Beyond the Unitary: Direct, Moderated, and Mediated Associations of Mindfulness Facets with Mental Health Literacy and Treatment-Seeking Attitudes

Abstract

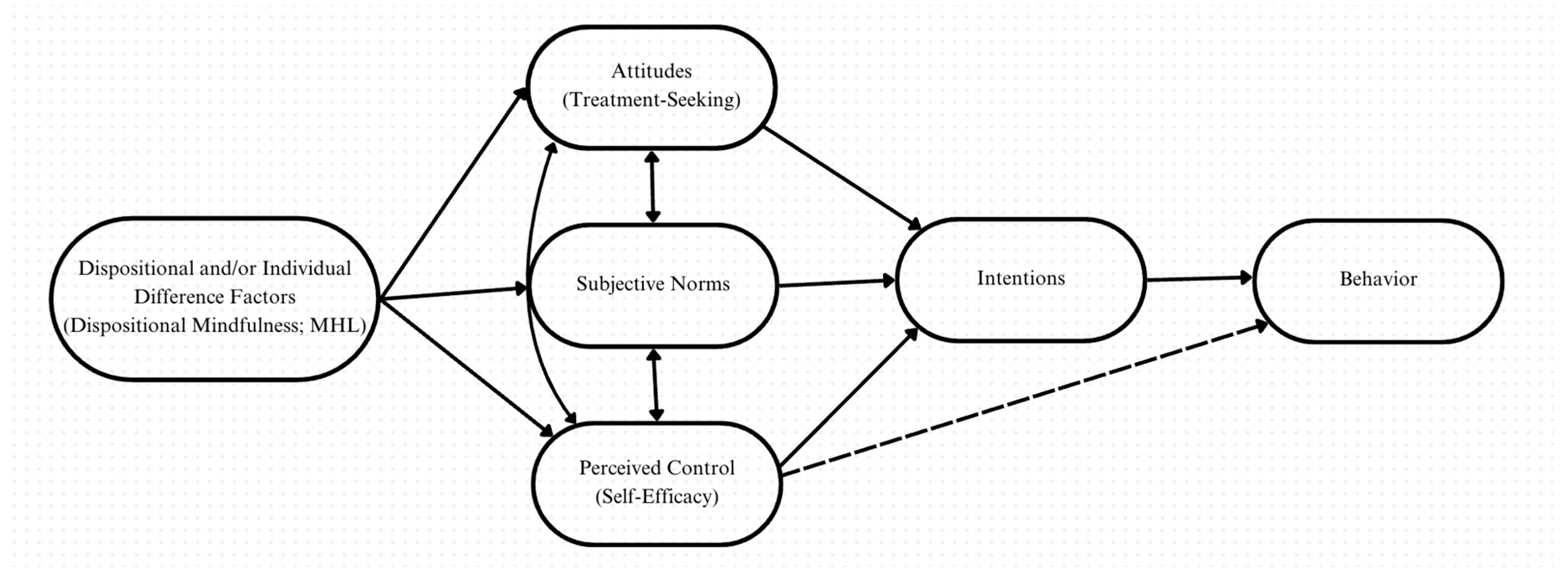

1. Introduction

2. Current Study

- All facets will exhibit moderate positive correlations with MHL, TSAs, and general self-efficacy;

- FFMQ-24’s facets of Describe, Act with Awareness, and Non-Judgment will be significant predictors of MHL over and above demographic variables;

- FFMQ-24’s facets of Observe, Describe, Act with Awareness, Non-Judgment, and Non-Reactivity will be significant predictors of TSAs over and above demographic variables;

- Describe, Act with Awareness, and Non-Judgment [33] will moderate the relationship of MHL with TSAs;

- General self-efficacy will mediate the relationships of Describe, Act with Awareness, and Non-Judgment with TSAs.

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Measures

- Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire

- Mental Health Literacy Scale

- Mental Help-Seeking Attitudes Scale

- General Self-Efficacy Scale

2.1.3. Procedure

2.2. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

Zero-Order Correlations Among Study Measures

3.2. Independent-Sample t-Tests

3.2.1. Mental Health Diagnosis

3.2.2. Prior Psychotherapy

3.2.3. Current Mindfulness Meditation Practice

3.3. Multiple Regressions

3.3.1. Mental Health Literacy Scale

3.3.2. Mental Help-Seeking Attitudes Scale

3.4. Moderation Analyses

3.5. Mediation Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographics

4.2. Facet Predictors

4.3. Facet Moderators

4.4. Facet Mediators

4.5. Practical Applications

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.-K.; Chesney, E.; Teng, W.-N.; Hollandt, S.; Pritchard, M.; Shetty, H.; Stewart, R.; McGuire, P.; Patel, R. Life Expectancy, Mortality Risks and Cause of Death in Patients with Serious Mental Illness in South East London: A Comparison between 2008–2012 and 2013–2017. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleetwood, K.J.; Guthrie, B.; Jackson, C.A.; Kelly, P.A.T.; Mercer, S.W.; Morales, D.R.; Norrie, J.D.; Smith, D.J.; Sudlow, C.; Prigge, R. Depression and Physical Multimorbidity: A Cohort Study of Physical Health Condition Accrual in UK Biobank. PLoS Med. 2025, 22, e1004532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Collins, B.; Downing, J.; Head, A.; Cornerford, T.; Nathan, R.; Barr, B. Investigating the Impact of Undiagnosed Anxiety and Depression on Health and Social Care Costs and Quality of Life: Cross-Sectional Study Using Household Health Survey Data. BJPsych Open 2023, 9, e201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Kumar, A.; Gupta, S. Mental Health Prevention and Promotion—A Narrative Review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 898009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moroz, N.; Moroz, I.; D’Angelo, M.S. Mental Health Services in Canada: Barriers and Cost-Effective Solutions to Increase Access. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2020, 33, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F. Mental Health Literacy: Public Knowledge and Beliefs about Mental Disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 177, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.; Codony, M.; Kovess, V.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Katz, S.J.; Haro, J.M.; de Girolamo, G.; de Graaf, R.; Demyttenaere, K.; Vilagut, G.; et al. Population Level of Unmet Need for Mental Healthcare in Europe. Br. J. Psychiatry 2007, 190, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Swami, V. Mental Health Literacy: A Review of What It Is and Why It Matters. Int. Perspect. Psychol. 2018, 7, 240–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, C.S.; Pankratz, L. Perceived Need, Mental Health Literacy, Neuroticism and Self-Stigma Predict Mental Health Service Use Among Older Adults. Clin. Gerontol. 2025, 48, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, C.S.; Krook, M.A.; Murphy, D.J.; Rapaport, L. Mental Health Literacy Reduces the Impact of Internalized Stigma on Older Adults’ Attitudes and Intentions to Seek Mental Health Services. Clin. Gerontol. 2024, 29, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.; Whitty, P.; Browne, S.; McTigue, O.; Kamali, M.; Gervin, M.; Kinsella, A.; Waddington, J.L.; Larkin, C.; O’Callaghan, E. Untreated Illness and Outcome of Psychosis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2006, 189, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magallón-Botaya, R.; Méndez-López, F.; Oliván-Blázquez, B.; Silva-Aycaguer, L.C.; Lerma-Irureta, D.; Bartolomé-Moreno, C. Effectiveness of Health Literacy Interventions on Anxious and Depressive Symptomatology in Primary Health Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1007238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Context: Past, Present, and Future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Carlson, L.E.; Astin, J.A.; Freedman, B. Mechanisms of Mindfulness. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 62, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The Benefits of Being Present: Mindfulness and Its Role in Psychological Well-Being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rau, H.K.; Williams, P.G. Dispositional Mindfulness: A Critical Review of Construct Validation Research. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 93, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T.; Hopkins, J.; Krietemeyer, J.; Toney, L. Using Self-Report Assessment Methods to Explore Facets of Mindfulness. Assessment 2006, 13, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshai, S.; Salimuddin, S.; Refaie, N.; Maierhoffer, J. Dispositional Mindfulness and Self-Compassion Buffer the Effects of COVID-19 Stress on Depression and Anxiety Symptoms. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 3028–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, A. The Difficulty of Defining Mindfulness: Current Thought and Critical Issues. Mindfulness 2013, 4, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlin, S.L.; Baer, R.A. Relationships between Mindfulness, Self-Control, and Psychological Functioning. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, M.M.; Mazmanian, D.; Oinonen, K.; Mushquash, C.J. Executive Function and Self-Regulation Mediate Dispositional Mindfulness and Well-Being. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 93, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Maki, A.; Montanaro, E.; Avishai-Yitshak, A.; Bryan, A.; Klein, W.M.P.; Miles, E.; Rothman, A.J. The Impact of Changing Attitudes, Norms, and Self-Efficacy on Health-Related Intentions and Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. Health Psychol. 2016, 35, 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0716728504. [Google Scholar]

- Hladek, M.D.; Gill, J.; Bandeen-Roche, K.; Walston, J.; Hinkle, J.L.; Lorig, K.; Szanton, S.L. High Coping Self-Efficacy Associated with Lower Odds of Pre-Frailty/Frailty in Older Adults with Chronic Disease. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 1956–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Potter, C.M.; Kelly, L.; Fitzpatrick, R. Self-Efficacy and Health-Related Quality of Life: A Cross-Sectional Study of Primary Care Patients with Multi-Morbidity. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giblett, A.; Hodgins, G. Flourishing or Languishing? The Relationship Between Mental Health, Health Locus of Control and Generalised Self-Efficacy. Psychol. Rep. 2023, 126, 94–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandna, S.; Sharma, P.; Moosath, H. The Mindful Self: Exploring Mindfulness in Relation with Self-Esteem and Self-Efficacy in Indian Population. Psychol. Stud. 2022, 67, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.K.; Conroy, K.; Gomez, A.F.; Curren, L.C.; Hofmann, S.G. The Relationship between Trait Mindfulness and Affective Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 74, 101785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, H.Z. Associations of Five Facets of Mindfulness With Self-Regulation in College Students. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 124, 1202–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, J.A.; Lassen, E.R.; Solem, S.; Fischer, R. Between Can’t and Won’t: The Relationship Between Trait Mindfulness, Stoic Ideology, and Alexithymia in Norway and New Zealand. Mindfulness 2024, 15, 2812–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, J.M. A Review and Critique of Emotional Intelligence Measures. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.-C.; Chen, I.-C.; Ho, W.-S.; Cheng, Y.-C. A Sequential Mediation Model of Perceived Social Support, Mindfulness, Perceived Hope, and Mental Health Literacy: An Empirical Study on Taiwanese University Students. Acta Psychol. 2023, 240, 104016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blignault, I.; Saab, H.; Woodland, L.; Mannan, H.; Kaur, A. Effectiveness of a Community-Based Group Mindfulness Program Tailored for Arabic and Bangla-Speaking Migrants. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2021, 15, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arı, Ç.; Ulun, C.; Yarayan, Y.E.; Dursun, M.; Bozkurt, T.M.; Üstün, Ü.D. Mindfulness, healthy life skills and life satisfaction in varsity athletes and university students. Prog. Nutr. 2020, 22, e2020024. [Google Scholar]

- Koç, M.S.; Uzun, R.B. Investigating the Link Between Dispositional Mindfulness, Beliefs About Emotions, Emotion Regulation and Psychological Health: A Model Testing Study. J. Ration.-Emotive Cogn.-Behav. Ther. 2024, 42, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zümbül, S.; Kağnıcı, D.Y. The Mediating Role of Mindfulness in the Relationship Between Emotional Distress Tolerance and Coping Styles in Turkish University Students. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2022, 44, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, L.H.; Alonso, J.; Mneimneh, Z.; Wells, J.E.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Borges, G.; Bromet, E.; Bruffaerts, R.; de Girolamo, G.; de Graaf, R.; et al. Barriers to Mental Health Treatment: Results from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 1303–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.J.; Spencer, S.D.; Masuda, A. Mindfulness Mediates the Relationship between Mental Health Self-Stigma and Psychological Distress: A Cross-Sectional Study. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 41, 5333–5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Yang, S.; Liu, C.; Liyan, L.; Chen, X.; Wu, F.; Huang, X. Effects of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy on Stigma in Female Patients With Schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 694575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Hwang, J.; Ball, J.G.; Lee, J.; Albright, D.L. Is Health Literacy Associated with Mental Health Literacy? Findings from Mental Health Literacy Scale. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2019, 56, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, R.; Hamer, T.; Suhr, R.; König, L. Attitudes Toward Psychotherapeutic Treatment and Health Literacy in a Large Sample of the General Population in Germany: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2025, 11, e67078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, C.; Gringart, E.; and Strobel, N. Barriers to Mental Health Help-Seeking among Older Adults with Chronic Diseases. Aust. Psychol. 2024, 59, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Shi, L.; Ying, L.; Liu, D.; Yang, J.; Hong, Y. Analysis of the mental health status and risk factors of the general population in Beijing, China: A cross-sectional study. Res. Sq. 2020; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, D. Exploring the Relationship between Social Class, Mental Illness Stigma and Mental Health Literacy Using British National Survey Data. Health 2014, 19, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziapour, A.; Azar, F.E.F.; Mahaki, B.; Mansourian, M. Factors Affecting the Health Literacy Status of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes through Demographic Variables: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2022, 11, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Hwang, J.; Ball, J.G.; Lee, J.; Yu, Y.; Albright, D.L. Mental Health Literacy Affects Mental Health Attitude: Is There a Gender Difference? Am. J. Health Behav. 2020, 44, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskar, S.; Bracic, M.F.; Kolar, U.; Lekic, K.; Juricic, N.K.; Grum, A.T.; Dobnik, B.; Postuvan, V.; Vatovec, M. Attitudes within the General Population towards Seeking Professional Help in Cases of Mental Distress. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2017, 63, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbeza, M. The Associations of Dispositional Mindfulness with the Recognition of Psychological Disorders and Willingness to Seek Help. Honours Thesis, University of Regina, Regina, SK, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Litman, L.; Robinson, J.; Abberbock, T. TurkPrime.Com: A Versatile Crowdsourcing Data Acquisition Platform for the Behavioral Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2016, 49, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Rosario, N.; Beshai, S. Do you mind? Examining the impact of psychoeducation specificity on perceptions of mindfulness-based programs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Kelley, K.; Rausch, J.R. Sample size planning for statistical power and accuracy in parameter estimation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 537–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönbrodt, F.D.; Perugini, M. At what sample size do correlations stabilize? J. Res. Personal. 2013, 47, 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlmeijer, E.; ten Klooster, P.M.; Fledderus, M.; Veehof, M.; Baer, R. Psychometric Properties of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in Depressed Adults and Development of a Short Form. Assessment 2011, 18, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, W.H.; Wang, S.; Varga, A.V.; Lim, C.X.; Xu, H.; Jarukasemthawee, S.; Pisitsungkagarn, K.; Suvanbenjakule, P.; Braden, A. Trait Mindful Nonreactivity and Nonjudgment Prospectively Predict of COVID-19 Health Protective Behaviors Across a Two-Month Interval in a USA Sample. medRxiv 2021, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M.; Casey, L. The Mental Health Literacy Scale (MHLS): A New Scale-Based Measure of Mental Health Literacy. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 229, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, J.H.; Parent, M.C.; Spiker, D.A. Mental Help Seeking Attitudes Scale (MHSAS): Development, Reliability, Validity, and Comparison with the ATSPPH-SF and IASMHS-PO. J. Couns. Psychol. 2018, 65, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, C.; Chen, S.-Y.; Yan, S.-R.; Zhao, W.-W.; Wang, R.-X.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.-H. Measurement Properties of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures of Mental Help-Seeking Attitude: A Systematic Review of Psychometric Properties. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1182670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale. In Measures in Health Psychology: A User’s Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs; Weinman, J., Wright, S., Johnston, M., Eds.; NFER-NELSON: Windsor, UK, 1995; Volume 35, p. 82-003. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1462549030. [Google Scholar]

- Chilale, H.K.; Silungwe, N.D.; Gondwe, S.; Masulani-Mwale, C. Clients and Carers Perception of Mental Illness and Factors That Influence Help-Seeking: Where They Go First and Why. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2017, 63, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, S.S.; Moshi, F.V. Factors Influencing Formal Mental Treatment—Seeking Behaviour among Caretakers of Mentally Ill Patients in Zanzibar. EA Health Res. J. 2022, 6, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, A.; Khatib, A.; Finkelstein, M. The Association between Mental Health Literacy and Resilience among Individuals Who Received Therapy and Those Who Did Not. J. Ment. Health Train. Educ. Pract. 2024, 19, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonabi, H.; Müller, M.; Ajdacic-Gross, V.; Eisele, J.; Rodgers, S.; Seifritz, E.; Rössler, W.; Rüsch, N. Mental Health Literacy, Attitudes to Help Seeking, and Perceived Need as Predictors of Mental Health Service Use: A Longitudinal Study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2016, 204, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syachroni; Rosita; Sumiarsih, M.; Nurlinawati, I.; Putranto, R.H. Prevalence and Related Factors of Common Mental Disorder Among Individual Nusantara Sehat (NSI) Staff in Remote Primary Health Care; Center of Research and Development for Health Resources and Services; Atlantis Press: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020; pp. 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ta, V.P.; Gesselman, A.N.; Perry, B.L.; Fisher, H.E.; Garcia, J.R. Stress of Singlehood: Marital Status, Domain-Specific Stress, and Anxiety in a National U.S. Sample. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 36, 461–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulsby, L.K.; Bennett, K.M. Marriage and Psychological Wellbeing: The Role of Social Support. Psychology 2015, 6, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Birmingham, W.; Jones, B.Q. Is There Something Unique about Marriage? The Relative Impact of Marital Status, Relationship Quality, and Network Social Support on Ambulatory Blood Pressure and Mental Health. Ann. Behav. Med. 2008, 35, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, J.; Dunning, D. Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 1121–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canady, B.E.; Larzo, M. Overconfidence in Managing Health Concerns: The Dunning–Kruger Effect and Health Literacy. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2023, 30, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahabi, M. The Impact of Health Communication on Health-related Decision Making. Health Educ. 2007, 107, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensukmongkol, P. Benefits of mindfulness meditation on emotional intelligence, general self-efficacy, and perceived stress: Evidence from Thailand. J. Spiritual. Ment. Health 2014, 16, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.M.C.; Dea Moore, C.; Hensing, G.; Krantz, G.; Staland-Nyman, C. General self-efficacy and its relationship to self-reported mental illness and barriers to care: A general population study. Community Ment. Health J. 2014, 50, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, J.; Cebolla, A.; Feliu-Soler, A.; Demarzo, M.M.P.; Pascual, J.C.; Baños, R.; García-Campayo, J. Relationship between meditative practice and self-reported mindfulness: The MINDSENS Composite Index. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrosiers, A.; Klemanski, D.H.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Mapping Mindfulness Facets Onto Dimensions of Anxiety and Depression. Behav. Ther. 2013, 44, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzisarantis, N.L.D.; Hagger, M.S. Mindfulness and the Intention-Behavior Relationship Within the Theory of Planned Behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 33, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhl, J.; Fuhrmann, A. Decomposing Self-Regulation and Self-Control: The Volitional Components Inventory. In Motivation and Self-Regulation Across the Life Span; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 15–49. ISBN 978-0-521-59176-8. [Google Scholar]

- Luberto, C.M.; Cotton, S.; McLeish, A.C.; Mingione, C.J.; O’Bryan, E.M. Mindfulness Skills and Emotion Regulation: The Mediating Role of Coping Self-Efficacy. Mindfulness 2013, 5, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.T. Mental health literacy and mental health status in adolescents: A population-based survey. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2014, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Sample (n) | N = 299 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | M | SD |

| 41.04 | 11.62 | |

| Gender | n | % |

| Cis woman | 148 | 49.5 |

| Cis man | 145 | 48.5 |

| Other | 6 | 2.0 |

| Ethnicity | n | % |

| Black | 25 | 8.4 |

| East Asian | 11 | 3.7 |

| Latinx | 14 | 4.7 |

| Middle Eastern | 1 | 0.3 |

| Southeast Asian | 10 | 3.3 |

| White | 231 | 77.3 |

| Other racial categories | 6 | 2.0 |

| Marital Status | n | % |

| Single, never married | 123 | 41.1 |

| Married | 136 | 45.5 |

| Separated/Divorced | 35 | 11.7 |

| Widowed | 5 | 1.7 |

| Children | n | % |

| Yes | 144 | 48.2 |

| No | 154 | 51.5 |

| Approximate Annual Income (CAD) | n | % |

| Unemployed/No yearly income | 13 | 4.3 |

| 10,000–30,000 | 84 | 28.1 |

| 31,000–50,000 | 66 | 22.1 |

| 51,000–75,000 | 59 | 19.7 |

| 76,000–99,000 | 40 | 13.4 |

| 100,000 and over | 34 | 11.4 |

| Other | 3 | 1.0 |

| Highest Level of Education | n | % |

| No degree, certificate, or diploma | 5 | 1.7 |

| Secondary (high) school diploma or equivalent | 60 | 20.1 |

| Trades certificate or diploma | 14 | 4.7 |

| Other non-university certificate or diploma | 14 | 4.7 |

| University certificate or diploma below bachelor level | 28 | 9.4 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 121 | 40.5 |

| Master’s degree | 45 | 15.1 |

| Doctorate | 6 | 2.0 |

| Other | 6 | 2.0 |

| Religion/Belief System | n | % |

| Christianity | 157 | 52.5 |

| Atheism | 50 | 16.7 |

| Agnosticism | 61 | 20.4 |

| Other | 31 | 10.4 |

| First Language | n | % |

| English | 294 | 98.3 |

| Other | 5 | 1.7 |

| Prior Mental Illness Diagnosis | n | % |

| Yes, please specify | 94 | 31.4 |

| No | 192 | 64.2 |

| Prefer not to disclose | 13 | 4.3 |

| Prior Psychotherapy | n | % |

| Yes | 80 | 26.8 |

| No | 207 | 69.2 |

| Prefer not to disclose | 12 | 4.0 |

| Mindfulness/Mindfulness-Based Intervention Knowledge (0–10 scale) | n | % |

| 0 | 15 | 5.0 |

| 1 | 40 | 13.4 |

| 2 | 29 | 9.7 |

| 3 | 26 | 8.7 |

| 4 | 23 | 7.7 |

| 5 | 41 | 13.7 |

| 6 | 36 | 12.0 |

| 7 | 36 | 12.0 |

| 8 | 23 | 7.7 |

| 9 | 9 | 3.0 |

| 10 | 21 | 7.0 |

| Prior Mindfulness-Based Intervention Participation | n | % |

| Yes | 49 | 16.4 |

| No | 244 | 81.6 |

| Prefer not to disclose | 6 | 2.0 |

| Current Mindfulness Practices | n | % |

| Yes | 85 | 28.4 |

| No | 210 | 70.2 |

| Prefer not to disclose | 4 | 1.3 |

| Current Anti-Depressant Medication | n | % |

| Yes | 43 | 14.4 |

| No | 254 | 84.9 |

| Prefer not to disclose | 2 | 0.7 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. OB | 1.0 | - | ||||||

| 2. DS | 0.33 ** | 1.0 | - | |||||

| 3. AA | 0.17 ** | 0.50 ** | 1.0 | - | ||||

| 4. NJ | −0.01 | 0.43 ** | 0.51 ** | 1.0 | - | |||

| 5. NR | 0.20 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.30 ** | 1.0 | - | ||

| 6. MHLS | 0.08 | 0.17 ** | 0.13 * | 0.12 * | −0.07 | 1.0 | - | |

| 7. MHSAS | 0.13 * | 0.18 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.14 * | 0.16 ** | 0.37 ** | 1.0 | - |

| 8. GSES | 0.24 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.20 ** | 1.0 |

| OB | N | M | SD | F | Sig | t | df | p | Lower | Upper | D |

| Yes | 94 | 14.98 | 3.18 | −0.05 | |||||||

| No | 192 | 15.14 | 3.28 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 0.889 | 0.347 | −0.396 | 284 | 0.692 | −0.97 | 0.64 | ||||

| DS | −0.17 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 94 | 17.36 | 4.76 | ||||||||

| No | 192 | 18.12 | 4.28 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 3.031 | 0.083 | −1.356 | 284 | 0.176 | −1.86 | 0.34 | ||||

| AA | −0.34 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 94 | 16.63 | 4.44 | ||||||||

| No | 192 | 18.18 | 4.71 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 1.145 | 0.286 | −2.663 | 284 | 0.008 ** | −2.69 | −0.40 | ||||

| NJ | −0.18 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 94 | 15.27 | 4.84 | ||||||||

| No | 192 | 16.14 | 4.78 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 0.000 | 0.993 | −1.440 | 284 | 0.151 | −2.06 | 0.32 | ||||

| NR | −0.58 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 94 | 14.56 | 4.76 | ||||||||

| No | 192 | 17.04 | 3.97 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Not Assumed | 5.046 | 0.025 * | −4.354 | 158.243 | <0.001 ** | −3.59 | −1.35 | ||||

| MHSAS | 0.17 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 94 | 49.80 | 10.76 | ||||||||

| No | 192 | 47.92 | 11.57 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 4.018 | 0.046 | 1.318 | 284 | 0.189 | −0.93 | 4.68 | ||||

| GSES | −0.47 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 94 | 28.17 | 5.96 | ||||||||

| No | 192 | 30.72 | 5.26 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 0.640 | 0.425 | −3.691 | 284 | <0.001 ** | −3.92 | −1.19 | ||||

| MHLS | 0.82 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 94 | 131.41 | 11.91 | ||||||||

| No | 192 | 118.80 | 16.78 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Not Assumed | 14.924 | <0.001 ** | 7.316 | 247.700 | <0.001 ** | 9.22 | 16.02 |

| Observe | N | M | SD | F | Sig | t | df | p | Lower | Upper | d |

| Yes | 80 | 15.41 | 3.19 | 0.14 | |||||||

| No | 207 | 14.97 | 3.27 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 0.003 | 0.953 | 1.032 | 285 | 0.303 | −0.40 | 1.28 | ||||

| Describe | 0.27 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 80 | 18.70 | 4.40 | ||||||||

| No | 207 | 17.52 | 4.45 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 0.002 | 0.964 | 2.017 | 285 | 0.045 | 0.03 | 2.33 | ||||

| Act with Awareness | 0.07 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 80 | 17.86 | 4.47 | ||||||||

| No | 207 | 17.55 | 4.76 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 0.906 | 0.342 | 0.506 | 285 | 0.614 | −0.90 | 1.53 | ||||

| Non-Judgment | 0.06 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 80 | 16.05 | 5.14 | ||||||||

| No | 207 | 15.75 | 4.68 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 1.435 | 0.232 | 0.475 | 285 | 0.635 | −0.95 | 1.55 | ||||

| Non-Reactivity | −0.19 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 80 | 15.60 | 4.60 | ||||||||

| No | 207 | 16.43 | 4.30 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 0.388 | 0.534 | −1.438 | 285 | 0.151 | −1.97 | 0.31 | ||||

| MHSAS | 0.28 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 80 | 50.63 | 10.33 | ||||||||

| No | 207 | 47.51 | 11.61 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Not Assumed | 4.765 | 0.03 * | 2.213 | 160.242 | 0.036 * | 0.20 | 6.04 | ||||

| GSES | −0.025 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 80 | 29.75 | 5.50 | ||||||||

| No | 207 | 29.89 | 5.67 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 0.089 | 0.765 | −0.188 | 285 | 0.851 | −1.60 | 1.32 | ||||

| MHLS | 0.99 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 80 | 133.65 | 11.09 | ||||||||

| No | 207 | 118.76 | 16.34 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Not Assumed | 16.336 | <0.001 ** | 8.857 | 210.44 | <0.001 ** | 10.99 | 18.80 |

| Observe | N | M | SD | F | Sig | t | df | p | Lower | Upper | d |

| Yes | 85 | 16.24 | 2.68 | 0.50 | |||||||

| No | 210 | 14.65 | 3.33 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 3.427 | 0.065 | 3.904 | 293 | <0.001 ** | 0.78 | 2.38 | ||||

| Describe | 0.03 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 85 | 17.95 | 4.37 | ||||||||

| No | 210 | 17.81 | 4.51 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 0.292 | 0.589 | 0.250 | 293 | 0.803 | −0.99 | 1.27 | ||||

| Act with Awareness | −0.10 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 85 | 17.32 | 4.60 | ||||||||

| No | 210 | 17.8 | 4.66 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 0.045 | 0.832 | −0.807 | 293 | 0.420 | −1.66 | 0.69 | ||||

| Non-Judgment | 0.04 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 85 | 15.96 | 4.90 | ||||||||

| No | 210 | 15.76 | 4.83 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 0.038 | 0.845 | 0.333 | 293 | 0.739 | −1.02 | 1.43 | ||||

| Non-Reactivity | 0.13 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 85 | 16.54 | 4.20 | ||||||||

| No | 210 | 15.97 | 4.52 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 1.496 | 0.222 | 1.008 | 293 | 0.314 | −0.55 | 1.70 | ||||

| MHSAS | −0.02 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 85 | 48.29 | 10.50 | ||||||||

| No | 210 | 48.50 | 11.82 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 0.441 | 0.507 | −0.143 | 293 | 0.886 | −3.11 | 2.69 | ||||

| GSES | 0.19 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 85 | 30.52 | 5.05 | ||||||||

| No | 210 | 29.44 | 5.88 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Assumed | 1.142 | 0.286 | 1.478 | 293 | 0.141 | −0.36 | 2.51 | ||||

| MHLS | −0.35 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 85 | 118.92 | 18.77 | ||||||||

| No | 210 | 124.58 | 15.03 | ||||||||

| Equal Variances Not Assumed | 9.163 | 0.003 ** | −2.476 | 129.752 | 0.015 * | −10.18 | −1.14 |

| B | SE B | β | t | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (Demographics): R = 0.34, R2 = 0.11, F for change in R2 = 6.97 ** | |||||

| Constant | 116.20 | 4.12 | 28.21 | ||

| Age | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.17 ** | 3.10 | |

| Women ref | 3.43 | 1.86 | 0.11 | 1.84 | |

| Married | −6.82 | 2.08 | −0.21 ** | −3.28 | |

| Education | −1.28 | 0.43 | −0.19 ** | −3.01 | |

| Yearly Income | 1.45 | 0.73 | 0.13 * | 2.00 | |

| Model 2 (Demographics and Predicting Factors): R = 0.38, R2 = 0.14, ΔR2 = 0.04, F for change in R2 = 2.39 * | |||||

| Constant | 112.00 | 6.46 | 17.3 | ||

| Age | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.15 ** | 2.58 | |

| Women ref | 2.38 | 1.88 | 0.07 | 1.26 | |

| Married | −6.85 | 2.09 | −0.21 ** | −3.27 | |

| Education | −1.19 | 0.43 | −0.17 ** | −2.78 | |

| Yearly Income | 1.39 | 0.73 | 0.13 | 1.92 | |

| OB | 0.18 | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.59 | |

| DS | 0.55 | 0.26 | 0.15 * | 2.09 | |

| AA | −0.05 | 0.25 | −0.02 | −0.21 | |

| NJ | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.89 | |

| NR | −0.57 | 0.23 | −0.15 * | −2.51 | |

| B | SE B | β | t | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (Demographics): R = 0.12, R2 = 0.01, F for change in R2 = 0.85 | |||||

| Constant | 43.09 | 3.02 | 14.28 | ||

| Age | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 1.24 | |

| Women ref | 1.25 | 1.36 | 0.06 | 0.92 | |

| Married | 0.07 | 1.52 | 0.00 | 0.05 | |

| Education | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.06 | 0.86 | |

| Yearly Income | 0.08 | 0.53 | 0.01 | 0.16 | |

| Model 2 (Demographics and Predicting Factors): R = 0.30, R2 = 0.09, ΔR2 = 0.07, F for change in R2 = 4.67 ** | |||||

| Constant | 28.18 | 4.64 | 6.07 | ||

| Age | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.03 | |

| Women ref | 1.75 | 1.35 | 0.08 | 1.29 | |

| Married | 0.66 | 1.50 | 0.03 | 0.44 | |

| Education | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.09 | 1.44 | |

| Yearly Income | −0.21 | 0.52 | −0.03 | −0.41 | |

| OB | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.90 | |

| DS | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.38 | |

| AA | 0.52 | 0.18 | 0.21 ** | 2.92 | |

| NJ | −0.03 | 0.17 | −0.01 | −0.15 | |

| NR | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 1.63 | |

| Facet (W/Moderator) | R2 (Model) | b (Interaction) | SE (Interaction | p (Interaction) | ΔR2 (Interaction) | X→Y at Low W (b, p) | X→Y at Mean W (b, p) | X→Y at High W (b, p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OB | 0.15 * | −0.0169 | 0.0114 | 0.138 | 0.0064 | Not provided | Not provided | Not provided |

| DS | 0.16 * | 0.0124 | 0.0093 | 0.1865 | 0.005 | Not provided | Not provided | Not provided |

| AA | 0.18 * | 0.0163 | 0.0080 | 0.044 | 0.0114 | 0.1766 (p = 0.0003) | 0.2518 (p < 0.0001) | 0.3271 (p < 0.0001) |

| NJ | 0.15 * | 0.0063 | 0.0079 | 0.795 | 0.4273 | Not provided | Not provided | Not provided |

| NR | 0.19 * | 0.0237 * | 0.0237 | 0.007 * | 0.0205 | 0.1638 (p = 0.0018) | 0.2684 (p < 0.001) | 0.3730 (p < 0.001) |

| Facet (Predictor) | a (X→M) | b (M→Y) | c (Total) | c′ (Total) | Indirect Effect | 99% CI (Indirect) | p (Mediation Sig at 0.01) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OB | 0.4144 ** | 0.3605 ** | 0.4421 (p = 0.03) * | 0.2927 (p = 0.16) | 0.1494 | [0.0033, 0.3848] | Yes |

| DS | 0.6320 ** | 0.2862 | 0.4692 ** | 0.2884 | 0.1809 | [−0.0542, 0.4634] | No |

| AA | 0.3622 ** | 0.2856 | 0.5715 ** | 0.4680 ** | 0.1034 | [−0.0121, 0.2665] | No |

| NJ | 0.2840 ** | 0.3530 ** | 0.3270 (p = 0.0168) * | 0.2268 (p = 0.1022) | 0.1002 | [0.0088, 0.2305] | Yes |

| NR | 0.7211 ** | 0.3170 | 0.4165 ** | 0.1879 | 0.2286 | [–0.0486, 0.4990] | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gerbeza, M.; Dąbek, K.; Lockinger, K.; Wilkens, I.M.; Loarca-Rodriguez, M.; Grogan, K.; Beshai, S. Beyond the Unitary: Direct, Moderated, and Mediated Associations of Mindfulness Facets with Mental Health Literacy and Treatment-Seeking Attitudes. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101201

Gerbeza M, Dąbek K, Lockinger K, Wilkens IM, Loarca-Rodriguez M, Grogan K, Beshai S. Beyond the Unitary: Direct, Moderated, and Mediated Associations of Mindfulness Facets with Mental Health Literacy and Treatment-Seeking Attitudes. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101201

Chicago/Turabian StyleGerbeza, Matea, Kelsy Dąbek, Katelyn Lockinger, Isabelle M. Wilkens, Mia Loarca-Rodriguez, Katimah Grogan, and Shadi Beshai. 2025. "Beyond the Unitary: Direct, Moderated, and Mediated Associations of Mindfulness Facets with Mental Health Literacy and Treatment-Seeking Attitudes" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101201

APA StyleGerbeza, M., Dąbek, K., Lockinger, K., Wilkens, I. M., Loarca-Rodriguez, M., Grogan, K., & Beshai, S. (2025). Beyond the Unitary: Direct, Moderated, and Mediated Associations of Mindfulness Facets with Mental Health Literacy and Treatment-Seeking Attitudes. Healthcare, 13(10), 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101201