How to Promote the Idea of Transplantation—Second Life Social Campaign as an Example of Successful Action in Poland—What Youth Is Used to, Adults Remember

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Transplant Landscape in the Country

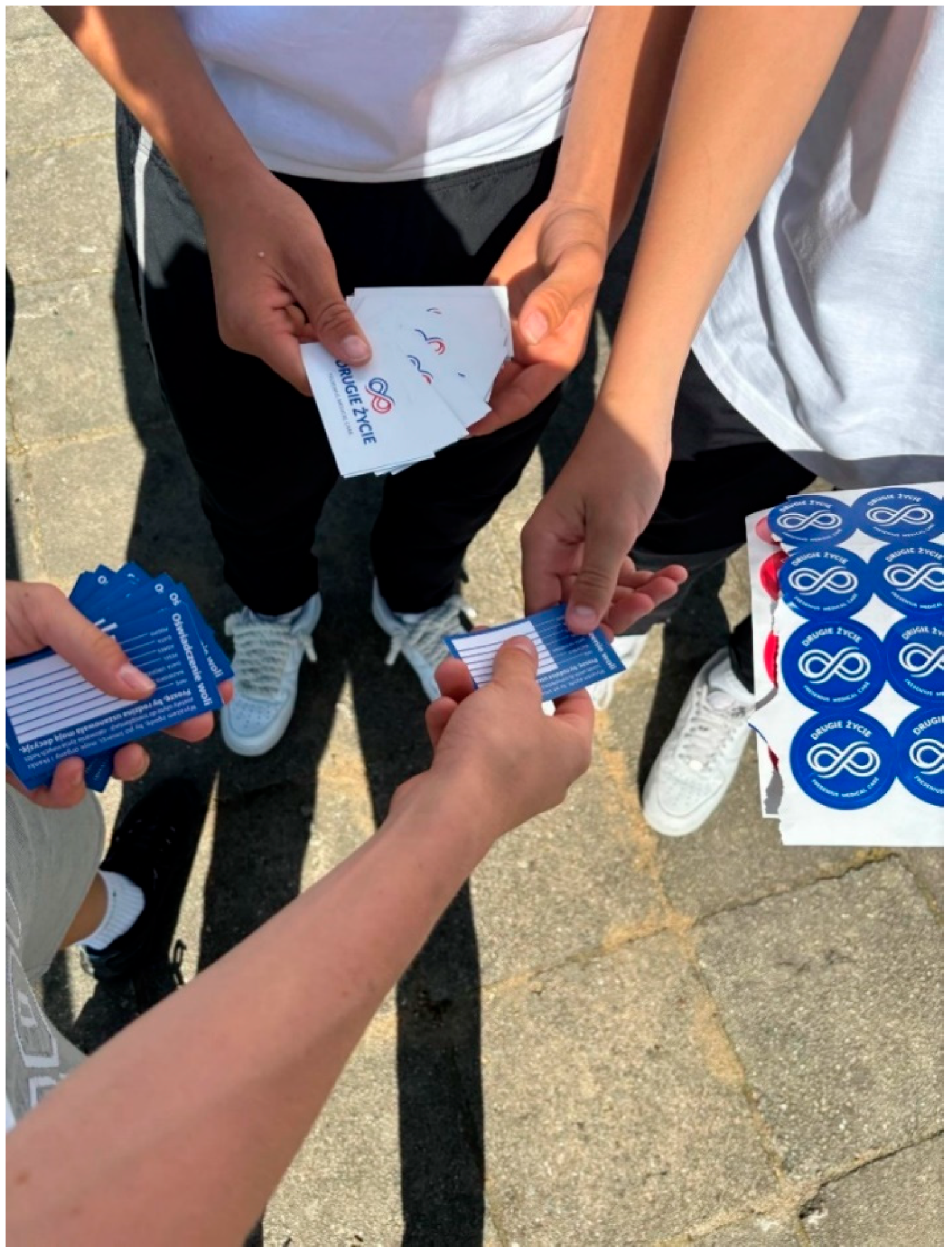

3. The Idea of Campaign

4. How It Works

5. Second Life Social Campaign in Numbers

6. Discussion

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Report on Organ Donation and Transplantation Activities 2022. Global Access to Transplantation. Available online: https://www.transplant-observatory.org/ (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Poltransplant Bulletin 2024. Biuletyn Informacyjny Poltransplantu. Available online: www.poltransplant.org.pl (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Henderson, M.L.; Clayville, K.A.; Fisher, J.S.; Kuntz, K.K.; Mysel, H.; Purnell, T.S.; Schaffer, R.L.; Sherman, L.A.; Willock, E.P.; Gordon, E.J. Social media and organ donation. Ethically navigating the next frontier. Am. J. Transplant. 2017, 17, 2803–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeziński, M.; Klikowicz, P. Facebook as a medium for promoting statement of intent for organ donation: 5-years of experience. Ann. Transplant. 2015, 20, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aykas, A.; Uslu, A.; Şimşek, C. Mass media, online social network, and organ donation: Old mistakes and new perspectives. Transplant. Proc. 2015, 47, 1070–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Jiang, W.; Cai, J.; Su, Q.; Zhou, Z.; He, L.; Lai, K. Characterizing Media Content and Effects of Organ Donation on a Social Media Platform: Content Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malanowski, P.; Czerwiński, J.; Gościniak, M.; Szemis, Ł.; Kamiński, A. Non-Donor Registry in Poland: Poltransplant Activity. Transplant. Proc. 2022, 54, 848–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attitude to Organ Transplantation. Polish Public Opinion 2016. Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/PL/publikacje/public_opinion/2016/08_2016.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Wyjątkowy Mural w Poznańskim Szpitalu! Promuje Temat Transplantacji. Zobacz Zdjęcia!|Głos Wielkopolski. Available online: https://gloswielkopolski.pl/wyjatkowy-mural-w-poznanskim-szpitalu-promuje-temat-transplantacji-zobacz-zdjecia/ar/c1-18262171 (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Boratyński, W.; Bączek, G.; Dyzmann-Sroka, A.; Jędrzejczak, A.; Kielan, A.; Mularczyk-Tomczewska, P.; Nowak, E.; Steć, M.; Szynkiewicz, M. University Students vs. Lay People’s Perspectives on Organ Donation and Improving Healthcare Communication in Poland. Ethics Prog. 2018, 9, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurleto, P.; Tomaszek, L.; Milaniak, I.; Bramstedt, K.A. Polish attitudes towards unspecified kidney donation: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2022, 23, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, E.; Pfitzner, R.; Koźlik, P.; Kozynacka, A.; Durajski, Ł.; Przybyłowski, P. Current State of Knowledge, Beliefs, and Attitudes Toward Organ Transplantation Among Academic Students in Poland and the Potential Means for Altering Them. Transplant. Proc. 2014, 46, 2509–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantarovich, F. Education and Organ Donation. Potential Role of School Programs: Abstract# C2087. Transplantation 2014, 98, 838. [Google Scholar]

- Siebelink, M.J.; Verhagen, A.A.E.; Roodbol, P.F.; Albers, M.J.I.J.; Van de Wiel, H.B.M. Education on organ donation and transplantation in primary school; teachers’ support and the first results of a teaching module. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M.; Stainer, B.; Symington, M.; Leighton, J.; Jackson, H.; Singhal, N.; Patel, S.; Shiel-Rankin, S.; Mayes, J.; Mogg, J.; et al. School education to increase organ donation and awareness of issues in transplantation in the UK. Pediatr. Transplant. 2019, 23, e13492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantarovich, F.; Cantarovich, M.; Falco, E.; Revello, R.; Legendre, C.; Herrera-Gayol, A. Education on organ donation and transplantation in elementary and high schools: Formulation of a new proposal. Transplantation 2010, 89, 1167–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantarovich, F.; Heguilén, R.; Filho, M.A.; Duro-Garcia, V.; Fitzgerald, R.; Mayrhofer-Reinhartshuber, D.; Lavitrano, M.-L.; Esnault, V.L.M. An international opinion poll of well-educated people regarding awareness and feelings about organ donation for transplantation. Transpl. Int. 2007, 20, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydzewska, M.; Drobek, N.; Małyszko, M.; Zajkowska, A.; Malyszko, J. Opinions and Attitudes of Medical Students About Organ Donation and Transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2018, 50, 1939–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydzewska, M.; Drobek, N.; Małyszko, M.; Zajkowska, A.; Guzik-Makaruk, E.; Pływaczewski, E.; Malyszko, J. Future Lawyers Support Organ Donation and Transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2018, 50, 1946–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mąkosa, P.; Olszyńska, A.; Petryszyn, K.; Kozłowska, H.; Tomszys, E.; Stoltmann, A.; Małyszko, J. Organ Procurement in Poland: Legal and Medical Aspects. Transplant. Proc. 2020, 52, 2015–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mąkosa, P.; Olszyńska, A.; Guzik-Makaruk, E.; Plywaczewski, E.; Małyszko, J. Knowledge of Law Students on the Problems of Modern Transplantology Is Good but It Can Always Be Better. Transplant. Proc. 2020, 52, 1985–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobus, G.; Reszec, P.; Malyszko, J. Opinions and Attitudes of University Students Concerning Organ Transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2016, 48, 1360–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobus, G.; Malyszko, J.S.; Małyszko, J. Do Age and Religion Have an Impact on the Attitude to Organ Transplantation? Transplant. Proc. 2016, 48, 1354–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobus, G.; Bachórzewska-Gajewska, H.; Małyszko, J. Do Muslims Living in Poland Approve of Organ Transplantation? Ann. Transplant. 2022, 27, e934494-1–e934494-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobus, G.; Małyszko, J.; Bachórzewska-Gajewska, H. Opinions of Followers of Judaism Residing in the Northeastern Part of Poland on Organ Donation. Transplant. Proc. 2020, 52, 2895–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobus, G.; Piotrowska, J.; Malyszko, J.; Bachorzewska-Gajewska, H.; Malyszko, J. Attitudes of members of the Baptist Church toward organ transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2014, 46, 2487–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobus, G.; Popławska, W.; Zbroch, E.; Małyszko, J.; Bachórzewska-Gajewska, H.; Małyszko, J. Opinions of town residents on organ transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2014, 46, 2492–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobus, G.; Popławska, B.; Bachórzewska-Gajewska, H.; Małyszko, J.S.; Małyszko, J. Opinions and knowledge about organ donation and transplantation of residents of selected villages in Podlaskie Voivodeship. Ann. Transplant. 2015, 20, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupic, F.; Grbic, K.; Senorski, E.; Lepara, Z.; Jasarevic, A.; Custovic, S.; Lindström, P. Young people’s views of organ donation and transplantation as seen by high-school and university students in Sweden. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2020, 10, 287–296. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, C.; Salim, A.; Ley, E.J.; Schulman, D.; Anderson, J.; Navarro, S.; Zheng, L.; Chan, L.S. Organ donation and Hispanic american high school students: Attitudes, beliefs, perceptions, and intent to donate. Am. Surg. 2012, 78, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, A.; Berry, C.; Ley, E.J.; Schulman, D.; Navarro, S.; Chan, L.S. Utilizing the media to help increase organ donation in the Hispanic American population. Clin. Transplant. 2011, 25, E622–E628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitkopf, C.R. Attitudes, beliefs and behaviors surrounding organ donation among Hispanic women. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 2009, 14, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salim, A.; Ley, E.J.; Berry, C.; Schulman, D.; Navarro, S.; Zheng, L.; Chan, L.S. Increasing organ donation in Hispanic Americans: The role of media and other community outreach efforts. JAMA Surg. 2014, 149, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, A.; Bery, C.; Ley, E.J.; Schulman, D.; Navarro, S.; Zheng, L.; Chan, L.S. A focused educational program after religious services to improve organ donation in Hispanic Americans. Clin. Transplant. 2012, 26, E634–E640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loban, K.; Wong-Mersereau, C.; Ferrer, J.C.; Hales, L.; Przybylak-Brouillard, A.; Cantarovich, M.; Kute, V.B.; Bhalla, A.K.; Morgan, R.; Sandal, S. Systemic Factors Contributing to Gender Differences in Living Kidney Donation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis Using the Social-Ecological Model Lens. Am. J. Nephrol. 2025, 56, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Gayol, A.; Cantarovich, M. Connecting D.O.T.S.: An Education on an Organ Donation and Transplantation Program for Schools. Exp. Clin. Transplant. 2024, 22 (Suppl. S5), 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenaart, E.; Crutzen, R.; de Vries, N.K. Implementation of an interactive organ donation education program for Dutch lower-educated students: A process evaluation. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krucińska, B.; Pendraszewska, M.; Wyzgał, J.; Czyżewski, Ł. Assessment of Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Transplantation Among Nursing Students. Transplant. Proc. 2020, 52, 1991–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, N.; Bayraktar, Ü. A cross-sectional study of university students’ awareness, knowledge, and attitudes on organ donation and transplantation in Northern Cyprus. Medicine 2024, 103, e38701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsacher, A.; Bade, C.; Ehlers, J.; Fehring, L. How to effectively communicate health information on social media depending on the audience’s personality traits: An experimental study in the context of organ donation in Germany. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 335, 116226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samin, Y.; Durrani, T.; Yousaf, A.; Majid, M.; Misbah, D.; Zahoor, M.; Khan, M.A. Barriers and Enablers to Joining the National Organ Donation Registry Among Patient Population at a Tertiary Care Hospital of Peshawar, Pakistan. Cureus 2023, 15, e37997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tattoli, L.; Santovito, D.; Raciti, I.M.; Scarmozzino, A.; Di Vella, G. Risk Assessment and Management for Potential Living Kidney Donors: The Role of “Third-Party” Commission. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 824048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonajilin, M.S.; Banik, R.; Islam, M.S.; Ishadi, K.S.; Hosen, I.; Gesesew, H.A.; Ward, P.R. Understanding the Public’s Viewpoint on Organ Donation Among Adults in Bangladesh: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e70254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, A.; López-Gómez, S.; Belmonte, J.; Balaguer, A.; Gutiérrez, P.R.; Ruiz-Merino, G.; Ayala-García, M.A.; Ramírez, P.; López-Navas, A.I. The Roma population’s fear of donating their own organs for transplantation. Cir. Esp. 2023, 101, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, A.; López-Gómez, S.; Belmonte, J.; López-Navas, A.; Sánchez, A.; Carrillo, J.; Ruiz-Manzanera, J.; Hernández, A.; Ramírez, P.; Parrilla, P. Gypsy Population Presents a Favorable Attitude Toward Related Living Donation. Transplant. Proc. 2019, 51, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiński, A.; Bury, M.; Rozenek, H.; Banasiewicz, J.; Wójtowicz, S.; Owczarek, K. Work-related problems faced by coordinators of organ, cell, and tissue transplantations in Poland and possible ways of ameliorating them. Cell Tissue Bank. 2022, 23, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zawierucha, J.; Piasecka, J.; Patelka, A.; Malyszko, J.; Małyszko, J. 446.8: Second life social campaign as a method for SOT donors pool increase—16 years of experience in Poland. Transplantation 2024, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://poltransplant.org.pl/statystyka-2025/statystyka-2024/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

| Date | Activity |

|---|---|

| September |

|

| October–November |

|

| November–May |

Space for students’ actions, e.g.,:

|

| June |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zawierucha, J.; Piasecka, J.; Patelka, A.; Małyszko, S.J.; Małyszko, J.S.; Małyszko, J. How to Promote the Idea of Transplantation—Second Life Social Campaign as an Example of Successful Action in Poland—What Youth Is Used to, Adults Remember. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101203

Zawierucha J, Piasecka J, Patelka A, Małyszko SJ, Małyszko JS, Małyszko J. How to Promote the Idea of Transplantation—Second Life Social Campaign as an Example of Successful Action in Poland—What Youth Is Used to, Adults Remember. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101203

Chicago/Turabian StyleZawierucha, Jacek, Julia Piasecka, Agnieszka Patelka, Sławomir Jerzy Małyszko, Jacek Stanisław Małyszko, and Jolanta Małyszko. 2025. "How to Promote the Idea of Transplantation—Second Life Social Campaign as an Example of Successful Action in Poland—What Youth Is Used to, Adults Remember" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101203

APA StyleZawierucha, J., Piasecka, J., Patelka, A., Małyszko, S. J., Małyszko, J. S., & Małyszko, J. (2025). How to Promote the Idea of Transplantation—Second Life Social Campaign as an Example of Successful Action in Poland—What Youth Is Used to, Adults Remember. Healthcare, 13(10), 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101203