1. Introduction

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) affects over 200 million individuals globally and represents a major source of cardiovascular morbidity and functional impairment, particularly among aging populations [

1]. In patients with chronic limb-threatening ischemia, endovascular revascularization is guideline-supported as an effective revascularization strategy, whereas in intermittent claudication, supervised exercise therapy and risk-factor optimization represent first-line therapy. Revascularization is reserved for patients with lifestyle-limiting symptoms that persist despite optimal conservative management [

2].

Historically, plain balloon angioplasty (POBA) was widely used but suffered from high rates of elastic recoil and restenosis, especially in long, calcified, or ostial lesions [

3]. The introduction of nitinol stents offered mechanical scaffolding to prevent recoil and flow-limiting dissection, improving early outcomes; however, in-stent restenosis (ISR) remained a persistent limitation [

4].

More recently, drug-coated balloons (DCBs) have been developed to deliver antiproliferative agents—typically paclitaxel—without leaving a permanent implant. These devices offer the theoretical advantage of reducing neointimal hyperplasia while avoiding the long-term risks associated with stent placement. Randomized controlled trials such as the IN.PACT SFA and PACIFIER trials demonstrated superior patency rates and lower target lesion revascularization (TLR) compared to standard balloon angioplasty [

5,

6].

Real-world data have since confirmed the effectiveness of DCBs in complex lesion subsets, with reported 1-year primary patency rates exceeding 75% in contemporary registries [

7]. Furthermore, comparative studies have begun to evaluate different DCB dosing strategies, suggesting non-inferiority of low-dose versus high-dose paclitaxel formulations in terms of restenosis and safety [

8,

9]. A recent systematic review of randomized trials supports the long-term efficacy and safety of paclitaxel-coated balloons in the femoropopliteal segment [

10].

Despite these advances, real-world decision-making in peripheral interventions remains highly heterogeneous. Operators choose between direct stenting, various stent optimization techniques, DCB ± bailout stenting, or POBA according to lesion morphology, vessel size, and procedural complexity rather than through standardized algorithms. As a result, comparative data on how these routinely used strategies influence restenosis risk in unselected PAD populations remain limited.

The aim of this study was therefore to evaluate the association between DCB-based angioplasty and 1-year restenosis, compared with stent-based and plain balloon strategies, in a real-world cohort of patients undergoing lower limb endovascular revascularization for symptomatic PAD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

We conducted a single-center retrospective cohort study including all consecutive patients who underwent endovascular revascularization for symptomatic lower limb PAD between January 2010 and December 2023 at Claude Galien Hospital, Institut Cardiovasculaire Paris-Sud, France. Patients were eligible if they received percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) with at least one of the following strategies: (1) direct stent implantation, (2) pre-dilatation followed by stenting, (3) stenting with post-dilatation, (4) DCB with or without bailout stenting, or (5) POBA without stenting or drug application.

Stent-based strategy subcategories were defined according to whether lesion predilatation and/or post-dilatation were documented as separate procedural steps in the institutional registry. Because these steps were not systematically captured across the entire study period, their absence in the database does not necessarily indicate that they were not performed. Bailout stenting was defined as unplanned stent implantation following balloon angioplasty due to suboptimal angiographic results, including significant residual stenosis or flow-limiting dissection.

Patients were excluded if they underwent surgical bypass or lacked follow-up imaging data. All procedures were performed by four experienced interventionalists using standard femoral or radial access and fluoroscopic guidance, following institutional protocols. The choice of angioplasty strategy was left to the operator and was primarily guided by lesion morphology, vessel size, and device availability. Thus, the present analysis reflects consistent practice patterns within a single medium-volume center rather than sporadic procedures performed by low-experience operators. The patient selection process is summarized in

Figure 1.

2.2. Data Collection

Demographic data, cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., diabetes mellitus, smoking status, chronic kidney disease), lesion characteristics (length, diameter, calcification, chronic total occlusion), and procedural details (device type, balloon/stent characteristics) were prospectively recorded in a dedicated institutional database. In DCB-treated lesions, lesion preparation was performed according to standard clinical practice; however, predilatation was recorded only when documented as a separate procedural step, which may have resulted in underreporting of predilatation rates in the registry. Imaging follow-up at approximately 12 months was performed predominantly using duplex Doppler ultrasound as part of routine surveillance. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) or conventional angiography was reserved for selected cases, such as recurrent symptoms, inconclusive ultrasound findings, or when reintervention was being considered. The choice of follow-up imaging modality was based on clinical considerations and was not determined by the initial endovascular treatment strategy.

2.3. Study Endpoints

The primary endpoint was binary restenosis at 12 months, defined as ≥50% luminal diameter reduction by imaging. Secondary endpoints included procedural success, defined as residual stenosis < 30% without persistent flow-limiting dissection at the end of the procedure, and occurrence of access-site or periprocedural complications (bleeding or pseudoaneurysm). Persistent flow-limiting dissections were recorded only when present at the end of the procedure or when requiring additional unplanned intervention.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation, and categorical variables as counts and percentages. Comparisons between angioplasty strategy groups were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables, as appropriate. Restenosis-free survival was assessed using Kaplan-Meier estimates and compared using the log-rank test. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were constructed with careful consideration of model parsimony to avoid overfitting. Age, sex, and diabetes mellitus were selected a priori as key clinical covariates based on biological plausibility and data completeness. Lesion-related variables, including lesion length, reference vessel diameter, and calcification severity, were included based on their established association with restenosis risk and consistent availability in the dataset. Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

A total of 283 patients were included (mean age 67.7 ± 11.0 years; 79% male). The distribution of angioplasty strategies was: direct stent in 79 patients (27.9%), pre-dilatation + stent in 57 (20.1%), stent + post-dilatation in 54 (19.1%), DCB ± stent in 65 (23.0%), and POBA in 28 (9.9%). Baseline demographic characteristics and cardiovascular risk factors were well balanced across groups, with no significant differences in age, sex, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking history, or chronic kidney disease (all

p > 0.05) (

Table 1). Baseline clinical severity was assessed using Rutherford classification.

Lesion characteristics differed meaningfully between strategies. Lesion length was shortest in the DCB ± stent group (64.2 ± 22.5 mm) compared with the stent-based and POBA groups (72.8–81.9 mm; p = 0.04). Moderate-to-severe calcification was also less frequent in the DCB ± stent group (21.5% vs. 29.8–36.0%; p = 0.03). There were no significant differences in reference vessel diameter (p = 0.12) or prevalence of chronic total occlusion (p = 0.27).

3.2. Procedural Characteristics and Periprocedural Outcomes

Procedural steps reflected the predefined strategy categories (

Table 2). Pre-dilatation was performed in all patients in the pre-dilatation + stent group and in a minority of the other groups (

p < 0.001). Post-dilatation occurred in all patients in the stent + post-dilatation group and infrequently elsewhere (

p < 0.001). Bailout stenting was required in 18.5% of DCB ± stent procedures.

Overall procedural success was high (91.5%), with significant variation across strategies (

p = 0.02). The highest success rate was observed in the DCB ± stent group (96.8%), while the lowest was in the POBA group (82.1%). Periprocedural complications were uncommon (6.3%) and showed no significant differences between strategies (

p = 0.62). The most frequent events were access-site hematoma (2.5–7.1%) and pseudoaneurysm (0–3.6%). Persistent flow-limiting dissection (1.5–7.1%) was infrequent and was recorded only when present at the end of the procedure or requiring additional unplanned intervention. The distribution of lesion segments across treatment strategies is also shown in

Supplementary Materials Table S1.

3.3. Primary Endpoint: 12-Month Restenosis

Restenosis at 12 months occurred in 81 patients (28.7%). Restenosis rates differed significantly across strategies (

p = 0.004), with the lowest rate in the DCB ± stent group (15.4%) and the highest in the POBA group (38.1%). Stent-based strategies demonstrated intermediate rates (29.8–34.2%) (

Table 3).

Kaplan-Meier estimates showed that restenosis-free survival at 12 months was significantly higher with DCB ± stent (84.6%) than with stent-based strategies (65.1–68.2%) or POBA (61.9%), with an overall log-rank p = 0.002.

3.4. Adjusted Outcomes

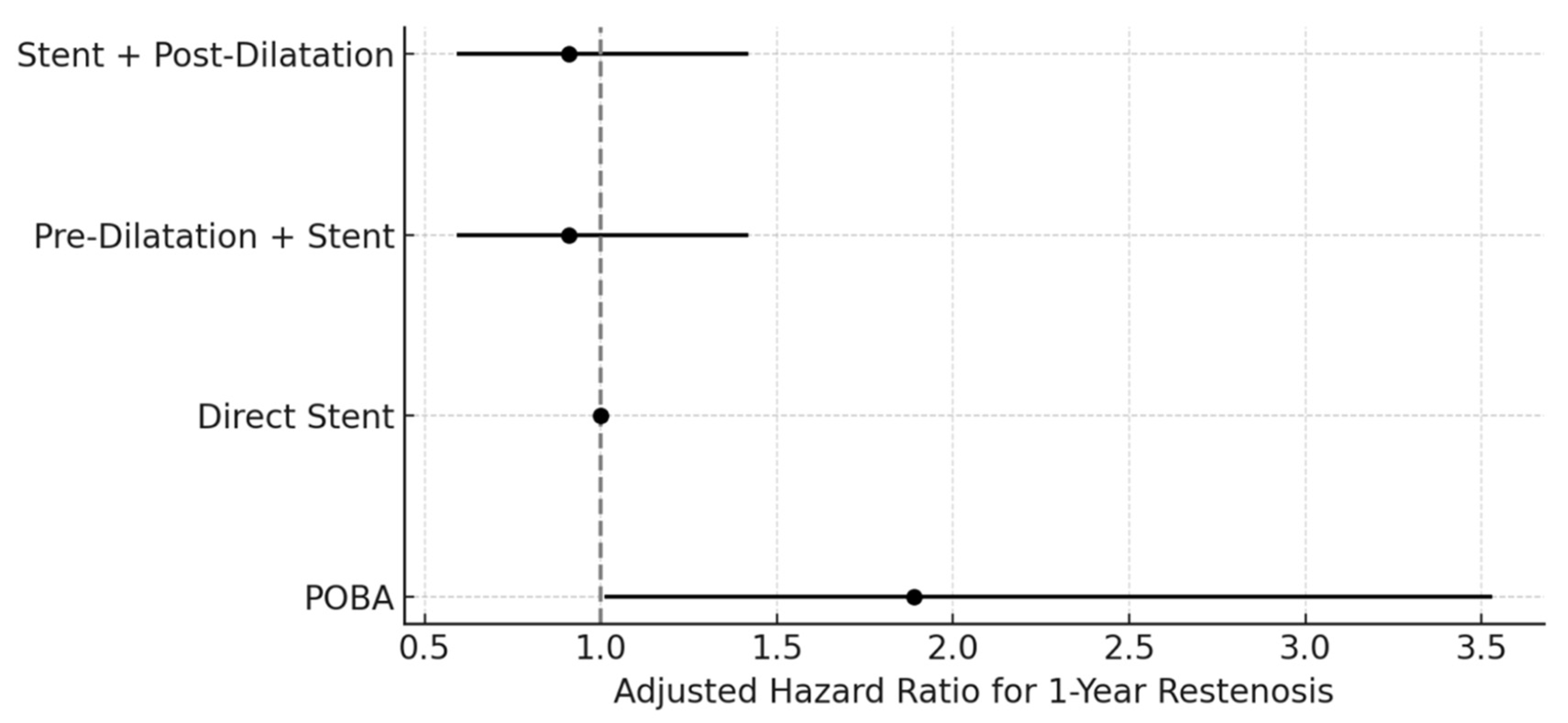

In the multivariable Cox regression model using direct stent as the reference, the DCB ± stent strategy was independently associated with a reduced risk of restenosis at 12 months (adjusted HR 0.52; 95% CI 0.31–0.87). Neither pre-dilatation + stent nor stent + post-dilatation differed significantly from direct stent (both adjusted HR 0.91; 95% CI 0.59–1.42) (

Figure 2). In the complementary model using DCB ± stent as the reference, POBA was associated with a higher hazard of restenosis (adjusted HR 1.89; 95% CI 1.01–3.53), while both stent-based strategies demonstrated no significant difference from DCB (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

In this real-world cohort of 283 patients undergoing endovascular revascularization for symptomatic PAD, we observed marked differences in 12-month restenosis between commonly used angioplasty strategies. The DCB ± stent group demonstrated the lowest restenosis rate at 15.4%, compared with 29.8–34.2% in the three stent-based strategies and 38.1% with POBA. These findings remained consistent after adjustment for key clinical and anatomical variables, with DCB therapy associated with a 48% lower hazard of restenosis relative to direct stenting (adjusted HR 0.52; 95% CI 0.31–0.87). Conversely, POBA was associated with nearly a two-fold higher hazard of restenosis compared with the DCB strategy (adjusted HR 1.89; 95% CI 1.01–3.53).

These observations align with the established evidence base supporting paclitaxel-coated balloon therapy. Randomized trials such as IN.PACT SFA and PACIFIER [

5,

6] demonstrated higher primary patency and lower target lesion revascularization with DCB therapy compared with standard PTA. Reported 1-year restenosis or loss-of-patency rates in DCB arms of major trials typically range from 12% to 20%, a range that is highly consistent with the 15.4% observed in our cohort. Likewise, long-term outcomes from pooled analyses and meta-analyses [

7,

8,

9,

10] have shown sustained reduction in neointimal hyperplasia with antiproliferative drug delivery.

However, unlike previous randomized studies that compare DCB therapy to a single control device, our analysis evaluated five distinct operator-selected strategies, reflecting the heterogeneity of routine clinical practice. This design allowed comparison not only between DCB and POBA, but also among commonly used stent-based approaches. The similar restenosis rates observed across direct stenting, pre-dilatation + stenting, and stent + post-dilatation (29.8–34.2%) suggest that, in this population, mechanical optimization maneuvers alone may have limited ability to meaningfully modify long-term vessel healing in the absence of drug delivery.

Procedural success exceeded 89% across all stent-based strategies and was highest in the DCB ± stent group (96.8%), indicating that DCB use did not compromise acute technical success. Periprocedural complications were infrequent across all strategies (6.3% overall), reinforcing the procedural safety of the approaches examined. Although lesions treated with DCB were somewhat shorter, the magnitude and consistency of benefit across both unadjusted and adjusted analyses suggest that this difference alone is unlikely to fully explain the observed outcomes.

Overall, these findings support the clinical relevance of antiproliferative therapy in optimizing long-term patency following peripheral angioplasty, while highlighting the limited incremental effect of stent optimization techniques on restenosis in real-world practice.

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective, observational design introduces the potential for selection bias, as strategy choice was operator-dependent and influenced by lesion characteristics and procedural complexity. Although multivariable adjustment was performed, unmeasured confounding cannot be excluded. Second, the analysis reflects the experience of a single medium-volume center, which may limit external generalizability. Practice patterns, device selection, and thresholds for bailout stenting may vary across institutions, particularly in higher-volume centers with broader access to advanced technologies. Third, the sample size, particularly for the POBA group (n = 28), is modest. While statistical significance was reached for the primary comparisons, the study may be underpowered to detect smaller differences between individual stent-based techniques or to support detailed subgroup analyses. Fourth, although all patients underwent imaging follow-up at 12 months, different modalities (duplex ultrasound, CTA, or angiography) were used. These modalities have differing sensitivities and specificities for detecting ≥50% restenosis. While the choice of imaging was driven by clinical indications rather than treatment strategy, this heterogeneity may have introduced some degree of restenosis misclassification. Detailed data on post-procedural antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy were not systematically available and could therefore not be included. Although all procedures were performed by experienced operators, the overall annual volume of femoropopliteal and infrapopliteal interventions was modest, and outcomes from very high-volume centers may differ. Finally, procedural variables such as balloon inflation pressure, stent expansion indices, and plaque composition were not systematically recorded. These technical factors may affect restenosis risk, but could not be incorporated into the adjusted models.

5. Conclusions

In this real-world single-center cohort of patients undergoing endovascular treatment for symptomatic PAD, DCB-based angioplasty was associated with a lower risk of restenosis compared with stent-based strategies and plain balloon angioplasty. Stent optimization techniques, including pre- and post-dilatation, did not meaningfully alter long-term patency within this population. These findings support the role of drug-coated balloon therapy as an effective strategy when anatomically feasible, while recognizing that individual lesion characteristics and procedural requirements may still necessitate stent deployment. Given the retrospective nature and single-center setting of this study, confirmation from larger, multicenter investigations is needed to clarify optimal treatment selection and to guide evidence-based decision-making in contemporary peripheral interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.S., L.D. and T.U.; methodology, I.S. and L.D.; software, I.S.; validation, I.S., L.D. and T.U.; formal analysis, I.S.; investigation, L.D., I.S., Y.L., F.S., A.N., H.B., B.H., A.S., N.S., P.L., N.A., T.H., P.G., M.A., S.C. and T.U.; resources, T.U. and L.D.; data curation, L.D. and I.S.; writing—original draft preparation, I.S.; writing—review and editing, I.S., L.D., T.U., M.A. and P.G.; visualization, I.S.; supervision, T.U. and M.A.; project administration, T.U. and L.D.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received fundings from Ramsay Sante pour l’Enseignement et la Recherche (39 Rue Mstislav Rostropovitch 75017 Paris, France).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This retrospective observational analysis used anonymized data routinely collected at the Institut Cardiovasculaire Paris Sud (ICPS), Massy, France. In accordance with French regulations (Méthodologie de Réfé-rence MR-004; Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés, CNIL), analyses of retrospective anonymized data do not require study-specific Institutional Review Board approval, protocol code, or written informed consent. The institutional registry is declared under the CNIL MR-004 compliance framework, and patients are routinely informed that their anonymized data may be used for research purposes, with the right to opt out.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because this retrospective observational study exclusively used fully anonymized data collected during routine clinical care, involved no additional interventions or patient contact, and posed no additional risk to participants in accordance with CNIL MR-004 regulations.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are availavle on request from the corresponding author due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

Ioannis Skalidis is supported by grants from the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation and from the Professor Max Cloëtta Foundation. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CTA | Computed Tomography Angiography |

| CTO | Chronic Total Occlusion |

| DCB | Drug-Coated Balloon |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| ISR | In-Stent Restenosis |

| PAD | Peripheral Artery Disease |

| POBA | Plain Old Balloon Angioplasty |

| PTA | Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| TLR | Target Lesion Revascularization |

References

- Fowkes, F.G.R.; Rudan, D.; Rudan, I.; Aboyans, V.; Denenberg, J.O.; McDermott, M.M.; Norman, P.E.; Sampson, U.K.; Williams, L.J.; Mensah, G.A.; et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: A systematic review and analysis. Lancet 2013, 382, 1329–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conte, M.S.; Bradbury, A.W.; Kolh, P.; White, J.V.; Dick, F.; Fitridge, R.; Mills, J.L.; Ricco, J.-B.; Suresh, K.R.; Murad, M.H.; et al. Global vascular guidelines on the management of chronic limb-threatening ischemia. J. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 69, 3S–125S.e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krankenberg, H.; Schlüter, M.; Steinkamp, H. Nitinol Stent Implantation Versus Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty in Superficial Femoral Artery Lesions up to 10 cm in Length: The Femoral Artery Stenting Trial (FAST). J. Vasc. Surg. 2008, 47, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, J.R.; Katzen, B.T.; Scheinert, D.; Lammer, J.; Carpenter, J.; Buchbinder, M.; Dave, R.; Ansel, G.; Lansky, A.; Cristea, E.; et al. Nitinol Stent Implantation Versus Balloon Angioplasty for Lesions in the Superficial Femoral Artery and Proximal Popliteal Artery. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2010, 3, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepe, G.; Laird, J.; Schneider, P.; Brodmann, M.; Krishnan, P.; Micari, A.; Metzger, C.; Scheinert, D.; Zeller, T.; Cohen, D.J.; et al. Drug-Coated Balloon Versus Standard Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty for the Treatment of Superficial Femoral and Popliteal Peripheral Artery Disease. Circulation 2015, 131, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werk, M.; Albrecht, T.; Meyer, D.-R.; Ahmed, M.N.; Behne, A.; Dietz, U.; Eschenbach, G.; Hartmann, H.; Lange, C.; Schnorr, B.; et al. Paclitaxel-Coated Balloons Reduce Restenosis After Femoro-Popliteal Angioplasty. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2012, 5, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Hwang, D.; Yun, W.-S.; Huh, S.; Kim, H.-K. Effectiveness of Atherectomy and Drug-Coated Balloon Angioplasty in Femoropopliteal Disease: A Comprehensive Outcome Study. Vasc. Spéc. Int. 2024, 40, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakama, T.; Takahara, M.; Iwata, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Tobita, K.; Hayakawa, N.; Horie, K.; Mori, S.; Obunai, K.; Ohki, T. Low-Dose vs High-Dose Drug-Coated Balloon for Symptomatic Femoropopliteal Artery Disease. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2023, 16, 2655–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, S.; Schmidt, A.; Zeller, T.; Tepe, G.; Thieme, M.; Maiwald, L.; Schröder, H.; Euringer, W.; Popescu, C.; Brechtel, K.; et al. Low-Dose vs High-Dose Paclitaxel-Coated Balloons for Femoropopliteal Lesions. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 15, 2093–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Oria, M.; Mastrorilli, D.; Secemsky, E.; Behrendt, C.-A.; Veraldi, G.; DeMartino, R.; Mani, K.; Budtz-Lilly, J.; Scali, S.; Saab, F.; et al. Robustness of Longitudinal Safety and Efficacy After Paclitaxel-Based Endovascular Therapy for Treatment of Femoro-Popliteal Artery Occlusive Disease: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 101, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).