Social Acceptance in Physical Education and the Regular Classroom: Perceived Motor Competency and Frequency and Type of Sports Participation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Correlates of Social Acceptance in Different School Contexts

1.2. Perceived Physical Competence

1.3. Sports Participation

1.4. This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instrumentation

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

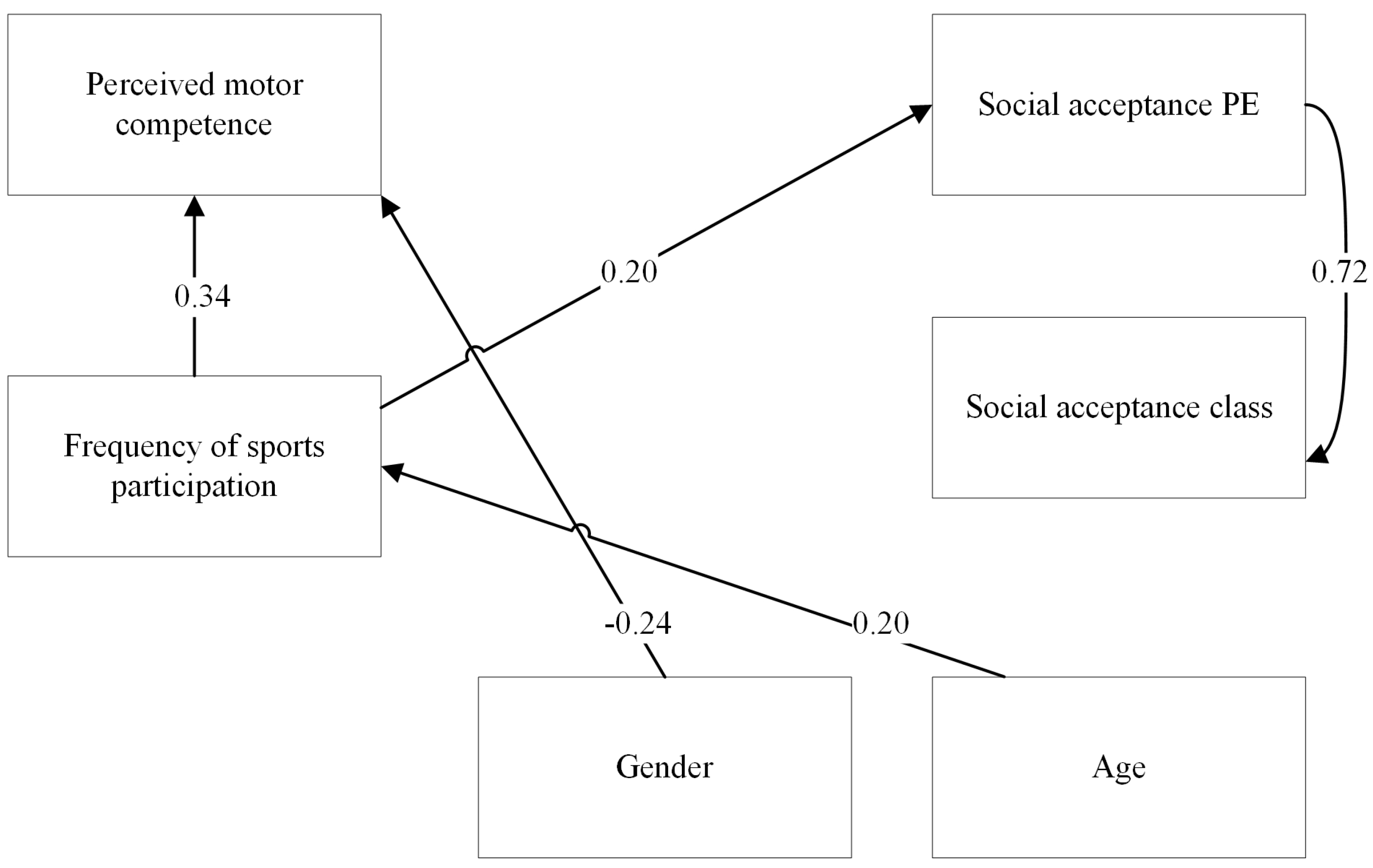

3.2. Overall Relations

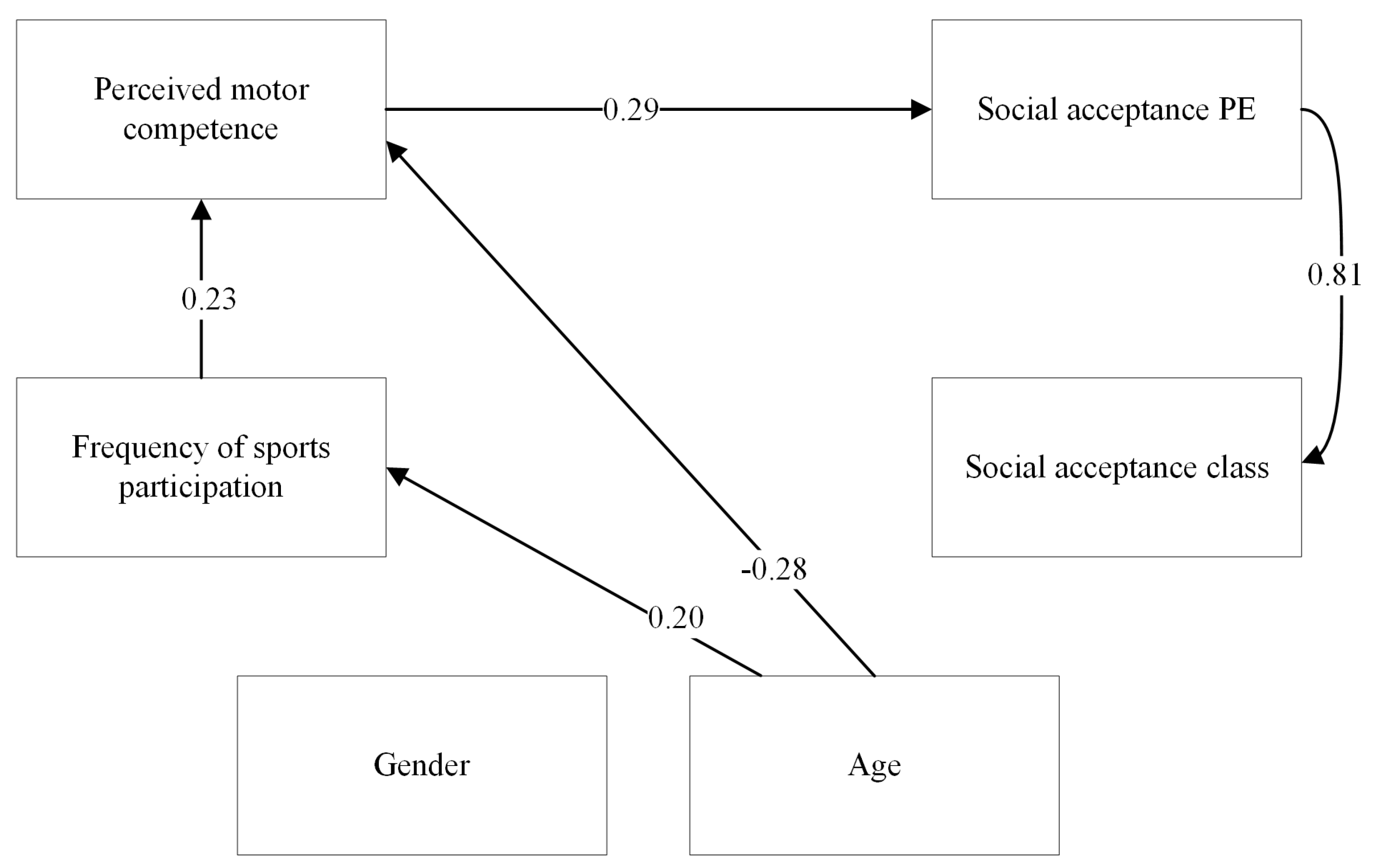

3.3. Relations Separated by Type of Sports

4. Discussion

4.1. Perceived Physical Competence

4.2. Sports Participation

4.3. Individual vs. Team Sport Players

4.4. Implications

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bukowski, W.M.; Laursen, B.P.; Rubin, K.H. Peer relations. Past, present and promise. In Handbook of Peer Interactions, Relationships, and Groups, 2nd ed.; Bukowski, W.M., Laursen, B.P., Rubin, K.H., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hollett, N.; Brock, S.J.; Cosgrove, B.; Grimes, J.R.; Hastie, P.; Wadsworth, D. ‘Involve me, and I learn’: Effects of social status on students’ physical activity, skill, and knowledge during group work. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2022, 28, 1025–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R. Physical Education and Sport in Schools: A Review of Benefits and Outcomes. J. Sch. Health 2006, 76, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciotto, C.M.; Gagnon, A.G. Promoting Social and Emotional Learning in Physical Education. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 2018, 89, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimminger, E.; Grimminger-Seidensticker, E. Sport motor competencies and the experience of social recognition among peers in physical education—A video-based study. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2013, 18, 506–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimminger, E.; Grimminger-Seidensticker, E. Getting into teams in physical education and exclusion processes among students. Pedagog. Int. J. 2014, 9, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.R.; Smith, A.L.; Theeboom, M. “That’s What Friends Are For”: Children’s and Teenagers’ Perceptions of Peer Relationships in the Sport Domain. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1996, 18, 347–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiner, D.L.; Godwin, J.; Dodge, K.A. Predicting Academic Achievement and Attainment: The Contribution of Early Academic Skills, Attention Difficulties, and Social Competence. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 45, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Krasnor, L. The Nature of Social Competence: A Theoretical Review. Soc. Dev. 1997, 6, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollett, N.; Brock, S.J.; Grimes, J.R.; Cosgrove, B. Is knowledge really power? Characteristics contributing to social status during group work in physical education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2019, 25, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilland, T.; Ridgers, N.; Stratton, G.; Knowles, Z.; Fairclough, S. Origins of perceived physical education ability and worth among English adolescents. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2016, 24, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, G.; Larsson, H. Exploring ‘what’ to learn in physical education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2012, 19, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz de Bustillo, M.C.; Martín, E. “El mapa de mi ciudad escolar”: Una guía para analizar la Convivencia en la escuela (My school city map: A guide to analyse the cohabitation in school). In Mejora de la Convivencia y Programas Encaminados a la Prevención e Intervención del Acoso Escolar (Improvement of Cohabitation and Programmesfor Bullyng Prevention and Intervention); Gázquez, J.J., Pérez, M.C., Cangas, A.J., Yuste, N., Eds.; Grupo Editorial Universitario: Granada, Spain, 2007; pp. 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, S.M.; Buhs, E.S.; Warnes, E.D. Childhood peer relationships in context. J. Sch. Psychol. 2003, 41, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, E. The influence of diverse interaction contexts on students’ sociometric status. Span. J. Psychol. 2011, 14, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevan, I.; Barnett, L.M. Considerations Related to the Definition, Measurement and Analysis of Perceived Motor Competence. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 2685–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.A.; Kless, S.J.; Adler, P. Socialization to Gender Roles: Popularity among Elementary School Boys and Girls. Sociol. Educ. 1992, 65, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, M.A.; Dummer, G.M. The Role of Sports as a Social Status Determinant for Children. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1992, 63, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, M.; Gill, D. Perceived physical competence and body image as predictors of perceived peer acceptance in adolescents. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 15, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.L.; Ullrich-French, S.; Walker, E.; Hurley, K.S. Peer relationship profiles and motivation in youth sport. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2006, 28, 362–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.R.; Duncan, S.C. The Relationship between Physical Competence and Peer Acceptance in Tie Context of Children’s Sports Participation. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1992, 14, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.C.; Dunn, J.G.; Bayduza, A. Perceived Athletic Competence, Sociometric Status, and Loneliness in Elementary School Children. J. Sport Behav. 2007, 30, 249–269. [Google Scholar]

- Stodden, D.F.; Goodway, J.D.; Langendorfer, S.J.; Roberton, M.A.; Rudisill, M.E.; Garcia, C.; Garcia, L.E. A developmental perspective on the role of motor skill competence in physical activity: An emergent relationship. Quest 2008, 60, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L.M.; Morgan, P.J.; Van Beurden, E.; Beard, J.R. Perceived sports competence mediates the relationship between childhood motor skill proficiency and adolescent physical activity and fitness: A longitudinal assessment. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L.M.; Webster, E.K.; Hulteen, R.M.; De Meester, A.; Valentini, N.C.; Lenoir, M.; Pesce, C.; Getchell, N.; Lopes, V.P.; Robinson, L.E.; et al. Through the looking glass: A systematic review of longitudinal evidence, providing new insight for motor competence and health. Sports Med. 2021, 52, 875–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Burns, R.D. Gross motor skills and school day physical activity: Mediating effect of perceived competence. J. Mot. Learn. Dev. 2018, 6, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Thomas, K.T.; Chen, Y.L. The role of perceived and actual motor competency on children’s physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness during middle childhood. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2017, 36, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, T.; Huhtiniemi, M.; Salin, K.; Seppälä, S.; Lahti, J.; Hakonen, H.; Stodden, D.F. Motor competence, perceived physical competence, physical fitness, and physical activity within Finnish children. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2019, 29, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaverdi, Z.; Bahram, A.; Stodden, D.; Kazemnejad, A. The relationship between actual motor competence and physical activity in children: Mediating roles of perceived motor competence and health-related physical fitness. J. Sports Sci. 2016, 34, 1523–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevans, K.; Fitzpatrick, L.-A.; Sanchez, B.; Forrest, C.B. Individual and Instructional Determinants of Student Engagement in Physical Education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2010, 29, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haerens, L.; Kirk, D.; Cardon, G.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Vansteenkiste, M. Motivational profiles for secondary school physical education and its relationship to the adoption of a physically active lifestyle among university students. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2010, 16, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, M.A.; Machida, M. The Role of Sport as a Social Status Determinant for Children. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2011, 82, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.L. Youth peer relationships in sport. In Social Psychology in Sport; Jowett, S., Lavallee, D., Eds.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2006; pp. 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich-French, S.; Smith, A. Perceptions of relationships with parents and peers in youth sport: Independent and combined prediction of motivational outcomes. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2006, 7, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Roberts, G.C. Physical competence and the development of children’s peer relations. Quest 1987, 39, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Blum, M.; Valkanover, S.; Conzelmann, A. Motor ability and self-esteem: The mediating role of physical self-concept and perceived social acceptance. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 17, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrmann, H.G.; Bratton, R.D. Athletic Participation and Status of Alberta High School Girls. Int. Rev. Sport Sociol. 1977, 12, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, E.; Leaper, C. A Longitudinal Investigation of Sport Participation, Peer Acceptance, and Self-esteem among Adolescent Girls and Boys. Sex Roles 2006, 55, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, S.A.; Swann, C.; Allen, M.S.; Schweickle, M.J.; Magee, C.A. Bidirectional Associations between Sport Involvement and Mental Health in Adolescence. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedard, C.; Hanna, S.; Cairney, J. A Longitudinal Study of Sport Participation and Perceived Social Competence in Youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 66, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shima, T.; Tai, K.; Nakao, H.; Shimofure, T.; Arai, Y.; Kiyama, K.; Onizawa, Y. Association between self-reported empathy and sport experience in young adults. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedag. 2021, 21, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodersen, N.H.; Steptoe, A.; Williamson, S.; Wardle, J. Sociodemographic, developmental, environmental, and psychological correlates of physical activity and sedentary behavior at age 11 to 12. Ann. Behav. Med. 2005, 29, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, A.C.; Nickerson, P.; Wright, K.L. Structured leisure activities in middle childhood: Links to well-being. J. Community Psychol. 2003, 31, 641–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.A.; Adler, P. Peer Power: Preadolescent Culture and Identity; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Serafica, F.C.; Blyth, D.A. Continuities and Changes in the Study of Friendship and Peer Groups during Early Adolescence. J. Early Adolesc. 1985, 5, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich-French, S.; Smith, A. Social and motivational predictors of continued youth sport participation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2009, 10, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.L. Peer relationships in physical activity contexts: A road less traveled in youth sport and exercise psychology research. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2003, 4, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R.M.; Young, J.A.; Harvey, J.T.; Charity, M.J.; Payne, W.R. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeijes, J.; Van Busschbach, J.T.; Wieringa, T.H.; Kone, J.; Bosscher, R.J.; Twisk, J.W.R. Sports participation and health-related quality of life in children: Results of a cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vella, S.A.; Cliff, D.P.; Magee, C.A.; Okely, A.D. Sports Participation and Parent-Reported Health-Related Quality of Life in Children: Longitudinal Associations. J. Pediatr. 2014, 164, 1469–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, K.H.; Bukowski, W.M.; Parker, J.G. Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Social, Emotional, and Personality Development; Eisenberg, N., Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 571–645. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford-Smith, M.E.; Brownell, C.A. Childhood peer relationships: Social acceptance, friendships, and peer networks. J. Sch. Psychol. 2003, 41, 235–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Y.; Han, L.H.; Zhang, J.H.; Luo, S.; Hu, J.W.; Sun, K. The influence of physical activity, sedentary behavior on health-related quality of life among the general population of children and adolescents: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreiskaemper, D.; Utesch, T.; Tietjens, M. The Perceived Motor Competence Questionnaire in Childhood (PMC-C). J. Mot. Learn. Dev. 2018, 6, S264–S280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, A.C.; Hartman, E.; Smits, I.; Hemker, B.T.; Spithoff, M.; Mombarg, R.; Kannekens, L.; Moolenaar, B. Peiling Bewegingsonderwijs 2016 Technische Rapportage; GION Onderwijs/Onderzoek: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, E.; Houwen, S.; Visscher, C. Motor Skill Performance and Sports Participation in Deaf Elementary School Children. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2011, 28, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelladurai, P.; Saleh, S.D. Preferred Leadership in Sports. Can. J. Appl. Sci. 1978, 3, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Landers, D.M.; Lüschen, G. Team performance outcome and the cohesiveness of competitive coaching groups. In Essential Readings in Sport and Exercise Psychology; Smith, D., Bar-Eli, M., Eds.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2007; pp. 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables; Version 4.2.; Muthén and Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Enders, C.K. Applied Missing Data Analysis; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannatta, K.; Gartstein, M.; Zeller, M.; Noll, R.B. Peer acceptance and social behavior during childhood and adolescence: How important are appearance, athleticism, and academic competence? Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2009, 33, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallhead, T.L.; Ntoumanis, N. Effects of a Sport Education Intervention on Students’ Motivational Responses in Physical Education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2004, 23, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, A.; Mumenthaler, F.; Nagel, S. Friendships in Integrative Settings: Network Analyses in Organized Sports and a Comparison with School. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opstoel, K.; Chapelle, L.; Prins, F.J.; De Meester, A.; Haerens, L.; Van Tartwijk, J.; De Martelaer, K. Personal and social development in physical education and sports: A review study. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 26, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opstoel, K.; Prins, F.; Jacobs, F.; Haerens, L.; van Tartwijk, J.; De Martelaer, K. Physical education teachers’ perceptions and operationalisations of personal and social development goals in primary education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2022, 28, 968–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.R. Teach the Children Well: A Holistic Approach to Developing Psychosocial and Behavioral Competencies Through Physical Education. Quest 2011, 63, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcellos, D.; Parker, P.D.; Hilland, T.; Cinelli, R.; Owen, K.B.; Kapsal, N.; Lee, J.; Antczak, D.; Ntoumanis, N.; Ryan, R.M.; et al. Self-determination theory applied to physical education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 112, 1444–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, F.M.; Mouratidis, A.; Pulido, J.J.; López-Gajardo, M.A.; Sánchez-Oliva, D. Perceived teachers’ behavior and students’ engagement in physical education: The mediating role of basic psychological needs and self-determined motivation. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2020, 27, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, C.; Fisher, L.; Berkey, C.; Colditz, G. Adolescent Physical Activity and Perceived Competence: Does Change in Activity Level Impact Self-Perception? J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 40, 462.e1–462.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruijn, A.; Mombarg, R.; Timmermans, A. The importance of satisfying children’s basic psychological needs in primary school physical education for PE-motivation, and its relations with fundamental motor and PE-related skills. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2021, 27, 422–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinides, P.; Montalvo, R.; Silverman, S. Teaching processes in elementary physical education classes taught by specialists and nonspecialists. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2013, 36, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, G.; Manross, M.; Hopple, C.; Sitzman, T. Novice and Experienced Children’s Physical Education Teachers: Insights into Their Situational Decision Making. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 1993, 12, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Individual Sports (n = 66) | Team Sports (n = 94) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Min.–Max. | Mean (SD) | Min.–Max. | Mean (SD) | Min.–Max. | |

| Perceived motor competence | 3.11 (0.45) | 1.96–4.00 | 2.99 (0.46) | 2.04–4.00 | 3.24 (0.42) | 1.96–4.00 |

| Sport frequency | 2.27 (1.29) | 0–7 | 1.83 (1.17) | 0–7 | 3.01 (0.79) | 1–5 |

| Social preference PE | 0.00 (1.55) | −4.18–3.13 | −0.05 (1.62) | −4.18–2.95 | 0.11 (1.52) | −3.54–3.13 |

| Social preference classroom | 0.00 (1.58) | −4.42–3.34 | 0.08 (1.73) | −4.42–3.34 | −0.01 (1.50) | −3.70–3.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Bruijn, A.G.M.; van der Wilt, F. Social Acceptance in Physical Education and the Regular Classroom: Perceived Motor Competency and Frequency and Type of Sports Participation. Children 2023, 10, 568. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030568

de Bruijn AGM, van der Wilt F. Social Acceptance in Physical Education and the Regular Classroom: Perceived Motor Competency and Frequency and Type of Sports Participation. Children. 2023; 10(3):568. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030568

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Bruijn, Anne G. M., and Femke van der Wilt. 2023. "Social Acceptance in Physical Education and the Regular Classroom: Perceived Motor Competency and Frequency and Type of Sports Participation" Children 10, no. 3: 568. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030568

APA Stylede Bruijn, A. G. M., & van der Wilt, F. (2023). Social Acceptance in Physical Education and the Regular Classroom: Perceived Motor Competency and Frequency and Type of Sports Participation. Children, 10(3), 568. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030568