Abstract

Distance learning due to the COVID-19 lockdown, commonly called emergency remote teaching (ERT), substantially changed the methodology of teaching and possibly students’ perceptions of the quality of lectures. Students’ opinions should be collected and analyzed jointly with other data such as academic performance to assess the effect of this pandemic on learning. A 20-question, 4-point Likert scale specific questionnaire was designed and validated twice by a panel of experts. The survey was sent to the 365 industrial engineering undergraduate students enrolled in a chemistry course. Responses (n = 233) and academic data were collected, and four student profiles were identified by using the k-means cluster analysis technique: ‘The Lucky’, ‘The Passive’, ‘The Autonomous Learner’ and ‘The Harmed’. Students experienced the ERT differently according to their profile. Undergraduates who were better autonomous learners excelled in academic performance and were more participative in the survey. In general, students preferred face-to-face classes over distance learning. Undergraduates’ learning has been impaired due to the circumstances. However, contrary to their beliefs, the situation has benefited them with respect to grades when comparing their performance with students from previous years. Discovering what challenges students faced to adapt to the situation is key to giving students tools to grow as autonomous learners and to enable educators to apply tailored teaching techniques to improve the quality of lectures and enhance student satisfaction.

1. Introduction

The Spring semester 2020 was quite different from traditional college semesters due to the COVID-19 lockdown. The switch to emergency remote teaching (ERT) [1] inevitably affected the learning experience of undergraduates around the world. UNESCO estimated that 1 billion students were affected by the school and university closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic [2].

1.1. Quality of Education during ERT

Due to emergency remote teaching, the way in which the seven principles for good practice in undergraduate students [3] are implemented in the degrees’ subjects was affected, as described in the following paragraphs.

Contact between students and lecturers is hindered due to the lack of face-to-face interaction (Principle 1), while socialization among students, key to peer collaboration (Principle 2), is limited to social media and other online tools. In a traditional class environment, students spontaneously talk about academic topics, sharing information and solving doubts among themselves. With the mandatory lockdown and remote classes, students have to voluntarily initiate online conversations with other colleagues, usually those with whom they feel more confident, thereby shrinking their social network.

Regarding the third Principle, active learning has been emphasized since students had to work harder by themselves with ERT. This was due to the fact that face-to-face classes were limited due to health restrictions and the syllabus was usually given in a less guided manner. Some students, especially those in early college years or those deficient in study habits, may have experienced difficulties organizing their assignments and study activities.

With remote classes, giving feedback to students (Principle 4) has been more difficult for teachers since it is more difficult to follow the day-to-day progress of each student, and since some evaluations were cancelled or postponed. Therefore, feedback was often delayed, and this may have affected student expectations regarding their grades in the subjects.

When remote classes were introduced at the beginning of lockdown, students experienced a great shift in the teaching methodology. This probably had a significant effect on the way they organized their study time. The lack of efficient management of their time (Principle 5) when at home all day is one of the problems students may have encountered. In the absence of a pre-established timetable, students failed to dedicate sufficient time to certain tasks. There may also have been an overload of teachers’ assignments, who in turn may have been unable to prepare enough online content on time.

The sixth Principle is to communicate high expectation to students. Due to the global pandemic crisis and the exceptional teaching situation, this is one of the principles that has been highly affected. The general extraordinary situation compromised the expectation excellence from students. Adaptation of the evaluation methods and the flexibility in grading and task timelines, in addition to the diminished student-teacher interaction, together provided the perfect combination for students to lose motivation towards learning and academic excellence.

The last Principle concerns respecting diverse talents and ways of learning. Students have been restricted in the teaching-learning methodologies used by their teachers, who have not had time to adapt the different methodologies they were employing in face-to-face classes during the ERT, and in many cases diversity of teaching-learning methodologies has been lost. As a result, face-to-face classes and other methodologies such as flipped classroom [4,5,6,7,8], project-based learning [9,10] or problem-solving classes were switched to remote lectures by adapting them using the available on-line tools, or simply cancelled.

1.2. Learning Strategies and Student Profiles

Numerous surveys and other studies have been conducted in the past to ascertain the opinions of students and teachers regarding online teaching [11,12,13,14,15]. However, the situation during COVID-19 lockdown was different from regular online courses, as ERT was implemented without time to prepare the classes, and the quality of the teaching-learning process was greatly affected. Additionally, students’ motivation may had been affected as this sudden change of circumstances was imposed, and not a different methodology they could choose to experience.

As it has been reported, there are different learning styles [16], as well as students who adapt better to unexpected changes than others. This greatly influences their attitude towards studying, motivation, as well as the academic performance in the subject [17]. When analyzing student opinions and performance, it is not always recommended to generalize and work with mean values, as information about the different kinds of students is lost, since the variance is rarely uniformly distributed. For this reason, a person-centered approach allows one to detect differences between groups of students with similarities in various dimensions of interest [18,19,20].

As with ERT, the variety of resources and types of classes has been significantly reduced, and students without the ability to effectively benefit from remote lectures have therefore experienced an impaired learning. This has a lot to do with self-regulated, autonomous learning, which has been linked to academic success [21]. Students that are better autonomous learners will benefit from the advantages of online tools, while other scholars may find difficulties adapting to these new resources and methodology. Greater motivation and time management skills, crucial in remote learning environments, have been linked to increased academic performance [22]. Additionally, the students’ digital competencies are significantly correlated with their academic engagement [23], what can cause inequalities in their performance due to a lack of these skills.

To study student differences in depth, profiles are often defined using the clustering technique. In a recent study [24], k-means clustering was applied to classify students according to their physiological health score, in order to study the relation between their mental health and the pandemic. Another paper classified teachers into four profiles according to their use of digital technologies during the COVID-19 lockdown [25]. Previous to the pandemic, a research used the person-centered approach to identify five student profiles in self-regulated learning [26]. The power of the profile definition can be applied further, as it can be a tool to detect students that are having difficulties. Monitoring their learning and enables the application of personalized actions for each individual student according to their profile. A software has been recently patented to monitor student learning in the Moodle platform [27].

The teacher’s role is important in the development of self-regulated, autonomous learning [28]. For this reason, and given the circumstances that took place during lockdown, it is essential to ascertain students’ opinions about ERT in order to understand their points of view and design and implement strategies to cope better with the particularities of the different student profiles in the future. Several case studies all over the world from the Spring 2020 period are being published [29,30,31,32].

Knowing what challenges faced students to adapt to the situation will be beneficial to give students tools to improve and grow as autonomous learners while being able to apply tailored teaching techniques to improve the quality of lectures and student satisfaction.

The first objective of the current research is to gather students’ opinions on the ERT experience. One of the goals of this study is to determine if the ERT semester has changed students’ perspectives on further college courses (for example, by their interest in online courses or other types of blended learning combining traditional face-to-face classes with remote content after the lockdown was lifted). Remote courses provide students with greater flexibility for organizing their time, and by experiencing this first-hand during the ERT, students may have become aware of new learning possibilities. The research is also aimed at identifying possible correlation between students’ opinions and their academic performance, an interesting link that has been studied by several researchers when applied to other situations [33]. Additionally, the research defines student profiles based on the opinion and academic performance combinations. Finally, the students’ expectations grade wise are investigated by asking scholars on their grade forecasts.

2. Materials and Methods

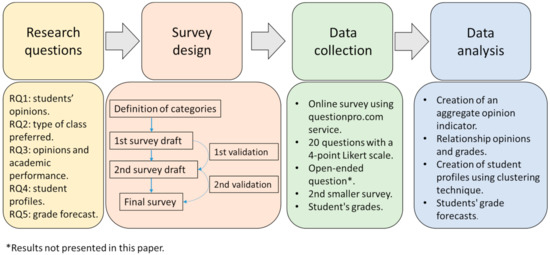

In this section, the ERT methodology used in a case study is presented, as well as the research questions (RQ) and the instruments used to collect students’ opinions and analyze data. A schematic summary of the method is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic methodology used in the research.

2.1. Case Study

The research is focused on studying the opinions of the 365 students belonging to the Bachelor’s Degree in Industrial Technology Engineering at the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya-BarcelonaTech (UPC) Barcelona campus and enrolled in the Spring 19/20 Chemistry course. This course is held during the second semester of the first year of college. Due to the pandemic, the face-to-face classes in this course were replaced by PowerPoint© slides with embedded audio explanations, which are reported as being helpful in establishing instructor presence [34]. Table 1 compares the two methodologies followed during the Spring 2020 Chemistry course, the first five weeks of the course vs. the rest of the semester.

Table 1.

Chemistry course face-to-face and remote methodologies.

In these voice-overs, professors included explanations similar to those they would give in class to address theoretical concepts. Solved exercises were prepared as models for the practical sessions, and documents with extra information based on students’ doubts were made available for all students. All of the material was accessible on the online campus ATENEA, the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya Moodle-based platform. Students were asked to hand in weekly exercises via the online campus, and the solutions were subsequently made available after the due date. Given the extraordinary circumstances, asynchronous activities were preferred over synchronous ones, since not all instructors and students were able at all times to connect to and follow the remote classes.

2.2. Research Questions

The primary goal of this research is to explore the students’ opinions on the teaching-learning methodologies used during the emergency remote teaching. On this basis, five main RQ were formulated:

- (1)

- What are the students’ opinions on a series of categories in the Chemistry subject during the ERT period?

- (2)

- What type of classes do students prefer after lockdown?

- (3)

- Do correlation exist between students’ opinions and their academic performance?

- (4)

- Can students be classified according to their opinion-academic performance combinations during ERT?

- (5)

- What are the students’ grade forecasts depending on whether the Chemistry course is face-to-face or remote?

The methodology and data analysis used to answer each RQ are described in the following sections.

2.2.1. Research Questions 1&2

Research Question 1 (RQ1) tackles a series of categories in relation to ERT. Table 2 shows the categories on which student opinion was gathered.

Table 2.

General categories and the questions that are intended to be answered.

An online survey was defined as the instrument to gather information to answer RQ1 and RQ2. Although there are specific questionnaires available regarding online learning, it was preferred to design a brand-new survey adapted to the subject and context of ERT to answer the research questions. Once the categories were determined, an initial questionnaire draft was prepared to obtain the students’ opinions. This draft was sent for validation to a panel of experts consisting of 23 professors from 14 different Spanish universities. They were asked to complete a table indicating the clarity and relevance of each question according to the predefined categories, as well as to provide comments or changes about the statements.

The validation provided valuable insights that were taken into account when drawing up a further draft of the questionnaire, which was subsequently validated with the same method and by the same experts. The definitive questionnaire was arrived at after this second validation. This process is schematized in Figure 1.

The final version of the questionnaire contained 20 specific questions to be answered by using a 4-point Likert scale to express the degree of agreement (strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree). Questionnaires using the Likert scale are widely used as they are easy to answer and serve to further analyze results [35,36]. A debate on the effect of including a midpoint and its implications on validity and reliability has been running for decades, including empirical researches [37]. Some scholars advocate the use of midpoint, while others advise against it or simply state that midpoints have no impact on Likert-scales’ measures [37,38,39,40]. However, evidence can be found in the literature to the effect that young people associate midpoints more frequently with indecision rather with than neutral opinion, and thus their use is not advisable [41]. For this reason, a 4-point scale was selected so that students did not respond to a central value without opting for either extreme, which would have provided little information.

The questionnaire was distributed in Spanish but an English translation is included in Table 3.

Table 3.

English version of the questionnaire.

Data on student opinion was gathered using the QuestionPro survey online service (www.questionpro.com, accessed on 21 July 2021). This webpage collects the data automatically and a raw data Excel spreadsheet can be downloaded with all the students’ answers.

The questionnaire was sent to the 365 students enrolled in the 19/20 Spring Chemistry course at the end of the semester. It was sent via an email containing a personalized link, and on the last day of the survey a reminder was sent only to those students who had yet to respond. The responses were tracked in order to identify students’ identity through the personalized link in order to associate their answers to the grade obtained in the course. Students were informed about the purpose of the survey and the fact that the data collected would be treated confidentially.

The students of the case study are usually divided into nine class groups, referred to as group 10, group 20, etc., or for convenience G10, G20, G30, G40, G50, G60, G70, G80, and G90. Five different instructors taught the subject during the aforementioned semester. From all the enrolled students, those who voluntarily answered the survey comprise the sample (n = 233), which represents a participation of 64%. The results presented refer only to the opinions of the students who participated, and thus there is an inevitable bias regarding student opinion.

In order to conduct a statistical study of the data obtained through the survey, the qualitative responses were converted into numerical values, assigning a numerical value of 0–3 to each value on the Likert scale, as follows: strongly disagree: 0; disagree: 1; agree: 2; strongly agree: 3. In this way, it was possible to ascertain whether or not students were more or less in agreement with the statement in each question according to its corresponding score.

In general, the higher the score obtained in each of the questions, the better the students value the remote methodology. Statistical calculations were performed with the Stata IC v13 software.

Comments left by students in a final open-ended question were analyzed qualitatively using the constant comparative method of inductive type, which is a type of thematic analysis. This methodology is widely spread in order to analyze student opinions by creating categories composed of similar comments, and many researchers use it as a qualitative method [42,43]. Due to word count limitations, those results are not presented in this paper.

2.2.2. Research Question 3

To answer the RQ3: ‘Do correlation exist between students’ opinions and their academic performance?’, Student t test was used to compare mean values, while a linear regression model was applied to find correlation. Additionally, an analysis of the variance inflation factor was performed, as well as an analysis of assumptions and absence of omitted variables.

2.2.3. Research Question 4

In order to facilitate the study of the types of students based on their behavior during ERT (RQ4: ‘Can students be classified according to their behavior during ERT?’), students’ profiles were created to classify similar opinion-academic performance combinations. To establish these profiles, a cluster analysis was performed as it is the proper statistical technique to accomplish the development of a classification or typology of individuals based on multivariate similarity, [44]. Previous researches in the field of education have applied cluster analysis aiming to examine how the impact of a phenomenon over heterogeneous subgroups [45]. The construction of these profiles took into account:

- The opinions expressed in the 20 questions of the survey;

- The grade obtained in the continuous assessment;

- The final exam grade, and

- The course grade obtained.

With these items, the total number of variables was 23. This analysis assumes a reduction in the number of cases, which may also imply the loss of complexity in the data. In contrast, the usefulness of cluster analysis is that it provides a small number of easy-to-manage profile types for analysis.

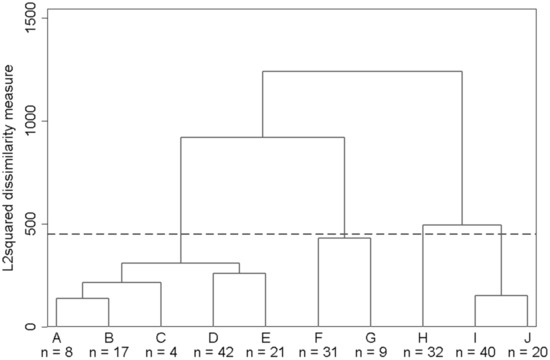

The cluster analysis carried out consists of three stages, the first two of which belong to a hierarchical cluster analysis and the third to a non-hierarchical cluster analysis (k-means). First, a cluster analysis is performed using Ward’s method, which minimizes intra-cluster differences based on Euclidean distances. The cluster analysis starts by considering N students belonging to N clusters of one single student. Then, an iterative process is developed merging in the same cluster those two students most similar at each stage with regard to the 23 variables taken into account. The distance between individuals is measured by the error sum of squares which was defined by Ward [46] as:

where xi is the score of the ith student.

Second, a default range of 3 to 10 clusters is computed. In order to generate a reduced number of clusters of a similar size, it was decided to establish 450 as the threshold for the dissimilarity measure. The students within the same cluster are at a distance ≤ 450. This entails generating four clusters that minimize their internal differences. The dendrogram is found in Figure A1 in Appendix A.

Third and last, a non-hierarchical k-means cluster analysis is performed in which the predefined number of clusters is four. That is, departing from four centroids and starting an iterative process in which each student is allocated in the cluster of the nearest centroid. Then, new four centroids are computed within each cluster. The process converges when no changes of students between cluster takes place in a stage.

2.2.4. Research Question 5

After obtaining the results of the main survey, another smaller survey was designed to obtain more information in relation to Question 13 regarding the students’ grade forecast. The results of this questionnaire allow us to answer RQ5 (‘What are the students’ grade forecasts depending on whether the Chemistry course is face-to-face or remote?’).

This new questionnaire was prepared and sent to a small sample of students on the last day of semester, a few days prior to the final exam, in order to determine their expected grades. The sample were those students in two class groups. The additional two questions enabled the determination of the students’ forecast of the course grade with remote classes as well as their forecast if classes had been face-to-face. These new questions were:

- Question 1: What final grade do you think you will obtain in the Chemistry course?

- Question 2: What final grade do you think you would have obtained in the Chemistry course if it had been entirely face-to-face?

All grades given use the scale 0–10.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents and discusses the answers to the RQ. Graphs have been designed in order to be colorblind-friendly [47].

3.1. Exploratory Analysis and Aggregate Opinion Indicator

Prior to any analysis, an exploration of missing values was carried out to check whether any student had answered the survey at random, and if so it was discarded. No pattern of missing values was detected, while the average number of non-responses was unimportant (0.3%).

An initial exploratory analysis of the questionnaire answers and any possible bias was performed. The analysis of typified residues of responses by groups yielded χ2 = 40.9228; p = 0.000; df = 8 (5.5073 being the threshold for 8 degrees of freedom). There is an over-representation of students from group 10 and an under-representation of students from groups 40 and 60. There are no significant differences in any of the questions between class groups, except for Questions 1, 2 and 14, although with a small effect size according to the rule of thumb provided by Cohen, [48]: 0.1 to 0.3, low effect size; 0.3 to 0.5, medium; 0.5 to 1, large; η2 being between 0–0.2 (η2 = 0.106, 0.103, and 0.107, respectively).

In order to analyze the overall opinion of students, an aggregate opinion indicator was created and validated. The indicator has a range of 0–3 and is calculated by computing the values of the 20 questions. The questions are formulated in a manner that agreeing to them is a sign of a higher acceptation towards ERT. Question 20 is included with reverse coding due to the way the statement is written, compared to the other questions. The aggregate indicator is finally rescaled in order to adjust its scale to the original question scales. A higher indicator implies a more favorable opinion towards remote teaching. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the indicator is 0.853 and the KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) measure of sampling adequacy is 0.847, the threshold being 0.6 and 0.5, respectively. In addition, the Bartlett sphericity test displays variables comprising the indicator are significantly correlated (χ2 = 1434.12; p = 0.000; df = 190). No significant difference in the aggregate opinion indicator is observed among the nine class groups. Some class groups present a higher consistency in their opinions (G10, G30, G50, G90), while others show a wider range of opinions (G60, G70), which may be due to the smaller size of the latter groups. Group 10 is an average group, which represents very well the opinion of the students who answered the survey.

Taking into account the information obtained from the different questions analyzed individually, and grouped as the aggregate opinion indicator, a general consensus is observed among class groups, with differences being an exception rather than the norm. Therefore, opinions discussed in the following sections are no longer classified using class groups.

3.2. RQ1: What Are the Students’ Opinions on a Series of Categories during the ERT Period Regarding the Chemistry Subject?

The students’ opinions about their experience are obtained from questions 1–15 (from now on, abbreviated to Q followed by the number).

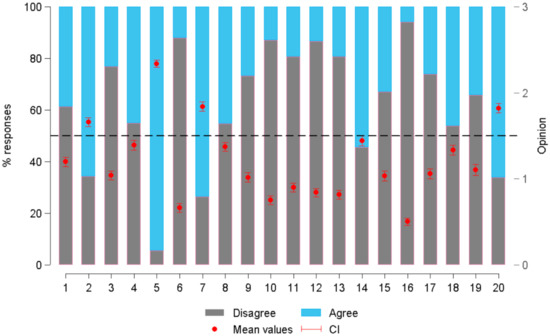

One of the advantages of the lack of central value is the ability to split the responses into two groups, disagree (containing Likert points 0 and 1) and agree (containing Likert points 2 and 3). Figure 2 visually depicts the percentage of responses that agree and disagree with each question indicated by the colored bars (primary axis), as well as the distributions of students’ opinions as mean values (red dot and secondary axis).

Figure 2.

Percentage of responses that agree and disagree with each question and mean opinion values and their confidence intervals.

Since the distribution of opinions range from 0 to 3, opinions overlapping 1.5 (horizontal dashed line) are considered not to display a statistically significant agreement or disagreement on the statements. In this regard, only Q14, ‘As the semester has progressed, my opinion on the remote methodology of this subject has improved’, does not show a significant consensus. However, Q4 and Q8 show a statistically significant consensus, but only to a moderate extent, which can be interpreted as a low level of accord.

Regarding the opinion of the students, the situation of lockdown and remote classes have considerably reduced their perception of socialization, especially with regard to other students. Despite the fact that more than half of the students consider that communication by email with the teacher helps them to solve doubts (Q2), less than a half consider themselves to be equally communicated with the teacher (Q1), and an even lower percentage feel equally connected with their classmates compared with when they attended face-to-face classes (Q3).

Regarding their impressions about learning, students do perceive that being tested without any effect on their grades is beneficial for their learning (Q5). Not all declare that they learn better by trying to solve an exercise by themselves, but prefer to study with a previously solved exercise (Q4). In addition, the students consider that they are not learning more with ERT than with the face-to-face classes from the beginning of the semester (Q6).

Despite the fact that most students believe that the weekly delivery of homework provides them with constant feedback (Q7), approximately half believe that with the ERT they do not know whether they are following the subject properly (Q8). In general, they state that the available material has not been enough to take remote classes (Q9).

The general preference observed is that they do not want to study the theory through voice presentations (Q10). They reaffirm this idea by stating in their responses that they prefer face-to-face classes and consider that these do indeed provide added value (Q12).

Disagreement also exists about the idea of doing the exercises independently instead of attending a face-to-face classes focused on solving problems (Q11), which reinforces the impression that the solved exercises on the online platform were not sufficiently clear for some students.

The results obtained imply that students are more motivated when classes are face-to-face (Q15), although more than a half report that their opinion about the remote emergency methodology has improved throughout the semester (Q14). Furthermore, the majority believe that this situation will not benefit their final grades (Q13).

3.3. RQ2: What Type of Classes Do Students Prefer after Lockdown?

Students’ opinions and preferences towards one methodology over another (in general, not subject-specific) are obtained from Questions 16–20. The distribution of students’ opinions about their preferences for subjects in general can be found in Figure 2. The four questions show a significant agreement on student opinion, as no confidence interval overlaps the 1.5 points dashed line, although Question 18 shows a statistically significant agreement, albeit to a moderate extent, and therefore may be considered as one of the questions with the least agreement.

When asked about a situation without confinement, the students reject the idea of studying in a remote way (Q16), but a greater acceptance is detected in the idea of doing only the theoretical part online and attending face-to-face classes to solve exercises (Q17). Regarding the format, the students prefer classes by video call (Q19) where they can establish eye contact with the teacher (Q20) and solve doubts on the spot. In addition, they seem to appreciate the freedom that non-contact classes give, despite all other considerations (Q18).

Apparently, the lockdown situation experienced during the Spring 2020 semester did not create a generalized preference for remote classes, as face-to-face classes are still their preferred type. On the contrary, probably more than ever before, the majority of students realized the great value of these face-to-face classes due to the lack of them.

3.4. RQ3: Do Correlation Exist between Students’ Opinions and Their Academic Performance?

To investigate whether there was correlation between the aggregate opinion indicator and student’s grades, a Student t test was carried out to compare mean values. The average of the final grades of those students who responded to the survey is significantly higher than that of those who did not, and the effect size is large (t = 5.557, p = 0.000, Cohen’s d = 0.608). In a nutshell, the students who participated in the survey are not evenly distributed among groups, and have better grades than those who did not participate. Therefore, the analysis of the correlation between opinions and grades must take into consideration that the sample includes a bias that tends to take better students into account.

The analysis of the correlation between opinions and final grades was performed using a linear regression model. This model includes the aggregate indicator of opinions on ERT as the dependent variable, and the value of the students’ final grades as the independent variable. In addition, the group to which each student belongs is included as a control variable, with a categorical level of measurement.

Given that the order in which students choose the group to which they are assigned depends on their previous-year grades, it was necessary to rule out possible problems of multicollinearity between grades and groups. Indeed, the analysis of the variance inflation factor indicates that no variable presents a value greater than 2, the acceptability threshold being 10. In addition, the assumptions of normality (z = −0.333; p = 0.63), homoscedasticity (χ2 = 0.03; p = 0.873), and the absence of omitted variables (F = 0.98; p = 0.404) were also confirmed.

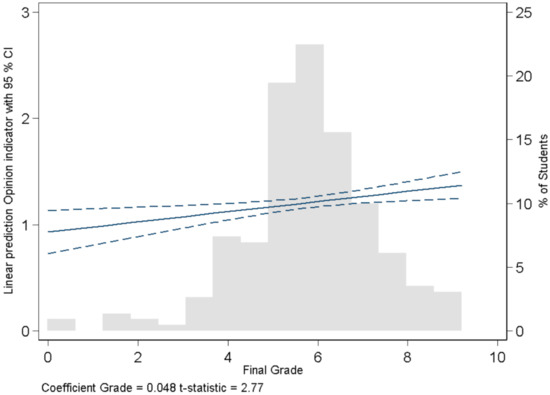

Figure 3 provides a marginal effects plot and a histogram showing that a significantly positive relationship exists between final grades and opinion on ERT (t = 2.77; p = 0.006); that is, controlled for the group to which each student belongs, it is confirmed that those with higher grades tend to have a more favorable opinion of ERT.

Figure 3.

Marginal effects plot and histogram of final grades of the Chemistry course 19/20.

3.5. RQ4: Can Students Be Classified According to Their Behavior during ERT?

As described in the Section 2.2.3, four student profiles were created to study whether or not different types of students exist based on their opinion-academic performance relationship during ERT. The cluster analysis methodology was used to create the clusters.

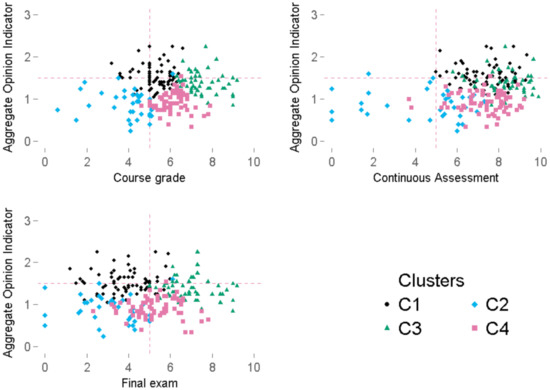

Figure 4 compares the aggregate opinion indicator on ERT and three academic performance measures: the final grades of the course, the continuous assessment, and the final exam results. Each point in the scatterplot represents a student who answered the survey.

Figure 4.

Distribution of student’s profile according to their opinion about ERT and academic performance.

Cluster 3 brings together the students with the best grades, while Cluster 2 contains those with the worst grades. On the other hand, the differences between Clusters 1 and 4 are to be found in the other dimensions of the analysis; that is, in the opinions about remote teaching. Clusters C2 and C4 score lower on the aggregate opinion indicator than the other two. Continuous assessment and final exam grades are significantly different in C1 than in the other three clusters, where a greater coherency in their performance is exhibited. The implications of the data found in Figure 4 are discussed later on in this section.

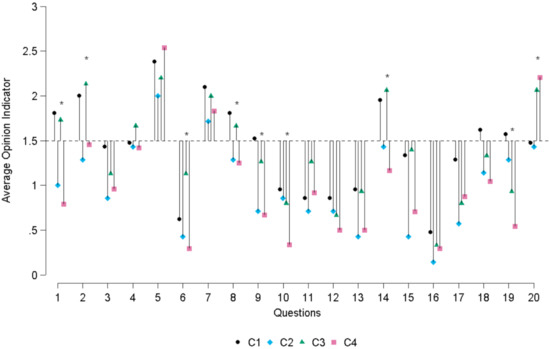

In-depth information can be derived by studying the clusters question by question. Figure 5 shows that two groups of opinions are formed in almost every question, grouping together two clusters containing a similar opinion.

Figure 5.

Aggregate opinion indicator of clusters for each question.

Clusters 1 and 3 score significantly higher than Clusters 2 and 4 in questions 1, 2, 6, 8, 9, 11, 13, 14, 15, and 18, whereas they score higher, but not significantly, in questions 3, 4, 10, 16, and 17. A few questions stand out for displaying different patterns: Cluster 1 scores higher than the others in questions 12 and 19, while Cluster 2 scores lower than the others in question 7. Likewise, it should be highlighted that all clusters display an equal opinion in question 5 (‘Testing myself before the exam without any effect on the grade helps me learn’), the highest ‘agree’ question with also the higher score. Finally, the scores follow inverse score ranking in question 20 due to the way the question is stated, as explained previously.

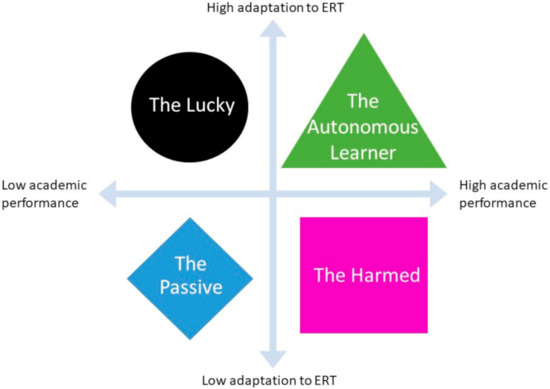

With all the information collected and analyzed, the four student profiles (clusters) can be drawn up as follows:

- Profile 1: ‘The Lucky’. Cluster 1 contains those students most in favor of remote teaching (aggregate indicator 1.53/3). On average, they pass with grades close to five, although 19.12% did pass the subject. These students pass the subject thanks to the continuous assessment, but failed the final exam. They could be considered lucky students, as the lockdown situation has benefited them grade-wise. In a regular semester, they would probably have failed the course. They believe the face-to-face class does not provide much added value, considering what they are capable of doing by themselves with a remote methodology. They also prefer remote classes with slides rather than via videocall, and do not consider visual contact with the teacher as important as the other student profiles.

- Profile 2: ‘The Passive’. Cluster 2 includes students that have a poor opinion about remote teaching (0.85/3) and who in general fail the subject (77.78%) and the final exam (80%), although few of them passed continuous assessment (20%). It is worth emphasizing they did not feel equally communicated with either teacher or peers, and they do not think email communication is sufficient to solve their doubts during remote teaching. In addition, these students prefer to study with a previously solved exercise rather than trying to solve it by themselves. This last point is in accordance with their low grades in continuous assessment, which students could easily overcome simply by handing in exercises they had to solve on their own and guided by a model exercise. A low grade in the continuous assessment is due to the failure to deliver assignments.

- Profile 3: ‘The Autonomous Learner’. Cluster 3 gathers those students who have a relatively favorable opinion towards remote teaching compared to Clusters 2 and 4 (1.36/3), and all of them passed the subject. Their performance in the final exam is much better than the other clusters, but not significantly better than the other profiles in the continuous assessment. These students have acquired the necessary competencies in the subject during the ERT semester, while their opinions score almost as high as Profile 1 students with regard to remote methodology. Therefore, they prove to be good autonomous learners, capable of a good performance under these exceptional circumstances, but who express their preference for face-to-face classes.

- Profile 4: ‘The Harmed’. Cluster 4 consists of students that have a poor opinion about remote teaching (0.87/3) and almost all of them passed the subject (98.61%), although almost a half of them failed the final exam (43.06%). These students exhibit potential as good students, achieving higher grades than Clusters 1 and 2. However, their answers to the survey reveal a deep dislike for the methodology they experienced. These students strongly prefer face-to-face classes, especially for the theoretical part of the subject, and if remote learning is compulsory, they would rather follow online classes instead of prerecorded videos. For this reason, these students are potentially the most harmed by to the change in methodology occasioned by the COVID-19 lockdown.

With these four student profiles identified, the research is closer to a better understanding of the students and how the pandemic impacted the Spring 2020 lockdown semester. Figure 6 displays the four profiles in a quadrant chart.

Figure 6.

Student profiles chart.

Generalizations should not be made, as every undergraduate has different needs and capabilities when facing remote teaching. However, a general discomfort with the situation is evident and completely understandable, and the impact (whether positive or negative) on students depends on their personalities and the individual circumstances they faced during that period.

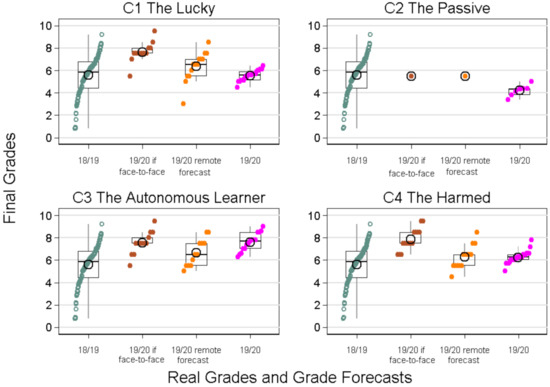

3.6. RQ5: What Are the Students’ Grade Forecast of the Chemistry Course Depending on Whether It Is Face-to-Face or Remote?

Students’ responses (n = 67) to the two-question survey sent to a small sample of students are graphically shown in Figure 7. This figure combines box-plot and scatterplot, showing a descriptive comparison of the distribution of the final grades in the Chemistry course for the previous Spring semester 2018/2019 and for the pandemic 2019/2020 Spring semester. Each point in the graphic is a student grade (scale 0–10); the square box is the interquartile range, with the line being the median and the circle being the average. Each column represents a group of real grades or students’ forecast according to whether the classes were face-to-face or remote. This graphic enables students’ expectations and real grades to be compared. These comparisons are made for each cluster, although it is important to take into account that the 2018/2019 grades are equal for all clusters, as the cluster classification does not include students from the previous chemistry course.

Figure 7.

Students’ grade forecast and actual obtained grades vs. previous course grades.

On the one hand, it is observed that, in general, both grade forecasts are higher than the actual grades obtained by similar students in the previous years. On the other hand, it can be seen that students expect higher grades in the case of face-to-face teaching than in ERT, as seen by the two central columns in each graphic (Figure 7). This indicates that students believe the COVID-19 situation has negatively affected them grade-wise. This second survey found that students not only believe that ERT will not benefit their grade, but that it will actually decrease it.

In relation to the clusters, the final grade obtained by students belonging to ‘The Autonomous Learner’ cluster is closer to their prediction if classes were face-to-face, while the grades obtained by ‘The Lucky’ and ‘The Harmed’ are closer to the predictions for ERT. Only one student from ‘The Passive’ cluster answered the survey. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn from the small sample. Additionally, ‘The Lucky’ and ‘The Harmed’ eventually obtained a grade similar to the average of the previous course without pandemic, while ‘The Passive’ obtained a lower grade and ‘The Autonomous Learner’ a higher one. Therefore, only students in ‘The Autonomous Learner’ cluster exceed their expectation for the course grade. This is an example of the Dunning-Kruger effect [49], where better students underestimate their abilities while less applied students overestimate their academic performance.

When analyzing in general rather than cluster-related, the expected grade for the 19/20 remote course is not significantly related to the actual course grade obtained (r = 0.2396; p = 0.0780; n = 55). There is a positive and significant correlation between the students’ forecast for face-to-face course and the actual course grade 19/20 (r = 0.3110; p = 0.0186; n = 57). To compare different course years, an independent samples Student’s t test was performed, with actual grades or their forecast as a dependent variable and course year as an independent variable. The results show conclusively that there is a statistically significant difference between the face-to-face forecast grade for 19/20 course and the actual face-to-face course held in the previous year 18/19 (t = 7.9099; p = 0.000; n = 153). The forecast is two points higher than the actual grades (scale 0–10).

This implies that the grade obtained by students in the ERT course is similar to the grade they expected if the course had been face-to-face. However, the grade obtained is different to what the students expected of this course being remote. Furthermore, these grade forecasts are well above the real grades obtained by students in the previous year. Although students believe the lockdown situation would lower their grades in comparison to the grades they would obtain in a regular face-to-face course, actually this is not true. The pandemic has benefited their grades when comparing them with previous year grades from equivalent students, since final grades are on the upper side of the 18/19 grade distribution.

It is also interesting to determine the level of participation in this smaller survey on grade forecasting in the different clusters. ‘The Lucky’ and ‘The Harmed’ students participated at levels similar to the average (64.3% and 60.4% of the students in each profile, respectively). On the other hand, ‘The Autonomous Learner’ participated at higher levels (83.3% of students in this cluster answered) and ‘The Passive’ at much lower levels (14.3%), as previously commented, only one student from this category answered this survey. These results are in line with the student profiles, as participative students who are more motivated and involved in the course eventually learn more, and this is reflected in their grades.

Due to the uniqueness of the 19/20 lockdown semester, final grades do not involve the same level of learning as other years. The change in methodology and score weights meant that students were easily able to pass the course even if they failed the final exam. For this reason, the final exam is the only test that actually indicates whether the student has acquired the necessary knowledge. ‘The Autonomous Learner’ profile is the only one that exceeds their grade expectations. It is also the profile in which learning is greatest, as it has a significantly higher final exam score than the rest of the clusters and the average of the previous year (statistical analysis Anova and Scheffe post-hoc tests can be found in Table A1).

Despite the unfavorable opinions regarding the ERT, the students classified as ‘The Autonomous Learner’ were able to adapt to the circumstances, achieving success despite the adversities. It is worth highlighting the importance of an autonomous learning attitude in students, especially in times of crisis such as those experienced due to the pandemic caused by the COVID-19 disease. First-year students often do not have these soft skills, and only a few excel and are able to bounce back in the face of difficulty.

3.7. Limitations of This Work

The data presented in this paper are collected from students who chose to respond to the survey, so the data do not represent all enrolled students. In RQ3 it is found that the sample includes a bias, since students with higher grades are those with a greater participation in the survey.

While it has been pointed out that Questions 16–20 referred to a situation without confinement, students may have responded without taking this into account, since they had never experienced a remote course without confinement. Students may also have expressed their opinions in general, without totally separating their opinion on the specific subject from other courses they were studying at the same time.

To a certain extent, it is normal for students to have negative feelings concerning the remote methodology, since it was applied in complicated socio-political conditions. It is difficult for them to isolate some ideas from others. Moreover, the students had had no previous experience with non-face-to-face methodologies, and they were enrolled in a face-to-face course. Therefore, they were not expecting this methodology change to happen. In addition, first-year students have less experience in college; most of them have still to develop time-management skills and are not yet very good autonomous learners.

Due to the circumstances, this specific study cannot be replicated, as the unprecedented situation students faced was unique. The limitations encountered are logical considering the methodology used and the type of sample. However, taking into account the limitations, the results obtained are useful for the purpose of the study.

3.8. Further Actions and Research

In the first year of the bachelor’s degree, it would be interesting for students to work on the skills they will need throughout their careers and in their professional future, such as advanced computer skills, time management and organization techniques, study habits, autonomous learning, how to search for information on the internet, how to prepare oral presentations, tools to manage stress, etc. These topics may be briefly addressed in all the subjects or scheduled as a specific subject during the first semester at college. These kinds of subjects are often addressed at the end of the studies, sometimes as elective courses, but it is at the beginning when undergraduates need to improve these skills.

On another level, difficulties in accessing electronic equipment and different learning styles put a burden in students, creating inequalities among them when remote learning is implemented. In times of global pandemic or other exceptional situations what may arise in the future, education should not be dismissed. In cases where it is necessary for remote teaching to be implemented, great efforts should be made wherever possible to maintain communication between students and lecturers and the quality of the remote classes, while working towards the improvement of students’ autonomous learning skills.

4. Conclusions

To sum up, the results have made it possible to answer the five research questions (RQ). It was observed that, although a consensus did not always exist on each of the categories raised by the 20-question questionnaire (RQ1), in general the students preferred face-to-face classes (RQ2). Furthermore, students that obtained higher grades in the chemistry course tend to have a better opinion of ERT in comparison to students with a lower academic performance. Additionally, students that participated in the survey had higher grades than those who did not answer the questionnaire (RQ3). By classifying the students into four profiles using the clustering technique it was found that the students experienced the ERT differently according to their profile: ‘The Lucky’, ‘The Passive’, ‘The Autonomous Learner’ and ‘The Harmed’ (RQ4). While some students have apparently benefited from the change in the grading system and online examinations due to the lockdown, others seem to have been harmed due to the lack of interaction with the teacher and peers. On the other hand, it appears that the students exhibiting higher independence and autonomous learning skills have been able to complete the course successfully. Finally, some students failed to complete even the less demanding tasks during lockdown, such as delivering exercises or assignments. This demonstrates that a fraction of the undergraduate population exists that requires a more scheduled course in order to maintain their interest. Finally, students believe the ERT would lower their grade in comparison to the traditional face-to-face course (RQ5), however, contrarily to their beliefs, students overall have benefited from the situation grade-wise.

This work has limitations as the sample includes a bias, since students with higher grades had a higher participation in the survey. Students surveyed were in their first year of college, without previous experience in remote learning. For this reason, is recommended as a further action to develop students’ autonomous learner and other soft skills.

Although ‘new normal’ is being implemented, distance education has gained popularity and will undoubtedly be part of the future of higher and college education to a certain extent. For this reason, a variety of resources should be employed in order to benefit all types of learning. Videocall classes, slides with audio, and remote assignments are recommended to be used jointly, in combination with other methodologies best suited for each specific subject. The results of this study provide key understanding of students’ needs and are another scientific contribution to support the transition into a more tailored remote learning experience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.I.H. and F.S.-C.; investigation, G.I.H.; formal analysis, G.I.H. and D.R.-P.; writing-original draft, G.I.H.; writing-review and editing, G.I.H., F.S.-C., and D.R.-P.; supervision, F.S.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to students’ data protection policies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following panel of experts for taking part in the questionnaire validation process: Agustín Cernuda del Río, Alberto Gómez Mancha, Antoni Pérez Poch, Carlos Catalán Cantero, David López Álvarez, Eva Millán Valldeperas, Faraón Llorens Largo, Francisco J. Gallego-Durán, Imanol Usandizaga Lombana, Inés Jacob Taquet, Joe Miró Julià, José Antonio Cruz Lemus, José Manuel Badia, Juan José Escribano Otero, Julia González Rodríguez, Marcela Genero Bocco, María Asunción Castaño Álvarez, Merche Marqués Andrés, Miguel Riesco Albizu, Miguel Valero García, Óscar Cánovas Reverte, Sergio Barrachina Mir and Xavier Canaleta Llampallas.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Dendrogram for cluster analysis.

Table A1.

Statistical tests regarding mean final exam grades of each Cluster and previous year final exam grades.

Table A1.

Statistical tests regarding mean final exam grades of each Cluster and previous year final exam grades.

| Anova Test | Scheffe Post-Hoc Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | Compar. | Mean Diff. | p |

| 6.06 | 0.000 | 18/19 vs. C1 19/20 | −0.309 | 0.982 |

| 18/19 vs. C2 19/20 | −1.476 | 0.527 | ||

| 18/19 vs. C3 19/20 | 2.357 | 0.002 | ||

| 18/19 vs. C4 19/20 | 0.827 | 0.511 | ||

| C1 19/20 vs. C2 19/20 | −1.167 | 0.822 | ||

| C1 19/20 vs. C3 19/20 | 2.666 | 0.011 | ||

| C1 19/20 vs. C4 19/20 | 1.136 | 0.545 | ||

| C2 19/20 vs. C3 19/20 | 3.832 | 0.005 | ||

| C2 19/20 vs. C4 19/20 | 2.302 | 0.192 | ||

| C3 19/20 vs. C4 19/20 | −1.530 | 0.332 | ||

References

- Hodges, C.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.; Trust, T.; Bond, A. The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educause: 2020. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- UNESCO. Global Education Coalition for COVID-19 Response. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/globalcoalition (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Chickering, A.W.; Gamson, Z.F. Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education. Wingspread J. 1987, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Ritzhaupt, A.D.; Antonenko, P. Effects of the flipped classroom instructional strategy on students’ learning outcomes: A meta-analysis. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2019, 67, 793–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.K.; Hew, K.F. The impact of flipped classrooms on student achievement in engineering education: A meta-analysis of 10 years of research. J. Eng. Educ. 2019, 108, 523–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-González, M.E.; Belmonte, J.L.; Segura-Robles, A.; Cabrera, A.F. Active and emerging methodologies for ubiquitous education: Potentials of flipped learning and gamification. Sustainability 2020, 12, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Izagirre-Olaizola, J.; Morandeira-Arca, J. Business management teaching–learning processes in times of pandemic: Flipped classroom at a distance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Martín, F.-D.; Romero-Rodríguez, J.-M.; Gómez-García, G.; Ramos Navas-Parejo, M. Impact of the Flipped Classroom Method in the Mathematical Area: A Systematic Review. Mathematics 2020, 8, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.C.; Choi, I. Relationship between student designers’ reflective thinking and their design performance in bioengineering project: Exploring reflection patterns between high and low performers. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2019, 67, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Wu, L.; Fischer, C.; Washington, G.; Warschauer, M. Increasing success in college: Examining the impact of a project-based introductory engineering course. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 109, 384–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.; Xu, D.; Rodriguez, F.; Denaro, K.; Warschauer, M. Effects of course modality in summer session: Enrollment patterns and student performance in face-to-face and online classes. Internet High. Educ. 2020, 45, 100710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.D. An investigation of relationships among instructor immediacy and affective and cognitive learning in the online classroom. Internet High. Educ. 2004, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boling, E.C.; Hough, M.; Krinsky, H.; Saleem, H.; Stevens, M. Cutting the distance in distance education: Perspectives on what promotes positive, online learning experiences. Internet High. Educ. 2012, 15, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galikyan, I.; Admiraal, W. Students’ engagement in asynchronous online discussion: The relationship between cognitive presence, learner prominence, and academic performance. Internet High. Educ. 2019, 43, 100692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovai, A.P. Development of an instrument to measure classroom community. Internet High. Educ. 2002, 5, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felder, R.; Silverman, L. learning and teaching styles in engineering education. Eng. Educ. 1988, 78, 674–681. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo-Torres, J.-M.; Hossein-Mohand, H.; Gómez-García, M.; Hossein-Mohand, H.; Hinojo-Lucena, F.-J. Estimating the Academic Performance of Secondary Education Mathematics Students: A Gain Lift Predictive Model. Mathematics 2020, 8, 2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pété, E.; Leprince, C.; Lienhart, N.; Doron, J. Dealing with the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak: Are some athletes’ coping profiles more adaptive than others? Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laursen, B.; Hoff, E. Person-centered and variable-centered approaches to longitudinal data. Merrill. Palmer. Q. 2006, 52, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusurkar, R.A.; Mak-van der Vossen, M.; Kors, J.; Grijpma, J.W.; van der Burgt, S.M.E.; Koster, A.S.; de la Croix, A. ‘One size does not fit all’: The value of person-centred analysis in health professions education research. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P.R. Multiple goals, multiple pathways: The role of goal orientation in learning and achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 92, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, E.C.M.; Jansen, E.P.W.A.; Van De Grift, W.J.C.M. First-year university students’ academic success: The importance of academic adjustment. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 33, 749–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heidari, E.; Mehrvarz, M.; Marzooghi, R.; Stoyanov, S. The role of digital informal learning in the relationship between students’ digital competence and academic engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.K.; Ali, F.B.; Banik, R.; Yasmin, S.; Salma, N. Assessing the mental health condition of home-confined university level students of Bangladesh due to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Public Health 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, J.-I.; Pérez Echeverría, M.-P.; Cabellos, B.; Sánchez, D.L. Teaching and Learning in Times of COVID-19: Uses of Digital Technologies During School Lockdowns. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 656776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, J.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. Profiles in self-regulated learning and their correlates for online and blended learning students. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2018, 66, 1435–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáiz-Manzanares, M.C.; Rodríguez-Díez, J.J.; Díez-Pastor, J.F.; Rodríguez-Arribas, S.; Marticorena-Sánchez, R.; Ji, Y.P. Monitoring of student learning in learning management systems: An application of educational data mining techniques. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, S. The Importance of Autonomous, Self-Regulated Learning in Primary Initial Teacher Training. Front. Educ. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolumole, M. Student life in the age of COVID-19. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2020, 39, 1357–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, D.A.; Yeung, A.; Loedolff, M.; Spagnoli, D. Lessons Learned by Converting a First-Year Physical Chemistry Unit into an Online Course in 2 Weeks. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 2389–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pócsová, J.; Mojžišová, A.; Takáč, M.; Klein, D. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Teaching Mathematics and Students’ Knowledge, Skills, and Grades. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour Almusharraf, N.; Bailey, D.; Daniel Bailey, C. Online engagement during COVID-19: Role of agency on collaborative learning orientation and learning expectations. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lottero-Perdue, P.S.; Lachapelle, C.P. Engineering mindsets and learning outcomes in elementary school. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 109, 640–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Wang, C.; Sadaf, A. Student perception of helpfulness of facilitation strategies that enhance instructor presence, connectedness, engagement and learning in online courses. Internet High. Educ. 2018, 37, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, S.; Kumar, A.; Dutta, R. Effect of integrating IoT courses at the freshman level on learning attitude and behaviour in the classroom. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 26, 2607–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, M.A.; Kääriäinen, M.; Liikanen, E.; Haavisto, E. The comparison of students’ satisfaction between ubiquitous and web-basedlearning environments. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2017, 22, 2565–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyung, S.Y.Y.; Roberts, K.; Swanson, I.; Hankinson, A. Evidence-Based Survey Design: The Use of a Midpoint on the Likert Scale. Perform. Improv. 2017, 56, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adelson, J.L.; McCoach, D.B. Measuring the Mathematical Attitudes of Elementary Students: The Effects of a 4-Point or 5-Point Likert-Type Scale. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2010, 70, 796–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgers, N.; Hox, J.; Sikkel, D. Response effects in surveys on children and adolescents: The effect of number of response options, negative wording, and neutral mid-point. Qual. Quant. 2004, 38, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.L. The Midpoint on a Five-Point Likert-Type Scale. Percept. Mot. Skills 1987, 64, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers, Q.A.W.; Van Hoof, A.; ’T Hart, H.; Verbogt, T.F.M.A.; Vollebergh, W.A.M. Adolescents’ midpoint responses on Likert-type scale items: Neutral or missing values? Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2000, 12, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faber, C.J.; Kajfez, R.L.; McAlister, A.M.; Ehlert, K.M.; Lee, D.M.; Kennedy, M.S.; Benson, L.C. Undergraduate engineering students’ perceptions of research and researchers. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 109, 780–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dringenberg, E.; Purzer, Ş. Experiences of First-Year Engineering Students Working on Ill-Structured Problems in Teams. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 107, 442–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, P. Cluster Analysis. In Handbook of Applied Multivariate Statistics and Mathematical Modeling; Brown, S.D., Tinsley, H.E.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; Volume 366, pp. 297–321. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, L.R. Using cluster analysis in program evaluation. Eval. Rev. 2005, 29, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.H. Hierarchical Grouping to Optimize an Objective Function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischof, D. New graphic schemes for stata: Plotplain and plottig. Stata J. 2017, 17, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 0-8058-0283-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, J.; Dunning, D. Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 1121–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).