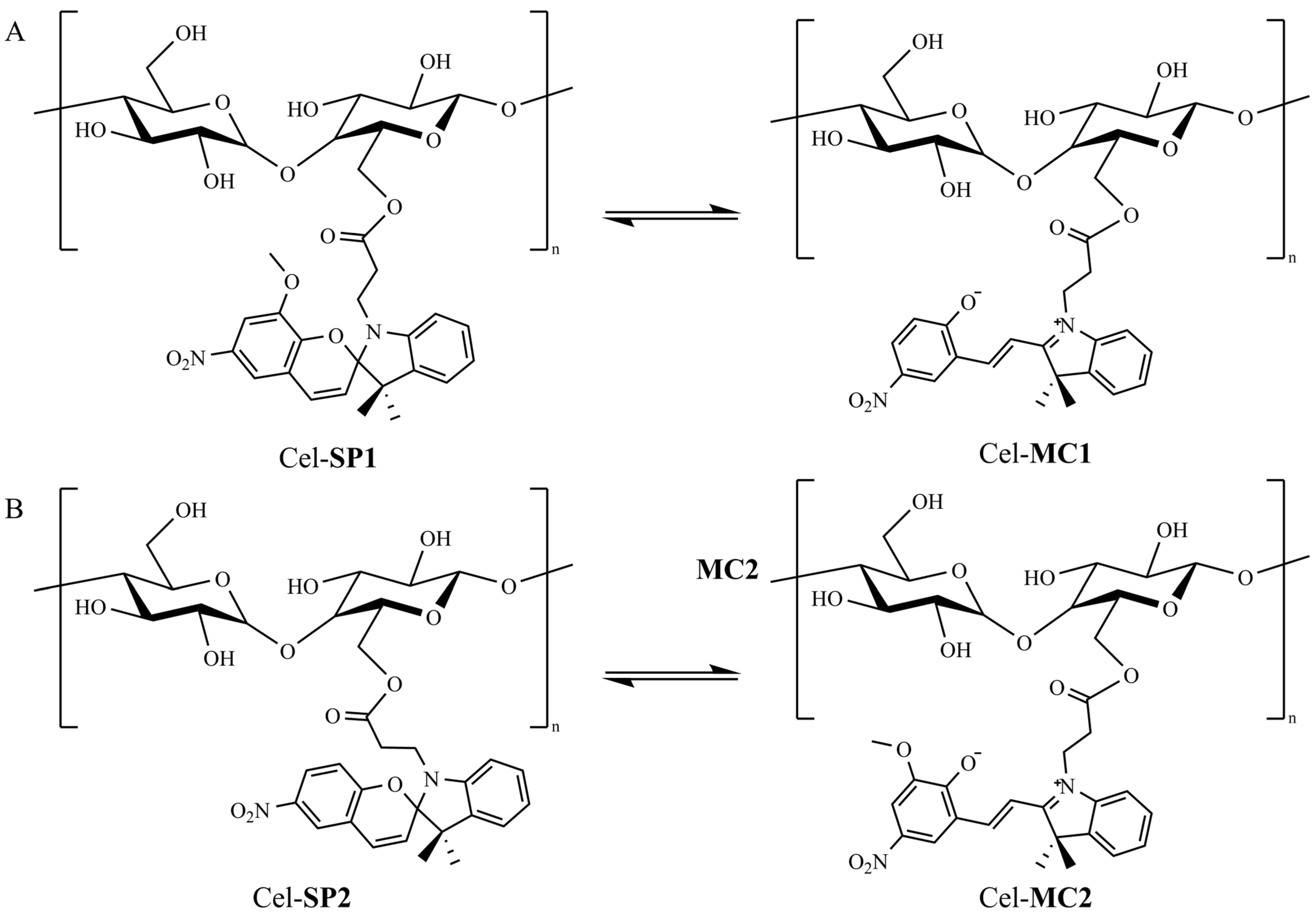

Spiropyran-Modified Cellulose for Dual Solvent and Acid/Base Vapor Sensing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Solvents

2.2. Esterification of Cellulose

2.3. Solid-State Characterization

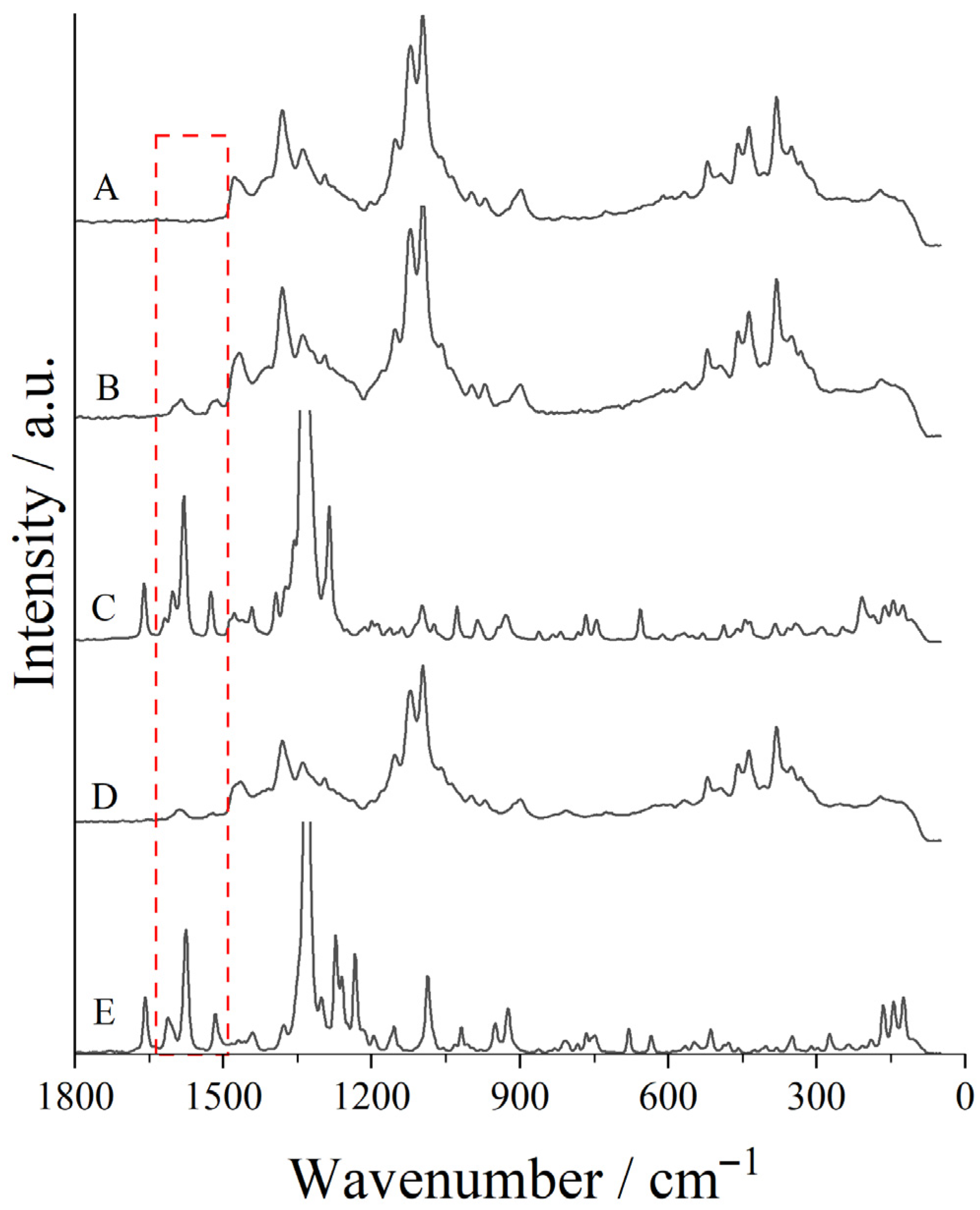

2.3.1. Raman Spectroscopy

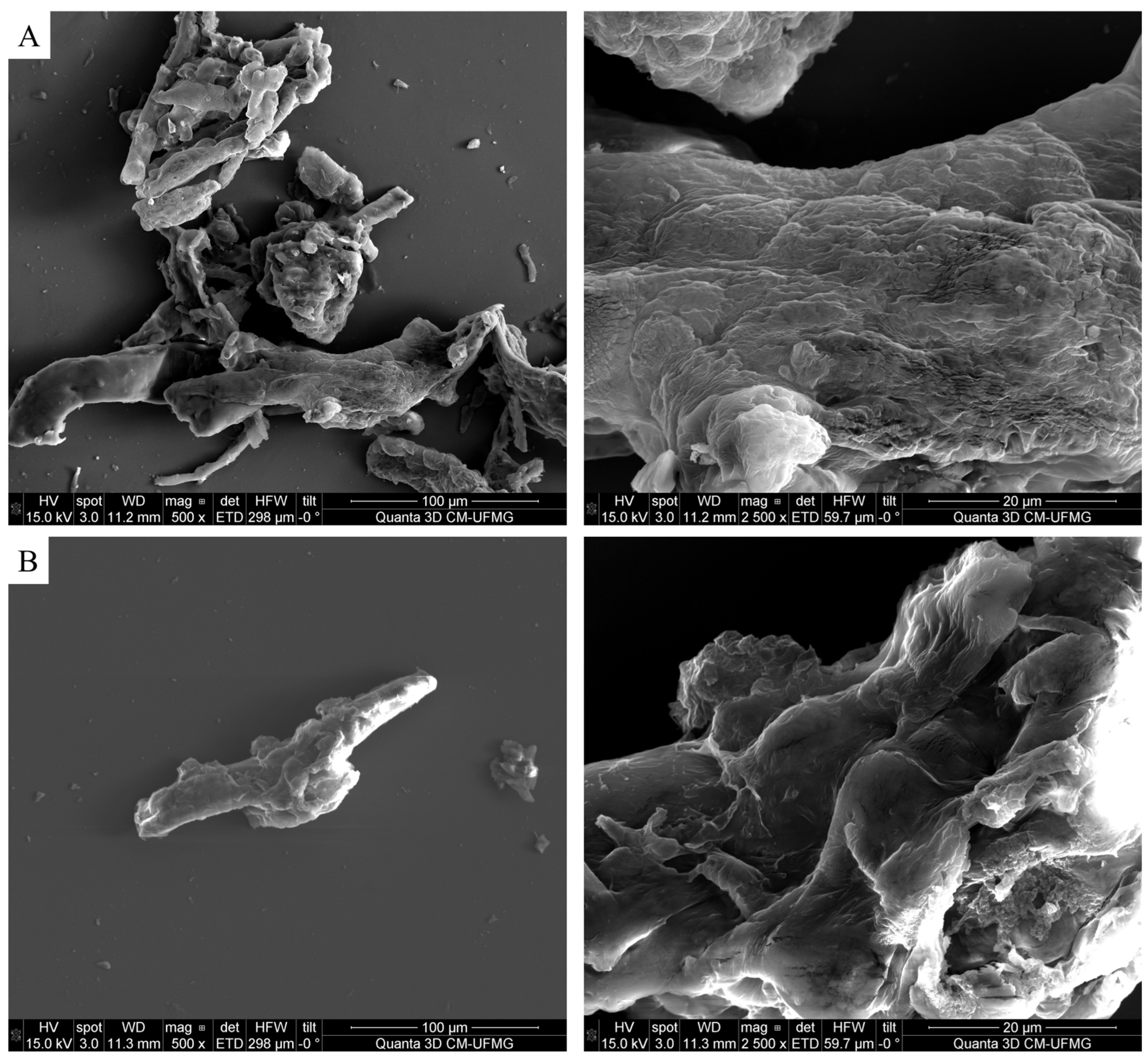

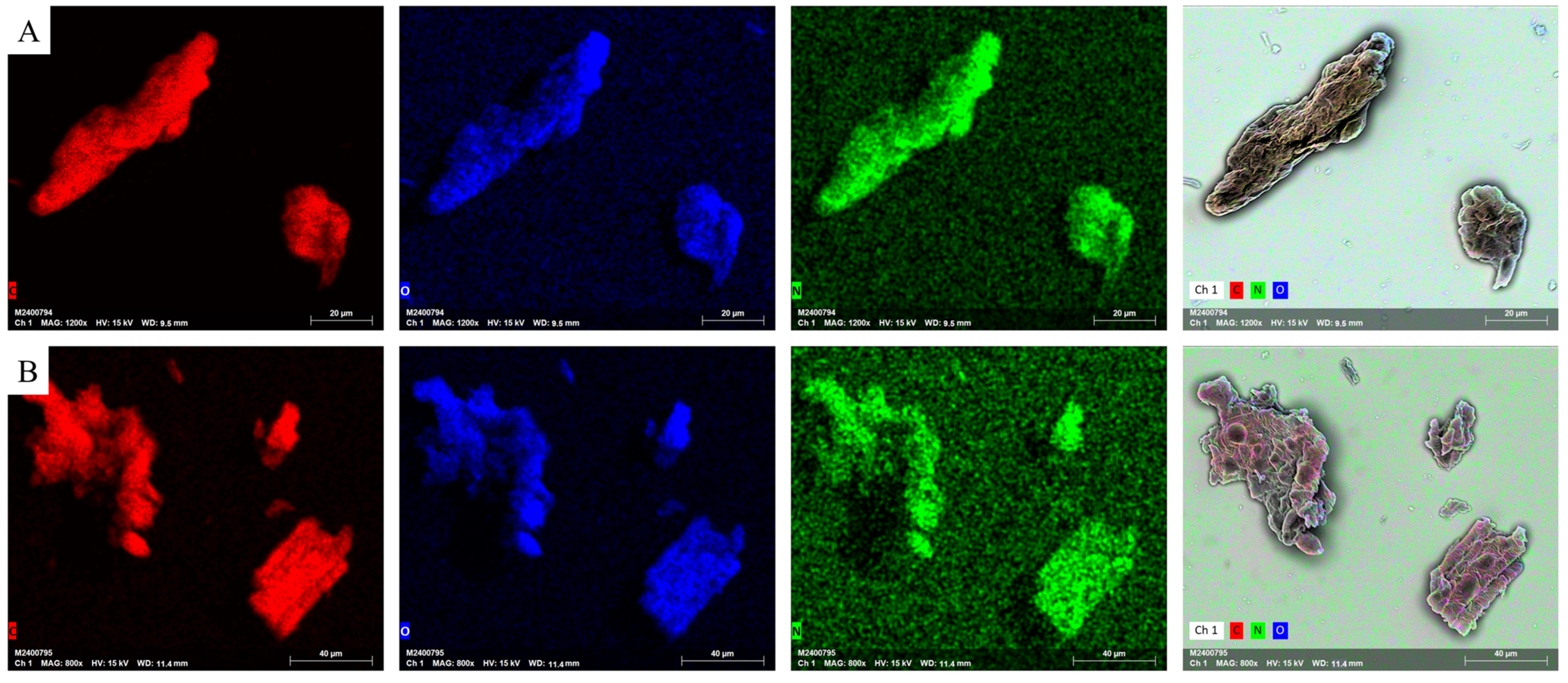

2.3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.4. Solid-State UV-Visible Analysis

2.5. Emission Spectroscopy of Spiropyran-Modified Celluloses (Cel-SP1 and Cel-SP2)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Raman Spectroscopy

3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy

3.3. Solid-State UV-Visible Analysis

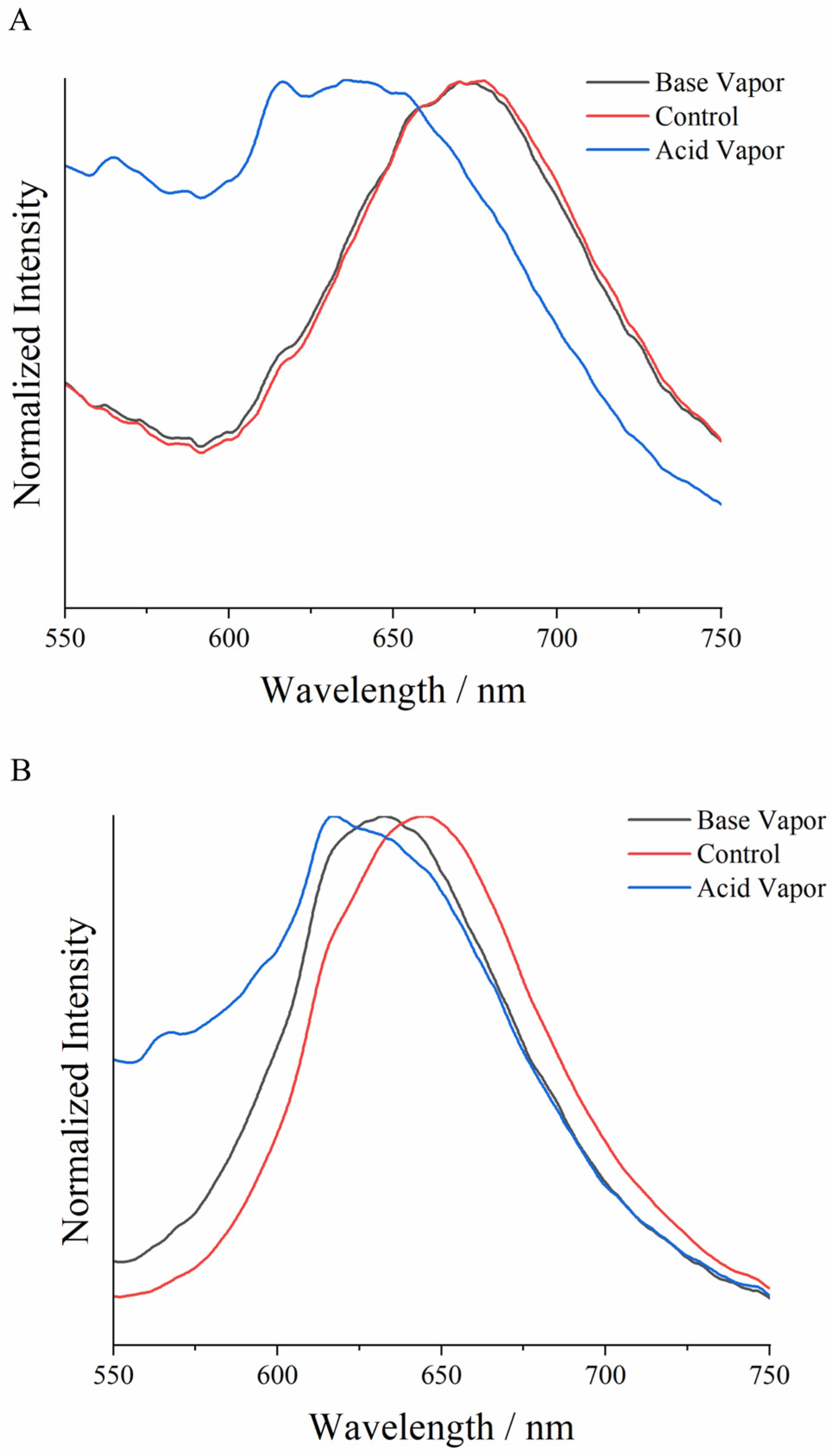

3.4. Solid-State Emission Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Idumah, C.I.; Odera, R.S.; Ezeani, E.O.; Low, J.H.; Tanjung, F.A.; Damiri, F.; Luing, W.S. Construction, characterization, properties and multifunctional applications of stimuli-responsive shape memory polymeric nanoarchitectures: A review. Polym. Plast. Technol. Mater. 2023, 62, 1247–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Png, Z.M.; Wang, C.-G.; Yeo, J.C.C.; Lee, J.J.C.; Surat’man, N.E.; Tan, Y.L.; Liu, H.; Wang, P.; Tan, B.H.; Xu, J.W.; et al. Stimuli-responsive structure–property switchable polymer materials. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 2023, 8, 1097–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Hua, D.; Xiong, R.; Huang, C. Bio-based stimuli-responsive materials for biomedical applications. Mater. Adv. 2023, 4, 458–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguez, F.B.; Moreira, O.B.O.; de Oliveira, M.A.L.; Denadai, Â.M.L.; de Oliveira, L.F.C.; De Sousa, F.B. Reversible electrospun fibers containing spiropyran for acid and base vapor sensing. J. Mater. Res. 2023, 38, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.A.; Okasha, R.M.; Khairou, K.S.; Afifi, T.H.; Mohamed, A.A.H.; Abd-El-Aziz, A.S. Design of thermochromic polynorbornene bearing spiropyran chromophore moieties: Synthesis, thermal behavior and Dielectric Barrier Discharge plasma treatment. Polymers 2017, 9, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Xiong, H.; Liang, H.; Chen, W.; Tian, Q.; Yan, M.; Su, H.; Royal, G. A New Spiropyran Hydrazone as an Unusual Colorimetric Sensor for Detection of Cu2+ and Cr3+ Based on Aggregation-Induced Enhancement Effects in Aqueous Solvent Mixtures. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202201868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, A.; Alinejad, Z.; Mahdavian, A.R. Facile and fast photosensing of polarity by stimuli-responsive materials based on spiropyran for reusable sensors: A physico-chemical study on the interactions. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 2017, 5, 6588–6600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, J.K.; Ghomi, A.R.; Karimipour, K.; Mahdavian, A.R. Progressive Readout Platform Based on Photoswitchable Polyacrylic Nanofibers Containing Spiropyran in Photopatterning with Instant Responsivity to Acid–Base Vapors. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 1613–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klajn, R. Spiropyran-based dynamic materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 148–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, J.K.; Balzade, Z.; Mahdavian, A.R. Spiropyran-based advanced photoswitchable materials: A fascinating pathway to the future stimuli-responsive devices. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2022, 51, 100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, A.; Bartkowski, M.; Giordani, S. Spiropyran-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 720087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marturano, V.; Kozlowska, J.; Bajek, A.; Giamberini, M.; Ambrogi, V.; Cerruti, P.; Garcia-Valls, R.; Montornes, J.M.; Tylkowski, B. Photo-triggered capsules based on lanthanide-doped upconverting nanoparticles for medical applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 398, 213013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, S.; Liu, L.; Li, L. Spiropyran-Functionalized Gold Nanoclusters with Photochromic Ability for Light-Controlled Fluorescence Bioimaging. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 2790–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinen, M.B.; Klein, P.; Sebastian, F.L.; Zorn, N.F.; Adamczyk, S.; Allard, S.; Scherf, U.; Zaumseil, J. Spiropyran-Functionalized Polymer–Carbon Nanotube Hybrids for Dynamic Optical Memory Devices and UV Sensors. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2020, 6, 2000717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Min, Y.; Ji, P.; Zhou, G.; Yin, H.; Qi, D.; Deng, H.; Hua, Z.; Chen, T. Light and temperature dual stimuli-responsive micelles from carbamate-containing spiropyran-based amphiphilic block copolymers: Fabrication, responsiveness and controlled release behaviors. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 200, 112493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Petrescu, F.I.T.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, G. Spiropyran-Based Soft Substrate with SPR, Anti-Reflection and Anti-NRET for Enhanced Visualization/Fluorescence Dual Response to Metal Ions. Materials 2023, 16, 3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W.; Jang, H.G.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, J. Force-induced fluorescence spectrum shift of spiropyran-based polymer for mechano-response sensing. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2023, 359, 114513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, A.; Guirado, G.; Sebastián, R.M.; Hernando, J. Spiropyran-based chromic hydrogels for CO2 absorption and detection. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1176661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisch, M.; Genovese, D.; Zaccheroni, N.; Schmidt, S.B.; Focarete, M.L.; Sommer, M.; Gualandi, C. Highly Sensitive, Anisotropic, and Reversible Stress/Strain-Sensors from Mechanochromic Nanofiber Composites. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1802813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chan, W.; Wang, Y.; You, Q.; Liu, C.; Zheng, J.; Li, J.; Yang, S.; Yang, R. Selective Tracking of Lysosomal Cu2+ Ions Using Simultaneous Target- and Location-Activated Fluorescent Nanoprobes. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, T.; Haq, F.; Farid, A.; Kiran, M.; Faisal, S.; Ullah, A.; Ullah, N.; Bokhari, A.; Mubashir, M.; Chuah, L.F.; et al. Challenges associated with cellulose composite material: Facet engineering and prospective. Environ. Res. 2023, 223, 115429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, F.V.; Souza, A.G.; Ajdary, R.; de Souza, L.P.; Lopes, J.H.; Correa, D.S.; Siqueira, G.; Barud, H.S.; Rosa, D.D.S.; Mattoso, L.H.C.; et al. Nanocellulose-based porous materials: Regulation and pathway to commercialization in regenerative medicine. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 29, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicho-Caranqui, J.; Vivanco, G.; Egas, D.A.; Chuya-Sumba, C.; Guerrero, V.H.; Ramirez-Cando, L.; Reinoso, C.; De Sousa, F.B.; Leon, M.; Ochoa-Herrera, V.; et al. Non-modified cellulose fibers for toxic heavy metal adsorption from water. Adsorption 2025, 31, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, S.; Li, J.; Wang, B.; Jin, M.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Han, Z.; Deng, L.; Qu, X.; et al. Insights into Hierarchical Structure–Property–Application Relationships of Advanced Bacterial Cellulose Materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2214327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akki, A.J.; Jain, P.; Kulkarni, R.; Rao, B.R.; Kulkarni, R.V.; Zameer, F.; Anjanapura, V.R.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Microbial biotechnology alchemy: Transforming bacterial cellulose into sensing disease—A review. Sens. Int. 2024, 5, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Wang, W.; Govindaraj, D.; Kang, S.; Vikesland, P.J. Recent advances in environmental science and engineering applications of cellulose nanocomposites. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 650–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.T.; Shahid, M.A.; Akter, S.; Ferdous, J.; Afroz, K.; Refat, K.R.I.; Faruk, O.; Jamal, M.S.I.; Uddin, M.N.; Samad, M.A.B. Cellulose and starch-based bioplastics: A review of advances and challenges for sustainability. Polym. Plast. Technol. Mater. 2024, 63, 1329–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simelane, N.P.; Olatunji, O.S.; John, M.J.; Andrew, J. Engineered transparent wood with cellulose matrix for glass applications: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 7, 100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Las-Casas, B.; Arantes, V. From production to performance: Tailoring moisture and oxygen barrier of cellulose nanomaterials for sustainable applications—A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 334, 122012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parthasarathi, R.; Bellesia, G.; Chundawat, S.P.S.; Dale, B.E.; Langan, P.; Gnanakaran, S. Insights into Hydrogen Bonding and Stacking Interactions in Cellulose. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 14191–14202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhena, T.C.; Sadiku, E.R.; Mochane, M.J.; Ray, S.S.; John, M.J.; Mtibe, A. Mechanical properties of cellulose nanofibril papers and their bionanocomposites: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 273, 118507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjabi, S.; Rad, J.K.; Salehi-Mobarakeh, H.; Mahdavian, A.R. Dual-chromic cellulose paper modified with nanocapsules containing leuco dye and spiropyran derivatives: A colorimetric portable chemosensor for detection of some heavy metal cations. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 111724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Wang, A.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, P.; Zhu, P. Light and pH dual-responsive spiropyran-based cellulose nanocrystals. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 11495–11502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, N.E.N.; Leão, C.A.S.; Alexis, F.; Ochoa-Herrera, V.; Zambrano-Romero, A.; Nobuyasu, R.S.; Miguez, F.B.; De Sousa, F.B. Exploiting Spiropyran Solvatochromism for Heavy Metal Ion Detection in Aqueous Solutions. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 36412–36420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miguez, F.B.; Trigueiro, J.P.C.; Lula, I.; Moraes, E.S.; Atvars, T.D.Z.; de Oliveira, L.F.C.; Alexis, F.; Nobuyasu, R.S.; De Sousa, F.B. Photochromic sensing of La3+ and Lu3+ ions using poly(caprolactone) fibers doped with spiropyran dyes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2024, 452, 115568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Vien, D.; Colthup, N.B.; Fateley, W.G.; Grasselli, J.G. A Summary of Characteristic Raman and Infrared Frequencies. In The Handbook of Infrared and Raman Characteristic Frequencies of Organic Molecules; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991; pp. 1–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.P. Analysis of Cellulose and Lignocellulose Materials by Raman Spectroscopy: A Review of the Current Status. Molecules 2019, 24, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, U.P. Beyond Crystallinity: Using Raman Spectroscopic Methods to Further Define Aggregated/Supramolecular Structure of Cellulose. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 857621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchenko, V.; Lomadze, N.; Santer, S.; Guskova, O. Spiropyran/Merocyanine Amphiphile in Various Solvents: A Joint Experimental–Theoretical Approach to Photophysical Properties and Self-Assembly. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görner, H. Photochromism of nitrospiropyrans: Effects of structure, solvent and temperature. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2001, 3, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, J.; Chen, L.; Tian, J. Generalized Solvent Effect on the Fluorescence Performance of Spiropyran for Advanced Quick Response Code Dynamic Anti-Counterfeiting Sensing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, C. Solvatochromic Dyes as Solvent Polarity Indicators. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 2319–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, C.; Welton, T. Solvents and Solvent Effects in Organic Chemistry, 4th ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, M.; Tsianou, M.; Alexandridis, P. Assessment of solvents for cellulose dissolution. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 228, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Society of Chemistry. Chapter 7. Solvatochromism. In Chromic Phenomena; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortekaas, L.; Chen, J.; Jacquemin, D.; Browne, W.R. Proton-Stabilized Photochemically Reversible E/Z Isomerization of Spiropyrans. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 6423–6430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortekaas, L.; Browne, W.R. The evolution of spiropyran: Fundamentals and progress of an extraordinarily versatile photochrome. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 3406–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimberger, L.; Prasad, S.K.K.; Peeks, M.D.; Andréasson, J.; Schmidt, T.W.; Beves, J.E. Large, Tunable, and Reversible pH Changes by Merocyanine Photoacids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 20758–20768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, M.; Banik, D.; Karak, A.; Manna, S.K.; Mahapatra, A.K. Spiropyran–Merocyanine Based Photochromic Fluorescent Probes: Design, Synthesis, and Applications. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 36988–37007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, K.M.; Bittmann, S.F.; Hayes, S.A.; Krawczyk, K.M.; Sarracini, A.; Corthey, G.; Dsouza, R.; Miller, R.J.D. Ultrafast signatures of merocyanine overcoming steric impedance in crystalline spiropyran. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

de Sá, D.D.S.; Trigueiro, J.P.C.; de Oliveira, L.F.C.; Barud, H.S.; Alexis, F.; Nobuyasu, R.S.; Miguez, F.B.; De Sousa, F.B. Spiropyran-Modified Cellulose for Dual Solvent and Acid/Base Vapor Sensing. Chemosensors 2026, 14, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010017

de Sá DDS, Trigueiro JPC, de Oliveira LFC, Barud HS, Alexis F, Nobuyasu RS, Miguez FB, De Sousa FB. Spiropyran-Modified Cellulose for Dual Solvent and Acid/Base Vapor Sensing. Chemosensors. 2026; 14(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010017

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Sá, Daniel D. S., João P. C. Trigueiro, Luiz F. C. de Oliveira, Hernane S. Barud, Frank Alexis, Roberto S. Nobuyasu, Flávio B. Miguez, and Frederico B. De Sousa. 2026. "Spiropyran-Modified Cellulose for Dual Solvent and Acid/Base Vapor Sensing" Chemosensors 14, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010017

APA Stylede Sá, D. D. S., Trigueiro, J. P. C., de Oliveira, L. F. C., Barud, H. S., Alexis, F., Nobuyasu, R. S., Miguez, F. B., & De Sousa, F. B. (2026). Spiropyran-Modified Cellulose for Dual Solvent and Acid/Base Vapor Sensing. Chemosensors, 14(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010017