Abstract

Fullerenes are molecules that can be presented in the form of cage-like polyhedra, consisting only of carbon atoms. Fullerene graphs are mathematical models of fullerene molecules. The transmission of a vertex v of a graph is a local graph invariant defined as the sum of distances from v to all the other vertices. The number of different vertex transmissions is called the Wiener complexity of a graph. Some calculation results on the Wiener complexity and the Wiener index of fullerene graphs of order and IPR fullerene graphs of order are presented. The structure of graphs with the maximal Wiener complexity or the maximal Wiener index is discussed, and formulas for the Wiener index of several families of graphs are obtained.

1. Introduction

A fullerene is a spherically shaped molecule consisting of carbon atoms in which every carbon ring forms a pentagon or a hexagon. Every atom of a fullerene has bonds with exactly three neighboring atoms. The molecule may be a hollow sphere, ellipsoid, tube, or many other shapes and sizes. Fullerenes are the subject of intense research in chemistry, and they have found promising technological applications, especially in nanotechnology and materials science [1,2].

Molecular graphs of fullerenes are called fullerene graphs. A fullerene graph is a 3-connected planar graph in which every vertex has degree 3, and every face has size 5 or 6. By Euler’s polyhedral formula, the number of pentagonal faces is always 12. It is known that fullerene graphs having n vertices exist for all even and for . The number of all non-isomorphic fullerene graphs can be found in [3,4,5]. The set of fullerene graphs with n vertices will be denoted as . The number of faces of graphs in is and, therefore, the number of hexagonal faces is . Despite the fact that the number of pentagonal faces is very small compared to the number of hexagonal faces, their location is crucial to the shape and properties of fullerene molecules. Fullerene graphs without adjacent pentagons, i.e., each pentagon is surrounded only by hexagons, satisfy the isolated pentagon rule (IPR), and are called IPR fullerene graphs. They are considered as molecular graphs of thermodynamic stable fullerene compounds. The number of all non-isomorphic IPR fullerene graphs was reported, for example, in [5,6]. Mathematical studies of fullerenes include applications of topological and graph theory methods, information theory approaches, design of combinatorial and computational algorithms, etc. (see selected articles [3,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]). A comprehensive bibliography on mathematical methods and its applications can be found in [1,2,4,12,28,29]. The set of IPR fullerene graphs with n vertices will be denoted as .

The vertex set of a graph G is denoted by . The number of vertices of G is called its order. The distance between vertices is the number of edges in a shortest path connecting u and v in G. The maximal distance between vertices of a graph G is called the diameter of G. Vertices are diametrical if the distance between them is equal to the diameter of a graph. By transmission of , we mean the sum of distances from vertex v to all the other vertices of G, . Transmissions of vertices are used for the design of many distance-based topological indices [30]. Usually, a topological index is a graph invariant that maps a family of graphs to a set of numbers such that values of the invariant coincide for isomorphic graphs. The Wiener index is a topological index defined as a half of the sum of vertex transmissions:

It was introduced as a structural descriptor for tree-like organic molecules by Harold Wiener [31]. The definition of the index in terms of distances between vertices of a graph was given by Haruo Hosoya [32]. The Wiener index that has found important applications in chemistry (see books and reviews [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]). Various aspects of the theory and practice of the Wiener index of fullerene graphs are discussed in many works [7,8,11,12,13,15,16,17,18,19,20,22,24,42].

The number of different vertex transmissions in a graph G is known as the Wiener complexity [43] (or the Wiener dimension [7]), . This graph invariant can be regarded as a measure of transmission variety. A graph is called transmission irregular if all vertices of the graph have pairwise different transmissions, i.e., it has the largest possible Wiener complexity. It is obvious that a transmission irregular graph has the identity automorphism group. Various properties of transmission irregular graphs were studied in [43,44,45]. It was shown that almost all graphs are not transmission irregular. Several infinite families of transmission irregular graphs were constructed for trees, 2-connected graphs, and 3-connected cubic graphs in [44,46,47,48,49].

In this paper, we present some results of studies of the Wiener complexity and the Wiener index of fullerene graphs. In particular, we are interested in two questions: does a transmission irregular fullerene graph exist and can a graph with the maximal Wiener complexity has the maximal Wiener index?

2. Wiener Complexity of Fullerene Graphs

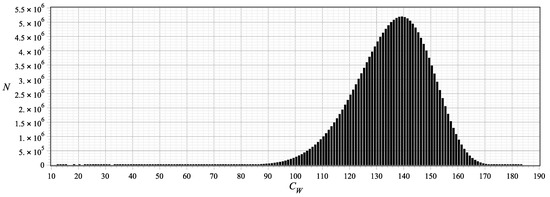

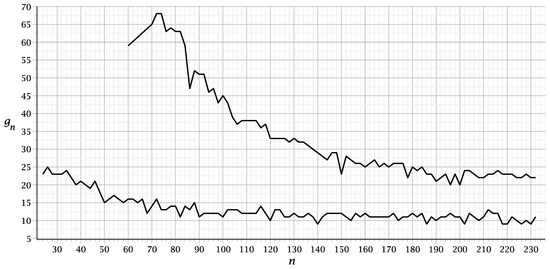

The Wiener complexity of fullerene graphs was examined for fullerene and IPR-fullerene graphs with and vertices, respectively. A typical distribution of the numbers of fullerene graphs with fixed number of vertices with respect to values of is shown in Figure 1. The number of graphs of (100 faces) is 177,175,687. Denote by the maximal Wiener complexity among all fullerene graphs with n vertices, i.e., , where or . Let be a difference between order and the Wiener complexity, . If a transmission irregular graph exists, then . It is obvious that a transmission irregular graph has the identity automorphism group. The behavior of when the number of vertices n increases is shown in Figure 2. The bottom and top lines correspond to all fullerene graphs and to IPR fullerene graphs, respectively. Explicit values of can be found in Table 1 and Table 2.

Figure 1.

Distribution of fullerene graphs of with respect to their Wiener complexity (N is the number of graphs).

Figure 2.

Difference between order and the maximal Wiener complexity of fullerene graphs (bottom line) and IPR fullerene graphs (top line) of order .

Table 1.

Maximal Wiener complexity and Wiener indices of fullerene graphs.

Table 2.

Maximal Wiener complexity and Wiener indices of IPR fullerene graphs.

Proposition 1.

There do not exist transmission irregular fullerene graphs with vertices and IPR fullerene graphs with vertices.

Since the almost all fullerene graphs have no symmetries, we believe that transmission irregular graphs exist for a large number of vertices (when the interval of possible values of transmissions will be sufficiently large with respect to the number of vertices).

Problem 1.

Does there exist a transmission irregular fullerene graph (IPR fullerene graph)? If yes, then what is the smallest order of such graphs?

3. Graphs with the Maximal Wiener Complexity

In this section, we study the following problem: can the Wiener index of a fullerene graph with the maximal Wiener complexity be maximal? Denote by the maximal Wiener index among all fullerene graphs with n vertices, i.e., , where or .

Numerical data for the Wiener indices of fullerene graphs in Table 1 and Table 2 show that Wiener indices of graphs with maximal are not maximal. Here, three columns , W, and D contain the maximal Wiener complexity, the Wiener index, and the diameter of graphs with , respectively. Three columns , , and D contain the maximal Wiener index of graphs with n vertices, the Wiener complexity, and the diameter of graphs with . Based on data of the tables, one can make the following observations for the corresponding graphs:

- Values of the maximal Wiener complexity of all fullerene graphs do not decrease except for one case: and . For IPR fullerene graphs, we have four exceptions (see pairs ; ; , and ).

- Wiener indices of fullerene and IPR fullerene graphs with maximal () are not maximal except graphs of order with ().

- Several fullerene or IPR fullerene graphs of fixed n may have the maximal complexity .

- Almost all fullerene graphs with fixed have distinct Wiener indices except for two graphs of order 46 with and and two IPR fullerene graphs of order 204 with and 185,306.

- Given n, only one fullerene graph has the maximal Wiener index while there are pairs of IPR fullerene graphs with the same maximal W (see graphs of order 132, 186, 204, 222, and 258).

- The diameter D of graphs with fixed is less than or equal to the diameter of graphs with a maximal Wiener index for all fullerene graphs (with seven exceptions for IPR fullerene graphs of order 90, 92, 96, 100, 102, 116, and 124).

- Fullerene graphs with the maximal Wiener index have the maximal diameter among all fullerenes. The values of the Wiener complexity of these graphs can vary greatly. This can be partially explained by the appearance of symmetries in graphs with .

It is of interest how the pentagons are distributed among hexagons for fullerene graphs of with the maximal Wiener complexity , . Does there exist any regularity in the distribution of pentagons? Table 3 gives some information on the occurrence of pentagonal parts of a particular size in these graphs (an isolated pentagon forms a part). Here, N is the number of graphs in which pentagons form isolated connected parts. The considered fullerene graphs contain at most eight isolated parts.

Table 3.

The number of graphs with isolated pentagonal parts.

Table 4 shows how many fullerene graphs with the maximal Wiener complexity have isolated pentagons. Here, N is the number of graphs having isolated pentagons. These fullerene graphs contain at most five isolated pentagons.

Table 4.

The number graphs with isolated pentagons.

Does there exist an IPR fullerene graph with maximal Wiener complexity (lines of Figure 2 will have an intersection for )? We believe that the answer to this question will be positive for sufficiently large n.

4. Fullerene Graphs with the Maximal Wiener Index

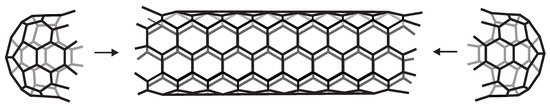

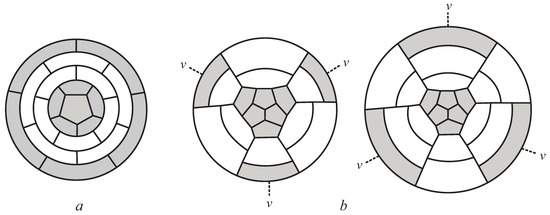

The Wiener index of fullerene graphs was studied in [7,8,12,13,15,16,17,18,19,20,42]. A class of fullerene graphs of tubular shapes is called nanotubical fullerene graphs. They have cylindrical shape with the two ends capped by subgraphs containing six pentagons and possibly some hexagons called caps (see an illustration in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Construction of a nanotubical fullerene graph with two caps.

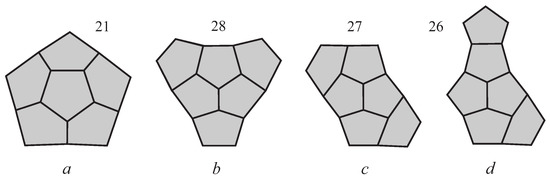

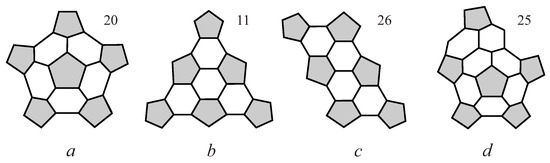

Consider fullerene graphs with the maximal Wiener indices (see Table 1). Five graphs of – and contain one pentagonal part and the other 102 graphs possess two pentagonal parts. Two pentagonal parts of every fullerene graph are the same and contain diametrical vertices. Therefore, such graphs are nanotubical fullerene graphs with caps containing identical pentagonal parts. All diagrams of the parts are depicted in Figure 4. Cap of types a–c have symmetries. The number of fullerene graphs having a given part is shown near diagrams.

Figure 4.

Pentagonal parts of caps for nanotubical fullerene graphs with the maximal Wiener index.

Characteristics of the corresponding nanotubes are reported in [9]. We assume that a type of a cap is determined by the type of its pentagonal part. Types of caps of fullerene graphs are presented in column t of Table 1. Constructive approaches for enumeration of various caps were proposed in [25,26]. Consider every kind of cap type.

1. Type a. Caps of type a define (5,0)-nanotubical fullerene graphs. The structure of graphs of this infinite family is clear from an example in Figure 5a. Analytical formulas for diameter and the Wiener index of such fullerene graphs were obtained in [7,18]. To indicate the order of graph G, we will use notation . We rewrite the formulas in terms of n.

Figure 5.

Structure of fullerene graphs with caps of types (a) and (b).

Proposition 2

([7,18]). Let be a nanotubical fullerene graph with caps of type a. It has vertices, . Then, , , and , , , and for ,

Based on numerical data of Table 1, the similar results have been obtained for fullerene graphs of order with caps of the other three types.

2. Type b. Caps of type b define (3,3)-nanotubical fullerene graphs. The structure of graphs of the corresponding family is clear from examples of Figure 5b. Vertices marked by v should be identified in every graph. Table 1 contains 28 such graphs.

Proposition 3.

Let be a nanotubical fullerene graph with caps of type b. It has vertices, . Then, , , and for ,

Two caps of type b have adjacent pentagonal rings only for . If fullerene graphs with caps of types a and b have the same number of vertices (), then the graph with caps of type a has the maximal Wiener index.

3. Type c. Caps of type c define (4,2)-nanotubical fullerene graphs. Fullerene graphs with caps of type c will be splitted into two disjoint families, . The corresponding graphs are marked in column t of Table 1 by (14 graphs) and (13 graphs). The numbers of vertices of graphs of and are given in Table 5. The orders of graphs of do not coincide with the orders of graphs from the set . By analysis of 3D-models of fullerene graphs, it is possible to determine the mutual position of their pentagonal parts. As an example, fragments of graphs with (case ) and (case ) vertices are depicted in Figure 6.

Table 5.

Parameters of fullerene graphs with vertices and caps of types c and d ().

Figure 6.

Mutual position of pentagonal parts for caps of types c and d.

Proposition 4.

- (a)

- Let be a nanotubical fullerene graph of family . Then, for ,

- (b)

- Let be a nanotubical fullerene graph of family . Then, for ,

The Wiener complexity and the diameter of are shown in Table 5.

4. Type d. Caps of type d define (5,1)-nanotubical fullerene graphs. Such graphs will be also splitted into two disjoint families, . The both families have 13 members (see graphs with marks and in column t of Table 1). The numbers of vertices of graphs of and are shown in Table 5. The orders of graphs of do not coincide with the orders of graphs from the set . An example of the mutual position of pentagonal parts of graphs from these families with and vertices are shown in Figure 6.

Proposition 5.

- (a)

- Let be a nanotubical fullerene graph of family . Then, and for ,

- (b)

- Let be a nanotubical fullerene graph of family . Then, and for ,

The Wiener complexity and the diameter of are shown in Table 5.

The above considerations of fullerene graphs with vertices lead to the following conjectures for all fullerene graphs.

Conjecture 1.

If a fullerene graph of an arbitrary sufficiently large order has the maximal Wiener index, then it is a nanotubical fullerene graph with caps of types a–d and its Wiener index is given by Propositions 2–5.

Conjecture 2.

The Wiener complexity and the diameter of fullerene graphs of an arbitrary sufficiently large order having the maximal Wiener index are given in Propositions 2–5.

5. IPR Fullerene Graphs with the Maximal Wiener Index

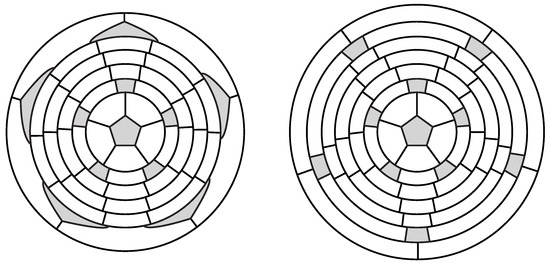

Numerical data for the Wiener indices of IPR fullerene graphs of order are presented in Table 2. The structure of the table is the same as for fullerene graphs. Graphs with maximal Wiener index (column ) are nanotubical fullerene graphs with two identical caps. All caps are defined by four fragments shown in Figure 7. Caps of type a–c have no symmetries. The number of fullerene graphs having a given cap is shown near diagrams. Note that it is difficult to separate caps from each other when IPR fullerene graphs have a shape close to spherical one. Therefore, caps of types can be recognized only for fullerene graphs of a sufficiently large number of vertices when graphs became nanotubical. A type of cap is indicated in column t of Table 2. Consider graphs with these caps.

Figure 7.

Pentagonal parts of caps in nanotubical IPR fullerene graphs with the maximal Wiener index.

1. Type a. Caps of type a define (5,5)-nanotubical fullerene graphs. Caps of this type can be positioned relative to each other in two ways. The structure of the corresponding graphs of this infinite families is described by examples in Figure 8. Analytical formulas for the Wiener index of these graphs are presented in [17]. We rewrite the formulas in terms of n.

Figure 8.

IPR fullerene graphs (left) and (right) with caps of type a.

Proposition 6

([17]).

(a) Let be a nanotubical IPR fullerene graph of family . It has vertices, and k is odd. Then, , , and

(b) Let be a nanotubical IPR fullerene graph of family . It has vertices, and k is even. Then, , , and

2. Type b. Caps of type b define (9,0)-nanotubical fullerene graphs. The caps can be positioned relative to each other in four ways as shown in Figure 9. Since graphs with fragments of cases and almost always have the same Wiener index, we split graphs into two infinite families. Graphs having structures and form family and , respectively. Each family contains two graphs with the same maximal Wiener index for fixed n. Table 6 shows the number of vertices of the families. The difference between n of the neighboring graphs is 36. The numbers in table’s sells are the number of hexagonal rings (k) in the fragments connecting two caps (see Figure 9). The graph of order 168 with caps of type has almost maximal Wiener index, 116,097, while the maximal Wiener index is 116,100. Remember that the graph of order 150 with the maximal Wiener index, 87,335, has caps of type a. The graph of order 150 with caps of type has the second maximal Wiener index, 86,379, and the graph of type has the third maximal Wiener index, 86,373. The graphs of order 240 with caps of types and have the second maximal Wiener index, 302,034 (the graph with the caps of type a gives maximum W).

Figure 9.

Mutual positions of caps of type b in IPR fullerene graphs.

Table 6.

IPR fullerene graphs with caps of type b.

Proposition 7.

- (a)

- Let be a nanotubical IPR fullerene graph of family . It has vertices, . Then, and

- (b)

- Let be a nanotubical IPR fullerene graph of family . It has vertices, . Then, and

3. Types c and d. Caps of types c and d generate many cases of their mutual arrangement. By analyzing the structure of fullerene graphs, we have preliminarily identified several families. The number of vertices of eight families of graphs with the caps of type c can be written as , , where . For nine families of graphs with the caps of type d, we have , , where .

Conjecture 3.

If an IPR fullerene graph of an arbitrary sufficiently large order has the maximal Wiener index, then it is a nanotubical fullerene graph with caps of types a–d and its Wiener index is given by Propositions 6 and 7 for graphs of types a and b.

6. Conclusions

Problems of finding fullerene graphs with the maximal Wiener complexity and Wiener index are studied. Numerical data show that graphs with the maximal Wiener complexity may exist for quite a large number of vertices. Some basic properties of fullerene graphs having the maximal Wiener index are established. We hope that the presented considerations will stimulate further study of the extremal fullerene graphs with respect to the Wiener index.

It is worth noting that, according to experimental studies, it was observed that there are no theoretically well founded correlations between the Wiener index and the predicted energetic stability of fullerene isomers in some cases [11,22]. In order to improve the prediction accuracy, Ori et al. defined a topological efficiency index derived from the Wiener index [24].

Author Contributions

Methodology, A.Y.V.; Software, A.A.D.

Funding

This work was supported by the Laboratory of Topology and Dynamics, Novosibirsk State University (Contract no. 14.Y26.31.0025 with the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ashrafi, A.R.; Diudea, M.V. Distance, Symmetry, and Topology in Carbon Nanomaterials; Carbon Materials: Chemistry and Physics Book 9; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo, F.; Graovac, A.; Ori, O. The Mathematics and Topology of Fullerenes; Carbon Materials: Chemistry and Physics Book 4; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann, G.; Dress, A.W.M. A constructive enumeration of fullerenes. J. Algorithams 1997, 309, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.W.; Manolopoulos, D.E. An Atlas of Fullerenes; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Goedgebeur, J.; McKay, B.D. Recursive generation of IPR fullerenes. J. Math. Chem. 2015, 53, 1702–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedgebeur, J.; McKay, B.D. Fullerenes with distant pentagons. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2015, 74, 659–672. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, Y.; Andova, V.; Klavžar, S.; Škrekovski, R. Wiener dimension: Fundamental properties and (5,0)-nanotubical fullerenes. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2014, 72, 279–294. [Google Scholar]

- Andova, V.; Orlić, D.; Škrekovski, R. Leapfrog fullerenes and Wiener index. Appl. Math. Comput. 2017, 309, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bašić, N.; Brinkmann, G.; Fowler, P.W.; Pisanski, T.; Van Cleemput, N. Sizes of pentagonal clusters in fullerenes. J. Math. Chem. 2017, 55, 1669–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erokhovets, N. Construction of fullerenes and Pogorelov polytopes with 5-, 6- and one 7-gonal face. Symmetry 2018, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.W. Resistance distances in fullerene graphs. Croat. Chem. Acta 2002, 10, 401–408. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, P.W.; Caporossi, G.; Hansen, P. Distance matrices, Wiener indices, and related invariants of fullerenes. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2001, 105, 6232–6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M. Computing Wiener index of C24n fullerenes. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 2015, 12, 1847–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Dehmer, M.; Rajabi-Parsa, M.; Mowshowitz, A.; Emmert-Streib, F. On properties of distance-based entropies on fullerene graphs. Entropy 2019, 12, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Ghorbani, T. Computing the Wiener index of an infinite class of fullerenes. Studia Ubb Chemia 2013, 58, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani, M.; Songhori, M. Computing Wiener index of C12n fullerenes. Ars Combinatoria 2017, 130, 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, T.; Mondal, S.; Mondal, S.; Mandal, B. Distance numbers and Wiener indices of IPR fullerenes with formula C10(n−2) (n ≥ 8) in analytical forms. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2018, 701, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graovac, A.; Ori, O.; Faghani, M.; Ashrafi, A. Distance property of fullerenes. Iranian J. Math. Chem. 2011, 2, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, H.; Faghani, M.; Ashrafi, A. The Wiener and Wiener polarity indices of a class of fullerenes with exactly 12n carbon atoms. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2014, 71, 361–372. [Google Scholar]

- Iranmanesh, A.; Alizadeh, Y.; Mirzaie, S. Computing Wiener polynomial, Wiener index and hyper Wiener index of C80 fullerene by GAP program. Fuller. Nanotub. Car. Nanostruct. 2009, 17, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ori, O.; D’Mello, M. A topological study of the structure of the C76 fullerene. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1992, 197, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabirov, D.S.; Ori, O.; László, I. Isomers of the C84 fullerene: A theoretical consideration within energetic, structural, and topological approaches. Fuller. Nanotub. Carbon Nanostruct. 2018, 26, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabirov, D.S.; Ōsawa, E. Information entropy of fullerenes. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 1576–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukičević, D.; Cataldo, F.; Ori, O.; Craovac, A. Topological efficiency of C66 fullerene. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2011, 501, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, G.; Nathusius, U.; Palser, A.H.R. A constructive enumeration of nanotube caps. Discrete Appl. Math. 2002, 116, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, G.; Fowler, P.W.; Manolopoulos, D.E.; Palser, A.H.R. A census of nanotube caps. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999, 315, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchstaber, V.M.; Erokhovets, N.Y. Finite sets of operations sufficient to construct any fullerene from C20. Struct. Chem. 2017, 28, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andova, V.; Kardoš, F.; Škrekovski, R. Mathematical aspects of fullerenes. Ars Math. Contemp. 2016, 11, 353–379. [Google Scholar]

- Schwerdtfeger, P.; Wirz, L.N.; Avery, J. The topology of fullerenes. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2015, 5, 96–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafdini, R.; Reti, T. On the transmission-based graph topological indices. Kragujevac J. Math. 2020, 44, 41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener, H. Structural determination of paraffin boiling points. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1947, 69, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoya, H. Topological index. A newly proposed quantity characterizing the topological nature of structural isomers of saturated hydrocarbons. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1971, 4, 2332–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehmer, M.; Emmert-Streib, F. Quantitative Graph Theory: Mathematical Foundations and Applications; Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications; Chapman and Hall/CRC: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrynin, A.A.; Entringer, R.; Gutman, I. Wiener index for trees: Theory and applications. Acta Appl. Math. 2001, 340, 211–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrynin, A.A.; Gutman, I.; Klavžar, S.; Žigert, P. Wiener index of hexagonal systems. Acta Appl. Math. 2002, 72, 247–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, I.; Furtula, B. Distance in Molecular Graphs—Theory; Mathematical Chemistry Monographs, 12; University of Kragujevac: Kragujevac, Serbia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman, I.; Furtula, B. Distance in Molecular Graphs—Applications; Mathematical Chemistry Monographs, 13; University of Kragujevac: Kragujevac, Serbia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman, I.; Polansky, O.E. Mathematical Concepts in Organic Chemistry; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Todeschini, R.; Consonni, V. Handbook of Molecular Descriptors; Wiley–VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Trinajstić, N. Chemical Graph Theory, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Knor, M.; Škrekovski, R.; Tepeh, A. Mathematical aspects of Wiener index. Ars Mathematica Contemporanea 2016, 11, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, A.R. Wiener index of nanotubes, toroidal fullerenes and nanostars. In The Mathematics and Topology of Fullerenes; Cataldo, F., Graovac, A., Ori, O., Eds.; Carbon Materials: Chemistry and Physics Book 4; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, Y.; Klavžar, S. Complexity of topological indices: The case of connective eccentric index. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2016, 76, 659–667. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, Y.; Klavžar, S. On graphs whose Wiener complexity equals their order and on Wiener index of asymmetric graphs. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018, 328, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klavžar, S.; Jemilet, D.A.; Rajasingh, I.; Manuel, P.; Parthiban, N. General transmission lemma and Wiener complexity of triangular grids. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018, 338, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrynin, A.A. On 2-connected transmission irregular graphs. J. Appl. Ind. Math. 2018, 28, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrynin, A.A. Infinite family of 2-connected transmission irregular graphs. Appl. Math. Comput. 2019, 340, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrynin, A.A. Infinite family of transmission irregular trees of even order. Discrete Math. 2019, 340, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrynin, A.A. Infinite family of 3-connected cubic transmission irregular graphs. Discrete Appl. Math. 2019, 340, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).