Abstract

Background/Objectives: Despite growing interest in oral frailty as a public health issue, no nationwide study has assessed regional differences in oral frailty awareness, and the factors associated with such differences remain unclear. This study investigated regional differences in oral frailty awareness among older adults in Japan and identified the associated individual- and municipal-level factors, focusing on local policy measures and community-based oral health programs. Methods: A cross-sectional analysis was conducted using data from the 2022 wave of the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study. The analytical sample comprised 20,330 community-dwelling adults aged ≥65 years from 66 municipalities. Awareness of oral frailty was assessed via self-administered questionnaires. Individual- and municipal-level variables were analyzed using multilevel Poisson regression models to calculate prevalence ratios (PRs). Results: Awareness of oral frailty varied widely across municipalities, ranging from 15.3% to 47.1%. Multilevel analysis showed that being male (PR: 1.10), having ≤9 years (PR: 1.10) or 10 to 12 years of education (PR: 1.04), having oral frailty (PR: 1.04), and lacking civic participation (PR: 1.06) were significantly associated with lack of awareness. No significant associations were found with municipal-level variables such as dental health ordinances, volunteer training programs, or population density. Conclusions: The study found substantial regional variation in oral frailty awareness. However, this variation was explained primarily by individual-level characteristics. Public health strategies should focus on enhancing awareness among socially vulnerable groups—especially men, individuals with low educational attainment, and those not engaged in civic activities—through targeted interventions and community-based initiatives.

1. Introduction

Frailty has emerged as an increasingly important public health issue amid global population aging, including in Japan [1]. More recently, oral frailty has been recognized as a pivotal aspect of overall frailty, with prior studies highlighting associations between oral health status and general frailty among older adults [2,3]. The Japan Dental Association defines oral frailty as a progressive condition involving age-related deterioration in oral health, such as tooth loss, poor oral hygiene, and a decline in oral function, combined with decreased interest in oral care and diminished physical and mental resilience [4]. This condition may lead to eating dysfunction, and a consequent further deterioration of both physical and cognitive capacities. Oral frailty has been associated with a range of adverse outcomes, including poor nutritional status [5], sarcopenia [6], increased falling risk [7], depression [8], cognitive decline [9], and reduced civic participation [10], highlighting its broad impact on older adults’ health and well-being.

Awareness of oral frailty plays a critical role in promoting preventive behaviors. Higher levels of awareness have been shown to encourage proactive health practices, including better oral hygiene and regular dental care, thereby reducing the risk of oral diseases [11,12]. Accordingly, the Japan Dental Association has set a 50% awareness of oral frailty by 2025 as a national target [13]. However, a recent prefectural survey reported an awareness rate of only 29.6%, indicating a substantial gap [14]. Moreover, awareness tends to be lower among socially vulnerable groups such as older adults, individuals at risk of oral frailty, and those requiring home dental care [14]. Recent studies have also shown that strong civic engagement and participation in community activities are associated with higher levels of awareness and a reduced risk of oral frailty [15]. These findings suggest that both individual characteristics and community-level social capital may play a crucial role in fostering awareness and encouraging preventive action.

In response to the growing need for prevention, municipalities in Japan have implemented various oral frailty initiatives in collaboration with dental associations, dental hygienist organizations, and other stakeholders. These include community-based education, oral health screening, individualized guidance, the distribution of informational materials, and public lectures [16,17]. Some municipalities have enacted dental health ordinances that address oral frailty explicitly. While these efforts are expected to raise awareness, few studies have systematically examined their impact. Assessing the effectiveness of such measures requires a consideration of both individual- and community-level factors, including how local policy frameworks and social infrastructure contribute to awareness and behavioral change.

The aim of this study was to investigate regional differences in oral frailty awareness among older adults in Japan and to identify the associated individual- and municipal-level factors, with a focus on local policy measures and community-based oral health programs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

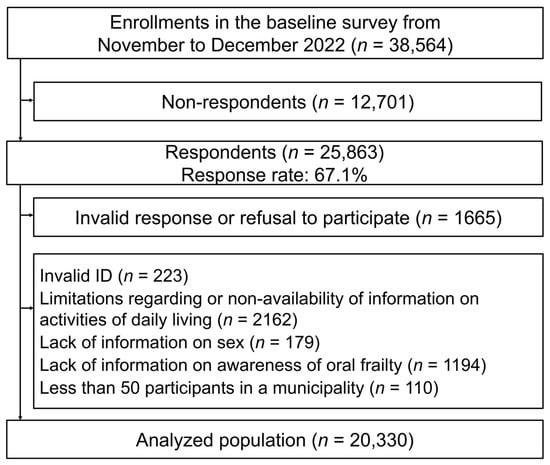

This study utilized cross-sectional data taken from the 2022 wave of the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES), a nationwide epidemiological study on the social determinants of healthy aging among nondisabled individuals aged ≥65 years. In 2022, the JAGES survey targeted 338,742 community-dwelling older adults from 75 municipalities in 24 prefectures across Japan, of whom 228,119 responded. A subsample-specific version of the self-administered questionnaire (Version D), which included items on oral frailty awareness, was distributed to 38,564 randomly selected individuals residing in 69 municipalities. Of these, 25,863 individuals returned completed questionnaires (response rate: 67.1%; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participant selection process.

To these respondents, several exclusion criteria were applied: individuals who refused to participate or who submitted invalid responses (n = 1665), invalid respondent IDs (n = 223), no or insufficient information regarding independence in daily living (n = 2162), no data on sex (n = 179), or no responses related to awareness of oral frailty (n = 1194). In addition, participants residing in municipalities with fewer than 50 respondents were excluded (n = 110) to ensure the stability of the municipal-level estimates. After these exclusions, 20,330 participants from 66 municipalities were included in the analytical sample used for this study.

2.2. Variables

2.2.1. Dependent Variable

The dependent variable was awareness of oral frailty. This was assessed using the question, “Are you familiar with the term ‘oral frailty’?” Responses of “very familiar” and “have heard of the term” were classified as “aware,” while the response of “not familiar” was classified as “not aware.”

2.2.2. Individual-Level Independent Variables

Individual-level variables were obtained from a self-administered questionnaire; these included sex, age group, educational attainment, equivalent income, current illness, oral frailty, drinking habits, smoking habits, frequency of going out, average daily walking time, frequency of meeting friends, civic participation, reciprocity, social cohesion, family structure, and housing type. Educational attainment was categorized as “≤9 years,” “10−12 years,” “≥13 years,” and “unknown” (i.e., other responses or missing data). Equivalent income was calculated by dividing household income by the square root of the number of household members to adjust for household size. Presence of current illness was based on a self-reported diagnosis of any of the following: hypertension; stroke; heart disease; diabetes; hyperlipidemia; respiratory disease; gastrointestinal, liver, or gallbladder disease; kidney or prostate disease; musculoskeletal disease; trauma; cancer; hematological or immune disorders; depression; dementia; Parkinson’s disease; or visual/hearing impairment. Responses were dichotomized as “yes” or “no.”

Civic participation, reciprocity, and social cohesion were assessed using methods described by the previous study [18]. Social cohesion was measured using three items: (1) “Do you think individuals in your community are generally trustworthy?” (2) “Do you think individuals in your community often try to be helpful to others?” and (3) “Do you have an attachment to your local area?” Participants who answered “yes” to at least one of the three questions were categorized as having social cohesion, and the rest were categorized as not having it. Civic participation was assessed using the question, “How often do you participate in a volunteer group, a sports group, or a hobby activity?” Participants who reported participating in any of the three group types at least once a month (from “1−3 times a month” to “≥4 times a week”) were categorized as “yes,” and those who responded “a few times a year” or “never” were categorized as “no.” Reciprocity was assessed using three items: (1) “Do you have someone who listens to your concerns and complaints?” (emotional support received), (2) “Do you listen to someone else’s concerns and complaints?” (emotional support provided), and (3) “Do you have someone who looks after you when you are sick?” (instrumental support received). Participants who answered “yes” to at least one item were categorized as having reciprocity; those who answered “no” to all items were categorized as not having reciprocity.

Drinking habits were categorized as “current” (currently drinking), “past” (quit within the past ≥5 years), “non-drinker” (never drank), and “unknown” (non-response). Smoking habits were classified similarly: “current,” “past,” “non-smoker,” and “unknown.”

Frequency of going out was grouped into five categories: “≥5 times a week,” “4 times a week,” “2−3 times a week,” “once a week,” and “not going out” (which combined “1−3 times a month” or “a few times a year”). Non-responses were categorized as “unknown.” Average daily walking time was classified as “<30 min,” “30−59 min,” and “≥60 min” (combining “60−89 min” and “≥90 min”); non-responses were coded as “unknown.”

Oral frailty was assessed using a predictive model [19], which incorporates age, number of teeth, difficulty eating tough foods, and choking. The number of teeth was self-reported based on several categories (≥20, 10−19, 1−9, 0) and dichotomized as ≥20 or ≤19. Difficulty eating tough foods was assessed with the question, “Do you have any difficulties eating tough foods now compared with 6 months previously?” Choking was assessed using the question, “Have you recently choked on your tea or soup?” Both were dichotomized into “yes” or “no” responses, based on the Basic Checklist used in Japan’s long-term care insurance system [20].

2.2.3. Municipal-Level Independent Variable

This study obtained information on municipal oral frailty prevention programs via a postal questionnaire survey conducted between 20 December 2022 and 31 January 2023, targeting 66 municipalities. Responses were received from 48 municipalities, yielding a response rate of 72.7%. For non-responding municipalities, the relevant information was collected from official municipal websites. The survey collected information on the respondent’s name, contact information, and job title, as well as the presence or absence of municipal dental health ordinances and (if present) whether they included measures explicitly related to oral frailty. The same questions were asked regarding prefectural dental health ordinances. In addition, the survey inquired about the existence of oral frailty prevention initiatives implemented before fiscal year 2022, such as leaflet distribution, community lectures, and volunteer training programs for residents.

Information on population and municipal habitable land area (in hectares) was obtained from the 2020 Social and Demographic Statistics [21]. Population density (persons/km2) was calculated by dividing the total population by the municipal area, with hectares converted to square kilometers. Based on population density, municipalities were classified into four categories: metropolitan area (≥4000 persons/km2), urban area (2000−3999 persons/km2), semi-urban area (200−1999 persons/km2), and rural area (<200 persons/km2) [22].

Municipal-level social capital was calculated as the mean of aggregated individual-level binary variables (coded as 0 or 1) for civic participation, reciprocity, and social cohesion within each municipality.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

At the individual level, associations between awareness of oral frailty and each covariate were assessed using the chi-square test. At the municipal level, associations between the municipal-level variables and the proportion of individuals who were aware of oral frailty were examined using the Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis test. A two-level multilevel Poisson regression analysis was conducted, with lack of oral frailty awareness as the dependent variable (coded as 1 for “not aware” and 0 for “aware”). For Model 1, each individual- and municipal-level variable was entered into the model separately. For the municipal-level analysis, variables with a p-value of <0.20 in the univariate analysis were included. Model 2 included only sex and age. Model 3 included all individual- and municipal-level variables.

As a sensitivity analysis, cross-tabulations and two-level multilevel Poisson regression analyses were conducted using an alternative definition of the dependent variable. In this analysis, only the “very familiar” responses were categorized as “aware,” while “have heard of the term” and “not familiar” were combined and categorized as “not aware.” This approach was based on the assumption that individuals who have merely “heard of the term” are less likely to engage in health-promoting behaviors than are those who are “very familiar” with the concept of oral frailty. Furthermore, higher oral health literacy has been associated with more frequent preventive dental visits and better oral health outcomes [23].

All statistical analyses, except the multilevel analyses, were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 28.0 (SPSS Japan, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The multilevel analyses were conducted using MLwiN version 3.10 (Centre for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol, UK). A two-sided significance level of 5% was used for all tests.

2.4. Ethical Issues

The 2022 JAGES survey was approved by the Ethics Committee on Research of Human Subjects at the Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine (approval no. M10460) and the Ethics Committee of Kanagawa Dental University (approval no. 988). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.

3. Results

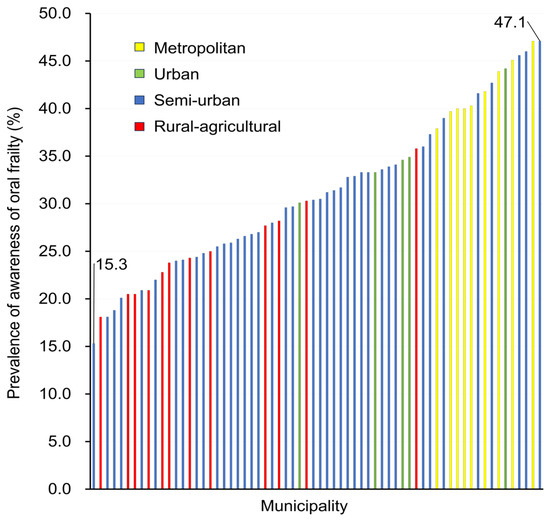

Figure 2 presents the awareness levels concerning oral frailty across the 66 municipalities, which ranged from 15.3% to 47.1%, with a median of 30.4%. Awareness was generally lower in rural and agricultural areas and higher in metropolitan areas.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of awareness of oral frailty across 66 municipalities.

Table 1 presents the associations between awareness of oral frailty and individual-level variables. Significant associations were observed for all variables (p < 0.001). Individuals who were not aware of oral frailty were more likely to be male and older; have lower educational attainment and income; report no current illness; exhibit signs of oral frailty; have a history of alcohol consumption; currently smoke; go out infrequently; walk less per day on average; meet friends less frequently; and lack civic participation, reciprocity, and social cohesion. They were also more likely to live in two-person households and rental housing.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants (n = 20,330).

Table 2 presents the associations between awareness levels concerning oral frailty and municipal-level variables. The variables that showed a statistically significant association (p < 0.20) included explicit oral frailty measures in prefectural dental health ordinances, the presence of volunteer training programs for residents as part of oral frailty-related initiatives, and population density.

Table 2.

Association between awareness of oral frailty and municipality-level variables (n = 66).

Table 3 displays the results of the multilevel Poisson regression analysis. In Model 1, the following variables were significantly associated with lack of awareness of oral frailty: being male; age ≥85 years (reference: 65−69 years); educational attainment of ≤9 years or 10−12 years (reference: ≥13 years); equivalent income ≤JPY 1.99 million (reference: ≥JPY 4 million); presence of oral frailty; current or past alcohol consumption (reference: none); current or past smoking (reference: none); not going out at all (reference: ≥5 times per week); average daily walking time of <30 min (reference: ≥60 min); infrequent contact with friends (reference: at least once a week); lack of civic participation; lack of social cohesion; housing type—owner-occupied (single-family) or rented (reference: owner-occupied, multi-family); and residence in semi-urban or rural areas (reference: metropolitan area). The municipal-level variance in the null model was 0.0008 (standard error = 0.0005). In Model 2, which included only sex and age, both variables were significantly associated with lack of awareness of oral frailty. In Model 3, which included all individual- and municipal-level variables, the following remained significantly associated with lower oral frailty awareness: male sex, educational attainment of ≤9 years or 10−12 years (reference: ≥13 years), presence of oral frailty, and lack of civic participation.

Table 3.

Prevalence ratios for lack of awareness of oral frailty in individual- and municipal-level variables calculated using a multilevel Poisson regression model.

The results of the multilevel Poisson regression analysis from the sensitivity analysis (Table 4) indicated that lack of awareness of oral frailty was significantly associated with the following characteristics: male sex; educational attainment of ≤9 years or 10−12 years (reference: ≥13 years); equivalent income of ≤JPY 1.99 million (reference: ≥JPY 4 million); and lack of civic participation.

Table 4.

Sensitivity analyses showing the prevalence of a conservative definition of awareness (‘very familiar’ only) and prevalence ratios for lack of awareness (‘have heard of the term’ and ‘not familiar’) using the multilevel Poisson regression model.

4. Discussion

This study is the first to investigate regional differences in awareness of oral frailty across Japan and to examine the associated individual- and municipal-level factors using multilevel analysis. The results revealed a substantial variation in awareness, ranging from 15% to 47%, a more than threefold difference across municipalities. The municipalities included in this study were those that responded to an invitation from researchers to engage in collaborative research efforts, including regional assessments through inter-municipality comparisons. As participation was limited to municipalities with a demonstrated enthusiasm for joint research, the disparities observed in inter-municipality comparisons may be underestimated. Consequently, the generalizability of these findings to municipalities with fewer officials committed to research and evidence-based policymaking may be constrained. These considerations highlight the necessity for tailored strategies to enhance awareness of oral frailty, with careful attention to regional contexts and inequities.

The results of the multilevel analysis (Model 3) showed that, at the individual level, persons who were men, had lower educational attainment, exhibited oral frailty, and lacked civic participation were independently associated with lack of awareness of oral frailty. At the municipal level, regional factors such as the presence of prefectural ordinances, oral frailty prevention programs, social capital, and population density were not significantly associated with awareness. Furthermore, the municipal-level variance, which was already low (0.0008) in the null model, decreased slightly from 0.0009 in Model 2 (adjusted for sex and age) to 0.0000 in Model 3, which included both individual- and municipal-level variables. These findings carry significant implications for public health practice. They suggest that regional disparities in oral frailty awareness are predominantly driven by individual-level characteristics within communities, highlighting the need for targeted interventions tailored to these factors. Moreover, this study extends the current literature by demonstrating, for the first time in a nationwide sample, how municipal-level policies and programs may interact with individual characteristics to influence oral frailty awareness. This contributes important insights into the design of community-based oral health strategies.

The results of this study showed that men were less aware of oral frailty than women. This association between sex and awareness is consistent with the findings of a study conducted in one prefecture of Japan [14]. Previous research has also indicated that men are more likely than women to experience oral frailty [15], possess less oral health knowledge, engage less frequently in appropriate oral health behaviors [24], and exhibit lower levels of individual social capital [25]. These findings suggest that men may represent a particularly important target population for interventions aimed at improving awareness of oral frailty.

The age variable was significantly associated with awareness in Models 1 and 2 but not in Model 3. This finding may have occurred because age is incorporated into the estimation of oral frailty status. Indeed, when the oral frailty variable was excluded from Model 3, age became significantly associated with awareness (data not shown).

Regarding educational attainment, individuals with fewer years of education were less likely to be aware of oral frailty. This finding is consistent with previous reports indicating that educational attainment is positively associated with general oral health knowledge [26,27]. Other studies have shown that individuals with lower educational attainment are at increased risk of oral frailty [15,28]. Furthermore, the study revealed that limited oral health knowledge and unfavorable attitudes among older adults, particularly those with lower educational attainment, were associated with suboptimal oral health behaviors and an increased risk of frailty [29]. These findings highlight the need for targeted strategies designed to raise awareness of oral frailty among individuals with lower levels of educational attainment.

This study also found that individuals with oral frailty were less likely to be aware of their condition than those without. Similarly, the previous study reported a significant association between oral frailty risk and lack of awareness levels, consistent with our findings [14]. These results suggest that individuals affected by oral frailty may be insufficiently cognizant of the condition and its associated risks. Therefore, enhancing awareness among those already experiencing oral frailty is essential for its prevention and early detection.

Among the individual-level aspects of social capital, lower civic participation was associated with lack of awareness of oral frailty. Although causality cannot be inferred due to the cross-sectional design of this study, initiatives that promote civic participation may help improve awareness.

We hypothesized that awareness of oral frailty would be higher in areas with high social capital. While civic participation at the individual level was significantly associated with awareness, no such association was observed for social capital at the municipal level. Previous studies have shown that living in communities with high civic participation levels is associated with a higher risk of oral frailty [15,30], a higher number of teeth [31], and a lower risk of tooth loss [32]. Notably, these studies constructed social capital variables at the school district level. By contrast, this study assessed social capital at the municipal level because its participant sample was relatively small. The choice of geographical units used to measure social capital may have influenced the findings. Future research should use larger sample sizes and more granular geographic units.

The simple aggregation analysis on the association between awareness of oral frailty and regional factors (see Table 2) indicated that awareness tended to decrease in certain municipalities. However, the multilevel analysis (see Table 3) did not reveal a significant association at the municipal level. The previous study reported regional differences in oral frailty awareness within a secondary medical care area, which comprises several municipalities within a single prefecture [14].

Several factors may explain the differences between this study’s findings and those of the previous study [14]. First, their study used logistic regression analysis on data from eight secondary medical care areas within one prefecture, whereas this study employed a multilevel analysis of 66 municipalities across Japan. Multilevel analysis offers the advantage of enabling a study to account for both individual- and municipal-level factors simultaneously. In addition, approximately 60% of the participants resided in urban or metropolitan areas in the previous study [14], whereas 60% of the municipalities were classified as rural in this study.

No significant associations were found between awareness of oral frailty and the implementation of municipal programs, such as leaflet distribution, resident lectures, or volunteer training. The only information available about these programs was whether they were implemented. Details such as the number of residents reached were not available, making it difficult to assess their effectiveness. A review of oral health programs in 791 municipalities suggested that the presence of dental hygienists and collaboration with related organizations are key factors in the effectiveness of such programs [33]. In a survey of 248 individuals aged 20 to 80 years [34], the most commonly reported sources of information about oral frailty were mass media (e.g., television and newspapers, 47.6%), the Internet (33.1%), and explanations provided by dentists and medical institutions (14.5%).

It is essential that municipalities evaluate the effectiveness of oral frailty intervention programs by assessing the outcomes of their own initiatives and systematically collecting and sharing information on successful practices.

In the sensitivity analysis, where the response “I have heard of the term” was categorized as indicating no awareness of oral frailty, the results were largely consistent with those of the main analysis. In particular, being male, having lower educational attainment, and lacking civic participation remained significantly associated with lack of awareness. This stricter classification was used to address the possibility that participants who are only “familiar” with the term may not fully understand its implications.

This study has several limitations. First, the response rate was 67.1%, making selection bias a possibility. Second, it remains unclear to what extent participants who reported being ‘familiar’ with the term ‘oral frailty’ actually understood its meaning. It is important to assess not only familiarity with the term but also related health behaviors. Future studies should evaluate both awareness and behavior to enhance the validity of the findings. Third, the sources through which participants became informed about oral frailty remain ambiguous. Although numerous preventive programs are currently being implemented, the scope and modalities of their dissemination have not been adequately documented. Consequently, it was not possible to assess the effectiveness of specific communication channels or interventions. Identifying credible sources of information and optimizing dissemination strategies are crucial for enhancing public awareness more effectively. Fourth, the study was unable to conduct analyses at the school district level due to the limited number of respondents; therefore, the analysis was conducted at the municipal level instead. Fifth, the measurement of oral and general health status was based on self-reports rather than clinical examinations.

5. Conclusions

This study clarified the regional differences in oral frailty awareness using cross-sectional data drawn from a questionnaire survey of older adults residing in municipalities across Japan. The study sought to identify the individual- and municipal-level factors associated with awareness, focusing on the presence of dental health ordinance and the implementation of oral health programs at the municipal level. The awareness of oral frailty across 66 municipalities ranged from 15.3% to 47.1%, representing a nearly threefold difference. Individual-level factors such as sex, presence of oral frailty, civic participation, and educational attainment were significantly associated with awareness, whereas no significant associations were observed with municipal-level factors. Enhancing awareness requires that more frequent civic participation among older adults be promoted in each municipality, particularly by fostering environments that support sustained engagement in social and recreational activities among men. In addition, implementing intervention programs that communicate to residents the importance of oral frailty prevention is critical for future public health efforts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.U.A., K.I., W.S., J.A. and T.Y.; methodology, N.U.A., K.I., W.S. and T.Y.; formal analysis, N.U.A.; data curation, N.U.A. and T.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, N.U.A. and T.Y.; writing—review and editing, N.U.A., K.I., W.S., S.F., J.A. and T.Y.; visualization, N.U.A.; supervision, T.Y.; funding acquisition, J.A. and T.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study used data from the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES). The study was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (19K02200, 20H00557, 20H03954, 20K02176, 20K10540, 20K13721, 20K19534, 21H00792, 21H03196, 21K02001, 21K10323, 21K11108, 21K17302, 21K17308, 21K17322, 22H00934, 22H03299, 22J00662, 22J01409, 22K01434, 22K04450, 22K10564, 22K11101, 22K13558, 22K17265, 22K17364, 22K17409, 23K16320, 23H00449, 23H03117, 23K19793, 23K21500, 23K19796) from JSPS (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science), Health Labour Sciences Research Grants (19FA1012, 19FA2001, 21FA1012,22FA2001, 22FA1010, 22FG2001), the Research Funding for Longevity Sciences from National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (21-20), Research Institute of Science and Technology for Society (JPMJOP1831) from the Japan Science and Technology (JST), a grant from Japan Health Promotion & Fitness Foundation, contribution by Department of Active Ageing, Niigata University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences (donated by Tokamachi city, Niigata), TMDU priority research areas grant and National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Resilience. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of the respective funding organizations.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee on Research of Human Subjects at the Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine (approval no. M10460), approval date 01 November 2022, and the Kanagawa Dental University (approval no. 988), approval date 27 February 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data used are from the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES) and are not third-party data. All enquiries are to be addressed to the JAGES data management committee via e-mail: dataadmin.ml@jages.net. All JAGES datasets have ethical or legal restrictions for public deposition due to the inclusion of sensitive information from the human participants. Following the regulation of local governments which cooperated on our survey, the JAGES data management committee has imposed restrictions upon the data.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Katsunori Kondo for his valuable advice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CI | Confidence interval |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| JAGES | Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study |

| PR | Prevalence ratio |

| SE | Standard error |

References

- Murayama, H.; Kobayashi, E.; Okamoto, S.; Fukaya, T.; Ishizaki, T.; Liang, J.; Shinkai, S. National prevalence of frailty in the older Japanese population: Findings from a nationally representative survey. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 91, 104220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everaars, B.; Jerković-Ćosić, K.; Bleijenberg, N.; De Wit, N.J.; Van Der Heijden, G.J.M.G. Exploring Associations Between Oral Health and Frailty in Community-Dwelling Older People. J. Frailty Aging 2021, 10, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Takahashi, K.; Hirano, H.; Kikutani, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Ohara, Y.; Furuya, H.; Tetsuo, T.; Akishita, M.; Iijima, K. Oral Frailty as a Risk Factor for Physical Frailty and Mortality in Community-Dwelling Elderly. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2017, 73, 1661–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Dental Association. Oral Frailty Manual: Oral Frailty; 2019 edition; Japan Dental Association: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki, M.; Motokawa, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Shirobe, M.; Inagaki, H.; Edahiro, A.; Ohara, Y.; Hirano, H.; Shinkai, S.; Awata, S. Association Between Oral Frailty and Nutritional Status Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: The Takashimadaira Study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Putten, G.-J.; de Baat, C. An Overview of Systemic Health Factors Related to Rapid Oral Health Deterioration among Older People. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, H.; Kitano, Y. Oral Frailty as a Risk Factor for Fall Incidents among Community-Dwelling People. Geriatrics 2024, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwick, L.; Schmitz, N.; Shojaa, M. Oral health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms in adults: Longitudinal associations of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y.; Niu, S.; Xi, X.; Tang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yu, X.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Physical frailty intensifies the positive association of oral frailty with poor global cognitive function and executive function among older adults especially for females: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, M.; Shirobe, M.; Motokawa, K.; Tanaka, T.; Ikebe, K.; Ueda, T.; Minakuchi, S.; Akishita, M.; Arai, H.; Iijima, K.; et al. Prevalence of oral frailty and its association with dietary variety, social engagement, and physical frailty: Results from the Oral Frailty 5-Item Checklist. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2024, 24, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, S.S.; Vernon, M.; Hatzigeorgiou, C.; George, V. Health Literacy, Social Determinants of Health, and Disease Prevention and Control. J. Environ. Health Sci. 2020, 6, 3061. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Huang, S.; Song, S.; Lin, J.; Liu, F. Impact of oral health literacy on oral health behaviors and outcomes among the older adults: A scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Dental Association. Vision of Dental Care Toward 2040: Dentistry in the Reiwa Era; Japan Dental Association: Tokyo, Japan, 2020; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Irie, K.; Mochida, Y.; Altanbagana, N.U.; Fuchida, S.; Yamamoto, T. Relationship between risk of oral frailty and awareness of oral frailty among community-dwelling adults: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, T.; Mochida, Y.; Irie, K.; Altanbagana, N.U.; Fuchida, S.; Aida, J.; Takeuchi, K.; Fujita, M.; Kondo, K. Regional Inequalities in Oral Frailty and Social Capital. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2024, 9, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Dental Association. Oral Frailty Manual: Concept and Management of Oral Frailty; 2019 edition; Japan Dental Association: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Dental Association. Oral Frailty Manual: Efforts and Examples Relevant to Oral Frailty; 2019 edition; Japan Dental Association: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; pp. 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Fujihara, S.; Tsuji, T.; Miyaguni, Y.; Aida, J.; Saito, M.; Koyama, S.; Kondo, K. Does Community-Level Social Capital Predict Decline in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living? A JAGES Prospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, T.; Tanaka, T.; Hirano, H.; Mochida, Y.; Iijima, K. Model to Predict Oral Frailty Based on a Questionnaire: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, H.; Satake, S. English translation of the Kihon Checklist. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2015, 15, 518–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portal Site of Official Statistics of Japan. Municipality Data 2020. Available online: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/regional-statistics/ssdsview/municipality (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Yamada, K.; Fujii, T.; Kubota, Y.; Ikeda, T.; Hanazato, M.; Kondo, N.; Matsudaira, K.; Kondo, K. Prevalence and municipal variation in chronic musculoskeletal pain among independent older people: Data from the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES). BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Aida, J.; Kuriyama, S.; Hashimoto, H. Associations of health literacy with dental care use and oral health status in Japan. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeh, M.T. Gender Differences in Oral Health Knowledge and Practices Among Adults in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2022, 14, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Li, K.; Ogihara, A.; Wang, X. Association between social capital and depression among older adults of different genders: Evidence from Hangzhou, China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 863574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaradoss, J.K. Relationship between oral health literacy and oral health status. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Arrico, C.; Almerich-Silla, J.; Montiel-Company, J. Oral health knowledge in relation to educational level in an adult population in Spain. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2019, 11, e1143–e1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Li, X. An analysis of influencing factors of oral frailty in the elderly in the community. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, C.; Liao, S.; Cao, W.; Guo, Y.; Hong, Z.; Ren, B.; Hu, Z.; Bai, Z. Differences in the association of oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices with frailty among community-dwelling older people in China. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamid, T.A.; Salih, S.A.; Abdullah, S.F.Z.; Ibrahim, R.; Mahmud, A. Characterization of social frailty domains and related adverse health outcomes in the Asia-Pacific: A systematic literature review. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aida, J.; Hanibuchi, T.; Nakade, M.; Hirai, H.; Osaka, K.; Kondo, K. The different effects of vertical social capital and horizontal social capital on dental status: A multilevel analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, S.; Aida, J.; Saito, M.; Kondo, N.; Sato, Y.; Matsuyama, Y.; Tani, Y.; Sasaki, Y.; Kondo, K.; Ojima, T.; et al. Community social capital and tooth loss in Japanese older people: A longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Fuchida, S.; Aida, J.; Kondo, K.; Hirata, Y. Adult Oral Health Programs in Japanese Municipalities: Factors Associated with Self-Rated Effectiveness. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2015, 237, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Inamura, N.; Kaneko, T. Oral Frailty Awareness and Singing Habit-Oral Frailty Association in Japanese General Adults. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2024, 16, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).