In-Vehicle Gas Sensing and Monitoring Using Electronic Noses Based on Metal Oxide Semiconductor MEMS Sensor Arrays: A Critical Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. MOS MEMS Gas Sensors and Their Arrays

2.1. SnO2-Based MEMS Gas Sensor Array

2.2. ZnO-Based MEMS Gas Sensor Array

2.3. TiO2-Based MEMS Gas Sensor Array

3. Application of MEMS Preparation Technology in Sensor Array Manufacturing

3.1. Magnetron Sputtering

3.2. Other Key MEMS Preparation Technologies

3.3. Scalability and Cost Challenges in Synthesis Processes for MOX Sensing Films

3.4. Integration and Packaging Technology of Sensor Arrays

3.5. Development of CMOS-MEMS Integration Technology

3.6. From MEMS Sensor Chip to Complete E-Nose System

3.7. Advanced Material Engineering Strategies for Performance Enhancement in MEMS Sensor Arrays

3.7.1. Nanostructuring and Morphology Control

3.7.2. Noble Metal Decoration and Heterojunction Engineering

3.7.3. Photoactivation and Light-Assisted Sensing

3.7.4. Compatibility with MEMS Fabrication and Outlook

3.8. Emerging Substrate Materials for Automotive-Grade MEMS Gas Sensors

3.8.1. Glass Substrates

3.8.2. Ceramic Substrates

3.8.3. Polymer and Flexible Substrates

4. Recognition Algorithm

4.1. PCA

4.2. SVM

4.3. ANN

4.3.1. MLP

4.3.2. ELM

4.3.3. CNN

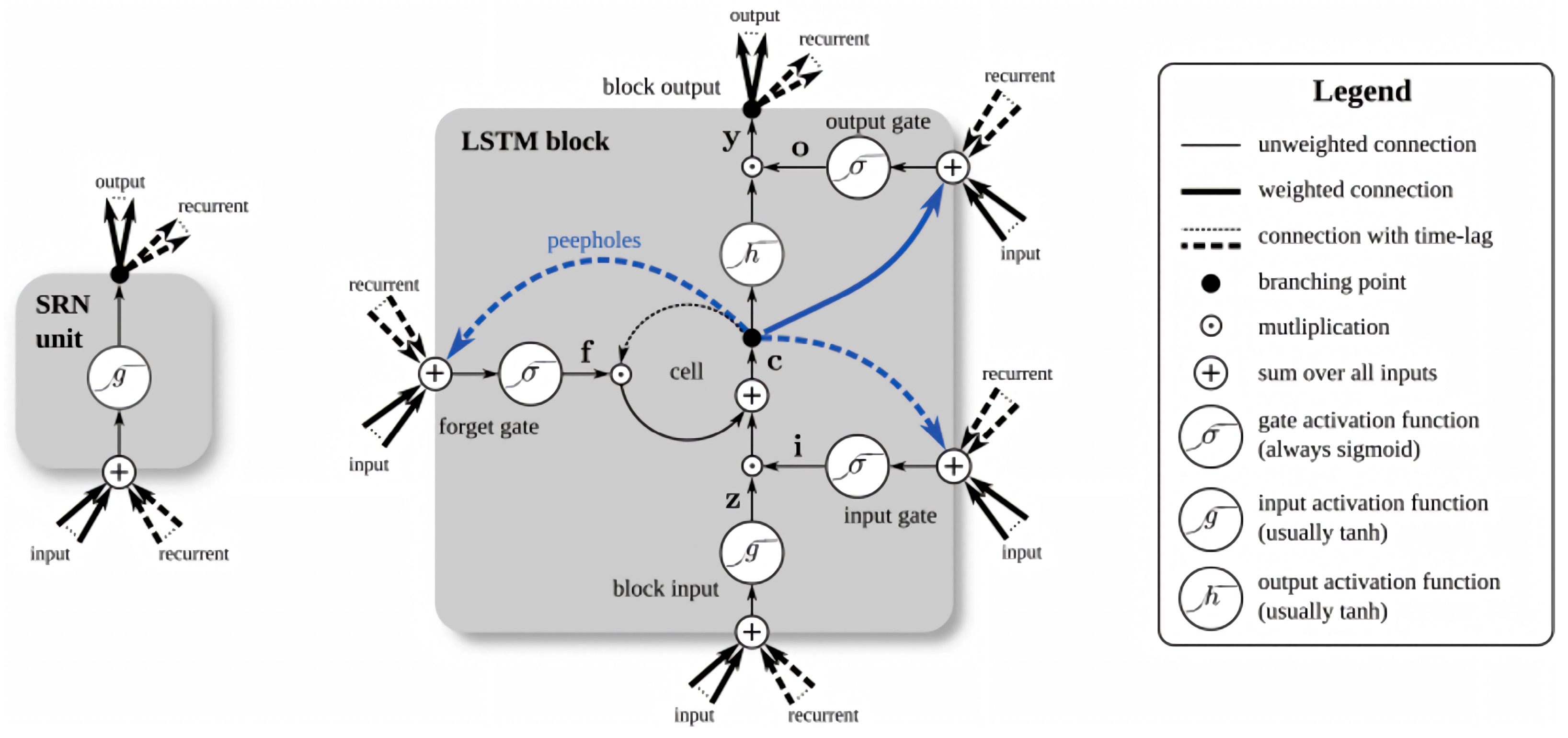

4.3.4. LSTM

4.4. Advanced Circuit-Algorithm Synergy and Future Integration Strategies

5. Challenges and Benchmarking for Real-World In-Vehicle Deployment

6. Conclusions and Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MEMS | Micro-Electro-Mechanical System |

| MOS | Metal Oxide Semiconductor |

| VOCs | Volatile Organic Compounds |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| GC-O | Gas Chromatography–Olfactometry |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| ELM | Extreme Learning Machine |

| SnO2 | Tin Oxide |

| ZnO | Zinc Oxide |

| TiO2 | Titanium Dioxide |

| NOx | Nitrogen Oxides |

| CMOS | Complementary Metal Oxide Semiconductor |

| Pd | Palladium |

| Au | Gold |

| NiO | Nickel Oxide |

| WO3 | Tungsten Trioxide |

| FE-SEM | Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| XPS | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy |

| ppm | Parts Per Million |

| ppb | Parts Per Billion |

| ppt | Parts Per Trillion |

| CuO | Copper Oxide |

| Al2O3 | Aluminum Oxide |

| CVD | Chemical Vapor Deposition |

| RT | Room temperature |

| AACVD | Aerosol Assisted Chemical Vapor Deposition |

| ALD | Atomic Layer Deposition |

| TMAH | Tetramethylammonium Hydroxide |

| KOH | Potassium Hydroxide |

| IDEs | Interdigitated Electrodes |

| WLP | Wafer-Level Packaging |

| SOI | Silicon on Insulator |

| PECVD | Plasma-Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition |

| BCD | Bipolar-CMOS-DMOS |

| RSD | Relative Standard Deviation |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| Bi-LSTM | Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory |

| ConvLSTM | Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| KNN | k-Nearest Neighbor |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| SNN | Spiking Neural Network |

| ASIC | Application-Specific Integrated Circuit |

| FPGA | Field-Programmable Gate Array |

| STDP | Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity |

| LOD | Limit of Detection |

| PPMCC | Pearson Product Moment Correlation Coefficient |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| CMUT | Capacitive Micromachined Ultrasonic Transducer |

| CH2O | Formaldehyde |

| CH4O | Methanol |

| NDIR | Non-dispersive infrared |

| PID | Photoionization Detector |

References

- Yoshida, T.; Matsunaga, I.; Tomioka, K.; Kumagai, S. Interior Air Pollution in Automotive Cabins by Volatile Organic Compounds Diffusing from Interior Materials: I. Survey of 101 Types of Japanese Domestically Produced Cars for Private Use. Indoor Built Environ. 2006, 15, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczurek, A.; Maciejewska, M. Categorisation for Air Quality Assessment in Car Cabin. Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 2016, 48, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchecker, F.; Loos, H.M.; Buettner, A. Volatile Compounds in the Vehicle-Interior: Odorants of an Aqueous Cavity Preservation and Beyond. In Proceedings of the Progress in Flavour Research: Proceedings of the 16th Weurman Flavour Research Symposium, Dijon, France, 4–6 May 2021; pp. 289–292. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Mo, J.; Sundell, J.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, Y. Health Risk Assessment of Inhalation Exposure to Formaldehyde and Benzene in Newly Remodeled Buildings, Beijing. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, W.-T. An Overview of Health Hazards of Volatile Organic Compounds Regulated as Indoor Air Pollutants. Rev. Environ. Health 2019, 34, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadava, R.N.; Bhatt, V. Carbon Monoxide: Risk Assessment, Environmental, and Health Hazard. In Hazardous Gases; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Moufid, M.; Bouchikhi, B.; Tiebe, C.; Bartholmai, M.; El Bari, N. Assessment of Outdoor Odor Emissions from Polluted Sites Using Simultaneous Thermal Desorption-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (TD-GC-MS), Electronic Nose in Conjunction with Advanced Multivariate Statistical Approaches. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 256, 118449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Feng, Z.; Zheng, H.; Yao, Z.; Weng, X.; Wang, F.; Chang, Z. Development Trend of Electronic Nose Technology in Closed Cabins Gas Detection: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchecker, F.; Baum, A.; Loos, H.M.; Buettner, A. Follow Your Nose-Traveling the World of Odorants in New Cars. Indoor Air 2022, 32, e13014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharyya, S.; Jana, B.; Nag, S.; Saha, G.; Guha, P.K. Single Resistive Sensor for Selective Detection of Multiple VOCs Employing SnO2 Hollowspheres and Machine Learning Algorithm: A Proof of Concept. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 321, 128484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, S.; Minaei, S.; Ghasemi-Varnamkhasti, M. Application of Electronic Nose Systems for Assessing Quality of Medicinal and Aromatic Plant Products: A Review. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2016, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Wan, L.; Jian, Y.; Ren, C.; Jin, K.; Su, X.; Bai, X.; Haick, H.; Yao, M.; Wu, W. Electronic Noses: From Advanced Materials to Sensors Aided with Data Processing. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2019, 4, 1800488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asri, M.I.A.; Hasan, M.N.; Fuaad, M.R.A.; Yunos, Y.M.; Ali, M.S.M. MEMS Gas Sensors: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 18381–18397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; You, R. Research Progress of Electronic Nose Technology in Exhaled Breath Disease Analysis. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2023, 9, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabih, A.A.S.; Dennis, J.O.; Ahmed, A.Y.; Md Khir, M.H.; Ahmed, M.G.A.; Idris, A.; Mian, M.U. MEMS-Based Acetone Vapor Sensor for Non-Invasive Screening of Diabetes. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 9486–9500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Liu, R.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Liu, Y.; Sun, J.; Huang, K.; Zhong, L.; Wang, J.; et al. A Portable Breath Acetone Analyzer Using a Low-Power and High-Selectivity MEMS Gas Sensor Based on Pd/In2O3-Decorated SnO2 Nanocomposites. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 439, 137854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-Y.; Wong, D.-M.; Fang, C.-Y.; Chiu, C.-I.; Chou, T.-I.; Wu, C.-C.; Chiu, S.-W.; Tang, K.-T. Development of an Electronic-Nose System for Fruit Maturity and Quality Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Applied System Invention (ICASI), Chiba, Japan, 13–17 April 2018; pp. 1129–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Love, C.; Nazemi, H.; El-Masri, E.; Ambrose, K.; Freund, M.S.; Emadi, A. A Review on Advanced Sensing Materials for Agricultural Gas Sensors. Sensors 2021, 21, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molleman, B.; Alessi, E.; Passaniti, F.; Daly, K. Evaluation of the Applicability of a Metal Oxide Semiconductor Gas Sensor for Methane Emissions from Agriculture. Inf. Process. Agric. 2024, 11, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, M.; Ji, X.; Chang, J.; Deng, Z.; Meng, G. Recognition Algorithms in E-Nose: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 20460–20472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.-H.; Liu, K.-X.; Xu, X.-H.; Meng, Q.-H. Odor Evaluation of Vehicle Interior Materials Based on Portable E-Nose. In Proceedings of the 2020 39th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Shenyang, China, 27–29 July 2020; pp. 2998–3003. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, G.C.A.; Abu-Libdeh, A. Electronic Nose for Gas Sensing Applications in Autonomous Vehicles. In Proceedings of the UWill Discover Student Research Conference, Windsor, ON, Canada, 18–24 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, S.; Wilk-Jakubowski, J.Ł.; Ciopiński, L.; Pawlik, Ł.; Wilk-Jakubowski, G.; Mihalev, G. Modern Trends in the Application of Electronic Nose Systems: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Lee, J.-H. Highly Sensitive and Selective Gas Sensors Using P-Type Oxide Semiconductors: Overview. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 192, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretu, V.; Postica, V.; Mishra, A.K.; Hoppe, M.; Tiginyanu, I.; Mishra, Y.K.; Chow, L.; De Leeuw, N.H.; Adelung, R.; Lupan, O. Synthesis, Characterization and DFT Studies of Zinc-Doped Copper Oxide Nanocrystals for Gas Sensing Applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 6527–6539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Yu, Q.; Kebeded, M.A.; Zhuang, Y.; Huang, S.; Jiao, M.; He, X. Advances in Modification of Metal and Noble Metal Nanomaterials for Metal Oxide Gas Sensors: A Review. Rare Met. 2025, 44, 1443–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yin, L.; Zhang, L.; Xiang, D.; Gao, R. Metal Oxide Gas Sensors: Sensitivity and Influencing Factors. Sensors 2010, 10, 2088–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, L.; Sosada-Ludwikowska, F.; Steinhauer, S.; Singh, V.; Grammatikopoulos, P.; Köck, A. SnO2-Based CMOS-Integrated Gas Sensor Optimized by Mono-, Bi-, and Trimetallic Nanoparticles. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Kang, Y.; Fang, W.; Zhu, B.; Song, Z. Tuning Gas Sensing Properties through Metal-Nanocluster Functionalization of 3D SnO2 Nanotube Arrays for Selective Gas Detection. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 6084–6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Bermak, A.; Chan, P.C.H.; Yan, G.-Z. A 4×4 Tin Oxide Gas Sensor Array with On-Chip Signal Pre-Processing. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference on Microelectronics, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, 11–13 December 2006; pp. 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, P.G.; Masuda, Y. Nanosheet-Type Tin Oxide Gas Sensor Array for Mental Stress Monitoring. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z.; Song, Z.; Zhou, X.; Han, N.; Chen, Y. Sputtered SnO2:NiO Thin Films on Self-Assembled Au Nanoparticle Arrays for MEMS Compatible NO2 Gas Sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 278, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Shen, W.; Gao, Y.; Lv, D.; Song, W.; Tan, R. Optimization of SnO2-Based MEMS Sensor Array for Expeditious and Precise Categorization of Meat Types and Freshness Status. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2025, 391, 116680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, R.; Li, Y.; Tian, J.; Tan, C.; Chen, S.; Lei, M.; Xie, F.; Guo, X.; Zhang, S. Cross-Interference of VOCs in SnO2-Based NO Sensors. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, K.G.; Umadevi, G.; Parne, S.; Pothukanuri, N. Zinc Oxide Based Gas Sensors and Their Derivatives: A Critical Review. J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 3906–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Tan, R.; Shen, W.; Lv, D.; Yin, J.; Chen, W.; Fu, H.; Song, W. Inkjet-Printed ZnO-Based MEMS Sensor Array Combined with Feature Selection Algorithm for VOCs Gas Analysis. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 382, 133555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Rong, Q.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Jiao, M.; Song, J.; Wang, C.; Guo, Y. ZnO Nanoparticle-Based MEMS Sensors for H2 S Detection. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 11595–11604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.-L.; Young, S.-J.; Huang, Y.-R.; Arya, S.; Chu, T.-T. Highly Sensitive Ethanol Gas Sensors of Au Nanoparticle-Adsorbed ZnO Nanorod Arrays via a Photochemical Deposition Treatment. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2025, 7, 2327–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarjuna, Y.; Hsiao, Y.-J. CuO/ZnO Heterojunction Nanostructured Sensor Prepared on MEMS Device for Enhanced H2 S Gas Detection. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 067521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, H.; Cai, Y.; Zhao, J.; Gao, Z.; Song, Y.-Y. The Challenges and Opportunities for TiO2 Nanostructures in Gas Sensing. ACS Sens. 2024, 9, 1644–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouktif, B.; Rashid, M.; Hajjaji, A.; Choubani, K.; Alrasheedi, N.H.; Louhichi, B.; Dimassi, W.; Ben Rabha, M. Synthesis and Characterization of TiO2 Nanotubes for High-Performance Gas Sensor Applications. Crystals 2024, 14, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, M.; Ghossoub, Y.; Noel, L.; Li, P.-H.; Tsai, H.-Y.; Soppera, O.; Zan, H.-W. Highly Efficient UV-Activated TiO2 /SnO2 Surface Nano-Matrix Gas Sensor: Enhancing Stability for Ppb-Level NOx Detection at Room Temperature. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 14670–14681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, A.; Jen, A.K.-Y. Reducing Cross-Sensitivity of TiO2-(B) Nanowires to Humidity Using Ultraviolet Illumination for Trace Explosive Detection. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, P.C.; Sério, S. Recent Applications and Future Trends of Nanostructured Thin Films-Based Gas Sensors Produced by Magnetron Sputtering. Coatings 2024, 14, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooja; Dahiya, R.; Sheokand, A.; Bulla, M.; Sindhu, S.; Rani, P.; Jeet, K.; Kumar, V. Fabrication of ZnO Thin Film Sensor Using Sputtering for Low-Level NO2 Detection. Indian J. Pure Appl. Phys. 2025, 63, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Park, J.-S.; Lee, H.-J. Pt-Doped SnO2 Thin Film Based Micro Gas Sensors with High Selectivity to Toluene and HCHO. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 248, 1011–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanmathi, M.; Senthil Kumar, M.; Ismail, M.M.; Senguttuvan, G. Optimization of Process Parameters for Al-Doping Back Ground on CO Gas Sensing Characteristics of Magnetron-Sputtered TiO2 Sensors. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 106423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, C.; Srivastava, S.; Dhanda, A.; Singh, P. Pd-Decorated WO3 Thin Films Deposited by DC Reactive Magnetron Sputtering for Highly Selective NO Gas with Temperature-Dependent Tunable p-n Switching. Materialia 2025, 40, 102413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelson, J.R.; Girolami, G.S. New Strategies for Conformal, Superconformal, and Ultrasmooth Films by Low Temperature Chemical Vapor Deposition. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2020, 38, 030802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Pullar, R.C.; Parkin, I.P.; Piccirillo, C. Nanostructured Titanium Dioxide Coatings Prepared by Aerosol Assisted Chemical Vapour Deposition (AACVD). J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem. 2020, 400, 112727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lou, C.; Lei, G.; Lu, G.; Pan, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J. Regulation of Electronic Properties of ZnO/In2 O3 Heterospheres via Atomic Layer Deposition for High Performance NO2 Detection. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 5060–5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarnalatha, V.; Pal, P.; Pandey, A.K.; Narasimha Rao, A.V.; Xing, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Sato, K. Systematic Study of the Etching Characteristics of Si{111} in Modified TMAH. Micro Nano Lett. 2020, 15, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presmanes, L.; Thimont, Y.; El Younsi, I.; Chapelle, A.; Blanc, F.; Talhi, C.; Bonningue, C.; Barnabé, A.; Menini, P.; Tailhades, P. Integration of P-CuO Thin Sputtered Layers onto Microsensor Platforms for Gas Sensing. Sensors 2017, 17, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, T.; Feng, S.; Qin, S.; Zhang, T. Heteronanostructural Metal Oxide-Based Gas Microsensors. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2022, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, G.F.; Cavanagh, L.M.; Afonja, A.; Binions, R. Metal Oxide Semi-Conductor Gas Sensors in Environmental Monitoring. Sensors 2010, 10, 5469–5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Arbia, M.; Helal, H.; Comini, E. Recent Advances in Low-Dimensional Metal Oxides via Sol-Gel Method for Gas Detection. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, H. Inkjet Printing of MOx-Based Heterostructures for Gas Sensing and Safety Applications—Recent Trends, Challenges, and Future Scope. Complex Compos. Met. Oxides Gas. VOC Humidity Sens. 2024, 2, 133–157. [Google Scholar]

- Sanketh, H.S.; Vijayan, A.; Poornesh, P.; Rao, A. Scalable, Sensitive, Smart: The Role of Inkjet Printing in next-Generation Chemiresistive Gas Sensors. Mater. Res. Express 2025, 12, 092001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, K.S.; ALzanganawee, J.; Kamil, A.A. A Novel Approach to Low-Temperature Gas Sensing Using Sol-Gel Spin-Coated (NiO:ZnO:SnO2) Thin Films for NO2, H2S, and NH3 Detection. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2025, 115, 688–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarjuna, Y.; Lin, J.-C.; Wang, S.-C.; Hsiao, W.-T.; Hsiao, Y.-J. AZO-Based ZnO Nanosheet MEMS Sensor with Different Al Concentrations for Enhanced H2S Gas Sensing. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Min, T.U. Advances in the Application of Atomic Layer Deposition in Gas Sensors. J. Funct. Mater. Devices. 2025. Available online: https://www.jfmd.net.cn/en/article/id/ae95a38e-1b97-4ec9-8396-4acb68200273.

- Michael, A.; Chuang, I.Y.-H.; Kwok, C.Y.; Omaki, K. Low-Thermal-Budget Electrically Active Thick Polysilicon for CMOS-First MEMS-Last Integration. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2024, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielewczyk, L.; Galle, L.; Niese, N.; Grothe, J.; Kaskel, S. Precursor-Derived Sensing Interdigitated Electrode Microstructures Based on Platinum and Nano Porous Carbon. ChemistryOpen 2024, 13, e202400179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, M.; Golan, G.; Vaiana, M.; Bruno, G.; Castagna, M.E.; Stolyarova, S.; Blank, T.; Nemirovsky, Y. Wafer-Level Packaged CMOS-SOI-MEMS Thermal Sensor at Wide Pressure Range for IoT Applications. In Proceedings of the 7th International Electronic Conference on Sensors and Applications, MDPI Online, 15–30 November 2020; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Witvrouw, A. CMOS–MEMS Integration Today and Tomorrow. Scr. Mater. 2008, 59, 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, K.H.H.; Tan, O.K. Microhotplates for Metal Oxide Semiconductor Gas Sensor Applications—Towards the CMOS-MEMS Monolithic Approach. Micromachines 2018, 9, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirzada, M.R.; Khan, Y.; Ehsan, M.K.; Rehman, A.U.; Jamali, A.A.; Khatri, A.R. Prediction of Surface Roughness as a Function of Temperature for SiO2 Thin-Film in PECVD Process. Micromachines 2022, 13, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, S.-H. CMOS MEMS Design and Fabrication Platform. Front. Mech. Eng. 2022, 8, 894484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Sun, F.; Dai, Y.; Wang, S.; Bai, Y.; Li, L.; Li, T.; Zhang, T.; Qin, S. “Top-down” and “Bottom-up” Strategies for Wafer-Scaled Miniaturized Gas Sensors Design and Fabrication. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2020, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, T.; Zhang, G.; Gao, R.; Gao, C.; Wang, Z.; Xuan, F. Rational Design and Fabrication of MEMS Gas Sensors With Long-Term Stability: A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e11555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, T.T.; Li, Y.-C.; Le, Q.T.; Chueh, Y.-L.; Fang, W. Design and Implementation of CMOS-MEMS Schottky Gas Sensor With Asymmetric Metal Contacts for Performance Enhancement at Room Temperature. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 12587–12598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Dai, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, M. Pulse-Driven MEMS Gas Sensor Combined with Machine Learning for Selective Gas Identification. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2025, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, D.; Wu, H. Electronic Noses: From Gas-Sensitive Components and Practical Applications to Data Processing. Sensors 2024, 24, 4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Boussaid, F.; Zhang, D.; Pan, X.; Zhao, H.; Bermak, A.; Tsui, C.-Y.; Wang, X.; Fan, Z. Ultra-Low-Power Smart Electronic Nose System Based on Three-Dimensional Tin Oxide Nanotube Arrays. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 6079–6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.-W.; He, S.-Y.; Huang, Z.-Y.; Wang, Y.-W.; Zhang, X.-F.; Ou, L.-X.; Zhang, D.W.; Yu, H.-X.; Lu, H.-L. Fabrication of MEMS-Based TiO2/SnO2 Core-Shell Nanowires Sensor for Enhanced H2S Sensing. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 31703–31712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Woo, C.Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.M.; Kim, N.-Y.; Lee, H.W.; Oh, J.-W. Recent Progress of Gas Sensors toward Olfactory Display Development. Nano Converg. 2025, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas Alam, M.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, S.; Mohammad Junaid, P.; Awad, M. VOC Detection with Zinc Oxide Gas Sensors: A Review of Fabrication, Performance, and Emerging Applications. Electroanalysis 2025, 37, e202400246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.-Y.; Ou, L.-X.; Mao, L.-W.; Wu, X.-Y.; Liu, Y.-P.; Lu, H.-L. Advances in Noble Metal-Decorated Metal Oxide Nanomaterials for Chemiresistive Gas Sensors: Overview. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023, 15, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Li, Z.; Yi, J. Selective Detection of Parts-per-Billion H2S with Pt-Decorated ZnO Nanorods. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 333, 129545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanga, S.R.; Sarada, V.; Yadav, A.B. Sol–Gel Drop Coated ZnO/SnO2 Nanostructure Thin Film Heterojunction on Glass Substrate for Ethanol Sensing. Appl. Phys. A 2025, 131, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, M.; Park, S.; Ahn, J.; Kim, I. Materials Engineering for Light-Activated Gas Sensors: Insights, Advances, and Future Perspectives. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e08204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasriddinov, A.; Zairov, R.; Rumyantseva, M. Light-Activated Semiconductor Gas Sensors: Pathways to Improve Sensitivity and Reduce Energy Consumption. Front. Chem. 2025, 13, 1538217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.-Y.; Zheng, Z.-W.; Wang, Y.-W.; Zhang, Y.-H.; Huang, Z.-Y.; Zhang, X.-F.; Lu, H.-L.; Yu, H.-X. Low-Power MEMS Gas Sensor Based on TiO2/SnO2 Core–Shell Nanorods for Ultrasensitive H2 S Detection. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2025, 7, 9881–9889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, T.R.; Choi, J.; Bandodkar, A.J.; Krishnan, S.; Gutruf, P.; Tian, L.; Ghaffari, R.; Rogers, J.A. Bio-Integrated Wearable Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 5461–5533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Dai, H.; Chen, F.; Liu, S.; Du, X.; Li, B.; Zhu, M.; Xue, G. Development of Glass-Substrate-Based MEMS Micro-Hotplate with Low-Power Consumption and TGV Structure Through Anodic Bonding and Glass Thermal Reflow. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 37th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), Austin, TX, USA, 21–25 January 2024; pp. 891–894. [Google Scholar]

- Andrysiewicz, W.; Krzeminski, J.; Skarżynski, K.; Marszalek, K.; Sloma, M.; Rydosz, A. Flexible Gas Sensor Printed on a Polymer Substrate for Sub-Ppm Acetone Detection. Electron. Mater. Lett. 2020, 16, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lei, M.; Xia, X. Research Progress of MEMS Gas Sensors: A Comprehensive Review of Sensing Materials. Sensors 2024, 24, 8125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; He, Q.; Shen, D.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, W.; Ono, T.; Jiang, Y. Microfabrication of Functional Polyimide Films and Microstructures for Flexible MEMS Applications. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2023, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, F.; Zhou, F.; Wang, Z.; Wei, L.; Hu, J.; Dong, L.; Ma, Y.; Wang, M.; Jia, S.; Chen, X.; et al. Synthesizing Metal Oxide Semiconductors on Doped Si/SiO2 Flexible Fiber Substrates for Wearable Gas Sensing. Research 2023, 6, 0100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah Nia, E.; Kouki, A. Ceramics for Microelectromechanical Systems Applications: A Review. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, B.; Shi, Y.; Li, J.; Tang, J.; Feng, Q. Design, Simulation, and Fabrication of Multilayer Al2O3 Ceramic Micro-Hotplates for High Temperature Gas Sensors. Sensors 2022, 22, 6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharbanda, D.K.; Suri, N.; Khanna, P.K. Design, Fabrication and Characterization of Laser Patterned LTCC Micro Hotplate with Stable Interconnects for Gas Sensor Platform. Microsyst. Technol. 2019, 25, 2197–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chai, Y.; Wang, S.; Yu, J.; Jiang, S.; Zhu, W.; Fang, Z.; Li, B. Recent Study Advances in Flexible Sensors Based on Polyimides. Sensors 2023, 23, 9743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainani, K.L. Introduction to Principal Components Analysis. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 6, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzyniak, J. Quantification of Volatile Compounds in Mixtures Using a Single Thermally Modulated MOS Gas Sensor with PCA–ANN Data Processing. Sensors 2025, 25, 6913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Gao, S.; Deng, H.; Liu, H.; Hou, D.; Lu, Q.; He, X.; Huang, S. Surface Electronic Structure Modulation of PdO/SnO2 through Loading Pd for Superior Hydrogen Sensing Performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 515, 163694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, I.-H.; Jin, J.-H.; Min, N.K. A Micromachined Metal Oxide Composite Dual Gas Sensor System for Principal Component Analysis-Based Multi-Monitoring of Noxious Gas Mixtures. Micromachines 2019, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, N.; Wei, X.; Cao, S.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, T. Nanoscale Bimetallic AuPt-Functionalized Metal Oxide Chemiresistors: Ppb-Level and Selective Detection for Ozone and Acetone. ACS Sens. 2022, 7, 2178–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- War, M.; Bouchikhi, B.; Zaim, O.; Lagdali, N.; Ajana, F.Z.; El Bari, N. Electronic Nose System Based on Metal Oxide Semiconductor Sensors for the Analysis of Volatile Organic Compounds in Exhaled Breath for the Discrimination of Liver Cirrhosis Patients and Healthy Controls. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Cao, X.; Li, C.; Zhou, M.; Liu, T.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L. A Review of Machine Learning-Assisted Gas Sensor Arrays in Medical Diagnosis. Biosensors 2025, 15, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, G.; Kim, M.; Song, W.; Myung, S.; Lee, S.S.; An, K.-S. Impact of a Diverse Combination of Metal Oxide Gas Sensors on Machine Learning-Based Gas Recognition in Mixed Gases. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 23155–23162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-Vector Networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Jia, Y.; Su, X.; Zhao, B.; Jiang, J.; Gao, L.; Zhu, X.; Shi, Y. CH4, C2H6, and C2H4 Multi-Gas Sensing Based on Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy and SVM Algorithm. Sensors 2025, 25, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sajana, S.; Varma, P.; Sreelekha, G.; Adak, C.; Shukla, R.P.; Kamble, V.B. Metal Oxide-Based Gas Sensor Array for VOCs Determination in Complex Mixtures Using Machine Learning. Microchim. Acta 2024, 191, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lin, S.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, J. Several ML Algorithms and Their Feature Vector Design for Gas Discrimination and Concentration Measurement with an Ultrasonically Catalyzed MOX Sensor. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamori, T.; Fujiwara, S.; Takeda, A. Breakdown Point of Robust Support Vector Machine. Entropy 2014, 19, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, P.; Xiao, K.; Meng, X.; Han, L.; Yu, C. Sensor Drift Compensation Based on the Improved LSTM and SVM Multi-Class Ensemble Learning Models. Sensors 2019, 19, 3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J. ANN vs. SVM: Which One Performs Better in Classification of MCCs in Mammogram Imaging. Knowl. Based Syst. 2012, 26, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.; Lee, S. A Selective AQS System with Artificial Neural Network in Automobile. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2008, 130, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Zeng, M.; Yang, J.; Su, Y.; Hu, N.; Yang, Z. Classification and Concentration Prediction of VOCs With High Accuracy Based on an Electronic Nose Using an ELM-ELM Integrated Algorithm. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 14458–14469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, J.; Li, X. Identification of Formaldehyde under Different Interfering Gas Conditions with Nanostructured Semiconductor Gas Sensors. Nanomater. Nanotechnol. 2015, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, M.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, Z. Heterogeneous Data Fusion Model for Gas Leakage Detection. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2025, 98, 105767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Liu, Y. Early-Stage Gas Identification Using Convolutional Long Short-Term Neural Network with Sensor Array Time Series Data. Sensors 2021, 21, 4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Li, Y.; Jin, R.; Li, Q. Toward Accurate Odor Identification and Effective Feature Learning With an AI-Empowered Electronic Nose. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 4735–4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M.-C.; Balas, V.E.; Perescu-Popescu, L.; Mastorakis, N. Multilayer Perceptron and Neural Networks. Wseas Trans. Circuits Syst. 2009, 8, 579–588. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, C.C.; Kamarudin, L.M.; Zakaria, A.; Nishizaki, H.; Ramli, N.; Mao, X.; Syed Zakaria, S.M.M.; Kanagaraj, E.; Abdull Sukor, A.S.; Elham, M.F. Real-Time In-Vehicle Air Quality Monitoring System Using Machine Learning Prediction Algorithm. Sensors 2021, 21, 4956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukor, A.S.A.; Cheik, G.C.; Kamarudin, L.M.; Mao, X.; Nishizaki, H.; Zakaria, A.; Syed Zakaria, S.M.M. Predictive Analysis of In-Vehicle Air Quality Monitoring System Using Deep Learning Technique. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Guo, L.; Wang, M.; Su, C.; Wang, D.; Dong, H.; Chen, J.; Wu, W. Review on Algorithm Design in Electronic Noses: Challenges, Status, and Trends. Intell. Comput. 2023, 2, 0012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.-B.; Zhu, Q.-Y.; Siew, C.-K. Extreme Learning Machine: Theory and Applications. Neurocomputing 2006, 70, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Xu, X.; Nie, R. Extreme Learning Machine and Its Applications. Neural Comput. Appl. 2014, 25, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.-B.; Zhou, H.; Ding, X.; Zhang, R. Extreme Learning Machine for Regression and Multiclass Classification. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part B Cybern. 2011, 42, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.-B.; Chen, L.; Siew, C.-K. Universal Approximation Using Incremental Constructive Feedforward Networks with Random Hidden Nodes. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2006, 17, 879–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, H.T.; Won, Y. Weighted Least Squares Scheme for Reducing Effects of Outliers in Regression Based on Extreme Learning Machine. Int. J. Digit. Content Technol. Its Appl. 2008, 2, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Yao, P.; Akbar, S.A. Detection of Formaldehyde in Mixed VOCs Gases Using Sensor Array With Neural Networks. IEEE Sens. J. 2016, 16, 6081–6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaría, J.; Fadhel, M.A.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of Deep Learning: Concepts, CNN Architectures, Challenges, Applications, Future Directions. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hu, X.; Li, A.; Kometani, R.; Yamada, I.; Sashida, K.; Noma, M.; Nakanishi, K.; Fukuda, Y.; Takemori, T.; et al. Identification of Binary Gases’ Mixtures from Time-Series Resistance Fluctuations: A Sensitivity-Controllable SnO2 Gas Sensor-Based Approach Using 1D-CNN. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2023, 349, 114070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, G.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, P. An Electronic Nose for Harmful Gas Early Detection Based on a Hybrid Deep Learning Method H-CRNN. Microchem. J. 2023, 195, 109464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greff, K.; Srivastava, R.K.; Koutnik, J.; Steunebrink, B.R.; Schmidhuber, J. LSTM: A Search Space Odyssey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2017, 28, 2222–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Song, S.; Li, S.; Ma, L.; Pan, S.; Han, L. Research on Gas Concentration Prediction Models Based on LSTM Multidimensional Time Series. Energies 2019, 12, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, A.; Schmidhuber, J. Framewise Phoneme Classification with Bidirectional LSTM and Other Neural Network Architectures. Neural Netw. 2005, 18, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Yeung, D.-Y.; Wong, W.; Woo, W. Convolutional LSTM Network: A Machine Learning Approach for Precipitation Nowcasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 9, 802–810. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, H.-K.; Kwon, C.H.; Kim, S.-R.; Yun, D.H.; Lee, K.; Sung, Y.K. Portable Electronic Nose System with Gas Sensor Array and Artificial Neural Network. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2000, 66, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nake, A.; Dubreuil, B.; Raynaud, C.; Talou, T. Outdoor in Situ Monitoring of Volatile Emissions from Wastewater Treatment Plants with Two Portable Technologies of Electronic Noses. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2005, 106, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, S.; Strobel, P.; Siadat, M.; Lumbreras, M. Evaluation of Unpleasant Odor with a Portable Electronic Nose. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2008, 28, 949–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matatagui, D.; Bahos, F.A.; Gràcia, I.; Horrillo, M.D.C. Portable Low-Cost Electronic Nose Based on Surface Acoustic Wave Sensors for the Detection of BTX Vapors in Air. Sensors 2019, 19, 5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.C.; Kadri, C.; Zhang, L.; Feng, J.W.; Juan, L.H.; Na, P.L. A Novel Cost-Effective Portable Electronic Nose for Indoor-/In-Car Air Quality Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Computer Distributed Control and Intelligent Environmental Monitoring, Zhangjiajie, China, 5–6 March 2012; pp. 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Tian, F.; Hu, B.; Ye, Q.; Xiao, B.; Guo, J. On-Line Drift Reduction for Portable Electronic Nose Instrument in Monitoring Indoor Formaldehyde. In Proceedings of the 2012 12th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 17–21 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, M.M.; Seok, C.; Wu, X.; Sennik, E.; Biliroglu, A.O.; Adelegan, O.J.; Kim, I.; Jur, J.S.; Yamaner, F.Y.; Oralkan, O. A Low-Power Wearable E-Nose System Based on a Capacitive Micromachined Ultrasonic Transducer (CMUT) Array for Indoor VOC Monitoring. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 19684–19696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, T.; Koyama, Y.; Shin, W.; Akamatsu, T.; Tsuruta, A.; Masuda, Y.; Uchiyama, K. Selective Detection of Target Volatile Organic Compounds in Contaminated Air Using Sensor Array with Machine Learning: Aging Notes and Mold Smells in Simulated Automobile Interior Contaminant Gases. Sensors 2020, 20, 2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Huo, D.; Zhang, J. Gas Recognition in E-Nose System: A Review. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2022, 16, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.-I.; Chang, K.-H.; Jhang, J.-Y.; Chiu, S.-W.; Wang, G.; Yang, C.-H.; Chiueh, H.; Chen, H.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Chang, M.-F.; et al. A 1-V 2.6-mW Environmental Compensated Fully Integrated Nose-on-a-Chip. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2018, 65, 1365–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-C.; Rabaey, J.M. A Bio-Inspired Analog Gas Sensing Front End. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Regul. Pap. 2017, 64, 2611–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Meng, Q.-H.; Lilienthal, A.J.; Qi, P.-F. Development of Compact Electronic Noses: A Review. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2021, 32, 062002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covington, J.A.; Marco, S.; Persaud, K.C.; Schiffman, S.S.; Nagle, H.T. Artificial Olfaction in the 21st Century. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 12969–12990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, R.; Yuan, X.; Chang, H. AI-driven Photonic Noses: From Conventional Sensors to Cloud-to-Edge Intelligent Microsystems. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2025, 11, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Saha, P.; Patro, S.K. Vibration-Based Damage Detection Techniques Used for Health Monitoring of Structures: A Review. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2016, 6, 477–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solà-Penafiel, N.; Manyosa, X.; Navarrete, E.; Ramos-Castro, J.; Jiménez, V.; Bermejo, S.; Gracia, I.; Llobet, E.; Domínguez-Pumar, M. Acceleration and Drift Reduction of MOX Gas Sensors Using Active Sigma-Delta Controls Based on Dielectric Excitation. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 365, 131940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AG, S. SGP41-VOC and NOx Sensor for Indoor Air Quality Applications. Available online: https://sensirion.com/products/catalog/SGP41 (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Gas Sensor BME688. Available online: https://www.bosch-sensortec.com/products/environmental-sensors/gas-sensors/bme688/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Kadhim, I.H.; Hassan, H.A.; Abdullah, Q.N. Hydrogen Gas Sensor Based on Nanocrystalline SnO2 Thin Film Grown on Bare Si Substrates. Nano-Micro Lett. 2016, 8, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3M Innovative Properties Co. Vehicle Cabin Air Filter Monitoring System. U.S. Patent Application 2023/0256373 A1, 17 August 2023.

- Fu, L.; You, S.; Li, G.; Fan, Z. Enhancing Methane Sensing with NDIR Technology: Current Trends and Future Prospects. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2023, 42, 20230062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesinghe, D.R.; Zobair, M.A.; Esmaeelpour, M. A Review on Photoacoustic Spectroscopy Techniques for Gas Sensing. Sensors 2024, 24, 6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho Rezende, G.; Le Calvé, S.; Brandner, J.J.; Newport, D. Micro Photoionization Detectors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 287, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankins, J.C. Technology Readiness Assessments: A Retrospective. Acta Astronaut. 2009, 65, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 26262; Road vehicles—Functional safety. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

| Year | Title and Authors | Type | CMOS-MEMS Integration | Commercial Comparisons | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | Odor evaluation of vehicle interior materials based on portable E-nose (Sun et al.) | Research paper | Not covered | Not covered | [21] |

| 2022 | Development Trend of E-nose Technology in Closed Cabins Gas Detection: A Review (Tan et al.) | Review | Partial (MEMS mentioned) | Not covered | [8] |

| 2024 | E-nose for Gas Sensing Applications in Autonomous Vehicles (Raj et al.) | Conference paper | Not covered | Partial | [22] |

| 2025 | Modern Trends in the Application of E-nose Systems: A Review (Ivanov et al.) | Review | Partial (general trends) | Partial | [23] |

| 2025 | This paper | Review | Integration of CMOS-MEMS process with E-nose | Comparison between commercial vehicle sensors | - |

| Target | Film Thickness (nm) | Gas (ppm) | Power Consumption (mW) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn | - | NO2 (5–200) | - | [45] |

| SnO2, Pt-doped SnO2 | 50/120 | CO (25) C7H8 (25) CH2O (1) | 24.5–45 (300–440 °C) | [46] |

| The mixture of TiO2 and Al | - | CO (100–250) | - | [47] |

| W, Pd | 300 (WO3) 5–6 (Pd) | NO (1–50) | - | [48] |

| Method | Cost Level | Scalability | Temperature (°C) | Compatibility with MEMS | Key Advantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVD (Sputtering) | High | Good | RT-600 | Good | High purity | [54,55] |

| CVD | Medium | Good | >500 | Limited (thermal stress) | Excellent uniformity | [55] |

| Inkjet printing | Low | Excellent | RT-200 | Excellent | Mask-less | [58] |

| Sol–Gel | Low | Good | <200 | Good | Porous structures | [59] |

| Hydrothermal synthesis | Low | Excellent | <100 | Good | Hierarchical nanostructures | [60] |

| Low-Temp ALD | High | Excellent | RT-300 | Superior | Conformal coverage in 3D structures | [61] |

| Materials | Processing | Mechanical Compatibility | Temperature (°C) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon | Deep Reactive Ion Etching | Rigid and Brittle | >1000 | [84] |

| Glass | Laser Drilling | Rigid/Insulating | ~500–850 | [85] |

| Alumina | Tape Casting/Sintering | Rigid/Hard | >1500 | [86] |

| Polyimide | Spin Coating/Laser Cutting | Flexible/Conformal | <400 | [86] |

| Gas | Algorithm/Model | Recognition Accuracy (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO, CH4 and NO2 | Momentum Back-Propagation Algorithm | - | [109] |

| 6 VOCs (including CH2O, CH3COCH3) | The integrated model based on ELM-ELM structure | 99% (training), 93% (testing) | [110] |

| CH2O (in various mixed gases) | ELM | 100% | [111] |

| Four gas sources | Spatio-temporal Cross-attention Gas identification Algorithm | 99.6% (training), 99.2% (testing) | [112] |

| CO, CH4, C3H8 (50, 80, 100 ppm) | Convolutional Long Short-Term Neural Network | 96.76% (Overall Recognition Rate) | [113] |

| 9 different essential oils (volatile gases) | 1D-CNN | 97.76% | [114] |

| Sensor Type/Material | Target Gases | Detection Range | Response Time (s) | Power Consumption | Estimated Lifetime/Stability | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bosch BME688 | VOCs, VSCs, CO2, H2 | ppb level | 0.75–92 (depending on the mode) | <0.1 mA in ultra-low power mode | Long-term stability | [149] |

| Sensirion SGP41 | VOCs, NOx | ppb level | <10 (C2H5OH, from 5000 to 10,000 ppb) | <15 mW (Measurement Mode) | 10 years (tested in a simulated indoor environment) | [148] |

| Pd/SnO2 | H2 | 150–1000 ppm | 182 (75 °C) | 65/86 μW (two devices) | - | [150] |

| Au/ZnO (nanofibers) | NO2 | 0.125–5 ppm | 2300 (red LED) | <10 mW | >30 days (blue LED irradiation) | [81] |

| Pd/CeO2 (nanofibers) | CH4O | 5 ppm (limit of detection) | 1 | <10 mW (MEMS) | - | [78] |

| Supplier | Sensor | Detected Parameters | Power Consumption | Key Features | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensirion AG, Stäfa, Switzerland | SGP41 | VOCs, NOx | <15 mW (Measurement Mode) | high stability, portability | [148] |

| Bosch Sensortec GmbH, Reutlingen, Germany | BME688 | VOCs, VSCs | <0.1 mA in ultra-low power mode | AI-integrated, low power consumption | [149] |

| Vehicle cabin air filter monitoring system | Electrochemical sensor | NOx, NH3 | - | Cabin monitoring patents | [151] |

| Technology | Principle | Sensitivity | Power | Commercial Maturity | Suitability for Multi-Gas E-Nose | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOX MEMS sensors | Resistive | ppb level (temperature dependence) | Low power consumption | While commercial use has been achieved, there is still room for improvement in cost reduction. | Can be combined with temperature and humidity sensors easily | [87] |

| NDIR | Infrared absorption | ppm level (light source impact) | Affected by the light source | A highly effective and commonly used method. | Optical E-nose system based on NDIR sensors | [152] |

| Photoacoustic Spectroscopy | Acoustic detection | ppb level | Directly proportional to the incident light power | The overall system cost remains high. | Suitable (utilizing tunable lasers) | [153] |

| PID | UV ionization | ppb level | mW level (e.g., 1.4 mW for μDPID) | The existing portable PIDs are already small (20 mm) and lightweight (8 g) | Suitable (low power consumption) | [154] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lin, X.; Tan, R.; Shen, W.; Lv, D.; Song, W. In-Vehicle Gas Sensing and Monitoring Using Electronic Noses Based on Metal Oxide Semiconductor MEMS Sensor Arrays: A Critical Review. Chemosensors 2026, 14, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010016

Lin X, Tan R, Shen W, Lv D, Song W. In-Vehicle Gas Sensing and Monitoring Using Electronic Noses Based on Metal Oxide Semiconductor MEMS Sensor Arrays: A Critical Review. Chemosensors. 2026; 14(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Xu, Ruiqin Tan, Wenfeng Shen, Dawu Lv, and Weijie Song. 2026. "In-Vehicle Gas Sensing and Monitoring Using Electronic Noses Based on Metal Oxide Semiconductor MEMS Sensor Arrays: A Critical Review" Chemosensors 14, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010016

APA StyleLin, X., Tan, R., Shen, W., Lv, D., & Song, W. (2026). In-Vehicle Gas Sensing and Monitoring Using Electronic Noses Based on Metal Oxide Semiconductor MEMS Sensor Arrays: A Critical Review. Chemosensors, 14(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010016