Models of Set Theory in which Nonconstructible Reals First Appear at a Given Projective Level

Abstract

1. Introduction

the central problem of descriptive set theory and definability theory in general [is] to find and study the characteristic properties of definable objects.

- (i)

- there is a nonconstructible set , but all sets are constructible and in

- (ii)

- we can strengthen (i) by the requirement that in the extension.

- A model defined in [17], in which, for a given , there is a (lightface) Vitali equivalence class in the real line (that is, a set of the form in ), containing no OD (ordinal definable) elements, and in the same time every countable set consists of OD elements.

- A model in [18], in which, for a given , there is a singleton , such that a codes a collapse of , and in the same time every set is still constructible.

- A model defined in [19], in which, for a given , there is a non-OD-uniformizable planar set with countable cross-sections, and at the same time, every set with countable cross-sections is OD-uniformizable.

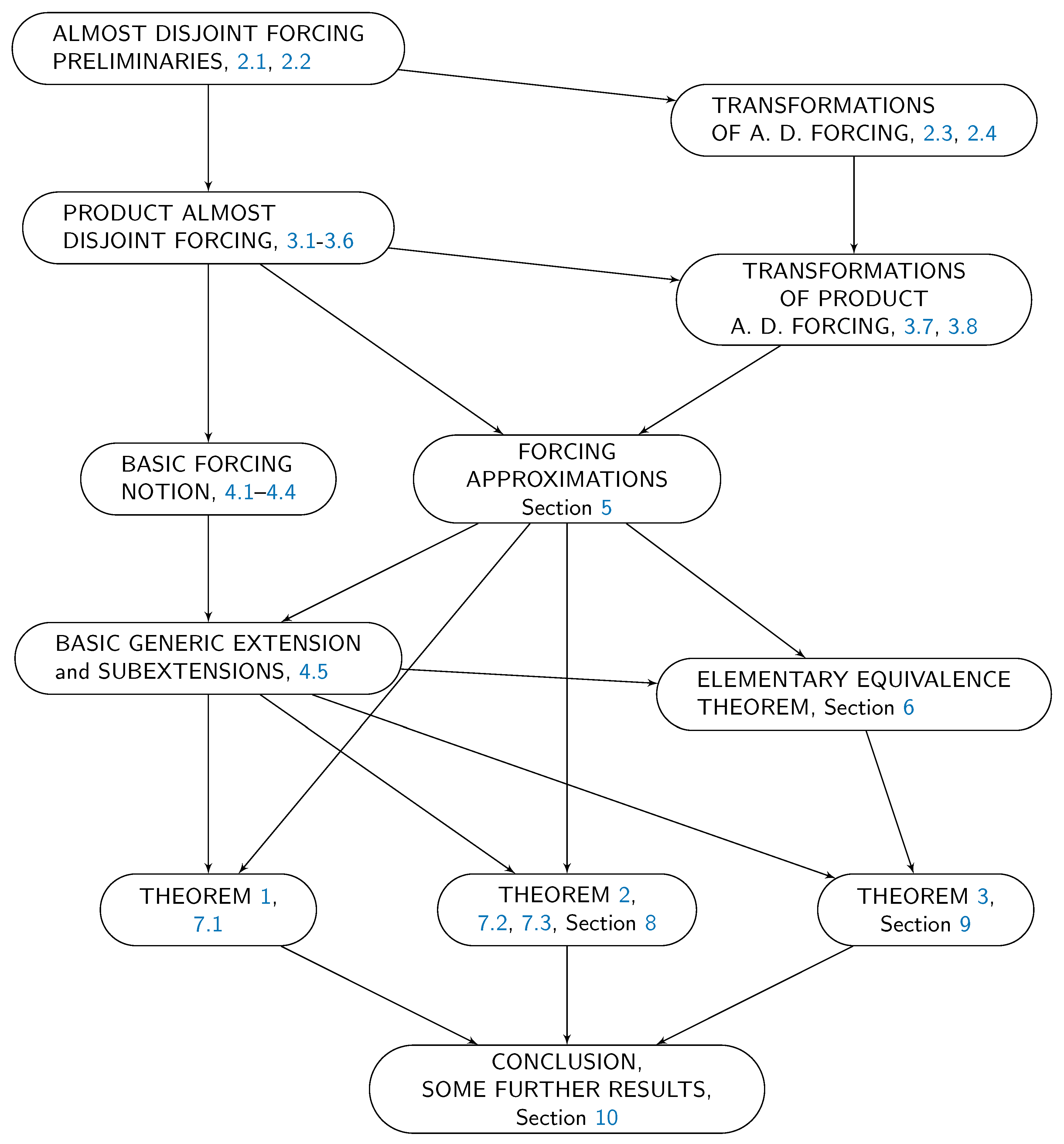

Organization of the Paper

- are sufficiently homogeneous and independent of each other in the sense that, for any , there are no -generic reals in a -generic extensions of .

- The property of a real x being -generic over is as a binary relation, where is a number chosen in Theorems 1–3.

- A condition which makes -generic reals for different values undistinguishable from each other below the definability level (at which they are distinguishable by condition 2).

General Set-Theoretic Notation Used in This Paper

- natural numbers; .

- iff the inclusion.

- means that but strict inclusion.

- is the cardinality of a set equal to the number of elements of X in case X is finite.

- = and = — thedomain and range of any set P that consists of pairs.

- In particular if is a function then and are the domain and the range of f.

- Functions are identified with their graphs: if is a function then so that is equivalent to .

- , the -image of X.

- , the -pre-image of a set Y.

- , the - pre-image of an element y.

- is the symmetric difference.

- is the map f defined on A by .

- , the power set.

- is the set of all strings (finite sequences) of elements of a set

- In particular is the set of strings of natural numbers.

- is the length of a string s.

- is the string obtained by adjoining x as the rightmost term to a given string

- means that the string t is a proper extension of s.

- is resp. the empty set and the empty string.

- is the Baire space.

2. Almost Disjoint Forcing

2.1. Almost Disjoint Forcing

2.2. Almost-Disjoint Generic Extensions

- (i)

- G belongs to

- (ii)

- if then iff does not cover

- (iii)

- if then iff .

2.3. Lipschitz Transformations

- –

- finite strings by: ;

- –

- functions : is defined so that ;

- –

- sets by: , ;

- –

- conditions , by: .

- (∗)

- if then and , but if then .

2.4. Substitution Transformations

3. Almost Disjoint Product Forcing

3.1. Product Forcing, Systems, Restrictions

- disjoint, if its components are pairwise disjoint;

- countable, if the set and each are at most countable.

- If are systems, , and for all then we write that V extends U, in symbol .

- If is a sequence of systems then define a system by and for all .

- If U is a system then let be the finite support product of sets , that is,

3.2. Regular Forcing Notions

- (1)

- if conditions are compatible then ;

- (2)

- if then — but it is not assumed that necessarily implies for an arbitrary ;

- (3)

- if , , and exactly, then implies ;

- (4)

- for any condition , there exist: a condition and a set such that , for all , for all , , and every condition , satisfies , and hence q is compatible with and with p.

3.3. Outline of Product and Regular Extensions

- (i)

- (ii)

- the set is -generic over

- (iii)

- , where (it is not necessary that !);

- (iv)

- if then

- (v)

- if then

- (vi)

- if then the set is -generic over , hence if then .

3.4. Names for Sets in Product and Regular Extensions

3.5. Names for Functions

3.6. Names and Sets in Generic Extensions

- (i)

- if and φ is a closed formula with -names as parameters, then

- (ii)

- if are countable sets in , and , then there is a -full name in such that .

- (iii)

- if , then there is a name in such that , and in addition if X is countable in then .

- (iv)

- if are countable sets in , , is a formula with -names as parameters, and , then there is a -full name in such that .

3.7. Transformations Related to Product Forcing

- –

- sets : — then and ;

- –

- systems U with : for all — then ;

- –

- conditions with : for all ;

- –

- sets : — then , in particular, for any regular subforcing ;

- –

- names : — then

- –

- systems U: and ;

- –

- conditions , by and ;

- –

- sets : , in particular, for any regular subforcing ;

- –

- names : ;

- (i)

- , , and

- (ii)

- there are conditions and such that —in particular, conditions and q are compatible in .

3.8. Substitutions and Homogeneous Extensions

- If are any sets and is a name below p then put , so is a name below q.

- If is a formula with names below p as parameters then denotes the result of substitution of for any name in .

- (i)

- if and then

- (ii)

- in particular, for (and ), Q decides any formula Φ which contains only names for sets in and names via of the form with , as parameters;

- (iii)

- if and then .

4. Basic Forcing Notion and Basic Generic Extension

4.1. Jensen–Solovay Sequences

- (a)

- the set (note the union over rather than !) is multiply Cohen generic over M, in the sense that every string of pairwise different functions is Cohen generic over M, and

- (b)

- if and then is dense in .

- iff and ;

- iff and .

4.2. Stability of Dense Sets

- (i)

- (ii)

- , where is -generic over and is a PO set;

- (iii)

- , where is finite, is fixed, and .

- (∗)

- , where ,

- (†)

- , where .

- (‡)

- , where each is finite.

4.3. Digression: Definability in

- = all sets , definable in by a parameter-free formula.

- = all sets definable in by a formula with sets in as parameters.

4.4. Complete Sequences and the Basic Notion of Forcing

- (i)

- and

- (ii)

- if then is uncountable and topologically dense in , and if belong to then is empty;

- (iii)

- any set , pre-dense in (resp., pre-dense in below some ), is pre-dense in (resp., pre-dense in below p);

- (iv)

- any name , -full (resp., -full below some ), is -full (resp., -full below p);

- (v)

- if is a set -generic over the ground universe then the set is -generic over .

4.5. Basic Generic Extension and Regular Subextensions

- (i)

- if , then and holds, but

- (ii)

- if , then , and there is no sets in satisfying .

- (i)

- is equal to the set

- (ii)

- it is true in that the set is

- (iii)

- therefore is in .

5. Forcing Approximations

5.1. Models and Absolute Sets

5.2. Formulas

5.3. Forcing Approximation

- (F1)

- Writing , it is assumed that:

- (a)

- ,

- (b)

- is a regular forcing and an absolute set,

- (c)

- p belongs to (a regular subforcing of by Lemma 7),

- (d)

- φ is a closed formula in for some , and each name is -full below p.

- (F2)

- If , and φ is a closed formula in (then by definition it has no quantifier indices), then: iff (F1) holds and p -forces φ over M in the usual sense. Note that the forcing notion belongs to M in this case by (F1)b.

- (F3)

- If , then:

- (a)

- iff there is a name , -full below p (by (F1)d) and such that .

- (b)

- iff there is a name , -full below p (by (F1)d) and such that .

- (F4)

- If , φ is a closed formula, , and (F1) holds, then iff we have for every pair extending , and every condition , where is the result of canonical conversion of to .

- (i)

- if , and , then

- (ii)

- if , φ is , and , then fails.

- (i)

- and are

- (ii)

- if then and are .

5.4. Advanced Properties of Forcing Approximations

5.5. Transformations and Invariance

- –

- to get substitute for any and for any .

- –

- to get substitute for any but do not change the quantifier indices B.

6. Elementary Equivalence Theorem

6.1. Further Properties of Forcing Approximations

- (i)

- if and , , then

- (ii)

- and contradict to each other;

- (iii)

- if φ is a formula, is a maximal antichain in Q, and for all , then

- (i)

- there is , such that or

- (ii)

- if φ is , then iff there is no condition , such that

6.2. Relations to the Truth in Generic Extensions

- (i)

- if and , then is true in

- (ii)

- conversely, if is true in and strictly holds, then .

6.3. Consequences for the Ordinary Forcing Relation

- (i)

- if φ is or and , then

- (ii)

- if φ is , then iff

- (iii)

- if strictly, φ belongs to or , and , then

- (iv)

- if strictly, φ is , and then

- (i)

- if φ belongs to , , then the following set is

- (ii)

- similarly, if φ is , then is .

6.4. Elementary Equivalence Theorem

7. Application 1: Nonconstructible Reals

7.1. Changing Definability of an Old Real

7.2. Nonconstructible Real, Part 1

- (A)

- if then

- (B)

- if then —and hence by (A).

7.3. Nonconstructible Real, Part 2

8. Application 2: Nonconstructible Self-Definable Reals

8.1. Nonconstructible Self-Definable Reals: The Model

- Each set is countably infinite, , and , and finally each is equal to for exactly one pair of indices of .

- (1)

- ;

- (2)

- if then, for every i: if then and , butif then, for every i: if then and ;

- (3)

- if then for all i.

- (i)

- ζ is

- (ii)

- if is , then and x is in .

- (A)

- if then

- (B)

- if then —and hence by (A).

- (a)

- or , and

- (b)

- (to make sure that ).

- (1)

- , if and ;

- (2)

- , if and .

- (a)

- , and if then and for all i;

- (b)

- if then we have iff for every i, and

- (c)

- if then the set satisfies .

8.2. Key Lemma

8.3. Matching Permutation

- (I)

- a sequence of numbers , such that and, for any m, is the least (in the usual order of ) -minimal element of , where ,—then and each is a -initial segment of ;

- (II)

- for every m, a transformation , such that is the identity for all but , and a matching permutation by Claim 7 — thus is the identity outside of the cone ;

- (III)

- a -preserving superposition , equal to the identity outside of the extended ≪-cone , in the sense that if U is a system with , or a condition satisfies , then and for all .

8.4. Final Argument

- –

- so that , but is the identity, whenever ;

- –

- as in assumption (II) of Section 8.3 — thus is the identity outside of ;

- –

- a -preserving superposition , equal to the identity outside of the extended cone , as in assumption (III) of Section 8.3.

9. Application 3: Nonconstructible Reals

9.1. Nonconstructible Reals: The Model

9.2. Key Lemma

- (∗)

- if then satisfies , for all , and even , but .

9.3. Second Key Lemma

- (I)

- is -generic over , , and are parameter-free formulas that give a definition for in .

- (II)

- .

- (1°)

- the sentence “” is -decided by .

- (2°)

- and .

- (a)

- and . (= (3) in Section 3.8.)

- (b)

- the symmetric difference contains a single element .

9.4. Final Argument

10. Conclusions and Some Further Results

10.1. Separation

In fact (we believe) there is a model of in which Separation fails for all of the following at once: , , , , , , . ( , are classes arising in the type-theoretic hierarchy).

- (i)

- there exist disjoint sets of reals unseparable by disjoint sets,

- (ii)

- there exist disjoint sets of reals unseparable by disjoint sets.

10.2. Projections of Uniform Sets

- Projection problem:

- given , find out the nature of projections of uniform (planar) sets in comparison with the class of arbitrary projections of sets and with the narrower class . (A planar set is uniform, if it intersects every vertical line at no more than one point.)

- (i)

- there is a set not equal to the projection of a uniform sets,

- (ii)

- there is a set not equal to the projection of a uniform set.

10.3. Harvey Friedman’s Problem

10.4. Axiom Schemata in 2nd Order Arithmetic

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hadamard, J.; Baire, R.; Lebesgue, H.; Borel, E. Cinq lettres sur la théorie des ensembles. Bull. Soc. Math. Fr. 1905, 33, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antos, C.; Friedman, S.; Honzik, R.; Ternullo, C. (Eds.) The Hyperuniverse Project and Maximality; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2018; p. XI, 265. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, S.D.; Schrittesser, D. Projective Measure without Projective Baire; Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society; AMS: Providence, RI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, S.D.; Hyttinen, T.; Kulikov, V. Generalized Descriptive Set Theory and Classification Theory; Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society; AMS: Providence, RI, USA, 2014; Volume 1081, p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, S.G. Subsystems of Second Order Arithmetic, 2nd ed.; Perspectives in Logic; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; ASL: Urbana, IL, USA, 2009; p. 444. [Google Scholar]

- Moschovakis, Y.N. Descriptive Set Theory; Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1980; Volume 100, p. 637. [Google Scholar]

- Shoenfield, J.R. The problem of predicativity. In Essays Found. Math., Dedicat. to A. A. Fraenkel on his 70th Anniv.; Bar-Hillel, Y., Ed.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1962; pp. 132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Mathias, A.R.D. Surrealist landscape with figures (a survey of recent results in set theory). Period. Math. Hung. 1979, 10, 109–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R.B.; Solovay, R.M. Some applications of almost disjoint sets. In Math. Logic Found. Set Theory, Proc. Int. Colloqu. Jerusalem 1968; Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics; Bar-Hillel, Y., Ed.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1970; Volume 59, pp. 84–104. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, R.B. Definable sets of minimal degree. In Math. Logic Found. Set Theory, Proc. Int. Colloqu. Jerusalem 1968; Studies in Logic and the Foundations of, Mathematics; Bar-Hillel, Y., Ed.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1970; Volume 59, pp. 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, S.D. Provable -singletons. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1995, 123, 2873–2874. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, L.; Kechris, A.S. singletons and 0#. Fundam. Math. 1977, 95, 167–171. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, M.C. A singleton incompatible with 0#. Ann. Pure Appl. Logic 1994, 66, 27–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kanovei, V.G. On the nonemptiness of classes in axiomatic set theory. Math. USSR Izv. 1978, 12, 507–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enayat, A. On the Leibniz – Mycielski axiom in set theory. Fundam. Math. 2004, 181, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, U. Minimal model of “ is countable” and definable reals. Adv. Math. 1985, 55, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. Definable E0 classes at arbitrary projective levels. Ann. Pure Appl. Logic 2018, 169, 851–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. Definable minimal collapse functions at arbitrary projective levels. J. Symb. Log. 2019, 84, 266–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. Non-uniformizable sets with countable cross-sections on a given level of the projective hierarchy. Fundam. Math. 2019, 245, 175–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwise, J. (Ed.) Handbook of Mathematical Logic. In Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977; Volume 90. [Google Scholar]

- Jech, T. Set Theory; The Third Millennium Revised and Expanded Edition; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2003; p. 769. [Google Scholar]

- Kanovei, V.G. Projective hierarchy of Luzin: Modern state of the theory. In Handbook of Mathematical Logic. Part 2. Set Theory. (Spravochnaya Kniga Po Matematicheskoj Logike. Chast’ 2. Teoriya Mnozhestv); Transl. from the English; Barwise, J., Ed.; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1982; pp. 273–364. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, R.B.; Johnsbraten, H. A new construction of a non-constructible subset of ω. Fundam. Math. 1974, 81, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gitman, V.; Hamkins, J.D.; Johnstone, T.A. What is the theory ZFC without power set? Math. Log. Q. 2016, 62, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusin, N. LeÇons Sur Les Ensembles Analytiques Et Leurs Applications; Gauthier-Villars: Paris, France, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Novikoff, P. Sur les fonctions implicites mesurables B. Fundam. Math. 1931, 17, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Novikoff, P. Sur la séparabilité des ensembles projectifs de seconde classe. Fundam. Math. 1935, 25, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Addison, J.W. Separation principles in the hierarchies of classical and effective descriptive set theory. Fundam. Math. 1959, 46, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Addison, J.W. Some consequences of the axiom of constructibility. Fundam. Math. 1959, 46, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.D. Constructibility and class forcing. In Handbook of Set Theory; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; Volume 3, pp. 557–604. [Google Scholar]

- Hinman, P.G. Recursion-Theoretic Hierarchies; Perspectives in Mathematical Logic; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1978; p. 480. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, L. The constructible reals can be anything. Preprint dated May 1974 with several addenda dated up to October 1975: (A) Models where Separation principles fail, May 74; (B) Separation without Reduction, April 75; (C) The constructible reals can be (almost) anything, Part II, May 75.

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. Counterexamples to countable-section uniformization and separation. Ann. Pure Appl. Logic 2016, 167, 262–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V. Non-Glimm-Effros equivalence relations at second projective level. Fund. Math. 1997, 154, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kanovei, V. An Ulm-type classification theorem for equivalence relations in Solovay model. J. Symb. Log. 1997, 62, 1333–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V. On non-wellfounded iterations of the perfect set forcing. J. Symb. Log. 1999, 64, 551–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.G.N.N. Luzin’s problems on imbeddability and decomposability of projective sets. Math. Notes 1983, 32, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H. One hundred and two problems in mathematical logic. J. Symb. Log. 1975, 40, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.G. The set of all analytically definable sets of natural numbers can be defined analytically. Math. USSR Izvestija 1980, 15, 469–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, R. reals. Ann. Math. Logic 1982, 23, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreisel, G. A survey of proof theory. J. Symb. Log. 1968, 33, 321–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, A. Definability in axiomatic set theory II. In Math. Logic Found. Set Theory, Proc. Int. Colloqu. Jerusalem 1968; Bar-Hillel, Y., Ed.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1970; pp. 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, S.D.; Gitman, V.; Kanovei, V. A model of second-order arithmetic satisfying AC but not DC. J. Math. Log. 2019, 19, 39, Id/No 1850013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrascano, P.; Callegari, S.; Montisci, A.; Ricci, M.; Versaci, M. (Eds.) Ultrasonic Nondestructive Evaluation Systems; Springer International Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2015; p. XXXIII, 324. [Google Scholar]

- Versaci, M. Fuzzy approach and Eddy currents NDT/NDE devices in industrial applications. Electron. Lett. 2016, 52, 943–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. Models of Set Theory in which Nonconstructible Reals First Appear at a Given Projective Level. Mathematics 2020, 8, 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/math8060910

Kanovei V, Lyubetsky V. Models of Set Theory in which Nonconstructible Reals First Appear at a Given Projective Level. Mathematics. 2020; 8(6):910. https://doi.org/10.3390/math8060910

Chicago/Turabian StyleKanovei, Vladimir, and Vassily Lyubetsky. 2020. "Models of Set Theory in which Nonconstructible Reals First Appear at a Given Projective Level" Mathematics 8, no. 6: 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/math8060910

APA StyleKanovei, V., & Lyubetsky, V. (2020). Models of Set Theory in which Nonconstructible Reals First Appear at a Given Projective Level. Mathematics, 8(6), 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/math8060910