The Progress of the New South Wales Aboriginal Oral Health Plan 2014–2020: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

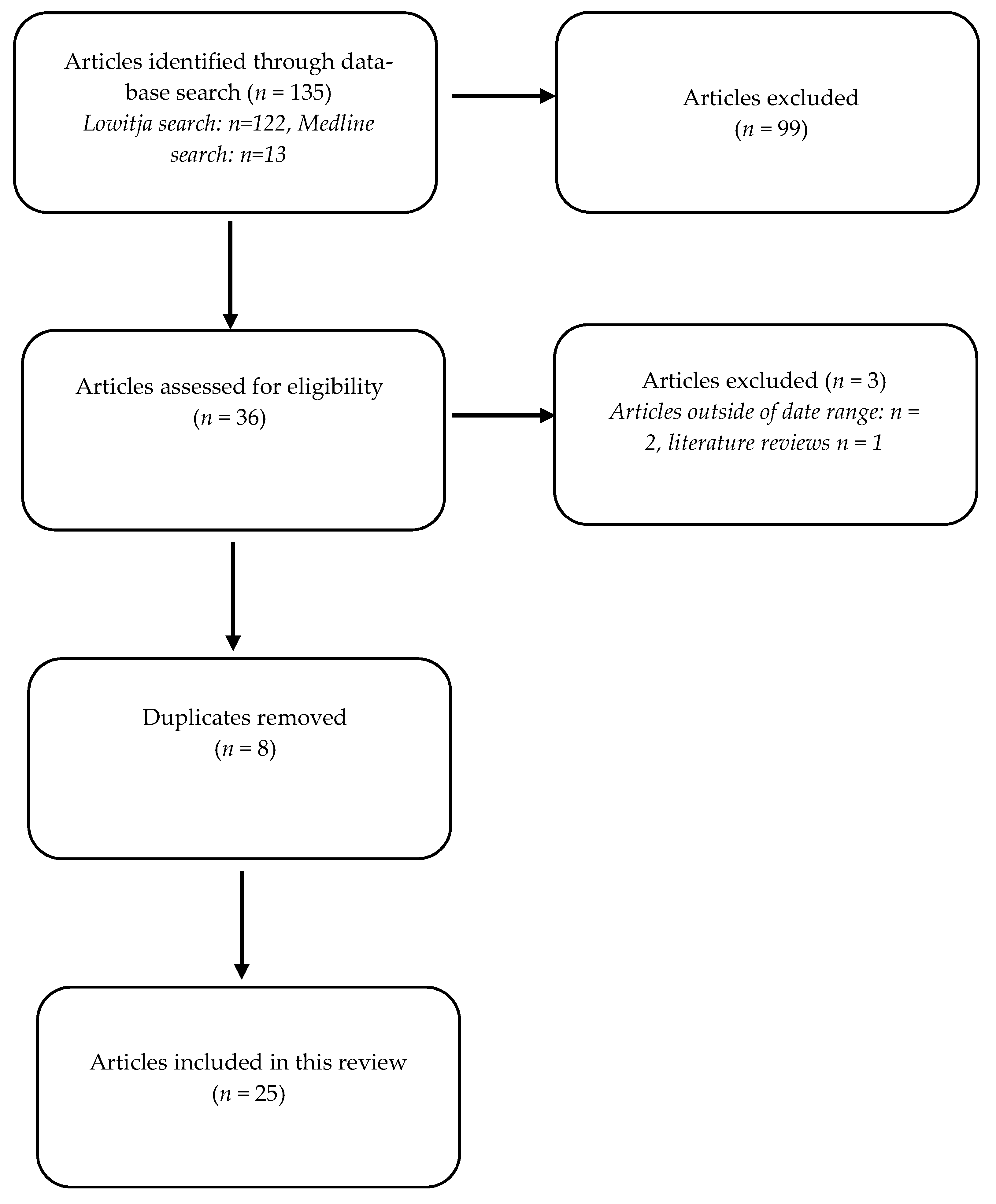

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- Increase access to fluoridated water and fluoride programs to assist in the reduction of dental caries.

- Develop and implement sustainable oral health promotion and prevention programs.

- Improve access to appropriate dental services for Aboriginal people in NSW in culturally safe environments.

- Develop and implement sustainable programs to increase the number of Aboriginal people in the oral health workforce in NSW.

- Strengthen the capacity of the existing and future health and oral health workforce to provide appropriate oral health care in Aboriginal communities.

- Improve oral health for Aboriginal people through supported action-oriented research and improved oral data collections for evaluating both service delivery and oral health outcomes.

2.2. Data Synthesis

2.3. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. Increase Access to Fluoridated Water and Fluoride Programs to Assist in the Reduction of Dental Caries

3.2. Develop and Implement Sustainable Oral Health Promotion and Prevention Programs

3.3. Improve Access to Appropriate Dental Services for Aboriginal People in NSW in Culturally Safe Environments

3.4. Develop and Implement Sustainable Programs to Increase the Number of Aboriginal People in the Oral Health Workforce in NSW

3.5. Strengthen the Capacity of the Existing and Future Health and Oral Health Workforce to Provide Appropriate Oral Health Care in Aboriginal Communities

3.6. Improve Oral Health for Aboriginal People through Supported Action-Oriented Research and Improved Oral Data Collections for Evaluating Both Service Delivery and Oral Health Outcomes

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ha, D.H.; Roberts-Thomson, K.; Arrow, P.; Peres, K.; Do, L.G.; Spencer, A.J. Children’s oral health status in Australia, 2012–2014. In Oral Health of Australian Children: The National Child Oral Health Study 2012–2014; Do, L.G., Spencer, A.J., Eds.; University of Adelaide Press: Adelaide, Australia, 2016; pp. 86–153. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Ministry of Health. NSW Aboriginal Oral Health Plan. 2014–2020; NSW Ministry of Health: Sydney, Australia, 2014. Available online: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/oralhealth/Pages/aboriginal-oral-health-plan.aspx (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gardiner, F.W.; Richardson, A.; Gale, L.; Bishop, L.; Harwood, A.; Lucas, R.M.; Laverty, M. Rural and remote dental care: Patient characteristics and health care provision. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2020, 28, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, C.; Irving, M.; Short, S.; Tennant, M.; Gilroy, J. Strengthening Indigenous cultural competence in dentistry and oral health education: Academic perspectives. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2019, 23, e37–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Forsyth, C.; Short, S.; Gilroy, J.; Tennant, M.; Irving, M. An Indigenous cultural competence model for dentistry education. Br. Dent. J. 2020, 228, 719–725. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitropoulos, Y.; Gwynne, K.; Blinkhorn, A.; Holden, A. A school fluoride varnish program for Aboriginal children in rural New South Wales. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2020, 31, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitropoulos, Y.; Holden, A.; Sohn, W. In-school toothbrushing programs in Aboriginal communities in New South Wales, Australia: A thematic analysis of teachers’ perspectives. Commun. Dent. Health 2019, 36, 106–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, A.; Sousa, M.; Ramjan, L.; Dickson, M.; Goulding, J.; Gwynne, K.; Talbot, F.; Jones, N.; Srinivas, R.; George, A. “Got to build that trust”: The perspectives and experiences of Aboriginal health staff on maternal oral health. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitropoulos, Y.; Holden, A.; Gwynne, K.; Do, L.; Byun, R.; Sohn, W. Outcomes of a co-designed community-led oral health promotion program for Aboriginal children in rural and remote communities in New South Wales, Australia. Commun. Dent. Health 2020, 37, 132–137. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M.A.; Hunt, J.; Walker, D.; Williams, R. The oral health care experiences of NSW Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services. Aust. N. Zldn. J. Stat. 2015, 39, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irving, M.; Gwynne, K.; Angell, B.; Tennant, M.; Blinkhorn, A. Client perspectives on an Aboriginal community led oral health service in rural Australia. Aust. J. Rural Health 2017, 25, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwynne, K.; McCowen, D.; Cripps, S.; Lincoln, M.; Irving, M.; Blinkhorn, A. A comparison of two models of dental care for Aboriginal communities in New South Wales. Aust. Dent. J. 2017, 62, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitropoulos, Y.; Blinkhorn, A.; Irving, M.; Skinner, J.; Naoum, S.; Holden, A.; Masoe, A.; Rambaldini, B.; Christie, V.; Spallek, H.; et al. Enabling Aboriginal dental assistants to apply fluoride varnish for school children in communities with a high Aboriginal population in New South Wales, Australia: A study protocol for a feasibility study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Skinner, J.; Dimitropoulos, Y.; Rambaldini, B.; Calma, T.; Raymond, K.; Ummer-Christian, R.; Orr, N.; Gwynne, K. Costing the Scale-Up of a National Primary School-Based Fluoride Varnish Program for Aboriginal Children Using Dental Assistants in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.; Blinkhorn, F.; Moir, R.; Blinkhorn, A. Results of a two year dental health education program to reduce dental caries in young Aboriginal children in New South Wales, Australia. Commun. Dent. Health 2018, 35, 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitropoulos, Y.; Gunasekera, H.; Blinkhorn, A.; Byun, R.; Binge, N.; Gwynne, K.; Irving, M. A collaboration with local Aboriginal communities in rural New South Wales, Australia to determine the oral health needs of their children and develop a community-owned oral health promotion program. Rural. Remote. Health 2018, 18, 4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dimitropoulos, Y.; Holden, A.; Gwynne, K.; Irving, M.; Binge, N.; Blinkhorn. A. An assessment of strategies to control dental caries in Aboriginal children living in rural and remote communities in New South Wales, Australia. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, J.; Dimitropoulos, Y.; Sohn, W.; Holden, A.; Rambaldini, B.; Spallek, H.; Ummer-Christian, R.; Marshall, S.; Raymond, K.; Calma, T.; et al. Child Fluoride Varnish Programs Implementation: A Consensus Workshop and Actions to Increase Scale-Up in Australia. Healthcare 2021, 8, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, A.; Grace, R.; Elcombe, E.; Villarosa, A.; Mack, H.; Kemp, L.; Ajwani, S.; Wright, D.; Anderson, C.; Bucknall, N.; et al. The oral health behaviours and fluid consumption practices of young urban Aboriginal preschool children in south-western Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Health Promot. J. 2018, 29, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irving, M.; Kumar, N.; Gwynne, K.; Talbot, F.; Blinkhorn, A. Improving oral-health-related quality-of-life for rural Aboriginal communities in Australia utilising a novel mobile denture service. Rural. Remote Health 2019, 19, 5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, A.; Dickson, M.; Ramjan, L.; Sousa, M.S.; Goulding, J.; Chao, J.; George, A. A Qualitative Study Exploring the Experiences and Perspectives of Australian Aboriginal Women on Oral Health during Pregnancy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, N.; Gwynne, K.; Sohn, W.; Skinner, J. Inequalities in the utilisation of the Child Dental Benefits Schedule between Aboriginal* and non-Aboriginal children. Aust. Health Rev. 2021, 45, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irving, M.; Short, S.; Gwynne, K.; Tennant, M.; Blinkhorn, A. “I miss my family, it’s been a while…” A qualitative study of clinicians who live and work in rural/remote Australian Aboriginal communities. Aust. J. Rural Health 2017, 25, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.; Blinkhorn, A.; Moir, R. An assessment of dental caries among young Aboriginal children in New South Wales, Australia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2015, 29, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gwynne, K.; Poppe, K.; McCowen, D.; Dimitropoulos, Y.; Rambaldini, B.; Skinner, J.; Blinkhorn, A. A scope of practice comparison of two models of public oral health services for Aboriginal people living in rural and remote communities. Rural. Remote Health 2021, 21, 5821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwynne, K.; Irving, M.J.; McCowen, D.; Rambaldini, B.; Skinner, J.; Naoum, S.; Blinkhorn, A. Developing a Sustainable Model of Oral Health Care for Disadvantaged Aboriginal People Living in Rural and Remote Communities in NSW, Using Collective Impact Methodology. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2016, 27, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, J.; Dimitropoulos, Y.; Moir, R.; Johnson, G.; McCowen, D.; Rambaldini, B.; Yaacoub, A.; Gwynne, K. A graduate oral health therapist program to support dental service delivery and oral health promotion in Aboriginal communities in New South Wales, Australia. Rural. Remote Health 2021, 21, 5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indigenous Allied Health Australia. IAHA Signs MOU with Indigenous Dentists; Indigenous Allied Health Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2018; Available online: https://iaha.com.au/iaha-signs-mou-with-indigenous-dentists/ (accessed on 17 October 2021).

- Indigenous Allied Health Australia. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Academy Model to Expand under New Funding; Indigenous Allied Health Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2019; Available online: https://iaha.com.au/national-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-health-academy-model-to-expand-under-new-funding/ (accessed on 17 October 2021).

- House Call Doctor. The House Call Doctor Futures in Health Indigenous Scholarship; House Call Doctor: Sydney, Australia, 2017; Available online: https://staging.housecalldoctor.com.au/about/indigenous-scholarship/ (accessed on 17 October 2021).

- Australian Dental Association. Grants for Indigenous Dental Students; Australian Dental Association: Sydney, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://www.ada.org.au/Dental-Professionals/Philanthropy/Grants/Grants-Indigenous-Dental-Students (accessed on 17 October 2021).

- University of Sydney. Sydney Dental Hospital Indigenous Scholarship; University of Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2019; Available online: https://www.sydney.edu.au/scholarships/c/sydney-dental-hospital-indigenous-scholarship.html (accessed on 17 October 2021).

- Charles Sturt University. Albury Wodonga Aboriginal Health Service Scholarship; Charles Sturt University: Sydney, Australia. Available online: https://study.csu.edu.au/get-support/scholarships/find-scholarship/foundation/1st-year/albury-wodonga-aboriginal-health-service-scholarship#tab1 (accessed on 17 October 2021).

- Rogers, J.G. Evidence-Based Oral Health Promotion Resource; Prevention and Population Health Branch, Government of Victoria, Department of Health: Melbourne, Australia, 2011. Available online: https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/publications/policiesandguidelines/Evidence-based-oral-health-promotion-resource-2011 (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Milat, A.; Lee, K.; Conte, K.; Grunseit, A.; Wolfenden, L.; Van Nassau, F.; Orr, N.; Sreeram, P.; Bauman, A. Intervention Scalability Assessment Tool: A decision support tool for health policy makers and implementers. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Health Council. Healthy Mouths Healthy Lives Australia’s National Oral Health Plan 2015–2024; Health Council: Sydney, Australia, 2015. Available online: http://www.coaghealthcouncil.gov.au/Portals/0/Australia%27s%20National%20Oral%20Health%20Plan%202015–2024_uploaded%20170216.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- NSW Ministry of Health. Oral Health 2020: A Strategic Framework for Dental Health in NSW; NSW Ministry of Health: Sydney, Australia, 2013. Available online: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/oralhealth/Pages/oral_health_2020.aspx (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council. AHMRC Oral Health Position Paper: Achieving Oral Health Equity for Aboriginal Communities in NSW; AHMRC: Sydney, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Do, L.G.; Australian Research Centre for Population Oral Health. Guidelines for use of fluorides in Australia: Update 2019. Aust. Dent. J. 2020, 65, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Government. Qualification Details HLT45021—Certificate IV in Dental Assisting (Release 3). Available online: https://training.gov.au/Training/Details/HLT45021 (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Australian Dental Association. Policy Statement 2.2.1—Community Oral Health Promotion: Fluoride Use (Including ADA Guidelines for the Use of Fluoride). 2019. Available online: https://www.ada.org.au/Dental-Professionals/Policies/NationalOral-Health/2–2-1-Fluoride-Use/ADAPolicies_2–2-1_FluorideUse_V1 (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Australian Medical Association. Position Statement—Cultural Safety Australian Medical Association; Australian Medical Association: Barton, Australia, 2021. Available online: https://www.ama.com.au/articles/ama-position-statement-cultural-safety (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Australian Medical Association. AMA Report Card on Indigenous Health No More Decay: Addressing the Oral Health Needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians; Australian Medical Association: Barton, Australia, 2021; Available online: https://www.ama.com.au/article/2019-ama-report-card-indigenous-health-no-more-decay-addressing-oral-health-needs-aboriginal (accessed on 1 November 2021).

| Author, Year | Aim | Methodology | Results | Strategic Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gardiner et al., 2020 [4] | Determine service provision by Royal Flying Doctor Service | Dental services provided by the Royal Flying Doctors Services within rural and remote Australia between April 2017 to September 2018 were analysed | 8992 service episodes, 3407 individual patients, 27,897 services completed | 3 |

| Forsyth et al., 2020 [5] | Examine the integration of Indigenous cultural competence in dental curricula | Four sources of data were analysed:

| Indigenous cultural model developed for dentistry education, Indigenous cultural competence in dentistry education requires governance, adequate resources and education | 5 |

| Forsyth et al., 2019 [6] | Define and explore current Indigenous cultural competence curricula in Dentistry and Medicine programmes at the University of Sydney | Semi-structured interviews were conducted with academics and students. Thematic analysis was conducted to analyse interviews | Six key themes emerged, including transfer of knowledge, barriers, importance, resources, proposed content and strategies. | 5 |

| Dimitropoulos et al., 2020 [7] | Determine if school fluoride varnish programs are feasible | A school fluoride varnish program was developed where fluoride varnish was applied at 3-month intervals for Aboriginal children in rural NSW | 131 children participated in the program Majority (65.4%) received at least three fluoride varnish applications | 1 |

| Dimitropoulos et al., 2019 [8] | Explore experiences of school staff who implemented school toothbrushing programs in Aboriginal communities | Three focus groups conducted thematic analysis used to analyse transcripts | Four themes identified, including program need, routine, responses and sustainability | 2 |

| Kong et al., 2020 [9] | Experiences of Aboriginal health staff towards oral health care during pregnancy | Focus groups conducted with Aboriginal health staff | Four themes identified focusing on the role of Aboriginal health workers promoting maternal oral health. Results can be used to inform a model of oral healthcare for Aboriginal women during pregnancy | 6 |

| Dimitropoulos et al., 2020 [10] | Determine the impact of a community-led oral health promotion program for Aboriginal children in rural NSW that was implemented between 2016 and 2018 | Impact evaluation conducted in 2018, including follow-up dental examination and interviewer-assisted questionnaires compared to baseline data collected in 2014 | Reduction in dental caries, plaque scores and gingivitis. Mean number of teeth affected by dental caries was 4.13 (2018) compared to 5.31 (2014). Increases in positive oral hygiene behaviours | 2 |

| Campbell et al., 2015 [11] | Explore oral health care experiences of ACCHS in NSW | Online surveys and semi structured interviews were conducted within ACCHS in year | Oral health care provided by ACCHS is diverse and reflects the localised approaches they take to deliver primary health care. ACCHSs commonly face barriers in delivering oral health care and are under-acknowledged providers | 6 |

| Irving et al., 2017 [12] | Examine the views of children (and parents) who accessed a new dental service in rural NSW | Survey of the children who accessed this service was conducted between October and December 2014 | High levels of oral pain were reported New dental service was easily accessible All respondents were happy with their treatment | 6 |

| Gwynne et al., 2017 [13] | Compare two models of oral health care for Aboriginal people including those living in rural NSW | Regression analysis was used to compare trends of dental weighted activity units of Model A (Fly-in-fly-out model) and Model B (community-led model) | The community-led model delivered more services for less financial resources | 6 |

| Dimitropoulos et al., 2019 [14] | A study protocol to enable dental assistants to apply fluoride varnish as part of a structured fluoride varnish program | A study protocol for a feasibility study for six Aboriginal dental assistants to undertake training in the application of fluoride varnish and apply fluoride varnish at 3-month intervals as part of a structured school fluoride varnish program | N/A | 1 |

| Skinner et al., 2020 [15] | Provide a costing for the scale-up of a child fluoride varnish program in New South Wales | The number of schools to be targeted as part of a national school fluoride varnish were described, and a costing method developed | Most of the costs of national school fluoride varnish program could be covered by the potential revenue from the Medicare Child Dental Benefits Schedule | 1 |

| Smith et al., 2018 [16] | To assess the effectiveness of a dental health education program ‘Smiles not Tears’ | Aboriginal families with children across eight communities were invited to participate in the ‘Smile not Tears’ program. The program involved Aboriginal Health Workers delivering oral health messages to Aboriginal families with young children | 97% (n = 104) of children in test group were caries-free compared to 65.9% (n = 54) of children in the control group | 2 |

| Dimitropoulos et al., 2018 [17] | Collaborate with Aboriginal communities in rural NSW to understand oral health needs and develop a targeted, community-owned oral health promotion program | Dental health status of Aboriginal children in 2014 was recorded Interviewer-assisted questionnaires conducted with children, parents/guardians and school staff | High level of dental caries and limited toothbrush and toothpaste ownership among children High consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among children Limited oral health knowledge among parents/guardians School staff supportive of oral health promotion | 2 |

| Dimitropoulos et al., 2018 [18] | A study protocol to assess strategies to control dental caries in Aboriginal children | Strategies were to include

| N/A | 2 |

| Skinner et al., 2021 [19] | Identify key actions required to scale-up of school fluoride varnish programs | A workshop was held in Sydney (2018) with dental professionals from different jurisdictions and industry to discuss scale-up of fluoride varnish programs nationally | 44 attendees attended the workshop There was strong support for the scale-up of fluoride varnish programs nationally Workshop recommendations included a standardised protocol, standardised legislation and support for dental assistants to apply fluoride varnish | 1 |

| George et al., 2018 [20] | Examined oral health behaviours and fluid consumption of young Aboriginal children in south-western Sydney | Parents of Aboriginal children aged 18–60 months completed an oral health survey | 20% of parents/guardians were concerned about their child’s oral health 20% of children had seen a dentist 80% were brushing their teeth at least once daily High levels of bottle use were seen up to 30 months and consumption of sugary drinks | 6 |

| Irving et al., 2019 [21] | Evaluate improvements in oral health related quality of life (OHRQoL) of patients who received dentures from a novel mobile denture service | Aboriginal people who received a denture from the new service between July and December 2016 completed a survey at baseline and follow-up. A condensed version of the Oral Health Impact Profile Survey was used | 28 people participated in the survey The effect of oral health on quality of life was improved in all measurement scores, particularly in psychological dimensions | 6 |

| Kong et al., 2021 [22] | Explore attitudes towards oral health among Aboriginal pregnant women and appropriate oral health promotion | Interviews were conducted with pregnant Aboriginal women and analysed thematically | Two themes were identified:

| 5 |

| Orr et al., 2021 [23] | Investigate use of the Child Dental Benefit Schedule (CDBS) among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children | CDBS Data for four financial years (2013–2014 and 2016–2017) was obtained. Logistic regression was used to estimate the odds of Aboriginal children using dental services through the CDBS | The use of the CDBS was lower among Aboriginal children. Aboriginal children were also less likely to access preventive dental services | 6 |

| Irving et al., 2017 [24] | Explore the experiences of dental clinicians who relocated to rural/remote communities to provide dental services in Aboriginal communities in Northern NSW | Semi-structured interviews were conducted with clinicians and reflective diaries kept. These were analysed qualitatively | Three themes were identified:

| 5 |

| Smith et al., 2015 [25] | To assess dental caries among young Aboriginal children | 173 Aboriginal children in metropolitan, rural and remote NSW were examined | Dental caries among children were higher in remote locations when compared to rural and metropolitan areas. Children in remote areas had an average number of 3.5 teeth affected by dental caries compared to 1.5 for children living in rural areas | 6 |

| Gwynne et al., 2021 [26] | Compare the scope of practice for two models of dental service delivery in rural NSW | De-identified dental service records of two models of dental service delivery in rural NSW were clustered according to typical service groupings and analysed for the period 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2015 | Model A (fly-in-fly-out) focused on more complex restorative dental care, whilst model B (community-led) provided a higher level of preventive care | 6 |

| Gwynne et al., 2016 [27] | Describe the steps taken to implement an oral health service for Aboriginal people in Central Northern NSW using the Collective Impact model | Partnerships were formed with the local community, schools and local health service providers to establish a dental service using portable dental equipment and graduate clinicians | The service provided reliable, high-quality care and built local community capacity | 3 |

| Skinner et al., 2021 [28] | Evaluation of a graduate oral health therapist program to support dental service delivery and oral health promotion in Aboriginal communities. | 15 surveys completed by Graduate Oral Health Therapists participating in the Dalang Project between 2016–2018. | Participants reported learning to engage with Aboriginal communities and build cultural competence skills to provide culturally competent oral health services and develop oral health promotion programs. | 2, 3 |

| Scholarship | Organisation | Location | Duration | Eligibility Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The House Call Doctor Futures in Health Indigenous Scholarship [31] | House Call Doctor | National | 1 Year |

|

| Grants for Indigenous Dental Students [32] | Australian Dental Association | National | 1 Year |

|

| Sydney Dental Hospital Indigenous Scholarship [33] | University of Sydney | NSW | 1 Year |

|

| Albury Wodonga Aboriginal Health Service Scholarship [34] | Charles Sturt University | NSW | 1 Year |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maqbool, A.; Selvaraj, C.M.; Lu, Y.; Skinner, J.; Dimitropoulos, Y. The Progress of the New South Wales Aboriginal Oral Health Plan 2014–2020: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040650

Maqbool A, Selvaraj CM, Lu Y, Skinner J, Dimitropoulos Y. The Progress of the New South Wales Aboriginal Oral Health Plan 2014–2020: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2022; 10(4):650. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040650

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaqbool, Ashwaq, Charlotte Marie Selvaraj, Yinan Lu, John Skinner, and Yvonne Dimitropoulos. 2022. "The Progress of the New South Wales Aboriginal Oral Health Plan 2014–2020: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 10, no. 4: 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040650

APA StyleMaqbool, A., Selvaraj, C. M., Lu, Y., Skinner, J., & Dimitropoulos, Y. (2022). The Progress of the New South Wales Aboriginal Oral Health Plan 2014–2020: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 10(4), 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040650