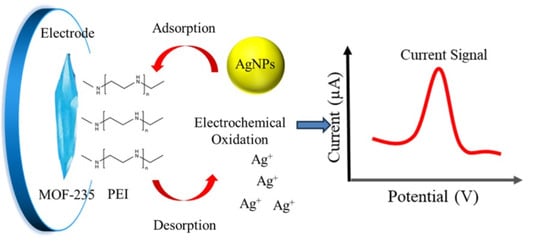

Polyethyleneimine-MOF-235 Composite-Enhanced Electrochemical Detection of Silver Nanoparticles in Cosmetics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Instruments and Reagents

2.2. Material Synthesis and Electrode Fabrication

2.3. Measurement and Sample Pretreatment

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Electrode Materials

3.2. Electrochemical Investigation and Characterization

3.3. Electrochemical Detection of AgNPs at PEI-MOF-235/GCE

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rafeeq, H.; Hussain, A.; Ambreen, A.; Zill-e-Huma; Waqas, M.; Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Functionalized nanoparticles and their environmental remediation potential: A review. J. Nanostruct. Chem. 2022, 12, 1007–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naganthran, A.; Verasoundarapandian, G.; Khalid, F.E.; Masarudin, M.J.; Zulkharnain, A.; Nawawi, N.M.; Karim, M.; Abdullah, C.M.C.; Ahmad, S.A. Synthesis, characterization and biomedical application of silver nanoparticles. Materials 2022, 15, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, P.; Kumar, V.; Singh, P.P.; Matharu, A.S.; Zhang, W.; Kim, K.-H.; Singh, J.; Rawat, M. Highly stable AgNPs prepared via a novel green approach for catalytic and photocatalytic removal of biological and non-biological pollutants. Environ. Int. 2020, 143, 105924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.K.; Yadav, S.; Dutta, S.; Kale, H.B.; Warkad, I.R.; Zbořil, R.; Varma, R.S.; Gawande, M.B. Silver nanomaterials: Synthesis and (electro/photo) catalytic applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 11293–11380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, G.V.; Madrid, A.T.; Gavilanes, A.F.; Naranjo, B.; Debut, A.; Arias, M.T.; Angulo, Y. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles for application in cosmetics. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2020, 55, 1304–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczepańska, E.; Bielicka-Giełdoń, A.; Niska, K.; Strankowska, J.; Żebrowska, J.; Inkielewicz-Stępniak, I.; Łubkowska, B.; Swebocki, T.; Skowron, P.; Grobelna, B. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles in context of their cytotoxicity, antibacterial activities, skin penetration and application in skincare products. Supramol. Chem. 2020, 32, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyene, H.D.; Werkneh, A.A.; Bezabh, H.K.; Ambaye, T.G. Synthesis paradigm and applications of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), a review. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2017, 13, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massarsky, A.; Trudeau, V.L.; Moon, T.W. Predicting the environmental impact of nanosilver. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2014, 38, 861–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondi, I.; Salopek-Sondi, B. Silver nanoparticles as antimicrobial agent: A case study on E. coli as a model for Gram-negative bacteria. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 275, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Shi, J.; Zou, X.; Wang, C.C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.W. Silver nanoparticles interact with the cell membrane and increase endothelial permeability by promoting VE-cadherin internalization. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 317, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Prajapati, P.; Boghra, R. Overview on application of nanoparticles in cosmetics. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2011, 1, 40–55. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, J.; Kan, W.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, S.W.; Wu, L.F.; Wang, J. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Eucommia ulmoides extract and their potential biological function in cosmetics. Heliyon 2022, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvioni, L.; Galbiati, E.; Collico, V.; Alessio, G.; Avvakumova, S.; Corsi, F.; Tortora, P.; Prosperi, D.; Colombo, M. Negatively charged silver nanoparticles with potent antibacterial activity and reduced toxicity for pharmaceutical preparations. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 2517–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Xie, H. Nanoparticles in daily life: Applications, toxicity and regulations. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2018, 37, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrano, D.M.; Barber, A.; Bednar, A.; Westerhoff, P.; Higginsd, C.P.; Ranville, J.F. Silver nanoparticle characterization using single particle ICP-MS (SP-ICP-MS) and asymmetrical flow field flow fractionation ICP-MS (AF4-ICP-MS). J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2012, 27, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Rigo, C.; Castillo-Michel, H.; Munivrana, I.; Vindigni, V.; Mičetić, I.; Benetti, F.; Manodori, L.; Cairns, W.R.L. Hydrodynamic chromatography coupled to single-particle ICP-MS for the simultaneous characterization of AgNPs and determination of dissolved Ag in plasma and blood of burn patients. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 5109–5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodeiro, P.; Achterberg, E.P.; Pampín, J.; Affatati, A.; El-Shahawi, M.S. Silver nanoparticles coated with natural polysaccharides as models to study AgNP aggregation kinetics using UV-Visible spectrophotometry upon discharge in complex environments. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 539, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Rees, N.V.; Compton, R. The electrochemical detection and characterization of silver nanoparticles in aqueous solution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, E.J.E.; Tschulik, K.; Omanović, D.; Cullen, J.T.; Jurkschat, K.; Crossley, A.; Compton, R.G. Electrochemical detection of commercial silver nanoparticles: Identification, sizing and detection in environmental media. Nanotechnology 2013, 24, 444002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Yue, R.; Huang, Y. Polyethylenimine-carbon nanotubes composite as an electrochemical sensing platform for silver nanoparticles. Talanta 2016, 160, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.I.; Duan, S.; Yue, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Xu, L.; Liu, Y.; Fang, M.; Yang, Q. High sensitive electrochemical detection of silver nanoparticles based on a MoS2/graphene composite. J. Nanopart. Res. 2022, 24, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansari, M.M.; Al-Dahmash, N.D.; Ranjitsingh, A.J.A. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using gum Arabic: Evaluation of its inhibitory action on Streptococcus mutans causing dental caries and endocarditis. J. Infect. Public Health. 2021, 14, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anbia, M.; Hoseini, V.; Sheykhi, S. Sorption of methane, hydrogen and carbon dioxide on metal-organic framework, iron terephthalate (MOF-235). J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2012, 18, 1149–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, E.; Jun, J.W.; Jhung, S.H. Adsorptive removal of methyl orange and methylene blue from aqueous solution with a metal-organic framework material, iron terephthalate (MOF-235). J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 185, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmer, D.B.; Han, L.; Lehmann, M.L.; Siddel, D.H.; Yang, G.; Chowdhury, A.U.; Doughty, B.; Elliott, A.M.; Saito, T. Additive manufacturing of strong silica sand structures enabled by polyethyleneimine binder. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.P.; Anson, F.C. Cyclic and differential pulse voltammetric behavior of reactants confined to the electrode surface. Anal. Chem. 1977, 49, 1589–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, L.C.D.; Santos, T.I.S.; Santos, J.E.L.; da Silva, D.R.; Martínez-Huitle, C.A. Metal organic framework-235 (MOF-235) modified carbon paste electrode for catechol determination in water. Electroanalysis 2021, 33, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepriá, G.; Córdova, W.R.; JiménezLamana, J.; Laborda, F.; Castillo, J.R. Silver nanoparticle detection and characterization in silver colloidal products using screen printed electrodes. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goda, T.; Ambrosi, A.; Miyahara, Y.; Pumera, M. Simultaneous Electrochemical Detection of Silver and Molybdenum Nanoparticles. ChemElectroChem 2014, 1, 529–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, V.R.; Hassan, P.A.; Haram, S.K. Size-dependent quantized double layer charging of monolayer-protected silver nanoparticles. New J. Chem. 2014, 38, 1761–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Batchelor-McAuley, C.; Compton, R.G. Silver nanoparticle detection in real-world environments via particle impact electrochemistry. ACS Sens. 2019, 4, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cepriá, G.; Pardo, J.; Lopez, A.; Peña, E.; Castillo, J.R. Selectivity of silver nanoparticle sensors: Discrimination between silver nanoparticles and Ag+. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 230, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, E.J.E.; Kristina, T.; Joanna, E.; Compton, R.G. Improving the Rate of Silver Nanoparticle Adhesion to ‘Sticky Electrodes’: Stick and Strip Experiments at a DMSA-Modified Gold Electrode. Electroanalysis 2014, 26, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, E.J.E.; Zhou, Y.G.; Rees, N.V.; Compton, R.G. Determining unknown concentrations of nanoparticles: The particle-impact electrochemistry of nickel and silver. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 6879–6884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Working Electrode | Peak Potential (Normalized vs. Ag/AgCl, V) | LOD (Normalized, g/L) | Linear Relationship (Normalized, ng/L) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macro-GCE | 0.42 | N/A | N/A | [19] |

| SPE | 0.31 | 5 × 10−7 | N/A | [28] |

| GCE | 0.24 | 3.31 × 10−8 | 33.1–500 | [29] |

| Pt disk electrode | 0.61 | N/A | N/A | [30] |

| Poly(amic) acid filter membrane electrode | 0.23 | 1.4 × 10−4 | N/A | [31] |

| GC microelectrode | 0.27 | 1 × 10−4 | 500–20,000 | [32] |

| DMSA/gold electrode | 0.37–0.51 | N/A | N/A | [33] |

| Carbon fiber microelectrode | 0.19 | N/A | N/A | [34] |

| MoS2-rGO/GCE | 0.27 | 2.63 × 10−9 | 5–120 | [21] |

| PEI-MOF-235/GCE | 0.26 | 3.93 × 10−9 | 10–100 | This work |

| Adding Mount (ng/L) | Electrochemical Detected Amount (ng/L) | Electrochemical Recovery (%) | ICP-MS Validation Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | - | - | |

| 10.0 | 9.83 ± 0.2 | 98.3 | 97.6 |

| 30.0 | 28.2 ± 0.3 | 94.0 | 95.9 |

| 50.0 | 49.7 ± 0.3 | 99.4 | 98.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duan, S.; Dai, H. Polyethyleneimine-MOF-235 Composite-Enhanced Electrochemical Detection of Silver Nanoparticles in Cosmetics. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13110392

Duan S, Dai H. Polyethyleneimine-MOF-235 Composite-Enhanced Electrochemical Detection of Silver Nanoparticles in Cosmetics. Chemosensors. 2025; 13(11):392. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13110392

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuan, Shuo, and Huang Dai. 2025. "Polyethyleneimine-MOF-235 Composite-Enhanced Electrochemical Detection of Silver Nanoparticles in Cosmetics" Chemosensors 13, no. 11: 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13110392

APA StyleDuan, S., & Dai, H. (2025). Polyethyleneimine-MOF-235 Composite-Enhanced Electrochemical Detection of Silver Nanoparticles in Cosmetics. Chemosensors, 13(11), 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13110392