Translational Lifestyle Medicine Approaches to Cardiovascular–Kidney–Metabolic Syndrome

Highlights

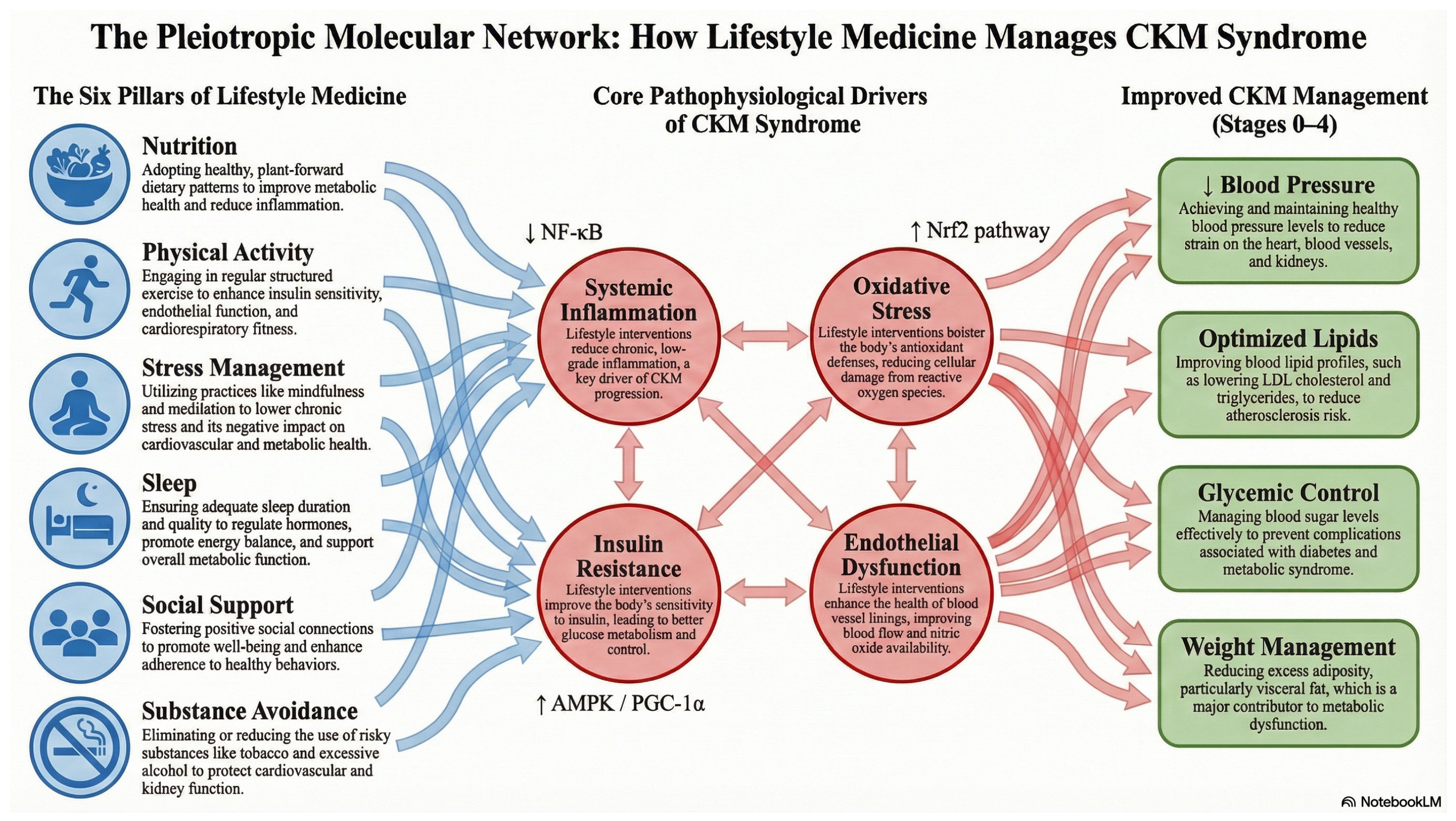

- Cardiovascular–Kidney–Metabolic (CKM) syndrome arises from a complex interplay among heart, kidney, and metabolic dysfunction, worsened by factors like inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance.

- Lifestyle medicine interventions—focusing on nutrition, physical activity, stress management, sleep hygiene, social support, and avoidance of risky substances—can offer significant benefits in managing CKM-related risk factors such as high blood pressure, unhealthy lipid profiles, and poor glucose control, when implemented consistently.

- Despite their potential benefits, lifestyle medicine strategies remain underutilized in clinical practice; integrating them as a core component of CKM prevention and management may meaningfully reduce risk burden.

- Future work and clinical pathways should emphasize personalized, integrative implementation (including digital health supports and sex-specific considerations) to address research gaps, reduce disparities, and optimize outcomes across diverse populations.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Current Knowledge Gaps

2.1. Understanding CKM Syndrome

2.2. Translational Approaches

| Intervention Pillar | Study | Target Mechanisms Relevant to CKM Syndrome | Key Findings Relevant to CKM Outcomes | Translational Insight/Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multimodal intensive lifestyle intervention (weight, diet, physical activity, behavioral counseling) | Intensive primary-care lifestyle intervention in underserved adults with obesity [45] and multicenter RCT in adults with type 2 diabetes [76]. | Reduction in overall adiposity (and central/visceral depots in imaging substudies of intensive lifestyle programs); improved insulin sensitivity and glycemic control; favorable changes in HDL-C and other cardiometabolic risk factors; modest effects on blood pressure. | In the pragmatic PROPEL trial, a 24-month intensive lifestyle intervention delivered by health coaches in primary care produced greater weight loss and clinically meaningful improvements in HDL-C and metabolic syndrome severity compared with usual care in a predominantly low-income, racially diverse population [45]. In Look AHEAD, intensive lifestyle intervention led to large, sustained weight loss and improvements in glycemic control and CV risk factors but did not significantly reduce major adverse cardiovascular events in the overall sample [76]. | Demonstrates that guideline-concordant intensive lifestyle programs can be implemented in real-world primary care and improve CKM risk factors, particularly in underserved populations [45]. The absence of overall event reduction in Look AHEAD highlights the need to integrate lifestyle with optimal pharmacotherapy and to identify subgroups who may derive the greatest CKM event reduction [76]. |

| Physical activity and structured exercise | Evidence-based exercise prescription across 26 chronic diseases [77]; exercise recommendations and vascular/autonomic responses in CKD, including acute exercise trials in moderate CKD [63,78,79,80]. | Increased cardiorespiratory fitness; improved endothelial function and arterial stiffness; favorable shifts in autonomic balance; reductions in blood pressure, insulin resistance, visceral adiposity, and low-grade inflammation; in CKD, acute improvements in FMD and autonomic recovery without evidence of acute renal harm. | Across cardiometabolic conditions, 150–300 min/week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity is associated with lower incidence of type 2 diabetes, improved blood pressure and lipid profiles, and reduced cardiovascular events in a clear dose–response pattern [77]. In non-dialysis CKD, supervised aerobic and resistance training is safe, improves exercise capacity and quality of life, and can modestly improve blood pressure and renal risk markers, though hard CKD and CV endpoints remain less well studied [78,79]. Acute crossover trials in moderate CKD show that a single bout of high-intensity interval or steady-state exercise augments flow-mediated dilation and improves cardiac autonomic recovery without signs of acute renal injury [63,80]. | Supports formal exercise prescription as a core CKM therapy, including for CKD, consistent with “exercise is medicine” frameworks [77]. Underlines the importance of embedding brief PA counseling, referral pathways, and monitoring of aerobic and resistance training targets within routine CKM care, tailored to comorbidities and functional capacity [78,79]. CKD-specific acute-exercise studies suggest a therapeutic window in which vascular and autonomic benefits can be obtained without immediate renal hemodynamic compromise, but larger and longer-term trials are needed to confirm effects on CKM outcomes [63,80]. For a detailed guide on stage-specific exercise modalities and dosing, see [11,65]. |

| Nutrition—Mediterranean and plant-forward lifestyle patterns | MEDLIFE cross-sectional analysis in US career firefighters [81] and whole-country cohort in Spain [82]. | High intake of minimally processed plant foods, extra-virgin olive oil, nuts, and legumes; lower intake of refined and ultra-processed foods; favorable fatty acid profile, combined with habitual physical activity, adequate rest, and social/convivial habits; collectively improves dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and vascular function. | Among 249 U.S. firefighters, higher adherence to the 26-item Mediterranean lifestyle (MEDLIFE) index was associated with markedly lower odds of metabolic syndrome and more favorable total and LDL-C (cholesterol) and total-to-HDL cholesterol ratios [81]. In a national Spanish cohort, higher MEDLIFE adherence was associated with lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome and significantly reduced all-cause and cardiovascular mortality over follow-up [82]. | Supports a Mediterranean-type lifestyle, integrating diet, movement, rest, and social connection, as a pragmatic Lifestyle Medicine strategy for CKM prevention and risk reduction in occupational and general populations [81,82]. Provides rationale for workplace and community interventions and for using tools such as MEDLIFE to operationalize lifestyle assessment in CKM clinical practice. |

| Sleep–exercise–postprandial cardiometabolic control | Experimental one-week sleep restriction in healthy adults [83,84] and acute partial sleep deprivation plus high-intensity exercise with high-fat feeding [9]. | Sleep restriction and circadian disruption impair insulin signaling, increase sympathetic activity and blood pressure, alter heart-rate variability, and worsen postprandial metabolic responses. Under conditions of acute sleep loss and high-fat intake, high-intensity exercise may modify or blunt expected cardioprotective patterns in brain–heart–metabolic coupling. | One week of restricting sleep to ~5–6 h/night in healthy adults reduced insulin sensitivity by ~20–25%, impaired glucose tolerance, and increased evening blood pressure changes consistent with a pre-diabetic phenotype independent of weight [83,84]. In a within-subject crossover study, acute partial sleep deprivation followed by morning high-intensity interval exercise and a high-fat breakfast altered network interactions between heart-rate variability and LDL cholesterol, suggesting modification or blunting of usual cardioprotective exercise patterns under sleep-deprived conditions [9]. | Elevates sleep and circadian health to a core Lifestyle Medicine pillar in CKM, indicating that exercise prescriptions and meal timing may need modification in sleep-restricted individuals [83,84]. The findings of Papadakis et al. [9] imply that high-intensity exercise performed after acute sleep loss and concurrent high-fat intake may not yield the full expected cardiometabolic benefit, reinforcing the need for coordinated interventions across sleep, exercise, and nutrition domains. |

| Positive social connection, loneliness, and lifestyle engagement | Objective activity and social isolation in older adults [85] and outcome-wide longitudinal analysis of loneliness and social isolation [86]. | Social isolation and loneliness reduce daily physical activity and increase sedentary time; disrupt neuroendocrine and inflammatory pathways; worsen depressive and anxiety symptoms; indirectly amplify CKM risk and undermine adherence to lifestyle and medical therapies. | In 267 older adults from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, greater social isolation (but not loneliness) was associated with lower 24 h activity counts, more sedentary time, and less light and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity objectively measured by accelerometry [85]. In a large US cohort of older adults, longitudinal changes in loneliness and social isolation were independently associated with multiple adverse physical, behavioral, and psychological outcomes; social isolation more strongly predicted mortality risk, whereas loneliness more strongly predicted psychological outcomes [86]. | Positions positive social connection and mental health support as essential components of Lifestyle Medicine in CKM, supporting routine screening for isolation and loneliness and incorporation of group-based LM programs and community linkage [85,86]. Reinforces the need for team-based care that integrates behavioral health, social work, and community partnerships to sustain lifestyle change and CKM risk reduction. |

| Avoidance of harmful substance use (tobacco and high-risk alcohol) | Smoking and CKD/CVD risk in large cohorts and meta-analyses [87,88], and prospective cohorts of alcohol consumption, all-cause mortality, CVD, and CKD [89,90], and large genetic–epidemiologic analyses of alcohol intake and CVD risk [91]. | Cigarette smoking promotes oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system; accelerates atherosclerosis; and contributes to glomerular injury and CKD progression. Smokeless tobacco products may also worsen CKM risk factors. High-risk alcohol use increases blood pressure, atrial fibrillation, cardiomyopathy, and overall cardiovascular mortality; relationships between low-to-moderate alcohol use and CKD/CVD risk are complex and may vary by CKM stage. | Meta-analyses and community-based cohorts show that current smoking is independently associated with a higher risk of incident CKD and faster decline in renal function, with risk increasing with cumulative exposure [87,88]. Studies of smoking timing suggest that lighting the first cigarette soon after waking, especially in the context of a poor diet, may further amplify CKD risk [92]. Prospective cohorts of alcohol consumption report U-shaped or inverse associations with CKD risk but increased CVD and all-cause mortality at higher intakes, and recent cohort and genetic–epidemiologic analyses do not support recommending alcohol consumption for cardiometabolic benefit [89,90,91]. | Underscores tobacco cessation as a non-negotiable Lifestyle Medicine priority across all CKM stages, given strong and consistent evidence that smoking increases CKD and CVD risk. Supports clear messaging that there is no safe level of tobacco use and that cessation should be aggressively supported with behavioral and pharmacologic tools. High-risk alcohol use should be systematically screened for and addressed as part of CKM management; contemporary evidence and recent analyses caution against recommending alcohol consumption for cardiometabolic benefit, particularly in patients with established CKM, and emphasize focusing on other lifestyle pillars instead [89,91]. |

| CKM framework and systems-level implementation of Lifestyle Medicine | AHA Presidential Advisory on CKM health [4] and conceptual commentary on CKM syndrome and multidisciplinary care [93]. | Integrated staging of CKM risk from optimal health to symptomatic disease; emphasis on interdependent pathways between obesity, dysglycemia, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure, with lifestyle behaviors as upstream drivers; positioning Lifestyle Medicine as foundational therapy across CKM stages. | The CKM advisory proposes CKM stages, recommends systematic assessment of CKM risk factors, and explicitly elevates lifestyle interventions as foundational therapy at every stage of CKM risk, alongside pharmacologic risk-factor modification [4]. Claudel and Verma (2023) [93] argue that the CKM construct is an opportunity to build multidisciplinary, equity-focused care models that integrate Lifestyle Medicine, cardiology, nephrology, endocrinology, and primary care. | Provides a policy-relevant scaffold for embedding Lifestyle Medicine into CKM prevention and treatment, aligning clinic, community, and policy actions and incentivizing team-based care and quality metrics that reward lifestyle implementation [4,93]. This framing can help health systems and payers justify Lifestyle Medicine programs as core CKM infrastructure rather than optional adjuncts. |

2.3. Opportunities for Novel Therapeutic Strategies

2.4. Molecular Mechanisms of Lifestyle Interventions

3. Integrations of Lifestyle Medicine

3.1. Nutrition

3.2. Physical Activity

3.3. Stress Management

3.4. Sleep Management

3.5. Social Support

3.6. Avoidance of Risky Substances

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Noubiap, J.J.; Nansseu, J.R.; Lontchi-Yimagou, E.; Nkeck, J.R.; Nyaga, U.F.; Ngouo, A.T.; Tounouga, D.N.; Tianyi, F.L.; Foka, A.J.; Ndoadoumgue, A.L.; et al. Global, regional, and country estimates of metabolic syndrome burden in children and adolescents in 2020: A systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2022, 6, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devarbhavi, H.; Asrani, S.K.; Arab, J.P.; Nartey, Y.A.; Pose, E.; Kamath, P.S. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 516–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swarup, S.; Ahmed, I.; Grigorova, Y.; Zeltser, R. Metabolic Syndrome. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ndumele, C.E.; Rangaswami, J.; Chow, S.L.; Neeland, I.J.; Tuttle, K.R.; Khan, S.S.; Coresh, J.; Mathew, R.O.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Carnethon, M.R.; et al. Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health: A Presidential Advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 148, 1606–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaborators, G.U.O.F. National-level and state-level prevalence of overweight and obesity among children, adolescents, and adults in the USA, 1990–2021, and forecasts up to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 2278–2298. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian, S.A.; Padda, I.; Johal, G. Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) syndrome: A state-of-the-art review. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, Z. Clinical exercising insights: Unveiling blood pressure’s prophetic role in anticipating future hypertension development. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2024, 31, 1070–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadakis, Z. Advancing the translational integration of lifestyle medicine in cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2025, 32, 1676–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, Z.; Garcia-Retortillo, S.; Koutakis, P. Effects of Acute Partial Sleep Deprivation and High-Intensity Interval Exercise on Postprandial Network Interactions. Front. Netw. Physiol. 2022, 2, 869787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, Z.; Etchebaster, M.; Garcia-Retortillo, S. Cardiorespiratory Coordination in Collegiate Rowing: A Network Approach to Cardiorespiratory Exercise Testing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, Z. Exercise in CKM Syndrome Progression: A Stage-Specific Approach to Cardiovascular, Metabolic, and Renal Health. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Frak, W.; Wojtasinska, A.; Lisinska, W.; Mlynarska, E.; Franczyk, B.; Rysz, J. Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Diseases: New Insights into Molecular Mechanisms of Atherosclerosis, Arterial Hypertension, and Coronary Artery Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.J.; Deedwania, P.; Acharya, T.; Aguilar, D.; Bhatt, D.L.; Chyun, D.A.; Di Palo, K.E.; Golden, S.H.; Sperling, L.S.; American Heart Association Diabetes Committee of the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health. Comprehensive Management of Cardiovascular Risk Factors for Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 145, e722–e759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virani, S.S.; Alonso, A.; Aparicio, H.J.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Cheng, S.; Delling, F.N.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2021 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e254–e743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kelly, A.C.; Michos, E.D.; Shufelt, C.L.; Vermunt, J.V.; Minissian, M.B.; Quesada, O.; Smith, G.N.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Garovic, V.D.; El Khoudary, S.R.; et al. Pregnancy and Reproductive Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease in Women. Circ. Res. 2022, 130, 652–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.M.; Shelly, L.; Murphy, B.S.; Kenneth, D.; Kochanek, M.A.; Arias, E. Mortality in the United States, 2021; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran, A.; Minhas, A.S.; Kazzi, B.; Varma, B.; Choi, E.; Thakkar, A.; Michos, E.D. Sex-specific differences in cardiovascular risk factors and implications for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Atherosclerosis 2023, 384, 117269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.S.; Huang, X.; Petito, L.C.; Bancks, M.P.; Ning, H.; Cameron, N.A.; Kershaw, K.N.; Kandula, N.R.; Carnethon, M.R.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; et al. Social and Psychosocial Determinants of Racial and Ethnic Differences in Cardiovascular Health in the United States Population. Circulation 2023, 147, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.S.; Ning, H.; Petito, L.C.; Kershaw, K.N.; Bancks, M.P.; Reis, J.P.; Rana, J.S.; Sidney, S.; Jacobs, D.R.; Kiefe, C.I., Jr.; et al. Associations of Clinical and Social Risk Factors with Racial Differences in Premature Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2022, 146, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- April-Sanders, A.K. Integrating Social Determinants of Health in the Management of Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e036518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Ji, R.; Li, Z.; Zhao, S.; Liu, R.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y. Impact of metabolic abnormalities on the association between normal-range urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio and cardiovascular mortality: Evidence from the NHANES 1999–2018. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2024, 16, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, V.; Al-Ghamdi, S.M.G.; Li, G.; Wu, M.S.; Stafylas, P.; Retat, L.; Card-Gowers, J.; Barone, S.; Cabrera, C.; Garcia Sanchez, J.J. Global Economic Burden Associated with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Pragmatic Review of Medical Costs for the Inside CKD Research Programme. Adv. Ther. 2023, 40, 4405–4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States. 2023. Available online: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/kidney-disease (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Care, D. Standards of care in diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, S1–S267. [Google Scholar]

- ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Aroda, V.R.; Bannuru, R.R.; Brown, F.M.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Hilliard, M.E.; Isaacs, D.; Johnson, E.L.; et al. 11. Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, S191–S202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasi, A.; Cosola, C.; Caggiano, G.; Cimmarusti, M.T.; Palieri, R.; Acquaviva, P.M.; Rana, G.; Gesualdo, L. Obesity-Related Chronic Kidney Disease: Principal Mechanisms and New Approaches in Nutritional Management. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 925619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, Y.; Tremblay, J.; Mesa, R.A.; Parsons, B.; Chavez, E.; Contreras, G.; Fornoni, A.; Raij, L.; Swift, S.; Elfassy, T. Associations Between Albuminuria and Mortality Among US Adults by Demographic and Comorbidity Factors. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e030773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahemuti, N.; Zou, J.; Liu, C.; Xiao, Z.; Liang, F.; Yang, X. Urinary Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio in Normal Range, Cardiovascular Health, and All-Cause Mortality. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2348333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Streja, E.; Tsujimoto, T.; Kobayashi, H. Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio within normal range and all-cause or cardiovascular mortality among U.S. adults enrolled in the NHANES during 1999–2015. Ann. Epidemiol. 2021, 55, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabaka, A.; Cases-Corona, C.; Fernandez-Juarez, G. Therapeutic Insights in Chronic Kidney Disease Progression. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 645187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, P.L.; Castillo-Garcia, A.; Saco-Ledo, G.; Santos-Lozano, A.; Lucia, A. Physical exercise: A polypill against chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2024, 39, 1384–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marassi, M.; Fadini, G.P. The cardio-renal-metabolic connection: A review of the evidence. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Li, Y.; Zhao, M.; Yu, X.; Zhang, C.; Magnussen, C.G.; Xi, B. Association of the American Heart Association’s new “Life’s Essential 8” with all-cause and cardiovascular disease-specific mortality: Prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciardullo, S.; Ballabeni, C.; Trevisan, R.; Perseghin, G. Metabolic Syndrome, and Not Obesity, Is Associated with Chronic Kidney Disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 2021, 52, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurt, F.G.; Ganz, M.J.; Herzog, C.; Bose, K.; Mertens, P.R.; Chatzikyrkou, C. Association of metabolic syndrome and chronic kidney disease. Obes. Rev. 2024, 25, e13649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrominski, J.W.; Arnold, S.V.; Butler, J.; Fonarow, G.C.; Hirsch, J.S.; Palli, S.R.; Donato, B.M.K.; Parrinello, C.M.; O’Connell, T.; Collins, E.B.; et al. Prevalence and Overlap of Cardiac, Renal, and Metabolic Conditions in US Adults, 1999–2020. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 1050–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Lei, L.; Wang, W.; Ding, W.; Yu, Y.; Pu, B.; Peng, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Y. Social Risk Profile and Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome in US Adults. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e034996. [Google Scholar]

- Zoccali, C. A New Clinical Entity Bridging the Cardiovascular System and the Kidney: The Chronic Cardiovascular-Kidney Disorder. Cardiorenal Med. 2025, 15, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudel, S.E.; Schmidt, I.M.; Waikar, S.; Verma, A. Prevalence and Cumulative Incidence of Mortality Associated with Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome in the United States. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Ostrominski, J.W.; Vaduganathan, M. Prevalence of Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome Stages in US Adults, 2011–2020. JAMA 2024, 331, 1858–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.B.; Eknoyan, G. Cardiorenal Syndrome: An Evolutionary Appraisal. Circ. Heart Fail. 2024, 17, e011510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarelli, A.A.; Ordovás, J. Epigenetics of Early Cardiometabolic Disease: Mechanisms and Precision Medicine. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 1648–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Perez, O.; Reyes-Garcia, R.; Modrego-Pardo, I.; Lopez-Martinez, M.; Soler, M.J. Are we ready for an adipocentric approach in people living with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease? Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfae039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.S.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Barone Gibbs, B.; Beaton, A.Z.; Boehme, A.K.; et al. 2024 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 149, e347–e913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochsmann, C.; Dorling, J.L.; Martin, C.K.; Newton, R.L.; Apolzan, J.W., Jr.; Myers, C.A.; Denstel, K.D.; Mire, E.F.; Johnson, W.D.; Zhang, D.; et al. Effects of a 2-Year Primary Care Lifestyle Intervention on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Cluster-Randomized Trial. Circulation 2021, 143, 1202–1214. [Google Scholar]

- Jakicic, J.M.; Apovian, C.M.; Barr-Anderson, D.J.; Courcoulas, A.P.; Donnelly, J.E.; Ekkekakis, P.; Hopkins, M.; Lambert, E.V.; Napolitano, M.A.; Volpe, S.L. Physical Activity and Excess Body Weight and Adiposity for Adults. American College of Sports Medicine Consensus Statement. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2024, 56, 2076–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Aroda, V.R.; Bannuru, R.R.; Brown, F.M.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Hilliard, M.E.; Isaacs, D.; Johnson, E.L.; et al. 5. Facilitating Positive Health Behaviors and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, S68–S96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Petersen, K.S.; Despres, J.P.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Deedwania, P.; Furie, K.L.; Lear, S.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Lobelo, F.; Morris, P.B.; et al. Strategies for Promotion of a Healthy Lifestyle in Clinical Settings: Pillars of Ideal Cardiovascular Health: A Science Advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 144, e495–e514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, L. The impact of nutrition and lifestyle modification on health. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 97, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A.N.; Schauer, P.R.; Beddhu, S.; Kramer, H.; le Roux, C.W.; Purnell, J.Q.; Sunwold, D.; Tuttle, K.R.; Jastreboff, A.M.; Kaplan, L.M. Obstacles and opportunities in managing coexisting obesity and CKD: Report of a scientific workshop cosponsored by the national kidney foundation and the obesity society. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2022, 80, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, P. Promoting exercise in older people to support healthy ageing. Nurs. Stand. 2022, 37, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L.E.; Despres, J.P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C.J.; Lear, S.A.; Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Sanders, P.; et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e984–e1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, M.N.; Neeland, I.J. Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease: An Update. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2022, 22, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1966–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Liu, Z. Mediating role of inflammatory biomarkers on the association of physical activity, sedentary behaviour with chronic kidney disease: A cross-sectional study in NHANES 2007–2018. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e084920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, J.B.S.; Dias, T.; Cardoso, B.E.P.; de Paiva Sousa, M.; Sousa, T.G.V.; Araujo, D.S.C.; Marreiro, D.D.N. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction: Impact on Metabolic Changes? Horm. Metab. Res. 2022, 54, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbay, M.; Copur, S.; Yildiz, A.B.; Tanriover, C.; Mallamaci, F.; Zoccali, C. Physical exercise in kidney disease: A commonly undervalued treatment modality. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 54, e14105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Tuttle, K.R.; Perkovic, V.; Libby, P.; MacFadyen, J.G. Inflammation drives residual risk in chronic kidney disease: A CANTOS substudy. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 4832–4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, Z. NIH cuts: A costly retreat-defunding precision lifestyle medicine amid the cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic crisis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2025, 329, H432–H438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, C.; Spanos, M.; Li, G.; Lu, R.; Bei, Y.; Xiao, J. Exercise training maintains cardiovascular health: Signaling pathways involved and potential therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobanputra, R.; Sargeant, J.A.; Almaqhawi, A.; Ahmad, E.; Arsenyadis, F.; Webb, D.R.; Herring, L.Y.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J.; Yates, T. The effects of weight-lowering pharmacotherapies on physical activity, function and fitness: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes. Rev. 2023, 24, e13553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsse, J.S.; Peterson, M.N.; Papadakis, Z.; Taylor, J.K.; Hess, B.W.; Schwedock, N.; Allison, D.C.; Griggs, J.O.; Wilson, R.L.; Grandjean, P.W. The Effect of Acute Aerobic Exercise on Biomarkers of Renal Health and Filtration in Moderate-CKD. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2024, 95, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadakis, Z.; Grandjean, P.W.; Forsse, J.S. Effects of Acute Exercise on Cardiac Autonomic Response and Recovery in Non-Dialysis Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2023, 94, 812–825. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Sasaki, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Hayashi, H.; Ako, S.; Tanaka, Y. Effects of exercise on kidney and physical function in patients with non-dialysis chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioni Maturana, F.; Martus, P.; Zipfel, S.; NIEß, A.M. Effectiveness of HIIE versus MICT in Improving Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Health and Disease: A Meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2021, 53, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, H.; Wells, S.; Mehta, S. Are competing-risk models superior to standard Cox models for predicting cardiovascular risk in older adults? Analysis of a whole-of-country primary prevention cohort aged ≥ 65 years. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 51, 604–614. [Google Scholar]

- Klevjer, M.; Nordeidet, A.N.; Bye, A. The genetic basis of exercise and cardiorespiratory fitness—Relation to cardiovascular disease. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2023, 33, 100649. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.; Caldwell, A.R.; Mesquida, C.; Ladell, A.J.M.; Encarnacion-Martinez, A.; Tual, A.; Denys, A.; Cameron, B.; Van Hooren, B.; Parr, B.; et al. Estimating the Replicability of Sports and Exercise Science Research. Sports Med. 2025, 55, 2659–2679. [Google Scholar]

- Balafoutas, L.; Celse, J.; Karakostas, A.; Umashev, N. Incentives and the replication crisis in social sciences: A critical review of open science practices. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2025, 114, 102327. [Google Scholar]

- Pawel, S.; Heyard, R.; Micheloud, C.; Held, L. Replication of null results: Absence of evidence or evidence of absence? eLife 2024, 12, RP92311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Errington, T.M.; Mathur, M.; Soderberg, C.K.; Denis, A.; Perfito, N.; Iorns, E.; Nosek, B.A. Investigating the replicability of preclinical cancer biology. eLife 2021, 10, e71601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Huang, L.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, F. Interventions to increase physical activity level in patients with whole spectrum chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren. Fail. 2023, 45, 2255677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutten, L.J.F.; Ridgeway, J.L.; Griffin, J.M. Advancing translation of clinical research into practice and population health impact through implementation science. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2024, 99, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J.M.M.; Roever, L.; Ramasamy, A.; Pereira, R.; Carneiro, I.; Krustrup, P.; Povoas, S.C.A. Statistical heterogeneity in meta-analysis of hypertension and exercise training: A meta-review. J. Sports Sci. 2023, 41, 2033–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolland, M.J.; Avenell, A.; Grey, A. Publication integrity: What is it, why does it matter, how it is safeguarded and how could we do better? J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2025, 55, 267–286. [Google Scholar]

- Look, A.R.G.; Wing, R.R.; Bolin, P.; Brancati, F.L.; Bray, G.A.; Clark, J.M.; Coday, M.; Crow, R.S.; Curtis, J.M.; Egan, C.M.; et al. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Saltin, B. Exercise as medicine—Evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2015, 25, 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, K.L. Exercise and chronic kidney disease: Current recommendations. Sports Med. 2005, 35, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johansen, K.L.; Painter, P. Exercise in individuals with CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2012, 59, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsse, J.S.; Papadakis, Z.; Peterson, M.N.; Taylor, J.K.; Hess, B.W.; Schwedock, N.; Allison, D.C.; Griggs, J.O.; Wilson, R.L.; Grandjean, P.W. The Influence of an Acute Bout of Aerobic Exercise on Vascular Endothelial Function in Moderate Stages of Chronic Kidney Disease. Life 2022, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershey, M.S.; Sotos-Prieto, M.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Christophi, C.A.; Moffatt, S.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Kales, S.N. The Mediterranean lifestyle (MEDLIFE) index and metabolic syndrome in a non-Mediterranean working population. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2494–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotos-Prieto, M.; Ortola, R.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Garcia-Esquinas, E.; Martinez-Gomez, D.; Lopez-Garcia, E.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F. Association between the Mediterranean lifestyle, metabolic syndrome and mortality: A whole-country cohort in Spain. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buxton, O.M.; Marcelli, E. Short and long sleep are positively associated with obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease among adults in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, O.M.; Pavlova, M.; Reid, E.W.; Wang, W.; Simonson, D.C.; Adler, G.K. Sleep restriction for 1 week reduces insulin sensitivity in healthy men. Diabetes 2010, 59, 2126–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrempft, S.; Jackowska, M.; Hamer, M.; Steptoe, A. Associations between social isolation, loneliness, and objective physical activity in older men and women. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.H.; Nakamura, J.S.; Berkman, L.F.; Chen, F.S.; Shiba, K.; Chen, Y.; Kim, E.S.; VanderWeele, T.J. Are loneliness and social isolation equal threats to health and well-being? An outcome-wide longitudinal approach. SSM Popul. Health 2023, 23, 101459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Wang, L.; Ma, Z.; Zhong, L.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; He, L.; Su, X. Cigarette smoking and chronic kidney disease in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017, 32, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.C.; Xu, Z.L.; Zhao, M.Y.; Xu, K. The Association Between Smoking and Renal Function in People Over 20 Years Old. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 870278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Luo, S. Association between alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease: A prospective cohort study. Medicine 2024, 103, e38857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, L.; Chen, A.; Wu, Y.; Wang, G.; Xie, X.; He, Q.; Xue, Y.; Lin, J.; Zheng, Z.; et al. Relationship between moderate alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality across different stages of Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) Syndrome: A cohort study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 36, 104287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddinger, K.J.; Emdin, C.A.; Haas, M.E.; Wang, M.; Hindy, G.; Ellinor, P.T.; Kathiresan, S.; Khera, A.V.; Aragam, K.G. Association of Habitual Alcohol Intake with Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e223849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Heianza, Y.; Qi, L. Smoking Timing, Healthy Diet, and Risk of Incident CKD Among Smokers: Findings from UK Biobank. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2024, 84, 593–600 e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudel, S.E.; Verma, A. Cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome: A step toward multidisciplinary and inclusive care. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 2104–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, P.C. The New Field of Network Physiology: Building the Human Physiolome. Front. Netw. Physiol. 2021, 1, 711778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.L.; Quiroz, J.C.; Kocaballi, A.B.; Fat, S.C.M.; Dao, K.P.; Gehringer, H.; Chow, C.K.; Laranjo, L. Personalized mobile technologies for lifestyle behavior change: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Prev. Med. 2021, 148, 106532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.K.; Carr, M.J.; Kontopantelis, E.; Leelarathna, L.; Thabit, H.; Emsley, R.; Buchan, I.; Mamas, M.A.; van Staa, T.P.; Sattar, N.; et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular and Heart Failure Events with SGLT2 Inhibitors, GLP-1 Receptor Agonists, and Their Combination in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuffield Department of Population Health Renal Studies Group; SGLT2 Inhibitor Meta-Analysis Cardio-Renal Trialists’ Consortium. Impact of diabetes on the effects of sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors on kidney outcomes: Collaborative meta-analysis of large placebo-controlled trials. Lancet 2022, 400, 1788–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff, A.M.; Aronne, L.J.; Ahmad, N.N.; Wharton, S.; Connery, L.; Alves, B.; Kiyosue, A.; Zhang, S.; Liu, B.; Bunck, M.C. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, D.; Abrahamsson, N.; Davies, M.; Hesse, D.; Greenway, F.L.; Jensen, C.; Lingvay, I.; Mosenzon, O.; Rosenstock, J.; Rubio, M.A.; et al. Effect of Continued Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Placebo on Weight Loss Maintenance in Adults with Overweight or Obesity: The STEP 4 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 1414–1425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jastreboff, A.M.; Kushner, R.F. New Frontiers in Obesity Treatment: GLP-1 and Nascent Nutrient-Stimulated Hormone-Based Therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Med. 2023, 74, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattar, N.; Lee, M.M.Y.; Kristensen, S.L.; Branch, K.R.H.; Del Prato, S.; Khurmi, N.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Lopes, R.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Pratley, R.E.; et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, Z.; Madeira, M.M.; Koliatsis, D.; Tsirka, S.E. Convergence of endothelial dysfunction, inflammation and glucocorticoid resistance in depression-related cardiovascular diseases. BMC Immunol. 2024, 25, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscoli, S.; Ifrim, M.; Russo, M.; Candido, F.; Sanseviero, A.; Milite, M.; Di Luozzo, M.; Marchei, M.; Sangiorgi, G.M. Current Options and Future Perspectives in the Treatment of Dyslipidemia. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, B.; Sikand, G.; Dineen, E.H.; Malik, S.; Barseghian El-Farra, A. Lipid-Lowering Nutraceuticals for an Integrative Approach to Dyslipidemia. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suder, A.; Makiel, K.; Targosz, A.; Kosowski, P.; Malina, R.M. Positive Effects of Aerobic-Resistance Exercise and an Ad Libitum High-Protein, Low-Glycemic Index Diet on Irisin, Omentin, and Dyslipidemia in Men with Abdominal Obesity: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelopoulos, N.; Paparodis, R.D.; Androulakis, I.; Boniakos, A.; Argyrakopoulou, G.; Livadas, S. Low Dose Monacolin K Combined with Coenzyme Q10, Grape Seed, and Olive Leaf Extracts Lowers LDL Cholesterol in Patients with Mild Dyslipidemia: A Multicenter, Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merican, A.F.; Ramlan, E.I.; Zamrod, Z.; Alwi, Z. Personalised genomics for healthy lifestyle and wellness. Asian J. Med. Biomed. 2018, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Nacis, J.S.; Labrador, J.P.H.; Ronquillo, D.G.D.; Rodriguez, M.P.; Dablo, A.; Frane, R.D.; Madrid, M.L.; Santos, N.L.C.; Carrillo, J.J.V.; Fernandez, M.G.; et al. A study protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of a gene-based nutrition and lifestyle recommendation for weight management among adults: The MyGeneMyDiet® study. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1238234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, A.T.; Bray, M.; Acayo Laker, P.; Bourdon, J.L.; Dorsey, A.; Zalik, M.; Pietka, A.; Salyer, P.; Waters, E.A.; Chen, L.S.; et al. Participatory Design of a Personalized Genetic Risk Tool to Promote Behavioral Health. Cancer Prev. Res. 2020, 13, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klevjer, M.; Nordeidet, A.N.; Hansen, A.F.; Madssen, E.; Wisloff, U.; Brumpton, B.M.; Bye, A. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies New Genetic Determinants of Cardiorespiratory Fitness: The Trondelag Health Study. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2022, 54, 1534–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singar, S.; Nagpal, R.; Arjmandi, B.H.; Akhavan, N.S. Personalized Nutrition: Tailoring Dietary Recommendations through Genetic Insights. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallin, M.; Hall, J.; Herlihy, M.; Gelman, E.J.; Stone, M.B. A pilot retrospective study of a physician-directed and genomics-based model for precision lifestyle medicine. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1239737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, B.A.; Jae, S.Y. Physical Activity, Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: Part 1. Pulse 2024, 12, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, B.A.; Jae, S.Y. Physical Activity, Cardiorespiratory Fitness, and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: Part 2. Pulse 2024, 12, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesies-Grau, J.; Dionne, V.; Latour, É.; Gayda, M.; Besnier, F.; Gagnon, D.; Debray, A.; Gagnon, C.; Tessier, A.J.; Simard, F.; et al. Enhanced cardiac rehabilitation with ultra-Processed food reduction and time-restricted eating resolves metabolic syndrome and prediabetes in coronary heart patients: The DIABEPIC-1 study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2024, 31, zwae175–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, C.S.; Nielsen, S.M.; Bjorner, J.; Johansen, M.Y.; Christensen, R.; Vaag, A.; Lieberman, D.E.; Pedersen, B.K.; Langberg, H.; Ried-Larsen, M.; et al. One-year intensive lifestyle intervention and improvements in health-related quality of life and mental health in persons with type 2 diabetes: A secondary analysis of the U-TURN randomized controlled trial. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2021, 9, e001840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benasi, G.; Gostoli, S.; Zhu, B.; Offidani, E.; Artin, M.G.; Gagliardi, L.; Rignanese, G.; Sassi, G.; Fava, G.A.; Rafanelli, C. Well-Being Therapy and Lifestyle Intervention in Type 2 Diabetes: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychosom. Med. 2022, 84, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febles, R.M.; Martín, A.G.; Báez, D.S.; Mallén, P.I.D.; Miquel, R.; Torres, S.E.; Caso, M.A.C.; Perera, C.C.; Martin, L.D.; Luis-Lima, S.; et al. #3439 Exercise, Metabolic Syndrome and Chronic Kidney Disease (Ckd): The Ex-Red Study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023, 38, gfad063c_3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eboreime-Oikeh, I.O.; Ibezim, H.U.; Harmony, U.; Oikeh, O.S. Prevalence of Kidney Dysfunction and Its Relationship with Components of Metabolic Syndrome among Adult Outpatients in a Nigerian Tertiary Hospital. West. Afr. J. Med. 2024, 41, S26–S27. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, N.C.; Burton, J.O.; Graham-Brown, M.P.M.; Stensel, D.J.; Viana, J.L.; Watson, E.L. Exercise and chronic kidney disease: Potential mechanisms underlying the physiological benefits. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2023, 19, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteves, J.V.; Stanford, K.I. Exercise as a tool to mitigate metabolic disease. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2024, 327, C587–C598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, A.W.C.; Li, H.; Xia, N. Impact of Lifestyles (Diet and Exercise) on Vascular Health: Oxidative Stress and Endothelial Function. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 2020, 1496462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bianco, V.; Ferreira, G.D.S.; Bochi, A.P.G.; Pinto, P.R.; Rodrigues, L.G.; Furukawa, L.N.S.; Okamoto, M.M.; Almeida, J.A.; da Silveira, L.K.R.; Santos, A.S.; et al. Aerobic Exercise Training Protects Against Insulin Resistance, Despite Low-Sodium Diet-Induced Increased Inflammation and Visceral Adiposity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.X.; Zhou, M.; Ma, H.L.; Qiao, Y.B.; Li, Q.S. The Role of Chronic Inflammation in Various Diseases and Anti-inflammatory Therapies Containing Natural Products. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 1576–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliulo, L.; Bondi, D.; Pini, N.; Marramiero, L.; Di Filippo, E.S. The wonder exerkines—Novel insights: A critical state-of-the-art review. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2022, 477, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nani, A.; Murtaza, B.; Sayed Khan, A.; Khan, N.A.; Hichami, A. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Polyphenols Contained in Mediterranean Diet in Obesity: Molecular Mechanisms. Molecules 2021, 26, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapti, E.; Adamantidi, T.; Efthymiopoulos, P.; Kyzas, G.Z.; Tsoupras, A. Potential Applications of the Anti-Inflammatory, Antithrombotic and Antioxidant Health-Promoting Properties of Curcumin: A Critical Review. Nutraceuticals 2024, 4, 562–595. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Song, G.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Zou, D.; Li, H.; Hu, C.; Zhao, H.; Yan, Y. Caffeine promotes the production of Irisin in muscles and thus facilitates the browning of white adipose tissue. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 108, 105702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, G.N.; Jaworsky, K.; Basu, A. The Effects of Plant-Derived Phytochemical Compounds and Phytochemical-Rich Diets on Females with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Scoping Review of Clinical Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Porto, A.; Cavarape, A.; Colussi, G.; Casarsa, V.; Catena, C.; Sechi, L.A. Polyphenols Rich Diets and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugal, J.K.; Malhi, A.S.; Ramazani, N.; Yee, B.; Di Caro, M.V.; Lei, K. Non-Pharmacological Therapy in Heart Failure and Management of Heart Failure in Special Populations—A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, E.; Oikonomou, C.; Nychas, G.; Dimitriadis, G.D. Effects of Diet, Lifestyle, Chrononutrition and Alternative Dietary Interventions on Postprandial Glycemia and Insulin Resistance. Nutrients 2022, 14, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landen, S.; Jacques, M.; Hiam, D.; Alvarez-Romero, J.; Schittenhelm, R.B.; Shah, A.D.; Huang, C.; Steele, J.R.; Harvey, N.R.; Haupt, L.M.; et al. Sex differences in muscle protein expression and DNA methylation in response to exercise training. Biol. Sex. Differ. 2023, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Lopez, O.; Milagro, F.I.; Riezu-Boj, J.I.; Martinez, J.A. Epigenetic signatures underlying inflammation: An interplay of nutrition, physical activity, metabolic diseases, and environmental factors for personalized nutrition. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 70, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, C.Q.; Parnell, L.D.; Lee, Y.C.; Zeng, H.; Smith, C.E.; McKeown, N.M.; Arnett, D.K.; Ordovas, J.M. The impact of alcoholic drinks and dietary factors on epigenetic markers associated with triglyceride levels. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1117778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, U.; Nazir, A.; Ahmad, S.; Asghar, N. Spices for Diabetes, Cancer and Obesity Treatment. In Dietary Phytochemicals: A Source of Novel Bioactive Compounds for the Treatment of Obesity, Cancer and Diabetes; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2021; pp. 169–191. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, C.D.; Vadiveloo, M.K.; Petersen, K.S.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Springfield, S.; Van Horn, L.; Khera, A.; Lamendola, C.; Mayo, S.M.; Joseph, J.J.; et al. Popular Dietary Patterns: Alignment with American Heart Association 2021 Dietary Guidance: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 147, 1715–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Zeng, X.; Fu, P. The impact of weight loss on renal function in individuals with obesity and type 2 diabetes: A comprehensive review. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1320627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Garzon, M.D.; Wang, M.; Li, V.L.; Lyu, X.; Wei, W.; Tung, A.S.; Raun, S.H.; Zhao, M.; Coassolo, L.; Islam, H.; et al. A beta-hydroxybutyrate shunt pathway generates anti-obesity ketone metabolites. Cell 2025, 188, 175–186.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bains, S.; Giudicessi, J.R.; Odening, K.E.; Ackerman, M.J. State of Gene Therapy for Monogenic Cardiovascular Diseases. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2024, 99, 610–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.; Slater, S.; White, M.; Wood, B.; Contreras, A.; Corvalan, C.; Gupta, A.; Hofman, K.; Kruger, P.; Laar, A.; et al. Towards unified global action on ultra-processed foods: Understanding commercial determinants, countering corporate power, and mobilising a public health response. Lancet 2025, 406, 2703–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Louzada, M.L.; Steele-Martinez, E.; Cannon, G.; Andrade, G.C.; Baker, P.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Bonaccio, M.; Gearhardt, A.N.; Khandpur, N.; et al. Ultra-processed foods and human health: The main thesis and the evidence. Lancet 2025, 406, 2667–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scrinis, G.; Popkin, B.M.; Corvalan, C.; Duran, A.C.; Nestle, M.; Lawrence, M.; Baker, P.; Monteiro, C.A.; Millett, C.; Moubarac, J.C.; et al. Policies to halt and reverse the rise in ultra-processed food production, marketing, and consumption. Lancet 2025, 406, 2685–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakicic, J.M.; Rogers, R.J.; Lang, W.; Gibbs, B.B.; Yuan, N.; Fridman, Y.; Schelbert, E.B. Impact of weight loss with diet or diet plus physical activity on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and cardiovascular disease risk factors: Heart Health Study randomized trial. Obesity 2022, 30, 1039–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomiuk, T.; Niezgoda, N.; Mamcarz, A.; Sliz, D. Physical activity in metabolic syndrome. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1365761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceviz, E. Relationship Between Visceral Fat Tissue and Exercise. Türk Spor Bilim. Derg. 2024, 7, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlefield, L.A.; Papadakis, Z.; Rogers, K.M.; Moncada-Jimenez, J.; Taylor, J.K.; Grandjean, P.W. The effect of exercise intensity and excess postexercise oxygen consumption on postprandial blood lipids in physically inactive men. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 42, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, Z.; Forsse, J.S.; Peterson, M.N. Acute partial sleep deprivation and high-intensity interval exercise effects on postprandial endothelial function. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2020, 120, 2431–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhuli, K.; Naureen, Z.; Medori, M.C.; Fioretti, F.; Caruso, P.; Perrone, M.A.; Nodari, S.; Manganotti, P.; Xhufi, S.; Bushati, M.; et al. Physical activity for health. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E150–E159. [Google Scholar]

- Goeder, D.; Kropfl, J.M.; Angst, T.; Hanssen, H.; Hauser, C.; Infanger, D.; Maurer, D.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R.; Schmidt-Trucksass, A.; Konigstein, K. VascuFit: Aerobic exercise improves endothelial function independent of cardiovascular risk: A randomized-controlled trial. Atherosclerosis 2024, 399, 118631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, J.; Milani, M.; Verboven, K.; Cipriano, G.; Hansen, D., Jr. Exercise intensity prescription in cardiovascular rehabilitation: Bridging the gap between best evidence and clinical practice. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1380639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucuk, O. Walk More, Eat Less, Don’t Stress. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2022, 31, 1673–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngan, H.Y.; Chong, Y.Y.; Chien, W.T. Effects of mindfulness- and acceptance-based interventions on diabetes distress and glycaemic level in people with type 2 diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet. Med. 2021, 38, e14525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doskaliuk, B. Stress-relief, meditation, and their pervasive influence on health and anti-aging: A holistic perspective. Anti-Aging East. Eur. 2023, 2, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, Z.; Walsh, S.M.; Morgan, G.B.; Deal, P.J.; Stamatis, A. Is Mindfulness the Common Ground Between Mental Toughness and Self-Compassion in Student Athletes? A Cross-Sectional Study. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berjaoui, C.; Tesfasilassie Kibrom, B.; Ghayyad, M.; Joumaa, S.; Talal Al Labban, N.; Nazir, A.; Kachouh, C.; Akanmu Moradeyo, A.; Wojtara, M.; Uwishema, O. Unveiling the sleep-cardiovascular connection: Novel perspectives and interventions-A narrative review. Health Sci. Rep. 2023, 6, e1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavat, M.; Mirsanjari, M.; Arabiat, D.; Smyth, A.; Whitehead, L. The Role of Sleep Curtailment on Leptin Levels in Obesity and Diabetes Mellitus. Obes. Facts 2021, 14, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, T.; Basalely, A.; Singer, P.; Castellanos, L.; Sethna, C.B. The association between sleep duration and cardiometabolic risk among children and adolescents in the United States (US): A NHANES study. Child. Care Health Dev. 2024, 50, e13273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, Z.; Forsse, J.S.; Stamatis, A. High-Intensity Interval Exercise Performance and Short-Term Metabolic Responses to Overnight-Fasted Acute-Partial Sleep Deprivation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, C.C.; Vincent, G.E.; Coates, A.M.; Khalesi, S.; Irwin, C.; Dorrian, J.; Ferguson, S.A. A Time to Rest, a Time to Dine: Sleep, Time-Restricted Eating, and Cardiometabolic Health. Nutrients 2022, 14, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenton, S.; Burrows, T.L.; Collins, C.E.; Rayward, A.T.; Murawski, B.; Duncan, M.J. Efficacy of a Multi-Component m-Health Diet, Physical Activity, and Sleep Intervention on Dietary Intake in Adults with Overweight and Obesity: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yim, H.E.; Yoo, K.H. Obesity and chronic kidney disease: Prevalence, mechanism, and management. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2021, 64, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvathareddy, V.P.; Ella, K.M.; Shah, M.; Navaneethan, S.D. Treatment options for managing obesity in chronic kidney disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2021, 30, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, Z.; Forsse, J.S.; Peterson, M.N. Effects of High-Intensity Interval Exercise and Acute Partial Sleep Deprivation on Cardiac Autonomic Modulation. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2021, 92, 824–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, L.; Tansey, E. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; Queen Mary University of London: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, R.A.; Khalsa, S.S.S.; Vyas, A.K.; Rahimian, R. Sex-Specific Impacts of Exercise on Cardiovascular Remodeling. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacGregor, K.; Ellefsen, S.; Pillon, N.J.; Hammarstrom, D.; Krook, A. Sex differences in skeletal muscle metabolism in exercise and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2025, 21, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shing, C.L.H.; Bond, B.; Moreau, K.L.; Coombes, J.S.; Taylor, J.L. The therapeutic role of exercise training during menopause for reducing vascular disease. Exp. Physiol. 2024; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, S.K.; SAngadi, S.; Bhargava, A.; Harper, J.; Hirschberg, A.L.; DLevine, B.; LMoreau, K.; JNokoff, N.; Stachenfeld, N.S.; Bermon, S. The Biological Basis of Sex Differences in Athletic Performance: Consensus Statement for the American College of Sports Medicine. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2023, 55, 2328–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, H. Obesity: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutics. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 706978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Zhao, X.; Wu, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Hou, L. High-intensity interval training versus moderate-intensity continuous training on patient quality of life in cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeranki, Y.R.; Garcia-Retortillo, S.; Papadakis, Z.; Stamatis, A.; Appiah-Kubi, K.O.; Locke, E.; McCarthy, R.; Torad, A.A.; Kadry, A.M.; Elwan, M.A.; et al. Detecting Psychological Interventions Using Bilateral Electromyographic Wearable Sensors. Sensors 2024, 24, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Hippel, P.T. Is Psychological Science Self-Correcting? Citations Before and After Successful and Failed Replications. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 17, 1556–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derksen, M.; Morawski, J. Kinds of Replication: Examining the Meanings of “Conceptual Replication” and “Direct Replication”. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 17, 1490–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aert, R.C.; Wicherts, J.M.; Van Assen, M.A. Publication bias examined in meta-analyses from psychology and medicine: A meta-meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Guo, Y.; Hua, G.; Guo, C.; Gong, S.; Li, M.; Yang, Y. Exercise training modalities in prediabetes: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1308959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Papadakis, Z. Translational Lifestyle Medicine Approaches to Cardiovascular–Kidney–Metabolic Syndrome. Healthcare 2026, 14, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010051

Papadakis Z. Translational Lifestyle Medicine Approaches to Cardiovascular–Kidney–Metabolic Syndrome. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010051

Chicago/Turabian StylePapadakis, Zacharias. 2026. "Translational Lifestyle Medicine Approaches to Cardiovascular–Kidney–Metabolic Syndrome" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010051

APA StylePapadakis, Z. (2026). Translational Lifestyle Medicine Approaches to Cardiovascular–Kidney–Metabolic Syndrome. Healthcare, 14(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010051