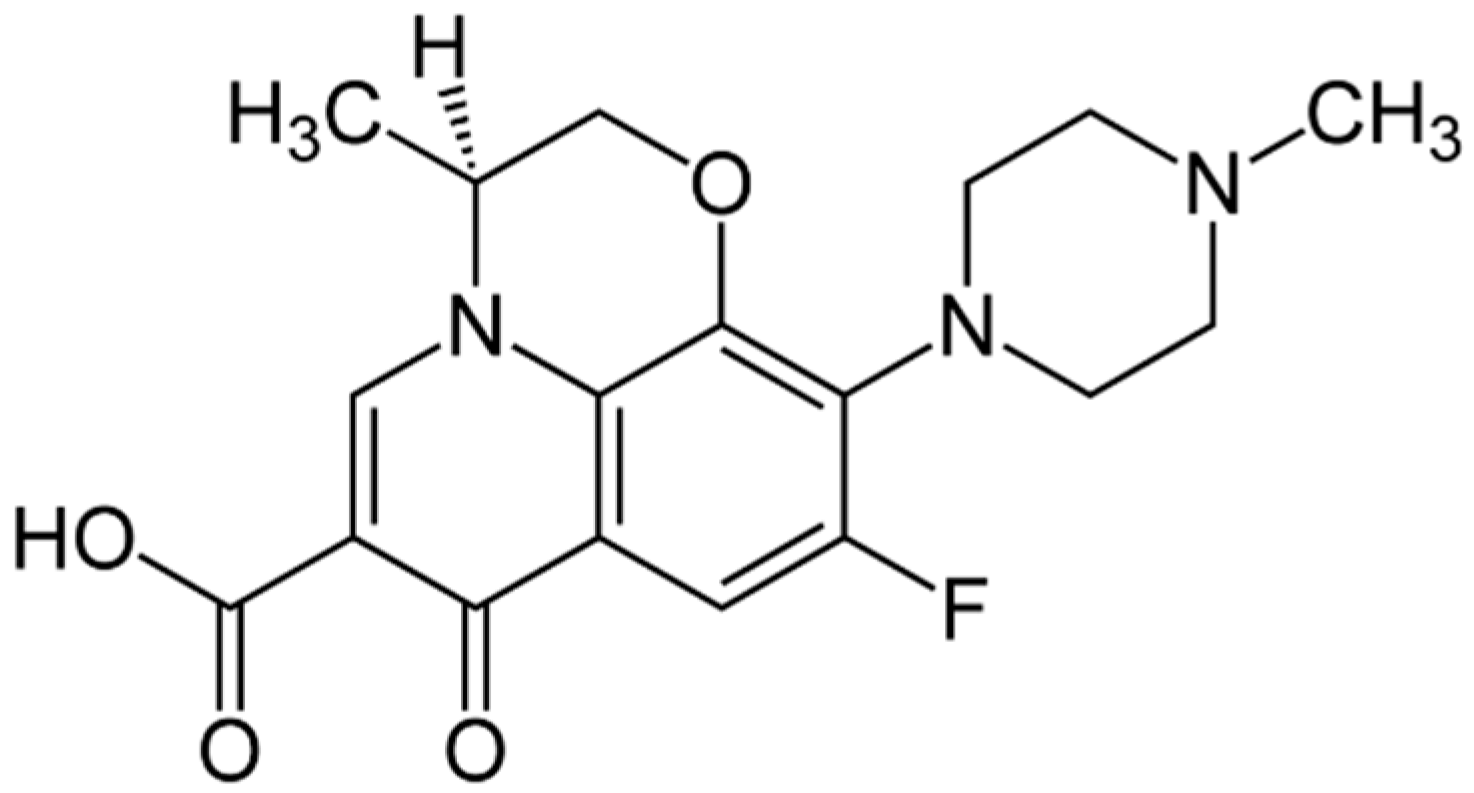

Highly Sensitive Electrochemical Detection of Levofloxacin Using a Mn (III)-Porphyrin Modified ITO Electrode

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. Apparatus

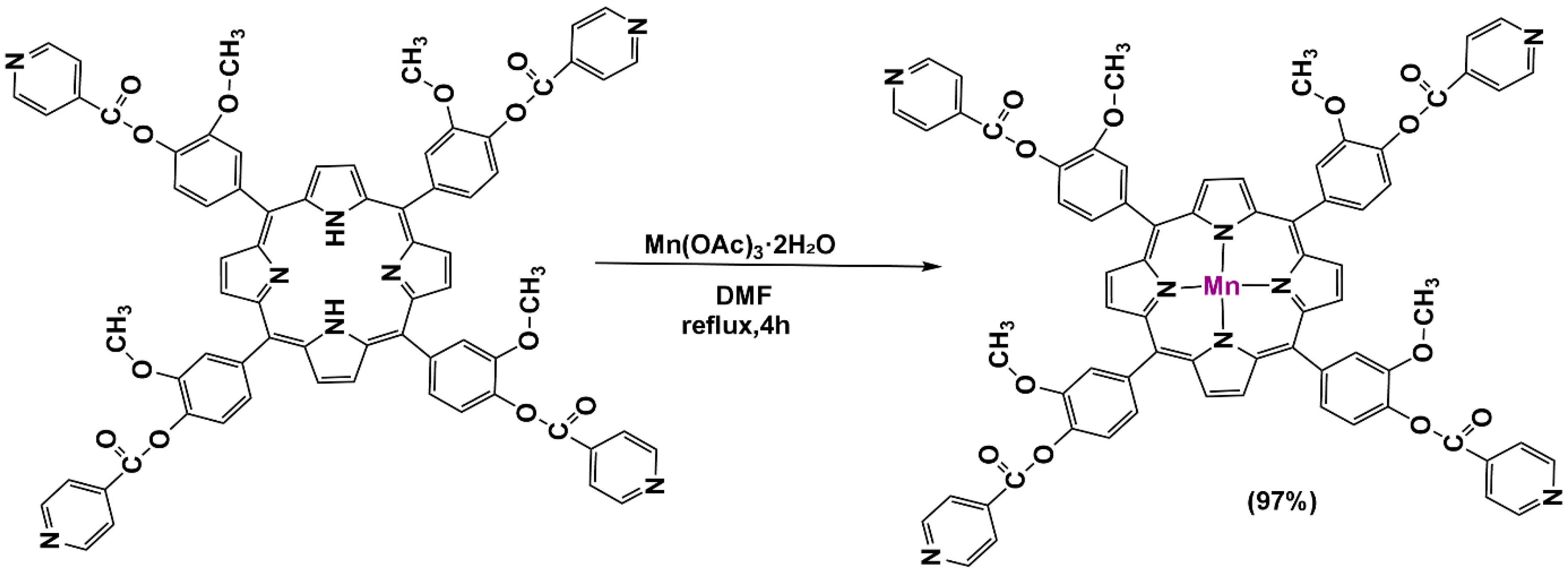

2.3. Synthesis of [5,10,15,20-Tetrayltetrakis(2-methoxybenzene-4,1-diyl) Tetraisonicotinateporphyrinato] Manganese (III): [MnTMIPP]

2.4. Preparation of MnTMIPP/ITO Electrode

3. Results and Discussion

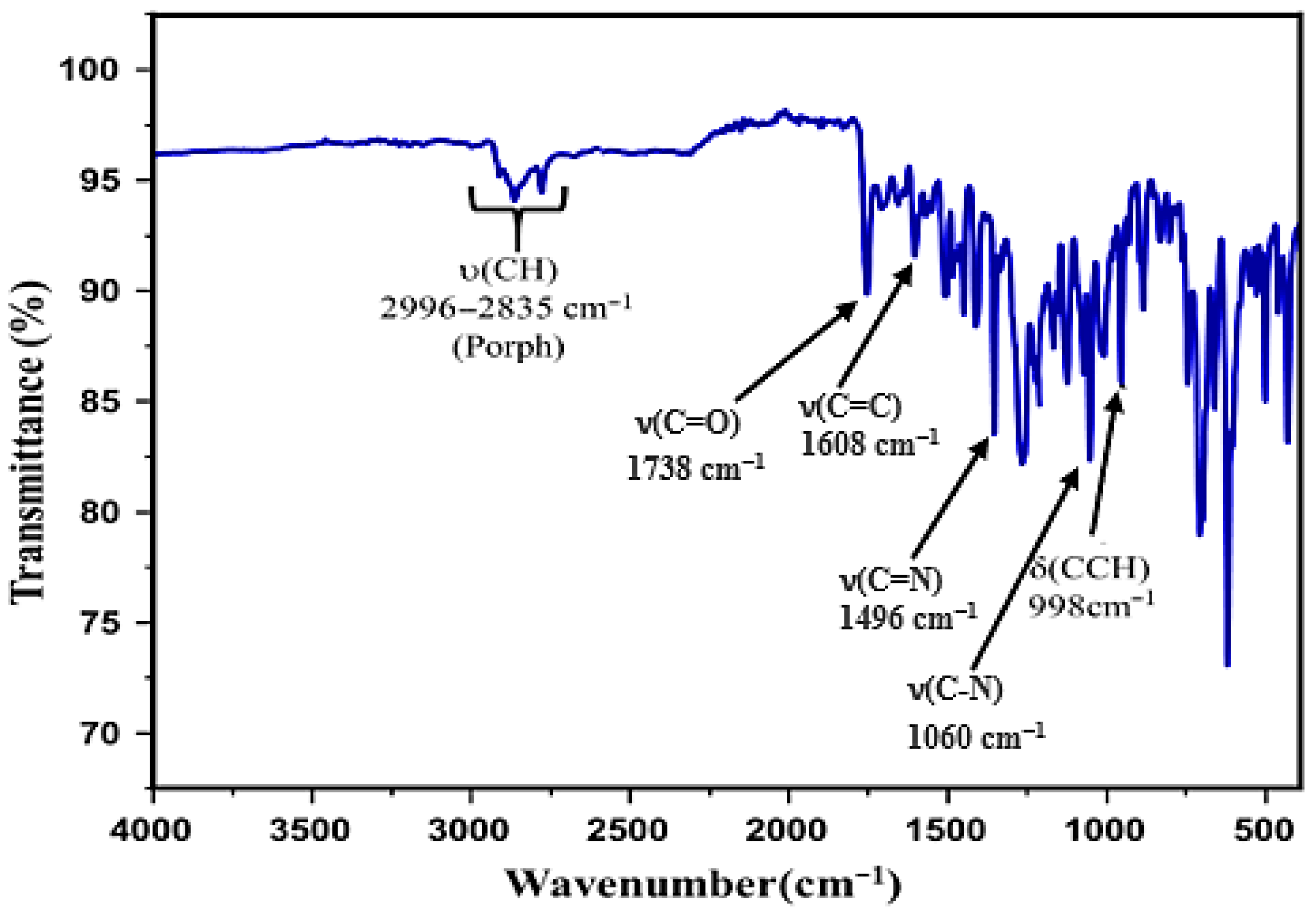

3.1. Characterization of MnTMIPP

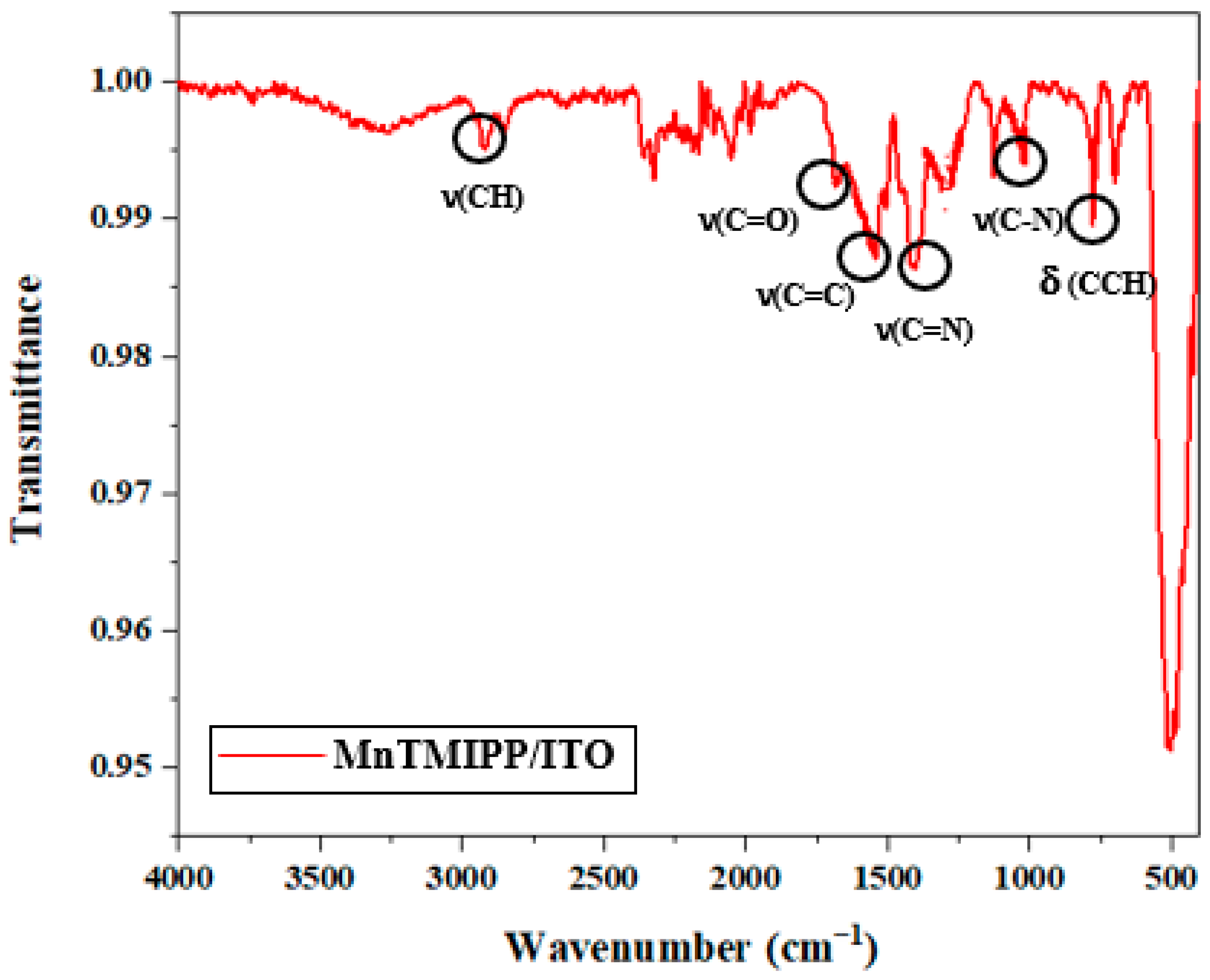

3.1.1. IR Spectroscopies

3.1.2. UV/Vis Spectrometry

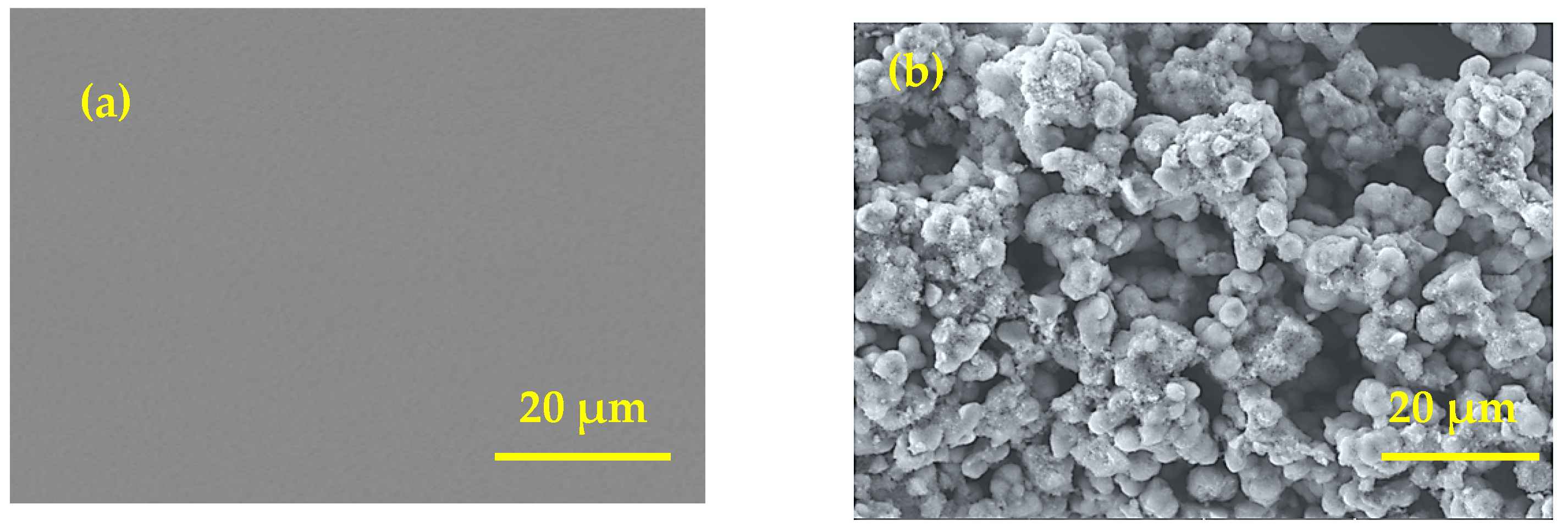

3.2. Morphological and Structural Characterization of MnTMIPP/ITO Electrode

- UV–Vis Spectroscopy: The spectrum exhibited the characteristic, sharp Soret and Q bands with the expected profile for a manganese (III) porphyrin. The absence of extraneous peaks indicates no significant organic impurities or demetallation.

- FTIR Spectroscopy: The spectrum confirmed the presence of all key functional groups from the porphyrin ligand. Crucially, it showed the absence of vibrational bands diagnostic of common impurities or unreacted starting materials.

- Energy-Dispersive X-ray (EDX) Spectroscopy: This analysis provided direct elemental evidence, confirming the presence of Mn, N, C, and O. The obtained wt% of Mn, N, C, O were consistent with the expected stoichiometry, ruling out major inorganic contaminants or free Mn ions.

3.3. Electrochemical Behavior of MnTMIPP Membrane in the Presence of Levofloxacin

3.4. Optimization of Experimental Conditions

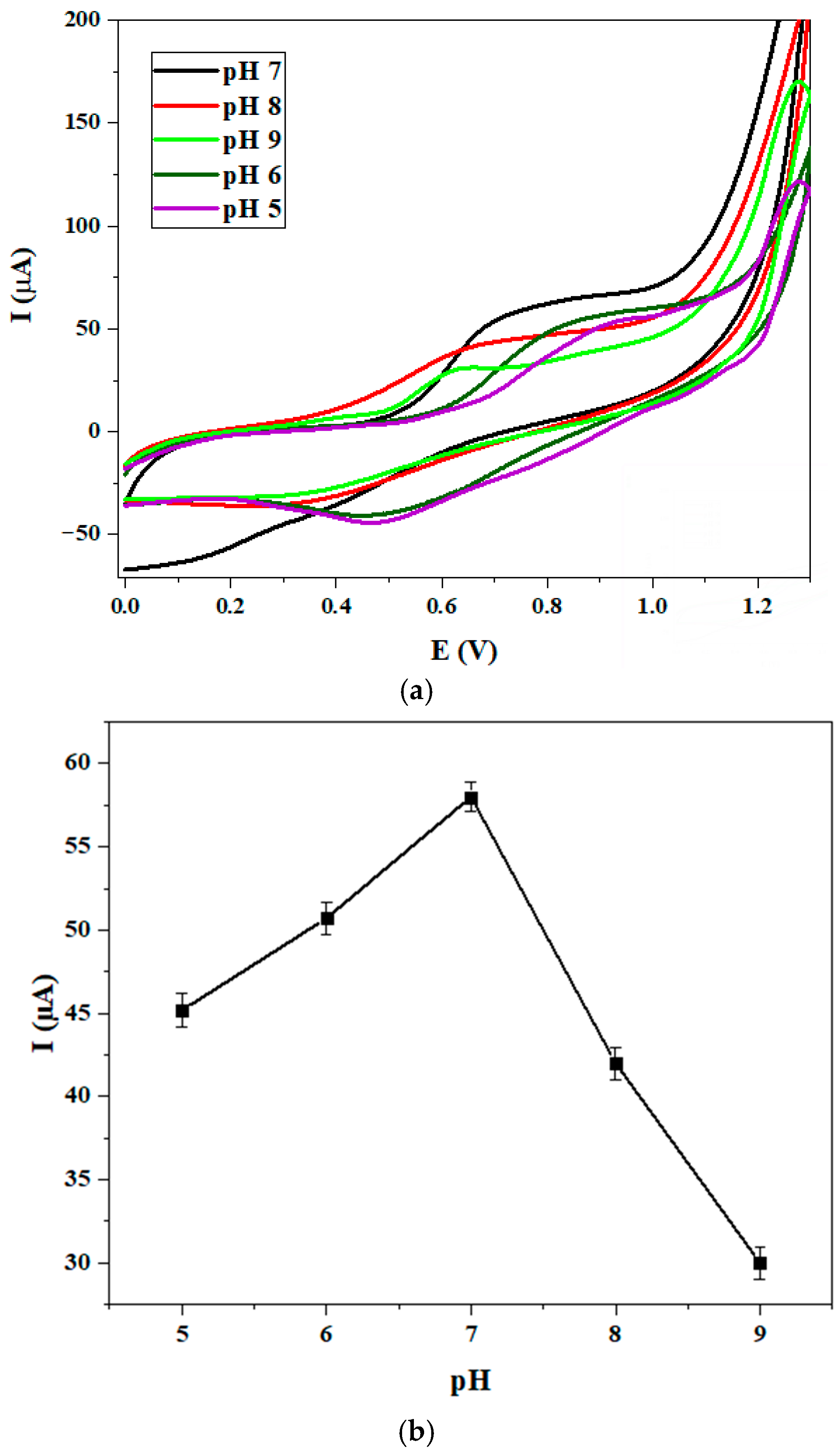

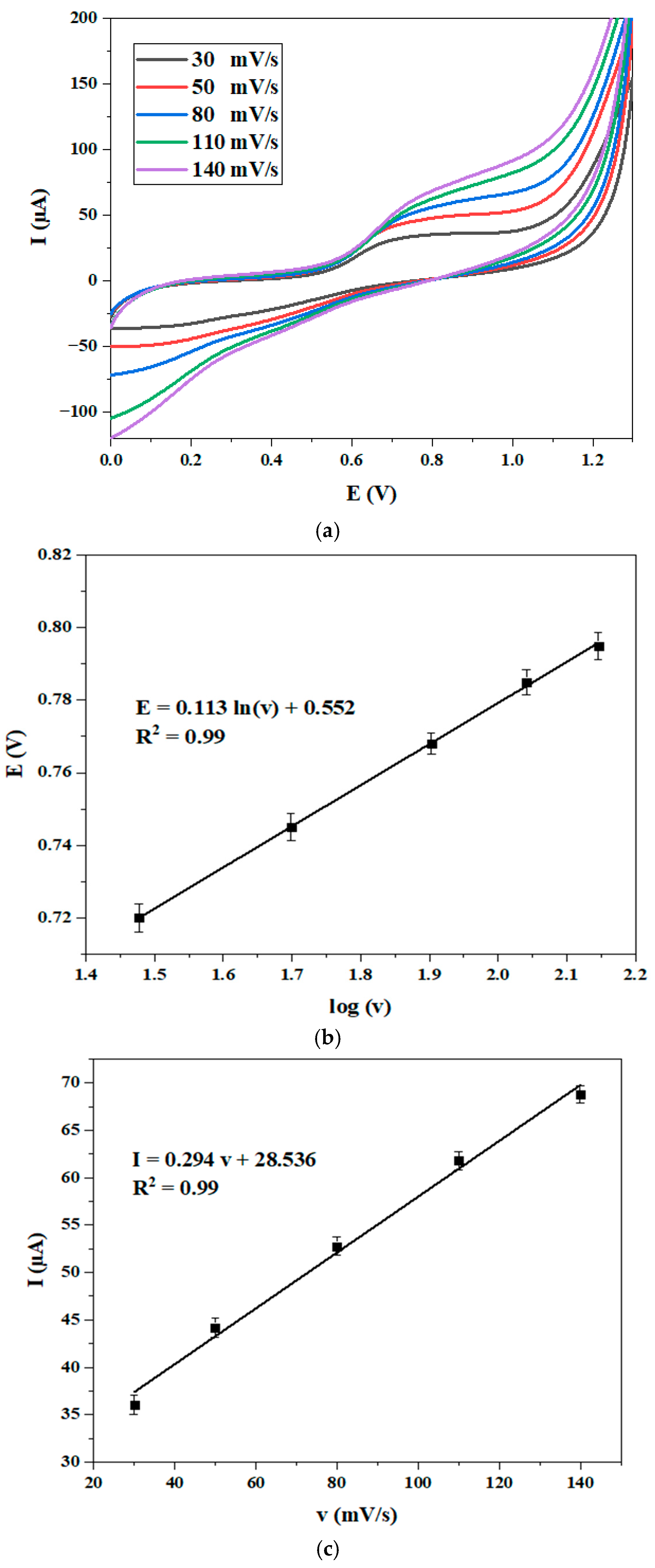

3.4.1. pH Effect

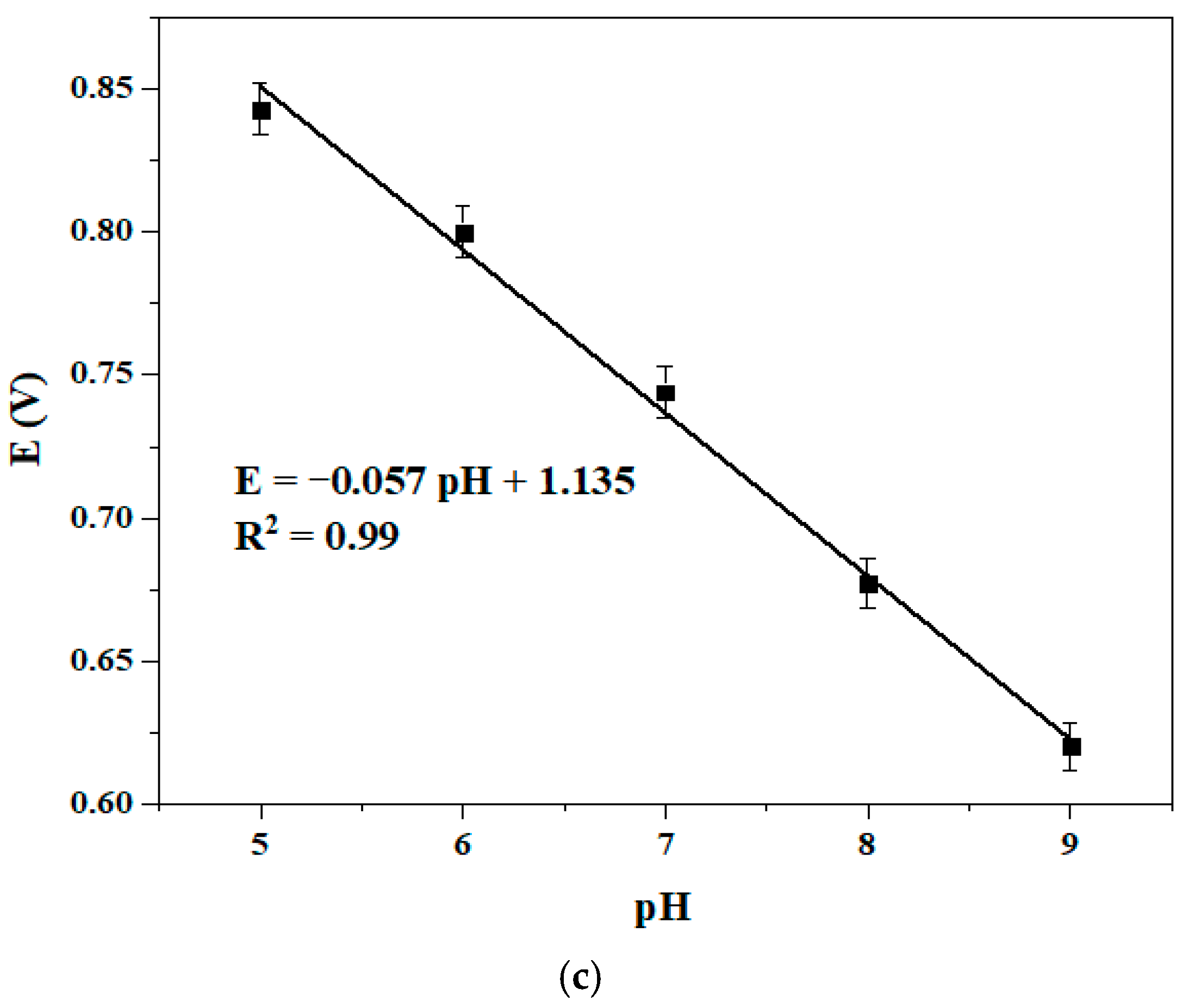

3.4.2. Effect of Scan Rate

3.5. Analytical Performance of the Proposed Sensor

3.5.1. Determination of LEV

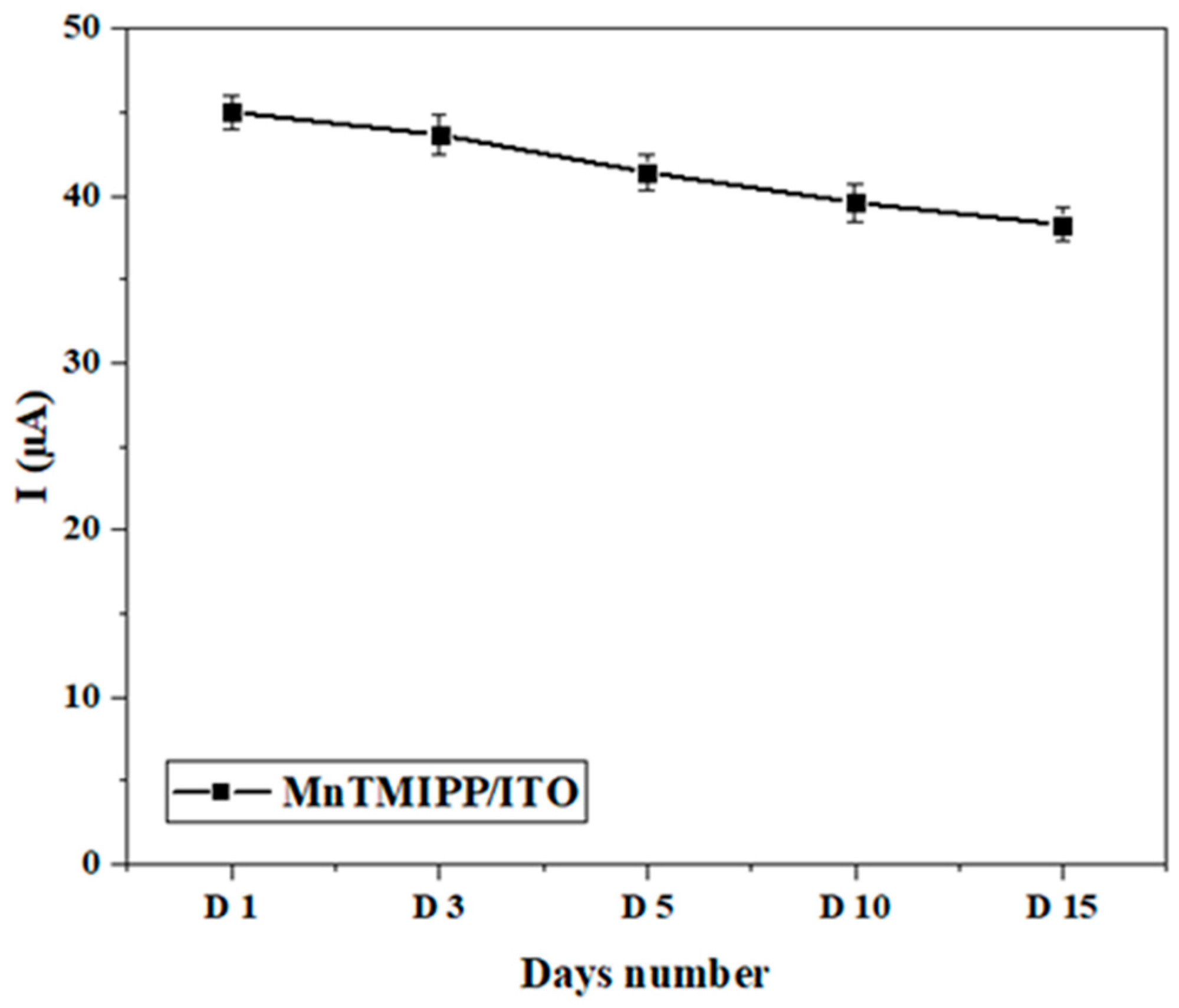

3.5.2. Reproducibility, Repeatability, and Stability

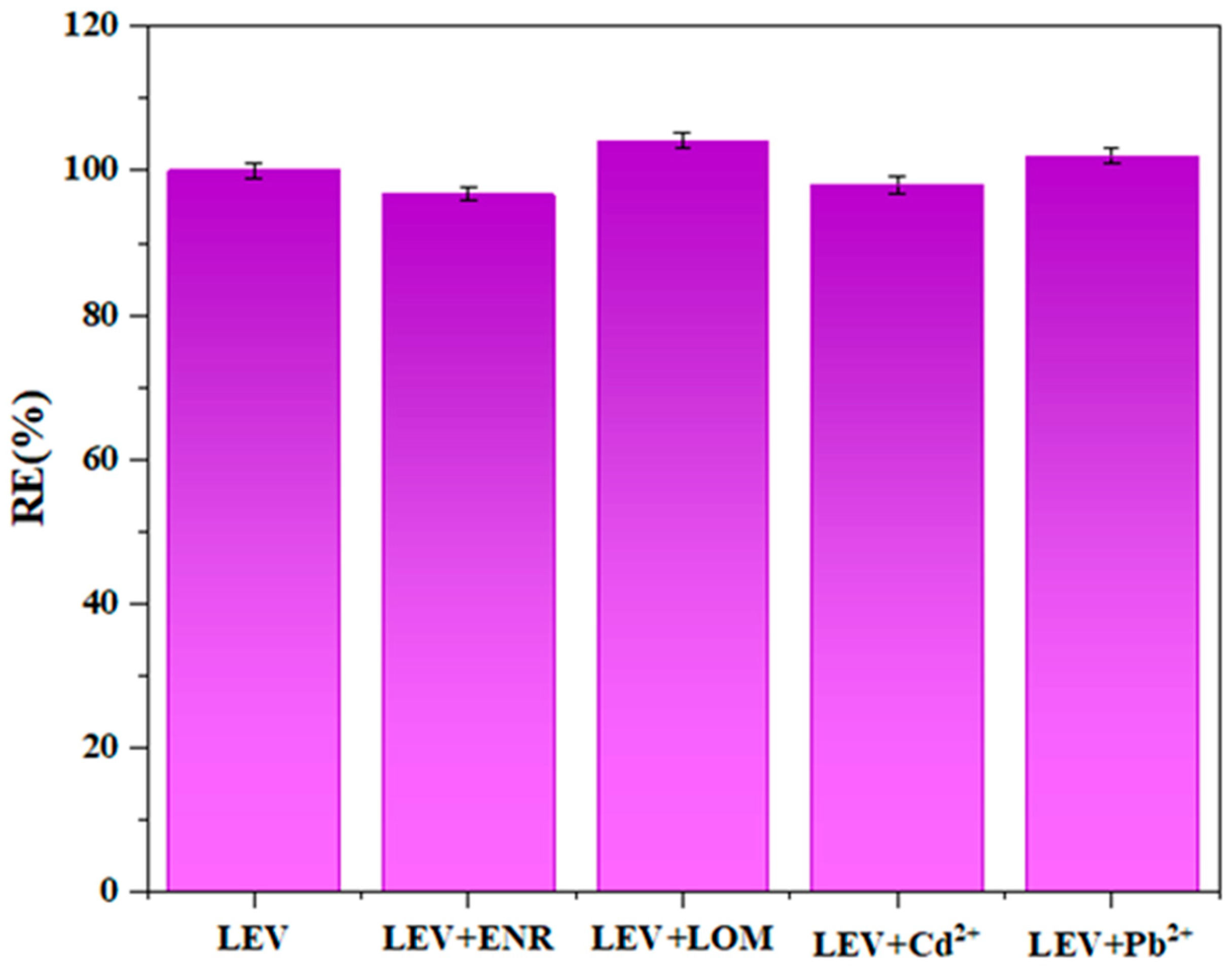

3.5.3. Selectivity

3.6. Real Sample Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Petitjeans, F.; Nadaud, J.; Perez, J.P.; Debien, B.; Olive, F.; Villevieille, T.; Pats, B. A Case of Rhabdomyolysis with Fatal Outcome after a Treatment with Levofloxacin. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2003, 59, 779–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyanova, L.; Ilieva, J.; Gergova, G.; Mitov, I. Levofloxacin Susceptibility Testing against Helicobacter Pylori: Evaluation of a Modified Disk Diffusion Method Compared to E Test. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 84, 55–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venuta, F.; Rendina, E.A. Combined Pulmonary Artery and Bronchial Sleeve Resection. Oper. Tech. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2008, 13, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famularo, G.; Pizzicannella, M.; Gasbarrone, L. Levofloxacin and Seizures: What Risk for Elderly Adults? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, N.; Manocha, D.; Madhira, B. Life-Threatening Metabolic Coma Caused by Levofloxacin. Am. J. Ther. 2015, 22, e48–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.M.; Cao, J.T.; Tian, W.; Zheng, Y.L. Determination of Levofloxacin and Norfloxacin by Capillary Electrophoresis with Electrochemiluminescence Detection and Applications in Human Urine. Electrophoresis 2008, 29, 3207–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumka, V.K. Disposition Kinetics and Dosage Regimen of Levofloxacin on Concomitant Administration with Paracetamol in Crossbred Calves. J. Vet. Sci. 2007, 8, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando, M.D.; Mezcua, M.; Fernández-Alba, A.R.; Barceló, D. Environmental Risk Assessment of Pharmaceutical Residues in Wastewater Effluents, Surface Waters and Sediments. Talanta 2006, 69, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szerkus, O.; Jacyna, J.; Wiczling, P.; Gibas, A.; Sieczkowski, M.; Siluk, D.; Matuszewski, M.; Kaliszan, R.; Markuszewski, M.J. Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatographic Determination of Levofloxacin in Human Plasma and Prostate Tissue with Use of Experimental Design Optimization Procedures. J. Chromatogr. B 2016, 1029–1030, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, Z.Q.; Lui, G.; Hirt, D.; Treluyer, J.M.; Benaboud, S.; Aboura, R.; Gana, I. Simultaneous quantification of levofloxacin, pefloxacin, ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin in microvolumes of human plasma using high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2019, 33, e4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.J.; He, J.M.; Zhang, R.P.; Wang, Y.C.; Wang, J.X.; Wang, H.Q.; Wu, Y.; He, W.Y.; Abliz, Z. An integrated approach for detection and characterization of the trace impurities in levofloxacin using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Publ. Mass Spectrom. 2014, 28, 1164–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, Y.H.; Bair, M.J.; Hu, C.C. Determination of Levofloxacin in Human Urine with Capillary Electrophoresis and Fluorescence Detector. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2007, 54, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Y.; Bao, T.; Hu, T.X.; Wen, W.; Zhang, X.H.; Wang, S.F. Voltammetric Determination of Levofloxacin Using a Glassy Carbon Electrode Modified with Poly(o-Aminophenol) and Graphene Quantum Dots. Microchim. Acta 2017, 184, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Santos, A.M.; Fatibello-Filho, O. Simultaneous Determination of Paracetamol and Levofloxacin Using a Glassy Carbon Electrode Modified with Carbon Black, Silver Nanoparticles and PEDOT:PSS Film. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 255, 2264–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, J. Electrochemical Sensor for Levofloxacin Based on Molecularly Imprinted Polypyrrole–Graphene–Gold Nanoparticles Modified Electrode. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 192, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Tong, Y.; Zheng, R.; Liu, W.; Gu, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Z. Ag Nanoparticles and Electrospun CeO2-Au Composite Nanofibers Modified Glassy Carbon Electrode for Determination of Levofloxacin. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 203, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Li, J. Determination of Levofloxacin Hydrochloride with Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes-Polymeric Alizarin Film Modified Electrode. Russ. J. Electrochem. 2010, 46, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radi, A.; El-Sherif, Z. Determination of Levofloxacin in Human Urine by Adsorptive Square-Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry on a Glassy Carbon Electrode. Talanta 2002, 58, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Abdiryim, T.; Jamal, R.; Liu, X.; Xue, C.; Xie, S.; Tang, X.; Wei, J. A Novel Molecularly Imprinted Electrochemical Sensor from Poly (3, 4-Ethylenedioxythiophene)/Chitosan for Selective and Sensitive Detection of Levofloxacin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 267, 131321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Xu, G.; Li, X.; Ma, J.; Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, D.; Li, D. Fast Cathodic Reduction Electrodeposition of a Binder-Free Cobalt-Doped Ni-MOF Film for Directly Sensing of Levofloxacin. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 851, 156823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi Nguyen, Q.X.; Dang, T.D.; Cao, H.H.; La, D.D. Self-Assembled Porphyrin on Fe/Graphene: A Versatile Electrode for Nitrofurantoin Antibiotic Sensing. Microchem. J. 2025, 212, 113418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Jiang, J.; Guo, Z.; Zhao, S.; Song, J.; Lu, G.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Q. Nonenzymatic Flexible Electrochemical Sensor For Levofloxacin Detecting Based on Bimetallic Sulfide Modified Porphyrin Composites. SSRN 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Shang, H.; Liu, X.; Lu, X. Comparative Electrochemical Behaviors of a Series of SH-Terminated- Functionalized Porphyrins Assembled on a Gold Electrode by Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy (SECM). J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 10436–10441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsine, Z.; Bizid, S.; Zahou, I.; Ben Haj Hassen, L.; Nasri, H.; Mlika, R. A Highly Sensitive Impedimetric Sensor Based on Iron (III) Porphyrin and Thermally Reduced Graphene Oxide for Detection of Bisphenol A. Synth. Met. 2018, 244, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, S.; Labuta, J.; Van Rossom, W.; Ishikawa, D.; Minami, K.; Hill, J.P.; Ariga, K. Porphyrin-Based Sensor Nanoarchitectonics in Diverse Physical Detection Modes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 9713–9746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Lin, Z.; Liu, F.; Kong, F.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, Q.; Zou, B. Research Progress on the Application of Metal Porphyrin Electrochemical Sensors in the Detection of Phenolic Antioxidants in Food. Polymers 2025, 17, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolesse, R.; Nardis, S.; Monti, D.; Stefanelli, M.; Di Natale, C. Porphyrinoids for Chemical Sensor Applications. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 2517–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc La, D.; Khong, H.M.; Nguyen, X.Q.; Dang, T.D.; Bui, X.T.; Nguyen, M.K.; Ngo, H.H.; Nguyen, D.D. A Review on Advances in Graphene and Porphyrin-Based Electrochemical Sensors for Pollutant Detection. Sustain. Chem. One World 2024, 3, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Offenhäusser, A.; Ermolenko, Y.; Mourzina, Y. Biomimetic Sensor Based on Mn(III) Meso-Tetra(N-Methyl-4-Pyridyl) Porphyrin for Non-Enzymatic Electrocatalytic Determination of Hydrogen Peroxide and as an Electrochemical Transducer in Oxidase Biosensor for Analysis of Biological Media. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 321, 128437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, A.; Yu, K.; Asinyo, B.K.; Chai, H.; Raza, T.; Xu, T.; Zhang, G.; Qu, L. A Portable Electrochemical Sensor Based on Manganese Porphyrin-Functionalized Carbon Cloth for Highly Sensitive Detection of Nitroaromatics and Gaseous Phenol. Langmuir 2022, 38, 12058–12069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adleb, A.D.; Longo, F.R.; Finarelli, J.D.; Goldmacher, J.; Assour, J.; Korsakoff, L. A Simplified Synthesis for Meso-Tetraphenylporphine. J. Org. Chem. 1967, 32, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkacher, H.; Ben Taheur, F.; Amiri, N.; Almahri, A.; Loiseau, F.; Molton, F.; Vollbert, E.M.; Roisnel, T.; Turowska-Tyrk, I.; Nasri, H. DMAP and HMTA Manganese(III) Meso-Tetraphenylporphyrin-Based Coordination Complexes: Syntheses, Physicochemical Properties, Structural and Biological Activities. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2023, 545, 121278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardouri, N.E.; Hrichi, S.; Torres, P.; Chaâbane-Banaoues, R.; Sorrenti, A.; Roisnel, T.; Turowska-Tyrk, I.; Babba, H.; Crusats, J.; Moyano, A.; et al. Synthesis, Characterization, X-Ray Molecular Structure, Antioxidant, Antifungal, and Allelopathic Activity of a New Isonicotinate-Derived Meso-Tetraarylporphyrin. Molecules 2024, 29, 3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, L.J. Manganese Porphyrin Complexes. III. Spectroscopy of Chloroaquo Complexes of Several Porphyrins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 2725–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, M.A.; Szabó, P.; Lendvay, G.; Horváth, O. Characterization of the UV-Visible Absorption Spectra of Manganese(III) Porphyrins with Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory Calculations. Z. Für Phys. Chem. 2022, 236, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harhouri, W.; Dhifaoui, S.; Denden, Z.; Roisnel, T.; Blanchard, F.; Nasri, H. Synthesis, Spectroscopic Characterizations, Cyclic Voltammetry Investigation and Molecular Structure of the High-Spin Manganese(III) Trichloroacetato Meso-Tetraphenylporphyrin and Meso-Tetra-(Para-Bromophenyl)Porphyrin Complexes. Polyhedron 2017, 130, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harhouri, W.; McHiri, C.; Najmudin, S.; Bonifácio, C.; Nasri, H. Synthesis, FT-IR Characterization and Crystal Structure of Aqua(5,10,15,20-Tetraphenylporphyrinato-Κ4 N)Manganese(III) Trifluoromethanesulfonate. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Crystallogr. Commun. 2016, 72, 720–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaughan, R.R.; Shriver, D.F.; Boucher, L.J. Resonance Raman Spectra of Manganese (III) Tetraphenylporphin Halides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1975, 72, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.L.; Hollander, F.J. Structural Characterization of a Complex of Manganese(V): Nitrido[Tetrakis(p-Methoxyphenyl)Porphinato]-Manganese(V). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 7318–7319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkacher, H.; Gassoumi, B.; Dardouri, N.E.; Nasri, S.; Loiseau, F.; Molton, F.; Roisnel, T.; Turowska-Tyrk, I.; Ghala, H.; Acherar, S.; et al. Photophysical, Cyclic Voltammetry, Electron Paramagnetic Resonance, X-Ray Molecular Structure, DFT Calculations and Molecular Docking Study of a New Mn(III) Metalloporphyrin. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1319, 139455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejab, F.; Dardouri, N.E.; Rouis, A.; Echabaane, M.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N.; Ben Halima, H. Highly Sensitive Electrochemical Sensor Based on Zn Porphyrin for Environmental Monitoring of Glyphosate. Electroanalysis 2025, 37, e70037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, S.; Karuppasamy, K.; Msolli, S.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, J.-H. A nanocrystalline structured NiO/MnO2@nitrogendoped graphene oxide hybrid nanocomposite for high performance supercapacitors. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 15517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, D.; Nardis, S.; Stefanelli, M.; Paolesse, R.; Di Natale, C.; D’Amico, A. Porphyrin-Based Nanostructures for Sensing Applications. Sensors 2009, 2009, 856053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebdelli, R.; Rouis, A.; Mlika, R.; Bonnamour, I.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N.; Ben Ouada, H.; Davenas, J. Electrochemical Impedance Detection of Hg2+, Ni2+ and Eu3+ Ions by a New Azo-Calix[4]Arene Membrane. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2011, 661, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagumalai, K.; Palanisamy, S.; Kumar, P.S.; ElNaker, N.A.; Kim, S.C.; Chiesa, M.; Prakash, P. Improved Electrochemical Detection of Levofloxacin in Diverse Aquatic Samples Using 3D Flower-like Co@CaPO4 Nanospheres. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 343, 123189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejab, F.; Dardouri, N.E.; Rouis, A.; Echabaane, M.; Nasri, H.; Lakard, B.; Ben Halima, H.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N. A Selective Electrochemical Sensor for Bisphenol A Detection Based on Cadmium (II) (Bromophenyl)Porphyrin and Gold Nanoparticles. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejab, F.; Rouis, A.; Echabaane, M.; Ben Khelifa, A.; Ezzayani, K. A Novel Electrochemical Sensor for the Detection of Endocrine Disruptor Bisphenol A Based on Magnesium (II) Porphyrin. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejab, F.; Dardouri, N.E.; Rouis, A.; Echabaane, M.; Nasri, H.; Ben Halima, H.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N. A Novel Electrochemical Platform Based on Cadmium (II) (Fluorophenyl)Porphyrin and Gold Nanoparticles Modified Screen-Printed Electrode Electrode for the Sensitive Detection of Bisphenol A. Electroanalysis 2025, 37, e12017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejab, F.; Echabaane, M.; Rouis, A.; Ben Ouada, H. A Novel Impedimetric Platform Based on Extracellular Polymeric Substances Production in Spirulina (Arthrospira sp.) Functionalized Platinum Electrode for Detection of Copper. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekry, A.M. An Innovative Simple Electrochemical Levofloxacin Sensor Assembled from Carbon Paste Enhanced with Nano-Sized Fumed Silica. Biosensors 2022, 12, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Azab, N.F.; Mahmoud, A.M.; Trabik, Y.A. Point-of-Care Diagnostics for Therapeutic Monitoring of Levofloxacin in Human Plasma Utilizing Electrochemical Sensor Mussel-Inspired Molecularly Imprinted Copolymer. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 918, 116504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhimaraya, K.; Manjunatha, J.G.; Moulya, K.P.; Tighezza, A.M.; Albaqami, M.D.; Sillanpää, M. Detection of Levofloxacin Using a Simple and Green Electrochemically Polymerized Glycine Layered Carbon Paste Electrode. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Kasturi, P.R.; Breslin, C.B. Ultra-Sensitive Electrochemical Detection of Levofloxacin Using a Binder-Free Copper and Graphene Composite. Talanta 2024, 275, 126132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Gu, H.; Wei, D.; Xu, Y.C.; Fu, W.; Yu, Z. Conformational Preferences of π-π Stacking Between Ligand and Protein, Analysis Derived from Crystal Structure Data Geometric Preference of π-π Interaction. Interdiscip. Sci. 2015, 7, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lage, A.L.A.; Marciano, A.C.; Venâncio, M.F.; da Silva, M.A.N.; Martins, D.C.d.S. Water-Soluble Manganese Porphyrins as Good Catalysts for Cipro- and Levofloxacin Degradation: Solvent Effect, Degradation Products and DFT Insights. Chemosphere 2021, 268, 129334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Complex | Solvent | Soret Bands | Q Bands | Eg-Opt (eV) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λmax (nm) (logε) | |||||

| [MnIII(TBrPP)(TCA)] a.b | CH2Cl2 380, 403 | 474 | 575, 610 | [36] | |

| [MnIII(TPP)(H2O)](SO3CF3) c | CHCl3 386 | 474 | 570, 604 | [37] | |

| [MnIII(TPP)Cl] c | CHCl3 376 | 476 | 581, 617, 690 | [38] | |

| [MnIII(TPP)(NO2)] c | Benzene 380. 400 | 476 | 583, 620 | [39] | |

| [MnIII(TMPP)(OAc)] d | CH2Cl2 382(5.98), 407(5.96), 482 (6.08) 586(5.42), 624(5.44) | 1.912 | [32] | ||

| [MnIII(TMPP)(SO3CF3)] d | CH2Cl2 394(6.09), 410(6.06), 481 (6.08) 577(5.53), 614(5.56) | 1.931 | [32] | ||

| [MnIII(TClPP)(OAc)] e | CH2Cl2 382(5.33), 402(5.29), 479 (5.53) 583(4.87), 621(4.91) | 1.931 | [40] | ||

| [MnIII(TMIPP)(OAc)] | CH2Cl2 381(5.33), 403(5.29), 478 (5.53) 581(4.87), 623(4.91) | 1.934 | This work | ||

| Samples | ITO | MnTMIPP/ITO |

|---|---|---|

|  | |

| WCA (°) | 56 ± 1 | 75 ± 0.7 |

| Electrode | Technique | Range | Limit of Detection | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCE/Polyaminophenl/GrQD | LSV | 0.05–100 µM | 10 nM | [13] |

| GCE/C black/AgNPs/PEDOT/PSS | SWV | 0.67–12 µM | 12 nM | [14] |

| GCE/(PPy/Gr/AuNPs)MIP | DPV | 1–100 µM | 0.53 µM | [15] |

| GCE/AgNPs/electrospun CeO-Au composite | DPV | 0.03–10 µM | 0.01 µM | [16] |

| GCE/MWCNT/polm Alizarin film/ | LSV | 5.0–100 µM | 0.40 µM | [17] |

| GCE | AdSWV | 6 nM–0.5 µM | 5 nM | [18] |

| GCE/(PolyEthdioxythiophene/chitosan)MIP | DPV | 1.9 nM–1000 µM | 0.4 nM | [19] |

| NFS/CPE | DPV | 0.2–1000 µM | 0.09 µM | [50] |

| PGE/Au-NPs/polyoPD-co-l-Dopa | SWV | 1–100 μM | 0.462 µM | [51] |

| EPGNL/CPE | DPV | 30–90 µM | 0.8436 µM | [52] |

| GCE/Gr/Cu | CV | 30–90 nM | 11.86 nM | [53] |

| GCE/Co@CaHPO | DPV | 0.3–460 μM | 0.151 μM | [45] |

| MnTMIPP/ITO | CV | 1 nM–103 µM | 0.482 nM | This work |

| Added (M) | Found (M) | Recovery (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saliva | 10−4 | 1.037 × 10−4 | 103.7 ± 3.6 |

| 10−7 | 1.048 × 10−7 | 104.8 ± 3.7 | |

| River water | 10−4 | 1.051 × 10−4 | 105.1 ± 3.7 |

| 10−7 | 1.06 × 10−7 | 106.0 ± 3.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rejab, F.; Dardouri, N.E.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N.; Ben Halima, H. Highly Sensitive Electrochemical Detection of Levofloxacin Using a Mn (III)-Porphyrin Modified ITO Electrode. Chemosensors 2026, 14, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010002

Rejab F, Dardouri NE, Jaffrezic-Renault N, Ben Halima H. Highly Sensitive Electrochemical Detection of Levofloxacin Using a Mn (III)-Porphyrin Modified ITO Electrode. Chemosensors. 2026; 14(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleRejab, Fatma, Nour Elhouda Dardouri, Nicole Jaffrezic-Renault, and Hamdi Ben Halima. 2026. "Highly Sensitive Electrochemical Detection of Levofloxacin Using a Mn (III)-Porphyrin Modified ITO Electrode" Chemosensors 14, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010002

APA StyleRejab, F., Dardouri, N. E., Jaffrezic-Renault, N., & Ben Halima, H. (2026). Highly Sensitive Electrochemical Detection of Levofloxacin Using a Mn (III)-Porphyrin Modified ITO Electrode. Chemosensors, 14(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010002