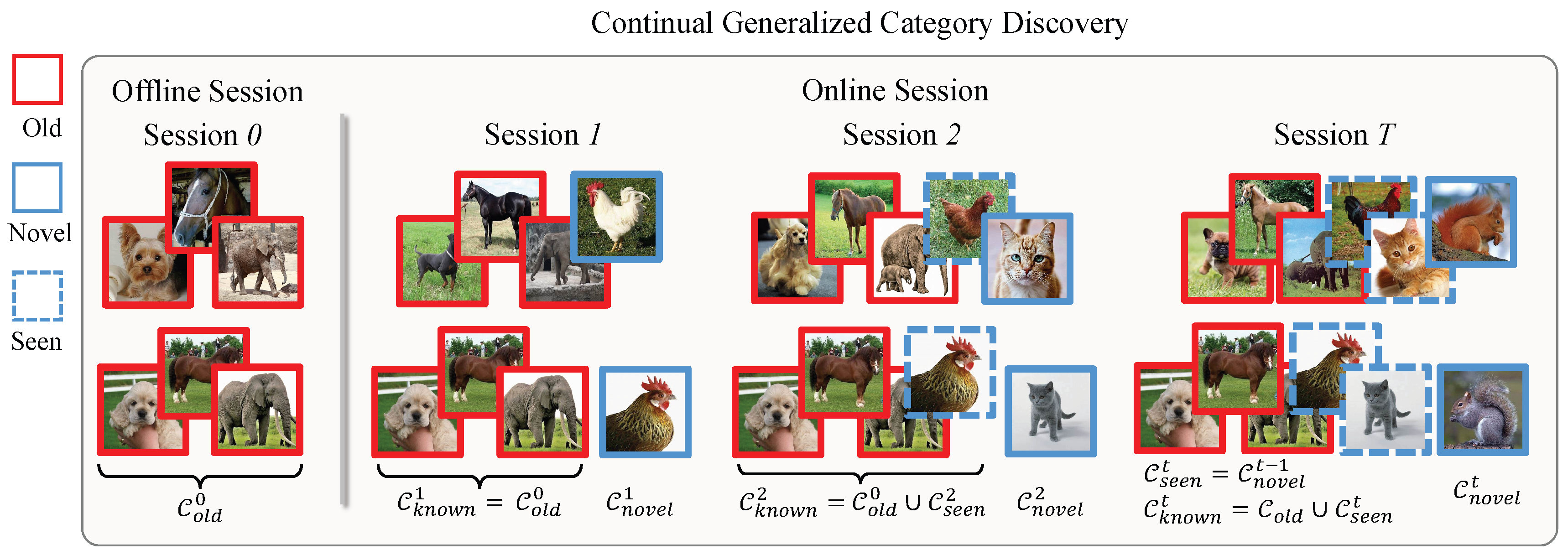

4.2. Evaluation Protocol

At each session, after training, the model is evaluated on a disjoint test set

containing samples from both

and

. Following standard practice, we compute clustering accuracy (ACC) using the Hungarian algorithm [

39] to find the optimal assignment between predicted cluster labels

and ground-truth labels

:

where

and

p denotes the optimal permutation. We report accuracy across three subsets: “All” (all classes

), “Known” (previously learned classes

), and “Novel” (newly discovered classes

).

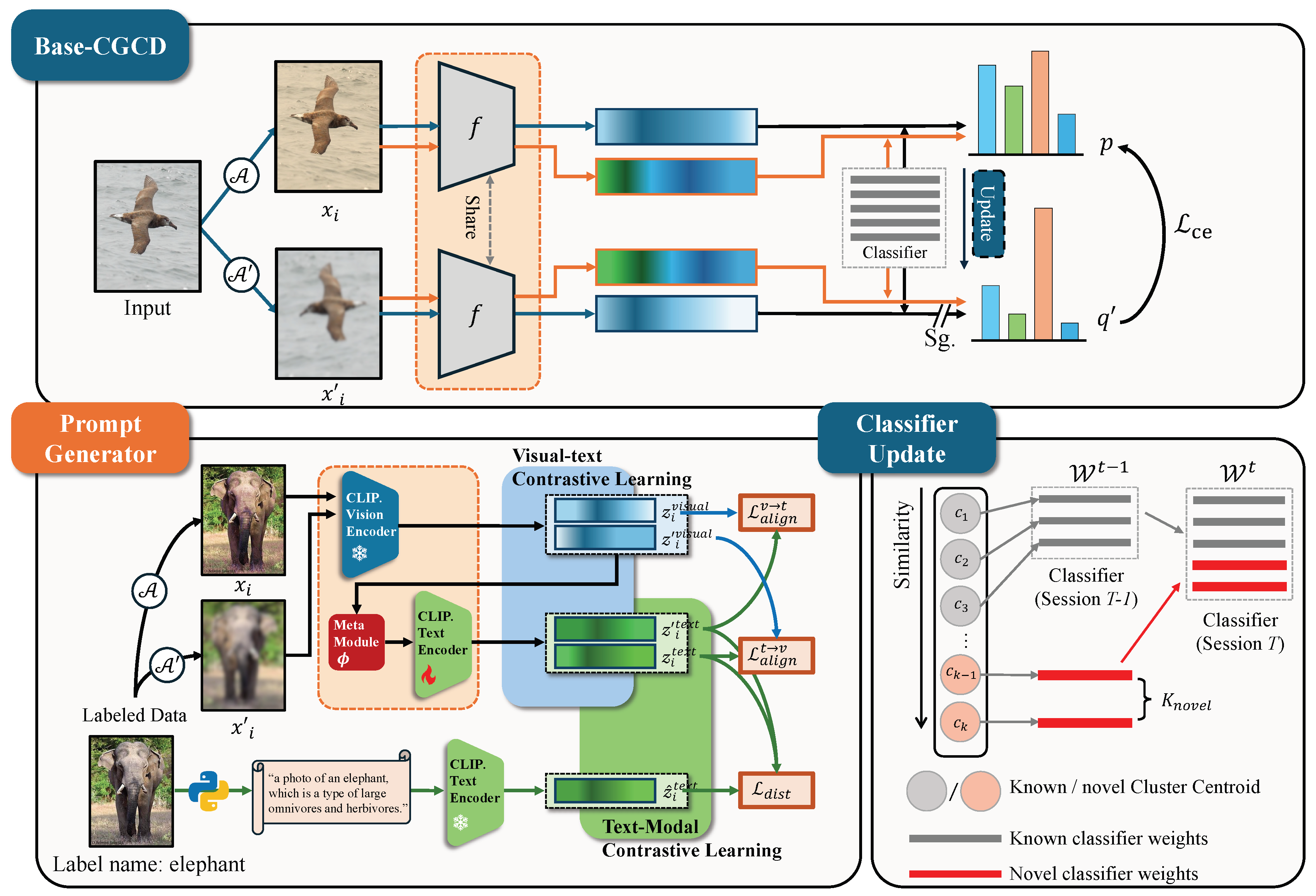

Implementation

In all experiments, we employ ViT-B/16 pretrained with DINO v1 [

13] as the initial backbone and fine-tune only the last transformer block. Our training proceeds in two stages:

Stage 1: Prompt Generation Network Training. During the offline session (Session 0), we train the prompt generation network on all labeled data for 100 epochs. In this stage, we freeze the CLIP vision encoder and fine-tune only the last layer of the CLIP text encoder. This allows the meta-module to learn effective mappings from visual features to textual representations while preserving the pretrained vision-language alignment.

Stage 2: Continual Discovery with Dual-Modal Learning. After training, we replace the DINO backbone in Base-CGCD with the trained prompt generation network and CLIP encoders. At each online session (Sessions 1 to T), we train on the unlabeled data containing both known and novel classes for 30 epochs with a batch size of 128 and a learning rate of 0.1. During this stage, we freeze the text encoder and fine-tune the vision encoder to adapt visual representations while maintaining stable textual features.

The Base-CGCD baseline follows the hyperparameter settings from [

7,

16]. All experiments are conducted on NVIDIA RTX A800 GPUs.

4.3. Results

4.3.1. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

We compare DMCL against Base-CGCD and recent state-of-the-art C-GCD methods including GCD [

3], SimGCD [

16], GM [

12], MetaGCD [

40], PromptCCD [

6], and Happy [

7].

Table 2 presents comprehensive results across four datasets with three online sessions. DMCL achieves competitive or superior performance across all baselines in most scenarios.

Novel Class Discovery. DMCL demonstrates strong plasticity in discovering novel classes. On CIFAR-100, DMCL achieves 67.00% novel class accuracy at Session 3, substantially outperforming Happy at 63.80% and PromptCCD at 55.12%. On ImageNet-100, DMCL attains 74.32% at Session 3, surpassing Happy at 73.24% and significantly ahead of other methods. Notably, on CUB, DMCL achieves remarkable improvements, reaching 77.82%, 79.34%, and 48.00% novel class accuracy across three sessions, compared to Happy’s results of 65.03%, 64.22%, and 40.16%. These results demonstrate that dual-modal contrastive learning effectively enriches representations and enhances discriminability for novel category discovery.

Knowledge Retention. For previously learned classes, DMCL maintains competitive accuracy while balancing plasticity. On CIFAR-100, DMCL achieves 87.08% and 78.79% known class accuracy at Sessions 1 and 2, outperforming most baselines. On ImageNet-100, DMCL attains 86.14% and 82.72% at Sessions 1 and 2, comparable to Happy’s 84.52% and 82.61%. This validates that our approach effectively mitigates catastrophic forgetting through adaptive fusion of visual and textual modalities.

Fine-Grained Recognition. On the challenging fine-grained CUB dataset, DMCL substantially outperforms all methods across sessions. At Sessions 1 and 2, DMCL achieves overall accuracies of 82.93% and 77.98%, surpassing Happy’s 82.03% and 75.24% and significantly ahead of other methods. This highlights the benefit of incorporating textual semantics for fine-grained visual discrimination, where subtle inter-class differences require richer multimodal representations.

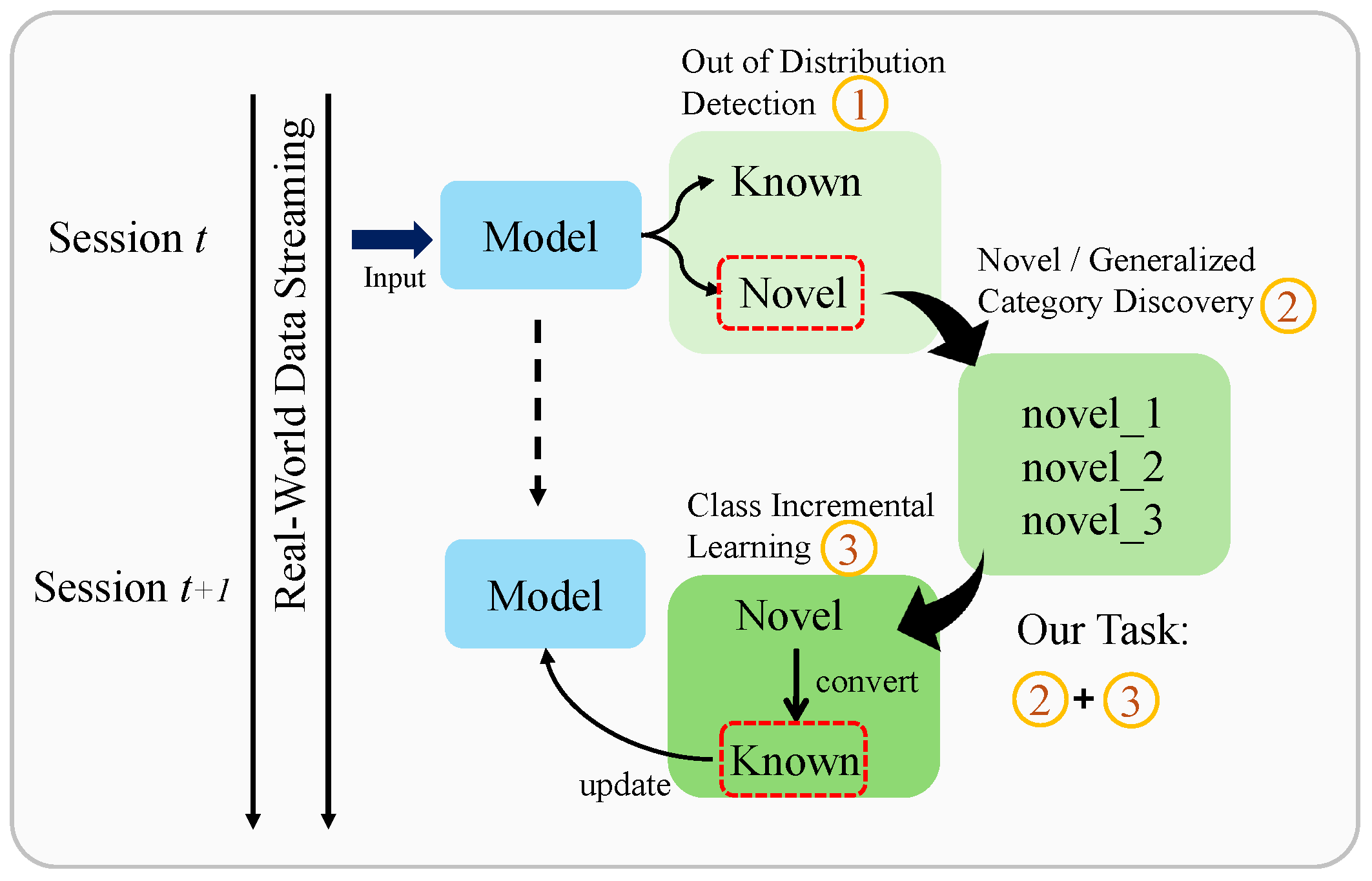

4.3.2. Forgetting and Discovery Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate the model’s discovery capability and resistance to catastrophic forgetting, we analyze two key metrics: the maximum forgetting rate and the final discovery rate . The metric measures the capability to maintain performance on old categories, where lower values indicate better retention. The metric measures the ability to discover novel categories, where higher values indicate better discovery performance.

Both metrics are accuracy-based. The clustering accuracy on old categories

and novel categories

at session

t can be computed as follows:

where

and

denote the number of old and novel category samples from

, and

and

denote the ground-truth labels of old and novel samples, respectively. The forgetting and discovery metrics are then defined as

and

.

Table 3 presents the forgetting and discovery analysis on CUB. Compared to the state-of-the-art method Happy, DMCL demonstrates substantial improvements on both metrics. Specifically, DMCL reduces the forgetting rate

from 4.18% to 3.79%, achieving the lowest forgetting among all methods. Meanwhile, DMCL significantly improves the discovery rate

from 53.79% to 71.05%, demonstrating enhanced plasticity for novel class learning. In terms of overall performance, DMCL attains an average accuracy of 77.90%, surpassing Happy at 77.88% and PromptCCD at 55.45%.

These results validate that dual-modal contrastive learning with adaptive fusion effectively addresses the plasticity–stability dilemma in continual category discovery. The superior performance on the fine-grained CUB dataset particularly highlights the benefit of incorporating textual semantics, where subtle inter-class differences require richer multimodal representations to maintain discriminative decision boundaries across sessions.

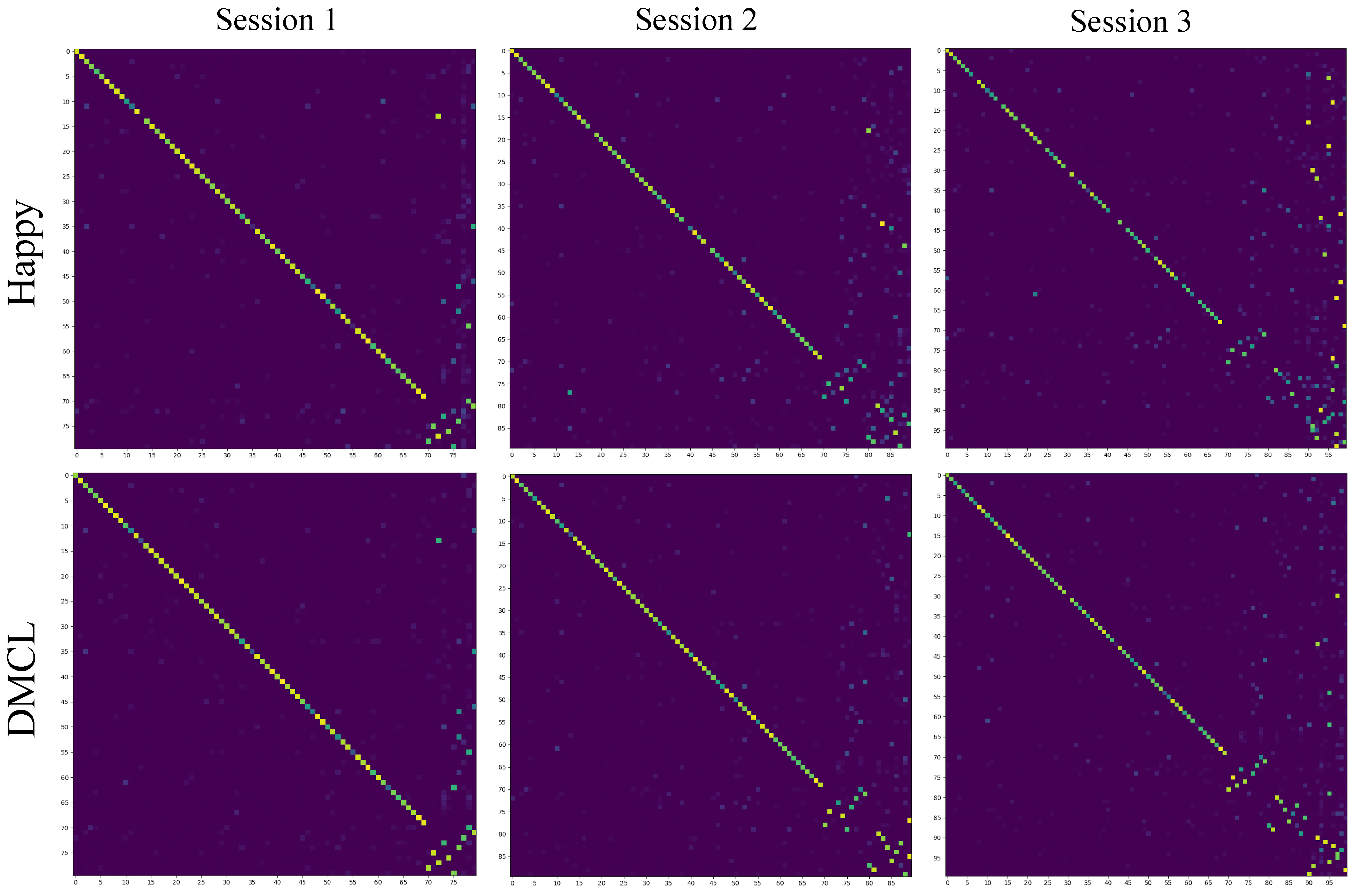

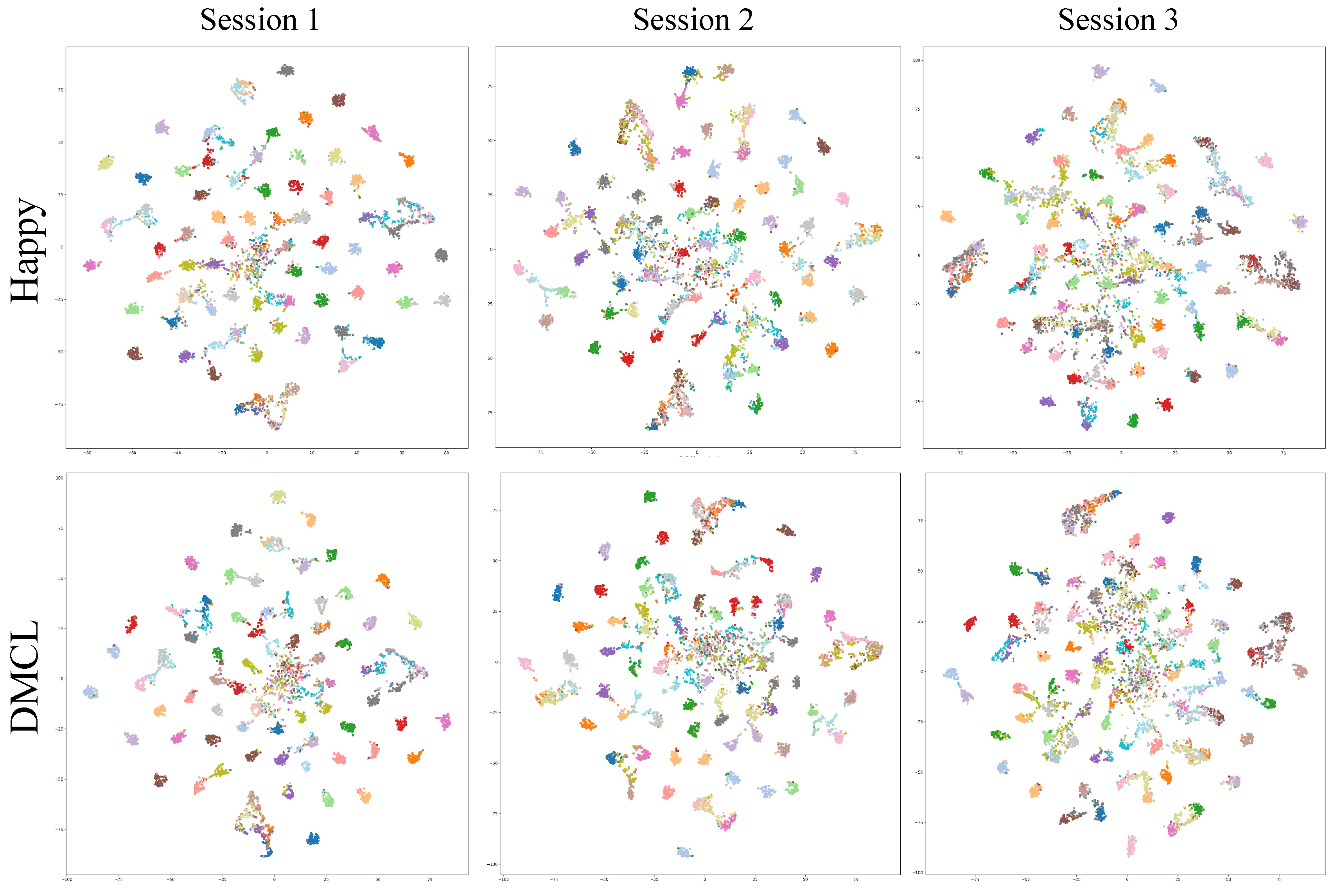

4.3.3. Visualization

We provide qualitative analysis to intuitively compare DMCL with the baseline framework.

Figure 4 presents confusion matrices on CIFAR-100 across three online sessions. DMCL produces clearer diagonal patterns compared to Happy, indicating improved classification accuracy and reduced confusion between classes. Notably, the off-diagonal elements in DMCL are significantly sparser, demonstrating that the model effectively mitigates task-level overfitting. Specifically, DMCL exhibits substantially fewer known class samples misclassified as the novel classes introduced in the current session, validating the effectiveness of dual-modal learning in maintaining stable decision boundaries.

Figure 5 visualizes feature distributions using t-SNE across three sessions. Compared to Happy, DMCL achieves better class separation with reduced overlap among semantic clusters. In Session 1, DMCL shows more compact and well-separated clusters for both known and novel classes. As sessions progress, while both methods experience increased inter-class overlap due to the accumulation of classes, DMCL consistently maintains clearer cluster boundaries. This demonstrates that incorporating textual semantics through dual-modal contrastive learning enriches feature representations and enhances discriminability, thereby alleviating semantic drift across continual learning sessions.

4.4. Ablation Study

We conduct comprehensive ablation studies to evaluate the effectiveness of each component in DMCL.

Table 4 presents results on CIFAR-100 with different configurations of dual-modal contrastive learning and fusion strategies.

Effectiveness of Dual-Modal Contrastive Learning. Comparing the baseline without dual-modal contrastive learning (row 1) to the full model with adaptive fusion (row 2), we observe substantial improvements: 29.79% gain in overall accuracy, 4.92% in known classes, and 32.80% in novel classes. This validates that incorporating textual semantics significantly enhances feature discriminability and mitigates catastrophic forgetting.

Fusion Strategy Analysis. We compare four fusion strategies: adaptive, average, concatenation, and cross-attention. Cross-attention fusion achieves the best overall performance at 76.36%, demonstrating the superiority of instance-specific dynamic weighting over fixed parameter approaches. Notably, cross-attention excels particularly on known classes (77.89% vs. 77.18% for adaptive), validating our theoretical analysis that sample-aware fusion better mitigates catastrophic forgetting. The mechanism allows old class samples (prone to forgetting) to emphasize stable textual anchors, while novel class samples leverage adaptive visual features for discovery.

Adaptive fusion achieves competitive performance at 75.22%. Examining the learned fusion coefficient reveals that visual and textual modalities contribute nearly equally to enhanced representations. This near-equal weighting provides a strong baseline but lacks the flexibility to handle samples with different plasticity–stability requirements.

Average fusion performs comparably at 74.89%, only 0.33% lower than adaptive fusion. This validates our finding that is optimal—when the learned parameter approaches 0.5, average fusion becomes effectively equivalent, offering a simpler alternative without learnable parameters.

Concatenation-based fusion achieves only 70.22% overall accuracy, substantially underperforming other strategies. This degradation stems from increased dimensionality and potential misalignment between visual and textual feature spaces, which complicates discriminative decision boundary learning. The particularly poor novel class performance (52.24%) suggests concatenation fails to effectively integrate complementary modality information.

Prompt Setting Analysis.

Table 5 presents ablation experiments validating our design choices on CIFAR-100. The most critical component is dual-modal contrastive learning. Removing it (visual-only) causes performance to drop from 76.36% to 51.67%, a substantial 24.69% degradation. Novel class accuracy is particularly affected (27.43% drop), confirming that textual semantics are essential for distinguishing newly emerged categories.

Conditional prompt generation outperforms fixed learnable prompts by 12.58% (76.36% vs. 63.78%). Instance-specific prompts capture fine-grained variations within categories, while fixed prompts apply uniformly and struggle to generalize, especially for novel classes where the gap reaches 22.69%. Our pseudo-prompt approach achieves 76.36%, reasonably close to the oracle using ground-truth text (82.42%). The 6.06% gap demonstrates that conditional generation effectively synthesizes discriminative descriptions without requiring manual annotations.

These results confirm that textual information and instance-specific generation are both essential for effective continual category discovery.

4.5. Novel Class Number Estimation

Previous experiments assume the number of novel classes is known a priori for fair comparison. However, automatic class number estimation is crucial for practical applications.

Table 6 presents results under the class-agnostic setting on CIFAR-100, where we employ a hybrid estimation strategy combining Silhouette Score and Elbow Method to automatically determine novel class numbers. PromptCCD adopts a non-parametric classifier, which has inherent advantages in class-agnostic scenarios due to flexible output dimensionality. In contrast, Happy and our method employ parametric classifiers, requiring additional estimation mechanisms before training.

Despite this structural disadvantage, our method achieves the best overall accuracy at 67.20%, surpassing PromptCCD at 59.12%, Happy at 66.80%, and GM at 53.33%. For individual metrics, PromptCCD leads on both known classes at 77.62% and novel classes at 53.70%. Our method ranks second on both categories: 72.00% for known classes and 51.26% for novel classes, outperforming Happy at 70.56% and 48.84%, respectively.

These results validate that our dual-modal learning framework maintains robustness when class numbers are estimated rather than known, highlighting practical applicability in real-world continual learning scenarios.

4.6. Complexity Analysis

Table 7 presents complexity and efficiency metrics on CIFAR-100. Our model requires 92.0 M parameters, 16.87 GFLOPs per image, and 3.77 GB peak memory. Compared to visual-only baselines, the dual-modal components add approximately 6.2 M parameters (7.2% increase) and 0.67 GFLOPs (4.1% increase). This modest overhead yields substantial performance gains: 76.36% accuracy versus 65.89% for the baseline (10.47% improvement).

Inference efficiency remains strong at 1.01 ms per sample, achieving 986.94 FPS throughput and 16.65 TFLOPS. Training takes approximately 57 s per epoch, with novel class clustering requiring only 2–3 s per session. The pseudo-prompt generation adds negligible latency (0.05 ms per sample).

These results demonstrate a favorable trade-off: less than 5% computational overhead achieves over 10% accuracy improvement, validating our approach’s efficiency and practical applicability.