Abstract

In this paper, we prove the following. If , then there is a generic extension of , the constructible universe, in which it is true that the set of all constructible reals (here—subsets of ) is equal to the set of all (lightface) reals. The result was announced long ago by Leo Harrington, but its proof has never been published. Our methods are based on almost-disjoint forcing. To obtain a generic extension as required, we make use of a forcing notion of the form in , where adds a generic collapse surjection b from onto , whereas each , , is an almost-disjoint forcing notion in the -version, that adjoins a subset of . The forcing notions involved are independent in the sense that no -generic object can be added by the product of and all , . This allows the definition of each constructible real by a formula in a suitably constructed subextension of the -generic extension. The subextension is generated by the surjection b, sets with , and sets with . A special character of the construction of forcing notions is , which depends on a given , obscures things with definability in the subextension enough for vice versa any real to be constructible; here the method of hidden invariance is applied. A discussion of possible further applications is added in the conclusive section.

Keywords:

Harvey Friedman’s problem; definability; nonconstructible reals; projective hierarchy; generic models; almost-disjoint forcing MSC:

03E15; 03E35

1. Introduction

Problem 87 in Harvey Friedman’s treatise One hundred and two problems in mathematical logic [1] requires proof that for each n in the domain there is a model of

(For this is definitely impossible e.g., by the Shoenfield’s absoluteness theorem.) This problem was generally known in the early years of forcing, see, e.g., problems 3110, 3111, 3112 in an early survey [2] (the original preprint of 1968) by Mathias. At the very end of [1], it is noted that Leo Harrington had solved this problem affirmatively. For a similar remark, see [2] (p. 166), a comment to P 3110. And indeed, Harrington’s handwritten notes [3] (pp. 1–4) contain a sketch of a generic extension of , based on the almost-disjoint forcing of Jensen and Solovay [4], in which it is true that . Then a few sentences are added on page 5 of [3], which explain, as how Harrington planned to get a model in which holds for a given (arbitrary) natural index , and a model in which , where (all analytically definable reals). This positively solves Problem 87, including the case . Different cases of higher order definability are observed in [3] as well.

Yet no detailed proofs have ever emerged in Harrington’s published works. An article by Harrington, entitled “Consistency and independence results in descriptive set theory”, which apparently might have contained these results among others, was announced in the References list in Peter Hinman’s book [5] (p. 462) to appear in Ann. of Math., 1978, but in fact, this or similar article has never been published by Harrington.

One may note that finding a model for (1) belongs to the “definability of definable” type of mathematical problems, introduced by Alfred Tarski in [6], where the definability properties of the set , of all sets definable by a parameter-free type-theoretic formula with quantifiers bounded by type M, are discussed for different values of . In this context, case in (1) is equivalent to case in the Tarski problem, whereas cases in (1) can be seen as refinements of case in the Tarski problem, because classes are well-defined subclasses of .

The goal of this paper is to present a complete proof of the following part of Harrington’s statement that solves the mentioned Friedman’s problem. No such proof has been known so far in mathematical publications, and this is the motivation for our research.

Theorem 1

(Harrington). If then there is a generic extension of in which it is true that the constructible reals are precisely the reals.

The case of Harrington’s result, as well as different results related to Tarski’s problems in [6], will be subject of a forthcoming publication.

This paper is dedicated to the proof of Theorem 1. This will be another application of the technique introduced in our previous paper [7] in this Journal, and in that sense this paper is a continuation and development of the research started in [7]. However, the problem considered here, i.e., getting a model for (1), is different from and irreducible to the problems considered in [7] and related to definability and constructability of individual reals. Subsequently the technique applied in [7] is considerably modified and developed here for the purposes of this new application. In particular, as the models involved here by necessity satisfy (unlike the models considered in [7], which satisfy the equality ), the almost-disjoint forcing is combined with a cardinal collapse forcing in this paper. And hence we will have to substantially deviate from the layout in [7], towards a modification that shifts the whole almost-disjoint machinery from to .

Section 2: we set up the almost-disjoint forcing in the -version. That is, we consider the sets and in , the constructible universe, and, given , we define a forcing notion which adds a set such that if in then G covers f iff , where covering means that for unbounded-many . We also consider two types of transformations related to forcing notions of the form .

Section 3. We let be the index set. Arguing in , we consider systems , where each is dense. Given such U, the product almost-disjoint forcing (with finite support) is defined in , where is a version of Cohen’s collapse forcing. Such a forcing notion adjoins a generic map to , and adds an array of sets (where ) as well, so that each is a -generic set over . We also investigate the structure of related product-generic extensions and their subextensions, and transformations of forcing notions of the form .

Section 4. Given , we define a system as above, which has some remarkable properties, in particular, (1) being -generic is essentially a property in all suitable generic extensions, (2) if and is generic over , then the extension contains no -generic reals, and (3) all submodels of of certain kind are elementarily equivalent w. r. t. formulas. The latter property is summarized in the key technical instrument, Theorem 4 (the elementary equivalence theorem), whose proof is placed in a separate Section 6. To prove Theorem 1, we make use of a related generic extension , where

(see Lemma 23), and · is the ordinal multiplication. The first term in provides a suitable definition of each set in the model , namely

while the second and third terms in are added for technical reasons. The proof itself goes on in Section 4.5, modulo Theorem 4.

We introduce forcing approximations in Section 5, a forcing-like relation used to prove the elementary equivalence theorem. Its key advantage is the invariance under some transformations, including the permutations of the index set , see Section 5.4. The actual forcing notion is absolutely not invariant under permutations, but the -completeness property, maintained through the inductive construction of in , allows us to prove that the auxiliary forcing relation is connected to the truth in -generic extensions exactly as the true -forcing relation does—up to the level of the projective hierarchy (Lemma 33). We call this construction the hidden invariance technique (see Section 6.1).

Finally, Section 6 presents the proof of the elementary equivalence theorem, with the help of forcing approximations, and hence completes the proof of Theorem 1.

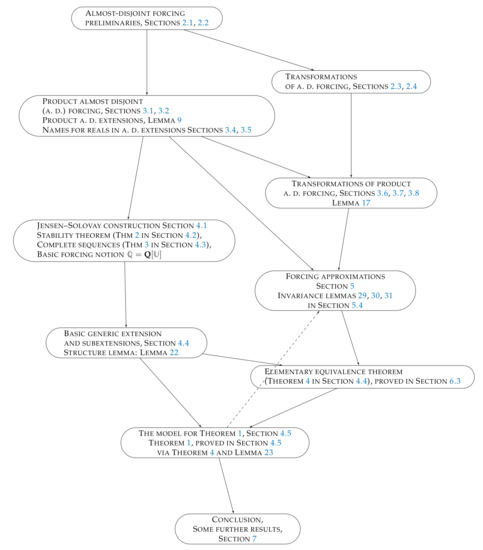

The flowchart can be seen in Figure 1 on page 3. And we added the index and contents as Supplementary Materials for easy reading.

Figure 1.

Flowchart.

2. Almost-Disjoint Forcing

Almost-disjoint forcing as a set theoretic tool was invented by Jensen and Solovay [4]. It has been applied in many research directions in modern set theory, in particular, in our paper [7] in this Journal. Here we make use of a considerably different version of the almost-disjoint forcing technique, which, comparably to [7], (1) considers countable cardinality instead of finite cardinalities in some key positions, (2) accordingly considers cardinality instead of countable cardinality. In particular, sequences of finite length change to those of length . And so on.

Assumption 1.

During arguments in this section, we assume that the ground set universe is , the constructible universe. Recall that in , and . □

For the sake of brevity, we call -size sets those X satisfying .

2.1. Almost-Disjoint Forcing: -Version

This subsection contains a review the basic notation related to almost-disjoint forcing in the - version. Arguing in , we put = all -sequences of ordinals .

- A set is dense iff for any there is such that .

- We let , the set of all non-empty sequencess of ordinals , of length . We underline that , the empty sequence, does not belong to .

- If then let . If is unbounded in then say that S covers f, otherwise S does not cover f.

The following or very similar version of the almost-disjoint forcing was defined by Jensen and Solovay in [4] ([§ 5]). Its goal can be formulated as follows: given a set in the ground universe, find a generic set such that the equivalence

holds for each in the ground universe.

Definition 1 (in ).

is the set of all pairs of finite sets , . Elements of will be called (forcing) conditions. If then put

a tree in . If then let ; a condition in .

Let . Define (that is, q is stronger as a forcing condition) iff , and the difference does not intersect , i.e., . Clearly, we have iff , and . □

Lemma 1 (in ).

Conditions are compatible in iff does not intersect , and does not intersect . Therefore any are compatible in iff and .

Proof.

If (1), (2) hold then and , thus are compatible. □

If then put .

Any conditions are compatible in iff they are compatible in iff the condition satisfies both and . Therefore, we can say that conditions are compatible (or incompatible) without an explicit indication which forcing notion containing is considered.

Lemma 2 (in ).

If and is an antichain then .

Proof.

Suppose towards the contrary that . If in A are incompatible then obviously . Yet all finite subsets of , is a set of cardinality , a contradiction. □

2.2. Almost-Disjoint Generic Extensions

To work with -sets and in generic extensions of , possibly in those obtained by means of cardinal collapse, we let

—in other words, and are just and defined in .

Lemma 3.

Suppose that in , is dense. Let be a set -generic over . We define thus . Then

- (i)

- if then iff does not cover

- (ii)

- if then iff .

- (iii)

- (iv)

- if then is a cofinal subset of of order type

- (v)

- .

Proof.

(i) Consider any . We claim that is dense in . (Indeed if then define by and ; we have and .) It follows that . Choose any ; we have . Each condition is compatible with p, therefore, by Lemma 1, . We conclude that .

Now assume that . The set is dense in for any . (Let . Then is finite. There exists with , since . Define a condition p by and ; we have and .) Pick, by the density, any . Then . We conclude that is infinite because l is arbitrary.

(ii) Let . Then obviously . If there exists then for some . Then conditions are incompatible by Lemma 1, which is a contradiction.

Now assume that . There is a condition incompatible with p. We have two cases by Lemma 1. First, there is some . Then , so p is not compatible with . Second, there is some . In this case, holds for any condition . It follows that , hence , and p cannot be compatible with .

Further it follows from (ii) that , hence, we have (iii). Claim (v) is an immediate corollary of (iv) since remains a cardinal in by Lemma 2.

Finally, to prove (iv) let and . The set of all conditions , such that for some , is dense in . Therefore G contains some . Let this be witnessed by some . Now, if belongs to , so that , then s must belong to by (ii), therefore belongs to the finite set . Thus, is finite. That is infinite follows from (i) (recall that ). □

Now we consider two types of transformations related to the forcing notion .

2.3. Lipschitz Transformations

We argue in . Let be the group of all -automorphisms of , called Lipschitz transformations. Any preserves the length of sequences, i.e., for all . Any transformation acts on:

- –

- sequences : by ;

- –

- functions : by and for all ;

- –

- sets : by , ;

- –

- conditions : by .

Lemma 4 (routine).

The action of any is an order-preserving automorphism of If and then . □

We proceed with an important existence lemma. If belongs to then let be equal to the least ordinal such that (or, similarly, the largest ordinal with ). Say that sets are intersection-similar, or i-similar for brevity, if there is a bijection such that for all in X—such a bijection b will be called an i-similarity bijection.

Lemma 5.

Suppose that are -size sets, dense in . Then are i-similar. Moreover, if , are finite and i-similar then

- (i)

- there is an i-similarity bijection such that ,

- (ii)

- there exists a transformation such that and .

Proof.

The key argument is that if , are at most countable, is an i-similarity bijection, and , then by the density of v there is such that the extended map is still an i-similarity bijection. This allows proof of (i), iteratively extending an initial i-similarity bijection by a -step back-and-forth argument involving eventually all elements and , to an i-similarity bijection required. See the proof of Lemma 5 in [7] for more detail.

To get (ii) from (i), consider any sequence . Let . As u is dense, there exist such that and . Put . Then still , hence . Therefore, we can define . □

2.4. Substitution Transformations

We continue to argue in . Assume that conditions satisfy

We define a transformation acting as follows.

If then define for all , the identity.

Suppose that . Then are incompatible by (4) and Lemma 1. Define ,the domain of . Let . We put , where and

Thus, assuming (4), the difference between and lies entirely within the set , so that if then but , while if then but .

Lemma 6.

(i) If is dense and then there exist conditions with , , satisfying (4).

Proof.

(i) By the density of u there is a finite set satisfying and . Put and . Claims (ii), (iii) are routine. □

Please note that unlike the Lipschitz transformations above, transformations of the form , called substitutions in this paper, act within any given forcing notion of the form by claim (iii) of the lemma, and hence the forcing notions of the form considered are sufficiently homogeneous.

3. Almost-Disjoint Product Forcing

Here we review the structure and basic properties of product almost-disjoint forcing and corresponding generic extensions in the -version. There is an important issue here: a forcing , which collapses to , enters as a factor in the product forcing notions considered.

3.1. Product Forcing

In , we define , the set of all finite sequences of subsets of , an ordinary forcing to collapse down to . We will make use of an -product of with as an extra factor. (In fact, can be eliminated since collapses anyway by Lemma 3 (v). Yet the presence of somehow facilitates the arguments since has a more transparent forcing structure.)

Technically, we put (in ) and consider the index set . Let be the finite-support product of and copies of (Definition 1 in Section 2.1), ordered componentwise. That is, consists of all maps p defined on a finite set so that for all , and if then . If then put and for all , so that .

We order componentwise: (p is stronger as a forcing condition) iff , in case , and in for all . Put

In particular, contains the empty condition satisfying ; obviously ⊙ is the -least (and weakest as a forcing condition) element of .

Because of the factor , it takes some effort to define for , and only assuming that are compatible, i.e., or . In such a case define as follows. First, . If then put , and similarly if then . Now suppose that .

If then in the sense of Definition 1 in Section 2.1.

If , then, by the compatibility, either —and then define , or —and then accordingly .

Lemma 7.

Let be compatible. Then , , , and if , , , then . □

3.2. Systems

Arguing in , we consider certain subforcings of the total product forcing notion .

Let a system be any map such that , each set () is dense in , and the components are pairwise disjoint.

- A system U is small, if both and each set has cardinality .

- If are systems, , and for all , then say that VextendsU, in symbol .

- If is a -increasing sequence of systems then define a system by and for all .

- If U is a system, then is the finite-support product of and sets , i.e.,

Suppose that . If then define so that and whenever . A special case: if then let . Similarly, if U is a system then define a system so that and whenever . A special case: if then let . And if then let (will usually coincide with .

Writing , etc., it is not assumed that .

Lemma 8 (in ).

If U is a system and is an antichain then .

Proof.

Suppose that . As , we can w.l.o.g. assume that for all . It follows by the -system lemma that there is a set of the same cardinality , and a finite set , such that for all . Then we have for all in , easily leading to a contradiction, as in the proof of Lemma 2. □

3.3. Outline of Product Extensions

We consider sets of the form , U being a system in , as forcing notions over . Accordingly, we’ll study -generic extensions of the ground universe . Define some elements of these extensions. Suppose that . Put ;. Let

for any , where .

Thus, , and for any .

By the way, this defines a sequence of subsets of .

If then let . It will typically happen that . Put .

If U is a system in , then any -generic set splits into the family of sets , and a separate map . It will follow from (ii) of the next lemma that -generic extensions of satisfy .

Lemma 9.

Let U be a system in , and be a set -generic over . Then:

- (i)

- is a -generic map from ω onto

- (ii)

- if then and

- (iii)

- and

- (iv)

- if and , , then

- (v)

- if then

- (vi)

- if then the set is -generic over , hence if then iff

Proof.

Proofs of (i) and (iii)–(vi) are similar to ([7] (Lemma 9)). To prove in (ii) apply Lemma 3 (v). Finally, to see that remains a cardinal in apply Lemma 8. □

3.4. Names for Sets in Product Extensions

The next definition introduces names for elements of product-generic extensions of considered.

Assume that in , , e.g., , where U is a system, and X is any set. By (-names for subsets of X) we denote the set of all sets in . Furthermore, (small names) consist of all -size names ; in other words, it is required that .

Suppose that . We put

If then define

so that . If is a formula in which some names occur, and , then accordingly is the result of substitution of for each name in .

Lemma 10.

Suppose that , in , U is a system in , and is a set -generic over . Then for any set there is a name in such that . If in addition , and , then there is a name in such that .

Proof.

It follows from general forcing theory that there is a name , not necessarily an -size name, such that . Let for all . Arguing in , put

where is a maximal antichain for any x. We observe that in for all x by Lemma 8, hence . And on the other hand, we have .

To prove the additional claim, note that by the product forcing theorem if then the original name can be chosen in , and repeat the argument. □

3.5. Names for Reals in Product Extensions

Now we introduce names for reals (elements of ) in generic extensions of considered. This is an important particular case of the content of Section 3.4.

Assume that in , , e.g., , where U is a system. By (-names for reals in )we denote the set of all such that the sets satisfy the following requirement:

We let , , .

Let (small names) consist of all -size names ; in other words, it is required that for all .

Define the restrictions .

A name is -full iffthe set is pre-dense in K for any . A name is -full below some , iff all sets are pre-dense in K below , i.e., any condition , is compatible with some (and this holds for all ).

Suppose that . A set is minimally -generic iff it is compatible in itself (if then there is with ), and intersects each set . In this case, put

so that and . If is a formula in which some names occur, and a set is minimally -generic for any name in , then accordingly is theresult of substitution of for each name in .

Lemma 11.

Suppose that U is a system in , and is -generic over . Then for any real there is a -full name in such that . If in addition , and , then there is a -full name in such that . □

Proof.

It follows from general forcing theory that there is a -full name , not necessarily an -size name, such that . Then all sets , are pre-dense in . Arguing in , put , where is a maximal antichain for any . We conclude by Lemma 8 that in for all j, hence in fact . And on the other hand, we have . □

Equivalent names. Names are equivalent iff conditions are incompatiblewhenever and for some j and . Names are equivalent below some iff the triple ofconditions is incompatible (that is, no common strengthening) whenever and for some j and .

Lemma 12.

Suppose that in, , and namesare equivalent (resp., equivalent below p). Ifis minimally-generic and minimally-generic (resp., and containing p), then.

Proof.

Suppose that this is not the case. Then by definition there exist numbers j and and conditions and . Then are compatible (as elements of the same generic set), contradiction. □

The next lemma provides a useful transformation of names. Recall that is defined in Section 3.1.

Lemma 13 (in ).

If and , then

is still a name in , equivalent to τ below p, and .

If U is a system and , , then .

Moreover, if τ is -full below p then is -full below p, too.

Proof.

Routine. □

3.6. Permutations

We continue to argue in . There are three important families of transformations of the whole system of objects related to product forcing, considered in this Subsection and the two following ones.

We begin with permutations, the first family. Let be the set of all bijections , i.e., permutations of the set ,such that the set (the essential domain) satisfies . Please note that is the identity outside of . Any permutation acts onto:

- –

- sets : by ;

- –

- systems U: by for all —then ;

- –

- conditions : if then and , and if then , so ;

- –

- sets : by —then ;

- –

- names : by

Lemma 14 (routine).

If then is an order-preserving bijection of onto , and if U is a system then . □

3.7. Multi-Lipschitz Transformations

Still arguing in , we let be the -product of the group (see Section 2.3), this will be our second family of transformations, called multi-Lipschitz. Thus, a typical element is , where has -size, . Define the action of any on:

- –

- systems U: , and for all elements , but for all ;

- –

- conditions : , if then , if then , but if , then ;

- –

- sets : ;

- –

- names : ;

In the first two items, we refer to the action of on sets and on forcing conditions, as defined in Section 2.3.

Lemma 15 (routine).

If then is an order-preserving bijection of onto , and if U is a system then . □

Lemma 16.

Suppose that are systems, , , , and sets , are i-similar for all . Then there is such that , , and for all .

Proof.

Apply Lemma 5 componentwise for every . □

3.8. Multi-Substitutions

Assume that conditions satisfy the following:

In particular, (4) of Section 2.4 holds for all . We define a transformation acting as follows. First, we let , the domain of , contain all conditions such that

- (a)

- if and , then or ;

- (b)

- if and , then or , thus, in other words, in the sense of Section 2.4.

Please note that all conditions and all belong to . On the other hand, if satisfies and (a), then r belongs to as well. In particular, .

If , then define so that and:

- (a1)

- if and then simply ,

- (a2)

- if and , then by (a) either or , where —we put in the first case, and in the second case;

- (b1)

- if either , or , then put ,

- (b2)

- if and , then we put , where is defined in Section 2.4.

Transformations of the form will be called multi-substitutions.

Lemma 17 (in L).

Proof.

Apply Lemma 6 componentwise. □

Corollary 1 (of Lemma 17).

If U is a system thenishomogeneousin the following sense: if then there exist stronger conditions and in , such that the according lower cones and are order-isomorphic. □

Action ofon names. Assume that conditions satisfy (6). Let contain all names such that . If then put

Then obviously .

4. The Basic Forcing Notion and the Model

In this paper, we let be minus the Power Set axiom, with the schema of Collection instead of Replacement, with AC is assumed in the form of well-orderability of every set, and with the axiom: “ exists”. See [8] on versions of sans the Power Set axiom in detail.

Let be plus the axioms: , and the axiom “every set x satisfies ”.

4.1. Jensen—Solovay Sequences

Arguing in , let be systems. Suppose that M is any transitive model of . Define iff and the following holds:

- (a)

- the set is multiply -generic over M,in the sense that every sequence of pairwise different functions is generic over M in the sense of as the forcing notion in , and

- (b)

- if then is dense in , therefore uncountable.

Let , Jensen—Solovay pairs, be the set of all pairs of:

- −

- a transitive model , and a system U,

- −

- such that the sets and U belong to M—then sets also belong to M.

Let , small Jensen—Solovay pairs, be the set of all pairs such that both U and M have cardinality . We define:

- ( extends ) iff and ;

- (strict extension) iff and .

Lemma 18 (in L).

If and , , then there is a pair , such that and .

Proof.

Let . By definition is -closed as a forcing: any -increasing sequence of has the least upper bound in , equal to the union of all . It follows that the countable-support product is -closed, too. Therefore, as , there exists a system , -generic over M. Now define for each (assuming that in case ), and let be any transitive model of cardinality , satisfying and containing . □

Lemma 19 (in ).

Suppose that pairs belong to . Then . Thus ≼ is a partial order on .

Proof.

We claim that is multiply -generic over M. Suppose, for the sake of brevity, that , where —then , , and . (The general case does not differ much.) By definition, f is Cohen generic over M and g is Cohen generic over . Therefore, g is Cohen generic over , because (as ). It remains to apply the product forcing theorem. □

Now, still in , a Jensen—Solovay sequence of length is any strictly -increasing -sequence of pairs , satisfying on limit steps. Let be the set of all such sequences.

Lemma 20 (in ).

Let λ be a limit ordinal, and. Put. Then

- (i)

- for every ξ.

- (ii)

- If moreover and is a transitive model containing then and .

- (iii)

- The same is true in case , but then the model M is not necessarily a -size model, and we require rather than , of course.

Proof.

The same arguments work as in the proof of Lemma 19. □

4.2. Stability of Dense Sets

If U is a system, D is a pre-dense subset of , and is another system extending U, then in principle D does not necessarily remain maximal in , a bigger set. This is where the genericity requirement (a) in Section 4.1 plays its role to seal the pre-density of sets in M w. r. t. further extensions. This is the content of the following key theorem. Moreover, the product forcing arguments will allow us to extend the stability result in pre-dense sets not necessarily in M, as in items (ii), (iii) of the theorem.

Theorem 2 (stability of dense sets).

Assume that, in , , is a system, and . If D is a pre-dense subset of (resp., pre-dense below some ) then D remains pre-dense in (resp., pre-dense below p) in each of the following three cases:

- (i)

- (ii)

- , where is -generic over , and is a PO set;

- (iii)

- , where is finite, is fixed, and .

Proof.

Arguing in , we consider only the case of sets D pre-dense in itself; the case of pre-density below some is treated similarly.

(i) Suppose, towards the contrary, that a condition is incompatible with each . As , we can w.l.o.g. assume that .

We are going to define a condition , also incompatible with each , contrary to the pre-density. To maintain the construction, consider the finite sequence of all elements occurring in but not in U. It follows from that is -generic over M. Moreover, p being incompatible with D is implied by the fact that meets a certain family of dense sets in , of cardinality in M. Therefore, we will be able to simulate this in M, getting a sequence which meets the same dense sets, and hence yields a condition , also incompatible with each .

To present the key idea in sufficient detail in a rather simplified subcase, we assume that

Then , where and are finite sets. The (finite) set is multiply -generic over M since . To make the argument even more transparent, we suppose that

(The general case follows the same idea and can be found in [4]; we leave it to the reader.)

Thus, , where is by definition a finite set.

The plan is to replace the functions by some functions so that the incompatibility of p with conditions in D will be preserved.

It holds by the choice of p and Lemma 1 that , where

and depends on via The equality can be rewritten as , where . Furthermore, is equivalent to

and each is finite. Recall that , therefore , where and . Thus, (9) is equivalent to

Please note that each is a finite subset of , so we can re-enumerate in M and rewrite (10) as follows:

As the pair is -generic, there is an index such that (11) is forced over M by , where and . In other words, holds for all whenever is -generic over M and , . It follows that for any and sequences extending resp. there are sequences extending resp. , at least one of which extends one of sequences . This allows us to define, in M, a pair of sequences , such that , , and for any at least one of extends one of . In other words, we have

It follows that the condition defined by , , , still satisfies (compare with (9)), and further , thus is incompatible with each . Yet since , which contradicts the pre-density of D.

(ii)The above proof works with instead of M since the set X as in the proof is multiple -generic over by the product forcing theorem.

(iii) Assuming w.l.o.g. that , we conclude that is a -generic extension of M. Now, if , then, following the above argument, let . By the definition of ≼ the set is multiply -generic not only over M but also over . This allows the carrying out of the same argument as above. □

Corollary 2.

Under the assumptions of Theorem 2, if a set is -generic over a transitive model containing M and (including the case ), then the intersection is -generic over M.

Proof.

If a set , , is pre-dense in , then it is pre-dense in by Theorem 2, and hence by the genericity. □

Corollary 3 (in ).

Under the assumptions of Theorem 2, if is a -full name then τ remains -full, and if and τ is -full below p, then τ remains -full below p.□

4.3. Complete Sequences and the Basic Forcing Notion

In , we say that a pair solves a set iff either or there is no pair that extends . Let be the set of all pairs whichsolve a given set . A sequence is called -complete () iff it intersects every set of the form , where is a set.

Recall that is the collection of all sets x whose transitive closure has cardinality . Furthermore, means definability by a formula of the -language, in which any definability parameters in are allowed, while means parameter-free definability. Similarly, in the next theorem means that is allowed as a sole parameter. It is a simple exercise that sets and are under .

Generally, we refer to e.g., ([9] (Part B, 5.4)), or ([10] (Chapter 13)) on the Lévy hierarchy of ∈-formulas and definability classes , , for any transitive set H.

Theorem 3 (in ).

Let . There is a sequence of class , hence, in case , -complete in case , and such that for all .

Proof.

To account for as a parameter, note that the set is , and hence the singleton is . Indeed “being ” is equivalent to the conjunction of “being uncountable”—which is , and “every smaller ordinal is countable”—which is since the quantifier “for all smaller ordinals” is bounded, hence, it does not increase the complexity.

It follows that in case , supporting the “hence” claim of the theorem.

Then, it can be verified that the sets are . (Indeed “being finite” and “being countable” are relations, while “being of cardinality ” is ; the definition says that there is no injection from into a given set.)

Define pairs , by induction. Let be the null system with , and be the least CTM of . If is a limit, then put and let be the least CTM of containing the sequence . If is defined, then by Lemma 18 there is a pair with and . Further let be a universal set, and if then . Let be the -least pair satisfying , where isthe Gödel wellordering of , the constructible universe. This completes the inductive construction of , .

To check the definability property, make use of the well-known fact that the restriction is a relation, and if , is any parameter, and is a finitary relation on then the relations and (with arguments ) are as well. □

Definition 2 (in ).

Fix a numberduring the proof of Theorem 1.

- Let be any -complete Jensen–Solovay sequenceof class as in Theorem 3—in case , or just any Jensen–Solovay sequence of class —in case , as in Theorem 3, including for all ξ in both cases.

- Put , so for all . Thus, is a system and since for all ξ.

We define (the basic forcing notion), and for . Thus, is the finite-support product of the set and sets ; so that . □

Corollary 4.

Suppose that in , and M is a TM of containing the sequence . Then

- (i)

- , , and if then in .

- (ii)

- If is a set -generic over then the set is -generic over .

Proof.

Make use of Lemma 20 and Corollary 2 in Section 4.2. □

Lemma 21 (in ).

The binary relation , the sets and (-names for reals in ), and the set of all -full names in are , and even in case .

Proof.

The sequence is by definition, hence the relation is . On the other hand, if belongs to some then obviously implies , leading to a definition of the relation . To prove the last claim, note that by Corollary 3 if a name is -full then it remains -full. □

4.4. Basic Generic Extension

The proof of Theorem 1 makes use of a generic extension of the form , where is a set -generic over , and . The following two theorems will play the key role in the proof. Define formulas () as follows:

Lemma 22.

Suppose that a set is -generic over , and , . Then

- (i)

- ,

- (ii)

- if then , and if then ,

- (iii)

- holds,

- (iv)

- , and generally, there are no sets in satisfying .

Proof.

To prove (i) apply Lemma 9 (ii) (ii); is easy. Furthermore, Lemma 9 (vi) immediately implies (iii).

To prove (iv), we need more work. Let . Suppose towards the contrary that some satisfies . It follows from Lemma 10 (with and ), that there is a name in such that . There is an ordinal satisfying and . Then , where is -generic over by Corollary 4 (ii), and by the way S belongs to by the choice of .

Please note that by Corollary 4 (i). Let . Then f is Cohen generic over the model by Corollary 4. On the other hand, is -generic over by Theorem 2 (iii). Therefore f is Cohen generic over as well.

Recall that and holds, hence S does not cover f. As f is Cohen generic over , it follows that there is a sequence , such that S contains no subsequences of f extending s. Take any . By Corollary 4 (i), there exists a function , satisfying . Then, S covers g by . However, this is absurd by the choice of s. □

The proof of the next important elementary equivalence theorem will be given below in Section 6.3.

Theorem 4 (elementary equivalence theorem).

Assume that in , , sets satisfy and , the symmetric difference is at most countable, and the complementary set is infinite.

Let be -generic over , and be any real. Then any closed formula φ, with real parameters in , is simultaneously true in and in .

4.5. The Main Theorem Modulo the Elementary Equivalence Theorem: The Model

Here we begin the proof of Theorem 1 on the base of Theorem 4 of Section 4.4. We fix a number during the proof. The goal is to define a generic extension of in which for any set the following is true: iff . The model is a part of the basic generic extension defined in Section 4.4.

In the notation of Definition 2 in Section 4.3, consider a set , -generic over . Then is a -generic map from onto by Lemma 9 (i). We define

and . We also define, for any ,

and accordingly and .

With these definitions, each kth slice

of is necessarily infinite and coinfinite, and it codes the target set since

It will be important below that definition (12) is monotone w. r. t. , i.e., if for all k, then and . Non-monotone modifications, like e.g.,

would not work. Finally, let

Anyway, (the ordinal product) is a set in the model for each m, containing , while for all m. We are going to prove the following lemma:

Lemma 23.

The model witnesses Theorem 1. That is, let a set be -generic over . Then it holds in that

- (i)

- is and each set is

- (ii)

- if is then .

Recall that if then .

Proof (Claim (i) of the lemma).

Consider an arbitrary ordinal ; . We claim that

holds in . Indeed, assume that . Then , and we have in by Lemma 22 (ii), (iii). Conversely assume that . Then we have , but contains no S with by Lemma 22 (iv).

However, the right-hand side of (15) defines a relation in by Lemma 21. (Indeed, in , therefore is in .) On the other hand, the sets and remain singletons in , so they can be eliminated since . This yields in . It follows that by ([10] (Lemma 25.25)), as required.

Consider an arbitrary set . By genericity there exists such that . Then by (12), therefore x is as well. However, by the same argument. Thus, x is in , as required. (Claim (i) of Lemma 23) □

4.6. Proof of the Key Claim of Lemma 23

The proof of Lemma 23 (ii) is based on several intermediate lemmas.

Recall that .

Lemma 24

(compare with Lemma 33 in [7]). Suppose that is -generic over , and . Let be any set in . Then any closed formula Φ, with reals in as parameters, is simultaneously true in and in .

It follows that if in , then any closed formula Ψ, with parameters in , true in , is true in as well.

Proof (Lemma 24)).

There is an ordinal such that all parameters in belong to , where and . The set Y belongs to , in fact, . Therefore is equi-constructible with the pair , where is a map from onto, essentially, . It follows that there is a real with . Then all parameters of belong to .

To prepare for Theorem 4 of Section 4.4, put , , ,

As , we have , and hence . It follows by Theorem 4 that is simultaneously true in and in . However, by construction, while , and we are done. □

In continuation of the proof of Lemma 23 (ii), suppose that

- (†)

- and are parameter-free formulas that provide a definition for a set , i.e., we havein . Thus, the equivalence is forced to be true in by a condition .

Here, is the canonical -name for the generic set , as usual, while is a name for .

Lemma 25.

Assume (†). If then the sentence “” is -decided by .

Proof.

Suppose, for the sake of simplicity, that is the empty condition ⊙ (i.e., ); the general case does not differ much. Then holds in for any generic set .

Say that conditions are close neighbours iff and one of the following holds:

- (I)

- (recall that ), or

- (II)

- , , and either (a) for all , or (b) for all .

Proposition 1.

If conditions are close neighbours, satisfying (6) in Section 3.8, , and p -forces the sentence“”, then so does q.

Proof (Proposition).

Suppose on the contrary that q does not force “”. As satisfy (6), the associated transformation maps the set onto order-preserving by Lemma 17 (with ). By the choice of q, there is a set , generic over , containing q, and such that is false in . Then is true in by (†) (and the assumption that ).

The set is -generic over as well (as is an order isomorphism), and contains p, and hence is true and false in .

Case 1: (I) holds, i.e., . Then by definition , so that . On the other hand, the sets and are equi-constructible by means of the application of , and hence and are equi-constructible, that is, the classes and coincide. However, is true in one of them and false in the other one, a contradiction.

Case 2: (II) holds. Let . Then for all via . This implies , and also implies , while the difference between the sets , is that for any and any j,

Moreover, (II) implies , and hence for all via . We conclude that for any set , in particular, .

If now (II) (a) holds, then by (16), where

However, holds in , see above. It follows by Lemma 24 that holds in . However, we know that . Thus, holds in , which is a contradiction to the above. If (II) (b) holds, then argue similarly using the formula . (Proposition 1) □

Coming back to Lemma 25, suppose towards the contrary that “” is not -decided by . There are two conditions such that p -forces “” while q-forces the negation. We may w.l.o.g. assume, by Lemma 17 (i), that satisfy (6) of Section 3.8. We claim that p, q can be connected by a finite chain of conditions in in which each two consecutive terms are close neighbours in the sense above, satisfying (6) in Section 3.8— then Proposition 1 implies a contradiction and concludes the proof of Lemma 25.

Thus, it remains to prove the connection claim. Let be defined by and . Then are close neighbours and (6) holds for this pair as it holds for . Let be defined by for all and . Still r is a close neighbour to both and q, and (6) holds for and . Thus, the chain p——r—q proves the connection claim. (Lemma 25) □

Now, to accomplish the proof of Lemma 23 (ii), apply Lemma 25.

(Lemma 23) □

(Theorem 1 modulo Theorem 4 of Section 4.4) □

5. Forcing Approximation

To prove Theorem 4 of Section 4.4 and thus complete the proof of Theorem 1 in the next Section 6, we define here a forcing-like relation forc, and exploit certain symmetries of objects related to forc. This similarity will allow us to only outline really analogous issues but concentrate on several things which bear some difference.

We argue under Blanket Assumption 1.

Recall that is minus the Power Set axiom, with the schema of Collection instead of Replacement, with the axiom “ exists”, and with AC in the form of wellorderability of every set, and is plus the axioms: , and “every set x satisfies ”.

5.1. Formulas

Here we introduce a language that will help us to study analytic definability in -generic extensions, for different systems U, and their submodels.

Let be the 2nd order Peano language, with variables of type 1 over . If then an formula is any formula of , with somefree variables of types replaced by resp. numbers in and names in , and some type 1 quantifiers are allowed to have bounding indices B (i.e., ) such that satisfies either or (in ). In particular, itself can serve as an index, and the absence

If is a formula, then let

If a set is minimally -generic(that is, minimally -generic w. r. t. every name , in the sense of Section 3.5), then the valuation is the result of substitution of for any name , and changing each quantifier , to resp. , while index-free type 1 quantifiers are relativized to ; is a formula of with real parameters, and some quantifiers of type 1 relativized to certain submodels of .

An arithmetic formula in is a formula with no quantifiers of type 1 (names in are allowed). If then let a , resp., formulabe a formula of the form

respectively, where is an arithmetic formula in , all variables are of type 1 (over ), the sign means that this quantifier can have a bounding index as above, and it is required that the rightmost (closest to the kernel ) quantifier does not have a bounding index.

If in addition is a transitive model and then define

all formulas such that and each index satisfies the requirement: either or .

Define similarly.

5.2. Forcing Approximation

We introduce a convenient forcing-type relation for pairs in and formulas in , associated with the truth in -generic extensions of , where and is a system.

- (F1)

- First, writing , it is assumed that:

- (a)

- and p belongs to ,

- (b)

- is a closed formula in for some , and each name is -full below p.

Under these assumptions, the sets belong to M.

The definition of forc goes on by induction on the complexity of formulas.

- (F2)

- If , and is a closed formula in (then by definition it has no quantifier indices), then: iff (F1) holds and p-forces over M in the usual sense. Please note that the forcing notion belongs to M in this case by (F1).

- (F3)

- If , then:

- (a)

- iff there is a name , -full below p (by (F1)b) and such that .

- (b)

- iff there is a name , -full below p (by F1)b) and such that .

- (F4)

- If , is a closed formula, , and (F1) holds, then iff we have for every pair extending , and every condition , where is the result of canonical conversion of to .

The next theorem classifies the complexity of forc in terms of projective hierarchy. Please note that if and then any formula in belongs to M if we somehow “label” any large index (such that ) by its small complement . Therefore, the sets

and similarly defined, are subsets of (in ).

Lemma 26 (in L).

The sets and belong to .

If then the sets and belong to .

Proof

(sketch) Suppose that is . Under the assumptions of the theorem, items (F1)a, (F1)b of (F1) are relations, while (F2) is reducible to a forcing relation over M that we can relativize to M. The inductive step goes on straightforwardly using (F3), (F4). Please note that the quantifier over names in (F3) is a bounded quantifier (bounded by M), hence it does not add any extra complexity. □

5.3. Further Properties of Forcing Approximations

The notion of names being equivalent below some ,is introduced in Section 3.5. We continue with a couple of routine lemmas.

Lemma 27.

Suppose that satisfy (F1) of Section 5.2, and . Let be another list of names in , -full below p, and such that and are equivalent below p for each . Then iff .

Proof.

Suppose that is . Let be a set -generic over M, and containing p. Then for all ℓ by Lemma 12. This implies the result required, by (F2) of Section 5.2.

The induction steps and are carried out by an easy reduction to items (F3), (F4) of Section 5.2. □

Lemma 28 (in ).

Let satisfy (F1) of Section 5.2. Then:

- (i)

- if , φ is , and , then fails;

- (ii)

- if , , and , then

Proof.

Claim (i) immediately follows from (F4) of Section 5.2.

To prove (ii) let be a closed formula in , where all -names belong to M and are -full below p. Then all names remain -full below p by Corollary 3 in Section 4.2, therefore below q as well since . Consider a set , -generic over and containing q. We have to prove that is true in . Please note that the set is -generic over M by Corollary 2 in Section 4.2, and we have . Moreover, the valuation coincides with since all names in belong to . And is true in as . It remains to apply Mostowski’s absoluteness (see [10] (p. 484) or [11]) between the models .

The induction steps related to (F3), (F4) of Section 5.2 are easy. □

5.4. Transformations and Invariance

To prove Theorem 4 of Section 4.4, we make use of the transformations considered in Section 3.6, Section 3.7 and Section 3.8. In addition to the definitions given there, define, in , the action of any transformation (permutation), (multi-Lipschitz), or one of the form (multisubstitution), on -formulas with quantifier indices and names in as parameters.

- (I)

- Assume that . To get replace each quantifier index B (in or ) by and each name by .

- (II)

- Assume that . To get replace each name in by , but do not change quantifier indices.

- (III)

- Assume that satisfy (6) of Section 3.8, and all names occurring in belong to . To get replace each name in by , but do not change quantifier indices.

Lemma 29 (in L).

Suppose that , , , φ is a formula in , and is coded in M in the sense that and . Then: iff . □

Proof.

Under the conditions of the lemma, acts as an isomorphism on all relevant domains and preserves all relevant relations between the objects involved. Thus, still satisfy (F1) in Section 5.2. This allows proof of the lemma by induction on the complexity of .

Base. Suppose that is a closed formula in . Then is a closed formula in . Moreover, the map is an order isomorphism (in M) by Lemma 14. We conclude that a set is -generic over M iff is, accordingly, -generic over M, and the valuated formulas and coincide. Now the result for formulas follows from in Section 5.2.

Step. Let be a formula, and be . Assume . By definition there is a name , -full below the given , such that . Then, by the inductive hypothesis, we have , and hence by definition .

The case of being is similar.

Step. This is somewhat less trivial. Assume that is a closed formula; all names in belong to and are -full below p. Then is a closed formula, whose all names belong to and are -full below . Suppose that fails.

By definition there exist a pair with , and a condition , such that . Then by the inductive hypothesis. Yet the pair belongs to and extends . (Recall that and is coded in M.) In addition, , and . Therefore, the statement fails, as required. □

Lemma 30 (in L).

Suppose that , , φ is a formula in , and . Then: iff .

Proof.

Similar to the previous one, but with a reference to Lemma 15 rather than Lemma 14. □

Lemma 31 (in L).

Assume that , conditions satisfy (6) of Section 3.8, , φ is a closed formula in with all names in (see Section 3.8), and . Then: iff .

Proof.

Similar to the proof of Lemma 29, except for the step , , where we need to take additional care to keep the names involved in . Thus, let be a formula, with names in , and let be . Assume that .

By definition there is a name , -full below r, such that . Please note that does not necessarily belong to . However, the restricted name (see Lemma 13 in Section 3.8) is still a name in because , and we have , so that . Moreover, is equivalent to below r by Lemma 13. We conclude that , by Lemma 27.

Then, by the inductive hypothesis, we have , and hence by definition via . □

6. Elementary Equivalence Theorem

The goal of this section is to prove Theorem 4 of Section 4.4, and accomplish the proof of Theorem 1. We make use of the relation forc defined above, and exploit certain symmetries in forc studied in Section 5.4.

6.1. Hidden Invariance

To explain the idea, one may note first that elementary equivalence of subextensions of a given generic extension is usually a corollary of the fact that the forcing notion considered is enough homogeneous, or in different words, invariant w. r. t. a sufficiently large system of order-preserving transformations. The forcing notion we consider, as well as basically any , is invariant w. r. t. multi-substitutions by Lemma 17. However, for a straightaway proof of Theorem 4 we would naturally need the invariance under permutations of Section 3.6—to interchange the domains Z and , whereas is definitely not invariant w. r. t. permutations.

On the other hand, the relation is invariant w. r. t. both permutations (Lemma 29) and multi-Lipschitz (Lemma 30), as well as still w. r. t. multi-substitutions by Lemma 31. To bridge the gap between (not explicitly connected with in any way) and -generic extensions, we prove Lemma 33, which ensures that admits a forcing-style association with the truth in -generic extensions, bounded to formulas of type and below. This key result will be based on the -completeness property (Definition 2 in Section 4.3). Speaking loosely, one may say that some transformations, i.e., permutations and multi-Lipschitz, are hidden in construction of , so that they do not act per se, but their influence up to th level, is preserved.

This method of hidden invariance, i.e., invariance properties (of an auxiliary forcing-type relationship like ) hidden in by a suitable generic-style construction of , was introduced in Harrington’s notes [3] in a somewhat different terminology. We may note that the hidden invariance technique is well known in some other fields of mathematics, including more applied fields, see e.g., [12,13].

6.2. Approximations of the -Complete Forcing Notion

We return to the forcing notion defined in as in Definition 2 in Section 4.3 for a given number of Theorem 1. Arguing in , we let the pairs , also be as in Definition 2. Let denote the relation , and let mean: .

Claims (i), (ii) of Lemma 28 take the form:

- (I)

- and () contradict to each other.

- (II)

- If and , , then .

The next lemma shows that satisfies a key property of forcing relations up to the level of formulas.

Lemma 32.

If φ is a closed formula in , , and all names in φ are -full below p, then there is a condition , such that either , or .

Proof.

As the names considered are -size objects, there is an ordinal such that , and all names in belong to ; then all names in are -full below p, of course. As , the set D of all pairs that extend and there is a condition , satisfying , belongs to by Lemma 26. Therefore, by the -completeness of the sequence , there is an ordinal , such that .

We have two cases.

Case 1: . Then there is a condition , satisfying , that is, . However, obviously .

Case 2: there is no pair extending . Prove . Suppose otherwise. Then by the choice of and (F4) in Section 5.2, there exist: a pair extending , and a condition , such that . Then , a contradiction. □

Now we prove another key lemma which connects, in a forcing-style way, the relation and the truth in -generic extensions of , up to the level of formulas.

Lemma 33.

Suppose that φ is a formula in , and all names in φ are -full. Let be -generic over . Then is true in iff there is a condition such that .

Proof.

We proceed by induction and begin with the case of formulas. Consider a closed formula in . As names in the formulas considered are -size names in , there is an ordinal such that is a formula. Please note that since is -generic over , the smaller set is -generic over by Corollary 2 in Section 4.2, and the formulas , coincide by the choice of . Therefore

iff holds in :

iff holds in by the Mostowski absoluteness [10] (p. 484),

iff there is which -forces over ,

iff by (F2) in Section 5.2,

easily getting the result required since is arbitrary.

The step from to , . Prove the theorem for a formula , assuming that the result holds for . Suppose that is false in . Then is true, and hence by the inductive hypothesis, there is a condition such that . Then it follows from (I) and (II) above that fails for all .

Conversely let fail for all . Then by Lemma 32 there exists satisfying . It follows that is true by the inductive hypothesis, therefore is false.

The step from to . Let be a formula; prove the result for a formula . If and then by definition there is a name , -full below p, and such that . Then holds by the inductive hypothesis, and this implies since obviously .

If conversely is true, then by Lemma 11 there is a -full name such that is true. Then, by the inductive hypothesis, there is a condition such that . Therefore by the choice of .

The case of is treated similarly. □

6.3. The Elementary Equivalence Theorem

We begin the proof of Theorem 4 of Section 4.4, so let be as in the theorem.

Step 1. We assume w.l.o.g. that itself is the only parameter in the formula of Theorem 4. By Lemma 11, there exists, in , a -full name such that and . Thus, is , where is a parameter-free formula with a single free variable. Then .

We also assume w.l.o.g. that the sets satisfy the requirement that and are infinite (countable) sets. Indeed, otherwise, under the assumptions of Theorem 4, one easily defines a third set such that each of the pairs and still satisfies the assumptions of the theorem, and in addition, all four sets , , and are infinite. Please note that this argument necessarily requires that the complementary set is infinite.

Step 2. We are going to reorganize the quantifier prefix of , in particular, by assigning the indices Z and to certain quantifiers, to reflect the relativization to classes and . This is not an easy task because generally speaking there is no set in satisfying . However, nevertheless we will define an formula, say , and then by the substitution of for Z, such that the following will hold:

- (A)

- For any set , -generic over

(See Section 5.1 on the interpretation for any -formula .)

To explain this transformation, assume that for the sake of brevity, and hence has the form , where is a formula. To begin with, we define

and define accordingly.

Lemma 34.

The formulas , satisfy (A).

Proof.

To prove the implication , suppose that holds in , so that there is a real satisfying in . By a standard argument there is a real with . We claim that these reals and witness that holds in , that is, we have in .

Indeed, suppose that and . Then , of course. Therefore is true in by the choice of . We conclude that is true in as well by the Shoenfield absoluteness theorem, as is a formula.

The inverse implication is proved similarly. (Lemma) □

Thus, the formulas , do satisfy (A), but they are not formulas as defined in Section 5.1, of course. It will take some effort to convert them to a form. We must recall some instrumentarium known in Gödel’s theory of constructability of reals.

- If then define reals and in by and for all k. If then define such that , .

- There is a set of codes of countable ordinals, defined by a formula , so that is the ordinal coded by , and , see ([14] (1E))).

As a one more pre-requisite, we make use of a system of maps , , such that:

- (a)

- if then , and

- (b)

- there exist a formula and a formula such that if then for all ,

see e.g., ([14] (Theorem 2.6)). Recall that by Lemma 22.

Now consider the formula

and define similarly.

We keep the global understanding that the quantifiers are relativized to .

Lemma 35.

The formulas and are equivalent in , and the same for and

Proof (Lemma).

To prove the implication , assume that holds in , and this is witnessed by reals and satisfying in . Please note that by Lemma 9 (ii). It follows by (a) that there is an ordinal with , and then there is a real with .

Now let , so that , , and . We claim that witnesses in . Indeed, assume that and , , and ; we must prove that is true in .

However, we have by construction, where by the choice of . Now it follows by the choice of that indeed holds, as required.

The proof of the inverse implication is similar. (Lemma) □

Please note that the formula can be converted to the following logically equivalent form:

And here the kernel can be converted to a true form, say , with the help of the formulas S and P of (b), and because is and is . This yields a formula , equivalent to , and hence satisfying (A) by Lemmas 34 and 35, as required.

Step 3. Assuming that the formula is true in , the transformed formula holds in by (A). By Lemma 33 there is a condition such that that is, there is an ordinal such that —then by definition . We w.l.o.g. assume that p and satisfy the following two requirements:

- (B)

- (recall that , are infinite, Step 1).

- (C)

- , and if then and the sets and are i-similar (see Section 2.3).

Please note that if then still by Lemma 28. Therefore, we can increase below so that the following holds:

- (D)

- the sets d, , belong to and are subsets of .

Step 4. Now, to finalize the proof of Theorem 4, it suffices (by Lemma 33) to prove:

Lemma 36.

We have as well.

Proof (Lemma).

Let ; then by (D), and . There is a bijection , , such that

- (E)

- is the identity, f maps onto and vice versa.

Then, by (B), f maps onto . Let be the trivial extension of f onto : for . Thus, is coded in in the sense of Lemma 29, and . We have by the choice of , hence and . Moreover, because and is the identity by (E). It follows that by Lemma 29, where , . Please note that , , , , . Also note that

- (F)

- if then the sets , are i-similar by (C), (E).

We conclude, by Lemma 16, that there is a transformation , such that , the identity for all , and for all , where . Then we have by Lemma 30. Here by the choice of , because . And holds by the same reason.

It remains to derive from . Please note that satisfy (6) of Section 3.8 by construction, hence the transformation is defined. Moreover, the only name occurring in satisfies , and is the identity by (E). It follows that , and . We conclude that Lemma 31 is applicable. This yields , as required. (Lemma 36) □

(Theorem 4 of Section 4.4) □

(Theorem 1, see Section 4.5) □

7. Conclusions and Discussion

In this study, the method of almost-disjoint forcing was employed to the problem of getting a model of in which the constructible reals are precisely the reals, for different values . The problem appeared under no 87 in Harvey Friedman’s treatise One hundred and two problems in mathematical logic [1], and was generally known in the early years of forcing, see, e.g., problems 3110, 3111, 3112 in an early survey [2] by A. Mathias. The problem was solved by Leo Harrington, as mentioned in [1,2] and a sketch of the proof mainly related to the case in Harrington’s own handwritten notes [3].

From this study, it is concluded that the hidden invariance technique (as outlined in Section 6.1) allows the solution of the general case of the problem (an arbitrary ), by providing a generic extension of in which the constructible reals are precisely the reals, for a chosen value , as sketched by Harrington. The hidden invariance technique has been applied in recent papers [7,15,16,17] for the problem of getting a set theoretic structure of this or another kind at a pre-selected projective level. We may note here that the hidden invariance technique, as a true mathematical technique, also has multiple applications both in the physical and engineering fields. In this regard, we cite works [18,19] that have exploited this technique (albeit simplified) for engineering applications.

We continue with a brief discussion with a few possible future research lines.

1. Harvey Friedman completes [1] with a modified version of the above problem, defined as Problem 87: find a model of

This problem was also known in the early years of forcing, see, e.g., problem 3111 in [2]. Problem (20) was solved in the positive by René David [20], where the question is attributed to Harrington. So far it is unknown whether this result generalizes to higher classes , , or , and whether it can be strengthened towards instead of . This is a very interesting and perhaps difficult question.

2. Another question to be mentioned here is the following. Please note that in any extension of satisfying Theorem 1, it is true that every universal set is by necessity but non-, and hence nonconstructible. This gives another proof of Theorem 3 in [7]. (It claims, for any , the existence of a generic extension of in which there is a nonconstructible set whereas all sets are constructible.) And the problem is, given , to find a model in which

all reals are constructible, but there exists a nonconstructible real , which satisfies .

Neither the model considered in Section 4.5 above, nor the model for ([7] (Theorem 3)), suffice to solve the problem, because these models in principle are incompatible with for a real u.

3. For any , let be the set of all reals (here subsets of ), definable by a type-theoretic parameter-free formula whose quantifiers have types bounded by n from above. In particular, = arithmetically definable reals and = analytically definable reals. Alfred Tarski asked in [6] whether it is true that for a given , the set belongs to , that is, is itself definable by a type-theoretic parameter-free formula whose quantifiers have types bounded by n. The axiom of constructibility implies that , so the problem is to find a generic model in which holds, and moreso the equality holds. We believe that such a model can be constructed by an appropriate modification of the methods developed in this paper.

4. It will be interesting to apply the hidden invariance technique to some other forcing notions and coding systems (those not of the almost-disjoint type), such as in [21,22].

5. This is a rather technical question. One may want to consider a smaller extension instead of in Lemma 23. Claim (i) of Lemma 23 then holds for such a smaller model in virtue of the same argument as above. However, the proof of Claim (ii) of Lemma 23, as given above for , does not go through for . The obstacle is that if we try to carry out the proof of Lemma 24 for , then it may well happen that say , and then Theorem 4 is not applicable. It is an interesting problem to figure out whether in fact Claim (ii) of Lemma 23 holds in .

Supplementary Materials

Table of contents and Index are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7390/8/9/1477/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.K. and V.L.; methodology, V.K. and V.L.; validation, V.K. and V.L.; formal analysis, V.K. and V.L.; investigation, V.K. and V.L.; writing original draft preparation, V.K.; writing review and editing, V.K.; project administration, V.L.; funding acquisition, V.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Russian Foundation for Basic Research RFBR grant number 18-29-13037.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their thorough review and highly appreciate the comments and suggestions, which significantly contributed to improving the quality of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Friedman, H. One hundred and two problems in mathematical logic. J. Symb. Log. 1975, 40, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, A.R.D. Surrealist landscape with figures (a survey of recent results in set theory). Period. Math. Hung. 1979, 10, 109–175, The original preprint of this paper is known in typescript since 1968 under the title “A survey of recent results in set theory”. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, L. The Constructible Reals Can Be (Almost) Anything. Preprint Dated May 1974 with the Following Addenda Dated up to October 1975: (A) Models Where Separation Principles Fail, May 74; (B) Separation without Reduction, April 75; (C) The Constructible Reals Can Be (Almost) Anything, Part II, May 75. Available online: http://logic-library.berkeley.edu/catalog/detail/2135 (accessed on 25 August 2020).

- Jensen, R.B.; Solovay, R.M. Some applications of almost disjoint sets. In Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics; Bar-Hillel, Y., Ed.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; London, UK, 1970; Volume 59, pp. 84–104. [Google Scholar]

- Hinman, P.G. Recursion-Theoretic Hierarchies; Perspectives in Mathematical Logic; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1978; p. 480. [Google Scholar]

- Tarski, A. A problem concerning the notion of definability. J. Symb. Log. 1948, 13, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. Models of set theory in which nonconstructible reals first appear at a given projective level. Mathematics 2020, 8, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitman, V.; Hamkins, J.D.; Johnstone, T.A. What is the theory ZFC without power set? Math. Log. Q. 2016, 62, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwise, J. (Ed.) Handbook of mathematical logic. In Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977; Volume 90, p. 375. [Google Scholar]

- Jech, T. Set Theory, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2003; p. xiii + 769. [Google Scholar]

- Kanovei, V. An Ulm-type classification theorem for equivalence relations in Solovay model. J. Symb. Log. 1997, 62, 1333–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.G. On Some Questions of Definability in the Third Order Arithmetic and a Generalization of Jensen Minimal Real Theorem; VINITI Deposited Preprint 839/75; VINITI RAS: Moscow, Russia, 1975; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kanovei, V. On the nonemptiness of classes in axiomatic set theory. Math. USSR Izv. 1978, 12, 507–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.G.; Lyubetsky, V.A. On some classical problems in descriptive set theory. Russ. Math. Surv. 2003, 58, 839–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. Definable E0 classes at arbitrary projective levels. Ann. Pure Appl. Log. 2018, 169, 851–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. Definable minimal collapse functions at arbitrary projective levels. J. Symb. Log. 2019, 84, 266–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. Non-uniformizable sets with countable cross-sections on a given level of the projective hierarchy. Fundam. Math. 2019, 245, 175–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angiulli, G.; Jannelli, A.; Morabito, F.C.; Versaci, M. Reconstructing the membrane detection of a 1D electrostatic-driven MEMS device by the shooting method: Convergence analysis and ghost solutions identification. Comput. Appl. Math. 2018, 37, 4484–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Barba, P.; Fattorusso, L.; Versaci, M. Electrostatic field in terms of geometric curvature in membrane MEMS devices. Commun. Appl. Ind. Math. 2017, 8, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, R. reals. Ann. Math. Log. 1982, 23, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.D.; Gitman, V.; Kanovei, V. A model of second-order arithmetic satisfying AC but not DC. J. Math. Log. 2019, 19, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagila, A. The Bristol model: An abyss called a Cohen reals. J. Math. Log. 2018, 18, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).