1. Introduction

Recently, against the background of complication of designing industrial products, the necessity of coupled simulation of plural phenomena according to different equations has increased. To carry out such simulations, first, it is necessary to construct and discretize appropriate mathematical models before numerical calculations. However, even if the equations for individual phenomena are known, naive combination of the equations easily results in violating important law of physics such as the energy-conservation law [

1,

2].

In this paper, we propose energetic-property-preserving numerical schemes for coupled models of two given natural systems. Popular models for coupled systems are the Port-Hamiltonian systems [

3]. From the viewpoint of geometric mechanics, in this approach, the equations are described by using the Dirac structure, which is a geometric structure generalized from the symplectic structure and the Poisson structure [

4]. This structure describes the energy transfer between the systems, thereby deriving the model equation in such a way that the energetic property of the coupled systems is preserved. It is also known that the resultant coupled system is also port-Hamiltonian and hence models for large coupled systems can be derived in a systematic way. In addition, the Lagrangian formalism of this approach is also reported [

5,

6,

7].

Regarding numerical schemes for the port-Hamiltonian systems, energy-preserving and passivity-consistent numerical schemes were proposed by Celledoni and Høiseth [

8]. Focusing on a discrete energy balance equation and the stability under interconnection, Celledoni and Høiseth proposed a definition of discrete port-Hamiltonian systems. Port-Hamiltonian systems are typically written as

where

is the state variables,

is the input, and

is the output.

is a skew-symmetric matrix, which is often corresponding to the Hamiltonian structure of the underlying systems.

is a

matrix.

is typically an energy function.

is a positive definite matrix, which is corresponding to the dissipation property of the system. For conservative systems,

. In [

8], two conservative systems, one of which is supposed to be given while the other is a controller to be designed, are assumed to be interconnected by

so that the total energy is preserved:

In fact, the above system is shown to be

with a skew-symmetric matrix

C. By using this structure, energy-preserving and passivity-consistent numerical schemes are successfully derived.

In this paper, we consider a slightly different situation where two natural systems are interconnected by the action–reaction law. Natural systems are systems that are derived from Lagrangian defined as the difference between the kinetic energy and the potential energy. This type of coupled systems naturally arise in industrial simulations. The systems under consideration can be infinite dimensional and hence we consider three types of interconnections, that is, those between an ODE and an ODE, a PDE and a PDE, and an ODE and a PDE. As explained in

Section 2, due to the action–reaction law, the systems are not always written in the form of Equation (

4). Hence, a different approach to designing energetic-property-preserving numerical method is required for these systems, which we propose in this paper.

This paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we explain the coupled systems and the energy conservation law of these systems. Then, we propose energetic-property-preserving numerical schemes for the coupled systems.

Section 3 deals with the systems consisting of finite dimensional systems and

Section 4 does the systems including infinite ones. Numerical examples are shown in

Section 5.

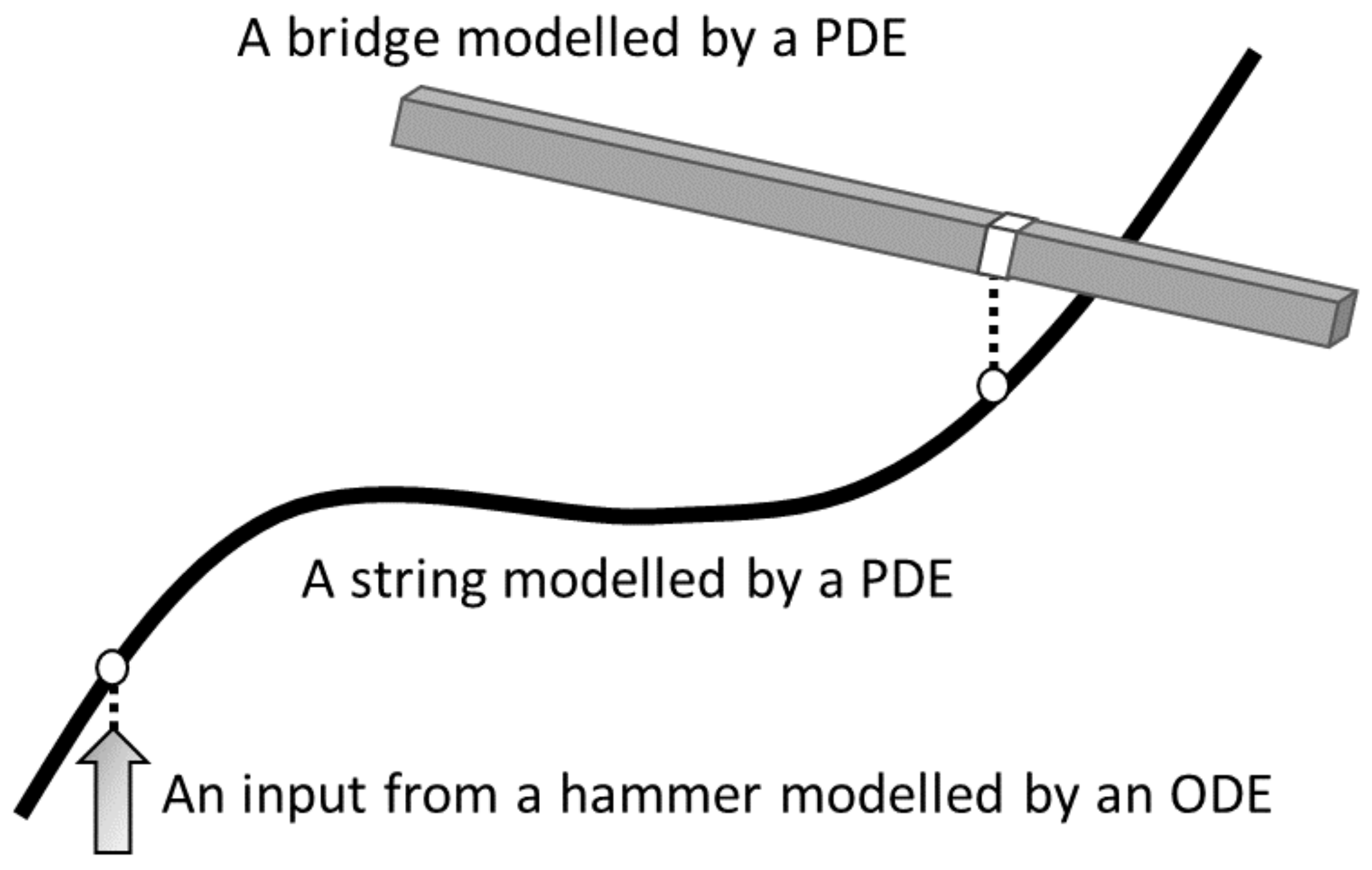

Remark 1. The above three types of coupled systems often appear in industrial simulations. For example, let us consider simulations of the stringed musical instruments, such as the guitar and the piano [9]. The one side of strings of these instruments are typically attached to a bar-shaped part of the instruments, which is called the bridge. Each string and the bar are modeled as infinite-dimensional natural systems and they are in contact at a single point. Hence, this case corresponds to the interaction between two PDEs. Meanwhile, the strings of the piano are excited by the hammer, which is modeled as the interaction between a wave-type PDE (a model of each string) and a mass–spring ODE (a model for the hammer) (see Figure 1). In addition, designing numerical schemes for the above two cases often reduces to the case of interconnections between two ODEs by semi-discretization in space (cf. Section 4). 2. Interconnection of Natural Systems

In this paper, we consider interconnection of two natural systems with dissipation terms. Natural systems are systems derived from the standard Lagrangian that is defined as the difference between the kinetic energy and the potential energy. For example,

where

m is a constant,

u is the vector of the state variables, and

V is the potential function, is a natural system because this is the Euler–Lagrange equation associated with the Lagrangian

The system in Equation (

5) often arises with the damping term

in which

is a positive semidefinite operator. If

is proportional to the identity operator, the operator

essentially denotes the damping coefficient. For simplicity of notation, regarding

as a 2-form, we often write for vectors or functions

and

or

These are nonnegative if .

Another example of a natural system is the Euler–Lagrange partial differential equation of the following form:

where

is typically the density and

the variational derivative. The variational derivative is the gradient in functional spaces, which is defined by the function that satisfies

is the Fréchet derivative and

is the standard

inner product. In fact, the partial differential Equation (

10) has the Lagrangian

Similar to Equation (

5), Equation (

10) is often accompanied by dissipation terms:

Example 1. For example, the wave equationon the interval under the periodic boundary condition is the Euler–Lagrange partial differential equation, of which Lagrangian is In this example, H isand the variational derivative of this functional isbecause under the periodic boundary condition it follows thatfrom the formal calculation Throughout this paper, we suppose that two natural systems with dissipation terms of the form in Equation (

7) or Equation (

13) are in contact at a single point and through this point the two systems are exerting a force on each other. As noted in the Introduction, we consider the following three cases: interconnections between an ODE and an ODE, a PDE and a PDE, and an ODE and a PDE.

To begin with, we consider the first case. As mentioned above, we assume that systems are interconnected in such a way that the force between each two subsystems is described by the action—reaction law. More specifically, we assume that the coupled model is written in the form

are vectors of state variables which are possibly of different dimensions.

is the

jth unit vector representing the contact point.

f is the scalar function of

t, which we define so that the total energy of this system is preserved when the dissipation terms do not exist. First, the time derivative of the total energy of the system is

Substitution of the equation yields

where

denotes the

ith component of the vector

. In the absence of the dissipation terms, this becomes

Thus, for conservation of the energy

is sufficient. For this condition to be held, we impose that

also for the systems with dissipation terms. From Equation (

20) and the first equality of Equation (

25), we get

which gives

As a result, the coupled model equation is

Remark 2. Equation (28) without the dissipation terms can be written in the Hamiltonian formalism: where B is the matrix that has only 4 non-zero components Because, unfortunately, the matrix B is not skew-symmetric, the equation is not of the form in Equation (4); however, as shown in the next theorem, the total energy is conserved. Theorem 1. Provided thatfor any solutions to the equations of the interconnected systemsthe energy is not increasing: In particular, in the absence of the dissipation terms, that is, , the energy is preserved: Proof. From

ith and

jth elements of Equation (

33), the following equations hold:

Substitution of Equation (

34) into the above yields

which is equivalent to

In the same way, we have

and, hence,

Thus, we get

for all

t. Hence, using the assumption on the initial conditions in Equation (

32), for any

t, we have

Meanwhile, as shown in Equation (

22), the time derivative of the energy is computed as below:

Therefore, from Equation (

38), we obtain

□

In the same way, we can obtain similar theorems for the other two types of the interconnected systems. Firstly, we consider

where

f is a scalar function of

t.

is the Dirac delta function, and hence the equalities in the above equations are in the weak sense; however, the following computations are naively performed for simplicity. The terms with the Delta function represent that the two systems are interconnected at

for the first system and

for the second. For this coupled system, the total energy is defined by

Theorem 2. Suppose that the boundary condition is appropriately imposed so that Provided thatfor any solutions to the equations of the interconnected systemsthe energy is not increasing: In particular, in the absence of the dissipation terms, the energy is preserved: Secondly, we consider

of which the total energy is

Theorem 3. Suppose that the boundary condition is appropriately given so that Provided thatfor any solutions to the equations of the interconnected systemsthe energy is not increasing: In particular, in the absence of the dissipation terms, the energy is preserved: We omit the proofs of Theorems 2 and 3 because they are proved exactly in the same way as Theorem 1.

3. Energetic-Property-Preserving Numerical Schemes for the Finite Dimensional Coupled Systems

In this section, we propose energetic-property-preserving numerical schemes for the above finite-dimensional coupled systems. Although the equation is not of the form in Equation (

4), we use the discrete gradient similarly to CelledoniHøiseth [

8]. A discrete gradient is defined as follows (see, e.g., [

10])

Definition 1. A discrete gradient of a function is defined by a vector valued function such that The first condition is a discrete counterpart of the chain rule

The second condition assures that a discrete gradient is indeed an approximation of the gradient. A discrete gradient is not uniquely determined and hence several ways for designing a discrete gradient have been proposed. A typical way is the average vector field method [

11]:

Another choice for obtaining a discrete gradient is the automatic discrete differentiation, which is a method to automatically derive a discrete gradient in a similar way to the automatic differentiation; see [

12].

In what follows, we use the following symbols for the discrete systems. The step sizes are denoted, for example, by

and

. An approximation of

is denoted by

, where

can be a vector

. Similarly, for partial differential equations, an approximation of

is denoted by

. For simplicity of notation, we also use the following difference operators:

and the averaging operator

Note that the difference operators and the averaging operator commute; for example,

We first consider the coupled system in Equation (

33). For the other two types of systems, the numerical schemes are obtained by replacing the discrete gradient by the discrete variational derivative [

1,

13] or by discretizing the partial differential equation in space in such a way that the resultant semi-discrete scheme becomes a finite dimensional natural system; we discuss this below.

We discretize the Hamiltonian form of Equation (

33)

in the following way:

Under an assumption that corresponds to Equation (

32), this numerical scheme preserves the energetic properties of the systems in the following sense.

Theorem 4. Provided thatfor any solutions to the numerical scheme in Equation (61), the total energy is not increasing: In particular, in the absence of the dissipation terms, that is, , the energy is preserved: Proof. The proof is almost the same as the continuous case. First, from the definition of

, it follows that

and hence

In the same way, we get

from which we have

Therefore, we obtain

and

for all

n from the assumption on the initial conditions in Equation (

62). Meanwhile, the time difference of the discrete energy function is

Substitution of the numerical scheme in Equation (

61) yields

because

. □

4. Energetic-Property-Preserving Numerical Schemes for the Coupled Systems Incorporating the Infinite Dimensional Systems

The numerical scheme for the partial differential Equation (

40) can be obtained in the following way. First, the equation is semi-discretized in space into the ordinary differential equation of the form in Equation (

20), which can be achieved in the straightforward way by discretizing the potential function in space as seen in the following example. For a general method of semi-discretization, see, e.g., [

1,

11,

13].

Remark 3. For example, the wave equation with the wave speed c and the damping coefficient γon the interval under the periodic boundary condition is discretized towhere is an approximation to . This is an ordinary differential equation of the form Second, we need to discretize the term with the Dirac delta function:

Because the delta function is defined by requiring

for any continuous function

g, we need to discretize this functional while satisfying this condition in some sense. A straightforward discretization would be

where

is the integer that has the nearest

to

. A more sophisticated way is first approximating the Dirac function by a continuous function, such as the Gauss function

and then discretizing this function; for example,

with a small

.

is the normalization constant that is defined by requiring

Following the procedure described above, we can semi-discretize the system of the partial differential equations in Equation (

40) into

and Equation (

47) into

where

are vectors that approximate the Dirac functions and

over the symbols denotes approximated values by the semi-discretization. The following theorem is obtained in the same way as shown in

Section 2.

Theorem 5. Provided thatfor any solutions to the semi-discretized schemethe energy is not increasing:where , are 1 or , which are determined depending on whether the system under consideration originates from an ODE or a semi-discretization of a PDE. In the absence of the dissipation terms, the energy is conserved. Remark 4. This theorem shows the energy behaviors of both the system in Equation (74) and the one in Equation (75) because Equation (75) is obtained by setting and in Equation (74) to and ε. Proof. In the same way as before, we have

Hence, the proof is competed if we have

which follows from the assumption in Equation (

76) on the initial conditions and

We show this equality in what follows. Computing the innerproduct of

and the equations for

gives

Substitution of

yields

and hence we get

In the same way, we also have for

and

which shows Equation (

80). □

Theorem 6. Provided thatfor any solutions to the numerical scheme

the total energy is not increasing:

In particular, in the absence of the dissipation terms, that is, , the energy is preserved: Proof. This theorem is obtained in the same way as before. The time difference of the discrete energy function is

Substitution of the numerical scheme in Equation (

82) yields

Thus, the proof is completed if we can show that

which follows from

under the assumption in Equation (

81) on the initial conditions.

From the scheme in Equation (

82) for

, we have

which shows

In the same way, we have

and hence

This shows Equation (

86). □

Remark 5. The accuracy of the proposed schemes depends on the choice of the discrete gradient and also on the spatial discretization if the systems are infinite dimensional. If the discrete gradient is symmetric, then the scheme is second-order accurate in temporal direction because the scheme is also symmetric; otherwise, the scheme is first-order accurate. For example, the average vector field method in Equation (56) yields a symmetric discrete gradient. As for the spatial direction, the accuracy mainly depends on the discretization of the Dirac delta function; however, since the equations are discretized by using the finite difference method, it is actually difficult to determine the accuracy of the discretization of this functional because the Dirac delta function does not admit the standard Taylor expansion. For precise analysis, the finite element method should be applied. Remark 6. Because the above schemes are implicit, they are stable but computationally expensive. There are several techniques to reduce the computational effort for solving the system of equations, which arises from the implicit scheme. For example, the predictor–corrector method proposed in [1] deserves consideration. 5. Numerical Example

In this section, we show two numerical examples. The first example is a coupled system that consists of the wave equation and the elastic equation

under the boundary conditions

The total energy of this system is

Following Equation (

61), we discretize these equations into

where we use for simplicity the same step size

and

for both systems and

and

correspond to the interconnecting points:

.

and

are the vectors that consist of

s and

s.

and

are the difference matrix defined by

which are the approximations of

by the central difference operators under the boundary conditions in Equation (

90). Without the dissipation terms, each of these discrete systems is the Hamiltonian equation of which energy function is, respectively,

where

and

are the numbers of the nodes.

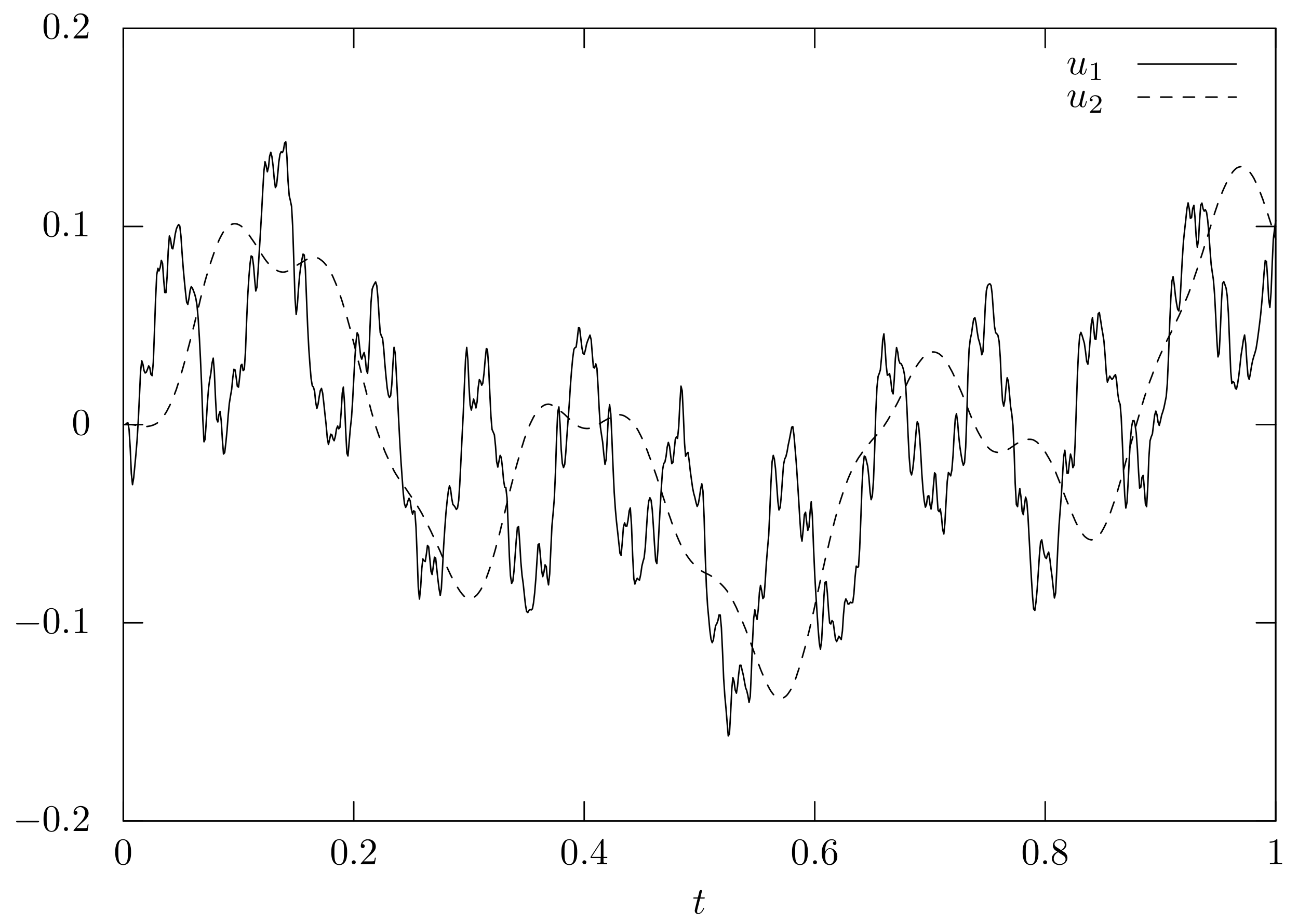

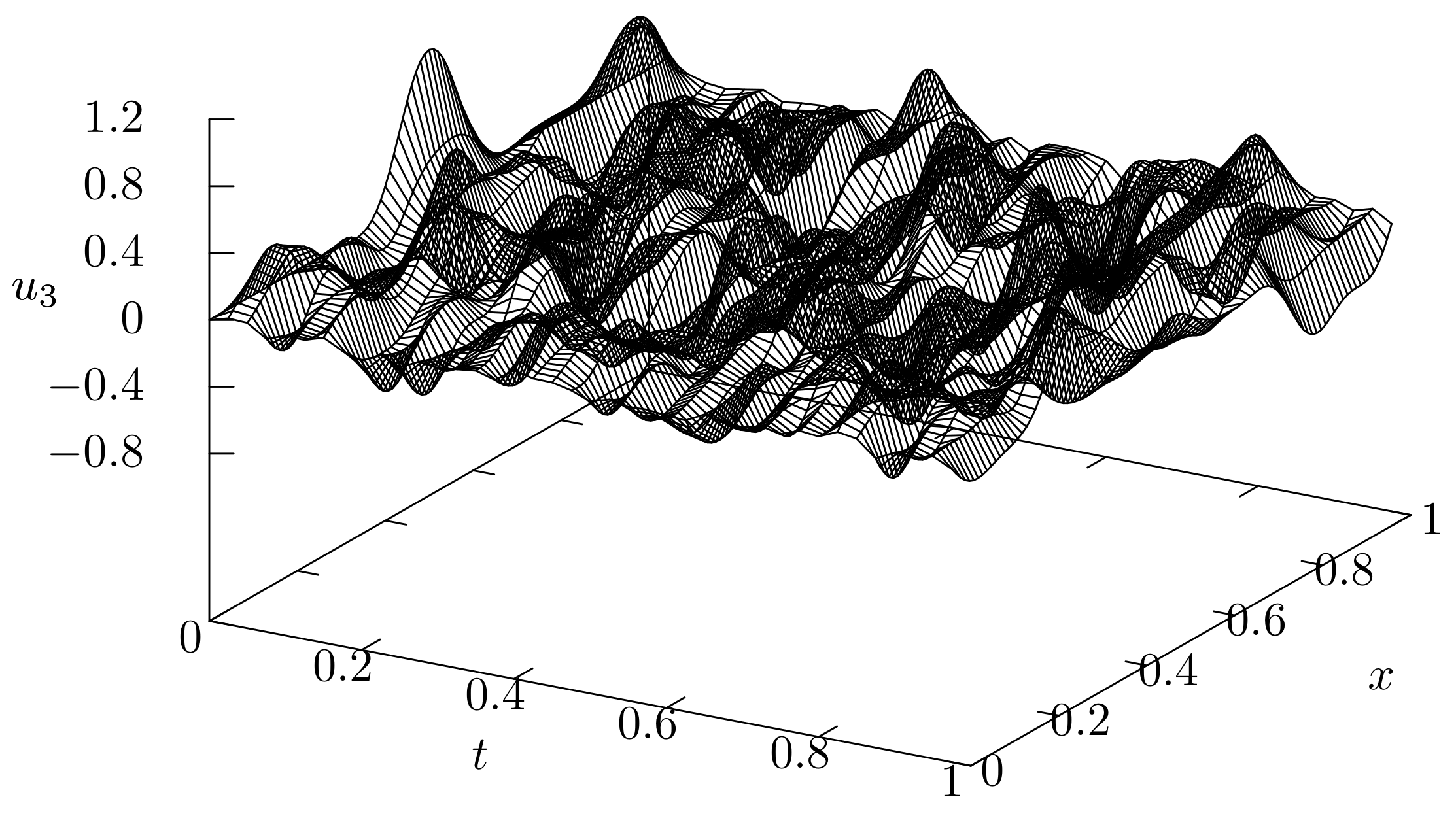

We set

,

,

. The initial conditions are set as

The positions of the interconnection are

. We first set the damping coefficients

and

to 0. The numerical solution from

to

are shown in

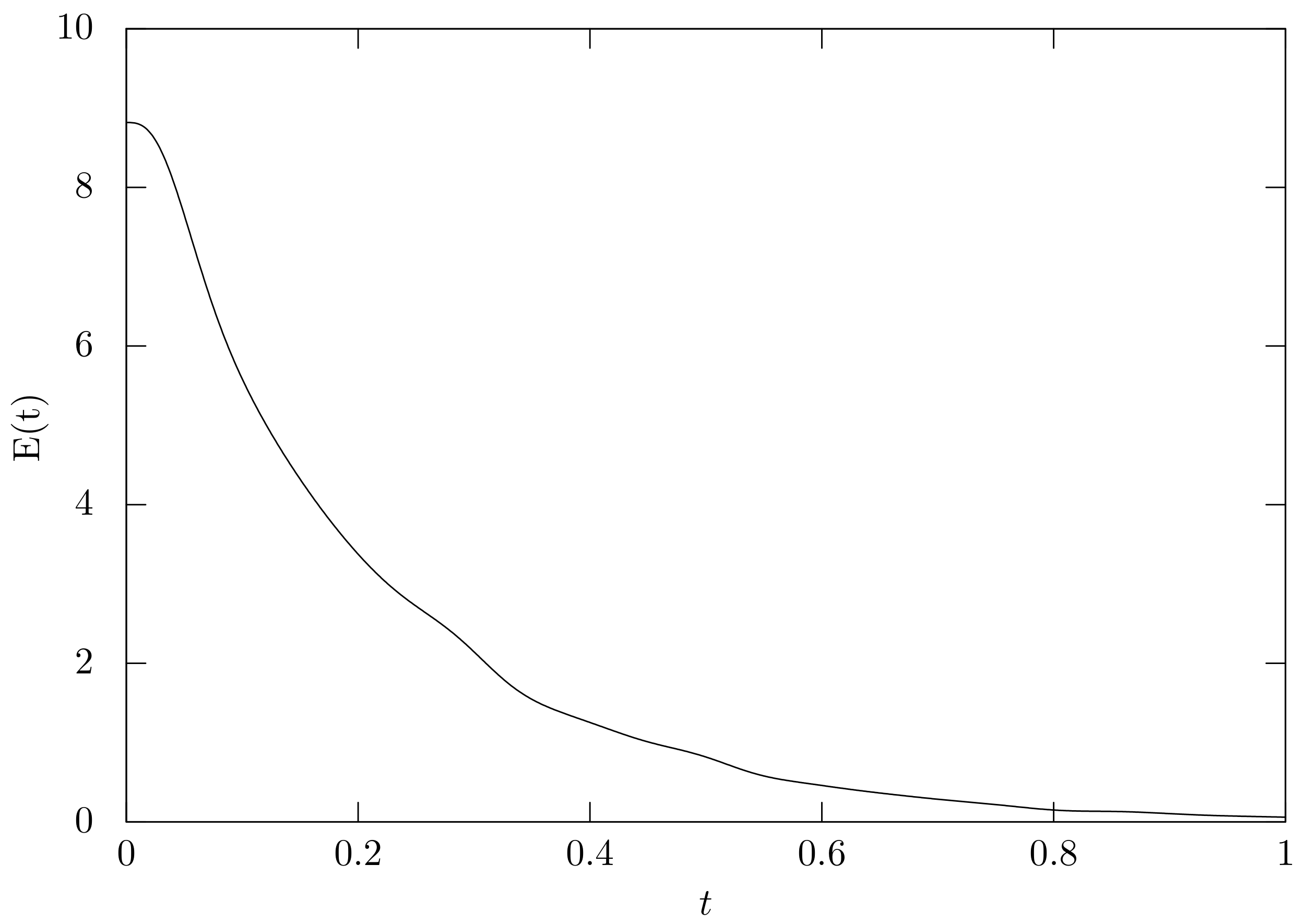

Figure 2 and

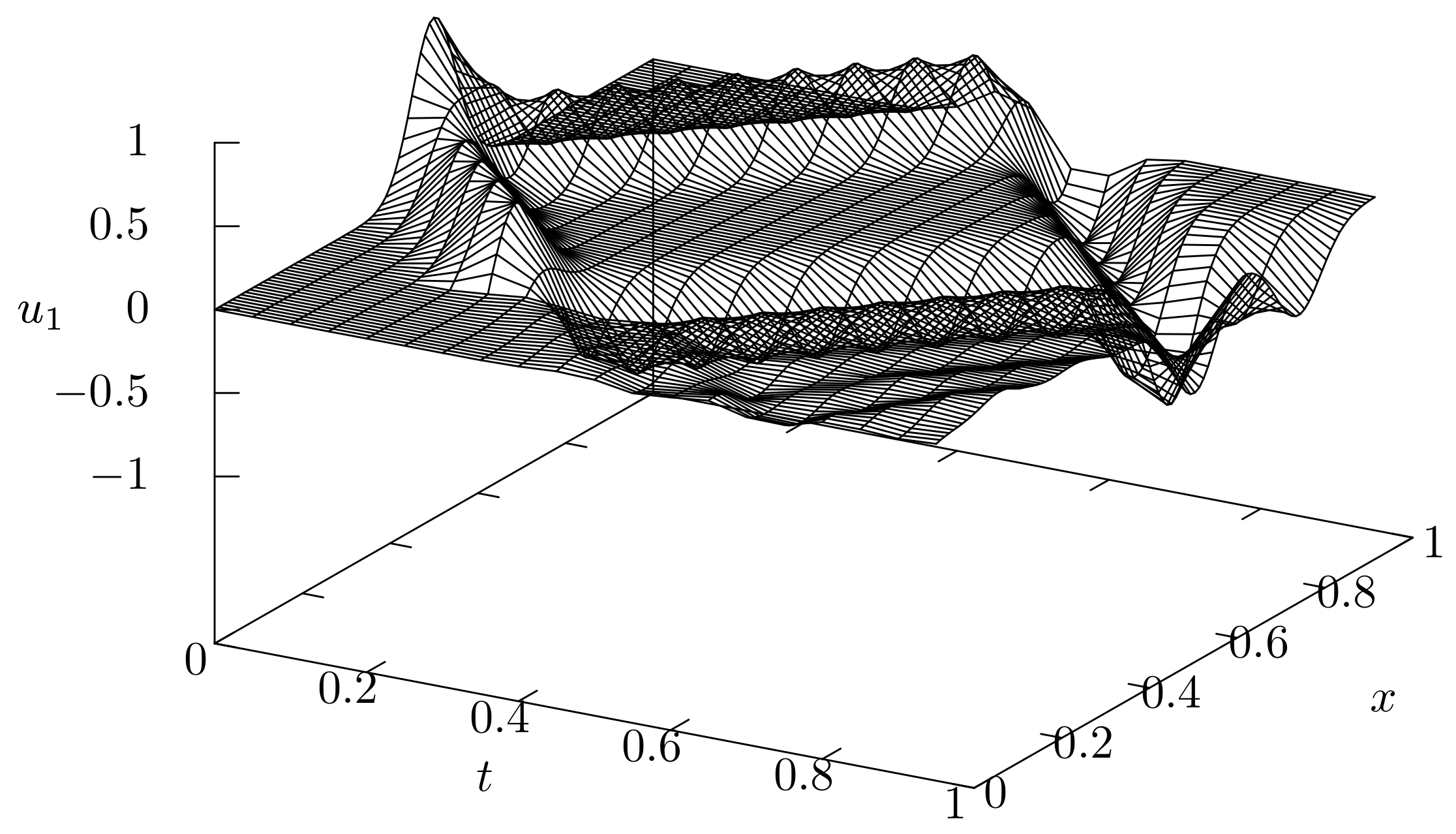

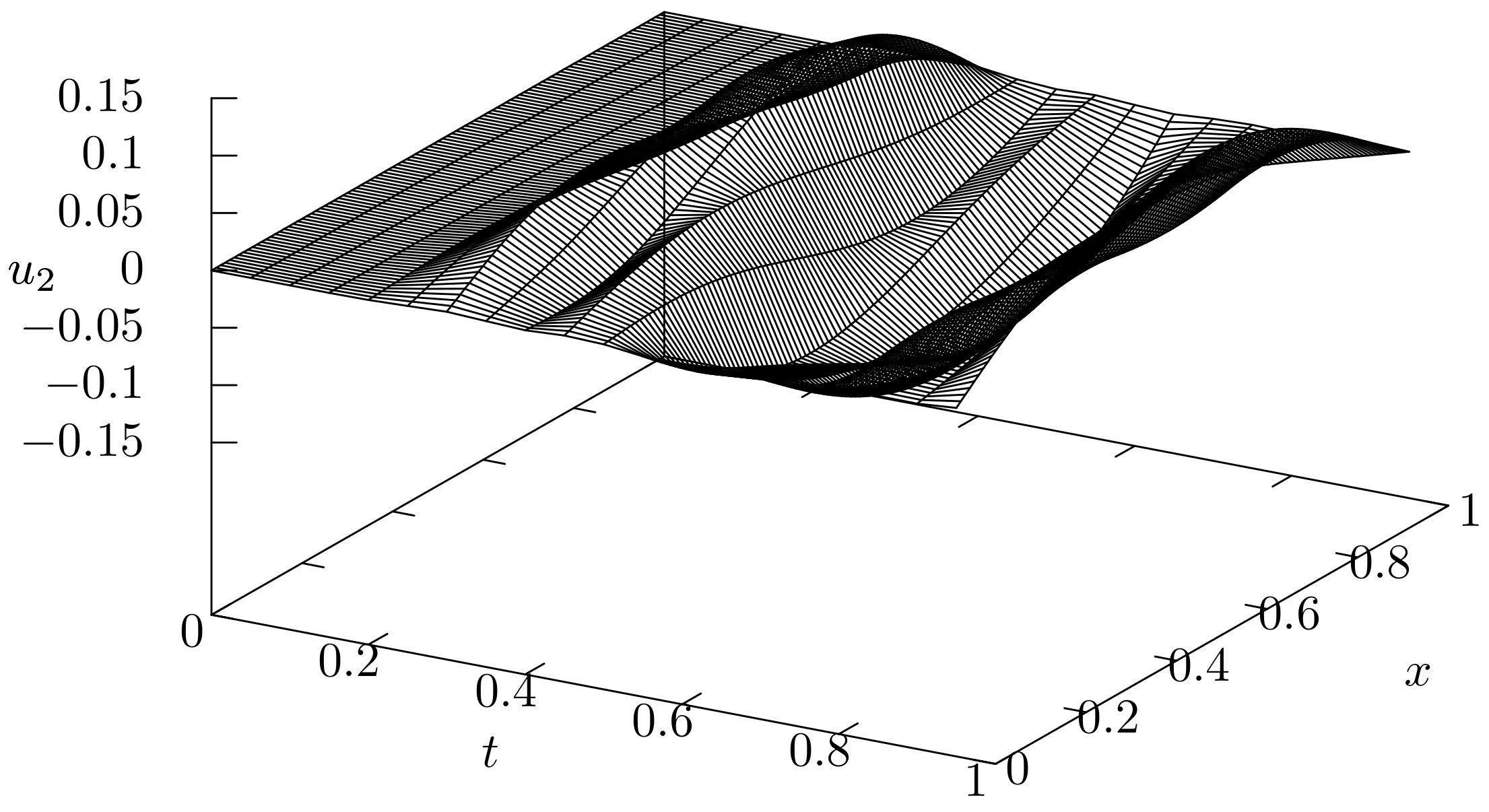

Figure 3. We observe that the wave packet shown in the initial state of the wave equation splits and propagates towards the connecting point and the right boundary. Then, at the connecting point, the wave packet is reflected while a slow wave is excited in the elastic equation.

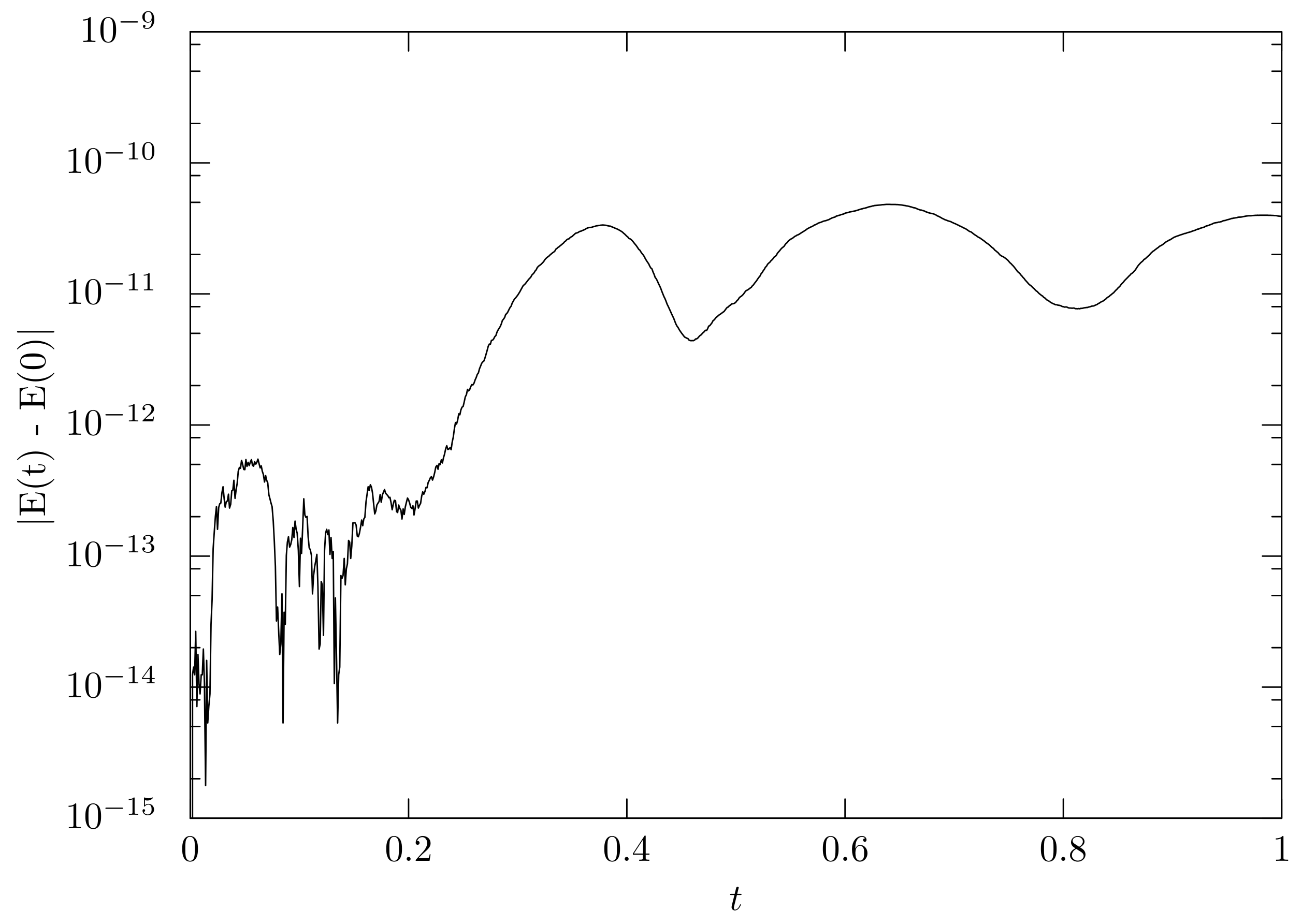

Although this causes an energy exchange, the total energy is preserved up to the rounding errors, as shown in

Figure 4. In addition, in this example, if the energy is bounded, then

,

,

,

,

, and

are all bounded. In fact, the stability of the numerical scheme follows from these conservation laws because combined with the Dirichlet boundary condition and the boundedness of

and

shows that

and

are also bounded from the discrete Poincaré inequality [

13].

Second, we set both the damping coefficients

and

to 10. The numerical solution and the total energy from

to

are shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, respectively. In particular, from the results in

Figure 7, it is confirmed that the total energy is monotonically dissipated.

The second example is a combination of the mass–spring system and the elastic equation:

In this system, one side

of the spring is attached to the elastic rod at

, while the other side

is not constrained. The total energy is

The numerical scheme for this system is

where

l is the connecting point of the elastic equation and the term

is an approximation to the delta function. The boundary condition for the elastic equation is the same as the previous example. The discrete total energy of this system is

N denotes the number of the nodes. The initial conditions are given as

The parameters are set to , and . The elastic equation is solved on the interval and the connecting point is . We set .

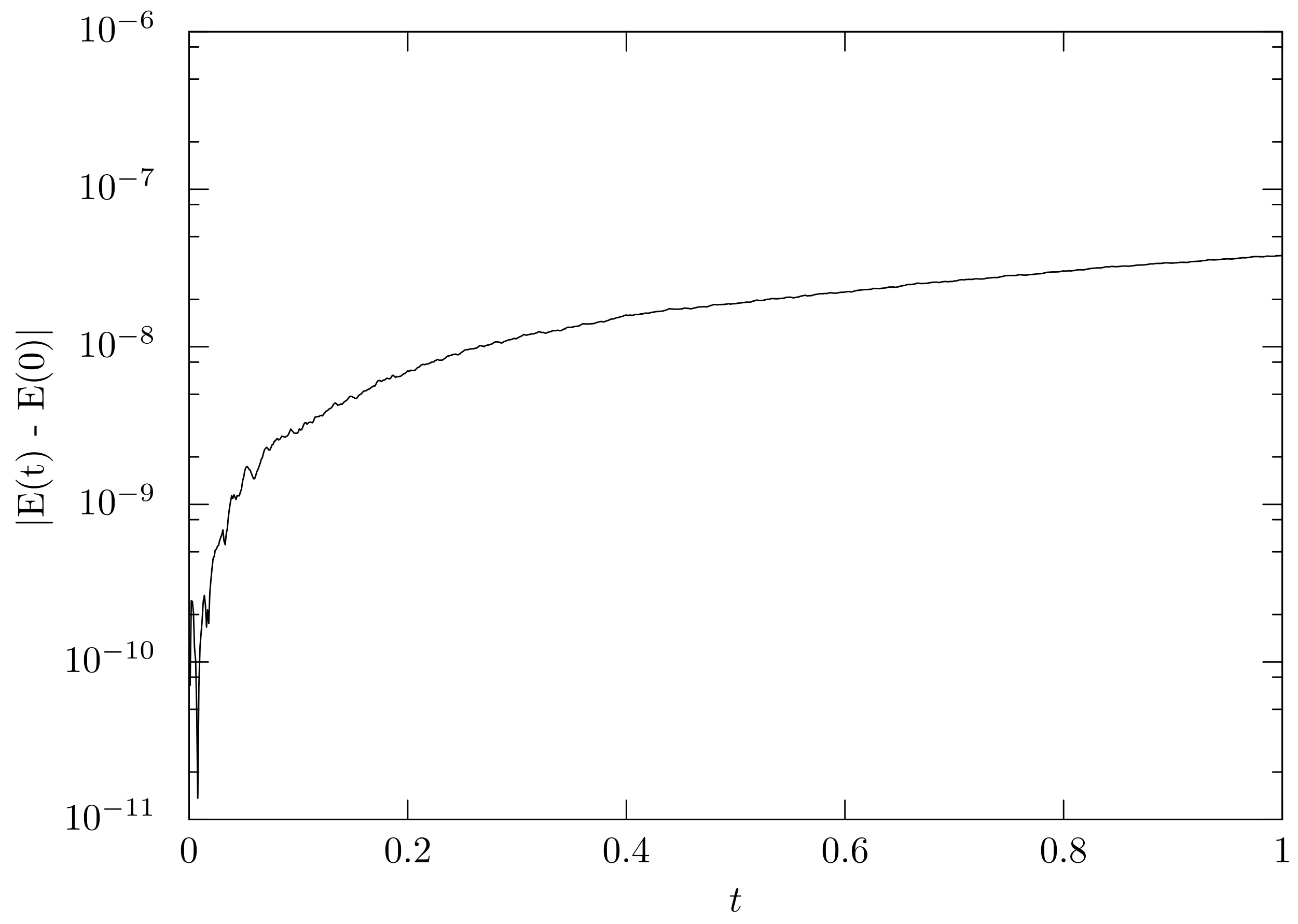

The numerical solutions for the mass–spring system

and

are shown in

Figure 8 and that for the elastic equation

in

Figure 9. In this case, although the state variables of the mass–spring system is set to

at

, they are excited by the energy exchange with the elastic bar through the connecting point. The solution curve of

is interestingly much smoother than that of

; this shows that the mass–spring system serves as a shock absorber. The deviation of the total energy from the initial state is shown in

Figure 10. The total energy is preserved up to the accumulation of the rounding errors.

6. Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we design energetic-property-preserving numerical methods for coupled natural systems. For such methods for coupled systems, Celledoni and Høiseth proposed energy-preserving numerical methods [

8] aiming at controlling port-Hamiltonian systems. In this paper, we consider similar but slightly different models; restricting the target systems to natural systems, we coupled two systems by using the law of action–reaction. When the two systems with no dissipation term are coupled, it is essentially required that the time derivative of the state variables of the two systems are equal at the connecting point for conservation of the total energy. The model and the energetic-property-preserving numerical methods are constructed by determining the interaction between the systems so that this condition holds. As shown in the first numerical experiment, the conservation of energy often leads to the stability of numerical schemes. Such a systematic approach for deriving stable schemes is useful for simulations of large coupled systems because it is generally difficult to derive stable numerical methods for the complex systems.

For future work, the proposed technique should be applied for deriving stable numerical schemes for complicated systems that actually appear in industrial applications. In addition, because the proposed approach in this paper is based on the discrete gradient method, this approach derives implicit methods, which are not often feasible for large-scale systems. Therefore, it is important to develop a method for relaxing the derived implicit schemes to be explicit. For symplectic integrators, Tao proposed a method for rewriting any Hamiltonian system to a separable Hamilton system so that explicit numerical schemes are derived by using the splitting method [

14]. It is desirable to develop explicit energetic-property-preserving numerical methods for coupled systems by using such a method.