Insulin Resistance/Hyperinsulinemia Should Be Considered in the Prevention and Treatment of Essential Hypertension

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Point

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization The Top Ten Causes of Death. World Health Organization. Hypertension. 25 September 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Kjeldsen, S.E. Hypertension and cardiovascular risk: General aspects. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 129, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messerli, F.H.; Williams, B.; Ritz, E. Essential hypertension. Lancet 2007, 370, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimoldi, S.F.; Scherrer, U.; Messerli, F.H. Secondary arterial hypertension: When, who, and how to screen? Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, M. Historical perspectives on the management of hypertension. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2006, 8 (Suppl. S2), 15–20, quiz 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Iqbal, A.M.; Jamal, S.F. Essential Hypertension. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rossi, G.P.; Bagordo, D.; Rossi, F.B.; Pintus, G.; Rossitto, G.; Seccia, T.M. ‘Essential’ arterial hypertension: Time for a paradigm change. J. Hypertens. 2024, 42, 1298–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lebovitz, H.E. Insulin resistance: Definition and consequences. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2001, 109 (Suppl. S2), S135–S148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, A.M.; Acevedo, L.A.; Pennings, N. Insulin Resistance. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seravalle, G.; Grassi, G. Obesity and hypertension. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 122, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litwin, M.; Kułaga, Z. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and primary hypertension. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2021, 36, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gluvic, Z.; Zaric, B.; Resanovic, I.; Obradovic, M.; Mitrovic, A.; Radak, D.; Isenovic, E.R. Link between Metabolic Syndrome and Insulin Resistance. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2017, 15, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, B.; Sultana, R.; Greene, M.W. Adipose tissue and insulin resistance in obese. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 111315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearney, P.M.; Whelton, M.; Reynolds, K.; Muntner, P.; Whelton, P.K.; He, J. Global burden of hypertension: Analysis of worldwide data. Lancet 2005, 365, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrannini, E.; Buzzigoli, G.; Bonadonna, R.; Giorico, M.A.; Oleggini, M.; Graziadei, L.; Pedrinelli, R.; Brandi, L.; Bevilacqua, S. Insulin resistance in essential hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 317, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Aa, M.P.; Fazeli Farsani, S.; Knibbe, C.A.; de Boer, A.; van der Vorst, M.M. Population-Based Studies on the Epidemiology of Insulin Resistance in Children. J. Diabetes Res. 2015, 2015, 362375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rao, K.; Yang, J.; Wu, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, X.; Dong, Y. Association Between the Metabolic Score for Insulin Resistance and Hypertension in Adults: A Meta-Analysis. Horm. Metab. Res. 2023, 55, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Han, L.; Hu, D. Fasting insulin, insulin resistance and risk of hypertension in the general population: A meta-analysis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2017, 464, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xun, P.; Liu, K.; Cao, W.; Sidney, S.; Williams, O.D.; He, K. Fasting insulin level is positively associated with incidence of hypertension among American young adults: A 20-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 1532–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, F.; Yu, Z. Mendelian randomization study on insulin resistance and risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ferrannini, E.; Haffner, S.M.; Stern, M.P. Essential hypertension: An insulin-resistant state. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1990, 15 (Suppl. S5), S18–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrie, J.R.; Malik, M.O.; Balkau, B.; Perry, C.G.; Højlund, K.; Pataky, Z.; Nolan, J.; Ferrannini, E.; Natali, A. RISC Investigators. Euglycemic clamp insulin sensitivity and longitudinal systolic blood pressure: Role of sex. Hypertension 2013, 62, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofland, J.; Refardt, J.C.; Feelders, R.A.; Christ, E.; de Herder, W.W. Approach to the Patient: Insulinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sarafidis, P.A.; Ruilope, L.M. Insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and renal injury: Mechanisms and implications. Am. J. Nephrol. 2006, 26, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, S.A.; Dubourg, J.; Knott, M.; Colca, J. Hyperinsulinemia, an overlooked clue and potential way forward in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Hepatology 2023. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunelli, C.; Spallarossa, P.; Cordera, R.; Caponnetto, S. Iperinsulinemia e rischio cardiovascolare [Hyperinsulinemia and cardiovascular risk]. Cardiologia 1994, 39 (Suppl. S1), 163–168. (In Italian) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

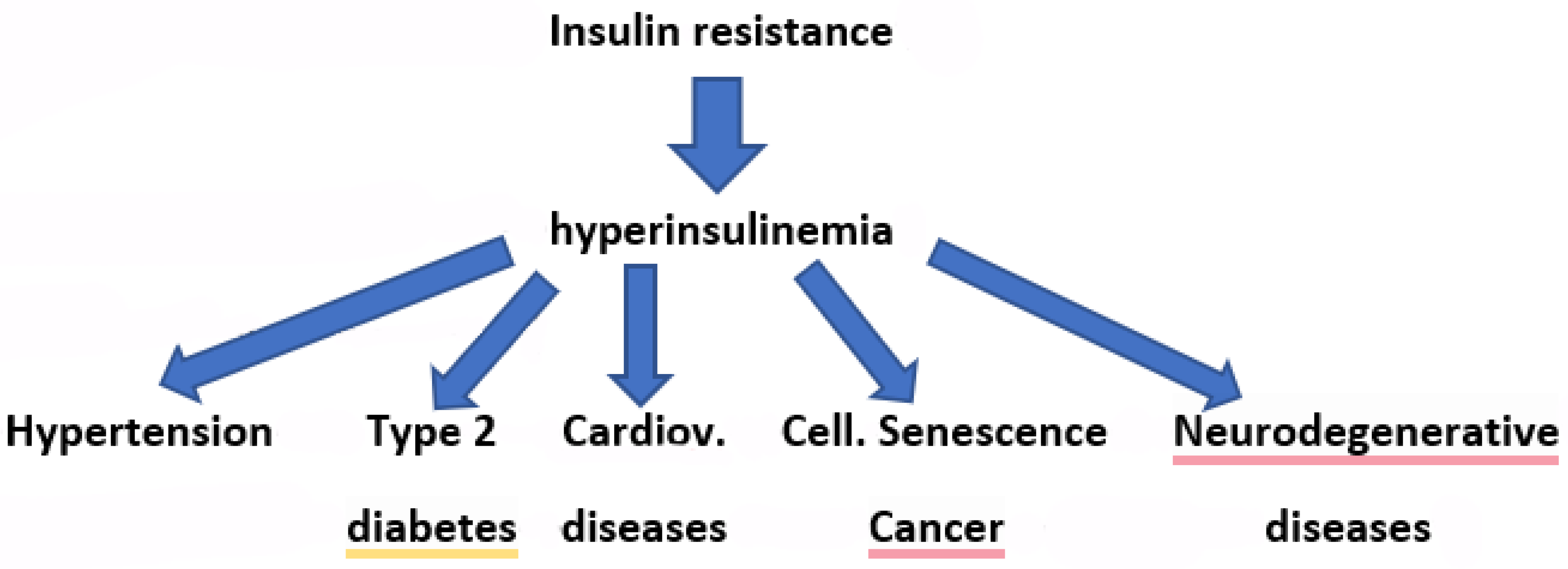

- Fazio, S.; Fazio, V.; Affuso, F. The link between insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia and increased mortality risk. Acad. Med. Health 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, S.; Bellavite, P.; Affuso, F. Chronically Increased Levels of Circulating Insulin Secondary to Insulin Resistance: A Silent Killer. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazio, S.; Affuso, F.; Cesaro, A.; Tibullo, L.; Fazio, V.; Calabrò, P. Insulin Resistance/Hyperinsulinemia as an Independent Risk Factor that Has Been Overlooked for Too Long. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potenza, M.A.; Marasciulo, F.L.; Chieppa, D.M.; Brigiani, G.S.; Formoso, G.; Quon, M.J.; Montagnani, M. Insulin resistance in spontaneously hypertensive rats is associated with endothelial dysfunction characterized by imbalance between NO and ET-1 production. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005, 289, H813–H822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamami, Y.; Takatori, S.; Yamawaki, K.; Miyashita, S.; Mio, M.; Kitamura, Y.; Kawasaki, H. Acute hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia enhance adrenergic vasoconstriction and decrease calcitonin gene-related peptide-containing nerve-mediated vasodilation in pithed rats. Hypertens. Res. 2008, 31, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazidi, M.; Katsiki, N.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Banach, M. International Lipid Expert Panel (ILEP). Effect of Dietary Insulinemia on All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: Results From a Cohort Study. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2020, 39, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arauz-Pacheco, C.; Lender, D.; Snell, P.; Huet, B.; Ramirez, L.; Breen, L.; Mora, P.; Raskin, P. Relationship between insulin sensitivity, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin-mediated sympathetic activation in normotensive and hypertensive subjects. Am. J. Hypertens. 1996, 9 Pt 1, 1172–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semplicini, A.; Ceolotto, G.; Massimino, M.; Valle, R.; Serena, L.; De Toni, R.; Pessina, A.C.; Palù, C.D. Interactions between insulin and sodium homeostasis in essential hypertension. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1994, 307 (Suppl. S1), S43–S46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nizar, J.M.; Shepard, B.D.; Vo, V.T.; Bhalla, V. Renal tubule insulin receptor modestly promotes elevated blood pressure and markedly stimulates glucose reabsorption. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 3, e95107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McNulty, M.; Mahmud, A.; Feely, J. Advanced glycation end-products and arterial stiffness in hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2007, 20, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thethi, T.; Kamiyama, M.; Kobori, H. The link between the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and renal injury in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2012, 14, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Luther, J.M.; Brown, N.J. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and glucose homeostasis. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 32, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hill, D.J.; Milner, R.D. Insulin as a growth factor. Pediatr. Res. 1985, 19, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvetti, A.; Brogi, G.; Di Legge, V.; Bernini, G.P. The inter-relationship between insulin resistance and hypertension. Drugs 1993, 46 (Suppl. S2), 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjögren, K.; Liu, J.-L.; Blad, K.; Skrtic, S.; Vidal, O.; Wallenius, V.; LeRoith, D.; Törnell, J.; Isaksson, O.G.P.; Jansson, J.-O.; et al. Liver-derived insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) is the principal source of IGF-I in blood but is not required for postnatal body growth in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 7088–7092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gastaldelli, A. Measuring and estimating insulin resistance in clinical and research settings. Obesity 2022, 30, 1549–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chooi, Y.C.; Ding, C.; Magkos, F. The epidemiology of obesity. Metabolism 2019, 92, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefíková, K.; Spustová, V.; Jakubovská, Z.; Dzúrik, R. The prevalence of insulin resistance in essential hypertension. Cor Vasa 1993, 35, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lind, L.; Berne, C.; Lithell, H. Prevalence of insulin resistance in essential hypertension. J. Hypertens. 1995, 13 Pt 1, 1457–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, N.K.; Abbasi, F.; Lamendola, C.; Reaven, G.M. Prevalence of insulin resistance and related risk factors for cardiovascular disease in patients with essential hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2009, 22, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummen, M.; Adam, T.C.; Macdonald, I.A.; Jalo, E.; Larssen, T.M.; Martinez, J.A.; Handjiev-Darlenska, T.; Brand-Miller, J.; Poppitt, S.D.; Stratton, G.; et al. Associations of changes in reported and estimated protein and energy intake with changes in insulin resistance, glycated hemoglobin, and BMI during the PREVIEW lifestyle intervention study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 1847–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Herman, R.; Kravos, N.A.; Jensterle, M.; Janež, A.; Dolžan, V. Metformin and Insulin Resistance: A Review of the Underlying Mechanisms behind Changes in GLUT4-Mediated Glucose Transport. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chai, S.Y.; Zhang, R.Y.; Ning, Z.Y.; Zheng, Y.M.; Swapnil, R.; Ji, L.N. Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors improve insulin resistance and β-cell function in type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. World J. Diabetes 2025, 16, 107335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thomas, M.K.; Nikooienejad, A.; Bray, R.; Cui, X.; Wilson, J.; Duffin, K.; Milicevic, Z.; Haupt, A.; A Robins, D. Dual GIP and GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Tirzepatide Improves Beta-cell Function and Insulin Sensitivity in Type 2 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gong, M.; Duan, H.; Wu, F.; Ren, Y.; Gong, J.; Xu, L.; Lu, F.; Wang, D. Berberine Alleviates Insulin Resistance and Inflammation via Inhibiting the LTB4-BLT1 Axis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 722360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bellavite, P.; Fazio, S.; Affuso, F. A Descriptive Review of the Action Mechanisms of Berberine, Quercetin and Silymarin on Insulin Resistance/Hyperinsulinemia and Cardiovascular Prevention. Molecules 2023, 28, 4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hu, S.; Han, M.; Rezaei, A.; Li, D.; Wu, G.; Ma, X. L-Arginine Modulates Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Obesity and Diabetes. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2017, 18, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takada, M.; Sumi, M.; Maeda, A.; Watanabe, F.; Kamiya, T.; Ishii, T.; Nakano, M.; Akagawa, M. Pyrroloquinoline quinone, a novel protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitor, activates insulin signaling in C2C12 myotubes and improves impaired glucose tolerance in diabetic KK-A(y) mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 428, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efird, J.T.; Choi, Y.M.; Davies, S.W.; Mehra, S.; Anderson, E.J.; Katunga, L.A. Potential for improved glycemic control with dietary Momordica charantia in patients with insulin resistance and pre-diabetes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 2328–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tseng, C.H. Metformin Use Is Associated with a Lower Risk of Hospitalization for Heart Failure in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 2019, 8, e011640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Neuen, B.L.; Fletcher, R.A.; Heath, L.; Perkovic, A.; Vaduganathan, M.; Badve, S.V.; Tuttle, K.R.; Pratley, R.; Gerstein, H.C.; Perkovic, V.; et al. Cardiovascular, Kidney, and Safety Outcomes with GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Alone and in Combination with SGLT2 Inhibitors in Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circulation 2024, 150, 1781–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preda, A.; Montecucco, F.; Carbone, F.; Camici, G.G.; Lüscher, T.F.; Kraler, S.; Liberale, L. SGLT2 inhibitors: From glucose-lowering to cardiovascular benefits. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 120, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mullur, N.; Morissette, A.; Morrow, N.M.; Mulvihill, E.E. GLP-1 receptor agonist-based therapies and cardiovascular risk: A review of mechanisms. J. Endocrinol. 2024, 263, e240046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Iacobellis, G.; Baroni, M.G. Cardiovascular risk reduction throughout GLP-1 receptor agonist and SGLT2 inhibitor modulation of epicardial fat. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2022, 45, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamani, M.; Zarei, M.; Nikbaf-Shandiz, M.; Hosseini, S.; Shiraseb, F.; Asbaghi, O. The effects of berberine supplementation on cardiovascular risk factors in adults: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1013055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mariotti, F. Arginine supplementation and cardiometabolic risk. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2020, 23, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popiolek-Kalisz, J.; Fornal, E. The Impact of Flavonols on Cardiovascular Risk. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xing, X.Y.; Li, Y.F.; Fu, Z.D.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.F.; Liu, X.L.; Liu, W.Y.; Li, G.W. Antihypertensive effect of metformin in essential hypertensive patients with hyperinsulinemia. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2010, 49, 14–18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Maitz, T.; Egeler, D.; Mehta, A.; Nyaeme, M.; Hajra, A.; Goel, A.; Sreenivasan, J.; Patel, N.; Aronow, W.S. SGLT2 inhibitors in hypertension: Role beyond diabetes and heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 33, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; Wu, S.; Guo, S.; Yu, K.; Yang, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Quan, X.; Ji, L.; Zhan, S. Impact of GLP-1 receptor agonists on blood pressure, heart rate and hypertension among patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2015, 110, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, J.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, F.; Yan, Z.; Zheng, W.; Fan, J.; Sun, G. Meta-analysis of the effect and safety of berberine in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperlipemia and hypertension. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 161, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, W.T.; Sutopo, C.C.Y.; Mahatmanto, T.; Wu, M.L.; Hsu, J.L. Exploring the Antidiabetic and Antihypertensive Potential of Peptides Derived from Bitter Melon Seed Hydrolysate. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gokce, N. L-arginine and hypertension. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 2807S–2811S, discussion 2818S–2819S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, A.J.; Symons, J.D.; Jalili, T. Quercetin: A Treatment for Hypertension?—A Review of Efficacy and Mechanisms. Pharmaceuticals 2010, 3, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Greco, D.; Sinagra, D. Iperinsulinemia/insulinoresistenza: Causa, effetto o marker dell’ipertensione arteriosa essenziale? Hyperinsulinism/insulin resistance: Cause, effect or marker of essential arterial hypertension? G. Ital. Cardiol. 1995, 25, 207–216. (In Italian) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. HEALTH & WELLNESS. Understanding Insulin Resistance. Available online: https://diabetes.org/health-wellness/insulin-resistance (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Hill, M.A.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Z.; Jia, G.; Parrish, A.R.; Sowers, J.R. Insulin resistance, cardiovascular stiffening and cardiovascular disease. Metabolism 2021, 119, 154766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinelli, R.; Baboota, R.K.; Gogg, S.; Beguinot, F.; Blüher, M.; Nerstedt, A.; Smith, U. Increased cell senescence in human metabolic disorders. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e169922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Janssen, J.A.M.J.L. Hyperinsulinemia and Its Pivotal Role in Aging, Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schubert, M.; Gautam, D.; Surjo, D.; Ueki, K.; Baudler, S.; Schubert, D.; Kondo, T.; Alber, J.; Galldiks, N.; Küstermann, E.; et al. Role for neuronal insulin resistance in neurodegenerative diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 3100–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kellar, D.; Craft, S. Brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders: Mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mercurio, V.; Carlomagno, G.; Fazio, V.; Fazio, S. Insulin resistance: Is it time for primary prevention? World J. Cardiol. 2012, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fazio, S.; Affuso, F. Insulin Resistance/Hyperinsulinemia Should Be Considered in the Prevention and Treatment of Essential Hypertension. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3102. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123102

Fazio S, Affuso F. Insulin Resistance/Hyperinsulinemia Should Be Considered in the Prevention and Treatment of Essential Hypertension. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3102. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123102

Chicago/Turabian StyleFazio, Serafino, and Flora Affuso. 2025. "Insulin Resistance/Hyperinsulinemia Should Be Considered in the Prevention and Treatment of Essential Hypertension" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3102. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123102

APA StyleFazio, S., & Affuso, F. (2025). Insulin Resistance/Hyperinsulinemia Should Be Considered in the Prevention and Treatment of Essential Hypertension. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3102. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123102