Predicting Entrepreneurial Intentions among the Youth in Serbia with a Classification Decision Tree Model with the QUEST Algorithm

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Research Background and Knowledge Gap

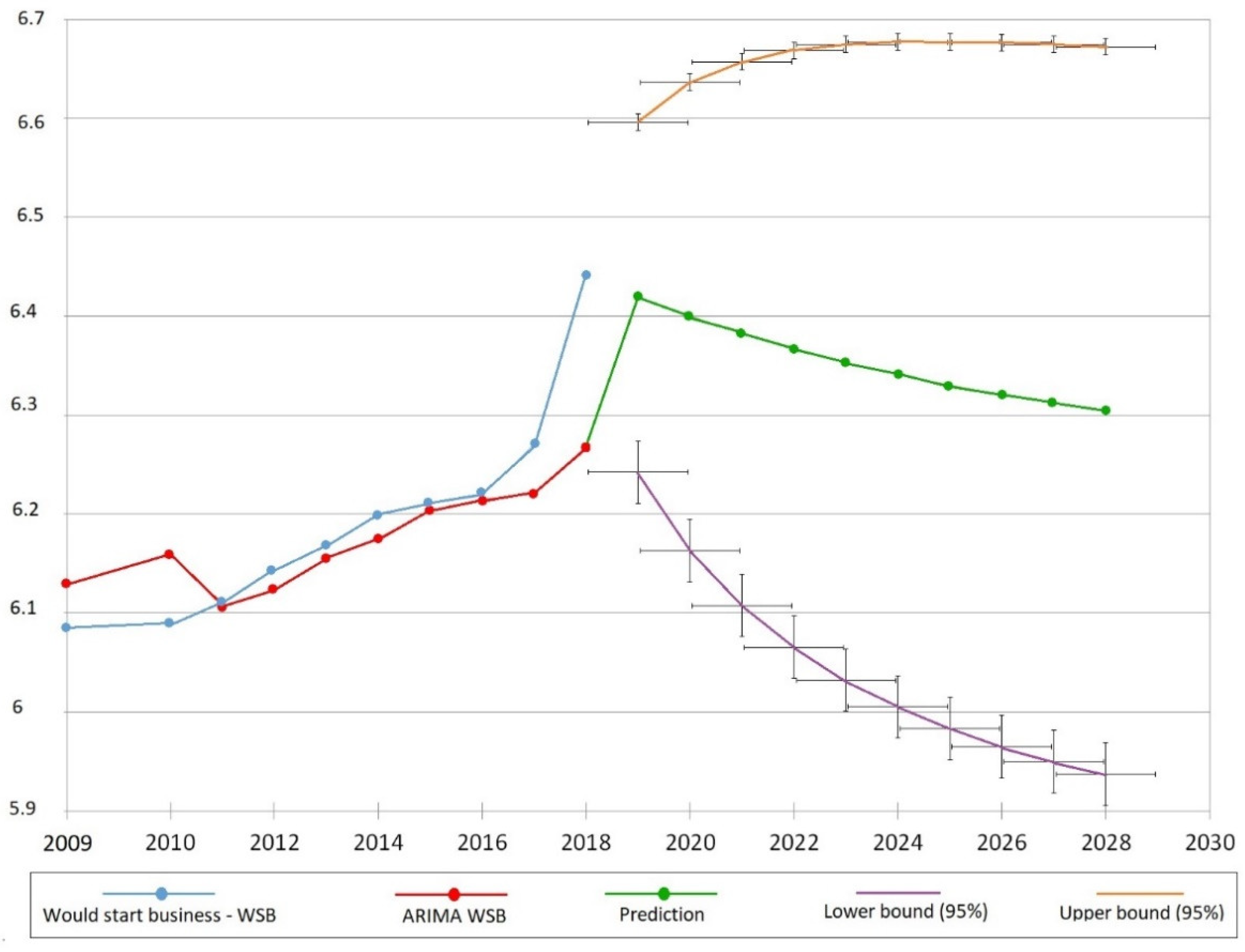

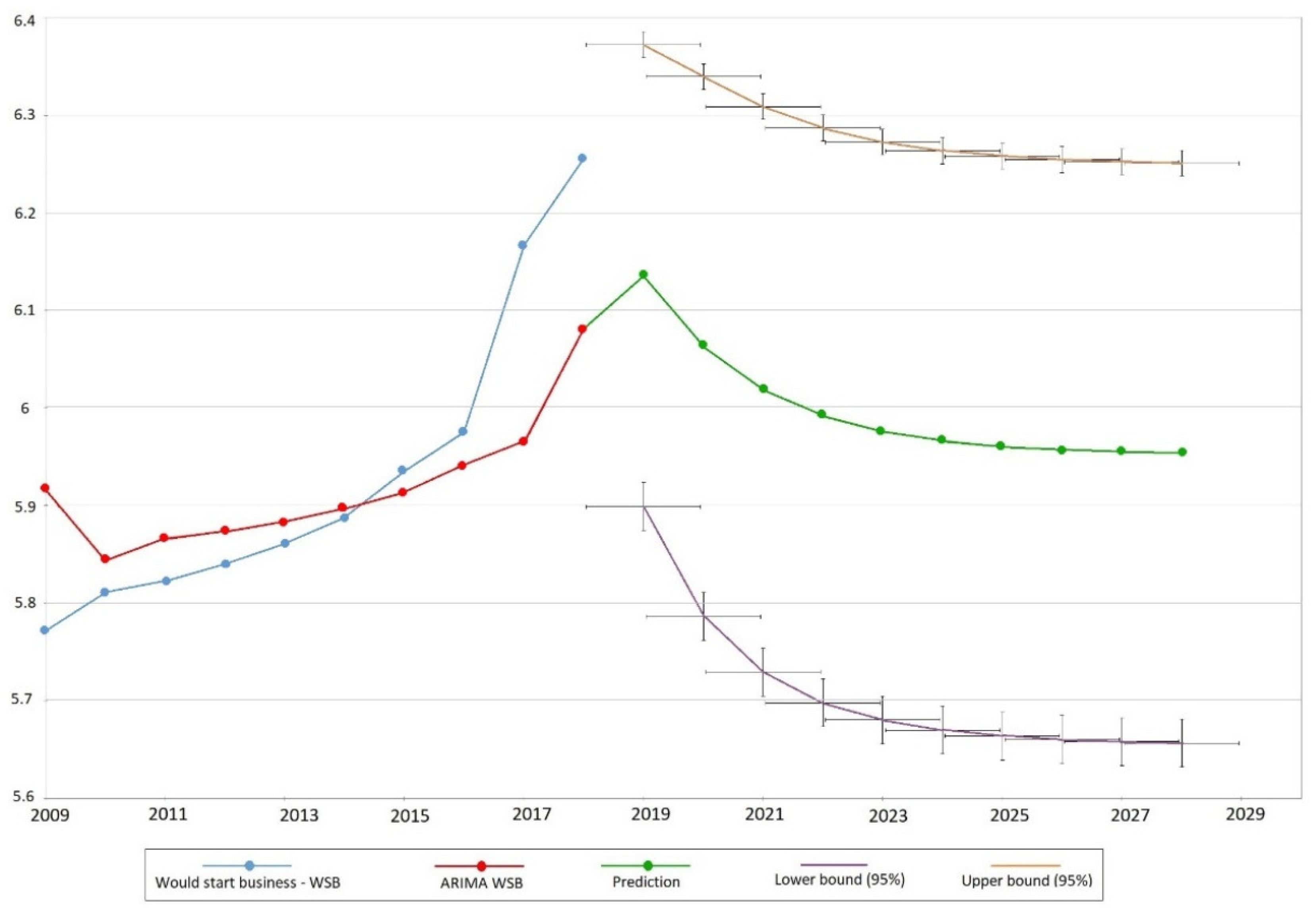

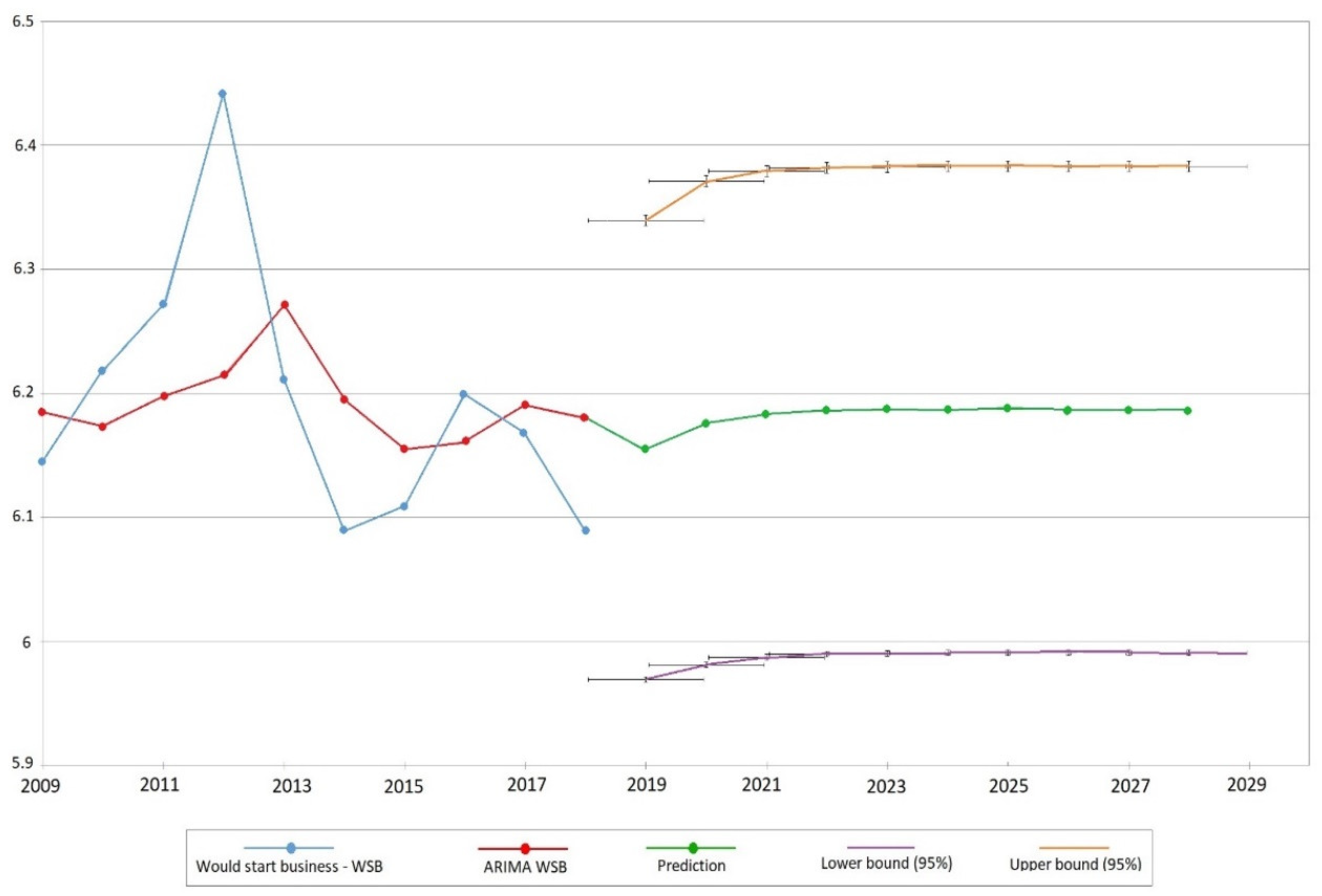

2.1. Entrepreneurship, Economy, and Business Environment in Serbia

2.2. Entrepreneurial Intentions

2.3. Attitudes and Entrepreneurship

2.4. Hypotheses

- H1: Attitudes positively affect student’s intentions to start their own business.

- H2a: Gender positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business.

- H2b: Age positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business.

- H2c: Education positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business.

- H3: Close social environment positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business.

- H4: Awareness of incentive means positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business.

- H5: Environment assessment positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business.

3. Methodology

- Research objective identification (the objective is to attempt to predict entrepreneurial intentions through potential predictors);

- Literature review (writing a theoretical background in the domain of entrepreneurship, intentions, attitudes and other potential influencing factors);

- Data collection (developing a structured survey; distributing the survey, and collecting data from respondents);

- Data analysis and modelling (descriptive statistics, chi-square, Welch’s t-test, z-test, linear regression, binary logistic regression, QUEST classification tree algorithm)

- Model evaluation (determining if it is possible to predict entrepreneurial intentions based on the observed predictors).

- Specify and overall level of significance α ϵ (0, 1).

- Let M be the number of variables, and M1 be the number of continuous and ordinal variables.

- For each continuous or ordered independent variable X, find the smallest p value according to the ANOVA F-test that tests if all the different categories of the dependent variable have the same mean as X, and find the smallest p value according to the Pearson’s chi-squared (χ2) statistic.

- For each categorical independent variable, perform Pearson’s χ2 test of Y and X’s independence, and find the p value according to the χ2 statistic.

- Determine the independent variable with the smallest p value and denote it by X*.

- If this smallest p value is less than α/M, where α ϵ (0, 1) is a user-specified level of significance and M is the total number of independent variables, the independent variable X* is selected as the predictor for splitting the node. If not, go to 4.

- For each continuous independent variable X, compute Levene’ F statistic based on the absolute deviation of X from its class mean to test if the variances of X for different classes of Y are the same, and find the p value for the test.

- Find the independent variable with the smallest p value and denote it by X**.

- If this smallest p value is less than α/(M + M1), where M1 is the number of continuous independent variables, X** is selected as the split independent variable for the node. If not, this node is not split.

- demographic information (gender, age, education)

- close social environment

- attitudes

- awareness of incentive means

- environment assessment

4. Results

- Age has an effect on the readiness to start own business, as older participants are more likely to conduct entrepreneurial activities. Therefore, it can be assumed that age has an influence when it comes to predicting the intention of starting a business.

- If the participant thinks that private businesses are more successful than others, then he is more likely to start his own business.

- If the participant thinks that owning a private business is uncertain and that there is no profit, that he is less prepared to start his own business.

- The participants who answered that the working conditions in a private business is better compared to other types of business are more likely and more ready to start their own business.

- Finally, it is interesting that the data indicates that participants who have a family member who owns a business are less likely to be entrepreneurs.

- The participants who think that start up loans from business banks are affordable are less likely to start their own business.

- The participants who are aware and are familiar with incentive means for starting own business are less likely to start their own business.

- Willingness to use incentive means (Would you be a user of these resources? USERES)

- Attitude on start-up loans (Do you think that start up loans from business banks are affordable for young entrepreneurs? AFFLOAN)

- Parent occupation (Mother’s occupation MOTHOCC) (Father’s occupation FATHOCC)

- -

- Node 1: if (USERES = yes) then class yes = 86.7% and class no = 13.3%

- -

- Node 2: if (USERES = no) then class yes = 70.6% and class no = 29.4%

- -

- Node 3: if (AFFLOAN = no) then class yes = 83.4% and class no = 16.6%

- -

- Node 4: if (AFFLOAN = yes) then class yes = 89.6% and class no = 10.4%

- -

- Node 5: if (MOTHOCC = [retired] OR [agriculture]) then class yes = 56.4% and class no = 43.6%

- -

- Node 6: if (MOTHOCC = [enterprise] OR [institution] OR [private business] OR [unemployed] OR [no data]) then class yes = 73% and class no = 27%

- -

- Node 7: if (MOTHOCC = [institution] OR [no data]) then class yes = 67.2% and class no = 32.8%

- -

- Node 8: if (MOTHOCC = [enterprise] OR [private business] OR [unemployed]) then class yes = 74.9% and class no = 25.1%

- -

- Node 9: if (AFFLOAN = no) then class yes = 62.3% and class no = 37.7%

- -

- Node 10: if (AFFLOAN = yes) then class yes = 75.6% and class no = 24.4%

- -

- Node 11: if (FATHOCC = [enterprise] OR [private business]) then class yes = 77.3% and class no = 22.7%

- -

- Node 12: if (FATHOCC = [unemployed] OR [institution] OR [retired] OR [no data] OR [agriculture]) then class yes = 71.5% and class no = 28.5%

5. Discussion

- H1: Attitudes positively affect student’s intentions to start their own business—not supported.

- H2a: Gender positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—not supported.

- H2b: Age positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—not supported.

- H2c: Education positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—not supported.

- H3: Close social environment positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—not supported.

- H4: Awareness of incentive means positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—not supported.

- H5: Environment assessment positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—not supported.

- H1: Attitudes positively affect student’s intentions to start their own business—failed to be rejected.

- H2a: Gender positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—not supported.

- H2b: Age positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—failed to be rejected.

- H2c: Education positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—failed to be rejected.

- H3: Close social environment positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—failed to be rejected.

- H4: Awareness of incentive means positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—failed to be rejected.

- H5: Environment assessment positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—not supported.

- H1: Attitudes positively affect student’s intentions to start their own business—failed to be rejected.

- H2a: Gender positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—not supported.

- H2b: Age positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—failed to be rejected.

- H2c: Education positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—not supported.

- H3: Close social environment positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—failed to be rejected.

- H4: Awareness of incentive means positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—failed to be rejected.

- H5: Environment assessment positively affects student’s intentions to start their own business—not supported.

- The lack of tracking of respondents to see if their intentions translated into starting their own business (like most studies in this field);

- Not addressing non-English literature and non-Serbian literature sources for the theoretical background;

- Sample structure has limitations regarding data analysis (whether time-series analysis would be appropriate or not, is relative as there are different opinions in the existing body of literature in the domain of statistics);

- Random forest classification was not appropriate with the obtained dataset (probably due to no significant differences between the observed samples);

- Last year students were not analyzed and compared with students from first, second, and third-year students (the sample is not structure appropriately for such analysis);

- Unexplained variance is possible, which may be due to unexplored potential influencing factors), and should be addressed in future research.

- Take notice of the above noted limitations and structure research approach accordingly.

- Include additional external and internal potential predictors of entrepreneurial intentions in the study (economic trends, job market, and national culture could be included in order to obtain a broader view on youth entrepreneurship and economic development factors. Such factors could improve the decision tree modelling process. Internal factors include creativity, intelligence, personality, motivation, social environment, diligence, etc.

- Further, it would be interesting to see how the concept of sustainability affects entrepreneurial intentions in a transition setting, as well how the pandemic affected the entrepreneurial environment.

- The potential influence of dataset size on predicting entrepreneurial intentions could be investigated.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Frist Predictor Group: Sample Size and Structure (Demographic Information) | ||

| Code | Attribute | Description |

| GEN | Gender | Male Female |

| AGE | Age | no specific age range; every age is viewed individually |

| EDU | Education (enrolled in) | high school undergraduate studies

graduate studies—doctorate studies |

| Second Predictor Group: Experience of Family Member Owning a Business (Close Social Environment) | ||

| Code | Attribute | Description |

| FAMBUS | Do you have a member of family who owns a private enterprise? | Yes No |

| FATHOCC MOTHOCC | Father has own business employed—public enterprise employed—private enterprise own business—agriculture in retirement unemployed no answer provided | Mother has own business employed—public enterprise employed—private enterprise own business—agriculture in retirement unemployed no answer provided |

| KNOSKIL | What knowledge and skills do you lack for owning and managing a business? (up to three answers) | Management basics Marketing basics Entrepreneurship and small business basics Accounting basics Computer skills Foreign languages Business communication Other |

| Third Predictor Group: Students’ Attitudes towards Entrepreneurship (Attitudes) | ||

| Code | Attribute | Description |

| MEANBUS | What does private business mean to you? (up to three answers) | Challenge Risk and uncertainty Satisfaction and self-proving |

| WOREN | The working environment in a private enterprise is better compared to public jobs. | I agree I mostly agree I do not know I mostly disagree I disagree |

| MOSUCC | A private enterprise is more successful compared to other types of business. | I agree I mostly agree I do not know I mostly disagree I disagree |

| NOPROF | A private enterprise is not profitable and it is uncertain. | I agree I mostly agree I do not know I mostly disagree I disagree |

| Dependent Variable: Intentions to Start own Business (Entrepreneurial Intentions) | ||

| Code | Attribute | Description |

| STARTBUS (dependent variable) | Would you start your own business? | Yes No |

| Fourth Predictor Group: Students’ Awareness of Existing Incentive Means (Awareness of Incentive Means) | ||

| Code | Attribute | Description |

| RESUSE | With what resources would you start your business? | Private—own Government Bank loans Associated resources |

| AFFLOAN | Do you think that start-up loans from business banks are affordable for young entrepreneurs? | Yes No |

| AWAR | Are aware of the existence of incentive means for starting own business? | Yes No |

| USERES | Would you be a user of these resources? | Yes No |

| Fifth Predictor Group: Serbian Environment in the Context of Entrepreneurship (Environment Assessment) | ||

| CODE | Attribute | Description |

| STIMEN | Is there a stimulating environment in Serbia for starting a business? | Yes No |

| REALIPP | In Serbia, people do not know the real opportunities in the domain of private enterprises. | I agree I mostly agree I do not know I mostly disagree I disagree |

| GOVSTIM | Do you think that the government should have a key role in stimulating the youth to start their own enterprise? | Yes No |

| HOWGOV | How should the government stimulate the young to start their own business? (up to three answers) | Affordable loans Education Better laws and regulation of youth entrepreneurship Development of new business centers and incubators Market regulation Promoting the concept of youth entrepreneurship Other |

Appendix B

| Question | NOTE: Most frequent answers (due to multiple answer by one participant for some questions, the sum of % can exceed 100) |

| Sample size and structure (Demographic information) | |

| Gender | Male (2200 respondents; 38.8%) Female (3470 respondents; 61.2%) |

| Age | Mean 21.9 Variance 7.05 Standard deviation 2.65 Median 21 Mode 21 Percentages: 17 (2 respondents; 0.04%) 18 (164 respondents; 2.89%) 19 (943 respondents; 16.63%) 20 (1011 respondents; 17.83%) 21 (1101 respondents; 19.42%) 22 (579 respondents; 10.21%) 23 (368 respondents; 6.49%) 24 (264 respondents; 4.66%) 25 (344 respondents; 6.07%) 26 (355 respondents; 6.26%) 27 (537 respondents; 9.47%) 28 (1 respondent; 0.02%) 29 (1 respondent; 0.02%) |

| Education (enrolled in) | high school (542 respondents; 9.56%) undergraduate studies (4582 respondents; 80.81%): 1st year (1541 respondents; 27.18%) 2nd year (1241 respondents; 21.89%) 3rd year (954 respondents; 16.82%) 4th year (846 respondents; 14.11%) graduate studies—master (474 respondents; 8.36%) graduate studies—Ph.D. (72 respondents, 1.27%) |

| Experience of family member owning a business (close social environment) | |

| Do you have a member of family who owns a private enterprise? | Yes (2211 respondents; 39.9%) No (3459 respondents; 60.1%) |

| Father has own business (907 respondents; 16%) employed (public enterprise) (680 respondents; 12%) employed (private enterprise) (1928 respondents; 34%) own business—agriculture (340 respondents; 6%) in retirement (851 respondents; 15%) unemployed (567 respondents; 10%) no answer provided (397 respondents; 7%) | Mother has own business (510 respondents; 9%) employed (public enterprise) (1021 respondents; 18%) employed (private enterprise) (1710 respondents; 30%) own business—agriculture (227 respondents; 4%) in retirement (680 respondents; 12%) unemployed (1304 respondents; 23%) no answer provided (227 respondents; 4%) |

| What knowledge and skills do you lack for owning and managing a business? (up to three answers) | Management basics (794 responses; 14%) Marketing basics (675 responses; 11.9%) Entrepreneurship and small business basics (1690 responses; 29.8%) Accounting basics (1395 responses; 24.6%) Computer skills (352 responses; 6.2%) Foreign languages (1661 responses; 29.3%) Business communication (1043 responses; 18.4%) Other (108 responses; 1.9%) |

| Students’ attitudes towards entrepreneurship (attitudes) | |

| What does private business mean to you? (up to three answers) | Challenge (2722 responses; 48%) Risk and uncertainty (2438 responses; 43%) Satisfaction and self-proving (2483 responses; 43%) |

| The working environment in a private enterprise is better compared to public jobs. | I agree (1311 respondents; 23.1%) I mostly agree (1179 respondents; 20.8%) I do not know (904 respondents; 15.9%) I mostly disagree (1329 respondents; 23.4%) I disagree (947 respondents; 16.7%) |

| A private enterprise is more successful compared to other types of business. | I agree (278 respondents; 4.9%) I mostly agree (493 respondents; 8.7%) I do not know (907 respondents; 16%) I mostly disagree (2625 respondents; 46.3%) I disagree (1366 respondents; 24.1%) |

| A private enterprise is not profitable and it is uncertain. | I agree (1463 respondents; 25.8%) I mostly agree (414 respondents; 7.3%) I do not know (1072 respondents; 18.9%) I mostly disagree (811 respondents; 14.3%) I disagree (1905 respondents; 33.6%) |

| Intentions to start own business (entrepreneurial intentions) | |

| Would you start your own business? | Yes (4482 respondents; 79.1%) No (1187 respondents; 20.9%) |

| If not, what are the reasons for not starting your own business? | I do not have the right idea (1327 responses; 23.4%) I do not have enough knowledge (811 responses; 14.3%) Lack of financial resources (2478 responses; 43.7%) Lack of leadership experience (1072 responses; 18.9%) Insecure about own abilities (301 responses; 5.3%) Uncertain political and economic situation (2132 responses; 37.6%) Lack of good associates with who I would start a business (856 responses; 15.1%) I am not interested (822 responses; 14.5%) Other (85 responses; 1.5%) |

| Students’ awareness of existing incentive means (awareness of incentive means) | |

| With what resources would you start your business? | Private—own (3737 respondents; 65.9%) Government (624 respondents; 11%) Bank loans (505 respondents; 8.9%) Associated resources (805 respondents; 14.2%) |

| Are start-up loans from business banks affordable for young entrepreneurs? | Yes (2483 respondents; 43.8%) No (3187 respondents; 56.2%) |

| Are aware of the existence of incentive means for starting own business? | Yes (2444 respondents; 43.1%) No (3226 respondents; 56.9%) |

| Would you be a user of these resources? | Yes (2999 respondents; 52.9%) No (2671 respondents; 47.1%) |

| Serbian environment in the context of entrepreneurship (environment assessment) | |

| Is there a stimulating environment in Serbia for starting a business? | Yes (919 respondents; 16.2%) No (4751 respondents; 83.8%) |

| In Serbia, people do not know the real opportunities in the domain of private enterprises. | I agree (221 respondents; 3.9%) I mostly agree (2843 respondents; 5%) I do not know (658 respondents; 11.6%) I mostly disagree (1899 respondents; 33.5%) I disagree (2608 respondents; 46%) |

| What are the biggest limitations for starting own business? | Lack of financial resources (4394 responses; 77.5%) Limited market (1497 responses; 26.4%) Unstable political and economic situation (4326 responses; 76.3%) Disloyal competition (1089 responses; 19.2%) High tax rates (3204 responses; 56.5%) Other (34 responses; 0.6%) |

| Do you think that the government should have a key role in stimulating the youth to start their own enterprise? | Yes (5058 respondents; 89.2%) No (612 respondents; 10.8%) |

| How should the government stimulate the young to start their own business? (up to three answers) | Affordable loans (4043 responses; 71.3%) Education (3544 responses; 62.5%) Better laws and regulation of youth entrepreneurship (2308 responses; 40.7%) Development of new business centers and incubators (1191 responses; 21.0%) Market regulation (2121 responses; 37.4%) Promoting the concept of youth entrepreneurship (1752 responses; 30.9%) Other (28 responses; 0.5%) |

References

- Bruton, G.D.; Ahlstrom, D.; Obloj, K. Entrepreneurship in emerging economies: Where are we today and where should the research go in the future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2008, 32, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, A.E.; Settles, A.; Shen, T. Does family support matter? The influence of support factors on entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions of college students. Acad. Entrep. J. 2017, 23, 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Fadeyi, O.; Oke, A.O.; Ajagbe, M.A.; Isiavwe, D.T.; Adegbuyi, A. Impact of youth entrepreneurship in nation building. Int. J. Acad. Res. Pub. Pol. Govern. 2015, 2, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louga, S.N.; Mouloungni, A.N.; Sahut, J.M. Entrepreneurial intention and career choices: The role of volition. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornskov, C.; Foss, N.J. Institutions, Entrepreneurship, and Economic Growth: What Do We Know and What Do We Still Need to Know? Acad. Man. Persp. 2016, 30, 292–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martynova, S.E.; Dmitriev, Y.G.; Gajfullina, M.M.; Totskaya, Y.A. “Service” Municipal Administration as Part of the Development of Youth Entrepreneurship in Russia. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 133, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, Z.K.; Herman, E. Innovative Entrepreneurship for Economic Development in EU. Proc. Econ. Finan. 2012, 3, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakator, M.; Đorđević, D.; Ćoćkalo, D. Developing a model for improving business and competitiveness of domestic enterprises. J. Eng. Manag. Comp. 2019, 9, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćoćkalo, D.; Đorđević, D.; Nikolić, M.; Stanisavljev, S.; Stojanović, E.T. Analysis of possibilities for improving entrepreneurial behaviour of young people: Research results in Central Banat district. J. Eng. Manag. Comp. 2017, 7, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kiuma, A.K.; Araar, A.; Kaghoma, C.K. Internal migration and youth entrepreneurship in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2020, 23, 790–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Soon, N.; Ahmad, A.R.; Ibrahim, N.N. Theory of planned behavior: Undergraduates’ entrepreneurial motivation and entrepreneurship career intention at a public university. J. Entrep. Res. Pract. 2016, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiko, Y.C.; Stefenon, S.F.; Ramos, N.K.; Silva, S.V.; Forbici, F.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Silva, F.C.; Cassol, A.; Marietto, M.L.; Farias, S.K.; et al. Young People’s Perceptions about the Difficulties of Entrepreneurship and Developing Rural Properties in Family Agriculture. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, M.A.; Herman, E. The Impact of the Family Background on Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions: An Empirical Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, S.; Nadeem, M.A.; Khan, M.K.; Anwar, M.A.; Iqbal, M.B.; Asmi, F. Opportunity Recognition Behavior and Readiness of Youth for Social Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Res. J. 2019, 20180201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliakis, S.; Kotsopoulos, D.; Karagiannaki, A.; Pramatari, K. Survival and Growth in Innovative Technology Entrepreneurship: A Mixed-Methods Investigation. Admin. Sci. 2020, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meoli, A.; Fini, R.; Sobrero, M.; Wiklund, J. How entrepreneurial intentions influence entrepreneurial career choices: The moderating influence of social context. J. Bus. Vent. 2019, 105982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausken, K.; Moxnes, J.F. Innovation, Development and National Indices. Soc. Ind. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Siegel, D.; Kenney, M. On open innovation, platforms, and entrepreneurship. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, P. The Orderly Entrepreneur: Youth, Education and Governance in Rwanda by Catherine A. Honeyman Stanford; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2016; 320p, ISBN 0804797978. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, P.Y.; Clercq, D.D. Explaining the entrepreneurial intentions of employees: The roles of societal norms, work-related creativity and personal resources. Int. Small Bus. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, K.; Williams, C. Maximising the Impact of Youth Entrepreneurship Support in Different Contexts; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterbeek, H.; van Praag, M.; Ijsselstein, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship skills and motivation. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2010, 54, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogatyreva, K.; Edelman, L.F.; Manolova, T.S.; Osiyevskyy, O.; Shirokova, G. When do entrepreneurial intentions lead to actions? The role of national culture. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, A.; Chapman, D.W.; DeJaeghere, J.; Pekol, A.R.; Weiss, T. Youth Entrepreneurship Education and Training for Poverty Alleviation: A Review of International Literature and Local Experiences. Int. Persp. Edu. Soc. 2014, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.E.; Cliff, J.E. The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: Toward a family embeddedness perspective. J. Bus. Vent. 2003, 18, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Anwar, I.; Saleem, I.; Islam, K.B.; Hussain, S.A. Individual entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of entrepreneurial motivations. Ind. Higher Edu. 2021, 09504222211007051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Shabir, S.; Shaikh, A. Exploring antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions among females in an emerging economy. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggadwita, G.; Ramadani, V.; Permatasari, A.; Alamanda, D.T. Key determinants of women’s entrepreneurial intentions in encouraging social empowerment. Serv. Bus. 2021, 15, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurel, E.; Madanoglu, M.; Altinay, L. Gender, risk-taking and entrepreneurial intentions: Assessing the impact of higher education longitudinally. Educ. Train. 2021, 5, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carree, M.A.; Thurik, A.R. The impact of entrepreneurship on Economic growth. In Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosique-Blasco, M.; Madrid-Guijarro, A.; García-Pérez-de-Lema, D. The effects of personal abilities and self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intentions. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 1025–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollingtoft, A.; Ulhoi, J.P. The networked business incubator—Leveraging entrepreneurial agency? J. Bus. Vent. 2005, 20, 265–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M.; Caiazza, R.; Lehmann, E.E. Knowledge management and entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Man. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anjum, T.; Ramzani, S.R.; Nazar, N. Antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions: A study of business students from universities of Pakistan. Int. J. Bus. Psych. 2019, 1, 72–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ćoćkalo, D.; Đorđević, D.; Nikolić, M.; Stanisavljev, S.; Stojanović, E.T. An exploratory study of relationship between entrepreneurship and economic development—Central Banat Region. Research Results. In Proceedings of the VIII International Symposium Engineering Management and Competitiveness (EMC 2018), Zrenjanin, Serbia, 22–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group. Doing Business. 2020. Available online: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2020 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- World Bank Group. Doing Business. 2019. Available online: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2019 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- World Bank Group. Doing Business. 2018. Available online: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2018 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- World Bank Group. Doing Business. 2017. Available online: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2017 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- World Bank Group. Doing Business. 2016. Available online: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2016 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- World Bank Group. Doing Business. 2015. Available online: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2015 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- World Bank Group. Doing Business. 2014. Available online: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2014 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- World Bank Group. Doing Business. 2013. Available online: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2013 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- World Bank Group. Doing Business. 2012. Available online: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2012 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- World Bank Group. Doing Business. 2011. Available online: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2011 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- World Bank Group. Doing Business. 2010. Available online: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2010 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- World Bank Group. Doing Business. 2009. Available online: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2009 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Escolar-Llamazares, M.C.; Luis-Rico, I.; de la Torre-Cruz, T.; Herrero, Á.; Jiménez, A.; Palmero-Cámara, C.; Jiménez-Eguizábal, A. The Socio-educational, Psychological and Family-Related Antecedents of Entrepreneurial Intentions among Spanish Youth. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stamboulis, Y.; Barlas, A. Entrepreneurship education impact on student attitudes. Int. J. Man. Edu. 2014, 12, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuberes, D.; Priyanka, S.; Teignier, M. The determinants of entrepreneurship gender gaps: A cross-country analysis. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2018, 23, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baluku, M.M.; Leonsio, M.; Bantu, E.; Otto, K. The impact of autonomy on the relationship between mentoring and entrepreneurial intentions among youth in Germany, Kenya, and Uganda. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 25, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simatupang, R.A.; Bajari, M. Entrepreneurial Intentions: Theory of Planned Behavior Perspectives. KnE Soc. Sci. 2021, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entrialgo, M.; Iglesias, E. Entrepreneurial intentions among university students: The moderating role of creativity. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2020, 17, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, S.; Šarlija, N.; Zekić Sušac, M. Shaping the entrepreneurial mindset: Entrepreneurial intentions of business students in Croatia. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.P.; Lopes, J.M.; Carvalho, C.; Vieira, B.M.M.; Lopes, J. Education as a key to provide the growth of entrepreneurial intentions. Educ. Train. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikou, S.; Brännback, M.; Carsrud, A.L.; Brush, C.G. Entrepreneurial intentions and gender: Pathways to start-up. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2019, 3, 348–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowiński, W.; Haddoud, M.Y.; Lančarič, D.; Egerová, D.; Czeglédi, C. The impact of entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and gender on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the Visegrad countries. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajković, J.; Poštin, J.; Konjikušić, M.; Rusić, A.J.; Stojković, H.S.; Nikolić, M. The enterprise potential, individual entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial intentions of students in Serbia. Eur. J. Appl. Econ. 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkar, Y.; Durst, S.; Gerstlberger, W. The Impact of Institutional Dimensions on Entrepreneurial Intentions of Students—International Evidence. J. Risk Fin. Man. 2021, 14, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furdui, A.; Lupu-Dima, L.; Edelhauser, E. Implications of Entrepreneurial Intentions of Romanian Secondary Education Students, over the Romanian Business Market Development. Processes 2021, 9, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodă, A.I.; Florea, N. Impact of personality traits and entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions of business and engineering students. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hueso, J.A.; Jaén, I.; Liñán, F.; Basuki, W. The influence of collectivistic personal values on the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2020, 026624262090300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zampetakis, L.A.; Beldekos, P.; Moustakis, V.S. ‘‘Day-to-day” entrepreneurship within organisations: The role of trait Emotional Intelligence and Perceived Organisational Support. Eur. Man. J. 2009, 27, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-López, Á.; Souto, J.E. Empowering entrepreneurial capacity: Training, innovation and business ethics. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mylonas, N.; Kyrgidou, L.; Petridou, E. Examining the impact of creativity on entrepreneurship intentions: The case of potential female entrepreneurs. World Rev. Entrep. Man. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 2, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 4, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S. The role of entrepreneurial passion in the formation of students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Appl. Econ. 2020, 52, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dioneo-Adetayo, E.A. Factors Influencing Attitude of Youth Towards Entrepreneurship. Int. J. Adoles. Youth 2006, 13, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, S.G.; Block, J.H. Outcomes of entrepreneurship education: An institutional perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 31, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Popescu, C.C.; Bostan, I.; Robu, I.B.; Maxim, A. An analysis of the determinants of entrepreneurial intentions among students: A romanian case study. Sustainability 2016, 8, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y.W. Development and Cross-Cultural Application of a Specific Instrument to Measure Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrep. Theory Prac. 2009, 3, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.S.; Loh, W.Y.; Shih, Y.S. An Empirical Comparison of Decision Trees and Other Classification Methods (Technical Report 979); Department of Statistics, University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, N.F. Entrepreneurial intentions are dead: Long live entrepreneurial intentions. In Revisiting the Entrepreneurial Mind; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-González, J.A.; Kobylinska, U.; García-Rodríguez, F.J.; Nazarko, L. Antecedents of Entrepreneurial Intention among Young People: Model and Regional Evidence. Sustainability 2019, 24, 6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shirokova, G.; Tsukanova, T.; Morris, M.H. The Moderating Role of National Culture in the Relationship Between University Entrepreneurship Offerings and Student Start-Up Activity: An Embeddedness Perspective. J. Small Bus. Man. 2017, 56, 103–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strauß, P.; Greven, A.; Brettel, M. Determining the influence of national culture: Insights into entrepreneurs’ collective identity and effectuation. Int. Entrep. Man. J. 2020, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajković, J.; Nikolić, M.; Ćoćkalo, D.; Stojanović, E.T.; Kovačić, S. National culture and the entrepreneurial intentions of students in Serbia. JEEMS J. E. Eur. Mana. Stud. 2020, 25, 105–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, H.; Abdullateef, O. Entrepreneurial intentions of business students in Malaysia: The role of self-confidence, educational and relation support. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 53 Díaz-Casero, J.C.; Fernández-Portillo, A.; Sánchez-Escobedo, M.C.; Hernández, M. The Influence of University Context ON Entrepreneurial Intentions. In Entrepreneurial Universities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunduz, M.; Lutfi, H.M.A. Go/No-Go Decision Model for Owners Using Exhaustive CHAID and QUEST Decision Tree Algorithms. Sustainability 2021, 13, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Logan, H.L.; Glueck, D.H.; Muller, K.E. Selecting a sample size for studies with repeated measures. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Crowder, M.J.; Hand, D.J. Analysis of Repeated Measures; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Loh, W.; Shih, Y. Split selection methods for classification trees. Stat. Sin. 1997, 7, 815–840. [Google Scholar]

- Qabbaah, H.; Sammour, G.; Vanhoof, K.; Voronin, A.; Ziatdinov, Y.; Aslanyan, L.; Honchar, A. Decision tree analysis to improve e-mail marketing campaigns. Int. J. Inf. Theor. Appl. 2019, 26, 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, P. Springer Handbook of Engineering Statistics; Rutgers the State University of New Jersey: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zukhronah, E.; Susanti, Y.; Pratiwi, H.; Respatiwulan, H. Decision tree technique for classifying cassava production. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 1, 060013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamy, S.; Dheeba, J. Review of QUEST, GUIDE, CRUISE, C4.5 and RPART Classification Algorithms. Int. J. Adv. Tech. Eng. Sci. 2016, 6, 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, A. Decision Trees for Evaluation of Mathematical Competencies in the Higher Education: A Case Study. Mathematics 2020, 8, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gocheva-Ilieva, S.; Kulina, H.; Ivanov, A. Assessment of Students’ Achievements and Competencies in Mathematics Using CART and CART Ensembles and Bagging with Combined Model Improvement by MARS. Mathematics 2021, 9, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, W.Y. User Manual for GUIDE v36.2. 2021. Available online: http://pages.stat.wisc.edu/~loh/treeprogs/guide/guideman.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Loh, W.Y. Classification and Regression Tree Methods; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Audet, J. Evaluation of two approaches to entrepreneurship education using an intention-based model of venture creation. Acad. Entrep. J. 2000, 6, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Boissin, J.P.; Branchet, B.; Emin, S.; Herbert, J.I. Students and entrepreneurship: A comparative study of France and the United States. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2009, 22, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ozaralli, N.; Rivenburgh, N.K. Entrepreneurial intention: Antecedents to entrepreneurial behavior in the USA and Turkey. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2016, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zabelina, E.; Deyneka, O.; Tsiring, D. Entrepreneurial attitudes in the structure of students’ economic minds. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neneh, B.N. From entrepreneurial intentions to behavior: The role of anticipated regret and proactive personality. J. Voc. Behav. 2019, 112, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R. Predicting entrepreneurial intention across the university. Educ. Train. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palalić, R.; Ramadani, V.; Đilović, A.; Dizdarević, A.; Ratten, V. Entrepreneurial intentions of university students: A case-based study. J. Entrep. Commun. People Places Glob. Econ. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ni, H.; Ye, Y. Factors influencing entrepreneurial intentions of Chinese secondary school students: An empirical study. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2016, 17, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Do, T.H.H.; Vu, T.B.T.; Dang, K.A.; Nguyen, H.L. Factors affecting entrepreneurial intentions among youths in Vietnam. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 99, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K.; Sharifi-Tehrani, M.; Pratt, S.; Altinay, L. Understanding entrepreneurial intentions: A developed integrated structural model approach. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farrukh, M.; Alzubi, S.A.; Waheed, A.; Kanwal, N. Entrepreneurial intentions: The role of personality traits in perspective of theory of planned behavior. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sher, A.; Adil, S.A.; Mushtaq, K.; Ali, A.; Hussain, M. An investigation of entrepreneurial intentions of agricultural students. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 54, 941–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, I.A.; Amjed, S.; Jaboob, S. The moderating role of entrepreneurship education in shaping entrepreneurial intentions. J. Econ. Struct. 2020, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vuorio, A.M.; Puumalainen, K.; Fellnhofer, K. Drivers of entrepreneurial intentions in sustainable entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Padilla-Angulo, L. Student associations and entrepreneurial intentions. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Republic of Serbia Year | Doing Business Rank | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 44/190 | [36] |

| 2019 | 48/190 | [37] |

| 2018 | 43/190 | [38] |

| 2017 | 47/190 | [39] |

| 2016 | 59/189 | [40] |

| 2015 | 91/189 | [41] |

| 2014 | 93/189 | [42] |

| 2013 | 86/185 | [43] |

| 2012 | 92/183 | [44] |

| 2011 | 89/183 | [45] |

| 2010 | 90/183 | [46] |

| 2009 | 94/181 | [47] |

| Research Parameter | Information |

|---|---|

| Number of participants | 5670 (n = 5670) |

| Research duration | 2009–2018 (finalized in 2019) |

| Sample structure | high school students; students enrolled in management and business courses |

| Material for data collection | structured survey (presented in Table A1.) |

| Data analysis | descriptive statistics; Chi-square; Welch’s t-test; binary logistic regression; decision tree with the QUEST algorithm |

| QUEST: predictor variable type | nominal/category; ordinal; quantitative |

| QUEST: number of branches | Two |

| QUEST: Branching variable | Single or multiple predictors |

| QUEST: Splitting rule | F/Chi-square test; ANOVA |

| QUEST: Tree pruning | Cross validation |

| Year Pair | Welch’s t-Test Result p(T ≤ t) Two-Tail (Alpha 0.05) | Year Pair | Chi-Square Result Observed Value; Critical Value; p-Value (df = 1, Alpha 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009–2010 | 0.561 | 2009–2010 | 2.562; 3.841; 0.109 |

| 2010–2011 | 0.440 | 2010–2011 | 8.062; 3.841; 0.0045 |

| 2011–2012 | 0.725 | 2011–2012 | 11.825; 3.841; 0.001 |

| 2012–2013 | 0.100 | 2012–2013 | 2.144; 3.341; 0.143 |

| 2013–2014 | 0.646 | 2013–2014 | 0.795; 3.841; 0.037 |

| 2014–2015 | 0.602 | 2014–2015 | 7.622; 3.841; 0.007 |

| 2015–2016 | 0.733 | 2015–2016 | 0.923; 3.841; 0.337 |

| 2016–2017 | 0.795 | 2016–2017 | 7.505; 3.841; 0.0062 |

| 2017–2018 | 0.614 | 2017–2018 | 0.017; 3.841; 0.83 |

| Year Pair | z-Test (z Stat; z Critical Two-Tail) |

|---|---|

| 2009–2010 | −1.290; 1.960 |

| 2010–2011 | −0.888; 1.960 |

| 2011–2012 | −0.621; 1.960 |

| 2012–2013 | 1.806; 1.960 |

| 2013–2014 | 0.716; 1.960 |

| 2014–2015 | 0.452; 1.960 |

| 2015–2016 | −0.811; 1.960 |

| 2016–2017 | 0.513; 1.960 |

| 2017–2018 | −0.907; 1.960 |

| Independent Variables (Viewed as Predictor Groups) | Dependent Variable (Viewed as a Predictor Group) | Standardized Coefficients | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close social environment | Entrepreneurial intentions | 0.118 | 0.855 |

| Attitudes | −0.329 | 0.000 | |

| Environment assessment | −0.095 | 0.771 | |

| Awareness of incentive means | 0.110 | 0.701 |

| Predictor Item | β | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.04 | 0.001 | 1.01 | 1.06 |

| A private enterprise is more successful compared to other types of business | 1.38 | 0.000 | 1.29 | 1.46 |

| In Serbia, people do not know the real opportunities in the domain of private enterprises | 1.20 | 0.000 | 1.12 | 1.27 |

| A private enterprise is not profitable and it is uncertain | 0.69 | 0.000 | 0.64 | 0.72 |

| The working conditions in a private enterprise are better than in other types of business | 1.10 | 0.000 | 1.04 | 1.15 |

| Do you have a member of family who owns a private enterprise? | 0.83 | 0.009 | 0.72 | 0.95 |

| Do you think that start-up loans from business banks are affordable for young entrepreneurs? | 0.81 | 0.003 | 0.70 | 0.93 |

| Are you familiar with the existence of incentive means for starting a business? | 0.39 | 0.000 | 0.34 | 0.44 |

| Do you think that there is a good entrepreneurial environment in Serbia to start a business? | 0.84 | 0.072 | 0.69 | 1.01 |

| Do you think that the government should have a key role in stimulating the youth to start their own enterprise? | 0.86 | 0.168 | 0.70 | 1.06 |

| Close Social Environment | Attitudes | Environment Assessment | Awareness of Incentive Means | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | 0.524 | 0.363 | 0.377 | 0.390 |

| Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) | 1.842 | 2.011 | 2.068 | 2.429 |

| Predictor | Coef. | Std. Err. | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.444 | 2.45 | 0.014 |

| Gender | −0.849 | 0.105 | 0.417 |

| Close social environment | 1.950 | 1.112 | 0.049 |

| Attitudes | −0.443 | 0.279 | 0.012 |

| Awareness of incentive means | 0.855 | 2.170 | 0.030 |

| Environment assessment | −0.085 | 0.104 | 0.382 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Djordjevic, D.; Cockalo, D.; Bogetic, S.; Bakator, M. Predicting Entrepreneurial Intentions among the Youth in Serbia with a Classification Decision Tree Model with the QUEST Algorithm. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1487. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9131487

Djordjevic D, Cockalo D, Bogetic S, Bakator M. Predicting Entrepreneurial Intentions among the Youth in Serbia with a Classification Decision Tree Model with the QUEST Algorithm. Mathematics. 2021; 9(13):1487. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9131487

Chicago/Turabian StyleDjordjevic, Dejan, Dragan Cockalo, Srdjan Bogetic, and Mihalj Bakator. 2021. "Predicting Entrepreneurial Intentions among the Youth in Serbia with a Classification Decision Tree Model with the QUEST Algorithm" Mathematics 9, no. 13: 1487. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9131487

APA StyleDjordjevic, D., Cockalo, D., Bogetic, S., & Bakator, M. (2021). Predicting Entrepreneurial Intentions among the Youth in Serbia with a Classification Decision Tree Model with the QUEST Algorithm. Mathematics, 9(13), 1487. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9131487