Evaluation of an End-of-Life Essentials Online Education Module on Chronic Complex Illness End-of-Life Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- The impact of increased hospitalisation on people’s experiences and emotions in those living with chronic complex conditions.

- Clinical opportunities for end-of-life care along common disease trajectories in patients living with and dying from chronic complex conditions.

- The importance of ‘uncertainty’ in disease trajectories as a trigger in starting conversations in end-of-life care communication and in advance care planning.

- The potential for moral distress, self-care, and compassion associated with end-of-life care in a fast-paced environment.

- The opportunities for kindness and compassion in providing healthcare to people living with chronic complex disease.

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

2.2.1. Quantitative Data

- I have sufficient knowledge in providing end-of-life care;

- I am skilled in providing end-of-life care;

- I have a positive attitude towards end-of-life care;

- I am confident in my ability to provide good end-of-life care.

2.2.2. Qualitative Data

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

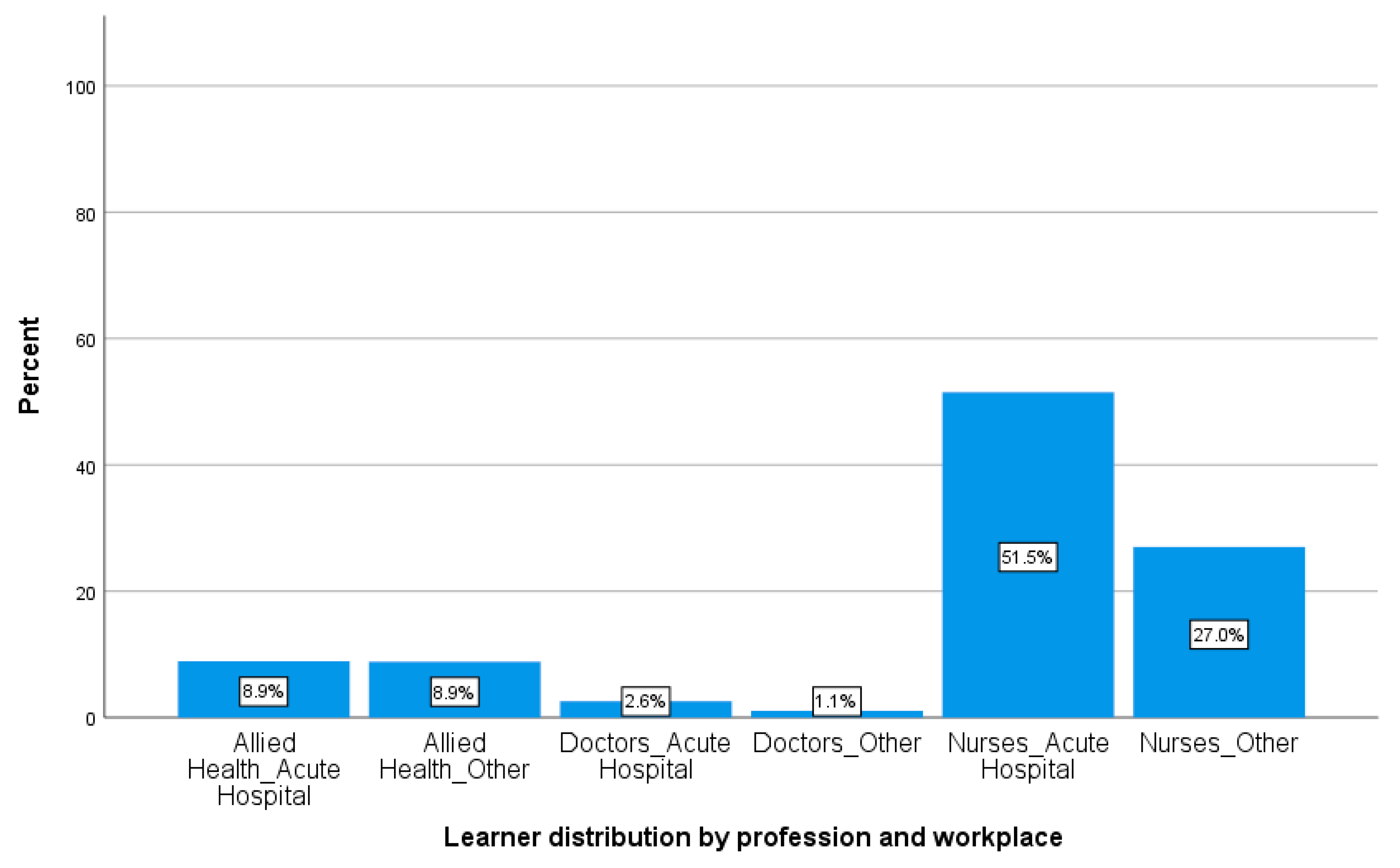

3.1.1. Demographics

3.1.2. Impact on Learners’ Knowledge, Skill, Attitude, and Confidence

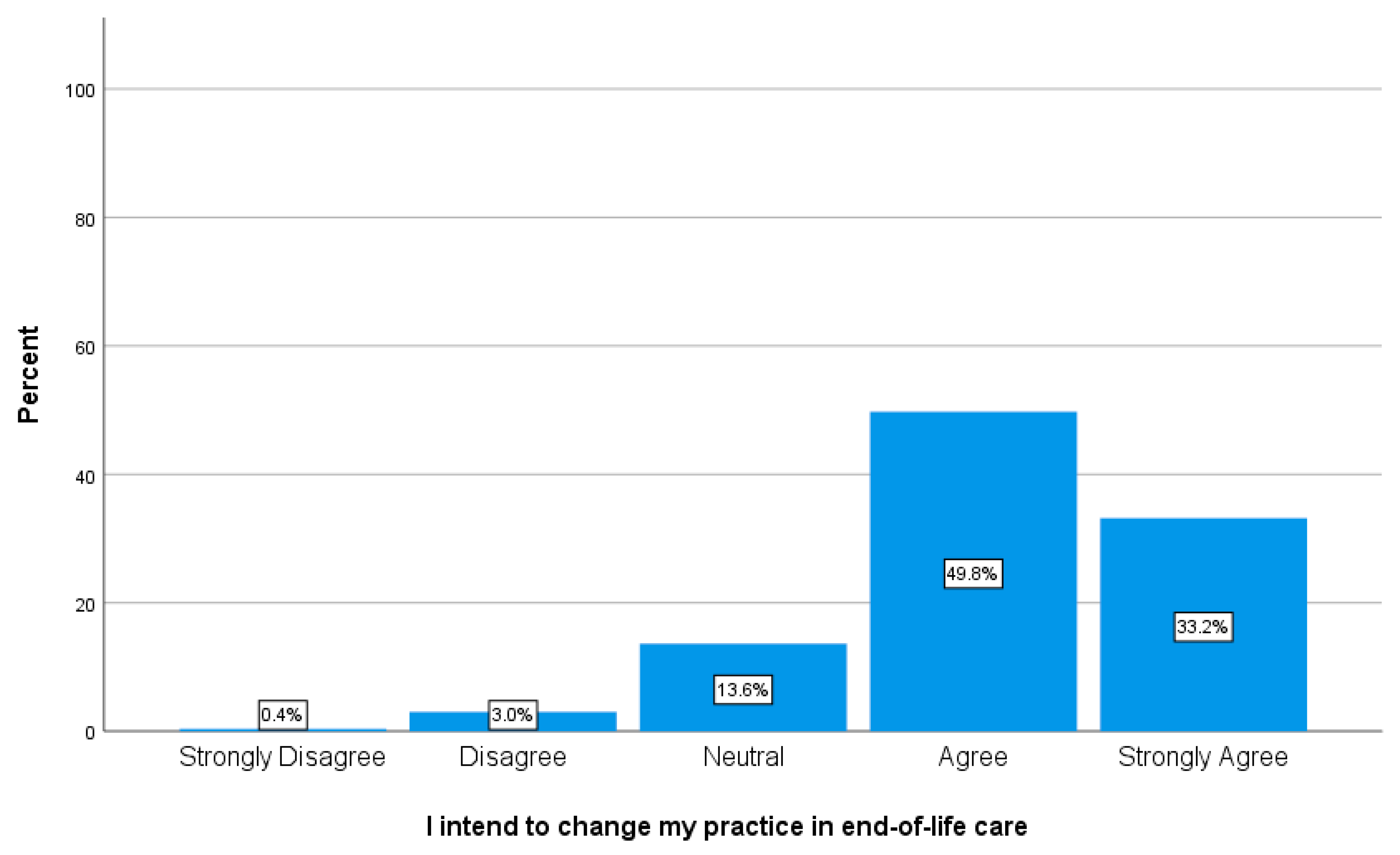

3.1.3. Intention to Change Clinical Practice

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.2.1. Patient-Centred Care and Care Planning

3.2.2. Discussion of Prognosis

3.2.3. Valued Communication Skills

4. Discussion

4.1. Patient-Centred Care

4.2. Acknowledging and Communicating Prognostic Uncertainty

4.3. The Importance of Skilled Communication

4.4. Implications for Future Research and Patient Care

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Deaths in Australia. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/life-expectancy-death/deaths-in-australia/contents/summary (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Jones, D.S.; Podolsky, S.H.; Greene, J.A. The burden of disease and the changing task of medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2333–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory, Top Ten Causes of Death. Available online: https://www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/causes_death/top_10/en/ (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Swerissen, H.; Duckett, S. Dying Well; Grattan Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Etkind, S.N.; Bristowe, K.; Bailey, K.; Selman, L.E.; Murtagh, F.E. How does uncertainty shape patient experience in advanced illness? A secondary analysis of qualitative data. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramling, R.; Stanek, S.; Han, P.K.J.; Duberstein, P.; Quill, T.E.; Temel, J.S.; Alexander, S.C.; Anderson, W.G.; Ladwig, S.; Norton, S.A. Distress Due to Prognostic Uncertainty in Palliative Care: Frequency, Distribution, and Outcomes among Hospitalized Patients with Advanced Cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, T.W.; Temel, J.S.; Helft, P.R. “How Much Time Do I Have?”: Communicating Prognosis in the Era of Exceptional Responders. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2018, 38, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National Consensus Statement: Essential Elements for Safe and High-Quality End-of-Life Care; ACSQHC: Sydney, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Productivity Commission. Introducing Competition and Informed User Choice into Human Services: Reforms to Human Services, Report No. 85; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brighton, L.J.; Bristowe, K. Communication in palliative care: Talking about the end of life, before the end of life. Postgrad. Med. J. 2016, 92, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Safety and Quality of End-of-Life Care in Acute Hospitals: A Background Paper; ACSQHC: Sydney, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings, D.; Devery, K.; Poole, N. Improving quality in hospital end-of-life care: Honest communication, compassion and empathy. BMJ Open Qual. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkind, S.N.; Koffman, J. Approaches to managing uncertainty in people with life-limiting conditions: Role of communication and palliative care. Postgrad. Med. J. 2016, 92, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngas, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Willis, K.; Hughes, E.; Small, R.; Welch, N.; Gibbs, L.; Daly, J. Generating best evidence from qualitative research: The role of data analysis. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2007, 31, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mays, N.; Pope, C. Qualitative Research: Rigour and qualitative research. BMJ 1995, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coimín, D.O.; Prizeman, G.; Korn, B.; Donnelly, S.; Hynes, G. Dying in acute hospitals: Voices of bereaved relatives. BMC Palliat. Care 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eccles, M.P.; Hrisos, S.; Francis, J.; Kaner, E.F.; Dickinson, H.O.; Beyer, F.; Johnston, M. Do self-reported intentions predict clinicians’ behaviour: A systematic review. Implem. Sci. 2006, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawlings, D.; Tieman, J.; Moores, C. E-learning: Who uses it and what difference does it make? Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2019, 25, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fix, G.M.; Van Deusen Lukas, C.; Bolton, R.E.; Hill, J.N.; Mueller, N.; LaVela, S.L.; Bokhour, B.G. Patient-centred care is a way of doing things: How healthcare employees conceptualize patient-centred care. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Patient-Centred Care: Improving Quality and Safety Through Partnerships with Patients and Consumers; ACSQHC: Sydney, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.J.; Bloch, S.; Armstrong, M.; Stone, P.C.; Low, J.T. Communication between healthcare professionals and relatives of patients approaching the end-of-life: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Palliat. Med. 2019, 33, 926–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluyas, H. Patient-centred care: Improving healthcare outcomes. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 30, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secunda, K.; Wirpsa, M.J.; Neely, K.J.; Szmuilowicz, E.; Wood, G.J.; Panozzo, E.; McGrath, J.; Levenson, A.; Peterson, J.; Gordon, E.J.; et al. Use and Meaning of “Goals of Care” in the Healthcare Literature: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Discourse Analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 35, 1559–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, K.P.; Ajayi, T.A. Do We Know What We Mean? An Examination of the Use of the Phrase “Goals of Care” in the Literature. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 22, 1546–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanning, J.; Walker, K.J.; Horrigan, D.; Levinson, M.; Mills, A. Review article: Goals-of-care discussions for adult patients nearing end of life in emergency departments: A systematic review. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2019, 31, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavazzi, A.; De Maria, R.; Manzoli, L.; Bocconcelli, P.; Di Leonardo, A.; Frigerio, M.; Gasparini, S.; Humar, F.; Perna, G.; Pozzi, R.; et al. Palliative needs for heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Results of a multicenter observational registry. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 184, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krawczyk, M.; Gallagher, R. Communicating prognostic uncertainty in potential end-of-life contexts: Experiences of family members. BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vliet, L.M.; Francke, A.L.; Meijers, M.C.; Westendorp, J.; Hoffstädt, H.; Evers, A.W.; van der Wall, E.; de Jong, P.; Peerdeman, K.J.; Stouthard, J.; et al. The Use of Expectancy and Empathy When Communicating With Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer; an Observational Study of Clinician–Patient Consultations. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grbich, C.; Parish, K.; Glaetzer, K.; Hegarty, M.; Hammond, L.; McHugh, A. Communication and decision making for patients with end stage diseases in an acute care setting. Contemp. Nurse 2006, 23, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virdun, C.; Luckett, T.; Davidson, P.M.; Phillips, J. Dying in the hospital setting: A systematic review of quantitative studies identifying the elements of end-of-life care that patients and their families rank as being most important. Palliat. Med. 2015, 29, 774–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, S.; Beamer, K.; Hack, T.F.; McClement, S.; Raffin Bouchal, S.; Chochinov, H.M.; Hagen, N.A. Sympathy, empathy, and compassion: A grounded theory study of palliative care patients’ understandings, experiences, and preferences. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, S.; Jordan, Z. The patient experience of patient-centered communication with nurses in the hospital setting: A qualitative systematic review protocol. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2015, 13, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavarski, D. A descriptive study of how nurses can engender hope. MEDSURG Nurs. 2018, 27, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Petley, R. How a model of communication can assist nurses to foster hope when communicating with patients living with a terminal prognosis. Religions 2017, 8, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattes, M.D.; Sloane, M.A. Reflections on Hope and Its Implications for End-of-Life Care. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 63, 993–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oosterveld-Vlug, M.G.; Francke, A.L.; Pasman, H.R.W.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D. How should realism and hope be combined in physician-patient communication at the end of life? An online focus-group study among participants with and without a Muslim background. Palliat. Support. Care 2016, 15, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, R.P.; Engelberg, R.A.; Back, A.L.; Ford, D.W.; Curtis, R. Internal medicine trainee self-assessments of End-of-Life communication skills do not predict assessments of patients, families, or clinician-evaluators. J. Palliat. Med. 2012, 15, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Statements | Pre-Evaluation Mean ± SD | Post-Evaluation Mean ± SD | Wilcoxon (Z) | p Value | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have sufficient knowledge in providing end-of-life care | 3.53 ± 0.95 | 4.03 ± 0.74 | −16.748 | <0.001 | −0.362 |

| I am skilled in providing end-of-life care | 3.50 ± 1.0 | 3.95 ± 0.79 | −15.573 | <0.001 | −0.339 |

| I have a positive attitude towards end-of-life care | 4.17 ± 0.75 | 4.36 ± 0.64 | −10.130 | <0.001 | −0.220 |

| I am confident in my ability to provide good end-of-life care | 3.76 ± 0.89 | 4.10 ± 0.73 | −13.993 | <0.001 | −0.304 |

| Subtheme | Description | No (%) Learners | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acknowledge the uncertainty and give information on prognosis | This pertains to providing the patient and family with accurate information on their current condition, illness, or disease trajectory, and seeking further clarification from other medical staff if required, in order to answer patient questions. HCP also acknowledged to the patient and family that there was some uncertainty about the patient’s disease progression and amount of time they may have left prior to death. They also discussed the possibility that patients are approaching their end of life. | 280 (50.1%) learner statements related to this subtheme. | “Admit we don’t know what the future may hold with your illness” “Acknowledge that dying is a possibility” “By including conversations regarding prognostic uncertainty, we can often alleviate some of the distress regarding end of life” “Discuss facts and diagnostic test results” |

| Determine what the patient wants to know | This pertains to the importance of HCP asking the patient and family how much information they want to be given about their illness and prognosis. Some patients may want to know more than others, but what is most important is establishing this at the outset. | 51 (9.1%) learner statements related to this subtheme. | “…the patient can still express preferences about the amount of knowledge they would like about what to expect in the course of their illness.” “Would they like more information about how the illness will most likely progress or not?” |

| Check patient’s understanding | This pertains to HCP asking the patient how much they currently know and understand about their medical condition, disease trajectory, and prognosis. | 31 (5.5%) learner statements related to this subtheme. | “It is important to simply ask the patient about their current condition and whether they understand the situation.” “consider the disease process and the patient and families understanding of that process.” |

| Subtheme | Description | No (%) Learners | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Honesty | This pertains to the importance of being honest and telling the truth, i.e., ensuring discussions around goals of care and prognostic uncertainty are done so with honesty on the part of the HCP. | 108 (19.3%) learner statements related to this subtheme. | “Always be honest with the patient” “Be honest and realist with them.” “Discussing all the possible outcomes very honestly.” |

| Being supportive | This pertains to providing support and reassurance to the patient and family (e.g., emotional support, taking the time to be with the patient), as well as being friendly, warm, and kind (e.g., through acts of kindness). Included also were comments around the use of empathy, i.e., recognising and acknowledging emotions, and the importance of simply listening to all patient concerns. | 106 (19.0%) learner statements related to this subtheme. | “Be present and listen to concerns and emotions try not to fix situation or be to clinically focused treat the patient holistically, spiritually, emotionally and physically.” “Demonstrate your care and compassion through your kindness and patience in providing care.” |

| Hope | This pertains to the importance of the HCP maintaining a sense of hope and positivity, and of not providing ‘false hope’. | 33 (5.9%) learner statements related to this subtheme. | “Instil hope, but not false hope.” “Compassionately balancing hope while also being honest, open and clear.” “We can plan for the worst and still hope for the best” |

| Open-ended questions and discussion | This pertains to the importance of keeping communication between the patient, family, and HCP as open as possible, in order to encourage questions and continued discussion. | 31 (5.5%) learner statements related to this subtheme. | “Keep the communication lines open as they learn together what the future may look like.” “Through open dialogue patients can find encouragement and hopefully peace of mind to face the future whatever that holds.” |

| Subtheme | Description | No (%) Learners | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discuss, advise, and include patients and their families in end-of-life and future care planning | This pertains to ways in which HCP inform the patient and family about the range of supportive services, and care plan/treatment options that are available to them, as well as facilitating and encouraging open discussion about death, dying, and care planning for end of life. This included enabling the patient to express their goals and wishes, and what was most important to them when it came to their care and the time they had left. Developing a plan of care that enabled the patient to achieve their specific goals and wishes and involving the patient and family in the care planning process was very important. | 332 (59.4%) learner statements related to this subtheme. | “Informing the patient and their family about various options for future care” “Acknowledging that it is a time to start thinking and planning for End of Life Care” “Tease out what’s most important to the patient as those things can become goals of care.” |

| Patient comfort and quality of life | This pertains to HCP ensuring and prioritising patient comfort care, by providing pain relief and management of other symptoms to maximise their quality of life for the time they had left. | 54 (9.7%) learner statements related to this subtheme. | “As a nurse I would make sure the patient is comfortable having no pain” “Focus on managing symptoms and pain to maximise quality of life for however long that may be” |

| Multi-disciplinary/ team-based approach | This pertains to multidisciplinary staff members collaborating or using a team-based approach when discussing patient care plans together with the patient or relying on each other for information. | 28 (5.0%) learner statements related to this subtheme. | “It is a collaborative approach between health care professionals” “Refer patient and/or family to other members of the multidisciplinary team as appropriate” |

| Focus on the present | HCP described encouraging the patient to focus on the day-to-day and to take each day as it comes as they approach their end of life. | 20 (3.6%) learner statements related to this subtheme. | “Have short term goals to achieve, take each day as it comes” “The conversation needs to focus on the near future and not on the late future.” |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rawlings, D.; Winsall, M.; Yin, H.; Devery, K.; Morgan, D.D. Evaluation of an End-of-Life Essentials Online Education Module on Chronic Complex Illness End-of-Life Care. Healthcare 2020, 8, 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030297

Rawlings D, Winsall M, Yin H, Devery K, Morgan DD. Evaluation of an End-of-Life Essentials Online Education Module on Chronic Complex Illness End-of-Life Care. Healthcare. 2020; 8(3):297. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030297

Chicago/Turabian StyleRawlings, Deb, Megan Winsall, Huahua Yin, Kim Devery, and Deidre D. Morgan. 2020. "Evaluation of an End-of-Life Essentials Online Education Module on Chronic Complex Illness End-of-Life Care" Healthcare 8, no. 3: 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030297

APA StyleRawlings, D., Winsall, M., Yin, H., Devery, K., & Morgan, D. D. (2020). Evaluation of an End-of-Life Essentials Online Education Module on Chronic Complex Illness End-of-Life Care. Healthcare, 8(3), 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030297