Unraveling the Shared Genetic Architecture and Polygenic Overlap Between Loneliness, Major Depressive Disorder, and Sleep-Related Traits

Abstract

1. Introduction

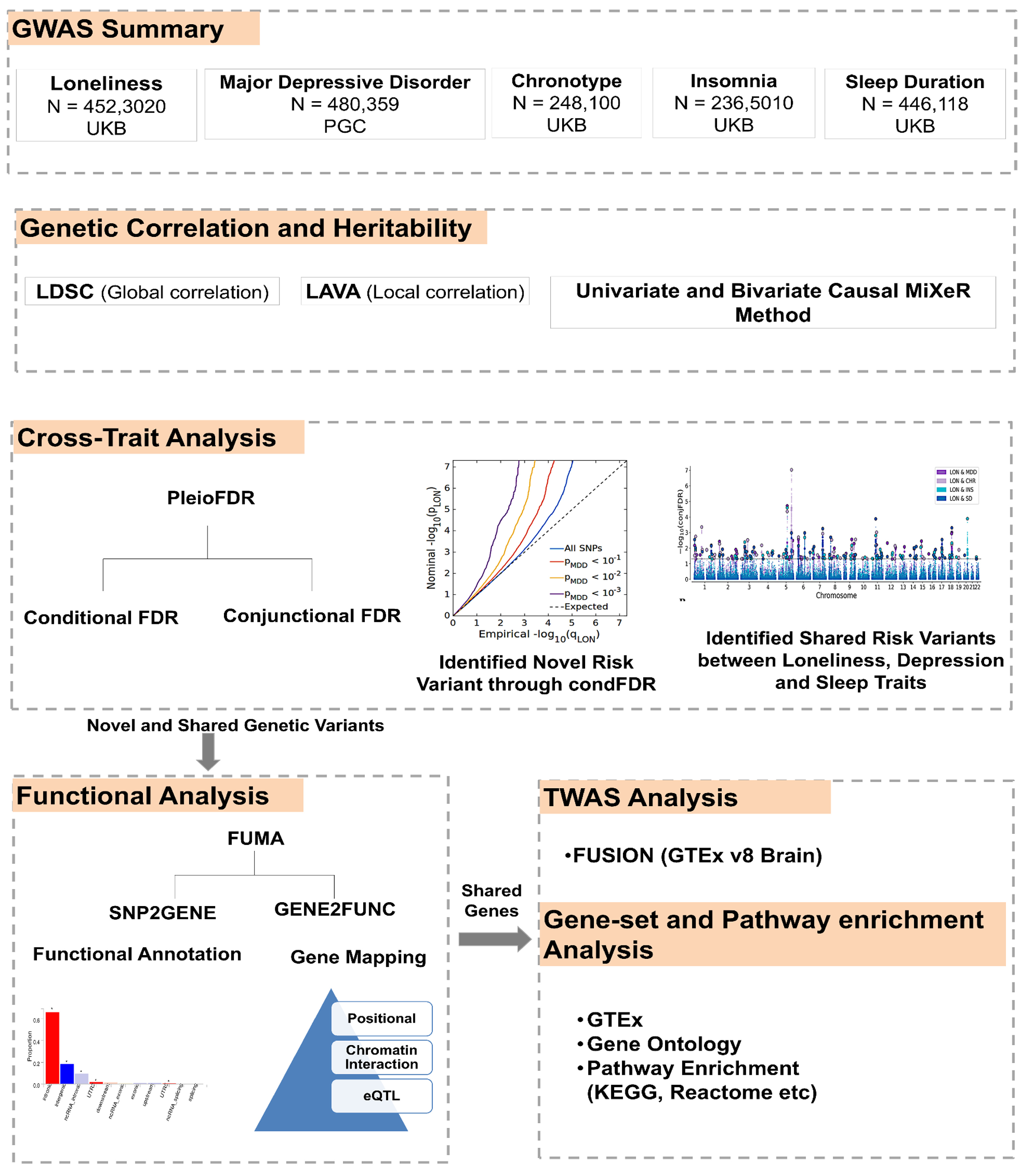

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample for GWAS Analysis

2.2. Statistical Analysis

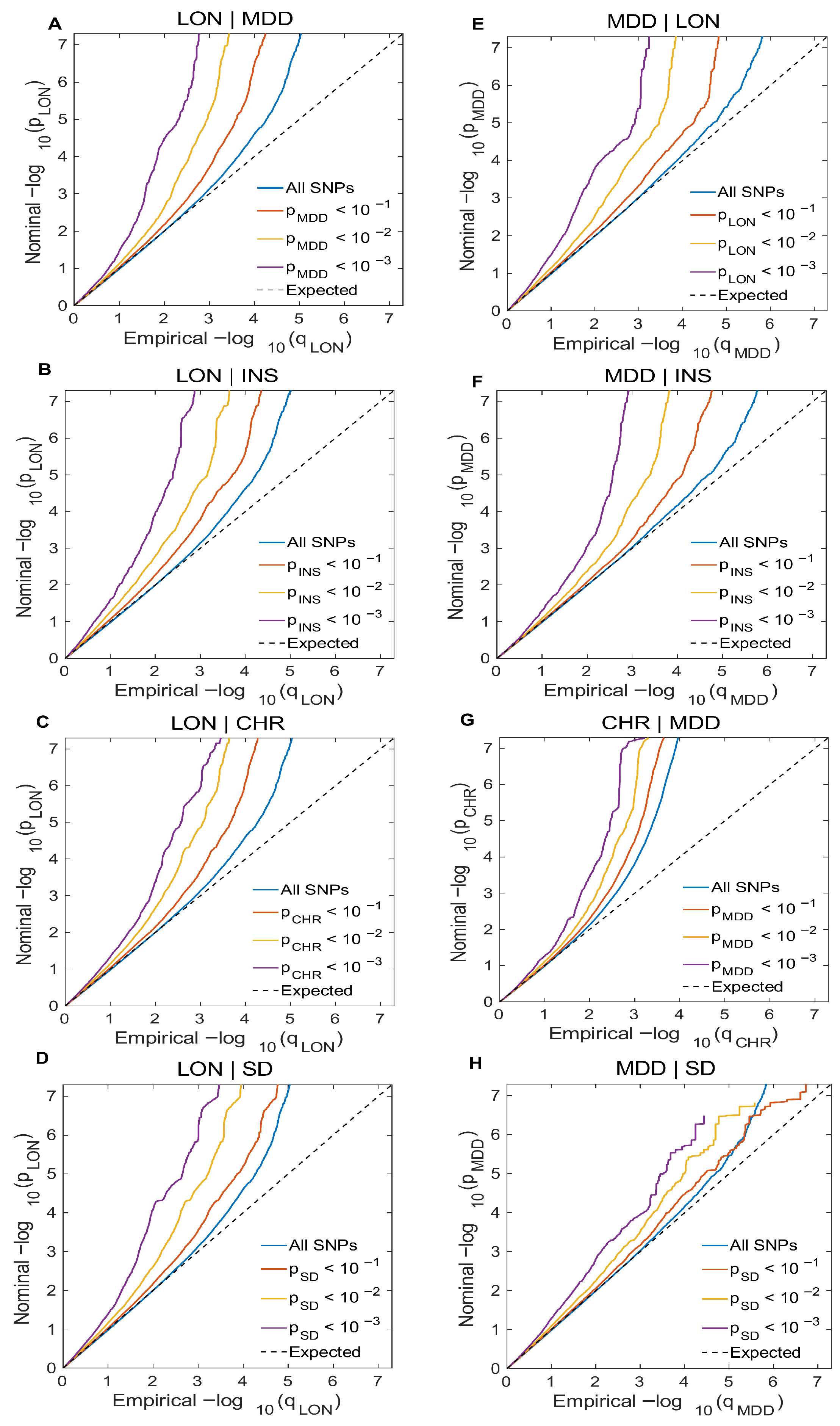

2.2.1. Conditional Q-Q Plot

2.2.2. Univariate and Bivariate Gaussian Causal MiXeR Method

2.2.3. Effect Direction, Genetic Heritability, and Genetic Correlation Using LDSC and LAVA

2.2.4. Conditional/Conjunctional False Discovery Rate (CondFDR/ConjFDR) Method

2.2.5. Defining Genomic Loci

2.3. Functional Annotation

2.4. Transcriptome-Wide Association Study (TWAS)

2.5. Software and Packages

2.6. Ethical Statement

3. Results

3.1. Cross-Trait Enrichment Pattern Analysis

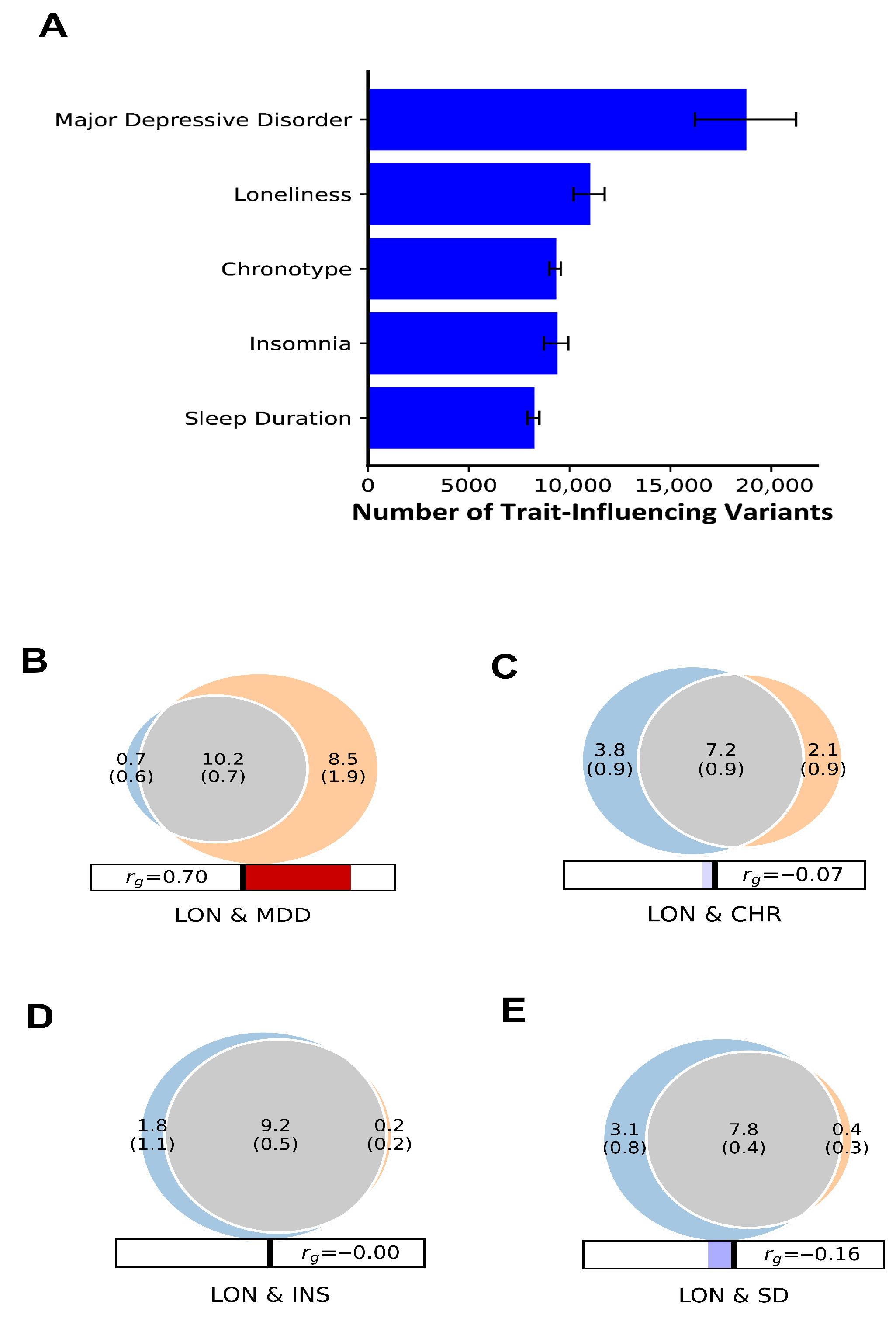

3.2. Genetic Overlap Quantification and Polygenicity Between LON, MDD, and Sleep Traits Using Univariate and Bivariate Causal MiXeR Method

3.3. Genetic Correlation and Effect Directions

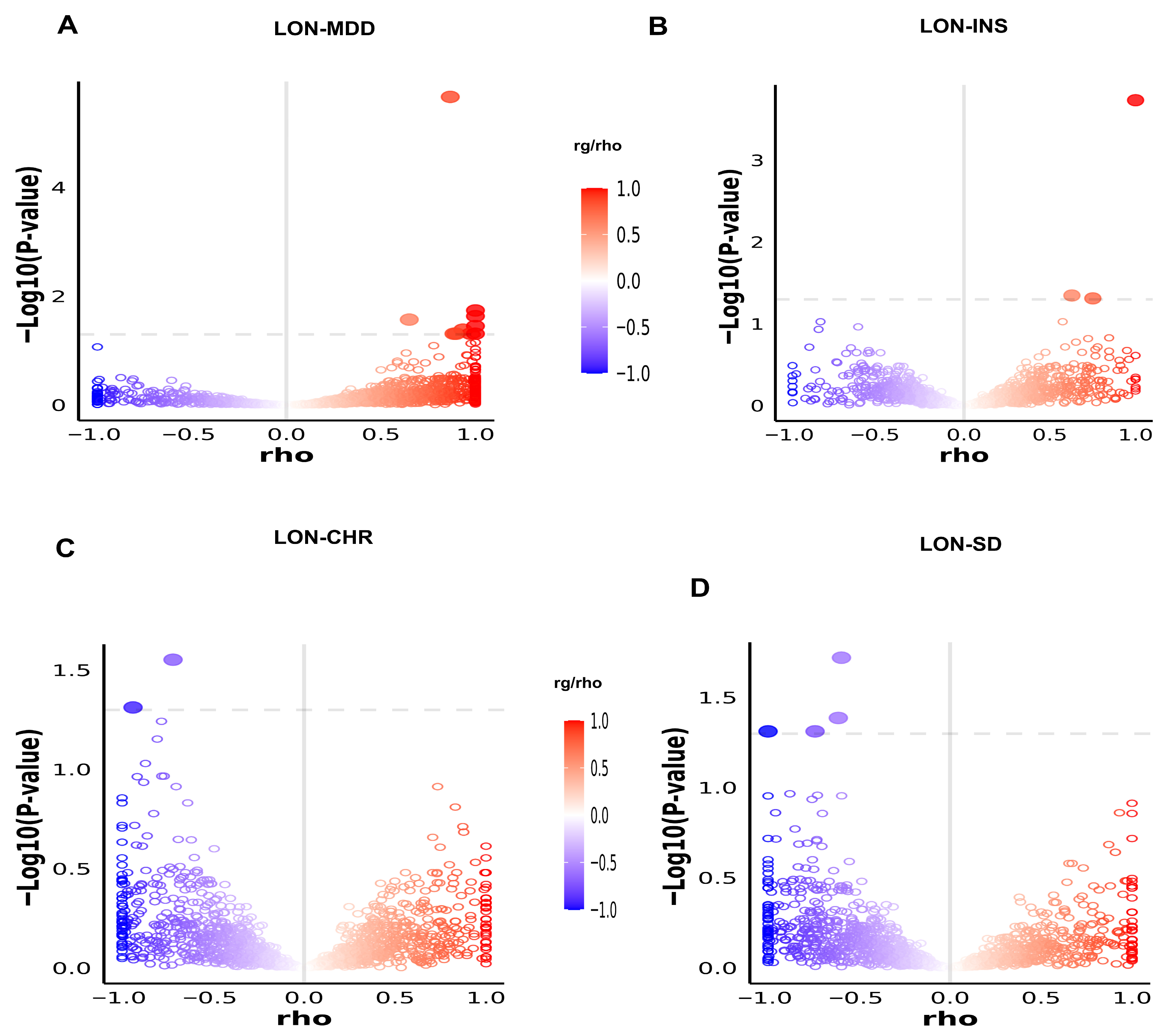

3.4. Local Genetic Correlation Through LAVA Analysis

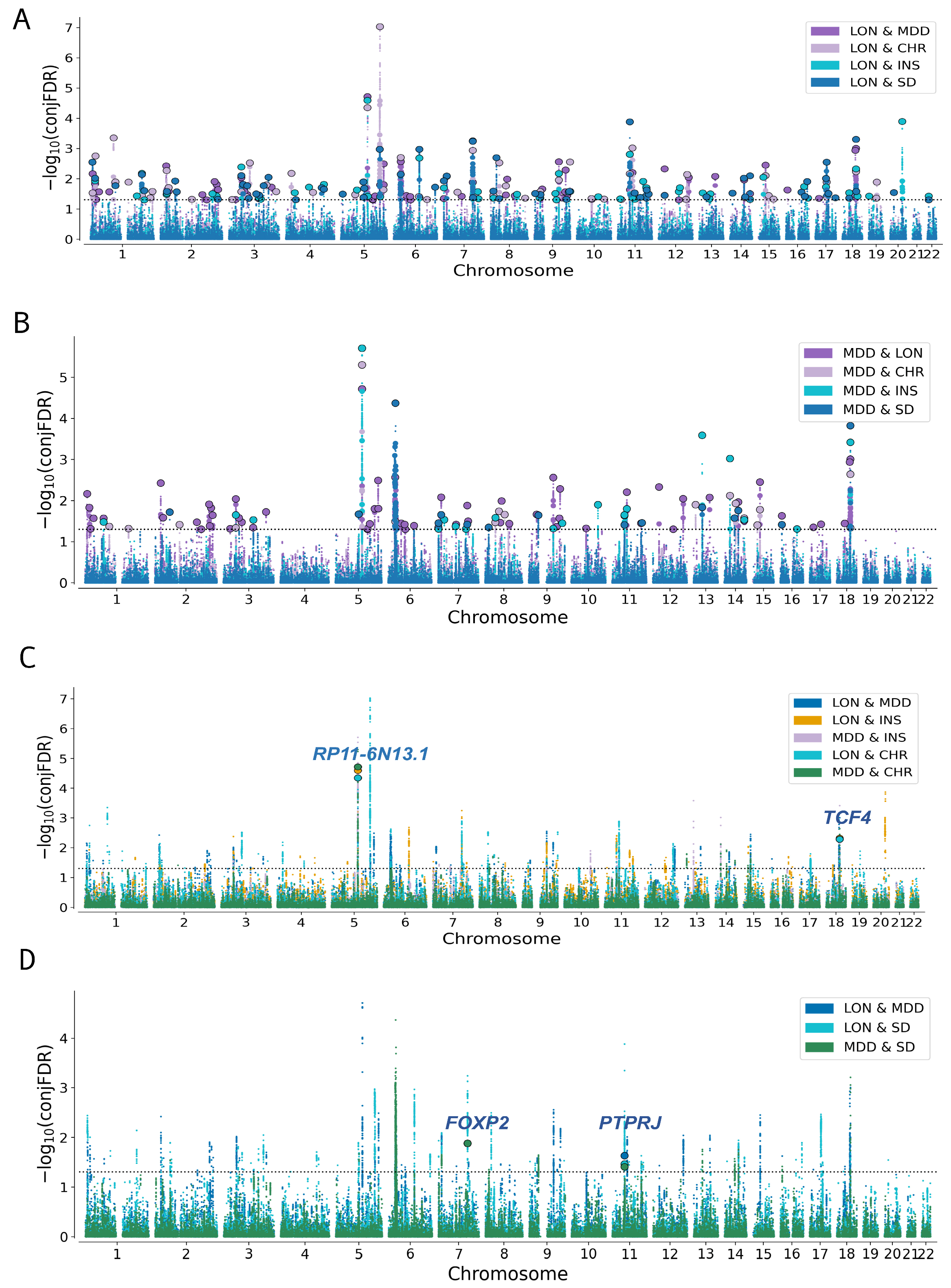

3.5. Association of Genomic Loci with LON, MDD and Sleep-Related Traits

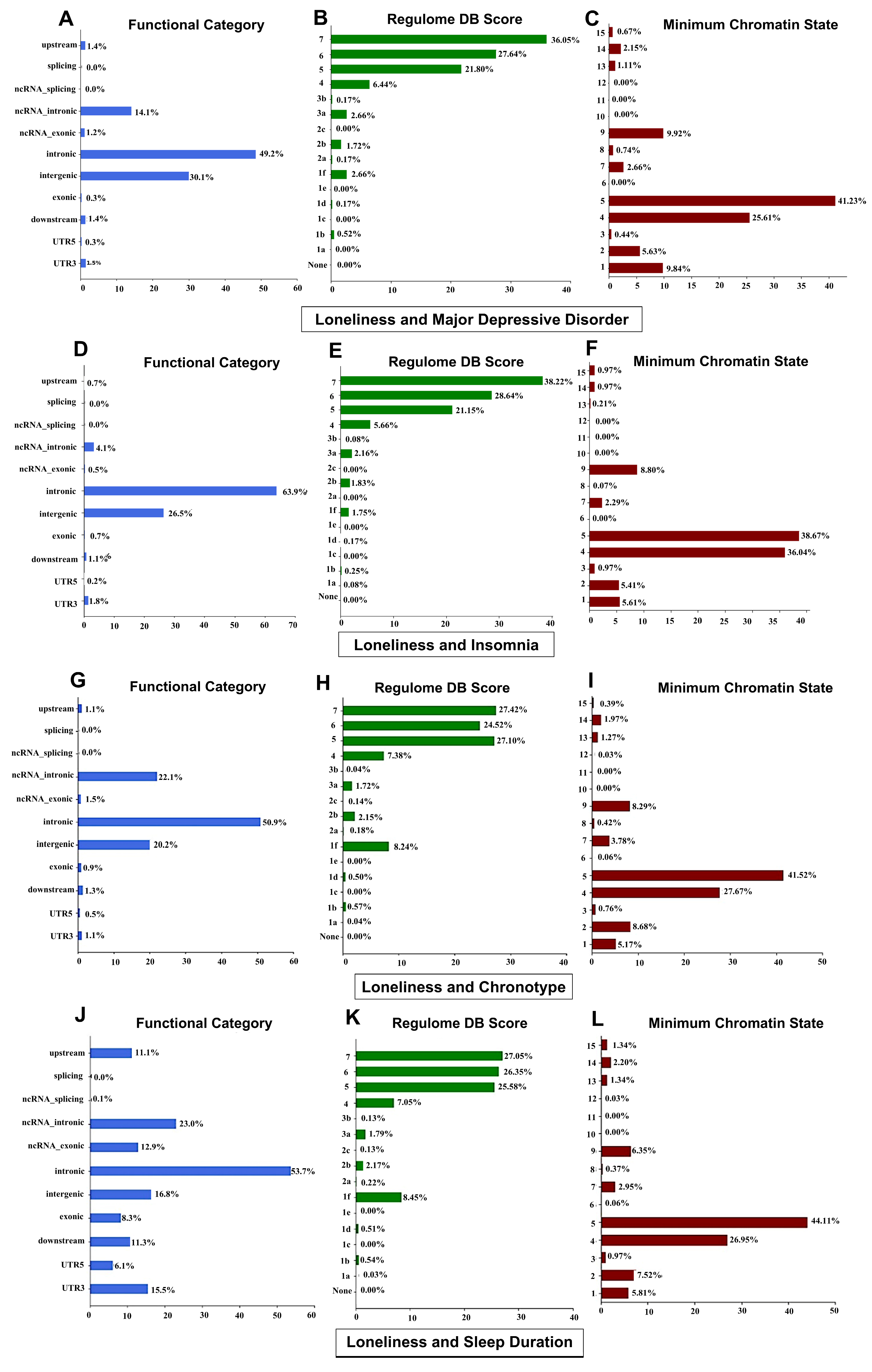

3.6. Functional Annotations of Genetic Loci

3.7. Gene Mapping and Gene-Set Enrichment Analysis

3.8. TWAS Identified Brain-Expressed Genes with Cross-Trait Overlap

3.9. Pathway Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LDSC | Linkage disequilibrium score regression |

| LAVA | Local Analysis of [co]Variant Association |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association studies |

| FUMA | Functional mapping and annotation |

| TWAS | Transcriptome-wide association studies |

| CondFDR/ConjFDR | Conditional/conjunctional false discovery rate |

| MHC | Major histocompatibility complex |

| GTEx | Genotype-tissue expression |

| rg | Genetic correlation |

| LON | Loneliness |

| MDD | Major depressive disorder |

| INS | Insomnia |

| CHR | Chronotype |

| SD | Sleep duration |

| AIC | Akaike information criterion |

| DC | Dice coefficient |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| CADD | Combined Annotation-Dependent Depletion |

| ANNOVAR | ANnotation of VARiants |

| RDB | Regulome database |

| LD | Linkage disequilibrium |

References

- Sbarra, D.A.; Ramadan, F.A.; Choi, K.W.; Treur, J.L.; Levey, D.F.; Wootton, R.E.; Stein, M.B.; Gelernter, J.; Klimentidis, Y.C. Loneliness and depression: Bidirectional mendelian randomization analyses using data from three large genome-wide association studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 4594–4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socrates, A.; Mullins, N.; Gur, R.; Gur, R.; Stahl, E.; O’Reilly, P.; Reichenberg, A.; Jones, H.; Zammit, S.; Velthorst, E. Polygenic risk of Social-isolation and its influence on social behavior, psychosis, depression and autism spectrum disorder. Res. Sq. 2023, rs.3.rs-2583059, [Version 1]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velthorst, E.; Froudist-Walsh, S.; Stahl, E.; Ruderfer, D.; Ivanov, I.; Buxbaum, J.; Banaschewski, T.; Bokde, A.L.; Dipl-Psych, U.B. Genetic risk for schizophrenia and autism, social impairment and developmental pathways to psychosis. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, L.; Liu, S.; Heim, C.; Heinz, A. The effects of social isolation stress and discrimination on mental health. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hawkley, L.C. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2003, 46, S39–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, L.J.; Smith, T.B.; Layton, B. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000316. [Google Scholar]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1218–1239. e1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellido-Zanin, G.; Pérez-San-Gregorio, M.Á.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Vázquez-Morejón, A.J. Social functioning as a predictor of the use of mental health resources in patients with severe mental disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 230, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Abella, J.; Mundó, J.; Haro, J.M.; Rubio-Valera, M. Anxiety, depression, loneliness and social network in the elderly: Longitudinal associations from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 246, 82–88, Erratum in J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 266, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenov, K.; Cabello, M.; Caballero, F.F.; Cieza, A.; Sabariego, C.; Raggi, A.; Anczewska, M.; Pitkänen, T.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L. Factors related to social support in neurological and mental disorders. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh-Hunt, N.; Bagguley, D.; Bash, K.; Turner, V.; Turnbull, S.; Valtorta, N.; Caan, W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health 2017, 152, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, T.; Danese, A.; Wertz, J.; Odgers, C.L.; Ambler, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L. Social isolation, loneliness and depression in young adulthood: A behavioural genetic analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.J.; Charlson, F.J.; Norman, R.E.; Patten, S.B.; Freedman, G.; Murray, C.J.; Vos, T.; Whiteford, H.A. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupfer, D.J.; Frank, E.; Phillips, M.L. Major depressive disorder: New clinical, neurobiological, and treatment perspectives. Lancet 2012, 379, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, J.; Kendler, K.S. The genetics of major depression. Neuron 2014, 81, 484–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoller, J.W.; Andreassen, O.A.; Edenberg, H.J.; Faraone, S.V.; Glatt, S.J.; Kendler, K.S. Psychiatric genetics and the structure of psychopathology. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 409–420, Erratum in Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P.F.; Neale, M.C.; Kendler, K.S. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: Review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 1552–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Davis, L.K.; Hart, A.B.; Sanchez-Roige, S.; Han, L.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Palmer, A.A. Genome-wide association study of loneliness demonstrates a role for common variation. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, F.R.; Ong, K.K.; Perry, J.R. Elucidating the genetic basis of social interaction and isolation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, B.; Kelsoe, J.R.; Sklar, P.; Daly, M.J.; O’Donovan, M.C.; Craddock, N.; Sullivan, P.F.; Smoller, J.W.; Kendler, K.S. Genetic relationship between five psychiatric disorders estimated from genome-wide SNPs. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 984–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.G.; Murray, G.; Chandler, R.A.; Soehner, A. Sleep disturbance as transdiagnostic: Consideration of neurobiological mechanisms. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann, D.; Krone, L.B.; Wulff, K.; Nissen, C. Sleep, insomnia, and depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 45, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglioni, C.; Battagliese, G.; Feige, B.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Nissen, C.; Voderholzer, U.; Lombardo, C.; Riemann, D. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 135, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, J.M.; Jones, S.E.; Dashti, H.S.; Wood, A.R.; Aragam, K.G.; van Hees, V.T.; Strand, L.B.; Winsvold, B.S.; Wang, H.; Bowden, J. Biological and clinical insights from genetics of insomnia symptoms. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, C.M.; Benca, R. Chronic insomnia. Lancet 2012, 379, 1129–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merikanto, I.; Kronholm, E.; Peltonen, M.; Laatikainen, T.; Vartiainen, E.; Partonen, T. Circadian preference links to depression in general adult population. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 188, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, K.J.; Jaksa, A.A.; Eisengart, J.B.; Baron, K.G.; Lu, B.; Kane, P.; Kang, J.; Zee, P.C. Systematic evaluation of Axis-I DSM diagnoses in delayed sleep phase disorder and evening-type circadian preference. Sleep Med. 2012, 13, 1171–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivertsen, B.; Krokstad, S.; Øverland, S.; Mykletun, A. The epidemiology of insomnia: Associations with physical and mental health.: The HUNT-2 study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2009, 67, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammerschlag, A.R.; Stringer, S.; De Leeuw, C.A.; Sniekers, S.; Taskesen, E.; Watanabe, K.; Blanken, T.F.; Dekker, K.; Te Lindert, B.H.; Wassing, R. Genome-wide association analysis of insomnia complaints identifies risk genes and genetic overlap with psychiatric and metabolic traits. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 1584–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Shmygelska, A.; Tran, D.; Eriksson, N.; Tung, J.Y.; Hinds, D.A. GWAS of 89,283 individuals identifies genetic variants associated with self-reporting of being a morning person. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.E.; Tyrrell, J.; Wood, A.R.; Beaumont, R.N.; Ruth, K.S.; Tuke, M.A.; Yaghootkar, H.; Hu, Y.; Teder-Laving, M.; Hayward, C. Genome-wide association analyses in 128,266 individuals identifies new morningness and sleep duration loci. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wray, N.R.; Ripke, S.; Mattheisen, M.; Trzaskowski, M.; Byrne, E.M.; Abdellaoui, A.; Adams, M.J.; Agerbo, E.; Air, T.M.; Andlauer, T.M. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, K.; Jansen, P.R.; Savage, J.E.; Nandakumar, P.; Wang, X.; Hinds, D.A.; Gelernter, J.; Levey, D.F.; Polimanti, R. Genome-wide meta-analysis of insomnia prioritizes genes associated with metabolic and psychiatric pathways. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.E.; Lane, J.M.; Wood, A.R.; van Hees, V.T.; Tyrrell, J.; Beaumont, R.N.; Jeffries, A.R.; Dashti, H.S.; Hillsdon, M.; Ruth, K.S. Genome-wide association analyses of chronotype in 697,828 individuals provides insights into circadian rhythms. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashti, H.S.; Jones, S.E.; Wood, A.R.; Lane, J.M.; Van Hees, V.T.; Wang, H.; Rhodes, J.A.; Song, Y.; Patel, K.; Anderson, S.G. Genome-wide association study identifies genetic loci for self-reported habitual sleep duration supported by accelerometer-derived estimates. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rødevand, L.; Bahrami, S.; Frei, O.; Lin, A.; Gani, O.; Shadrin, A.; Smeland, O.B.; Connell, K.S.O.; Elvsåshagen, T.; Winterton, A. Polygenic overlap and shared genetic loci between loneliness, severe mental disorders, and cardiovascular disease risk factors suggest shared molecular mechanisms. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, K.S.; Frei, O.; Bahrami, S.; Smeland, O.B.; Bettella, F.; Cheng, W.; Chu, Y.; Hindley, G.; Lin, A.; Shadrin, A. Characterizing the genetic overlap between psychiatric disorders and sleep-related phenotypes. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 90, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, C.Q.; Zhu, T.; Zhu, F.; Jin, Y.L.; Zhang, W.S.; Xu, L. Associations Between Sleep Traits and Social Isolation: Observational and Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2024, 79, glad233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulik-Sullivan, B.K.; Loh, P.-R.; Finucane, H.K.; Ripke, S.; Yang, J.; Patterson, N.; Daly, M.J.; Price, A.L.; Neale, B.M. LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frei, O.; Holland, D.; Smeland, O.B.; Shadrin, A.A.; Fan, C.C.; Maeland, S.; O’Connell, K.S.; Wang, Y.; Djurovic, S.; Thompson, W.K. Bivariate causal mixture model quantifies polygenic overlap between complex traits beyond genetic correlation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hindley, G.; Frei, O.; Shadrin, A.A.; Cheng, W.; O’Connell, K.S.; Icick, R.; Parker, N.; Bahrami, S.; Karadag, N.; Roelfs, D. Charting the landscape of genetic overlap between mental disorders and related traits beyond genetic correlation. Am. J. Psychiatry 2022, 179, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werme, J.; van der Sluis, S.; Posthuma, D.; de Leeuw, C.A. An integrated framework for local genetic correlation analysis. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Meer, D.; Hindley, G.; Shadrin, A.A.; Smeland, O.B.; Parker, N.; Dale, A.M.; Frei, O.; Andreassen, O.A. Mapping the genetic landscape of psychiatric disorders with the MiXeR toolset. Biol. Psychiatry 2025, 98, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, O.A.; Djurovic, S.; Thompson, W.K.; Schork, A.J.; Kendler, K.S.; O’Donovan, M.C.; Rujescu, D.; Werge, T.; van de Bunt, M.; Morris, A.P. Improved detection of common variants associated with schizophrenia by leveraging pleiotropy with cardiovascular-disease risk factors. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 92, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, O.A.; Thompson, W.K.; Dale, A.M. Boosting the power of schizophrenia genetics by leveraging new statistical tools. Schizophr. Bull. 2014, 40, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntané, G.; Farré, X.; Bosch, E.; Martorell, L.; Navarro, A.; Vilella, E. The shared genetic architecture of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and lifespan. Hum. Genet. 2021, 140, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Taskesen, E.; Van Bochoven, A.; Posthuma, D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusev, A.; Ko, A.; Shi, H.; Bhatia, G.; Chung, W.; Penninx, B.W.; Jansen, R.; De Geus, E.J.; Boomsma, D.I.; Wright, F.A. Integrative approaches for large-scale transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B. Large-Scale Inference: Empirical Bayes Methods for Estimation, Testing, and Prediction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Shadrin, A.A.; Frei, O.; Smeland, O.B.; Bettella, F.; O’Connell, K.S.; Gani, O.; Bahrami, S.; Uggen, T.K.; Djurovic, S.; Holland, D. Phenotype-specific differences in polygenicity and effect size distribution across functional annotation categories revealed by AI-MiXeR. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 4749–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, D.; Frei, O.; Desikan, R.; Fan, C.-C.; Shadrin, A.A.; Smeland, O.B.; Sundar, V.S.; Thompson, P.; Andreassen, O.A.; Dale, A.M. Beyond SNP heritability: Polygenicity and discoverability of phenotypes estimated with a univariate Gaussian mixture model. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1008612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, M.; Hakonarson, H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircher, M.; Witten, D.M.; Jain, P.; O’roak, B.J.; Cooper, G.M.; Shendure, J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, A.P.; Hong, E.L.; Hariharan, M.; Cheng, Y.; Schaub, M.A.; Kasowski, M.; Karczewski, K.J.; Park, J.; Hitz, B.C.; Weng, S. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundaje, A.; Meuleman, W.; Ernst, J.; Bilenky, M.; Yen, A.; Heravi-Moussavi, A.; Kheradpour, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Ziller, M.J. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature 2015, 518, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Hu, H.; Bakshi, A.; Robinson, M.R.; Powell, J.E.; Montgomery, G.W.; Goddard, M.E.; Wray, N.R.; Visscher, P.M. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacArthur, J.; Bowler, E.; Cerezo, M.; Gil, L.; Hall, P.; Hastings, E.; Junkins, H.; McMahon, A.; Milano, A.; Morales, J. The new NHGRI-EBI Catalog of published genome-wide association studies (GWAS Catalog). Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D896–D901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguet, F.; Brown, A.A.; Castel, S.E.; Davis, J.R.; He, Y.; Jo, B.; Mohammadi, P.; Park, Y.; Parsana, P.; Segrè, A.V.; et al. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature 2017, 550, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hawkley, L.C.; Thisted, R.A. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol. Aging 2010, 25, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 2010, 40, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, E.Y.; Waite, L.J. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2009, 50, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.L.; Ramaswami, G.; Hartl, C.; Mancuso, N.; Gandal, M.J.; De La Torre-Ubieta, L.; Pasaniuc, B.; Stein, J.L.; Geschwind, D.H. Genetic control of expression and splicing in developing human brain informs disease mechanisms. Cell 2019, 179, 750–771. e722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandal, M.J.; Haney, J.R.; Parikshak, N.N.; Leppa, V.; Ramaswami, G.; Hartl, C.; Schork, A.J.; Appadurai, V.; Buil, A.; Werge, T.M. Shared molecular neuropathology across major psychiatric disorders parallels polygenic overlap. Science 2018, 359, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, S.; Shadrin, A.; Frei, O.; O’Connell, K.S.; Bettella, F.; Krull, F.; Fan, C.C.; Røssberg, J.I.; Hindley, G.; Ueland, T. Genetic loci shared between major depression and intelligence with mixed directions of effect. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, S.; Steen, N.E.; Shadrin, A.; O’Connell, K.; Frei, O.; Bettella, F.; Wirgenes, K.V.; Krull, F.; Fan, C.C.; Dale, A.M. Shared genetic loci between body mass index and major psychiatric disorders: A genome-wide association study. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yin, X.; Man, L.; Hou, W.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Q.; Hui, L. From single nucleotide variations to genes: Identifying the genetic links between sleep and psychiatric disorders. Sleep 2025, 48, zsae209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeland, O.B.; Frei, O.; Shadrin, A.; O’Connell, K.; Fan, C.-C.; Bahrami, S.; Holland, D.; Djurovic, S.; Thompson, W.K.; Dale, A.M. Discovery of shared genomic loci using the conditional false discovery rate approach. Hum. Genet. 2020, 139, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranova, A.; Cao, H.; Zhang, F. Shared genetic liability and causal effects between major depressive disorder and insomnia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2022, 31, 1336–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Cai, X.; Wang, L.; Yi, F.; Liao, W.; Huang, R.; Fang, C.; Chen, J.; Zhou, J. Comparative proteomics of rat olfactory bulb reveal insights into susceptibility and resiliency to chronic-stress-induced depression or anxiety. Neuroscience 2021, 473, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clepce, M.; Gossler, A.; Reich, K.; Kornhuber, J.; Thuerauf, N. The relation between depression, anhedonia and olfactory hedonic estimates—A pilot study in major depression. Neurosci. Lett. 2010, 471, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breunig, J.J.; Silbereis, J.; Vaccarino, F.M.; Šestan, N.; Rakic, P. Notch regulates cell fate and dendrite morphology of newborn neurons in the postnatal dentate gyrus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 20558–20563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunney, B.G.; Bunney, W.E. Mechanisms of rapid antidepressant effects of sleep deprivation therapy: Clock genes and circadian rhythms. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ämmälä, A.-J.; Urrila, A.-S.; Lahtinen, A.; Santangeli, O.; Hakkarainen, A.; Kantojärvi, K.; Castaneda, A.E.; Lundbom, N.; Marttunen, M.; Paunio, T. Epigenetic dysregulation of genes related to synaptic long-term depression among adolescents with depressive disorder and sleep symptoms. Sleep Med. 2019, 61, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Monti, J.M.; Burman, D.; Karthikeyan, R.; BaHammam, A.S.; Spence, D.W.; Brown, G.M.; Narashimhan, M. Clarifying the role of sleep in depression: A narrative review. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciani, L.; Salinas, P.C. WNTs in the vertebrate nervous system: From patterning to neuronal connectivity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005, 6, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Xu, N.; Kong, L.; Sun, S.; Xu, X.; Jia, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z. The antidepressant roles of Wnt2 and Wnt3 in stress-induced depression-like behaviors. Transl. Psychiatry 2016, 6, e892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konopka, G.; Bomar, J.M.; Winden, K.; Coppola, G.; Jonsson, Z.O.; Gao, F.; Peng, S.; Preuss, T.M.; Wohlschlegel, J.A.; Geschwind, D.H. Human-specific transcriptional regulation of CNS development genes by FOXP2. Nature 2009, 462, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Kuo, H.-Y.; Bornschein, U.; Takahashi, H.; Chen, S.-Y.; Lu, K.-M.; Yang, H.-Y.; Chen, G.-M.; Lin, J.-R.; Lee, Y.-H. Foxp2 controls synaptic wiring of corticostriatal circuits and vocal communication by opposing Mef2c. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hawkley, L.C.; Ernst, J.M.; Burleson, M.; Berntson, G.G.; Nouriani, B.; Spiegel, D. Loneliness within a nomological net: An evolutionary perspective. J. Res. Pers. 2006, 40, 1054–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Cacioppo, S.; Capitanio, J.P.; Cole, S.W. The neuroendocrinology of social isolation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 733–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.; Garety, P.A.; Bebbington, P.E.; Smith, B.; Rollinson, R.; Fowler, D.; Kuipers, E.; Ray, K.; Dunn, G. Psychological investigation of the structure of paranoia in a non-clinical population. Br. J. Psychiatry 2005, 186, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeland, O.B.; Bahrami, S.; Frei, O.; Shadrin, A.; O’Connell, K.; Savage, J.; Watanabe, K.; Krull, F.; Bettella, F.; Steen, N.E. Genome-wide analysis reveals extensive genetic overlap between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and intelligence. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 844–853, Erratum in Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovieff, N.; Cotsapas, C.; Lee, P.H.; Purcell, S.M.; Smoller, J.W. Pleiotropy in complex traits: Challenges and strategies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013, 14, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B. Size, Power and False Discovery Rates. arXiv. 2007. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/0710.2245 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; De Bakker, P.I.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schork, A.J.; Wang, Y.; Thompson, W.K.; Dale, A.M.; Andreassen, O.A. New statistical approaches exploit the polygenic architecture of schizophrenia—implications for the underlying neurobiology. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2016, 36, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.Z.; Hov, J.R.; Folseraas, T.; Ellinghaus, E.; Rushbrook, S.M.; Doncheva, N.T.; Andreassen, O.A.; Weersma, R.K.; Weismüller, T.J.; Eksteen, B.; et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related disease regions identifies nine new risk loci for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, T.; Brett, M.; Andersson, J.; Wager, T.; Poline, J.-B. Valid conjunction inference with the minimum statistic. Neuroimage 2005, 25, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartzman, A.; Lin, X. The effect of correlation in false discovery rate estimation. Biometrika 2011, 98, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trait 1 | Trait 2 | % Proportion of LON Shared Variants with MDD and Sleep Traits | % Proportion of MDD and Sleep Traits Shared Variants with LON | DC Mean (%) | Concordance Mean (s.d) | Genetic Correlation Mean (s.d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LON | MDD | 93.5% | 54.5% | 69% | 0.96 (0.04) | 0.70 (0.01) |

| CHR | 66% | 98% | 71% | 0.46 (0.003) | −0.07 (0.01) | |

| INS | 83.5% | 98% | 90% | 0.49 (0.003) | −0.001 (0.01) | |

| SD | 71.5% | 95% | 82% | 0.44 (0.004) | −0.16 (0.01) |

| Primary Trait |Secondary Trait | Genomic Loci at CondFDR < 0.01 | Novel Variants in the Primary Trait | Primary Trait|Secondary Trait | Genomic Loci at CondFDR < 0.01 | Novel Variants in Primary Trait |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LON|MDD | 52 | 23 | MDD|LON | 27 | 15 |

| LON|INS | 43 | 31 | INS|LON | 35 | 09 |

| LON|CHR | 38 | 25 | CHR|LON | 274 | 102 |

| LON|SD | 45 | 34 | SD|LON | 136 | 67 |

| MDD|CHR | 10 | 03 | CHR|MDD | 262 | 90 |

| MDD|INS | 21 | 07 | INS|MDD | 35 | 10 |

| MDD|SD | 09 | 04 | SD|MDD | 123 | 57 |

| Ind. SNP Associated Traits | Credible Mapped Gene[s] | No. of Genes |

|---|---|---|

| LON, MDD, CHR, SD | WNT3, RP11-707O23.5, ARHGAP27, PLEKHM1, AC091132.1 | 05 |

| LON, CHR, SD | STH, KANSL1-AS1, ARL17B, SPPL2C, RP11-259G18.3, RP11-259G18.1, CRHR1-IT1, CRHR1 | 08 |

| LON, INS, CHR, SD | FAM180B | 01 |

| LON, MDD | CCDC71, KLHDC8B, TCTA n, DAG1 n | 04 |

| LON, INS | FOXP2, FAM120A n, MED27, SPI1, SLC39A13, PSMC3, FAM180B, MTCH2, CLP1, ZDHHC5, SYT1, CSE1L n, DDX27 n, ZNFX1 n | 14 |

| LON, CHR | FAM180B, ARHGAP27, MAPT-AS1, MAPT, RP11-669E14.6 | 05 |

| LON, SD | RC3H2, NUP160 n, ARHGAP27, PACRG n | 04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rehman, Z.; Khan, A.A.; Ye, J.; Ma, X.; Kuang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lan, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; et al. Unraveling the Shared Genetic Architecture and Polygenic Overlap Between Loneliness, Major Depressive Disorder, and Sleep-Related Traits. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3101. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123101

Rehman Z, Khan AA, Ye J, Ma X, Kuang Y, Wang Z, Lan Z, Zhao Q, Yang J, Zhang X, et al. Unraveling the Shared Genetic Architecture and Polygenic Overlap Between Loneliness, Major Depressive Disorder, and Sleep-Related Traits. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3101. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123101

Chicago/Turabian StyleRehman, Zainab, Abdul Aziz Khan, Jun Ye, Xianda Ma, Yifang Kuang, Ziying Wang, Zhaohui Lan, Qian Zhao, Jiarun Yang, Xu Zhang, and et al. 2025. "Unraveling the Shared Genetic Architecture and Polygenic Overlap Between Loneliness, Major Depressive Disorder, and Sleep-Related Traits" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3101. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123101

APA StyleRehman, Z., Khan, A. A., Ye, J., Ma, X., Kuang, Y., Wang, Z., Lan, Z., Zhao, Q., Yang, J., Zhang, X., Shen, S., & Li, W. (2025). Unraveling the Shared Genetic Architecture and Polygenic Overlap Between Loneliness, Major Depressive Disorder, and Sleep-Related Traits. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3101. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123101