Abstract

A mathematical model describing viral dynamics in the presence of the latently infected cells and the cytotoxic T-lymphocytes cells (CTL), taking into consideration the spatial mobility of free viruses, is presented and studied. The model includes five nonlinear differential equations describing the interaction among the uninfected cells, the latently infected cells, the actively infected cells, the free viruses, and the cellular immune response. First, we establish the existence, positivity, and boundedness for the suggested diffusion model. Moreover, we prove the global stability of each steady state by constructing some suitable Lyapunov functionals. Finally, we validated our theoretical results by numerical simulations for each case.

1. Introduction

Viral infections represent a major cause of morbidity with important consequences for patient’s health and for the society. Among the most dangerous, let us cite the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) that attacks immune cells leading to the deficiency of the immune system [1,2], the human papillomavirus (HPV) that infects basal cells of the cervix [3,4], and the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and the hepatitis C virus (HCV) that attack liver cells [5,6,7,8]. Mathematical modeling becomes an important tool for the understanding and predicting the spread of viral infection, and for the development of efficient strategies to control its dynamics [9,10,11,12]. One of the basic models of viral infection suggested by Nowak in 1996 describes the interactions among uninfected cells, infected cells, and free viruses. Nowadays, modeling of viral infection actively develops with a variety of new models and methods [9,10,11,12,13,14,15] (see also the monograph [16] and the references therein). The action of immune system was introduced into the basic model with cytotoxic T-lymphocytes cells (CTL) killing infected cells [12,13,14,15,17,18]. The impact of CTL cells with a saturated incidence function was considered in [12]:

Here H, S, Y, V, and Z represent the densities of uninfected cells, exposed cells, infected cells, free virus, and CTL cells, respectively. Our model uses a more realistic saturated incidence function [10,11]. This saturated incidence functional describes the infection rate taking into consideration the effect of free viruses crowd near the healthy cells. The parameters of the system in Equation (1) are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

The parameters of the mathematical model and their descriptions.

The majority of mathematical models of viral infection ignores the spatial movement of viruses and cells, assuming that the virus and cell populations are well mixed [19]. However, their mobility and a nonuniform spatial distribution can play an important role for the infection development [20]. Thus far, few studies have been devoted to the influence of spatial structure on the dynamics of the virus [21,22]. Reaction–diffusion waves of infection spreading were studied in [23,24,25].

In this work, we consider the previous model in Equation (1) taking into account virus diffusion:

As in (1), , and Z represent the densities of uninfected cells, latently infected cells, infected cells, free virus, and CTLs cells, depending now on the space coordinate location x and on time t, , where is an open bounded set in . The positive constant d is the virus diffusion coefficient. All parameters of the system in Equation (2) have the same biological meanings as in the model in Equation (1). In this paper, we consider the system in Equation (2) with the homogeneous Neumann boundary conditions:

and the initial conditions:

2. Well-Posedness of Model

In this section, we investigate the well-posedness of the model in Equation (2) proving the global existence, the positivity and the boundedness of solutions.

Proposition 1.

For any initial condition satisfying Equations (4)–(5), there exists a unique solution to the problem in Equations (2)–(3) defined on . Moreover, this solution stays non-negative and bounded for all .

Proof.

Let consider the set

where T is a fixed positive constant and , where .

To prove the existence of the solution, we define the following map

such that

where Y is the third component of the solution vector of the following subsystem

with the initial data

Then, the system in Equation (7) can be written abstractly in by the following form

with , , and

It is clear that F is locally Lipschitz in U. Using the theorem of Cauchy–Lipschitz, we deduce that the system in Equation (7) admits a unique local solution on , where . In addition, the system in Equation (7) can be written of the form

It is easy to see that the functions , are continuously differentiable, verifying , , and for all . Since the initial data of the system in Equation (7) are nonnegative, we obtain the positivity of H, S, Y, and Z thanks to the quasi-reversibility principle.

Now, we show the boundedness of solution. Let

Then,

For biological reasons, we assume that the problem initial data are upper-bounded by the carrying capacity. This means that . We deduce that

Thus, H, S, Y, and Z are bounded.

Let us recast the system in Equation (6) as follows

We know that , then from the proposition in [26], we deduce for all the existence and the uniqueness of the solution such that . Furthermore, if , by using the maximum principle relation, we have

We note that is well defined and continuous and is compact, thus admits a fixed point. Then, we conclude the existence of the solution V of (6) and it is positive and bounded. □

Equilibria and Basic Reproduction Number

The system in Equation (2) has an infection-free equilibrium , corresponding to the total absence of viral infection. The basic reproduction number of the system in Equation (2) is given by

with the ratio of exposed cells that will become infected, the average of free virus produced by an infected cell, and the lifespan of the virus. The biological interpretation of represents the rate of secondary infections generated by an infected cell when it is introduced into a population of uninfected cells.

In addition to the disease free equilibrium, our system (Equation (2)) admits three endemic equilibria. The first of them is , where

This endemic steady state is specified as endemic equilibrium without cellular immunity. The second endemic steady state is , where

This endemic steady state is specified as endemic equilibrium with cellular immunity. It is also called interior equilibrium. The third endemic steady state is , where

with .

Noting that , this is not biologically relevant, thus the steady state is not considered. When , the equilibrium exists. We define the reproduction rate of the CTL immune response by

Note that the endemic state exists when . Indeed, if one considers then, in total absence of CTL immune response, the infected cell loaded per unit time is . From the system in Equation (2), we have the CTL cells reproduced due to infected cells stimulating per unit time is . The CTL charge during the lifespan of a CTL cell is . Thus, if , we deduce the existence of .

3. Global Stability

To prove the global stability of the uninfected and the infected steady states, we use the method of construction of Lyapunov functions developed in [12] and can claim the following result

Theorem 1.

The disease-free equilibrium of the model in Equation (2) is globally asymptotically stable when .

Proof.

We define the function by

Then, by using the equations of the system in Equation (2), the time derivative of verifies

Now, we define a Lyapunov function as follows

Calculating the time derivative of along the positive solutions of the model in Equation (2), we obtain

Thus, if implies that . The largest compact invariant is

according to LaSalle’s invariance principle, , the limit system of equations is

For simplicity, we use the same notation,

Since ,

We define another Lyapunov function

then, the time derivative of satisfies

Since the arithmetic mean is greater than or equal to the geometric mean, it follows

therefore and the equality holds if and , which completes the proof. □

Now, we are interested in the stability of the infected steady state . Let us state the following theorem.

Theorem 2.

The infected steady state of the model in Equation (2) is globally asymptotically stable when . In this case, the other infected steady state does not exist.

Proof.

Firstly, we define the function

Using the same technique proposed in [12], we obtain

Now, let us consider the following Lyapunov function

then we deduce

Again, since the arithmetic mean is greater than or equal to the geometric mean, it follows

In addition, when , which means that .

Therefore, by Lyapunov–LaSalle invariance theorem, is globally asymptotically stable when and . □

To prove the stability of equilibrium, let us state the following theorem

Theorem 3.

The infected steady state of the model in Equation (2) is globally asymptotically stable when and . In this case, the other infected steady state is unstable.

Proof.

We consider the following function

Then, we have

As a result, we define a Lyapunov function as follows

then,

since the arithmetic mean is greater than or equal to the geometric mean, it follows

which means that , and the equality hods when , , , , and . By the LaSalle invariance principle, the endemic point is globally stable. □

4. Numerical Simulations

In this section, we present the results of numerical simulations to validate the theoretical results of the previous section. We used the finite difference numerical method with Euler explicit scheme. The convergence of our numerical method was tested by successively decreasing the time and space steps. The values of parameters are given in Appendix A.

We considered the one-dimensional interval and time , where (dimensionless space units) and days. The initial conditions were chosen space dependent to illustrate behavior of spatially inhomogeneous solutions. We used an explicit numerical method with the space step and time step . The program was implemented with Matlab (2014a, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA).

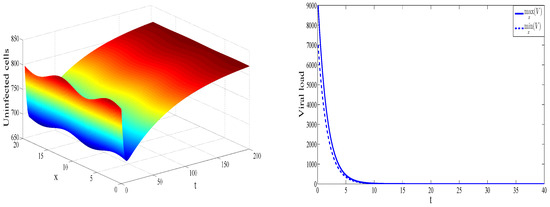

Figure 1 shows spatiotemporal dynamics of uninfected cells (left) and the maximal and the minimal values of the virus concentration in space as a function of time (right). For the values of parameters considered in this example, the basic reproduction number , which implies that the virus-free equilibrium is stable. Therefore, as expected, solution converges toward the equilibrium .

Figure 1.

Dynamics of solution for , , , , , , , , , , and . The concentration of uninfected cells is shown as a function of x and t (left). The maximal and the minimal value of the virus concentration with respect to x are shown as functions of time (right).

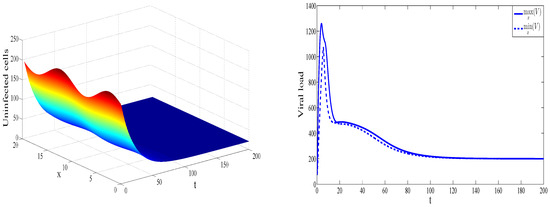

To illustrate convergence to the endemic equilibrium point , we considered the values of parameters presented in Figure 2. In this case, the basic reproduction number is greater than 1, , and the immune reproduction number is less than 1, . Therefore, the free-immune endemic equilibrium is globally stable.

Figure 2.

Dynamics of solution for , , , , , , , , , , and . The concentration of uninfected cells is shown as a function of x and t (left). The maximal and the minimal value of the virus concentration with respect to x are shown as functions of time (right).

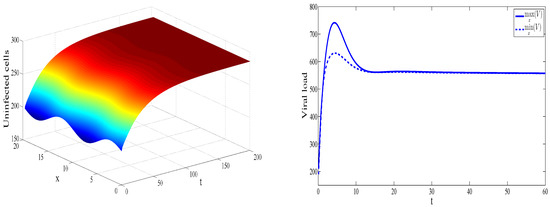

In the case considered in Figure 3, we obtain and . Consequently, we observe that the endemic equilibrium is stable. This, numerical results support the theoretical findings.

Figure 3.

Dynamics of solution for , , , , , , , , , , and . The concentration of uninfected cells is shown as a function of x and t (left). The maximal and the minimal value of the virus concentration with respect to x are shown as functions of time (right).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In this work, we study a model of viral infection in the presence of CTL cells and latently infected cells. We take into consideration not only the variation in time, but also spatial variation of virus distribution and its diffusion, where uninfected cells, latently infected cells, infected cells, and CTL cells do not exhibit any such spatial mobility. As a result, we show the stability of the free-disease equilibrium using the construction of a Lyapunov function when the reproduction number is less than one . If , then two scenarios are established. If , then the equilibrium point is globally asymptotically stable, while, for , the equilibrium point is globally asymptotically stable. We also performed numerical simulations of our model to illustrate behavior of solutions and to confirm the theoretical results. It was established that spatial diffusion of free viruses has no effect on the stability of the steady states. However, the effect appears only for the first days of infection observation.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, grant number PICS 244832.

Acknowledgments

The work was partially supported by the France–Morocco program PICS 244832, “RUDN University Program 5-100” and the French–Russian project PRC2307.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. The Values of Parameters Used in the Numerical Simulations

The values of parameters used in the numerical simulations are given in Table A1:

Table A1.

The values, units and meaning of all used parameters.

Table A1.

The values, units and meaning of all used parameters.

| Parameters | Units | Meaning | Value | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cells L day | Source rate of CD4+ T cells | [27] | ||

| L virion day | Average of infection | [12] | ||

| day | Decay rate of healthy cells | [12] | ||

| day | Death rate of exposed CD4+ T cells | [12] | ||

| day | The rate that exposed cells become infected CD4+ T cells | [12] | ||

| day | Death rate of infected CD4+ T cells, not by CTL killing | [12] | ||

| a | day | The rate of production the virus by infected CD4+ T cells | [12] | |

| day | Clearance rate of virus | [12] | ||

| p | L cell day | Clearance rate of infection | [28] | |

| c | cells cell day | Activation rate CTL cells | [28] | |

| b | day | Death rate of CTL cells | [28] | |

| d | mmday | Diffusion coefficient | – |

References

- Perelson, A.S.; Neumann, A.U.; Markowitz, M.; Leonard, J.M.; Ho, D.D. HIV-1 dynamics in vivo: Virion clearance rate, infected cell life-span, and viral generation time. Science 1996, 271, 1582–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, B.M.; Banks, H.T.; Davidian, M.; Kwon, H.D.; Tran, H.T.; Wynne, S.N.; Rosenberg, E.S. HIV dynamics: Modeling, data analysis, and optimal treatment protocols. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2005, 184, 10–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchell, A.N.; Winer, R.L.; de Sanjosé, S.; Franco, E.L. Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of genital HPV infection. Vaccine 2006, 24, S52–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbasha, E.H.; Dasbach, E.J.; Insinga, R.P. A multi-type HPV transmission model. Bull. Math. Biol. 2008, 70, 2126–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Zu, J. The review of differential equation models of HBV infection dynamics. J. Virol. Methods 2019, 266, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskaf, A.; Allali, K.; Tabit, Y. Optimal control of a delayed hepatitis B viral infection model with cytotoxic T-lymphocyte and antibody responses. Int. J. Dyn. Control. 2017, 5, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodarz, D. Hepatitis C virus dynamics and pathology: The role of CTL and antibody responses. J. Gen. Virol. 2003, 84, 1743–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layden, J.E.; Layden, T.J. How can mathematics help us understand HCV? Gastroenterology 2001, 120, 1546–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.A.; Bangham, C.R.M. Population dynamics of immune responses to persistent viruses. Science 1996, 272, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Min, L.; Kuang, Y. Global stability of infection-free state and endemic infection state of a modified human immunodeficiency virus infection model. IET Syst. Biol. 2015, 9, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Min, L. Dynamics Analysis and Simulation of a Modified HIV Infection Model with a Saturated Infection Rate. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allali, K.; Danane, J.; Kuang, Y. Global Analysis for an HIV Infection Model with CTL Immune Response and Infected Cells in Eclipse Phase. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.L.; De Leenheer, P. Virus dynamics: A global analysis. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2003, 63, 1313–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daar, E.S.; Moudgil, T.; Meyer, R.D.; Ho, D.D. Transient highlevels of viremia in patients with primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, J.O.; Walker, B.D. Acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocharov, G.; Volpert, V.; Ludewig, B.; Meyerhans, A. Mathematical Immunology of Virus Infections; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, G.R.; Cunningham, P.; Kelleher, A.D.; Zauders, J.; Carr, A.; Vizzard, J.; Law, M.; Cooper, D.A. The Sydney Primary HIV Infection Study Group. Patterns of viral dynamics during primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 1998, 178, 1812–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacker, T.; Collier, A.; Hughes, J.; Shea, T.; Corey, L. Clinical and epidemiologic features of primary HIV infection. Ann. Int. Med. 1996, 125, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, N.F. Essential Mathematical Biology; Springer: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Grebennikov, D.; Bouchnita, A.; Volpert, V.; Bessonov, N.; Meyerhans, A.; Bocharov, G. Spatial lymphocyte dynamics in lymph nodes predicts the CTL frequency needed for HIV infection control. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziane, M.; Hattaf, K.; Yousfi, N. Dynamics of a class of HIV infection models with cure of infected cells in eclipse stage. Acta Biotheor. 2015, 63, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattaf, K.; Yousfi, N. A numerical method for delayed partial differential equations describing infectious diseases. Comput. Math. Appl. 2016, 72, 2741–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofimchuk, S.; Volpert, V. Traveling waves for a bistable reaction-diffusion equation with delay. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 2018, 50, 1175–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocharov, G.; Meyerhans, A.; Bessonov, N.; Trofimchuk, S.; Volpert, V. Interplay between reaction and diffusion processes in governing the dynamics of virus infections. J. Theor. Biol. 2018, 457, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessonov, N.; Bocharov, G.; Touaoula, T.M.; Trofimchuk, S.; Volpert, V. Delay reaction-diffusion equation for infection dynamics. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst.-B 2019, 24, 2073–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudon, T.; Lagoutiere, F.; Tine, L.M. The Lifschitz-Slyozov equation with space-diffusion of monomers. Kinet. Relat. Model. 2012, 5, 325–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, J.; Heffernan, J. Oscillatory viral dynamics in a delayed HIV pathogenesis model. Math. Biosci. 2009, 219, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Luo, Y.; Chen, M. Stability and Hopf bifurcation of a HIV infection model with CTL-response delay. Comput. Math. Appl. 2011, 62, 3091–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).