to deliver the sessions |

| Framework and increasing knowledge (active learning)—children | Using imagery: using artefacts with a similar appearance to the subject Chunking—stimulus patterns to make parts of a movement a whole | Using images of skills within classroom-based activities or images so that children begin to associate with the skills (e.g., animals) Splitting skills down by component parts through the activities performed | Population: Children Context: In-school classroom lessons Parameters: Familiarity of the images/activity to the children |

| One-to-one with children and increasing support for self-efficacy | Goal setting—prompting planning to reach goal-directed behaviours Providing cues—consistent cues throughout sessions | Teachers set goals with children—example goals within the framework Children are given opportunities to develop their own cues to use when performing skills | Population: Children Context: In-school PE lessons/active times Parameters: Children best to develop their own cues for performance |

| Training and increasing skills (active learning)/increasing self-efficacy—teachers | Guided practice—repeating behaviours several times with feedback Mobilising social support—instrumental and emotional social support for teachers Planning coping responses—identifying barriers and ways to overcome them | Teachers rehearse using framework and gain feedback from delivery partner during and after delivery using own self-evaluation Teachers identify barriers within their classes within training and formulate plans to overcome these | Population: Teachers Context: Training session and regular contact with delivery partner Parameters: How much support a delivery partner can give |

| Training and changes in knowledge—teachers | Advance organisers—presenting an overview of the material Discussion—encourage debate over a topic Using imagery—using artefacts with a similar appearance to the subject | Present an overview of the framework within the training for the teachers (over three sessions) Hold discussion within training sessions to discuss ideas proposed Videos demonstrating how skills can be performed, videos of activities with children | Population: Teachers (and children—imagery) Context: Training session Parameters: Length of training sessions, available resources, prior knowledge for discussions |

| Changing social norms of schools | Public commitment—pledging to engage in healthier behaviours Cultural similarity Provide contingent rewards—praising and encouraging behaviours | School publicly says they will be running the programme through newsletters, school displays, within reports Using messages from other schools (preferably local) to show the success of a programme School openly praises healthier behaviours with rewards (more time to be active) | Population: Whole school community Context: Delivery in school Parameters: sociocultural characteristics of specific schools, praise must only follow the specific behaviour |

| Parent packs and increasing awareness: persuasive communication | Consciousness raising—providing information and feedback Framing—gain-framing messages and the advantages of healthy changes | Homework tasks—provide information about school tasks and reports- feedback for parents to act on Use reports to demonstrate the benefits; parent packs of information and benefits to child and family | Population: Parents Context: Actions performed at home Parameters: Gain frames to be used rather than loss frames to use positive messages; self-efficacy of parent and child to be considered |

| Environmental Agent Intervention | Individual Intervention |

|---|---|

| What (intervention): Teacher training sessions on FMS, PA, health, and framework delivery | What (intervention): Adaptable framework delivery in schools |

| Who: Delivery partners (facilitators) and teachers (target group/participants) | Who: Teachers (facilitators) and children (target group) |

| Where (setting): In-school settings or local authority settings | Where (setting): In schools, in the EYFS |

| When (sequence): Before autumn/winter, spring, and summer term at school (in England) = three times per year | When (sequence): Delivery of the framework across a whole school term |

| How much (scope): three training sessions per training block | How much (scope): Delivery of an intervention application at least three times per week |

| How often (scope): three times per year | How often (scope): Designed to be used for each term of school |

| Interpersonal delivery channels: Dissemination: Delivery partner leader to lead the training (with peer leaders) | Interpersonal delivery channels: Awareness: Teachers discussing with parents, health visitors promoting the intervention to schools, volunteer parents who have previously observed success in the programme Dissemination: Teachers working with children, children working with peers, parents aiding children, volunteer parents |

| Mediated delivery channels: Dissemination: Written print (framework document), videos of training, social media groups (network of teachers to discuss ideas), flip charts, media presentations, recorded training session archives | Mediated delivery channels: Awareness: Using videos on social media (school) to promote the intervention, a website explaining the intervention to children and parents, school newsletters and displays within the school, written information sent to parents, texts/app messages sent from school to parents Dissemination: Printed materials with information, videos for children to watch, a website showing activities done at school and ones for at home, social media groups for parents to discuss their home activities |

| Programme Component | Description | Producers | Drafted in This Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Video of the intervention for schools | Video showing how the framework works in action. Images of the training and then of teachers delivering in school settings. Feedback/testimony of previous training experience by SLT and teachers. | Media experts (filming, production, etc.) | No |

| Newsletter promotions |

| Researchers to provide templates for schools to use in their own dissemination | No |

| Social media promotions |

| Social media experts/graphic designers | No |

| Websites about intervention |

| Website producers | No |

| Training sessions | Slides accompanied by verbal delivery from a delivery partner, practical practice environments, worksheets to complete during the sessions | Researchers design these materials/plans for delivery in partnership with a group of delivery partners | Yes (one session) |

| Framework booklet: Information about FMS | Section of booklet reiterating information delivered in the training for teachers to refer to and strengthen their knowledge while delivering the programme/intervention | Printing services, visual/graphic designers | Yes |

| Framework booklet: Planning practical activities | A section split by FMS domain that provides activities lasting 5–15 min. All activities must have a STEP adaptation example and list equipment needed, time taken, and outcomes from each activity; a planning section for teachers to plan the use of activities in extended PA/PE sessions; homework activities for children to do STEP model, guided practice | Printing services, visual/graphic designers, researchers designing activities | Yes |

| Framework booklet: Planning classroom activities | A section of examples of classroom-based activities that promote FMS or use stimulus to enhance children’s learning; suggested academic areas for activities, including homework activities. Imagery and stimulus cues | Printing services, visual/graphic designers, researchers designing activities | Yes |

| Framework booklet: Activity sheets | Training: sheets for teachers to complete related to the training content to help solidify learning and to make their own notes Framework: goal setting activity sheets for children to complete with their teacher each term to set goals about their FMS goals setting Other activity sheets related to other curricular areas that will combine the knowledge of FMS for children (maths, English, art, etc.) | Printing services, visual/graphic design, researchers designing activities | Yes (in framework) |

| Programme Application/Component | Pre-Test Objectives | Pre-Test Population | Pre-Test Procedure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Video advertising the intervention for schools | Improve awareness of FMS for teachers within training and to refer to within the framework | SLT and teachers | Send link of video to watch and provide feedback on (used in training) |

| Newsletter promotions | Teachers know how to share information about the FMS programme with parents Teacher can share class targets with whole school and demonstrate a community for FMS practice at school | Teachers and parents | Provide teachers with template newsletter excerpts and ask them to report the ease of editing and the interest reported by parents and staff when shared |

| Social media promotions | SLT and teachers can easily share information with parents about PA and FMS at home and the benefits of the programme | SLT, teachers, and parents | Schools share the social media posts with parents (on school Facebook/apps). Parents are then asked if they have heard about the intervention (to measure effectiveness) |

| Websites about intervention | Key agents (teachers and SLT) are equipped with materials and resources to deliver the framework | SLT, teachers | Teachers and SLT are asked to navigate the websites and report the ease of finding materials and information they wanted/needed |

| Training sessions | Teachers know how to implement the framework within their school setting Teachers have increased knowledge of FMS | Teachers | Conduct pilot sessions of the training with a group of EYFS teachers, with feedback opportunities for the training content |

| Framework booklet: Information about FMS | Teachers can explain why PA is important for child health and academic achievement | Teachers | Provide teachers who were trained in the pilot sessions with the booklet |

| Framework booklet: Planning practical activities | Teachers have increased self-confidence to lead FMS sessions with skill-specific adaptations Teacher can plan effectively for FMS Children engage in the FMS activities to improve their mastery and demonstrate higher confidence in their FMS | Teachers and children | Provide teachers who are trained in the pilot sessions with the booklet. Ask them to plan two practical sessions from the booklet to do with their classes and provide feedback on its ease of use to plan teacher sessions Children can give formative feedback at the end of the sessions (if they enjoyed them, if they were fun, etc.) |

| Framework booklet: Planning classroom activities | Teachers can use framework to allocate more FMS-based activities to improve PA/FMS Teachers make FMS and PA as important as other academic subjects Children know about different kinds of FMS and can describe an FMS game from school | Teachers and children | Provide teachers who are trained in the pilot sessions with the booklet. Teachers can plan to use classroom activities twice a week with their classes and provide feedback on the success in other curriculum areas Children are tasked with homework to do a game/activity at home with their parents to show what they have learnt/understood from the programme |

| Parent packs/information | SLT and teachers can easily share information with parents about PA and FMS at home | SLT, teachers, and parents | Teachers are asked to share the information packs with parents when homework is set for the children. Parents are asked if the information helped them to complete the homework with their children (Likert scale, e.g., helped a lot, somewhat helped, did not help nor hinder, did not help, very unhelpful) |

| Framework booklet: Activity sheets | Children are involved in setting PA and FMS goals and can begin to set their own goals Teacher can demonstrate the importance of FMS targets for children | Teachers and children | Provide teachers who are trained in the pilot sessions with the booklet. Teachers can plan to use the goal-setting sheets with the children once a term and provide feedback on its ease of use and suitability. |

| Outcome for programme dissemination/implementer (local authority) |

|---|

| 3.0 Increase the number of delivery partners delivering The FMS School Project training |

| PO.3.1 Increase the number of schools receiving The FMS School Project information |

| PO.3.2 Increase the number of local authorities using delivery partners for The FMS School Project training |

| PO.3.3 Increase the number of local authorities planning to use delivery partners for The FMS School Project training |

| Outcome for programme implementation and adoption (delivery partner) |

| 4.0 Increase the number of schools delivering The FMS School Project framework |

| PO.4.1 Increase the number of schools receiving The FMS School Project training |

| PO.4.2 Increase the number of schools planning to receive The FMS School Project training |

| PO.4.3 Increase the number of schools interested in using The FMS School Project training |

| Outcome for programme maintenance (teachers and school SLT) |

| 5.0 Increase the number of schools using The FMS School Project framework for more than one school year |

| PO.5.1 Increase the number of teachers evaluating The FMS School Project framework at the EYFS |

| PO.5.2 Increase the number of SLTs granting the appropriate funds for The FMS School Project |

| PO.5.3 Increase the number of schools providing the appropriate time for The FMS School Project framework |

| Outcome for programme maintenance (local authority and delivery partners) |

| 6.0 Increase the number of delivery partners delivering The FMS School Project training for more than one school year |

| PO.6.1 Increase the number of delivery partners/local authorities evaluating The FMS School Project training |

| PO.6.2 Increase the number of local authorities granting the appropriate funds for The FMS School Project training delivery |

| PO.6.3 Increase the number of local authorities providing the appropriate time for The FMS School Project training |

| Change Objectives | Theoretical Methods | Intervention Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Dissemination (of training) Disseminate information and benefits clearly about the programme to schools LAs know the scope, sequence, themes, and components of the programme and which delivery partner in LA will be appropriate LA can employ delivery partners and explain why it is normal to use them for this kind of intervention | Persuasive communication Tailoring Individualisation Persuasive communication Tailoring Persuasive communication Discussion | Local authority communication with schools (visits) Advertisement on social media, videos, newsletters, websites Written materials Website with information about intervention and for LA DPs to sign up LA advertising to existing members of staff; focus groups with staff to identify appropriate staff member roles |

| Adoption and implementation (of training) DPs know how to explain the scope, sequence, themes, and components of the programme to teachers and explain why it is good CPD DPs can explain the training and framework of the programme DPs can communicate with schools and SLT and make a case about programme delivery and training | Persuasive communication Individualisation Advance organisers Active learning Modelling Discussion Persuasive communication Tailoring | Local authority communication with schools (visits); advertisement in social media, videos, newsletters, and emails Written training materials Practical training for DPs Practical training for DPs Scenario practice (Communications as previously mentioned) |

| Maintenance (of framework) Teachers can demonstrate the evaluation methods of the programme to identify success and areas of improvement SLTs can explain how to grant the appropriate funds for the intervention and equipment from the PE premium SLT and teachers can explain and use time and timetabling effectively to allow for a whole school year of The FMS School Project | Participation Active learning Facilitation Facilitation Advance organisers Participation Persuasive communication Belief selection | Teacher uses evaluation materials provided in the framework Draft reports for SLT that teacher can populate with outcomes Information for SLT about the use of funding and PE premium use for programme (on paper and on a website) DP visits to schools to help plan funds for delivery SLT see the benefits of the programme within their schools DP visits schools to help plan time for delivery |

| Maintenance (of training) DP and LA know how to evaluate the delivery of the training programme LA can allocate funding for employing DP and the delivery of training LA can allow DPs appropriate time to plan, prepare, and deliver successful training | Participation Active learning Facilitation Participation Persuasive communication Individualisation Facilitation | DP/LA uses evaluation materials provided in the training Draft reports for LA to populate with outcomes LA see the benefits of the programme for schools Guidance documents for LA on allocations of money for delivery of DP and training; adjustments according to previous results (e.g., more or less funding) Guidance documents for LA on allocations for DP planning and delivery time of training |

| Variables | Indicators and Time Frame | Methods and Execution |

|---|---|---|

| Effect | ||

| Quality of life Physical self-efficacy Academic performance | One school term: Physical self-efficacy rated higher Improved academic performance | Questionnaire [52] Teacher assessment/observation |

| Health outcomes Better PA levels Better movement ability | One school year: Weekly PA increases Can complete more complex movement tasks | Accelerometry measurements Class-based assessment—reported in survey |

| Behavioural outcomes Practicing FMS Increasing PA levels with peers | One school term: Better FMS mastery Spends more time in moderate–vigorous PA | Observational assessments Accelerometry measurements |

| Environmental outcomes Teachers engaging with FMS teaching Structure for EYFS, FMS, and PE | One school term: Frequency of framework use Planning for sessions completed | Survey/tracking Survey/tracking (submission of evidence) |

| Determinants of change Knowledge (T) Self-efficacy (T) Enjoyment (C) Knowledge (C) | One school year: Can identify FMS domains and activities related to them Has confidence to use framework and plan sessions from it Can name an activity they enjoy completing related to the framework Shows knowledge of different FMS | Interview Interview Card sort Card sort |

| Process | ||

| Programme implementation Dissemination Adoption | Number of schools completing The FMS School Project Training Number of schools using The FMS School Project framework in practice for a term | Local authority survey of schools delivered to Survey of schools that have received training |

| Implementation Completeness Fidelity Continuation Programme users’ evaluation Programme users’ barriers | Three training sessions delivered Practical, classroom, and home activities used from framework in schools All elements in training are covered using designed materials One year of use in schools and LAs Enjoyment to deliver, ease to deliver Issues with delivery, barriers to use | Survey numbers from LA Tracking by teachers in schools Observation of training sessions School/LA survey Teachers/SLT/DP/LA—interviews, teacher card sort Teachers/SLT/DP/LA—interviews |

| Intervention exposure Participant exposure (use of materials) Participant evaluation | Number of times framework was delivered per week Child enjoyment, child-identified benefits/feelings | Survey/tracking Card sort |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dobell, A.P.; Faghy, M.A.; Pringle, A.; Roscoe, C.M.P. Improving Fundamental Movement Skills during Early Childhood: An Intervention Mapping Approach. Children 2023, 10, 1004. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061004

Dobell AP, Faghy MA, Pringle A, Roscoe CMP. Improving Fundamental Movement Skills during Early Childhood: An Intervention Mapping Approach. Children. 2023; 10(6):1004. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061004

Chicago/Turabian StyleDobell, Alexandra Patricia, Mark A. Faghy, Andy Pringle, and Clare M. P. Roscoe. 2023. "Improving Fundamental Movement Skills during Early Childhood: An Intervention Mapping Approach" Children 10, no. 6: 1004. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061004

APA StyleDobell, A. P., Faghy, M. A., Pringle, A., & Roscoe, C. M. P. (2023). Improving Fundamental Movement Skills during Early Childhood: An Intervention Mapping Approach. Children, 10(6), 1004. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061004