Exploring the Association Between Physical Activity, Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy, Perceived Self-Burden, and Social Isolation Among Older Adults in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Concept of Variables

2.1.1. Physical Activity

2.1.2. Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy

2.1.3. Self-Perceived Burden

2.1.4. Social Isolation

2.2. Hypothesis

3. Methods

3.1. Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Information on Physical Activities for the Elderly

4.2. Assessment of the Measurement Model Reliability and Validity

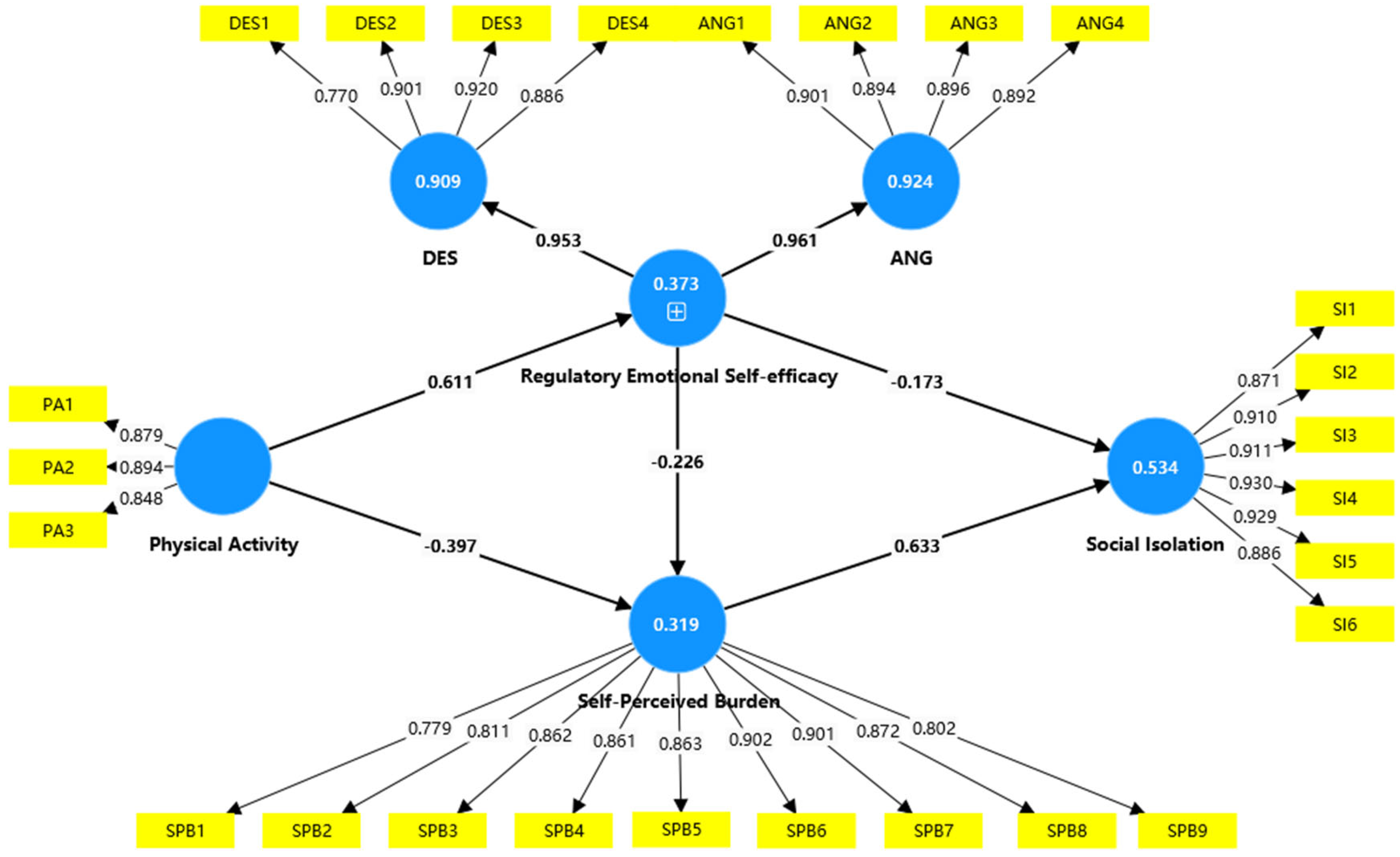

4.3. Hypothesis Testing Results

4.4. Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, L.; Konttinen, H.; Martikainen, P.; Silventoinen, K. Socioeconomic status and physical functioning: A longitudinal study of older Chinese people. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2018, 73, 1315–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Qi, J.; Zuo, P.; Yin, P.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Li, L. The mortality trends of falls among the elderly adults in the mainland of China, 2013–2020: A population-based study through the National Disease Surveillance Points system. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2022, 19, 100336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girdhar, R.; Srivastava, V.; Sethi, S.r. Managing mental health issues among elderly during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Geriatr. Care 2020, 7, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, K.; Gupta, D. Perceived loneliness among elderly people. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2016, 7, 553. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, M.J.; Wu, F.; Guo, Y.; Robledo, L.M.G.; O’Donnell, M.; Sullivan, R.; Yusuf, S. The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. Lancet 2015, 385, 549–562. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Saltin, B. Evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in chronic disease. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2006, 16, 3–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Cao, F.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, X. The role of dietary intake of live microbes in the association between leisure-time physical activity and depressive symptoms: A population-based study. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 49, 1014–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, K.R. The influence of physical activity on mental well-being. Public Health Nutr. 1999, 2, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionigi, R. Resistance training and older adults’ beliefs about psychological benefits: The importance of self-efficacy and social interaction. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 723–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinger, P.; Dunn, J.; Panisset, M.; Dow, B.; Batchelor, F.; Biddle, S.J.; Duque, G.; Hill, K.D. Challenges and lessons learnt from the ENJOY project: Recommendations for future collaborative research implementation framework with local governments for improving the environment to promote physical activity for older people. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C.; O’Sullivan, R.; Caserotti, P.; Tully, M.A. Consequences of physical inactivity in older adults: A systematic review of reviews and meta-analyses. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMonnies, C.W. Intraocular pressure and glaucoma: Is physical exercise beneficial or a risk? J. Optom. 2016, 9, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czaja, S.J.; Moxley, J.H.; Rogers, W.A. Social support, isolation, loneliness, and health among older adults in the PRISM randomized controlled trial. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 728658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotkamp-Mothes, N.; Slawinsky, D.; Hindermann, S.; Strauss, B. Coping and psychological well being in families of elderly cancer patients. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2005, 55, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Purol, M.F.; Weidmann, R.; Chopik, W.J.; Kim, E.S.; Baranski, E.; Schwaba, T.; Lodi-Smith, J.; Whitbourne, S.K. Health and well-being consequences of optimism across 25 years in the Rochester adult longitudinal study. J. Res. Pers. 2022, 99, 104237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Liang, H.; Qin, X.; Ge, Y.; Xiang, N.; Liu, E. Optimism and survival: Health behaviors as a mediator—A ten-year follow-up study of Chinese elderly people. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, C.E.; Dugan, E. Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. J. Aging Health 2012, 24, 1346–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Peng, S.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Liao, X.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, X. Factors associated with social isolation in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2023, 24, 322–330.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poscia, A.; Stojanovic, J.; La Milia, D.I.; Duplaga, M.; Grysztar, M.; Moscato, U.; Onder, G.; Collamati, A.; Ricciardi, W.; Magnavita, N. Interventions targeting loneliness and social isolation among the older people: An update systematic review. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 102, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, G.S.; McPherson, B.D. Becoming involved in physical activity and sport: A process of socialization. Phys. Act. Hum. Growth Dev. 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiremath, C. Impact of sports on mental health. Int. J. Physiol. Nutr. Phys. Educ. 2019, 1, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, F.; Jing, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H. Effect of physical activity on social interaction anxiety among Beijing drifters: The mediating roles of interpersonal competence and perceived stress. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2023, 51, 12825E–12835E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Di Giunta, L.; Eisenberg, N.; Gerbino, M.; Pastorelli, C.; Tramontano, C. Assessing regulatory emotional self-efficacy in three countries. Psychol. Assess. 2008, 20, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastman, C.; Marzillier, J.S. Theoretical and methodological difficulties in Bandura’s self-efficacy theory. Cognit. Ther. Res. 1984, 8, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigger, S.E.; Vo, T. Self-Perceived Burden: A Critical Evolutionary Concept Analysis. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2022, 24, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousineau, N.; McDowell, I.; Hotz, S.; Hébert, P. Measuring chronic patients’ feelings of being a burden to their caregivers: Development and preliminary validation of a scale. Med. Care 2003, 41, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.J.; Béland, M.; Clyde, M.; Gariépy, G.; Pagé, V.; Badawi, G.; Rabasa-Lhoret, R.; Schmitz, N. Association of diabetes with anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2013, 74, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, N.C.; Lu, Q.; Mak, W.W. Self-perceived burden mediates the relationship between self-stigma and quality of life among Chinese American breast cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 3337–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.O.; Taylor, R.J.; Nguyen, A.W.; Chatters, L. Social isolation, depression, and psychological distress among older adults. J. Aging Health 2018, 30, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machielse, A. Theories on social contacts and social isolation. In Social Isolation in Modern Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hawkley, L.C. Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2009, 13, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Sarrionandia, A.; Mikolajczak, M.; Gross, J.J. Integrating emotion regulation and emotional intelligence traditions: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.-L.; Arthur, A.; Avis, M. Using self-efficacy theory to develop interventions that help older people overcome psychological barriers to physical activity: A discussion paper. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 1690–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yang, J. Alleviating doctors’ emotional exhaustion through sports involvement during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating roles of regulatory emotional self-efficacy and perceived stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nes, L.S.; Liu, H.; Patten, C.A.; Rausch, S.M.; Sloan, J.A.; Garces, Y.I.; Cheville, A.L.; Yang, P.; Clark, M.M. Physical activity level and quality of life in long term lung cancer survivors. Lung Cancer 2012, 77, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.C.; Gilmore, L.A. Physical activity reduces the risk of recurrence and mortality in cancer patients. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2020, 48, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, J.; Cao, B.; Wang, F.; Luo, L.; Xu, J. Mediating effects of self-efficacy, coping, burnout, and social support between job stress and mental health among young Chinese nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, G.; Perinelli, E.; De Longis, E.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Theodorou, A.; Borgogni, L.; Caprara, G.V.; Cinque, L. Job burnout: The contribution of emotional stability and emotional self-efficacy beliefs. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 91, 823–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.T.; Hsieh, C.H.; Chiang, M.C.; Chen, J.S.; Chang, W.C.; Chou, W.C.; Hou, M.M. Impact of high self-perceived burden to others with preferences for end-of-life care and its determinants for terminally ill cancer patients: A prospective cohort study. Psycho-Oncology 2017, 26, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berking, M.; Ebert, D.; Cuijpers, P.; Hofmann, S.G. Emotion regulation skills training enhances the efficacy of inpatient cognitive behavioral therapy for major depressive disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 2013, 82, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesar, S.; Koortzen, P.; Oosthuizen, R.M. The relationship between emotional intelligence and stress management. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2009, 35, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merluzzi, T.V.; Philip, E.J.; Vachon, D.O.; Heitzmann, C.A. Assessment of self-efficacy for caregiving: The critical role of self-care in caregiver stress and burden. Palliat. Support. Care 2011, 9, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A.; Caprara, G.V.; Barbaranelli, C.; Gerbino, M.; Pastorelli, C. Role of affective self-regulatory efficacy in diverse spheres of psychosocial functioning. Child Dev. 2003, 74, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuji, H.; Tetsunaga, T.; Tetsunaga, T.; Nishida, K.; Misawa, H.; Ozaki, T. The factors driving self-efficacy in intractable chronic pain patients: A retrospective study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2019, 14, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, K.F.; Awal, A.; Mazumder, H.; Munni, U.R.; Majumder, K.; Afroz, K.; Tabassum, M.N.; Hossain, M.M. Social cognitive theory-based health promotion in primary care practice: A scoping review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Parpura-Gill, A. Loneliness in older persons: A theoretical model and empirical findings. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2007, 19, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, V.T.; Portela, M.C.; Camacho, L.A.; Atie, S.; Lima, M.J. Assessment of social support and its association to depression, self-perceived health and chronic diseases in elderly individuals residing in an area of poverty and social vulnerability in Rio de Janeiro City, Brazil. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.M.; Frost, A. Loneliness and psychological distress in women diagnosed with ovarian cancer: Examining the role of self-perceived burden, social support seeking, and social network diversity. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2022, 29, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, L.M.; Hill, K.D.; Finch, C.F.; Clemson, L.; Haines, T. The association between physical activity and social isolation in community-dwelling older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R.M.; Young, J.A.; Harvey, J.T.; Charity, M.J.; Payne, W.R. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, C.; Geldenhuys, G.; Gott, M. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: An integrative review. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 26, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pels, F.; Kleinert, J. Loneliness and physical activity: A systematic review. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2016, 9, 231–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D. Stress level and its relation with physical activity in higher education. Chin. Ment. Health J. 1994, 8, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gore, P.A., Jr. Academic self-efficacy as a predictor of college outcomes: Two incremental validity studies. J. Career Assess. 2006, 14, 92–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, L.A. Self-perceived burden in cancer patients: Validation of the Self-perceived Burden Scale. Cancer Nurs. 2007, 30, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, N.R., Jr.; Feinn, R.; Casey, E.; Dixon, J. Psychometric evaluation of the social isolation scale in older adults. Gerontologist 2020, 60, e491–e501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 6, 816p. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Koppius, O.R. Predictive analytics in information systems research. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992; 103p. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K.A.; Stine, R. Direct and indirect effects: Classical and bootstrap estimates of variability. Sociol. Methodol. 1990, 20, 115–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, M.; van Tilburg, T.G. Social exclusion and social isolation in later life. In Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences; Ferraro, K.F., Carr, D., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, K.; Scharf, T.; Keating, N. Social exclusion of older persons: A scoping review and conceptual framework. Eur. J. Ageing 2017, 14, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, N.; Liang, J. Stress, social support, and psychological distress among the Chinese elderly. J. Gerontol. 1993, 48, P282–P291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAuley, E.; Konopack, J.F.; Motl, R.W.; Morris, K.S.; Doerksen, S.E.; Rosengren, K.R. Physical activity and quality of life in older adults: Influence of health status and self-efficacy. Ann. Behav. Med. 2006, 31, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brüchert, T.; Quentin, P.; Baumgart, S.; Bolte, G. Barriers, facilitating factors, and intersectoral collaboration for promoting active mobility for healthy aging—A qualitative study within local government in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutros, G.E.H.; Morais, J.A.; Karelis, A.D. Current concepts in healthy aging and physical activity: A viewpoint. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2019, 27, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Site, A.; Lohan, E.S.; Jolanki, O.; Valkama, O.; Hernandez, R.R.; Latikka, R.; Alekseeva, D.; Vasudevan, S.; Afolaranmi, S.; Ometov, A.; et al. Managing perceived loneliness and social-isolation levels for older adults: A survey with focus on wearables-based solutions. Sensors 2022, 22, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Title | Profiles | Survey (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 113 (47.7%) |

| Female | 124 (52.3%) | |

| Age | <65 | 149 (62.9%) |

| 65–70 | 80 (33.8%) | |

| >70 | 8 (3.3%) | |

| Housing situation | Living alone | 60 (25.3%) |

| Living with family | 177 (74.7%) | |

| Self-assessed health | Well | 4 (1.7%) |

| Fair | 151 (63.7%) | |

| Poor | 82 (34.6%) | |

| Medical insurance | Yes | 221 (93.2%) |

| No | 16 (6.8%) |

| Title | Profiles | Survey (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Activity Intensity | Light physical activity (e.g., walking, radio calisthenics) | 16.03% |

| Light to moderate physical activity (e.g., jogging, Tai Chi) | 64.56% | |

| Moderate to high-intensity physical activity (e.g., cycling, table tennis) | 7.59% | |

| High-intensity physical activity with a short duration (e.g., badminton, tennis) | 8.86% | |

| High-intensity physical activity with a long duration (e.g., swimming, running) | 2.95% | |

| Activity Duration | Less than 10 min | 12.66% |

| 11–20 min | 16.88% | |

| 21–30 min | 33.33% | |

| 31–59 min | 18.99% | |

| 60 min or more | 18.14% | |

| Activity Frequency | Less than once a month | 11.39% |

| 2–3 times a month | 27.43% | |

| 1–2 times a week | 32.49% | |

| 3–5 times a week | 17.72% | |

| Daily | 10.97% |

| Items | Loading | Cα | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Activity (PA) | 0.846 | 0.907 | 0.764 | |

| PA1 | 0.879 | 0.797 | ||

| PA2 | 0.894 | 0.721 | ||

| PA3 | 0.848 | 0.819 | ||

| Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy (RES) | 0.943 | 0.953 | 0.716 | |

| Perceived Self-Efficacy in Managing Despondency/Distress (DES) | 0.893 | 0.926 | 0.759 | |

| DES1 | 0.77 | 0.944 | ||

| DES2 | 0.901 | 0.934 | ||

| DES3 | 0.92 | 0.931 | ||

| DES4 | 0.886 | 0.934 | ||

| Perceived Self-Efficacy in Managing Anger/Irritation (ANG) | 0.918 | 0.942 | 0.803 | |

| ANG1 | 0.901 | 0.932 | ||

| ANG2 | 0.894 | 0.934 | ||

| ANG3 | 0.896 | 0.934 | ||

| ANG4 | 0.892 | 0.934 | ||

| Self-Perceived Burden (SPB) | 0.952 | 0.959 | 0.725 | |

| SPB1 | 0.779 | 0.950 | ||

| SPB2 | 0.811 | 0.948 | ||

| SPB3 | 0.862 | 0.946 | ||

| SPB4 | 0.861 | 0.946 | ||

| SPB5 | 0.863 | 0.946 | ||

| SPB6 | 0.902 | 0.943 | ||

| SPB7 | 0.901 | 0.944 | ||

| SPB8 | 0.872 | 0.946 | ||

| SPB9 | 0.802 | 0.950 | ||

| Social Isolation (SI) | 0.956 | 0.965 | 0.822 | |

| SI1 | 0.871 | 0.953 | ||

| SI2 | 0.910 | 0.947 | ||

| SI3 | 0.911 | 0.947 | ||

| SI4 | 0.930 | 0.944 | ||

| SI5 | 0.929 | 0.944 | ||

| SI6 | 0.886 | 0.951 |

| RES | PA | SPB | SI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RES | 0.846 | |||

| PA | 0.611 | 0.874 | ||

| SPB | −0.469 | −0.535 | 0.851 | |

| SI | −0.470 | −0.532 | 0.714 | 0.906 |

| No. | Path | β | SEs | T Statistics | p Values | LLIC | ULIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PA → RES | 0.611 | 0.612 | 15.199 | 0.000 | 0.529 | 0.687 |

| H2 | PA → SPB | −0.397 | −0.395 | 5.013 | 0.000 | −0.543 | −0.237 |

| H3 | RES → SPB | −0.226 | −0.231 | 2.159 | 0.031 | −0.433 | −0.026 |

| H4 | RES → SI | −0.173 | −0.179 | 2.544 | 0.011 | −0.318 | −0.055 |

| H5 | SPB → SI | 0.633 | 0.629 | 10.711 | 0.000 | 0.503 | 0.731 |

| R2 | Adjusted R2 | Q2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RES | 0.373 | 0.370 | 0.264 |

| SPB | 0.319 | 0.313 | 0.226 |

| SI | 0.534 | 0.530 | 0.433 |

| No | Path | Effect | Boot SE | T Statistics | p Values | Boot LLIC | Boot ULIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H6 | Total indirect effect of PA → SI | −0.445 | −0.447 | 8.557 | 0.000 | −0.547 | −0.344 |

| Total Effect of PA → SI | −0.445 | −0.447 | 8.557 | 0.000 | −0.547 | −0.344 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, S.; Peng, H.; Jing, L.; Wang, H.; Chen, S. Exploring the Association Between Physical Activity, Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy, Perceived Self-Burden, and Social Isolation Among Older Adults in China. Healthcare 2025, 13, 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060687

Yang S, Peng H, Jing L, Wang H, Chen S. Exploring the Association Between Physical Activity, Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy, Perceived Self-Burden, and Social Isolation Among Older Adults in China. Healthcare. 2025; 13(6):687. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060687

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Shicheng, Huimin Peng, Longjun Jing, Huilin Wang, and Shuyin Chen. 2025. "Exploring the Association Between Physical Activity, Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy, Perceived Self-Burden, and Social Isolation Among Older Adults in China" Healthcare 13, no. 6: 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060687

APA StyleYang, S., Peng, H., Jing, L., Wang, H., & Chen, S. (2025). Exploring the Association Between Physical Activity, Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy, Perceived Self-Burden, and Social Isolation Among Older Adults in China. Healthcare, 13(6), 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060687