Socio-Emotional Competencies Required by School Counsellors to Manage Disruptive Behaviours in Secondary Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Mental-Health Problems in Children and Adolescents

1.2. School Conflict: The Current Situation

Competences of Educational Guidance Counsellors for Conflicts: Challenges and Perspectives

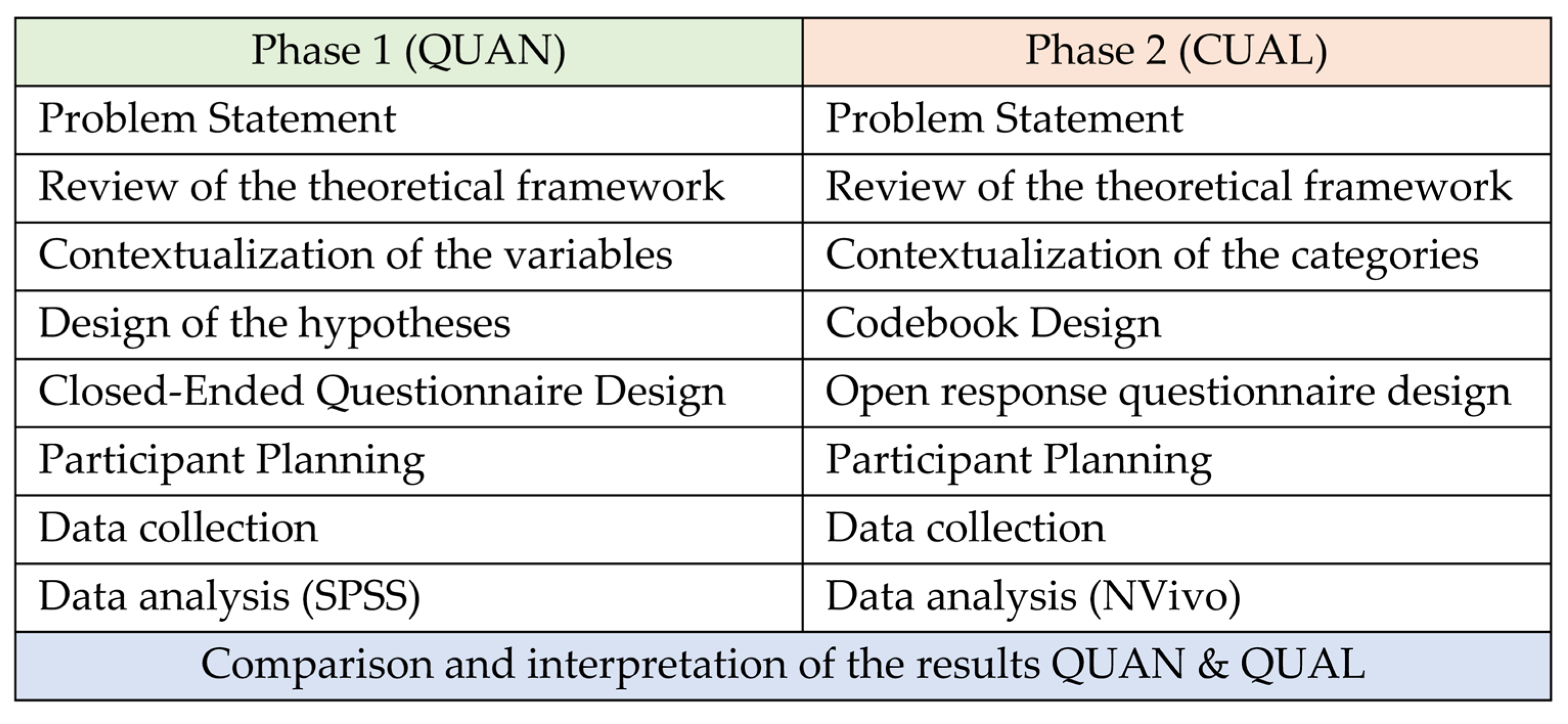

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive QUAN Data Analysis

3.2. Inferential QUAN Data Analysis

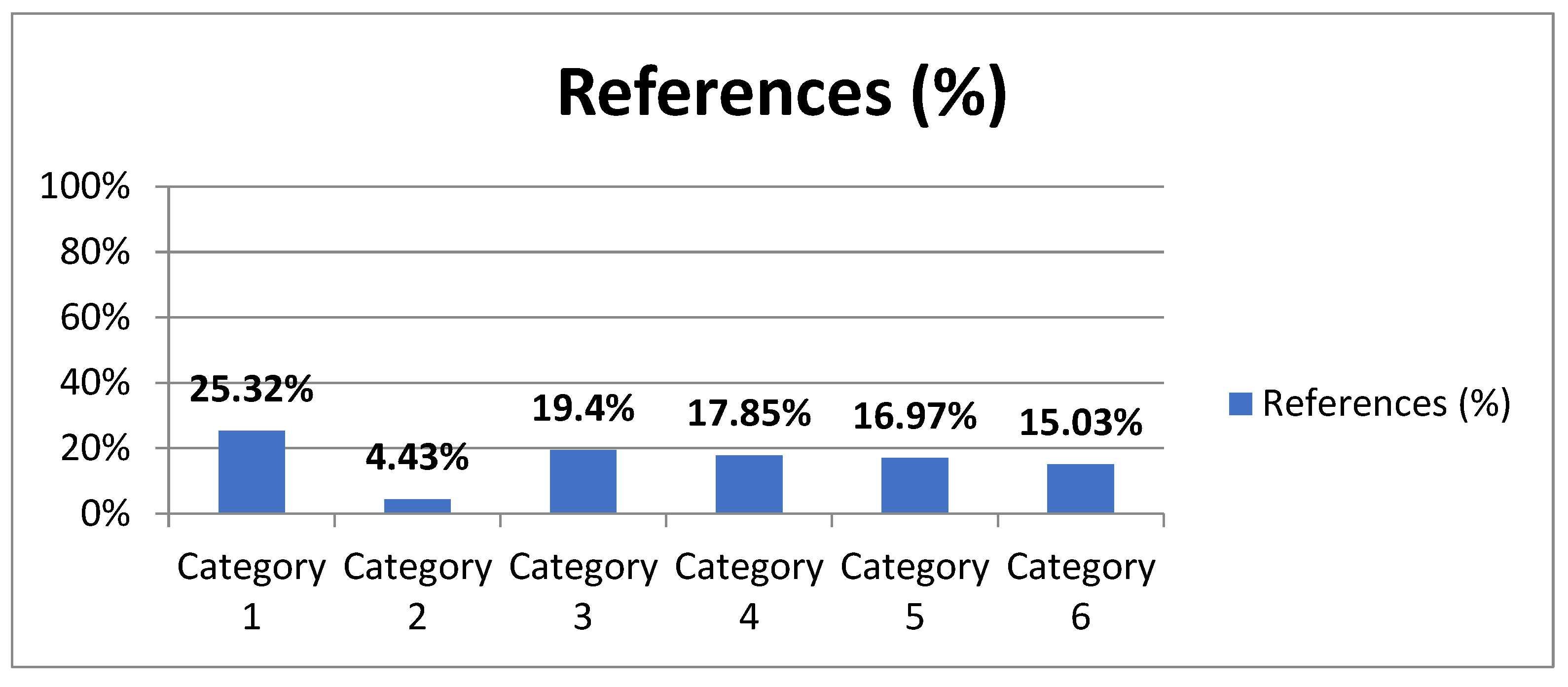

3.3. Qualitative Content Analysis

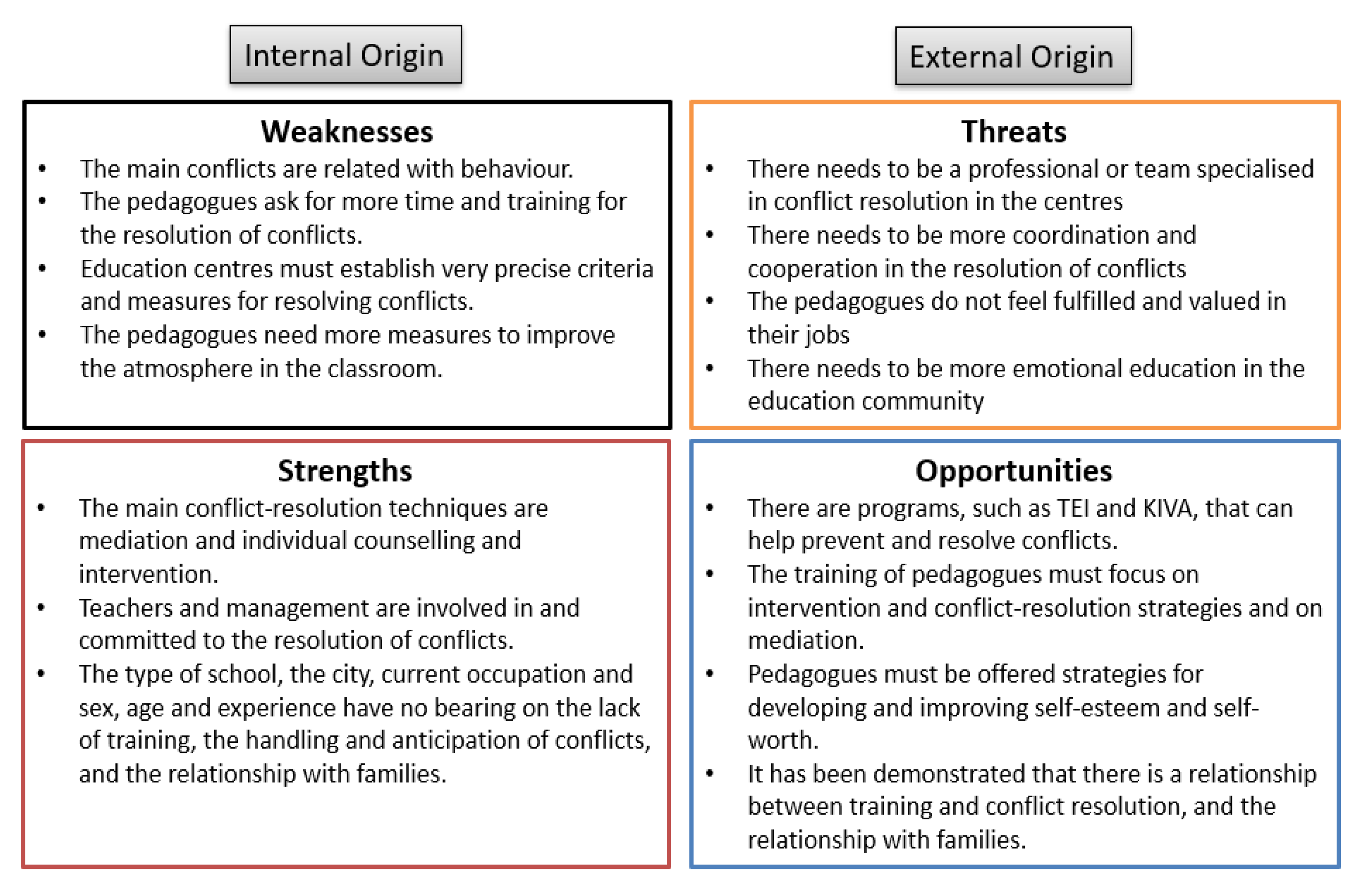

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Normality (Kolmogorov–Smirnov) | Randomness (Rachas) | Homoscedasticity (Levene) | Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I consider that I need training to manage conflicts in the classroom or at the centre | 0.000 | 0.784 | Non-parametric | |

| The management of conflicts in the centre is part of my duties as a counsellor | 0.000 | 0.980 | Non-parametric | |

| In my profession it is difficult to anticipate conflicts and prevent them | 0.000 | 0.068 | Non-parametric | |

| The relationship with the families of the students is a difficult area to manage | 0.000 | 0.690 | Non-parametric |

References

- Ballverka, N.; Gómez-Benito, J.; Hidalgo, M.D.; Gorostiaga, A.; Espada, J.P.; Padilla, J.L.; Santed, M.A. Las consecuencias psicológicas de la COVID-19 y el confinamiento. In Informe de Investigación; Universidad del País Vasco: Leioa, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hon, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on collage students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. Nurturing the Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Children and Young People during Crises; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radez, J.; Reardon, T.; Creswell, C.; Lawrence, P.J.; Evdoka-Burton, G.; Waite, P. Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano-Sarmiento, Á.; Sanz, R. Reflexiones y propuestas prácticas para desarrollar la capacidad de resiliencia frente a los conflictos en la escuela. Publ. Fac. De Educ. Y Humanid. Del Campus De Melilla 2019, 49, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosma, A.; Balazsi, R.; Băban, A. Bullying victimization and internalizing problems in school aged children: A longitudinal approach. Cogn. Brain Behav. 2018, 22, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, C.; Hertz-Palmor, N.; Yadan-Barzilai, Y.; Saker, T.; Kritchmann-Lupo, M.; Bloch, Y. Increase in Referrals of Children and Adolescents to the Psychiatric Emergency Room Is Evident Only in the Second Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic—Evaluating 9156 Visits from 2010 through 2021 in a Single Psychiatric Emergency Room. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Fernández, G.; Rodríguez-Valverde, M.; Reyes-Martín, S.; Hernández-Lopez, M. The Role of Psychological Inflexibility and Experiential Approach on Mental Health in Children and Adolescents: An Exploratory Study. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meherali, S.; Punjani, N.; Louie-Poon, S.; Abdul Rahim, K.; Das, J.K.; Salam, R.A.; Lassi, Z.S. Mental health of children and adolescents amidst COVID-19 and past pandemics: A rapid systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.Y.; Wang, L.N.; Liu, J.; Fang, S.F.; Jiao, F.Y.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M.; Somekh, E. Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. J. Pediatr. 2020, 221, 264–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Smith, L.E.; Webster, R.K.; Weston, D.; Woodland, L.; Hall, I.; Rubin, G.J. The impact of unplanned school closure on children’s social contact: Rapid evidence review. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 2000188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, R.; Pagerols, M.; Prat, R.; Español-Martín, G.; Rivas, C.; Dolz, M.; Haro, J.M.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A.; Ribasés, M.; Casas, M. Changes in the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Lockdown: Associated Factors and Life Conditions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, B. The State of the World’s Children 2021: On My Mind—Promoting, Protecting and Caring for Children’s Mental Health; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Samji, H.; Wu, J.; Ladak, A.; Vossen, C.; Stewart, E.; Dove, N.; Long, D.; Snell, G. Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth–a systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fazio, N.; Morena, D.; Delogu, G.; Volonnino, G.; Manetti, F.; Padovano, M.; Scopetti, M.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. Mental Health Consequences of COVID-19 Pandemic Period in the European Population: An Institutional Challenge. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elharake, J.A.; Akbar, F.; Malik, A.A.; Gilliam, W.; Omer, S.B. Mental health impact of COVID-19 among children and college students: A systematic review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez Ochoa, R.A.; Vázquez, P.; Velazco Luna, I.; Amezcua, A.; Aguirre Quezada, J.P.; Vargas, T.; Díaz Pérez, X.N.; Guzmán Domínguez, C.; Velasco Rodríguez, S.P.; Pérez Pérez, C.O.; et al. El impacto de la pandemia de COVID-19 en la deserción escolar y salud mental de niñas, niños, adolescentes y jóvenes mayas de Chiapas. In Propuestas Para su Abordaje; Instituto Belisario Domínguez: Centro, Mexico, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Kaman, A.; Erhart, M.; Devine, J.; Schlack, R.; Otto, C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 31, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgilés, M.; Francisco, R.; Delvecchio, E.; Espada, J.P.; Mazzeschi, C.; Pedro, M.; Morales, A. Psychological Symptoms in Italian, Spanish and Portuguese Youth During the COVID-19 Health Crisis: A Longitudinal Study. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2022, 53, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.H.; Beames, J.R.; Newby, J.M.; Maston, K.; Christensen, H.; Werner-Seidler, A. The impact of COVID-19 on the lives and mental health of Australian adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 1465–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Kaman, A.; Erhart, M.; Piccoliori, G.; Plagg, B.; Mahlknecht, A.; Ausserhofer, D.; Engl, A.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Quality of Life and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents after the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Large Population-Based Survey in South Tyrol, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, Y.; Tiiri, E.; Khanal, P.; Khakurel, J.; Mishina, K.; Sourander, A. Feeling Unsafe at School and Associated Mental Health Difficulties among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Children 2021, 8, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Sarmiento, Á. Reflexiones en torno a la respuesta educativa frente a la violencia escolar. Edetania 2015, 2015, 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- González, A. TALIS 2018. Estudio Internacional de la Enseñanza y el Aprendizaje. Informe Español. Volumen II; Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Domenech, B.; Escortell-Sánchez, R. Sex and Grade Differences in Cyberbullying of Spanish Students of 5th and 6th Grade of Primary Education. An. De Psicol. 2018, 34, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J.W. Connecting adolescent suicide to the severity of bullying and cyberbullying. J. Sch. Violence 2019, 18, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertürk, R. Conflict in Schools: A Qualitative Study. Particip. Educ. Res. 2022, 9, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chocarro, E.; Garaigordobil, M. Bullying y cyberbullying: Diferencias de sexo en víctimas, agresores y observadores. Pensam. Psicológico 2019, 17, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldrum, R.C.; Patchin, J.W.; Young, J.T.; Hinduja, S. Bullying Victimization, Negative Emotions, and Digital Self-Harm: Testing a Theoretical Model of Indirect Effects. Deviant Behav. 2022, 43, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivnick, B.A.; Hassinger, J.A. The child in the school, the school in the community, and the community in the child: Linking psychic and social domains in school violence prevention. Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Stud. 2021, 18, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koran, S.; Koran, E. Classroom management and school science labs: A review of literature on classroom management strategies. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Stud. 2018, 5, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, D.K.; Mynatt, B.S.; Woodside, M. Novice school counselors’ experience in classroom management. J. Couns. Prep. Superv. 2017, 9, 33–62. Available online: https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol9/iss1/2/ (accessed on 10 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Vélaz de Medrano, C.; Manzanares, A.; López E y Manzano, N. Competencias y formación de los orientadores escolares: Estudio empírico en nueve comunidades autónomas. Rev. De Educ. 2013, Número Extraordinario, 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza, R.S.; Forero, E.A.S. El orientador de secundaria ante los conflictos y la violencia escolar. Ra Ximhai Rev. Científica De Soc. Cult. Y Desarro. Sosten. 2016, 12, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Geesa, R.L.; Elam, N.P.; Mayes, R.D.; McConnell, K.R.; McDonald, K.M. School leaders’ perceptions on comprehensive school counseling (CSC) evaluation processes: Adherence and implementation of the American School Counselor Association (ASCA) National Model. J. Educ. Leadersh. Policy Pract. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejudo, J. Competencias profesionales y competencias emocionales en orientadores escolares. Profr. Rev. De Currículum Y Form. De Profr. 2017, 21, 349–370. [Google Scholar]

- Cabanillas-García, J.L. Evolución de la Actitud, las Emociones y el Aprendizaje, en el Máster Universitario de Investigación en Formación del Profesorado y TIC en modalidad a distancia. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Extremadura, Badajoz, Spanje, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández, C.; Baptista, P. Metodología de la Investigación; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cabanillas-García, J.L.; Luengo-González, R.; Carvalho, J.L. Analysis of the Use, Knowledge and Problems of E-learning in a Distance Learning Master’s Programme. In Computer Supported Qualitative Research. WCQR 2022. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Costa, A.P., Moreira, A., Sánchez Gómez, M.C., Wa-Mbaleka, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 466, pp. 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cabanillas-García, J.L.; Martín-Sevillano, R.; Sánchez-Gómez, M.C.; Martín-Cilleros, M.V.; Verdugo-Castro, S.; Mena, J.; Pinto-Llorente, A.M.; Izquierdo-Álvarez, V.A.M.; Izquierdo-Álvarez, V. A Qualitative Study and Analysis on the Use, Utility, and Emotions of Technology by the Elderly in Spain. In Computer Supported Qualitative Research. WCQR 2022. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Costa, A.P., Moreira, A., Sánchez Gómez, M.C., Wa-Mbaleka, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 466, pp. 248–263. [Google Scholar]

- Werling, A.M.; Walitza, S.; Eliez, S.; Drechsler, R. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health care of children and adolescents in Switzerland: Results of a survey among mental health care professionals after one year of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellido, A.G. Programa TEI “tutoría entre iguales”. Innovación Educ. 2015, 25, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garandeau, C.F.; Laninga-Wijnen, L.; Salmivalli, C. Effects of the KiVa anti-bullying program on affective and cognitive empathy in children and adolescents. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2022, 51, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean ± SD/Frequency (Percentage) |

|---|---|

| Type of centre | |

| Public | 46 (30.9%) |

| Concerted | 92 (61.7%) |

| Private | 11 (7.4%) |

| Experience | 10.82 ± 7.69 |

| City | |

| Castellón | 12 (8.1%) |

| Valencia | 58 (39.9%) |

| Alcoy | 2 (1.3%) |

| Granada | 7 (4.7%) |

| Zaragoza | 3 (2%) |

| Málaga | 4 (2.7%) |

| Sevilla | 5 (3.4%) |

| Alicante | 25 (16.8%) |

| Madrid | 9 (6%) |

| Cádiz | 3 (2%) |

| Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | 3 (2%) |

| Cuenca | 4 (2.7%) |

| Palencia | 2 (1.3%) |

| Melilla | 1 (0.7%) |

| Teruel | 1 (0.7%) |

| Córdoba | 1 (0.7%) |

| Murcia | 4 (2.7%) |

| Mallorca | 1 (0.7%) |

| Toledo | 2 (1.3%) |

| Ceuta | 1 (0.7%) |

| Melilla | 1 (0.7%) |

| Current occupation | |

| School counsellor | 131 (87.9%) |

| External | 18 (12.1%) |

| Age | 38.65 ± 9.27 |

| Sex | |

| Men | 22 (14.8%) |

| Woman | 127 (85.2%) |

| Variable | Strongly Disagree | In Disagreement | Indifferent | In Agreement | Totally Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I consider that I need training to manage conflicts in the classroom or at the centre | 6 (4%) | 22 (28.9%) | 43 (14.8%) | 50 (33.6%) | 28 (18.8%) |

| The management of conflicts in the centre is part of my duties as a counsellor | 10 (6.7%) | 14 (9.4%) | 30 (20.1%) | 52 (34.9%) | 43 (28.9%) |

| In my profession it is difficult to anticipate conflicts and prevent them | 8 (5.4%) | 52 (34.9%) | 64 (43%) | 19 (12.8%) | 6 (4%) |

| The relationship with the families of the students is a difficult area to manage | 11 (7.4%) | 33 (22.1%) | 45 (30.2%) | 52 (34.9%) | 8 (5.4%) |

| Variable | Type of Centre (H de Kruskal–Wallis) | City (H de Kruskal–Wallis) | Current Occupation (U de Mann–Whitney) | Sex (U de Mann–Whitney) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | p = 0.841 | p = 0.707 | p = 0.384 | p = 0.357 |

| Item 2 | p = 0.337 | p = 0.365 | p = 0.619 | p = 0.247 |

| Item 3 | p = 0.102 | p = 0.493 | p = 0.983 | p = 0.470 |

| Item 4 | p = 0.317 | p = 0.890 | p = 0.673 | p = 0.079 |

| Variable | Experience (Pearson’s Correlation) | Age (Pearson’s Correlation) |

|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | CC = −0.142 | CC = −0.056 |

| p = 0.085 | p = 0.500 | |

| Item 2 | CC = 0.108 | CC = 0.062 |

| p = 0.191 | p = 0.454 | |

| Item 3 | CC = 0.011 | CC = 0.089 |

| p = 0.897 | p = 0.279 | |

| Item 4 | CC = −0.020 | CC = −0.043 |

| p = 0.813 | p = 0.601 |

| Variable | Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | X | CC = 0.062 | CC = 0.314 | CC = 0.273 |

| p = 0.449 | p = 0.000 ** | p = 0.001 ** | ||

| Item 2 | CC = 0.062 | X | CC = −0.038 | CC = 0.129 |

| p = 0.449 | p = 0.646 | p = 0.119 | ||

| Item 3 | CC = 0.314 | CC = −0.038 | X | CC = 0.122 |

| p = 0.000 ** | p = 0.646 | p = 0.139 | ||

| Item 4 | CC = 0.273 | CC = 0.129 | CC = 0.122 | X |

| p = 0.001 ** | p = 0.119 | p = 0.139 |

| Subcategory | References (n) |

|---|---|

| Mediation | 40 |

| Individual counselling and intervention | 31 |

| Dialogue and assertive communication | 25 |

| Counselling and intervention with families | 22 |

| Group counselling and intervention | 22 |

| Following norms and protocols | 19 |

| Behaviour modification | 14 |

| Social skills and emotional intelligence programme | 10 |

| Punishment or penalty | 10 |

| Coordination and guidance with teachers | 10 |

| Counselling and intervention at the level of the centre | 6 |

| Coordination with other areas | 5 |

| Knowing and analysing the conflict | 5 |

| Tutoring | 4 |

| Group dynamics | 4 |

| Follow-up | 4 |

| Prevention | 4 |

| Reprimand | 3 |

| Positive reinforcements | 3 |

| Reflection | 3 |

| Justice | 2 |

| Commitment form | 2 |

| Reflection sheets | 2 |

| Sociograms | 2 |

| Strategies for self-control | 2 |

| Authority | 1 |

| Motivation | 1 |

| Observation | 1 |

| Looking for solutions | 1 |

| Considers it is not included in their duties | 1 |

| Referring to the guidance department | 1 |

| Looking for an agreement between the affected parties | 1 |

| Subcategory | References (n) |

|---|---|

| Behaviour problems | 11 |

| Conduct disorders | 11 |

| Disruption | 10 |

| Indiscipline | 9 |

| Other related to the centres | 9 |

| Bullying | 3 |

| Violence between students | 2 |

| Cyberbullying | 1 |

| Subcategory | References (n) |

|---|---|

| Intervention and conflict-resolution strategies for teachers | 34 |

| Mediation | 29 |

| Strategies against inappropriate behaviour among students | 18 |

| Prevention programs | 16 |

| Managing relations with families | 15 |

| Emotional education | 14 |

| Improving relations and atmosphere in the classroom | 10 |

| New tendencies and perspectives | 9 |

| Cyberbullying | 8 |

| Techniques and strategies for students with disabilities | 6 |

| Bullying | 4 |

| Improving self-control | 4 |

| Techniques for maintaining discipline | 4 |

| Social skills | 4 |

| New technologies | 3 |

| Presenting real cases | 2 |

| None | 2 |

| Educational coaching | 2 |

| Motivation strategies | 2 |

| Addiction | 2 |

| Strategies for permanent, not temporary solutions | 2 |

| Techniques that do not use punishments or prizes | 2 |

| On cultural management | 1 |

| Improving self-esteem | 1 |

| Sex education | 1 |

| Legislation | 1 |

| Practical intervention in students | 1 |

| Stress management | 1 |

| Brief and systematic therapy | 1 |

| Individualised attention for students | 1 |

| Subcategory | References (n) |

|---|---|

| Figure of a professional or team specialised in harmonious school relations | 24 |

| Time | 20 |

| Involvement of the educational team | 19 |

| Training | 18 |

| Support from families | 15 |

| Cooperation and coordination with teachers | 14 |

| More guidance counsellors | 11 |

| Teachers or support personnel | 11 |

| More resources | 10 |

| Real measures and not so much bureaucracy | 6 |

| Following the intervention protocol | 5 |

| More pedagogues | 4 |

| More social educators | 4 |

| More interventions by social services | 4 |

| Coexistence classrooms | 4 |

| Swift response | 3 |

| More prevention plans and strategies | 3 |

| Information | 2 |

| More psychologists | 2 |

| Awareness-raising campaigns | 2 |

| Figure of a mediator (teacher or student) | 1 |

| Guidance team working more closely together | 1 |

| Social integrator | 1 |

| Subcategory | References (n) |

|---|---|

| More recognition, respect, and appreciation of one’s work | 44 |

| More time | 16 |

| Lack of training | 15 |

| More support in the workplace | 15 |

| More collaboration and cooperation between colleagues | 15 |

| Being able to better perform my professional functions | 6 |

| Feeling less pressure in my work | 6 |

| Permanent full-time contract instead of an internship | 4 |

| Better salaries | 4 |

| We need more resources | 4 |

| More commitment from colleagues | 3 |

| More collaboration on the part of families | 3 |

| Working on emotional education | 2 |

| Hiring more professionals for the guidance team | 2 |

| Being able to see the result of my work in students | 2 |

| Less intrusion in the workplace | 2 |

| Continuing to improve as a teacher | 1 |

| Acquiring more experience | 1 |

| More work and contact with the classrooms | 1 |

| New challenges | 1 |

| Subcategory | References (n) |

|---|---|

| I do feel both collectives are committed | 51 |

| I do not feel both collectives are committed | 38 |

| Sometimes I feel both collectives are committed | 33 |

| It depends on the person | 9 |

| I feel management is committed but teachers are not | 8 |

| Both collectives need to be more involved | 7 |

| It depends on the centre | 3 |

| There is only involvement in serious situations | 3 |

| Only at the beginning of the school year | 1 |

| It depends on age | 1 |

| It depends on training | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serrano, Á.; Sanz, R.; Cabanillas, J.L.; López-Lujan, E. Socio-Emotional Competencies Required by School Counsellors to Manage Disruptive Behaviours in Secondary Schools. Children 2023, 10, 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10020231

Serrano Á, Sanz R, Cabanillas JL, López-Lujan E. Socio-Emotional Competencies Required by School Counsellors to Manage Disruptive Behaviours in Secondary Schools. Children. 2023; 10(2):231. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10020231

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerrano, Ángela, Roberto Sanz, Juan Luis Cabanillas, and Elena López-Lujan. 2023. "Socio-Emotional Competencies Required by School Counsellors to Manage Disruptive Behaviours in Secondary Schools" Children 10, no. 2: 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10020231

APA StyleSerrano, Á., Sanz, R., Cabanillas, J. L., & López-Lujan, E. (2023). Socio-Emotional Competencies Required by School Counsellors to Manage Disruptive Behaviours in Secondary Schools. Children, 10(2), 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10020231