Mental Health of Czech University Psychology Students: Negative Mental Health Attitudes, Mental Health Shame and Self-Compassion

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Negative Mental Health Attitudes and Shame

1.2. Self-Compassion

1.3. Mental Health and Emotion Regulation

1.4. Aims and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Correlations (H1)

3.2. Regression (H2)

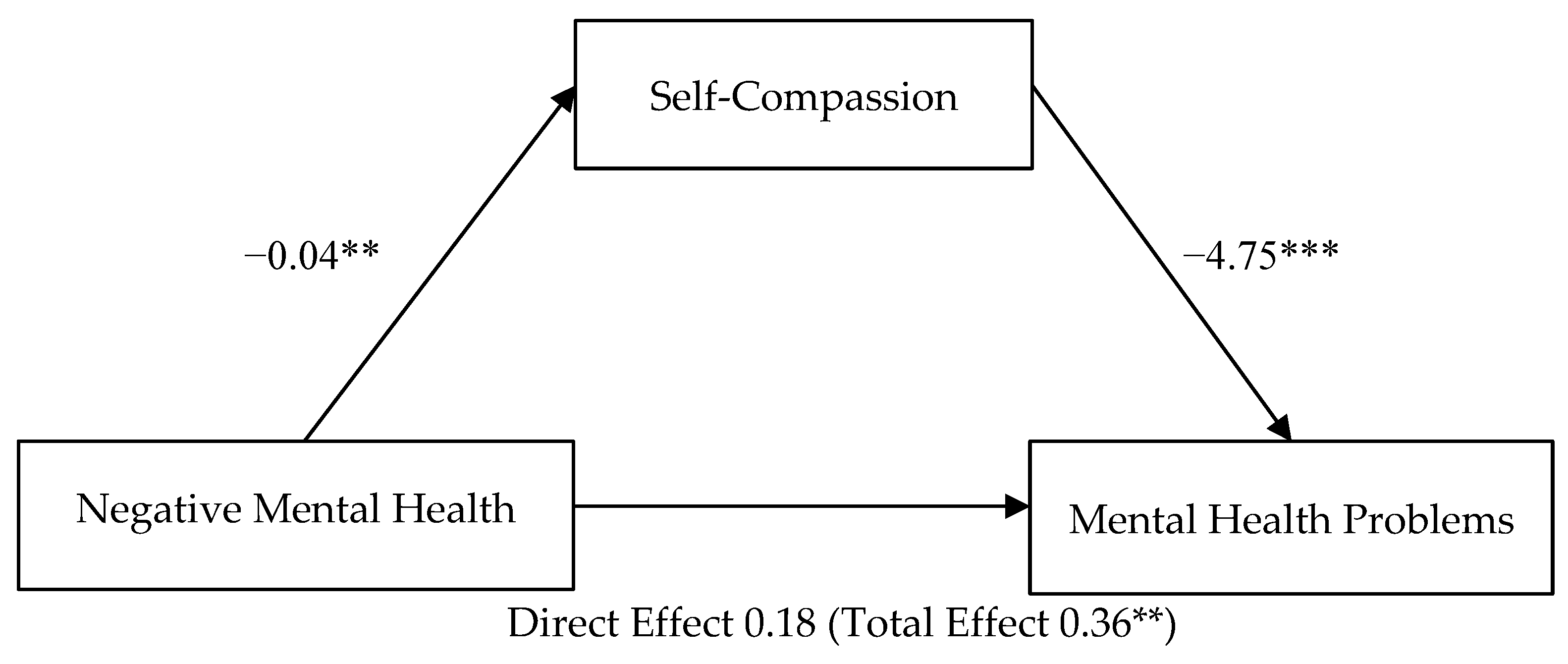

3.3. Mediation of Self-Compassion on Negative Mental Health Attitudes—Mental Health Problems (H3)

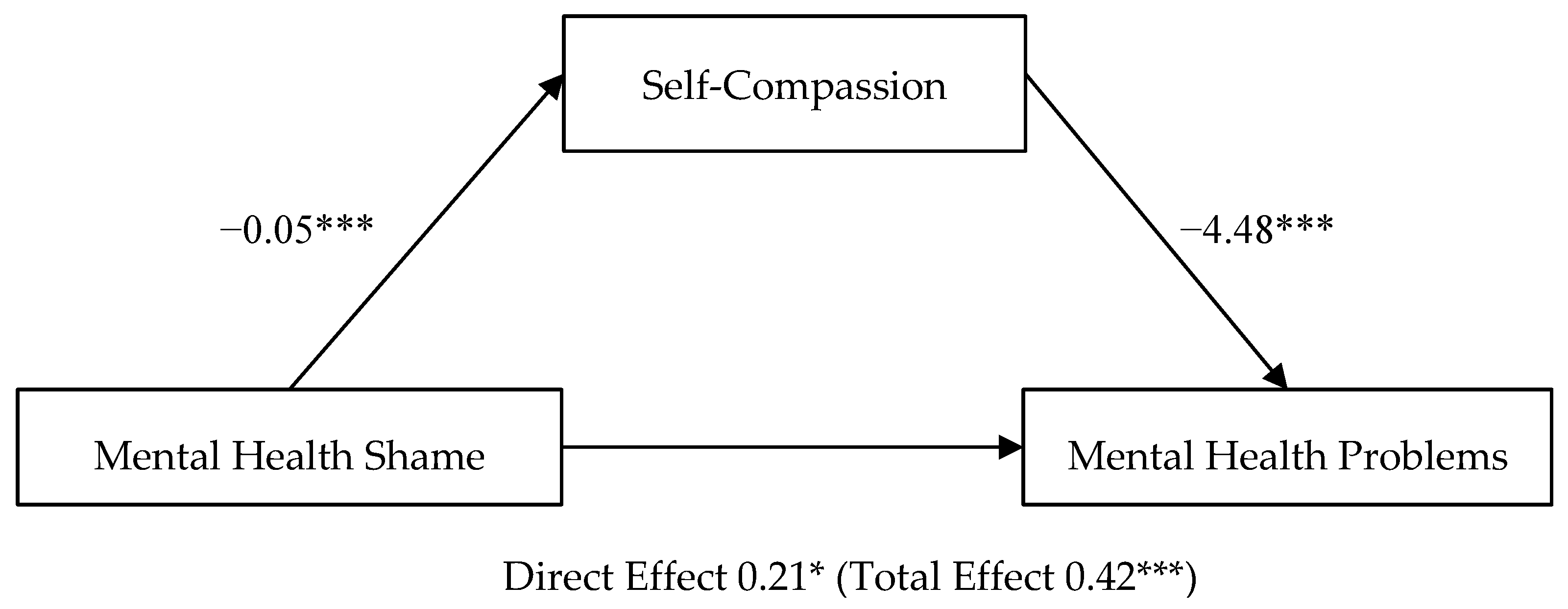

3.4. Mediation of Self-Compassion on Mental Health Shame—Mental Health Problems (H4)

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raikhel, E.; Bemme, D. Postsocialism, the Psy-Ences and Mental Health. Transcult. Psychiatry 2016, 53, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skultans, V. From Damaged Nerves to Masked Depression: Inevitability and Hope in Latvian Psychiatric Narratives. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 2421–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skultans, V. The Appropriation of Suffering: Psychiatric Practice in the Post-Soviet Clinic. Theory Cult. Soc. 2007, 24, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formánek, T.; Kagström, A.; Cermakova, P.; Csémy, L.; Mladá, K.; Winkler, P. Prevalence of Mental Disorders and Associated Disability: Results from the Cross-Sectional CZEch Mental Health Study (CZEMS). Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittchen, H.U.; Jacobi, F.; Rehm, J.; Gustavsson, A.; Svensson, M.; Jönsson, B.; Olesen, J.; Allgulander, C.; Alonso, J.; Faravelli, C.; et al. The Size and Burden of Mental Disorders and Other Disorders of the Brain in Europe 2010. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 21, 655–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poh Keong, P.; Chee Sern, L.; Foong, M.; Ibrahim, C. The Relationship between Mental Health and Academic Achievement among University Students—A Literature Review. Second Int. Conf. Glob. Trends Acad. Res. 2015, 2, 755–764. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development Czech Republic Country Note. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/education/Czech%20Republic-EAG2014-Country-Note.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Bobak, M.; Pikhart, H.; Pajak, A.; Kubinova, R.; Malyutina, S.; Sebakova, H.; Topor-Madry, R.; Nikitin, Y.; Marmot, M. Depressive Symptoms in Urban Population Samples in Russia, Poland and the Czech Republic. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2006, 188, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikolajczyk, R.T.; Maxwell, A.E.; El Ansari, W.; Naydenova, V.; Stock, C.; Ilieva, S.; Dudziak, U.; Nagyova, I. Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms in University Students from Germany, Denmark, Poland and Bulgaria. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2008, 43, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pec, O. Mental Health Reforms in the Czech Republic. BJPsych Int. 2019, 16, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagstrom, A.; Alexova, A.; Tuskova, E.; Csajbók, Z.; Schomerus, G.; Formanek, T.; Mladá, K.; Winkler, P.; Cermakova, P. The Treatment Gap for Mental Disorders and Associated Factors in the Czech Republic. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 59, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kale, R. The Treatment Gap. Epilepsia 2002, 43, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doblytė, S. Shame in a Post-Socialist Society: A Qualitative Study of Healthcare Seeking and Utilisation in Common Mental Disorders. Sociol. Health Illn. 2020, 42, 1858–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhry, F.R.; Mani, V.; Ming, L.; Khan, T.M. Beliefs and Perception about Mental Health Issues: A Meta-Synthesis. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, 12, 2807–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, P.; Mladá, K.; Janoušková, M.; Weissová, A.; Tušková, E.; Csémy, L.; Evans-Lacko, S. Attitudes towards the People with Mental Illness: Comparison between Czech Medical Doctors and General Population. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.G.; Ramakrishna, J.; Somma, D. Health-Related Stigma: Rethinking Concepts and Interventions. Psychol. Health Med. 2006, 11, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Link, B.G.; Struening, E.L.; Neese-Todd, S.; Asmussen, S.; Phelan, J.C. Stigma as a Barrier to Recovery: The Consequences of Stigma for the Self-Esteem of People with Mental Illnesses. Psychiatr. Serv. 2001, 52, 1621–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, S.; Serper, M.; Novak, S.; Corrigan, P.; Hobart, M.; Ziedonis, M.; Smelson, D. Self-Stigma, Self-Esteem, and Co-Occurring Disorders. J. Dual Diagn. 2013, 9, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.C.; Corrigan, P.; Larson, J.E.; Sells, M. Self-Stigma in People With Mental Illness. Schizophr. Bull. 2007, 33, 1312–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sickel, A.E.; Seacat, J.D.; Nabors, N.A. Mental Health Stigma: Impact on Mental Health Treatment Attitudes and Physical Health. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Druss, B.G.; Perlick, D.A. The Impact of Mental Illness Stigma on Seeking and Participating in Mental Health Care. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest J. Am. Psychol. Soc. 2014, 15, 37–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.; Golberstein, E.; Gollust, S.E. Help-Seeking and Access to Mental Health Care in a University Student Population. Med. Care 2007, 45, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopinak, J.; Berisha, B.; Mursali, B. An Investigation into the Health of a Representative Sample of Adults in Kosovo. J. Humanit. Assist. 2001, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lannin, D.G.; Vogel, D.L.; Brenner, R.E.; Abraham, W.T.; Heath, P.J. Does Self-Stigma Reduce the Probability of Seeking Mental Health Information? J. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 63, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.J.; Wieling, E.; Simmelink-McCleary, J.; Becher, E. Beyond Stigma: Barriers to Discussing Mental Health in Refugee Populations. J. Loss Trauma 2015, 20, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, L. Depressive Symptoms in a Sample of Social Work Students and Reasons Preventing Students from Using Mental Health Services: An Exploratory Study. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2011, 47, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milin, R.; Kutcher, S.; Lewis, S.P.; Walker, S.; Wei, Y.; Ferrill, N.; Armstrong, M.A. Impact of a Mental Health Curriculum on Knowledge and Stigma Among High School Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 383–391.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoušková, M.; Formánek, T.; Bražinová, A.; Mílek, P.; Alexová, A.; Winkler, P.; Motlová, L.B. Attitudes towards People with Mental Illness and Low Interest in Psychiatry among Medical Students in Central and Eastern Europe. Psychiatr. Q. 2021, 92, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Watson, A.C.; Miller, F.E. Blame, Shame, and Contamination: The Impact of Mental Illness and Drug Dependence Stigma on Family Members. J. Fam. Psychol. 2006, 20, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; Bhundia, R.; Mitra, R.; McEwan, K.; Irons, C.; Sanghera, J. Cultural Differences in Shame-Focused Attitudes towards Mental Health Problems in Asian and Non-Asian Student Women. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2007, 10, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; Procter, S. Compassionate Mind Training for People with High Shame and Self-Criticism: Overview and Pilot Study of a Group Therapy Approach. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2006, 13, 353–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, N.Z.; Sharp, S.E. Shame-Focused Attitudes Toward Mental Health Problems: The Role of Gender and Culture. Rehabil. Couns. Bull. 2014, 57, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Green, P.; Sheffield, D. Mental Health Attitudes, Self-Criticism, Compassion and Role Identity among UK Social Work Students. Br. J. Soc. Work 2019, 49, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. Evolution, Social Roles, and the Differences in Shame and Guilt. Soc. Res. Int. Q. 2003, 70, 1205–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Thibodeau, R.; Jorgensen, R.S. Shame, Guilt, and Depressive Symptoms: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 68–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangney, J.P. Assessing Individual Differences in Proneness to Shame and Guilt: Development of the Self-Conscious Affect and Attribution Inventory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benetti-McQuoid, J.; Bursik, K. Individual Differences in Experiences of and Responses to Guilt and Shame: Examining the Lenses of Gender and Gender Role. Sex Roles 2005, 53, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Stuewig, J.; Mashek, D.J. Moral Emotions and Moral Behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 345–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, M.; Pinto-Gouveia, J. Shame as a Traumatic Memory. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2010, 17, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. The Relationship of Shame, Social Anxiety and Depression: The Role of the Evaluation of Social Rank. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2000, 7, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglar-Nazali, H.P.; Corfield, F.; Cardi, V.; Ambwani, S.; Leppanen, J.; Olabintan, O.; Deriziotis, S.; Hadjimichalis, A.; Scognamiglio, P.; Eshkevari, E.; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of ‘Systems for Social Processes’ in Eating Disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 42, 55–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Green, P.; Sheffield, D. Mental Health Shame of UK Construction Workers: Relationship with Masculinity, Work Motivation, and Self-Compassion. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Las Organ. 2019, 35, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimitsu, K. The Relationship of Guilt and Shame to Mental Health. [The Relationship of Guilt and Shame to Mental Health.]. Jpn. J. Health Psychol. 2001, 14, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kotera, Y.; Conway, E.; Van Gordon, W. Mental Health of UK University Business Students: Relationship with Shame, Motivation and Self-Compassion. J. Educ. Bus. 2019, 94, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Cockerill, V.; Chircop, J.G.E.; Forman, D. Mental Health Shame, Self-compassion and Sleep in UK Nursing Students: Complete Mediation of Self-compassion in Sleep and Mental Health. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 1325–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Green, P.; Sheffield, D. Mental Health of Therapeutic Students: Relationships with Attitudes, Self-Criticism, Self-Compassion, and Caregiver Identity. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, M.E.; Schallert, D.L.; Mohammed, S.S.; Roberts, R.M.; Chen, Y.-J. Self-Kindness When Facing Stress: The Role of Self-Compassion, Goal Regulation, and Support in College Students’ Well-Being. Motiv. Emot. 2009, 33, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D.; Kirkpatrick, K.L.; Rude, S.S. Self-Compassion and Adaptive Psychological Functioning. J. Res. Personal. 2007, 41, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirois, F.M.; Kitner, R.; Hirsch, J.K. Self-Compassion, Affect, and Health-Promoting Behaviors. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Gaerlan, M.J.M. High Self-Control Predicts More Positive Emotions, Better Engagement, and Higher Achievement in School. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2014, 29, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D. Self-Compassion, Self-Esteem, and Well-Being: Self-Compassion, Self-Esteem, and Well-Being. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2011, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D. The Development and Validation of a Scale to Measure Self-Compassion. Self Identity 2003, 2, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacBeth, A.; Gumley, A. Exploring Compassion: A Meta-Analysis of the Association between Self-Compassion and Psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 32, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, Y.W. Contribution of Self-Compassion to Competence and Mental Health in Social Work Students. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2009, 45, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Dosedlova, J.; Andrzejewski, D.; Kaluzeviciute, G.; Sakai, M. From Stress to Psychopathology: Relationship with Self-Reassurance and Self-Criticism in Czech University Students. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, K.D.; Vonk, R. Self-Compassion Versus Global Self-Esteem: Two Different Ways of Relating to Oneself. J. Pers. 2009, 77, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braehler, C.; Gumley, A.; Harper, J.; Wallace, S.; Norrie, J.; Gilbert, P. Exploring Change Processes in Compassion Focused Therapy in Psychosis: Results of a Feasibility Randomized Controlled Trial. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 52, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liss, M.; Erchull, M.J. Not Hating What You See: Self-Compassion May Protect against Negative Mental Health Variables Connected to Self-Objectification in College Women. Body Image 2015, 14, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samaie, G.; Farahani, H.A. Self-Compassion as a Moderator of the Relationship between Rumination, Self-Reflection and Stress. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 30, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollast, R.; Riemer, A.; Sarda, E.; Wiernik, B.; Klein, O. How Self-Compassion Moderates the Relation Between Body Surveillance and Body Shame Among Men and Women. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 2298–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benda, J.; Reichová, A. Psychometrické Charakteristiky České Verze Self-Compassion Scale (SCS-CZ). [Psychometric Characteristics of the Czech Version of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS-CZ).]. Českoslov. Psychol. Časopis Psychol. Teor. Praxi 2016, 60, 120–136. [Google Scholar]

- Montero-Marin, J.; Kuyken, W.; Crane, C.; Gu, J.; Baer, R.; Al-Awamleh, A.A.; Akutsu, S.; Araya-Véliz, C.; Ghorbani, N.; Chen, Z.J.; et al. Self-Compassion and Cultural Values: A Cross-Cultural Study of Self-Compassion Using a Multitrait-Multimethod (MTMM) Analytical Procedure. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstede, G.H. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-8039-7323-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede Insights. Available online: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/czech-republic,germany,the-uk,the-usa/ (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Suveg, C.; Morelen, D.; Brewer, G.A.; Thomassin, K. The Emotion Dysregulation Model of Anxiety: A Preliminary Path Analytic Examination. J. Anxiety Disord. 2010, 24, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing Coping Strategies: A Theoretically Based Approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; 11. [print.]; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984; ISBN 978-0-8261-4191-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sher, K.J.; Grekin, E.R. Alcohol and Affect Regulation. In Handbook of Emotion Regulation; Gross, J.J., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 560–580. [Google Scholar]

- Depue, R.A.; Morrone-Strupinsky, J.V. A Neurobehavioral Model of Affiliative Bonding: Implications for Conceptualizing a Human Trait of Affiliation. Behav. Brain Sci. 2005, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, P. Evolutionary Approaches to Psychopathology: The Role of Natural Defences. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2001, 35, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, P. Compassion: Conceptualisations, Research and Use in Psychotherapy, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-1-58391-982-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiung, D.-Y.; Tsai, C.-L.; Chiang, L.-C.; Ma, W.-F. Screening Nursing Students to Identify Those at High Risk of Poor Mental Health: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, M.; Yasini Ardekani, S.M.; Mirzaei, M.; Dehghani, A. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety and Stress among Adult Population: Results of Yazd Health Study. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2019, 14, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech Ministry of Education. University Students by Groups of Fields and Sex in 2018 [Studenti Vysokých Škol Podle Skupin Oborů a Pohlaví v Roce 2018]; Czech Ministry of Education: Prague, Czech Republic, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The Structure of Negative Emotional States: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, M.M.; Bieling, P.J.; Cox, B.J.; Enns, M.W.; Swinson, R.P. Psychometric Properties of the 42-Item and 21-Item Versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in Clinical Groups and a Community Sample. Psychol. Assess. 1998, 10, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, F.; Pommier, E.; Neff, K.D.; Van Gucht, D. Construction and Factorial Validation of a Short Form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2011, 18, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-60918-230-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hoaglin, D.C.; Iglewicz, B. Fine-Tuning Some Resistant Rules for Outlier Labeling. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1987, 82, 1147–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukey, J.W. The Future of Data Analysis. Ann. Math. Stat. 1962, 33, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. PROCESS: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling [White Paper]. Available online: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Ferreira, C.; Pinto-Gouveia, J.; Duarte, C. Self-Compassion in the Face of Shame and Body Image Dissatisfaction: Implications for Eating Disorders. Eat. Behav. 2013, 14, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Carr, E.R.; Garcia-Williams, A.G.; Siegelman, A.E.; Berke, D.; Niles-Carnes, L.V.; Patterson, B.; Watson-Singleton, N.N.; Kaslow, N.J. Shame and Depressive Symptoms: Self-Compassion and Contingent Self-Worth as Mediators? J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2018, 25, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, M.; Loi, N.M. The Mediating Role of Self-Compassion in Student Psychological Health: Self-Compassion and Psychological Health. Aust. Psychol. 2016, 51, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, B.; Qian, M.; Valentine, J.D. Predicting Depressive Symptoms with a New Measure of Shame: The Experience of Shame Scale. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 41, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, B.; Hunter, E. Shame, Early Abuse, and Course of Depression in a Clinical Sample: A Preliminary Study. Cogn. Emot. 1997, 11, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, D.M.; Williams, M.K.; Quintana, F.; Gaskins, J.L.; Overstreet, N.M.; Pishori, A.; Earnshaw, V.A.; Perez, G.; Chaudoir, S.R. Examining Effects of Anticipated Stigma, Centrality, Salience, Internalization, and Outness on Psychological Distress for People with Concealable Stigmatized Identities. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layte, R.; Whelan, C.T. Who Feels Inferior? A Test of the Status Anxiety Hypothesis of Social Inequalities in Health. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2014, 30, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, S.; Colthurst, K.; Coyle, M.; Elliott, D. Attachment Dimensions as Predictors of Mental Health and Psychosocial Well-Being in the Transition to University. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2013, 28, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-L.; Wang, C.; McDermott, R.C.; Kridel, M.; Rislin, J.L. Self-Stigma, Mental Health Literacy, and Attitudes Toward Seeking Psychological Help. J. Couns. Dev. 2018, 96, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüsch, N.; Müller, M.; Ajdacic-Gross, V.; Rodgers, S.; Corrigan, P.W.; Rössler, W. Shame, Perceived Knowledge and Satisfaction Associated with Mental Health as Predictors of Attitude Patterns towards Help-Seeking. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2014, 23, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotera, Y.; Laethem, M.; Ohshima, R. Cross-Cultural Comparison of Mental Health between Japanese and Dutch Workers: Relationships with Mental Health Shame, Self-Compassion, Work Engagement and Motivation. Cross Cult. Strateg. Manag. 2020. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Sheffield, D. Revisiting the Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form: Stronger Associations with Self-Inadequacy and Resilience. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2020, 2, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redden, E.K.; Bailey, H.N.; Katan, A.; Kondo, D.; Czosniak, R.; Upfold, C.; Newby-Clark, I.R. Evidence for Self-Compassionate Talk: What Do People Actually Say? Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gender (F = 93, M = 20, No Answer = 6) | - | ||||||||

| 2 | Age (19–44 in our sample) | 21.87 | 3.32 | 0.25 ** | - | |||||

| 3 | Mental Health Problems (0–126) | 38.00 | 20.98 | 0.90 | −0.14 | 0.02 | - | |||

| 4 | Negative Mental Health Attitudes (0–24) | 4.50 | 4.63 | 0.86 | 0.20 * | 0.08 | 0.26 ** | - | ||

| 5 | Mental Health Shame (0–81) | 18.34 | 11.55 | 0.90 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.35 ** | 0.56 ** | - | |

| 6 | Self-Compassion (1–5) | 3.08 | 0.60 | 0.81 | 0.12 | 0.002 | −0.54 ** | −0.25 ** | −0.36 ** | - |

| Dependent Variable: Mental Health Problems | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SEB | β | 95% CI | |

| Step 1 | ||||

| Gender | −0.62 | 0.43 | −14 | −1.46, 0.23 |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | −0.10, 0.14 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.001 | |||

| Step 2 | ||||

| Gender | −0.61 | 0.37 | −14 | −1.35, 0.13 |

| Age | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.08 | −0.05, 0.16 |

| Negative Mental Health Attitudes | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.12 | −0.10, 0.42 |

| Mental Health Shame | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.12 | −0.10, 0.38 |

| Self-Compassion | −4.25 | 0.80 | −0.46 *** | −5.84, −2.66 |

| Adj. R2 Δ | 0.29 *** | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kotera, Y.; Andrzejewski, D.; Dosedlova, J.; Taylor, E.; Edwards, A.-M.; Blackmore, C. Mental Health of Czech University Psychology Students: Negative Mental Health Attitudes, Mental Health Shame and Self-Compassion. Healthcare 2022, 10, 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040676

Kotera Y, Andrzejewski D, Dosedlova J, Taylor E, Edwards A-M, Blackmore C. Mental Health of Czech University Psychology Students: Negative Mental Health Attitudes, Mental Health Shame and Self-Compassion. Healthcare. 2022; 10(4):676. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040676

Chicago/Turabian StyleKotera, Yasuhiro, Denise Andrzejewski, Jaroslava Dosedlova, Elaina Taylor, Ann-Marie Edwards, and Chris Blackmore. 2022. "Mental Health of Czech University Psychology Students: Negative Mental Health Attitudes, Mental Health Shame and Self-Compassion" Healthcare 10, no. 4: 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040676

APA StyleKotera, Y., Andrzejewski, D., Dosedlova, J., Taylor, E., Edwards, A.-M., & Blackmore, C. (2022). Mental Health of Czech University Psychology Students: Negative Mental Health Attitudes, Mental Health Shame and Self-Compassion. Healthcare, 10(4), 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040676