Abstract

This paper relates two interesting paradigms in fuzzy logic programming from a semantical approach: core fuzzy answer set programming and multi-adjoint normal logic programming. Specifically, it is shown how core fuzzy answer set programs can be translated into multi-adjoint normal logic programs and vice versa, preserving the semantics of the starting program. This translation allows us to combine the expressiveness of multi-adjoint normal logic programming with the compactness and simplicity of the core fuzzy answer set programming language. As a consequence, theoretical properties and results which relate the answer sets to the stable models of the respective logic programming frameworks are obtained. Among others, this study enables the application of the existence theorem of stable models developed for multi-adjoint normal logic programs to ensure the existence of answer sets in core fuzzy answer set programs.

1. Introduction

Multi-adjoint logic programming (MALP) was introduced in [1] in order to generalize different non-classical logic programming approaches [2,3]. A multi-adjoint logic program is characterized by the use of different implications in its rules and general operators in the body of its rules. These features make multi-adjoint logic programming a flexible framework with potential applications. Since its introduction, multi-adjoint logic programming has broadly been studied in order to, for example, improve the computation of the least model with either an efficient unfolding process [4,5] or with the computation of reductants [6,7]; consider propositional symbols of different sorts and termination theorems [8,9]; analyze incoherence and contradiction measures [10,11]; and extend it to a first order logic [12,13]. Later, multi-adjoint normal logic programming (MANLP) was presented as an extension of multi-adjoint logic programming, where the use of a negation operator is allowed in the body of the rules [14]. A complete study on the syntax and semantics of multi-adjoint normal logic programs, containing important results about the existence and the unicity of stable models, was carried out in [14]. Recently, extended multi-adjoint logic programming (EMALP) has been proposed with the purpose of increasing the versatility and the expressive power of the multi-adjoint approach, by means of the inclusion of different negation operators in the body of the rules and the consideration of constraint rules [15]. Besides presenting the syntax and the semantics of extended multi-adjoint logic programs, which is also based on stable models, a procedure to translate extended multi-adjoint logic programs into semantically equivalent multi-adjoint normal logic programs was provided in [15].

Core fuzzy answer set programming (CFASP) was introduced in [16] as a logic programming framework, endowed with a compact simple language, which is capable of accommodating different fuzzy logic programming formalisms proposed in the literature, such as fuzzy logic programming [3], normal residuated logic programming [17], and fuzzy answer set programming [18]. Specifically, this framework provides a bridge between rich and expressive answer set logic languages, and a small core language that is easy to implement and reason about.

This paper is focused on relating multi-adjoint normal logic programs to core fuzzy answer set programs from a semantical perspective. This relation is carried out in both directions, from MANLP to CFASP and from CFASP to MANLP, and it pursues two main objectives. On the one hand, we aim to combine the great expressivity of EMALPs with the simplicity and compactness of CFASPs. In other words, we aspire to handle a flexible powerful language with a significant potential for modelling problems, such as EMALP, and at the same time work in a framework with high computational efficiency, easier to implement and reason about, as CFASP. That ambition is achieved presenting a method which transforms a MANLP into a CFASP such that the stable models of the former coincide with the answer sets of the later, that is, both programs are semantically equivalent. As a result, the task initiated in [15] will be completed, giving rise to a procedure to translate an EMALP into a semantically equivalent CFASP.

On the other hand, this paper also illustrates how results related to the semantics of a logic programming framework can be applied in other logic programming settings concerning its canonical models. In particular, we focus on MANLP and CFASP. For this purpose, a method for translating an arbitrary CFASP into a semantically equivalent MANLP has been shown. Among others, this method entails the possibility of using current theorems in MALP and MANLP in CFASP, such as the existence theorem for stable models given in the multi-adjoint framework [14], to provide a sufficient condition for the existence of answer sets.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 includes preliminary notions associated with the logic programming frameworks considered in this study, multi-adjoint normal logic programming and core fuzzy answer set programming. Section 3 presents a procedure to translate multi-adjoint normal logic programs into semantically equivalent core fuzzy answer set programs. Section 4 carries out a reciprocal study to the one given in the previous section, that is, a method to translate core fuzzy answer set programs into semantically equivalent multi-adjoint normal logic programs is shown. Technical properties and results relating stable models to answer sets of the corresponding logic programming frameworks are proven. Section 5 provides some conclusions and prospects for future work.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we recall the syntax and the semantics of the two logic programming settings involved in this manuscript: multi-adjoint normal logic programming and core fuzzy answer set programming. We assume that the reader is familiar with the basic notions of lattice theory.

2.1. Multi-Adjoint Normal Logic Programming

Multi-adjoint normal logic programming was presented in [14] as a general non-monotonic logic programming framework, which is characterized by the use of different adjoint pairs and a negation operator. Its syntax is defined from a multi-adjoint lattice with negation.

Definition 1.

The tuple is a multi-adjoint lattice with negation if the following properties are verified:

- 1.

- is a complete lattice, with a bottom and a top .

- 2.

- is an adjoint pair in , for each . That is, is order-preserving in both arguments, is order-preserving in the first argument and order-reserving in the second argument, andfor all .

- 3.

- The boundary conditions with respect to the top element. Specifically, , for all and .

- 4.

- is a negation operator, that is, an order-reversing mapping satisfying and .

Example 1.

The most usual adjoint pairs are those formed by the Gödel, product and Łukasiewicz t-norms together with their residuated implications, defined as follows, for all :

Remark 1.

A notable consequence of the adjoint property and the boundary condition with the top element in the first argument (, for all ) is the equivalence between and .

A multi-adjoint normal logic program is composed of a set of weighted rules where different implications may appear.

Definition 2.

Let be a multi-adjoint lattice with negation. A multi-adjoint normal logic program (MANLP) is a finite set of weighted rules of the form:

where , @ is an aggregator operator (note that the notion of aggregator operator considered in [14] is just an order-preserving mapping), ϑ is an element of L and are propositional symbols such that , for all with . The propositional symbol p is called head of the rule, is called body of the rule and the value ϑ is its weight. The set of propositional symbols appearing in is denoted as .

The following example presents a particular multi-adjoint normal logic program, which will be used for introducing the different notions recalled in this section.

Example 2.

Let be the multi-adjoint lattice with the standard negation, defined as , for each . The following rules form a MANLP:

Similarly to normal residuated logic programs [17,19], the semantics of multi-adjoint normal logic programs follows the philosophy of the stable models semantics [20]. Next, the notion of L-interpretation is recalled.

Definition 3.

Given a complete lattice , a mapping , which assigns a truth-value of L to each propositional symbol, is called L-interpretation. The set of all L-interpretations is denoted as .

We will use the word interpretation instead of the term L-interpretation if there is no room for confusion. The evaluation of a formula under an interpretation I, denoted as , proceeds inductively, until all propositional symbols in are evaluated under I. From now on, we will distinguish between an operator symbol and its associated operator. Specifically, the interpretation of the symbol will be denoted as .

Definition 4.

Given a MANLP and an interpretation , we say that:

- (1)

- A weighted rule is satisfied by I if and only if

- (2)

- I is a model of if and only if all weighted rules in are satisfied by I.

Next, a specific model is given to the multi-adjoint normal logic program in Example 2.

Example 3.

Let be the program defined in Example 2 and consider the interpretation M given by the pairs . It is easy to see that M is a model of , that is, M satisfies all weighted rules in . For instance, the next inequality corresponds to the satisfiability of the rule :

Similarly, the next inequalities, related to the rules , hold as well:

In order to present the notion of the stable model, we need to recall the concept of reduct of a MANLP with respect to an interpretation. Namely, given a MANLP and an interpretation I, the reduct of with respect to I, denoted as , is built by substituting each rule in of the form

by the rule

where the operator is defined as

for all .

Example 4.

Coming back to the MANLP defined in Example 2 and taking into account the interpretation employed in Example 3, the reduct of with respect to M, denoted , is defined as:

Definition 5.

Given a MANLP and an interpretation I, we say that I is a stable model of if I is the least model of .

Notice that, since is a multi-adjoint logic program without negations, there exists the least model of [1]. Hence, stable models are well-defined, that is, the reduct has a least model.

As shown in [14], the continuity of the operators in the rules of a MANLP provides a sufficient condition for the existence of stable models.

Theorem 1.

Let be a multi-adjoint lattice with negation, where K is a non-empty convex compact subset of an euclidean space, and be a finite MANLP defined on this lattice. If , ¬ and the aggregator operators in the body of the rules of are continuous operators, then has at least a stable model.

This theorem ensures the existence of stable models of the program in Example 2.

Example 5.

Clearly, the interval is a convex compact set and , ¬ are continuous operators. Hence, applying Theorem 1, we can assert that the multi-adjoint normal logic program in Example 2 has at least a stable model. For instance, the interpretation given in Example 3 is the least model of the reduct . Hence, by definition, M is a stable model of .

2.2. Core Fuzzy Answer Set Programming

A core language for fuzzy answer set logic programming was introduced in [16], as a simple basic framework in which one can express many of the existing fuzzy answer set programming extensions in the literature, as shown in the aforementioned paper.

In what follows, we recall the syntax and the semantics of core fuzzy answer set programs. Namely, the semantics of core fuzzy answer set programs is stated in terms of the notion of the answer set. In this framework, the elements with the role of propositional symbols are called atoms.

Definition 6

([16]). Let be a set of atoms, a complete lattice and ¬ a negation operator. A core literal is either an atom , a value from , or a formula , where l is a core literal.

Although atoms in core fuzzy answer set programs play the role of propositional symbols in multi-adjoint normal logic programs, in contrast to multi-adjoint normal logic programs, core literals may have the form , being a an atom.

From now on, if there is no room for confusion, we will just use literal instead of core literal.

Definition 7.

Let be a set of atoms, a complete lattice and ¬ a negation operator. A core fuzzy answer set program (CFASP) is a finite set of rules of the form:

being a an atom, an order-preserving mapping in all arguments, literals and ← a residuated implication. A CFASP is called simple if it only contains non-negated literals.

The element a is usually referred to as the head of the rule r, while is called its body. In addition, the set of atoms occurring in a CFASP is denoted as , while the set of literals is denoted as .

An example of the core fuzzy answer set program is given next.

Example 6.

Let ∗ be the usual product operator in , max the maximum operator, ¬ the negation operator given by

for each , and ← any residuated implication. Consider the complete lattice , being ≤ the usual order in , and the set . The following five rules form a CFASP, which will be denoted as :

In fact, given the mappings and the mappings defined, for each , as , , and , we straightforwardly obtain that they all are order-preserving mappings. Therefore, is well-defined, that is, it is actually a CFASP.

The notion of interpretation is crucial for introducing the semantics of CFASP, as usual.

Definition 8.

Given a CFASP on a complete lattice , an interpretation is any mapping .

An interpretation I is extended as usual to the set of formulas in [16]. Although this extension was also denoted by I, considering a clear abuse of notation, in order to be consistent with the notation we use in this paper, we will denote the extension of an interpretation I in CFASP as .

A literal is evaluated under an interpretation I as , whilst for each . Furthermore, the evaluation of a rule under an interpretation I is carried out extending in a natural way the interpretation of each literal appearing in the rule. That is, given a rule r of the form

we obtain that

The semantics of CFASPs is based on the notion of the answer set. The first notions appearing in [16] are the definitions of satisfiability and model, which are given as usual.

Definition 9.

Let be a CFASP. An interpretation I of satisfies a rule if . A model I of is any interpretation that satisfies all rules appearing in .

In the following example, an interpretation is presented, which satisfies different rules but it is not a model of the program in Example 6.

Example 7.

Let be the CFASP described in Example 6 and consider the interpretation defined from the following set of pairs

Clearly, rule is trivially satisfied, since

where the last equality follows from Remark 1. Moreover, making the corresponding computations, rule is satisfied as well. The computations will be displayed with 2-digit precision. This criterion applies throughout the document.

Nevertheless, rule is not satisfied by the interpretation I, as shown below.

Since , rule is not satisfied, and therefore I is not a model of the CFASP .

It needs to be stressed that the residuated implications appearing in the rules of a CFASP could be different. Nevertheless, as we will see next, this is meaningless from a semantical point of view. In other words, the satisfiability of a rule in a CFASP does not depend on the residuated implication. More specifically, given a rule

and an interpretation I, by definition, I satisfies r if and only if

As ← is a residuated implication, the previous expression is equivalent to

Clearly, the operator ← is not involved in Equation (1), and thus it does not affect to the satisfiability of the rule r. As a consequence, we can actually make use of any residuated implication to define the corresponding CFASP of a MANLP. In particular, we can employ the same residuated implication for all rules. In what follows, the definition of the answer set for a simple CFASP is recalled.

Definition 10.

Let be a simple CFASP. An interpretation I of is called an answer set of if I is the least model of .

Next, the notion of the Gelfond–Lifschitz reduct [20] is adapted into this framework.

Definition 11.

Let be a CFASP and I an interpretation of . The reduct of a literal l with respect to I is defined as if and if l is a negated literal. The reduct of with respect to I is defined as the simple program built from the set of rules

where .

Finally, the definition of answer set in a general CFASP is given.

Definition 12.

Let be a CFASP. An interpretation I of is called an answer set of if I is the answer set of the reduct .

Example 8.

Coming back to Example 7, the interpretation I does not satisfy the rule , and therefore I is not a model of . Now, notice that there is no negated literal in rule . As a consequence, its corresponding rule in the reduct is rule itself. Hence, we can assert that I is not a model of , and thus we can conclude that I is not an answer set of .

3. From MANLP to CFASP

The translation procedures and results presented in this section will show that it is possible to translate a multi-adjoint normal logic program into a semantically equivalent core fuzzy answer set program.

Notice that, apart from composition of negations in CFASPs, the syntax of MANLPs and CFASPs differ in the presence or absence of weights in the rules and the effective consideration of different residuated implications in the rules. Indeed, to convert a MANLP into a CFASP, an alternative consists of including the weight of each rule in its body by means of the conductor residuated to the implication which defines the rule. This procedure is formalized as follows.

Definition 13.

Let be a MANLP on . The corresponding CFASP of is defined as the following set of rules:

where ← is any fixed implication of the set .

Notice that, for each rule , taking into account the syntax of multi-adjoint normal logic programs, the operators and @ are order-preserving. As a consequence, the mapping defined as

is order-preserving, being core literals. Thus, the CFASP is well-defined.

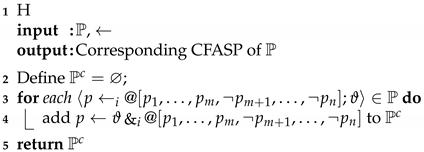

According to Definition 13, Algorithm 1 details stepwise the translation of a MANLP into its corresponding CFASP, where a residuated implication ← in is fixed.

| Algorithm 1: Corresponding CFASP of a MANLP |

|

As shown next, the corresponding CFASP of a MANLP, given by Definition 13, is semantically equivalent to the original program. In other words, the answer sets of the former coincide with the stable models of the latter.

Theorem 2.

Let be a MANLP. An interpretation I is a stable model of if and only if I is an answer set of the corresponding CFASP of .

Proof.

Let I be an interpretation. According to the definitions of stable model and answer set, we need to prove that I is the least model of the reduct if and only if I is an answer set of the reduct . Notice that, to prove the previous statement, it is sufficient to demonstrate that any interpretation J is a model of if and only if J is a model of , since this fact implies that the models of coincide with the models of .

By definition, for each rule in of the form

there exists a rule in the reduct given by

with , and a rule in the reduct of the form

that is

Furthermore, all rules in and are of that form. Notice that, an interpretation J satisfies a rule in of the form

if and only if

Equivalently, according to the definition of ,

Since forms an adjoint pair, the previous inequality can be rewritten as

which is equivalent by Remark 1 to

In other words, J satisfies the rule

if and only if it satisfies the rule

As a consequence, an interpretation I is the least model of the reduct if and only if I is an answer set of the reduct . □

Recently, extended multi-adjoint logic programs (EMALPs) were presented in [15] as an extension of multi-adjoint normal logic programs. In this setting, a special type of aggregator operator, called extended aggregator, is considered in the body of the rules and a new kind of rules, called constraints, have been included in the programs.

As shown in [15], extended aggregators can be used to simulate multiple negation operators or, in general, any kind of order-reversing behaviour for a propositional symbol. Additionally, the consideration of constraints enables a user to impose upper bounds to certain formulae. This shed lights on the flexibility and the expressive power of the extended multi-adjoint logic programming framework. Besides presenting the syntax and the semantics of extended multi-adjoint logic programs, a procedure to translate an EMALP into a semantically equivalent MANLP was provided in [15].

As a result, we can assert that Definition 13 together with Theorem 2 completes the labour initiated in [15]. Namely, we can make use of extended multi-adjoint logic programs in order to model real-world problems, and then translate them into CFASPs to handle compact simple programs with the same meaning. This finished translation provides certain advantageous properties. For instance, from a computational point of view, CFASPs are easier to implement and to reason about, as highlighted in [16].

The next example illustrates how Definition 13 is employed to translate a MANLP into a CFASP, taking into account Algorithm 1. Specifically, we conclude the transformation started in Examples 16, 21 and 26 in [15].

Example 9.

Let be the multi-adjoint lattice where , and are Gödel, product and Łukasiewicz adjoint pairs, respectively, and the negation operators defined as and , for all . Consider the MANLP given by

where is defined, for each , as

Applying Algorithm 1, consider fixed the implication and let . For the rule , that is, the rule

we include in the rule

Similarly, the rule is transformed into the rule

Following this process for the rest of rules of , we conclude that its corresponding CFASP is defined as the set of rules:

Notice that, the CFASP is clearly simpler than the MANLP , from a syntactical point of view.

Applying Theorem 2, we can assert that is semantically equivalent to . For instance, as shown in Example 26 in [15], is a stable model of the MANLP , from which we conclude that N is also an answer set of .

4. From Core Fuzzy Answer Set Programs to Multi-Adjoint Normal Logic Programs

The semantics of core fuzzy answer set programs is defined in terms of answer sets. Sufficient conditions to ensure the existence of answer sets are then instrumental in order to define the semantics of a CFASP. In this section, we provide a method to transform a CFASP into a semantically equivalent MANLP. One of the consequences of that procedure is the possibility of applying different results given in MALP and MANLP, such as the termination results introduced in [8,9] or Theorem 1 to guarantee the existence of answer sets.

Notice that, there are two requirements to translate a CFASP into a MANLP:

- (i)

- The mappings in the body of the rules must be aggregator and/or negation operators. However, this is straightforwardly verified, according to the syntax of CFASPs.

- (ii)

- Composition of negations, that is, literals of the form , are not allowed in MANLPs. In order to deal with this, in what follows, we devise a procedure to transform composited negations into a single negation.

Consider a rule r of the form with . The idea of the proposed method is introducing three new atoms (or propositional symbols) , and in order to represent the information given by :

- is equivalent to

- is equivalent to , and thus to

- is equivalent to , and thus to

Notice that, the three previous statements can be modelled by the rules

respectively. Hence, the rule r could be replaced by the rule

together with rules , and .

In order to formalize the preceding approach, we will fix some notation. First and foremost, notice that we can assume without loss of generality that, for each rule in a CFASP and , is either an atom or a negated literal. Otherwise, if , then we consider the rule where .

Now, given a CFASP and , we say that the degree of b is the highest non-negative integer k such that appears in the body of some rule of , being the k-th composition of the operator ¬. From now on, the set of atoms of with degree will be denoted as .

Once the required notation has been introduced, the corresponding MANLP of a CFASP can formally be defined.

Definition 14.

Let be a CFASP defined with a residuated implication ←. The corresponding MANLP of is defined on the multi-adjoint lattice with negation , being an adjoint pair, as the following set of rules:

where the operator coincides with f and

for each .

It is important to highlight that, given a rule , since f is an aggregator operator, the corresponding operator is also an aggregator. Furthermore, according to the syntax of CFASPs, ← is a residuated implication, and thus there exists an operator & such that is an adjoint pair. Hence, the program is well-defined, that is, is a MANLP. Notice that, when a CFASP is simple (Definition 7), then the obtained multi-adjoint program is a MALP.

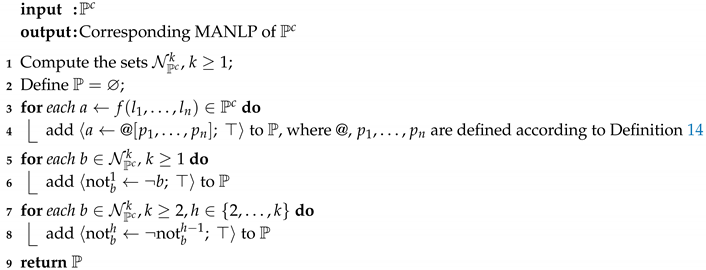

Algorithm 2 shows how Definition 14 is applied in order to compute the corresponding MANLP of a CFASP.

| Algorithm 2: Corresponding MANLP of a CFASP |

|

Example 10.

Consider the CFASP given in Example 6, consisting of the rules

In what follows, we compute the corresponding MANLP of by means of Algorithm 2. Notice that, the degree of p and t is 0, the degree of q and u is 1 and the degree of s is 2. Hence, by definition, and .

Let . According to lines 3 and 4, the rule is included in as

In what regards the rule , it is included in as

Similarly, the rules are adapted to be added to .

Concerning lines 5 and 6, as and , the next rules are added to :

Finally, applying lines 7 and 8, we conclude adding into the rule

Therefore, the corresponding MANLP of is defined on the multi-adjoint lattice with negation , and consists of the following rules:

Now, we will present a technical result which will be useful in order to show the relationship between the answer sets of a CFASP and the stable models of its corresponding MANLP .

Lemma 1.

Let be a CFASP, the corresponding MANLP of , , two interpretations and we define as if and for each . Then, is a model of the reduct if and only if is a model of the reduct , where M denotes the interpretation .

Proof.

Taking into account that forms an adjoint pair, the following statements hold:

- (i)

- satisfies the rule in the reduct if and only if .

- (ii)

- satisfies a rule of the form in the reduct if and only if .

Notice that, the equalities and are satisfied. As a consequence, by definition of and M, we obtain that straightforwardly satisfies all rules in with head , with .

Now, note that a rule belongs to if and only if the rule belongs to . Since every is a “positive” propositional symbol, with , we can assert that the rule given by

is in the reduct if and only if the rule r defined as

belongs to . In what follows, we show that satisfies the rule if and only if satisfies the rule r. Clearly, satisfies if and only if , or equivalently

On the other hand, satisfies r if and only if , i.e.,

We will see that Equations (6) and (7) are identical. Indeed, as for each , the right-hand side of both inequalities coincide.

Now, given , suppose that . Then and , from which . On the contrary, assume that with and . In that case, and . Hence, the following chain of equalities hold:

Note that , and thus .

The following result shows that the answer sets of a CFASP are associated with a family of stable models of its corresponding MANLP .

Theorem 3.

Let be a CFASP, the corresponding MANLP of , an interpretation and given by if and for each . Then, is an answer set of if and only if M is a stable model of .

Proof.

By Lemma 1, we straightforwardly obtain that is a model of if and only if M is a model of . It remains to demonstrate that is the least model of if and only if M is the least model of . We will proceed by reductio ad absurdum. Suppose that M is the least model of but there exists a model of such that , that is, for each and there exists such that . According to Statement (1), the interpretation is then a model of . By definition of and M, we obtain , for each , and , for each . Furthermore, . Therefore , in contradiction with the hypothesis, since M is the least model of .

Suppose now that is the least model of but there exists a model of such that . Hence, we can consider the interpretation defined as , for each . Clearly, if , for some , then N does not satisfy the rule in the reduct . Therefore, we can assert that there exists such that and so, . Now, we consider the interpretation defined as , for each and , for all . Since N is a model of , then satisfies all rules in and so, is also a model of . Thus, by Lemma 1, we obtain that is a model of , contradicting the fact that is the least model of . □

The subsequent theorem completes the foundations of the equivalence between the semantics of a CFASP and its corresponding MANLP . Specifically, it states that the evaluation of under any stable model M of is equal to . As a result, we conclude that Theorem 3 covers all stable models of , and thus and are equivalent, from a semantical point of view.

Theorem 4.

Let be a CFASP and the corresponding MANLP of . Any stable model M of satisfies , for each .

Proof.

Let M be a stable model of , i.e., the least model of the reduct . We will proceed by induction on h.

Base case: We show that , for each .

Since M is a model of the reduct , M satisfies the rule in , and therefore . Furthermore, since M is actually the least model of and is the unique rule with head in , we conclude that , for each .

Inductive step: We assume is satisfied, for some , and we show that holds.

By an analogous reasoning to the base case, M satisfies the rule in , from which . Again, as M is the least model of and is the unique rule with head in , we obtain that must be equal to . Now, taking into account the induction hypothesis, we deduce the required equality:

which finishes the proof. □

As a consequence of Theorems 3 and 4, given a CFASP and its corresponding MANLP , the number of answer sets of coincides with the number of stable models of .

Corollary 1.

Let be a CFASP and its corresponding MANLP. Then, there exists an answer set of if and only if there exists a stable model of .

Proof.

It straightforwardly follows from Theorems 3 and 4. □

Corollary 1 leads us to assert that, if one guarantees the existence of a stable model of , then the existence of an answer set of is ensured. As a result, Theorem 1 can be used to provide a sufficient condition for the existence of answer sets of a CFASP. In particular, the following result is obtained.

Corollary 2.

Let be a CFASP. If the order-preserving mappings and the negation operator involved in the rules of are continuous operators, then there exists at least an answer set of .

Proof.

Assume that the operators in the rules of are continuous. Taking into account the definition of the corresponding MANLP of and Theorem 1, we deduce that has at least a stable model. By Corollary 1, we conclude that has at least an answer set. □

This section concludes with an example in order to illustrate Corollary 2 and Theorems 3 and 4. More precisely, we retrieve the CFASP introduced in Example 6 and we ensure the existence of at least an answer set of . Then, we construct a stable model of its corresponding MANLP and we translate it into an answer set of .

Example 11.

In Examples 6 and 10, the negation operator ¬ in the CFASP is clearly continuous. Furthermore, , , and are continuous mappings as well. Hence, Corollary 2 leads us to conclude that there exists at least an answer set of . For instance, consider the interpretation

Since the corresponding MANLP of was already shown in Example 10, the reduct of with respect to I, denoted as , is given by the following rules:

As there are no rules in with head u, we can assert that the least model M of satisfies . Moreover, as q, s, t, , , and appear in the head of only one rule, specifically in the head of , , , , , and , respectively, then:

Finally, the value assigned to p by M is computed as follows:

As I coincides with M, we conclude that I is the least model of . In other words, I is a stable model of . Hence, applying Theorem 3, I is an answer set of .

5. Conclusions and Future Work

We have presented a methodology to simulate an arbitrary MANLP by means of a semantically equivalent CFASP. We proposed the inclusion of the weight of each rule appearing in a given MANLP in its body, by using the residuated pair, which defines the rule. This procedure allows us to complete the labour initiated in [15], that is, extended multi-adjoint logic programs can be translated into CFASPs with the goal of handling compact simple programs, which are semantically equivalent. This fact considerably increases the potential of EMALPs to model real-life problems, since modelling the information contained in a text or in a database by decision rules and the interpretation of those rules will be easier through a EMALP and its translation into a CFASP will facilitate the simulation and computation of the consequences/deductions from the program.

We have also studied the opposite translation procedure, that is, a mechanism to translate an arbitrary CFASP into a semantically equivalent MANLP has been given. The proposed translation method increases the number of rules of the original program, since it transforms the composited negations appearing in a given CFASP into a single negation, by including new rules with new propositional symbols. From this mechanism, we have established a one-to-one correspondence between the answer sets of a CFASP and the stable models of its corresponding MANLP. Indeed, we have proven that Theorem 1, introduced in [14], provides sufficient conditions under which the existence of answer sets of a CFASP can be ensured.

As future work, other results given in MALP and MANLP will also be considered, such as the termination results given in MALP [8,9] and the studies on coherent and incoherent information in MANLP [21,22]. In addition, we will study the extension of EMALP with the consideration of disjunctions in the head of the rules. Furthermore, we would like to apply the translation mechanisms and the theoretical advances achieved in this work to solve real-life problems. Specifically, we are interested in investigating the potential of their application to the digital forensics field, where the developed theory can be useful to extract knowledge with the goal of modelling behaviour patterns. For instance, in order to detect and prevent fraud related to transactional credit card databases as well as to manage databases containing information about crimes in a certain city. Due to the large amount of data in digital forensics, the simplicity of CFASPs is very useful to achieve a feasible computational efficiency. On the other hand, these data have a broad variability, for example, it can be given in natural language, and an easy mechanism for translating the data to logic programs is fundamental. In this sense, the high expressiveness potential of EMALPs can support this translation. Thus, both logic frameworks CFASP and EMALP are of great interest for obtaining information from (big) data.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by the 2014–2020 ERDF Operational Programme in collaboration with the State Research Agency (AEI), in project TIN2016-76653-P, and with the Department of Economy, Knowledge, Business and University of the Regional Government of Andalusia in project FEDER-UCA18-108612, by the European Cooperation in Science & Technology (COST) Action CA17124, and by the research and transfer program of the University of Cádiz.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the four anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of the paper and useful suggestions to clarify this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Medina, J.; Ojeda-Aciego, M.; Vojtáš, P. Multi-adjoint logic programming with continuous semantics. In Logic Programming and Non-Monotonic Reasoning, LPNMR’01. Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence 2173; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 351–364. [Google Scholar]

- Damásio, C.V.; Pereira, L.M. Monotonic and residuated logic programs. In Symbolic and Quantitative Approaches to Reasoning with Uncertainty, ECSQARU’01. Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence, 2143; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 748–759. [Google Scholar]

- Vojtáš, P. Fuzzy logic programming. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2001, 124, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcillo, P.J.; Moreno, G. Efficient Unfolding of Fuzzy Connectives for Multi-adjoint Logic Programs. In Interactions Between Computational Intelligence and Mathematics; Kóczy, L.T., Medina, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, G.; Penabad, J.; Riaza, J.A. Symbolic Unfolding of Multi-adjoint Logic Programs. In Trends in Mathematics and Computational Intelligence; Cornejo, M.E., Kóczy, L.T., Medina, J., De Barros Ruano, A.E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Julián, P.; Moreno, G.; Penabad, J. An improved reductant calculus using fuzzy partial evaluation techniques. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2009, 160, 162–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julián-Iranzo, P.; Medina, J.; Ojeda-Aciego, M. On reductants in the framework of multi-adjoint logic programming. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2017, 317, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damásio, C.; Medina, J.; Ojeda-Aciego, M. Sorted Multi-adjoint Logic Programs: Termination Results and Applications. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. 2004, 3229, 252–265. [Google Scholar]

- Damásio, C.; Medina, J.; Ojeda-Aciego, M. Termination of logic programs with imperfect information: Applications and query procedure. J. Appl. Logic 2007, 5, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bustince, H.; Madrid, N.; Ojeda-Aciego, M. The Notion of Weak-Contradiction: Definition and Measures. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2015, 23, 1057–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, N.; Ojeda-Aciego, M. On the measure of incoherent information in extended multi-adjoint logic programs. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computational Intelligence (FOCI), Singapore, 16–19 April 2013; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, J.; Ojeda-Aciego, M.; Vojtáš, P. Similarity-based unification: A multi-adjoint approach. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2004, 146, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strass, H.; Muñoz-Hernández, S.; Pablos-Ceruelo, V. Operational Semantics for a Fuzzy Logic Programming System with Defaults and Constructive Answers. In Proceedings of the Joint 2009 International Fuzzy Systems Association World Congress and 2009 European Society of Fuzzy Logic and Technology Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, 20–24 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo, M.E.; Lobo, D.; Medina, J. Syntax and semantics of multi-adjoint normal logic programming. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2018, 345, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, M.E.; Lobo, D.; Medina, J. Extended multi-adjoint logic programming. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2020, 388, 124–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.; Schockaert, S.; Vermeir, D.; De Cock, M. A core language for fuzzy answer set programming. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2012, 53, 660–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Madrid, N.; Ojeda-Aciego, M. Towards a fuzzy answer set semantics for residuated logic programs. In Proceedings of the Web Intelligence/IAT Workshops, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 9–12 December 2008; pp. 260–264. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nieuwenborgh, D.; De Cock, M.; Vermeir, D. An introduction to fuzzy answer set programming. Ann. Math. Artif. Intell. 2007, 50, 363–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Madrid, N.; Ojeda-Aciego, M. On the existence and unicity of stable models in normal residuated logic programs. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2012, 89, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfond, M.; Lifschitz, V. The stable model semantics for logic programming. ICLP/SLP 1988, 88, 1070–1080. [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo, M.E.; Lobo, D.; Medina, J. Selecting the Coherence Notion in Multi-adjoint Normal Logic Programming. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2017, 10305, 447–457. [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo, M.E.; Lobo, D.; Medina, J. Measuring the Incoherent Information in Multi-adjoint Normal Logic Programs. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2018, 641, 521–533. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).