Benzoxazole Iminocoumarins as Multifunctional Heterocycles with Optical pH-Sensing and Biological Properties: Experimental, Spectroscopic and Computational Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Part

2.1. Chemistry

2.1.1. General Methods

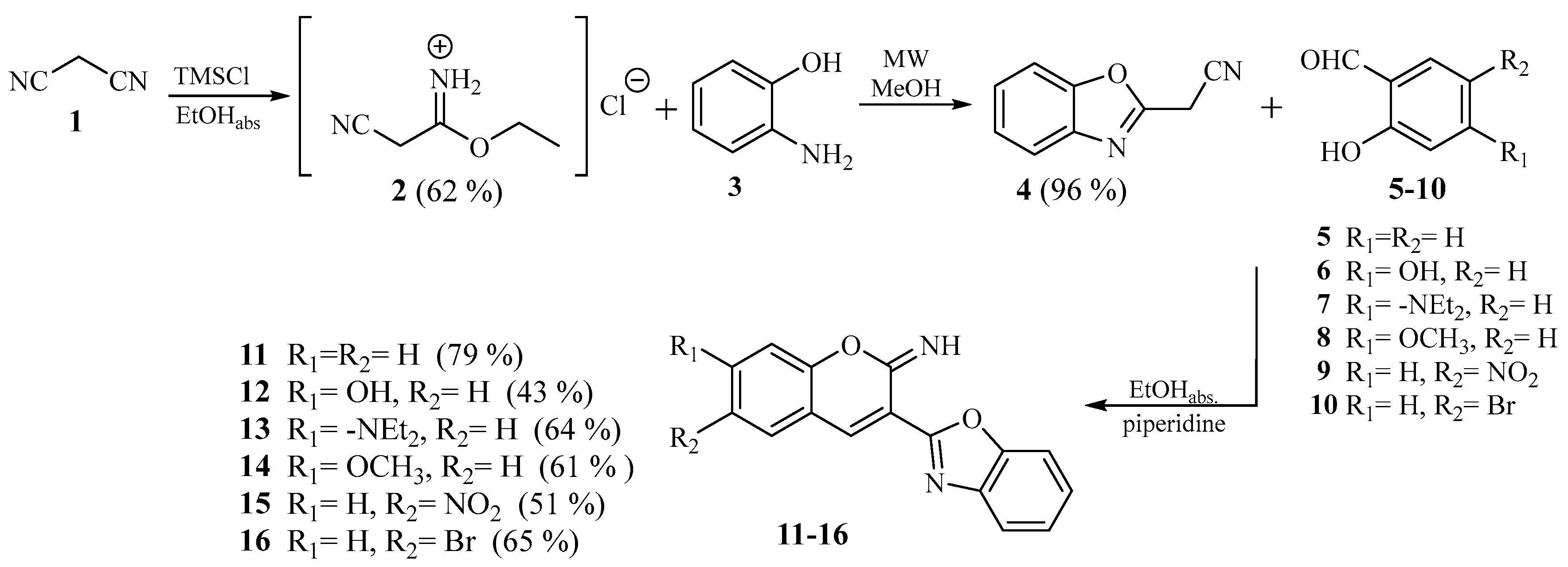

2.1.2. General Method for Preparation of Compounds 11–16

2.2. Spectroscopic Characterization

2.3. pH Titrations

2.4. NMR Spectroscopy Analysis Under Varying pH Conditions

2.5. Computational Details

2.6. Biological Activity

2.6.1. Antiproliferative Activity In Vitro

2.6.2. Antiviral Activity In Vitro

2.6.3. Antifungal Activity In Vitro

3. Results and Discussion

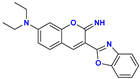

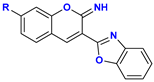

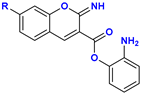

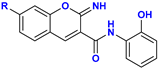

3.1. Chemistry

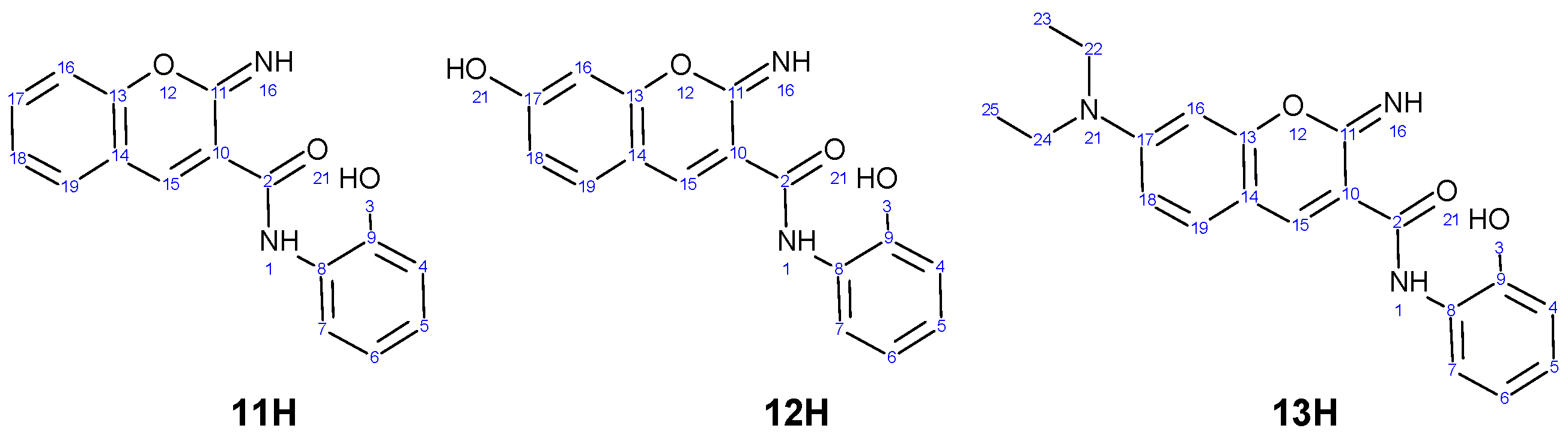

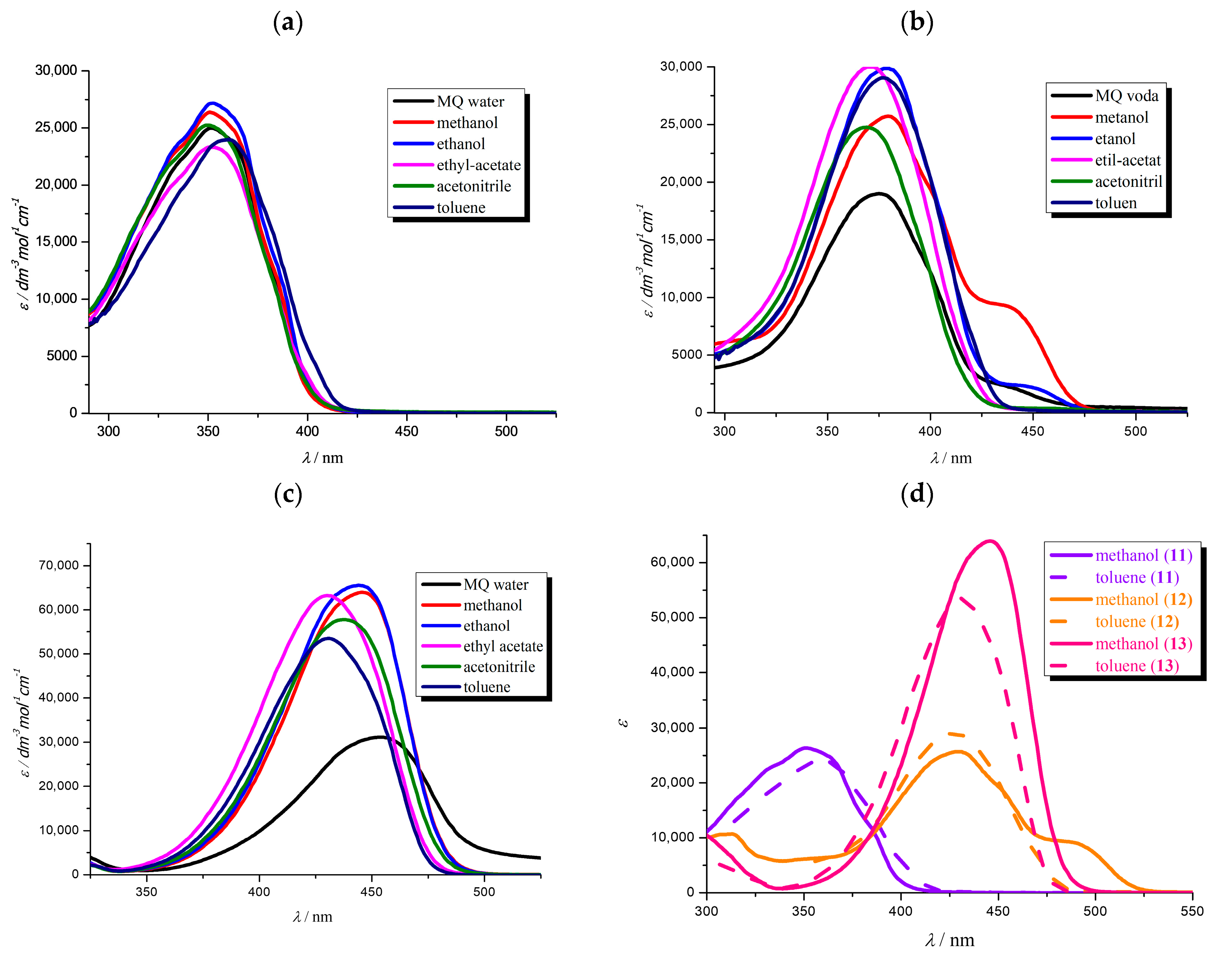

3.2. Spectroscopic Characterization

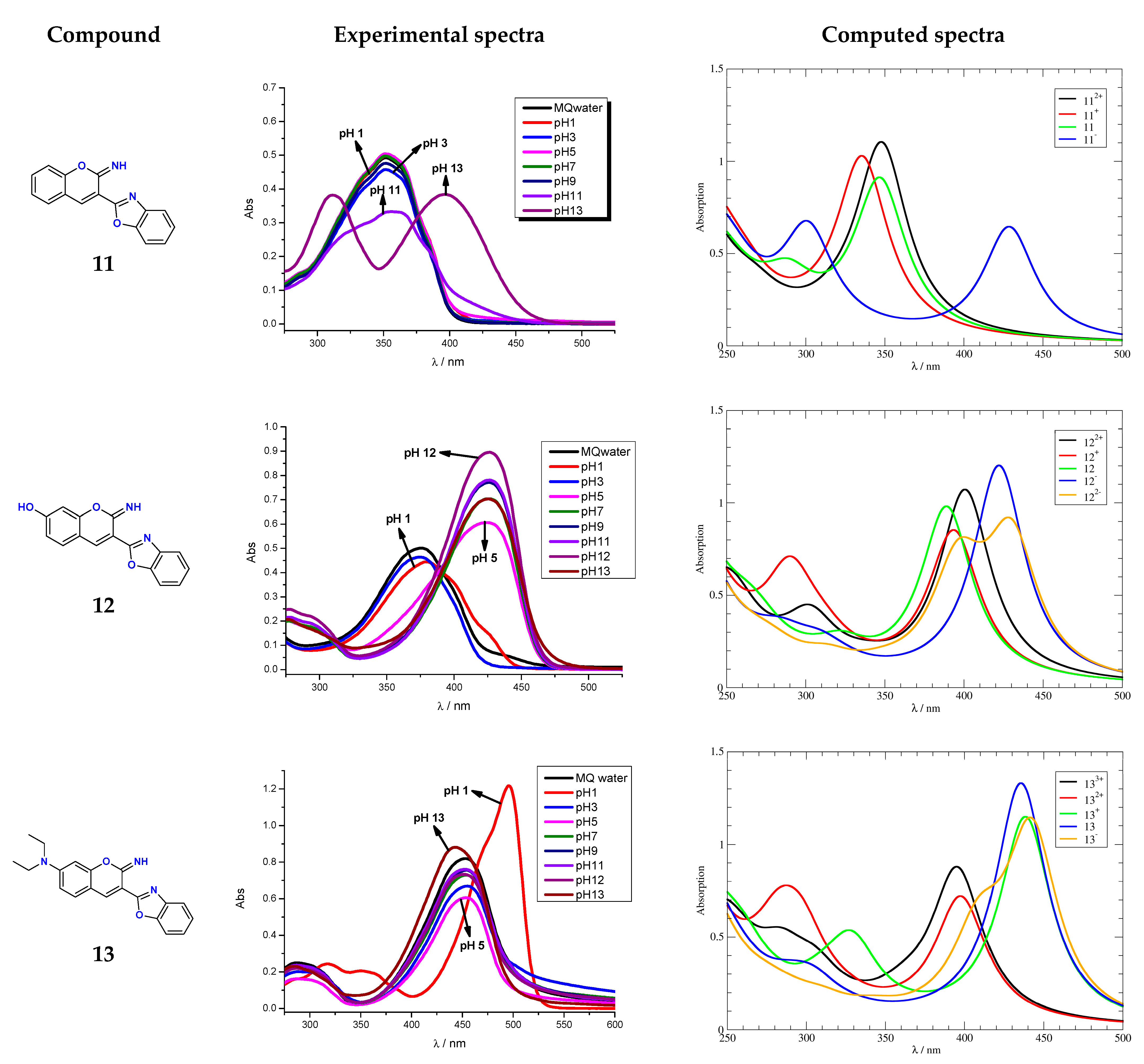

3.3. Effects of pH on Spectral Properties

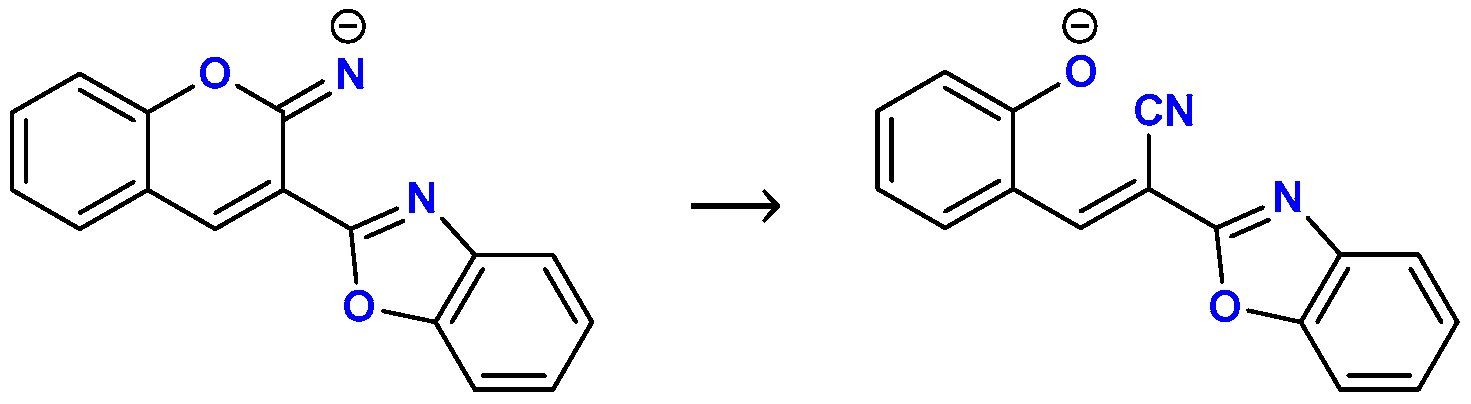

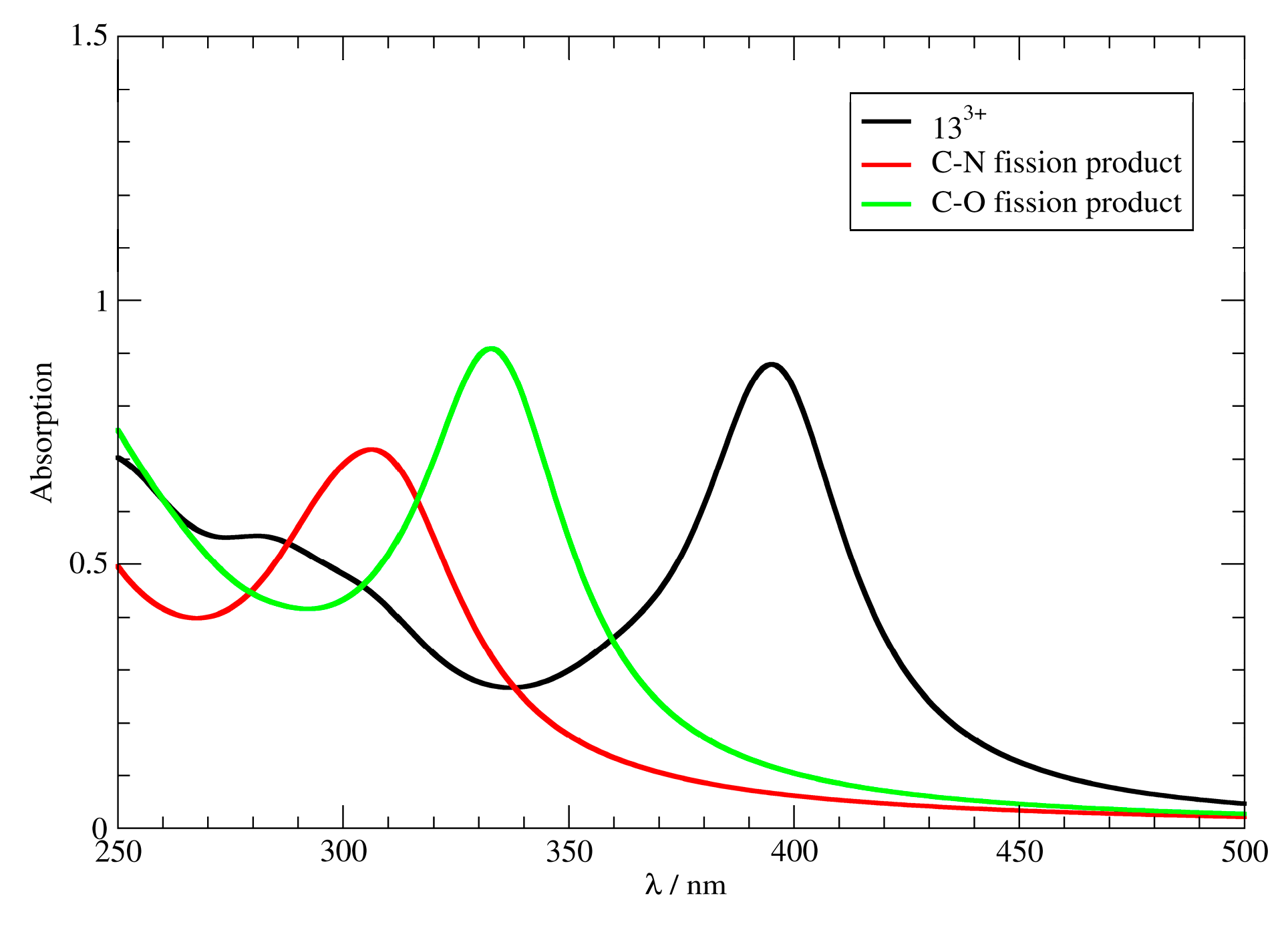

3.4. Computational Analysis

3.5. Probing the Protonation Equilibria with NMR Spectroscopy

3.6. Multifunctional Potential: Preliminary Biological Evaluation

3.6.1. Antiproliferative Activity In Vitro

3.6.2. Antiviral Activity In Vitro

3.6.3. Antifungal Activity In Vitro

3.6.4. Comparison with Literature Systems

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hussain, M.K.; Khatoon, S.; Khan, M.F.; Akhtar, M.S.; Ahamad, S.; Saquib, M. Coumarins as Versatile Therapeutic Phytomolecules: A Systematic Review. Phytomedicine 2024, 134, 155972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanachi, A.; Leonetti, F.; Pisani, L.; Catto, M.; Carotti, A. Coumarin: A Natural, Privileged and Versatile Scaffold for Bioactive Compounds. Molecules 2018, 23, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinegger, A.; Wolfbeis, O.S.; Borisov, S.M. Optical Sensing and Imaging of pH Values: Spectroscopies, Materials, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 12357–12489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureš, F. Fundamental aspects of property tuning in push–pull molecules. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 58826–58851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udhayakumari, D.; Ramasundaram, S.; Jerome, P.; Oh, T.H. A Review on Small Molecule Based Fluorescence Chemosensors for Bioimaging Applications. J. Fluoresc. 2025, 35, 3763–3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y. Recent Advances in Excimer-Based Fluorescence Probes for Biological Applications. Molecules 2022, 27, 8628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfbeis, O.S.; Fürlinger, E.; Kroneis, H.; Marsoner, H. A Study on Fluorescent Indicators for Measuring Near-Neutral (“Physiological”) pH Values. Fresenius J. Anal. Chem. 1983, 314, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfbeis, O.S.; Koller, E.; Hochmuth, P. Electronic Spectra and Dissociation Constants of 3-Substituted 7-Hydroxycoumarins. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1985, 58, 731–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, P.; Tarraga, A.; Oton, F. Imidazole Derivatives: A Comprehensive Survey of Their Recognition Properties. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 1711–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasylevska, A.S.; Karasyov, A.A.; Borisov, S.M.; Klimant, I. Novel coumarin-based fluorescent pH indicators, probes and membranes covering a broad pH range. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 387, 2131–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Sarkar, S.; Nandy, M.; Ahn, K.H. Imidazolyl-benzocoumarins as ratiometric fluorescence probes for biologically extreme acidity. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 248, 119088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achelle, S.; Rodríguez-López, J.; Bureš, F.; Robin-le Guen, F. Tuning the Photophysical Properties of Push-Pull Azaheterocyclic Chromophores by Protonation: A Brief Overview of a French-Spanish-Czech Project. Chem. Rec. 2020, 20, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwaczko, K.; Kulkowska, A.; Matwijczuk, A. Advances in Coumarin Fluorescent Probes for Medical Diagnostics: A Review of Recent Developments. Biosensors 2026, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klikar, M.; Solanke, P.; Tydlitat, J.; Bureš, F. Alphabet-Inspired Design of (Hetero)Aromatic Push-Pull Chromophores. Chem. Rec. 2016, 16, 1886–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwat, A.A.; Avhad, K.C.; Patil, D.S.; Nagaiyan, S. Design and Synthesis of Coumarin-Imidazole Hybrid Chromophores: Solvatochromism, Acidochromism and Non-Linear Optical Properties. Photochem. Photobiol. 2019, 95, 740–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avhad, K.C.; Patil, D.S.; Gawale, Y.K.C.; Sreenath, M.C.S.; Joe, I.H.; Sekar, N. Large Stokes Shifted Far-Red to NIR-Emitting D-π-A Coumarins: Combined Synthesis, Experimental, and Computational Investigation of Spectroscopic and Non-Linear Optical Properties. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 4393–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boček, I.; Hranjec, M.; Vianello, R. Imidazo [4,5-b]pyridine Derived Iminocoumarins as Potential pH Probes: Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Computational Studies of Their Protonation Equilibria. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 355, 118982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Xuan, Q.P.; Moon, H.; Jun, Y.W.; Ahn, K.H. Synthesis of Benzocoumarins and Characterization of Their Photophysical Properties. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2014, 3, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Sarkar, S.; Song, C.W.; Reo, Y.J.; Yang, Y.J.; Ahn, K.H. Bent-Benzocoumarin Dyes That Fluoresce in Solution and in Solid State and Their Application to Bioimaging. ChemPhotoChem 2020, 4, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zheng, M.; Jia, J.; Wang, W.; Cui, Y.; Gao, J. New coumarin-benzoxazole derivatives: Synthesis, photophysical and NLO properties. Dye. Pigment. 2019, 166, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zheng, H.; Liu, G.; Wang, P.; Xiang, R. Synthesis and Application of a Multifunctional Fluorescent Polymer Based on Coumarin. BioResources 2016, 11, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zheng, H.; Guo, M.; Du, L.; Liu, G.; Wang, P. Synthesis of Polymeric Fluorescent Brightener Based on Coumarin and Its Performances on Paper as Light Stabilizer, Fluorescent Brightener and Surface Sizing Agent. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 367, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlodarczyk, P.; Komarneni, S.; Roy, R.; White, W.B. Enhanced Fluorescence of Coumarin Laser Dye in the Restricted Geometry of a Porous Nanocomposite. J. Mater. Chem. 1996, 6, 1967–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-de-Armas, R.; San Miguel, M.Á.; Oviedo, J.; Sanz, J.F. Coumarin Derivatives for Dye Sensitized Solar Cells: A TD-DFT Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, B.D. The Use of Coumarins as Environmentally-Sensitive Fluorescent Probes of Heterogeneous Inclusion Systems. Molecules 2009, 14, 210–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Bu, Y.; Wang, J.; Qu, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X.; Liu, G.; Wu, Z.; Chen, G.; Zhou, H. A Convenient Fluorescent Probe for Monitoring Lysosomal pH Change and Imaging Mitophagy in Living Cells. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 330, 129333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, M.; Kuroda, D.; Watanabe, K.; Miyoshi, N. Application of 2-(3,5,6-trifluoro-2-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)benzoxazole and -benzothiazole to fluorescent probes sensing pH and metal cations. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 7328–7333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beč, A.; Vianello, R.; Hranjec, M. Synthesis and Spectroscopic Characterization of Multifunctional D-π-A Benzimidazole Derivatives as Potential pH Sensors. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 386, 122493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowska, A.; Sączewski, F.; Bednarski, P.J.; Gdaniec, M.; Balewski, Ł.; Warmbier, M.; Kornicka, A. Synthesis, Structure and Cytotoxic Properties of Copper(II) Complexes of 2-Iminocoumarins Bearing a 1,3,5-Triazine or Benzoxazole/Benzothiazole Moiety. Molecules 2022, 27, 7155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowska, A.; Wolff, L.; Sączewski, F.; Bednarski, P.J.; Kornicka, A. Synthesis and Cytotoxic Evaluation of Benzoxazole/Benzothiazole-2-Imino-Coumarin Hybrids and Their Coumarin Analogues as Potential Anticancer Agents. Pharmazie 2019, 74, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ammar, H.; Kaddachi, M.T.; Kahn, P.H. Conversion of Malononitrile into 2-Cyanomethyl Compounds. Phys. Chem. News 2003, 9, 137–139. [Google Scholar]

- Perin, N.; Cindrić, M.; Vervaeke, P.; Liekens, S.; Mašek, T.; Starčević, K.; Hranjec, M. Benzazole Substituted Iminocoumarins as Potential Antioxidants with Antiproliferative Activity. Med. Chem. 2021, 17, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursch, M.; Krossing, I.; Grimme, S. Best-Practice DFT Protocols for Basic Molecular Computational Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202205735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandarić, T.; Vianello, R. Computational Insight into the Mechanism of the Irreversible Inhibition of Monoamine Oxidase Enzymes by the Antiparkinsonian Propargylamine Inhibitors Rasagiline and Selegiline. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 3532–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissandier, M.D.; Cowen, K.A.; Feng, W.Y.; Gundlach, E.; Cohen, M.H.; Earhart, A.D.; Coe, J.V.; Tuttle, T.R. The Proton’s Absolute Aqueous Enthalpy and Gibbs Free Energy of Solvation from Cluster-Ion Solvation Data. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 7787–7794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenich, A.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rastija, V.; Vrandečić, K.; Ćosić, J.; Majić, I.; Kanižai Šarić, G.; Agić, D.; Karnaš, M.; Lončarić, M.; Molnar, M. Biological Activities Related to Plant Protection and Environmental Effects of Coumarin Derivatives: QSAR and Molecular Docking Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristinsson, H. Synthese von Heterocyclen; IV1. Neuer Syntheseweg zur Herstellung von Heterocyclischen Nitrilen. Synthesis 1979, 1979, 102–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, M.; Nozaka, P.A.; Shimamoto, M.; Ozaki, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Yoshioka, S.; Nagano, M.; Okamura, K.; Dateb, T.; Tamura, O. Synthesis of 2-Substituted Benzoxazoles. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1995, 13, 1759–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Xu, J.; Xu, M.; Bai, S.-P. Anti-Oligomerization Sheet Molecules: Design, Synthesis and Evaluation of Inhibitory Activities against α-Synuclein Aggregation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2019, 27, 3089–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, F.T.; Jeevanandam, A. Simple Transformation of Nitrile into Ester by the Use of Chlorotrimethylsilane. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 9455–9456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyani, H.; Daroonkala, M.D. A Cost-Effective and Green Aqueous Synthesis of 3-Substituted Coumarins Catalyzed by Potassium Phthalimide. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop. 2015, 29, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, C.; Welton, T. Solvents and Solvent Effects in Organic Chemistry, 4th ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonjo, T.; Futami, Y.; Morisawa, Y.; Wojcik, M.J.; Ozaki, Y. Hydrogen Bonding Effects on the Wavenumbers and Absorption Intensities of the OH Fundamental and the First, Second, and Third Overtones of Phenol and 2,6-Dihalogenated Phenols Studied by Visible/Near-Infrared/Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 9845–9853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, C.; Liu, Y. Effects of Solvent Polarity and Hydrogen Bonding on Coumarin 500. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 218, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Anslyn, E.V. Chemosensors: Principles, Strategies and Applications; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demchenko, A.P. Introduction to Fluorescence Sensing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshepelevitsh, S.; Kütt, A.; Lõkov, M.; Kaljurand, I.; Saame, J.; Heering, A.; Plieger, P.; Vianello, R.; Leito, I. On the Basicity of Organic Bases in Different Media. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 2019, 6735–6748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lõkov, M.; Tshepelevitsh, S.; Heering, A.; Plieger, P.G.; Vianello, R.; Leito, I. On the Basicity of Conjugated Nitrogen Heterocycles in Different Media. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2017, 4475–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yang, Z.; Yan, J.; Xue, Q. Direct Arylation of Benzoxazoles with Benzoyl Chlorides under Mild Conditions. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 27, e202400303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benassi, R.; Grandi, R.; Pagnoni, U.M.; Taddei, F. Study of the Effect of N-Protonation and N-Methylation on the 1H and 13C Chemical Shifts of the Six-Membered Ring in Benzazoles and 2-Substituted N,N-Dimethylamino Derivatives. Magn. Reson. Chem. 1986, 24, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P.F.; Morgan, K.J.; Turner, A.M. Studies in Heterocyclic Chemistry. Part IV. Kinetics and Mechanisms for the Hydrolysis of Benzoxazoles. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1972, 1582–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, G.A.; Rice, K.; Snyder, C.R. Ballistic Fibers: A Review of the Thermal, Ultraviolet and Hydrolytic Stability of the Benzoxazole Ring Structure. J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 41, 4105–4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherm, B.; Balmas, V.; Spanu, F.; Pani, G.; Delogu, G.; Pasquali, M.; Migheli, Q. The Wheat Pathogen Fusarium culmorum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2013, 14, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, M.D.; Thomma, B.P.; Nelson, B.D. Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary: Biology and Molecular Traits of a Cosmopolitan Pathogen. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2006, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, N.; Giachero, M.L.; Declerck, S.; Ducasse, D.A. Macrophomina phaseolina: General Characteristics of Pathogenicity and Methods of Control. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 634397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Aziem, A.; Baaiu, B.S.; Abdelhamid, A.O. Synthesis and Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity of Some Novel Heterocyclic Compounds from 5-Bromosalicylaldehyde. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2017, 54, 3471–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Peng, W.; Wang, D.; Hao, S.-H.; Li, W.-W.; Ding, F. Design, Synthesis, Antifungal Activity, and 3D-QSAR of Coumarin Derivatives. J. Pestic. Sci. 2018, 43, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Araújo, R.S.; Guerra, F.Q.; de O. Lima, E.; De Simone, C.A.; Tavares, J.F.; Scotti, L.; Scotti, M.T.; De Aquino, T.M.; De Moura, R.O.; Mendonça, F.J.B.; et al. Synthesis, Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR) and In Silico Studies of Coumarin Derivatives with Antifungal Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 1293–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkar, S.; Tahlan, S.; Lim, S.M.; Ramasamy, K.; Mani, V.; Shah, S.A.A.; Narasimhan, B. Benzoxazole derivatives: Design, synthesis and biological evaluation. Chem. Cent. J. 2018, 12, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes-Aguilar, A.; Merino-Montiel, P.; Montiel-Smith, S.; Meza-Reyes, S.; Vega-Báez, J.L.; Puerta, A.; Fernandes, M.X.; Padrón, J.M.; Petreni, A.; Nocentini, A.; et al. 2-Aminobenzoxazole-appended coumarins as potent and selective inhibitors of tumour-associated carbonic anhydrases. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2022, 37, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| λa (nm) | ε × 103 (dm3 mol−1 cm−1) | pKa(exp) | pKa(calc) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acidic a | Neutral b | Basic c | Acidic | Neutral | Basic | |||

| 11 | 351 | 351 | 311 396 | 24.90 | 34.90 | 19.10 19.20 | 11.0 | 12.8 |

| 12 | 259 380 | 276 427 | 276 427 | 7.90 20.55 | 13.05 36.45 | 8.65 42.75 | 4.8 | 4.7 |

| 13 | 317 349 496 | 287 453 | 285 443 | 12.20 10.30 60.85 | 11.05 36.45 | 11.95 44.05 | 13.0 | 13.5 |

| Compound | Protonation Forms | Process | pKa,CALC | pKa,EXP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11+ ⟶ 112+ | benzoxazole N protonation | −1.4 | |

| 11 ⟶ 11+ | iminocoumarin N protonation | 4.1 | ||

| 11 ⟶ 11− | iminocoumarin N deprotonation | 12.8 | 11.0 | |

| 12+ ⟶ 122+ | benzoxazole N protonation | −1.3 | |

| 12 ⟶ 12+ | iminocoumarin N protonation | 4.7 | 4.8 | |

| 12 ⟶ 12− | –OH deprotonation | 10.4 | ||

| 12− ⟶ 122− | iminocoumarin N deprotonation | 13.2 | ||

| 132+ ⟶ 133+ | benzoxazole N protonation | 0.6 | |

| 13+ ⟶ 132+ | aniline N protonation | 2.7 | ||

| 13 ⟶ 13+ | iminocoumarin N protonation | 7.6 | ||

| 13 ⟶ 13− | iminocoumarin N deprotonation | 13.5 | 13.0 |

| Reactant | Product | Reaction Gibbs Free Energy (ΔGR) |

|---|---|---|

|  C–N Fission Product | 11.6 kcal mol−1 (11, R = –H) 12.0 kcal mol−1 (12, R = –OH) 10.2 kcal mol−1 (13, R = –NEt2) |

C–O Fission Product | 1.3 kcal mol−1 (11, R = –H) 1.7 kcal mol−1 (12, R = –OH) 0.4 kcal mol−1 (13, R = –NEt2) |

| IC50 (µM) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd | Cell Lines | ||||||||

| Capan-1 | HCT-116 | LN-229 | NCI-H460 | DND-41 | HL-60 | K-562 | Z-138 | PBMC | |

| 11 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 12 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 87.3 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 13 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.045 | 0.075 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| 14 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 15 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 42.2 | 45.6 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 16 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 70.7 | 73.0 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| ETO | 0.3 | 1.3 | 5.8 | 1.2 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 5.22 | 0.57 | >10 |

| NOC | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 5.22 | 0.57 | >1 |

| Cpd | % Growth Inhibition After 48 h | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. sclerotiorum | M. phaseolina | B. cinereal | F. culmorum | |

| 11 | 21.35 ± 3.56 | 18.46 ± 0.00 | 9.23 ± 5.22 | 4.47 ± 2.23 |

| 12 | / | 8.12 ± 2.95 | 17.53 ± 7.60 | 12.30 ± 5.17 |

| 15 | / | 30.28 ± 2.41 | 23.99 ± 6.74 | 4.47 ± 2.23 |

| 16 | / | 34.71 ± 1.71 | 49.82 ± 4.26 | 3.36 ± 2.65 |

| 14 | / | 33.97 ± 2.83 | 37.82 ± 7.61 | 8.95 ± 2.24 |

| 13 | / | 19.20 ± 3.72 | 2.77 ± 1.85 | 5.59 ± 2.58 |

| negative control | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| positive control | 93.00 ± 0.00 strobilurin | 88.00 ± 0.00 mancozeb | 84.00 ± 0.00 fenhexamid | 87.50 ± 0.00 strobilurin |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Galić, M.; Čikoš, A.; Persoons, L.; Daelemans, D.; Vrandečić, K.; Karnaš, M.; Hranjec, M.; Vianello, R. Benzoxazole Iminocoumarins as Multifunctional Heterocycles with Optical pH-Sensing and Biological Properties: Experimental, Spectroscopic and Computational Analysis. Chemosensors 2026, 14, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010015

Galić M, Čikoš A, Persoons L, Daelemans D, Vrandečić K, Karnaš M, Hranjec M, Vianello R. Benzoxazole Iminocoumarins as Multifunctional Heterocycles with Optical pH-Sensing and Biological Properties: Experimental, Spectroscopic and Computational Analysis. Chemosensors. 2026; 14(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalić, Marina, Ana Čikoš, Leentje Persoons, Dirk Daelemans, Karolina Vrandečić, Maja Karnaš, Marijana Hranjec, and Robert Vianello. 2026. "Benzoxazole Iminocoumarins as Multifunctional Heterocycles with Optical pH-Sensing and Biological Properties: Experimental, Spectroscopic and Computational Analysis" Chemosensors 14, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010015

APA StyleGalić, M., Čikoš, A., Persoons, L., Daelemans, D., Vrandečić, K., Karnaš, M., Hranjec, M., & Vianello, R. (2026). Benzoxazole Iminocoumarins as Multifunctional Heterocycles with Optical pH-Sensing and Biological Properties: Experimental, Spectroscopic and Computational Analysis. Chemosensors, 14(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors14010015