Effects of Telerehabilitation-Based Structured Home Program on Activity, Participation and Goal Achievement in Preschool Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Triple-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

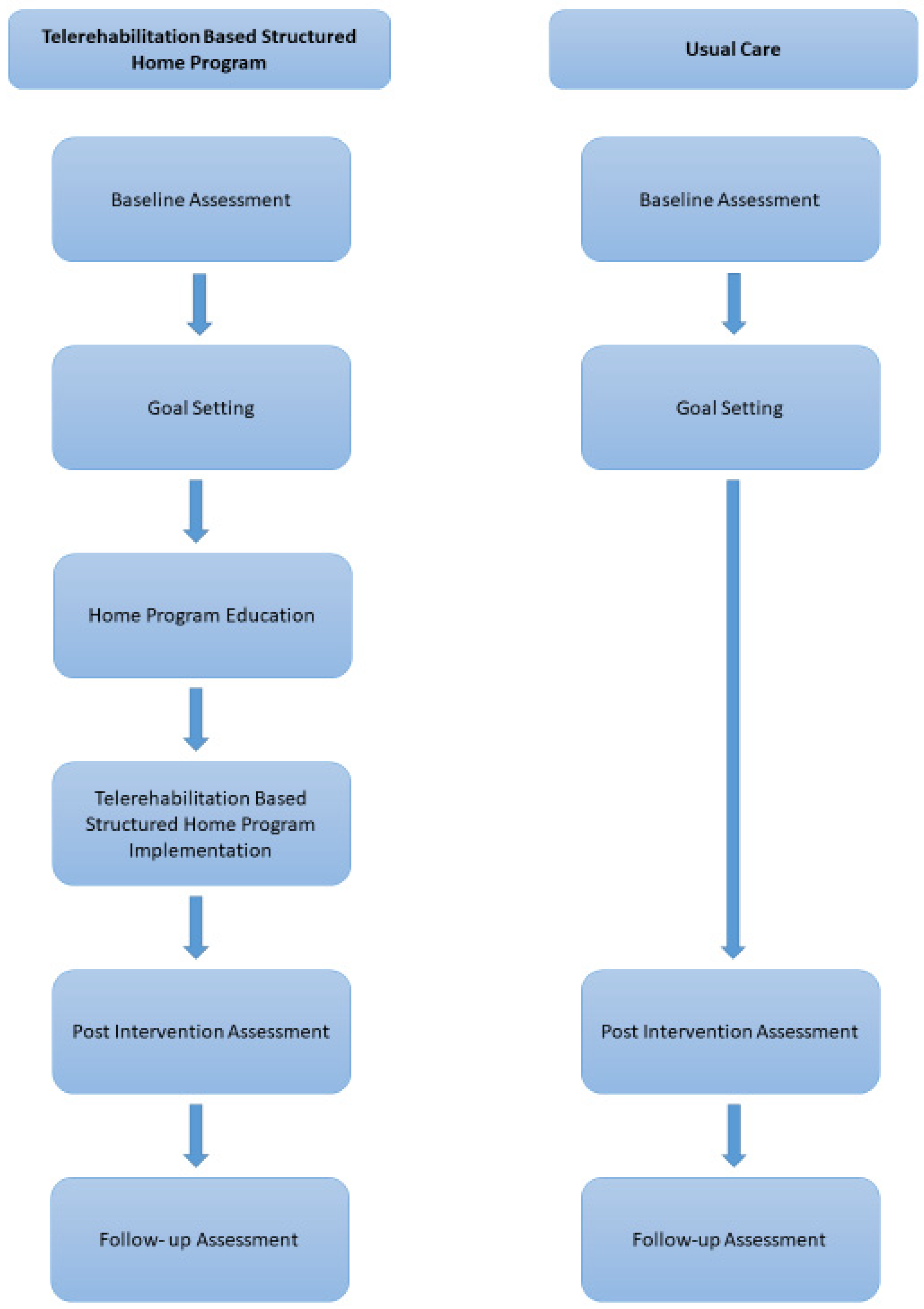

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Classification Tools

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.4.1. Gross Motor Function Measure-66 (GMFM-66)

2.4.2. Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI)

2.4.3. Goal Attainment Scale (GAS)

2.4.4. Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)

2.4.5. Interventions

2.5. Telerehabilitation-Based Structured Home Program

2.6. Usual Care

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Adverse Events

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth, N.; Leviton, A.; Goldstein, A.; Bax, M.; Dimano, D. A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007, 109, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF); World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Lau, E.Y.H.; Cheng, D.P.W. An exploration of the participation of kindergarten-aged hong kong children in extra curricular activities. J. Early Child. Res. 2016, 14, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan-Oliel, N.; Shikako-Thomas, K.; Majnemer, A. Quality of life and leisure participation in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities: A thematic analysis of the literature. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keawutan, P.; Bell, K.L.; Oftedal, S.; Davies, P.S.; Ware, R.S.; Boyd, R.N. Relationship between habitual physical activity, motor capacity, and capability in children with cerebral palsy aged 4–5 years across all functional abilities. Disabil. Health J. 2018, 11, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostam Zadeh, O.; Amini, M.; Hasani Mehraban, A. Comparison of Participation of Children with Cerebral Palsy Aged 4 to 6 in Occupa-tions with Normal Peers. J. Rehabil 2016, 17, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: Children & Youth Version: ICF-CY; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Di Marino, E.; Tremblay, S.; Khetani, M.; Anaby, D. The effect of child, family and environmental factors on the participation of young children with disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2018, 11, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reedman, S.; Boyd, R.N.; Sakzewski, L. The efficacy of interventions to increase physical activity participation of children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 9, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I.; Cusick, A.; Lowe, K. A pilot study on the impact of occupational therapy home programming for young children with cerebral palsy. Am. J. Occup Ther. 2007, 6, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I.; Berry, J. Home program intervention effectiveness evidence. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pedi 2014, 34, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I.; Mcintyre, S.; Morgan, C.; Campbell, L.; Dark, L.; Morton, N.; Goldsmith, S. A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: State of the evidence. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2013, 55, 885–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, L.W.; Geijen, M.M.; Kleijnen, J.; Rameckers, E.A.; Schnackers, M.L.; Smeets, R.J.; Janssen-Potten, Y.J. Feasibility and effectiveness of home-based therapy programmes for children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoros, D.; Russell, T.; Latifi, R. Telerehabilitation: Current perspectives. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2008, 131, 191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Camden, C.; Pratte, G.; Fallon, F.; Couture, M.; Berbari, J.; Tousignant, M. Diversity of practices in telerehabilitation for children with disabilities and effective intervention characteristics: Results from a systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 3424–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakzewski, L.; Reedman, S.; McLeod, K.; Thorley, M.; Burgess, A.; Trost, S.; Ahmadi, M.; Rowell, D.; Chatfield, M.; Bleyenheuft, Y.; et al. Preschool HABIT-ILE: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial to determine efficacy of intensive rehabilitation compared with usual care to improve motor skills of children, aged 2–5 years, with bilateral cerebral palsy. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e041542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palisano, R.; Rosenbaum, P.; Walter, S.; Russell, D.; Wood, E.; Galuppi, B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1997, 39, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, A.-C.; Krumlinde-Sundholm, L.; Rösblad, B.; Beckung, E.; Arner, M.; Öhrvall, A.-M.; Rosenbaum, P. The Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) for children with cerebral palsy: Scale development and evidence of validity and reliability. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2006, 48, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidecker, M.J.; Paneth, N.; Rosenbaum, P.L.; Kent, R.D.; Lillie, J.; Eulenberg, J.B.; Chester, J.R.K.; Johnson, B.; Michalsen, L.; Evatt, M. Developing and validating the Communication Function Classification System for individuals with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2011, 53, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günel, M.K. Motor Fonksiyon Ölçütü KMFÖ-66 ve KMFM-88 Kullanici Klavuzu, 2nd ed.; Hipokrat Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sritipsukho, P. Inter-rater and intra-rater reliability of the gross motor function measure (GMFM-66) by Thai pediatric physical therapists. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2011, 94, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Vos-Vromans, D.C.W.M.; Ketelaar, M.; Gorter, J.W. Responsiveness of evaluative measures for children with cerebral palsy: The Gross Motor Function Measure and the Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory. Disabil. Rehabil. 2005, 27, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenbeek, D.; Gorter, J.W.; Ketelaar, M.; Galama, K.; Lindeman, E. Responsiveness of Goal Attainment Scaling in comparison to two standardized measures in outcome evaluation of children with cerebral palsy. Clin. Rehabil. 2011, 25, 1128–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkerk, G.J.; Wolf MJ, M.; Louwers, A.M.; Meester-Delver, A.; Nollet, F. The reproducibility and validity of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure in parents of children with disabilities. Clin. Rehabil. 2006, 20, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, L.R.; Grinde, K.; McCormick, C. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: A Feasible Multidisciplinary Outcome Measure for Pediatric Telerehabilitation. Int. J. Telerehabilitation 2021, 13, e6372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, R.-G.; Yang, C.-N.; Qu, Y.-L.; Koduri, M.P.; Chien, C. WEffectiveness of hand-arm bimanual intensive training on upper extremity function in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neuro 2020, 25, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarello, L.A.; Palisano, R.J.; Orlin, M.N.; Chang, H.J.; Begnoche, D.; An, M. Understanding participation of preschool-age children with cerebral palsy. J. Early Interv. 2012, 34, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Dahab, S.M.; Alheresh, R.A.; Malkawi, S.H.; Saleh, M.; Wong, J. Participation patterns and determinants of participation of young children with cerebral palsy. Aust Occup. Ther. J. 2021, 68, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imms, C.; Granlund, M.; Wilson, P.H.; Steenbergen, B.; Rosenbaum, P.L.; Gordon, A.M. Participation, both a means and an end: A conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferre, C.L.; Brandão, M.; Surana, B.; Dew, A.P.; Moreau, N.G.; Gordon, A.M. Caregiver-directed home-based intensive bimanual training in young children with unilateral spastic cerebral palsy: A randomized trial. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I.; Cusick, A.; Lannin, N. Occupational therapy home programs for cerebral palsy: Double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 2009, 124, e606–e614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P. Family and quality of life: Key elements in intervention in children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2011, 53, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamm, E.L.; Rosenbaum, P. Family-centered theory: Origins, development, barriers, and supports to implementation in rehabilitation medicine. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehab. 2008, 89, 1618–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, P.; King, S.; Law, M.; King, G.; Evans, J. Family-centred service: A conceptual framework and research review. In Family-Centred Assessment and Intervention in Pediatric Rehabilitation, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- ØstensjØ, S.; Øien, I.; Fallang, B. Goal-oriented rehabilitation of preschoolers with cerebral palsy—A multi-case study of combined use of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) and the Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS). Dev. Neurorehabil. 2008, 11, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Attainment Level | Score | Activity-Based Example | Participation-Based Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Much less than expected outcome | −2 | Cannot use the assistive device with the support of another person. | Cannot ambulate in kindergarten with the support of another person with the assistive device. |

| Somewhat less than expected outcome | −1 | Can use the assistive device with the support of another person. | Can ambulate in kindergarten with the support of someone else with the assistive device. |

| Expected performance by the end of the measurement period | 0 | Can use the assistive device with close supervision of their parents. | Can ambulate in kindergarten independently with close supervision of their teacher. |

| Somewhat more than expected outcome | 1 | Can use the assistive device independently for 1 m. | Can walk in kindergarten 1 m independently with an assistive device. |

| Much more than expected outcome | 2 | Can use the assistive device independently for 5 m | Can move around the kindergarten with an assistive device. |

| UC + TR-SHP (n = 23) | UC (n = 20) | Z | p * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||||||

| Age (years) | 4.63 ± 1.06 | 4.70 ± 1.14 | −0.272 | 0.785 | |||

| n | % | n | % | χ2 | p | ||

| Gender | Girl | 11 | 47.8 | 12 | 40 | 0.637 | 0.425 |

| Boy | 12 | 52.2 | 8 | 60 | |||

| GMFCS | Level I | 6 | 26.1 | 3 | 15 | −0.801 | 0.423 |

| Level II | 2 | 8.7 | 2 | 10 | |||

| Level III | 4 | 17.4 | 6 | 30 | |||

| Level IV | 6 | 26.1 | 1 | 5 | |||

| Level V | 5 | 21.7 | 8 | 40 | |||

| MACS | Level I | 6 | 26.1 | 6 | 30 | −0.188 | 0.851 |

| Level II | 1 | 4.3 | 3 | 15 | |||

| Level III | 6 | 26.1 | 3 | 15 | |||

| Level IV | 4 | 17.4 | 1 | 5 | |||

| Level V | 6 | 26.1 | 7 | 35 | |||

| CFCS | Level I | 13 | 56.5 | 9 | 45 | −1.125 | 0.261 |

| Level II | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Level III | 3 | 13 | 1 | 5 | |||

| Level IV | 3 | 13 | 3 | 15 | |||

| Level V | 4 | 17.4 | 7 | 35 | |||

| UC + TR-SHP (n = 23) | UC (n = 20) | T | p * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| GAS | 36.36 ± 0.04 | 36.34 ± 0.05 | 1.642 | 0.100 |

| GMFM | 49.15 ± 38.53 | 42.07 ± 37.25 | 0.793 | 0.610 |

| COPM-P | 8.60 ± 0.84 | 5.45 ± 2.28 | 1.845 | 0.055 |

| COPM-S | 8.60 ± 4.05 | 5.55 ± 0.54 | 1.970 | 0.221 |

| PEDI-SC | 27.82 ± 25.45 | 22.45 ± 22.20 | 0.733 | 0.154 |

| PEDI-MOB | 23.73 ± 24.46 | 14.35 ± 19.88 | 1.367 | 0.031 |

| PEDI-SF | 24.73 ± 24.98 | 25.30 ± 26.41 | −0.071 | 0.306 |

| UC + TR-SHP (n = 23) | UC (n = 20) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | p * | Pairwise Comparison | T1 | T2 | T3 | p * | Pairwise Comparison | |

| X ± SD | X ± SD | X ± SD | X ± SD | X ± SD | X ± SD | |||||

| GMFM | 49.15 ± 38.53 | 53.15 ± 3.25 | 53.20 ± 38.17 | 0.001 * | T1–T2 T1–T3 | 42.07 ± 37.25 | 42.34 ± 37.14 | 42.60 ± 37.29 | 0.053 | - |

| PEDI-SC | 27.82 ± 25.45 | 30.69 ± 25.50 | 30.73 ± 25.58 | 0.000 * | T1–T2 T1–T3 | 22.45 ± 22.20 | 22.50 ± 22.28 | 22.50 ± 22.28 | 0.330 | - |

| PEDI-MOB | 23.73 ± 24.46 | 25.60 ± 24.36 | 25.65 ± 24.33 | 0.000 * | T1–T2 T1–T3 | 14.35 ± 19.88 | 14.45 ± 19.81 | 14.55 ± 19.89 | 0.174 | - |

| PEDI-SF | 24.73 ± 24.98 | 24.95 ± 24.96 | 24.95 ± 24.96 | 0.135 | - | 25.30 ± 26.41 | 25.30 ± 26.41 | 25.30 ± 26.41 | 1.00 | - |

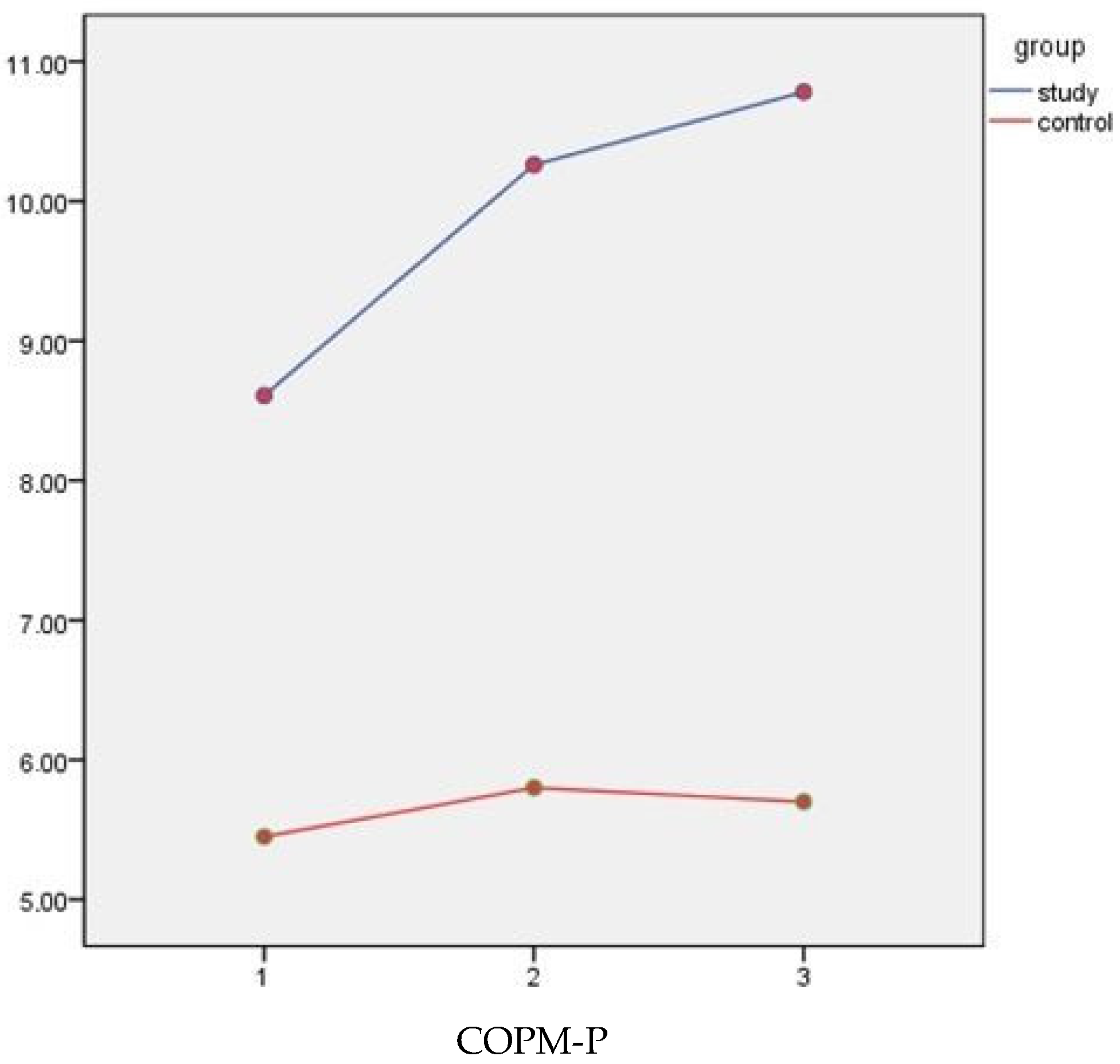

| COPM-P | 8.60 ± 0.84 | 10.26 ± 0.91 | 10.78 ± 0.99 | 0.005 * | T1–T3 | 5.45 ± 2.28 | 5.80 ± 2.48 | 5.70 ± 3.22 | 0.609 | - |

| COPM-S | 8.60 ± 4.05 | 10.26 ± 4.39 | 10.78 ± 4.76 | 0.005 * | T1–T3 | 5.55 ± 0.54 | 5.15 ± 0.55 | 5.45 ± 0.72 | 0.232 | - |

| GAS | 36.36 ± 0.04 | 62.28 ± 8.52 | 60.14 ± 8.82 | 0.000 * | T1–T2 T1–T3 | 36.34 ± 0.05 | 37.94 ± 3.96 | 37.26 ± 2.78 | 0.24 | - |

| T | UC + TR-SHP (n = 23) | Effect Size (d) | UC (20) | Effect Size (d) | p * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1–T2 | T1–T3 | T1–T2 | T1–T3 | |||||

| X ± SD | X ± SD | F/p | ||||||

| GMFM | T1 | 49.15 ± 38.53 | 1.04 | 1.05 | 42.07 ± 37.25 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 14.86/0.000 * |

| T2 | 53.15 ± 38.25 | 42.34 ± 37.14 | ||||||

| T3 | 53.20 ± 38.17 | 42.60 ± 37.29 | ||||||

| PEDI-SC | T1 | 27.82 ± 25.45 | 1.12 | 1.14 | 22.45 ± 22.20 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 23.05/0.000 * |

| T2 | 30.69 ± 25.50 | 22.50 ± 22.28 | ||||||

| T3 | 30.73 ± 25.58 | 22.50 ± 22.28 | ||||||

| PEDI-MOB | T1 | 23.73 ± 24.46 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 14.35 ± 19.88 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 18.90/0.000 * |

| T2 | 25.60 ± 24.36 | 14.45 ± 19.81 | ||||||

| T3 | 25.65 ± 24.33 | 14.55 ± 19.89 | ||||||

| PEDI-SF | T1 | 24.73 ± 24.98 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 25.30 ± 26.41 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.74/0.194 |

| T2 | 24.95 ± 24.96 | 25.30 ± 26.41 | ||||||

| T3 | 24.95 ± 24.96 | 25.30 ± 26.41 | ||||||

| COPM-P-T | T1 | 8.60 ± 0.84 | 3.64 | 4.72 | 5.45 ± 2.28 | 1.46 | 0.80 | 3.34/0.040 * |

| T2 | 10.26 ± 0.91 | 5.80 ± 2.48 | ||||||

| T3 | 10.78 ± 0.99 | 5.70 ± 3.22 | ||||||

| COPM-M-T | T1 | 8.60 ± 4.05 | 0.75 | 2.87 | 5.55 ± 2.41 | 0.16 | 0.35 | 6.68/0.006 * |

| T2 | 10.26 ± 4.39 | 5.15 ± 2.47 | ||||||

| T3 | 10.78 ± 4.76 | 5.45 ± 3.21 | ||||||

| GAS | T1 | 36.36 ± 0.04 | 4.30 | 4.64 | 36.34 ± 0.05 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 134.57/0.000 * |

| T2 | 62.28 ± 8.52 | 37.94 ± 3.96 | ||||||

| T3 | 60.14 ± 8.82 | 37.94 ± 2.78 | ||||||

| UC + TR-SHP (n = 23) | UC (n = 20) | Z | p * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| HP dose (hour) | 55.95 ± 0.20 | 27.70 ± 15.53 | −5530 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sel, S.A.; Günel, M.K.; Erdem, S.; Tunçdemir, M. Effects of Telerehabilitation-Based Structured Home Program on Activity, Participation and Goal Achievement in Preschool Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Triple-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. Children 2023, 10, 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030424

Sel SA, Günel MK, Erdem S, Tunçdemir M. Effects of Telerehabilitation-Based Structured Home Program on Activity, Participation and Goal Achievement in Preschool Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Triple-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. Children. 2023; 10(3):424. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030424

Chicago/Turabian StyleSel, Sinem Asena, Mintaze Kerem Günel, Sabri Erdem, and Merve Tunçdemir. 2023. "Effects of Telerehabilitation-Based Structured Home Program on Activity, Participation and Goal Achievement in Preschool Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Triple-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial" Children 10, no. 3: 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030424

APA StyleSel, S. A., Günel, M. K., Erdem, S., & Tunçdemir, M. (2023). Effects of Telerehabilitation-Based Structured Home Program on Activity, Participation and Goal Achievement in Preschool Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Triple-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. Children, 10(3), 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030424