1. Introduction

In recent years, the volume-based centralized drug procurement (VBP) system has become a crucial pillar of China’s medical and pharmaceutical reform. Its primary objective is to reduce drug prices, regulate distribution channels, and enhance the efficiency of medical insurance funds through large-scale procurement and price negotiation mechanisms. Within this policy framework, the Group Purchasing Organization (GPO) serves as a central intermediary, assuming key functions such as price negotiation, contract coordination, risk sharing, and benefit compensation [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, the multi-agent nature of the pharmaceutical supply chain implies that its operation is far from a static optimization problem—it is instead a complex nonlinear dynamic system [

7,

8,

9]. The GPO, hospitals, and pharmaceutical suppliers differ significantly in their objectives, risk perceptions, and cooperation incentives. Consequently, conflicts of interest and unstable cooperation frequently arise during policy implementation. In particular, when the compensation mechanism is imperfect, bad-debt risks increase, or fiscal incentives are insufficient, some participants may choose to “free ride” or withdraw from collaboration, thereby reducing the overall efficiency of the system [

10,

11,

12,

13]. It is noteworthy that the dynamic mechanisms and collaborative governance of supply chain networks have recently become significant topics at the fore of multiple disciplines, including operations research, systems science, and management science. Cross-disciplinary studies consistently reveal that supply chain systems often exhibit complex features such as nonlinearity, adaptability, and multi-equilibrium dynamics, which cannot be adequately captured by static optimization models [

14,

15,

16]. Therefore, integrating evolutionary game theory with optimal control methods provides a new analytical paradigm for investigating multi-agent interactions, incentive coordination, and policy regulation within the context of pharmaceutical group purchasing.

From the perspective of systems science and applied mathematics, the pharmaceutical group purchasing mechanism can be abstracted as a multi-agent nonlinear game system [

17,

18]. Traditional game theory, which assumes complete rationality, fails to capture learning and imitation behaviors observed in real-world decision environments. By contrast, evolutionary game theory offers mathematical tools for modeling bounded rationality within dynamic populations. Its core idea is that individual strategies evolve according to payoff differences, and population strategy distributions change over time until a stable equilibrium is reached [

19,

20,

21]. The replicator dynamics provide a rigorous description of how the proportions of strategies evolve in the population, enabling an analysis of long-term stability under different policy or institutional settings [

22,

23,

24]. In this context, the GPO’s compensation level directly affects hospitals’ willingness to participate; the hospitals’ cooperation ratio determines suppliers’ bargaining positions and expected revenues; and the suppliers’ participation level, in turn, influences the GPO’s overall performance and risk exposure. These interdependencies form a nonlinear coupling feedback loop, in which system stability and equilibrium structure depend not only on parameter values but also on the agents’ evolutionary speeds and behavioral sensitivities. By examining system trajectories under different parameter configurations, one can characterize the long-term evolution of cooperative behavior and evaluate the incentive effects of institutional design.

Most existing studies, however, treat the compensation mechanism as an exogenous parameter, assuming that the GPO adjusts its strategy under a fixed compensation level. In practice, the compensation intensity is often dynamically regulated by higher-level authorities such as health insurance departments or governmental agencies. The regulator’s goal is not to maximize the payoff of a single agent but to optimize overall social welfare under fiscal constraints. Consequently, the compensation intensity should be adaptively adjusted based on the current system state to balance cooperation stability, fiscal expenditure, and social welfare. This dynamic process can be formalized as a controlled evolutionary game model, essentially a state-dependent optimal control problem. Specifically, the regulator dynamically adjusts the control variable

to steer the system toward a cooperative region while mitigating fiscal pressure. This modifies the traditional evolutionary game framework by embedding the replicator dynamics within an optimal control system, thereby linking behavioral evolution with real-time regulatory intervention. The instantaneous social payoff function incorporates both the average payoffs of all agents and the fiscal cost of compensation, while the discounted cumulative payoff represents long-term social welfare. The optimal compensation path can thus be characterized by the Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman (HJB) equation, which establishes the dynamic relationship among compensation, system state, and optimal social utility [

25,

26,

27]. Methodologically, the proposed framework integrates nonlinear dynamical system analysis, evolutionary game theory, and optimal control theory. The replicator dynamics describe the evolution of strategic behavior; the Jacobian matrix analysis provides local stability criteria; and the HJB equation yields the optimal control law [

28,

29]. This combined framework also addresses several limitations in existing research, such as the neglect of endogenous regulatory adjustments, the lack of state-dependent incentive mechanisms, and the insufficient mathematical characterization of long-run cooperative stability. Together, these components form a unified analytical pathway, from dynamic stability to optimal regulation and policy feedback, offering a rigorous mathematical foundation for policy optimization in pharmaceutical group purchasing. For policymakers, this model enables the simulation of dynamic outcomes under different compensation schemes and provides quantitative metrics to evaluate marginal policy effects. For researchers, it also offers a reproducible and generalizable methodological foundation that bridges static incentive design and dynamic behavioral evolution—two aspects that are often analyzed separately in the existing literature.

In summary, this study develops a tripartite evolutionary game model for pharmaceutical group purchasing, focusing on the dynamic evolution of cooperation under benefit compensation and risk constraints. Building on this foundation, an optimal control mechanism is introduced to derive the optimal compensation strategy and the corresponding closed-loop evolutionary trajectory. The main contributions of this paper are threefold: (1) From a dynamic perspective, it reveals the internal mechanism of cooperative evolution in group purchasing systems. (2) By employing Jacobian matrix and eigenvalue analysis, it characterizes the existence and stability conditions of cooperative and non-cooperative equilibria. (3) It incorporates the compensation mechanism into an optimal control framework and proposes a dynamic optimal incentive model based on the HJB equation. Additionally, this study explicitly addresses the limitations of existing work by identifying unresolved gaps in dynamic incentive design and providing a systematic mathematical framework for state-dependent compensation regulation. This research extends the intersection of evolutionary game theory and optimal control in the field of pharmaceutical policy analysis, providing a quantitative and dynamic decision-support tool for the refined governance of public procurement systems.

2. Tripartite Game Model and Replicator Dynamics

To systematically characterize the dynamic interactions among Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs), hospitals, and pharmaceutical suppliers under the benefit-compensation mechanism, this paper constructs a multi-agent decision model based on evolutionary game theory. Unlike traditional static game models that only analyze one-shot equilibria, this study focuses on the time-evolving process of agents’ strategies under bounded rationality. By introducing replicator dynamic equations, the behavioral adjustment rules of the three parties under incentive and learning mechanisms are described.

Accordingly, this section first defines the basic assumptions and notations of the model, clarifying the strategy sets, payoff structures, and cost components of the three types of agents. On this basis, the expected and average payoffs of each party are derived, followed by the formulation of the corresponding replicator dynamic equations. These results provide the mathematical foundation for subsequent stability analysis and optimal control design.

2.1. Basic Assumptions and Notations of the Tripartite Game Model

To systematically describe the strategic interaction and behavioral evolution among the Group Purchasing Organization (GPO), hospitals, and pharmaceutical suppliers under the benefit-compensation mechanism, this study develops a tripartite evolutionary game model within the framework of bounded rationality and dynamic learning. Each agent updates its strategy based on historical payoffs, and behavioral adaptation occurs through imitation, adjustment, and feedback. The GPO, as the central coordinating body, undertakes policy incentives and risk-sharing functions; hospitals make decisions depending on the procurement cost savings and reputational gains brought by participation; and suppliers’ choices are influenced by profit margins, market share, and bad-debt risks. The interaction of these three agents collectively determines the system’s stability and cooperation level. To facilitate model representation and parameter specification,

Table 1 lists the main symbols and their corresponding economic meanings. All parameters have explicit behavioral interpretations and quantitative bases for subsequent modeling and numerical simulations.

Assumption 1. The system consists of three types of bounded-rational agents: the GPO (denoted as G), hospitals (denoted as H), and pharmaceutical suppliers (denoted as S). Their respective strategy sets are: , , . Here, “Compensate’’ refers to the GPO providing financial incentives to encourage hospital participation in centralized procurement; “Join’’ denotes a hospital’s decision to join the group purchasing scheme; and “Participate’’ represents the supplier’s engagement in group purchasing and contractual drug supply.

Assumption 2. Let x, y, and z denote the proportions of GPOs, hospitals, and suppliers, respectively, that adopt the cooperative strategy in a bounded-rational population. Specifically, a fraction x of GPOs choose “Compensate’’ (and choose “Not Compensate’’); a fraction y of hospitals choose “Join’’ (and choose “Not Join’’); and a fraction z of suppliers choose “Participate’’ (and choose “Not Participate’’). Thus, the system state is described by the vector with , reflecting population frequencies consistent with the interpretation of replicator dynamics.

Assumption 3. When implementing compensation, the GPO must invest additional human, material, and financial resources, incurring a compensation cost . Without compensation, it only bears regular administrative costs , where . Thus, compensation behavior can promote cooperation diffusion but increases organizational costs. Economically, reflects the fiscal burden associated with incentive delivery, while the difference captures the additional cost required to change hospital behavior.

Assumption 4. After joining the group purchasing scheme, hospitals obtain cost-saving benefits from suppliers offering lower prices, whereas non-joining hospitals receive only limited bargaining benefits . Given the economies of scale in centralized procurement, it holds that . Here, represents the synergy-driven savings attributed to volume-based purchasing, while reflects the marginal negotiation advantage retained outside the alliance.

Assumption 5. To overcome the “cold start’’ problem, hospitals’ initial willingness to join is assumed to be low. If a hospital chooses “not to join,’’ it must procure independently at cost ; if it chooses “to join,’’ the cost is , with . Hence, participation in centralized procurement reduces cost and improves efficiency. The cost gap measures the procurement efficiency gain achieved through centralized purchasing.

Assumption 6. Suppliers participating in centralized procurement gain scale benefits J, spread fixed costs, and secure stable orders. Let and denote the supplier’s costs for participating and not participating, respectively, and H the bad-debt loss. Typically, , implying that participation improves operational efficiency. J captures economies of scale generated by bulk supply contracts, while H represents the penalty imposed by delayed payments and credit risk, which are common in real-world pharmaceutical settlement practices.

Assumption 7. Through centralized procurement, the GPO integrates the pharmaceutical supply chain, obtaining policy and reputational benefits as well as synergistic gains from hospitals and suppliers . When full cooperation occurs, the GPO’s total payoff iswhere B represents compensation payments to hospitals. Without compensation, the GPO’s payoff becomesEvidently, , indicating that moderate compensation can enhance overall revenue. S and reflect policy compliance effects and institutional reputation enhancement, both of which strengthen long-term bargaining power and procurement legitimacy. Assumption 8. When all three parties adopt cooperative strategies (Compensate, Join, Participate), the total system payoff reaches its maximum, satisfyingThis demonstrates that, within an appropriate parameter range, the compensation mechanism promotes cooperation and ensures economic sustainability. This inequality defines the feasible region under which centralized procurement yields net welfare gains compared with decentralized bilateral negotiation. Based on the above assumptions, the tripartite payoff matrix is shown in

Table 2.

2.2. Expected Payoffs and Replicator Dynamic Equations of the Three Parties

From the tripartite payoff matrix in

Table 2, let the probability that the GPO chooses “Compensate” be

x, the probability that hospitals choose “Join” be

y, and the probability that suppliers choose “Participate” be

z. Then, the expected payoffs of the three agents under different strategies can be derived as follows.

- (1)

GPO’s Expected Payoff.

When the GPO chooses “Compensate,” its expected payoff is

When the GPO chooses “No Compensation,” its expected payoff is

Hence, the GPO’s average expected payoff is

- (2)

Hospital’s Expected Payoff.

When hospitals choose “Join,” their expected payoff is

When hospitals choose “Not Join,” the expected payoff is

The average expected payoff of hospitals is

- (3)

Supplier’s Expected Payoff.

When suppliers choose “Participate,” their expected payoff is

When suppliers choose “Not Participate,” their expected payoff is

Thus, the suppliers’ average expected payoff is

- (4)

Replicator Dynamic Equations.

Under bounded rationality and the imitation-learning mechanism, the strategy proportions of the three agents evolve over time according to the standard two-strategy replicator dynamics. According to the framework of Taylor and Jonker [

30], we obtain the following:

where

are given by Equations (

1)–(

3),

by Equations (

4)–(

6), and

by Equations (

7)–(

9).

Let

then the equilibrium point

of the replicator dynamics satisfies

Because each component is structured as “”, the equilibrium points include both boundary (pure-strategy) equilibria and interior (mixed-strategy) equilibria.

(1) When any of

equals 0 or 1, the corresponding component vanishes, yielding eight vertex-type equilibria:

which correspond to all combinations of full cooperation or non-cooperation among the three parties.

(2) For an interior equilibrium point to exist, with

, the three payoff differences must simultaneously vanish:

Substituting the definitions of each payoff function yields the explicit expressions:

Solving

,

, and

yields the coordinates of the interior equilibrium point. The GPO’s indifference condition determines

:

which is valid only if

. The hospital’s indifference condition determines

:

where

ensures a positive denominator, and thus

lies within a feasible range

.

The supplier’s indifference condition gives another expression for

:

which is feasible when

and

.

Since

appears in both the GPO’s and supplier’s indifference conditions, consistency requires:

Only when Equation (

13) holds and the solutions satisfy

and

does the system possess a genuine interior (mixed) equilibrium

. Otherwise, the dynamical system admits only the eight boundary equilibria and no interior fixed point. It is worth emphasizing that, although the indifference conditions for hospitals and suppliers uniquely determine

and

, the equilibrium value

for the GPO behaves fundamentally differently. From the GPO’s replicator dynamic,

, the payoff difference

depends solely on the pair

rather than on

x itself. Consequently, the interior equilibrium condition for the GPO collapses to

, which restricts

but does not uniquely determine

. Once the indifference conditions for hospitals and suppliers are satisfied, any

leads to

. Hence, the system admits a continuum of interior equilibrium points along the surface

. Economically, this indicates that the GPO’s compensation strategy becomes payoff-neutral at equilibrium: its marginal incentive to increase or reduce compensation vanishes once the cooperating levels of hospitals and suppliers reach

. As a result, the long-run trajectory of

may depend on initial conditions rather than being uniquely determined by the payoff structure, in contrast to the uniquely pinned-down values of

and

.

It is worth noting that the inequality conditions required for the existence of an interior equilibrium carry clear empirical interpretations in the context of centralized drug procurement. These conditions imply that the incremental economic benefits from cooperation must sufficiently exceed the associated costs and risks for all three parties. For hospitals, this reflects the observable cost-saving advantages reported under volume-based procurement pilot programs, where reduced purchase prices and streamlined administrative processes generate net positive gains. For suppliers, the conditions correspond to scale-based revenue opportunities and improved market access that compensate for price concessions and the risk of delayed reimbursement. For the GPO, the feasibility of the condition aligns with policy practice in which compensation and regulatory support are calibrated to ensure that coordinating procurement yields operational and reputational benefits that outweigh fiscal outlays. Therefore, the mathematical feasibility conditions of the interior equilibrium are consistent with realistic procurement scenarios in which cooperation emerges only when measurable, mutually reinforcing advantages are present across the tripartite system.

2.3. Stability Analysis of Equilibrium Points

To characterize the evolutionary attractiveness of different equilibria, we linearize the system (

10) around an arbitrary state. Let

then, by Equation (

10), the replicator dynamic system can be written as

Define the payoff differences

Then the Jacobian matrix of the system at an arbitrary point

is

where

Substituting the eight vertex (pure-strategy) equilibrium points

into Equation (

17), we can obtain the Jacobian matrix at each equilibrium and thus its eigenvalues. If, at an equilibrium

, all eigenvalues of

have negative real parts, then

is locally asymptotically stable. If at least one eigenvalue has a positive real part, the equilibrium is a saddle point or unstable. The eigenvalues corresponding to the eight pure-strategy equilibria are summarized in

Table 3.

The stability results offer clear practical implications for policy design within centralized drug procurement. A locally asymptotically stable cooperative equilibrium indicates that once collaboration among the GPO, hospitals, and suppliers is formed, the system is capable of sustaining cooperation even when confronted with small fluctuations in reimbursement schedules or procurement volumes. In contrast, an equilibrium identified as unstable or a saddle point reflects a fragile form of cooperation in which relatively minor changes in cost, risk perception, or expected benefit may lead participants to withdraw or reduce commitment. These insights demonstrate that compensation and risk-sharing arrangements need to be structured not only to initiate cooperation but also to preserve it under uncertainty. A thorough understanding of the stability characteristics, therefore, assists policymakers in configuring financial incentives, risk allocation, and participation conditions in a manner that promotes resilient and sustained collaboration across the tripartite procurement system.

For replicator dynamics with two strategies per agent, a classical sufficient condition for global stability of a cooperative equilibrium is that all payoff differences are strictly positive at the boundaries, , and strictly negative in the opposite boundaries, . If these inequalities hold for all , the dynamics admit a unique globally stable interior fixed point.

2.4. Optimal Control and Evolutionary Path Analysis of the Tripartite Game

The evolutionary game results derived in the previous subsection reflect strategic adjustments under a fixed compensation level. However, a static compensation policy inherently assumes that incentive intensity remains unchanged throughout the procurement cycle, which is inconsistent with real-world institutional practice. In centralized drug procurement, compensation budgets depend on fiscal pressure, participation scale, default risk, and policy phases, and regulators frequently adjust incentive levels to stabilize cooperation and prevent opportunistic withdrawal. Moreover, static compensation cannot react to temporary deviations caused by delayed payments, fluctuating supplier margins, or the entry of new hospitals. Once the system deviates from the cooperative region, fixed incentives may be insufficient to restore collaboration, resulting in reduced long-term welfare. Therefore, a dynamic feedback-driven compensation mechanism is required to continuously evaluate the system state and adjust incentives accordingly. This motivates the introduction of optimal control to design a state-dependent compensation policy that maximizes long-term social welfare while maintaining cooperation stability.

In the preceding analysis, the compensation level was treated as an exogenous constant, and the replicator dynamic system (

10) only reflected the evolution of strategy proportions under a fixed incentive mechanism. To further capture the behavior of a regulator (e.g., the health insurance authority or a higher-level government) that adjusts the compensation intensity dynamically according to the current system state, we introduce the GPO’s compensation level as a time-dependent control variable

, explicitly embedded in the payoff differences.

In modeling the effect of compensation, we adopt a linear and additive structure, which is widely used in evolutionary game models with policy intervention. The linear term represents the first-order marginal incentive provided by compensation, ensuring that the regulator’s influence shifts payoffs proportionally without imposing additional curvature or nonlinearities. This specification provides a transparent and behaviorally interpretable approximation: compensation increases perceived payoffs in a smooth and monotonic manner, while preserving the replicator dynamics’ analytical tractability. Without loss of generality, assume that compensation has a linear and gain-enhancing impact on the payoffs of the three agents, i.e.,

where

are the marginal incentive coefficients of compensation for the three agents, and

denote the payoff differences without compensation.

Accordingly, the controlled replicator dynamics can be expressed as

or compactly as

where

,

The regulator aims to maximize the discounted social welfare over an infinite time horizon. The instantaneous social payoff is defined as a weighted sum of the three agents’ expected payoffs, penalized by fiscal expenditure:

where

denote the social weights assigned to each agent’s payoff,

is the marginal fiscal cost coefficient, and the quadratic term prevents unbounded compensation escalation.

Thus, the regulator’s optimal control problem is formulated as

where

denotes the social discount rate.

Let

represent the value function, i.e., the maximal discounted social return attainable from the current state

X. Then

satisfies the infinite-horizon Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman (HJB) equation:

where

is the gradient of the value function.

Since the

u-dependent part of Equation (

23) is a quadratic function of

u, the first-order optimality condition can be derived by isolating the terms involving

u:

Differentiating

with respect to

u and setting it to zero yields

Ignoring for the moment the nonnegativity constraint

, the optimal control admits the analytical form:

Considering

, the admissible optimal feedback law becomes

Substituting Equation (

27) into the HJB Equation (

23) yields a nonlinear partial differential equation in

:

where

is given by Equation (

27). Once

or its numerical approximation is obtained, the corresponding optimal trajectory of the system is governed by

which represents the closed-loop evolutionary dynamics under optimal feedback control. Compared with the exogenous-compensation scenario, Equation (

29) reveals that when the cooperation ratio of any agent declines, the gradient of the value function motivates the regulator to temporarily increase the compensation intensity. Through the

term, the system is “pulled back” toward the high-cooperation region, thereby realizing an optimal guidance of the evolutionary process.

Given the nonlinearity of the HJB equation, we obtain

and

numerically using a finite-difference approximation on a structured grid over the state space

, combined with value iteration until convergence. This yields a numerically stable approximation of the optimal feedback law governing the regulator’s intervention. To further enhance transparency and reproducibility, a detailed Linear–Quadratic Approximation (LQA) of the nonlinear HJB problem is provided in

Appendix A. The LQA derivation includes (i) linearization of the controlled replicator dynamics, (ii) quadratic expansion of the welfare function, and (iii) the resulting algebraic Riccati equation, which yields an analytically interpretable approximation of the optimal compensation policy. This supplement complements the nonlinear numerical solution and clarifies the structural form of the optimal feedback mechanism.

3. Numerical Simulation

To verify the rationality of the proposed evolutionary game model and demonstrate the effectiveness of the optimal compensation control mechanism, this section presents a series of numerical simulations to examine the system’s stability structure and dynamic evolution characteristics. The simulation analysis is conducted in three stages. First, under the baseline parameter configuration, all equilibrium points are computed, and their Jacobian eigenvalues are evaluated to determine local stability properties. Second, the existence and behavioral features of a non-trivial internal equilibrium under moderate compensation intensity are investigated, followed by a sensitivity analysis of key parameters to assess robustness under policy variation. Finally, the evolutionary trajectories of the tripartite system are compared under fixed-compensation and optimal-feedback compensation, highlighting differences in convergence rate and cooperation depth. For consistency and interpretability, all parameters are normalized to dimensionless form.

3.1. Stability Verification

Under the parameter settings in

Table 4, the system has eight boundary equilibrium points

, corresponding to all possible pure strategy combinations of the three parties (cooperation or non-cooperation). To determine their stability, the Jacobian matrix at each equilibrium is computed and its eigenvalues

are obtained. If

, the point is locally asymptotically stable; if any

, the equilibrium is unstable. The computed results are summarized in

Table 5. As shown, under the given parameters, only

is locally asymptotically stable, indicating that full cooperation is the long-term attractor of the system. All other seven equilibria contain at least one eigenvalue with a positive real part and are thus unstable or saddle points, forming different evolutionary channels. Among them,

and

represent the most typical transitional equilibria, determining the pathway from partial to full cooperation. This suggests that when the initial level of cooperation is low, the system may experience a staged transformation from “local stability” through “perturbation breakthrough” to “global convergence.”

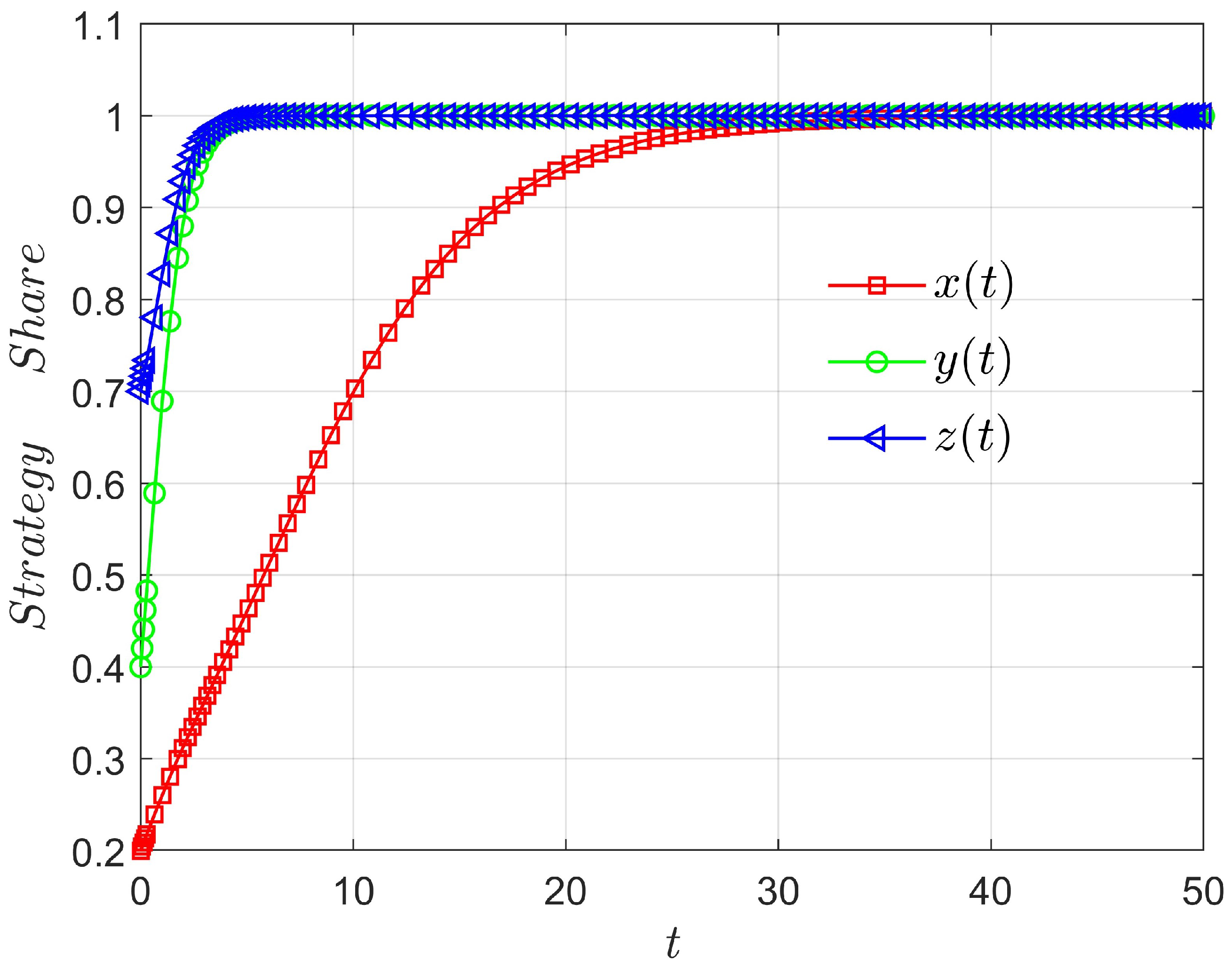

Figure 1 illustrates the time evolution of cooperation ratios for the three agents under the parameter settings in

Table 4. The horizontal axis represents time

t, and the vertical axis denotes the proportion of cooperative strategies

. The red square curve corresponds to the GPO’s compensation willingness

, the green circular curve to the hospitals’ participation ratio

, and the blue triangular curve to the suppliers’ cooperation level

. At the early stage (

), all three variables increase rapidly; the supplier, being most sensitive to incentives and higher expected payoff, reaches

first, followed by hospitals driven by supply-chain synergy. During the mid-stage (

), as positive feedback strengthens, the GPO’s compensation intention

exhibits an S-shaped growth, and the strategies of all three parties gradually align. When marginal cooperative benefits diminish, the system enters a steady phase (

), where

,

, and

stabilize near 1, implying convergence to the fully cooperative equilibrium

. This is consistent with the Jacobian analysis, where all eigenvalues at this point have negative real parts. Overall, the simulation validates the model’s stability under the given parameters: from arbitrary initial states, the system converges to the cooperative equilibrium. Suppliers respond fastest, serving as the key driver of cooperation diffusion, while hospitals and GPOs adjust more slowly but continue improving their cooperation levels under the compensation mechanism. This dynamic pattern aligns with bounded rational learning behavior, demonstrating that under reasonable benefit allocation and cost constraints, the agents can spontaneously achieve sustained cooperation—providing theoretical support for the design of optimal compensation mechanisms.

To further verify nonlinear behavior, we analyze the internal equilibrium. Solving , , and yields a unique internal solution within . The corresponding eigenvalues indicate weak stability with a spiral asymptotic pattern. This suggests that when compensation and risk remain at moderate levels, the system may form a “partial cooperation steady state,” reflecting the stage-wise and locally stable nature of real-world cooperation dynamics.

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Key Parameters

To evaluate the robustness of the evolutionary outcomes under policy variation, we perform sensitivity analysis on the hospital-side benefit

B using the baseline configuration in

Table 4. This parameter influences the payoff gap

and shapes the willingness of hospitals to participate in GPO-coordinated procurement. Since hospitals serve as the core linkage between GPOs and suppliers, changes in

B have the potential to alter the stability structure of the tripartite system and may shift the eventual cooperation state. In the analysis,

B is gradually varied within the range

. For each value, the replicator dynamics are simulated until convergence, and the corresponding equilibrium state

is recorded to observe how cooperation stability evolves with hospital incentives.

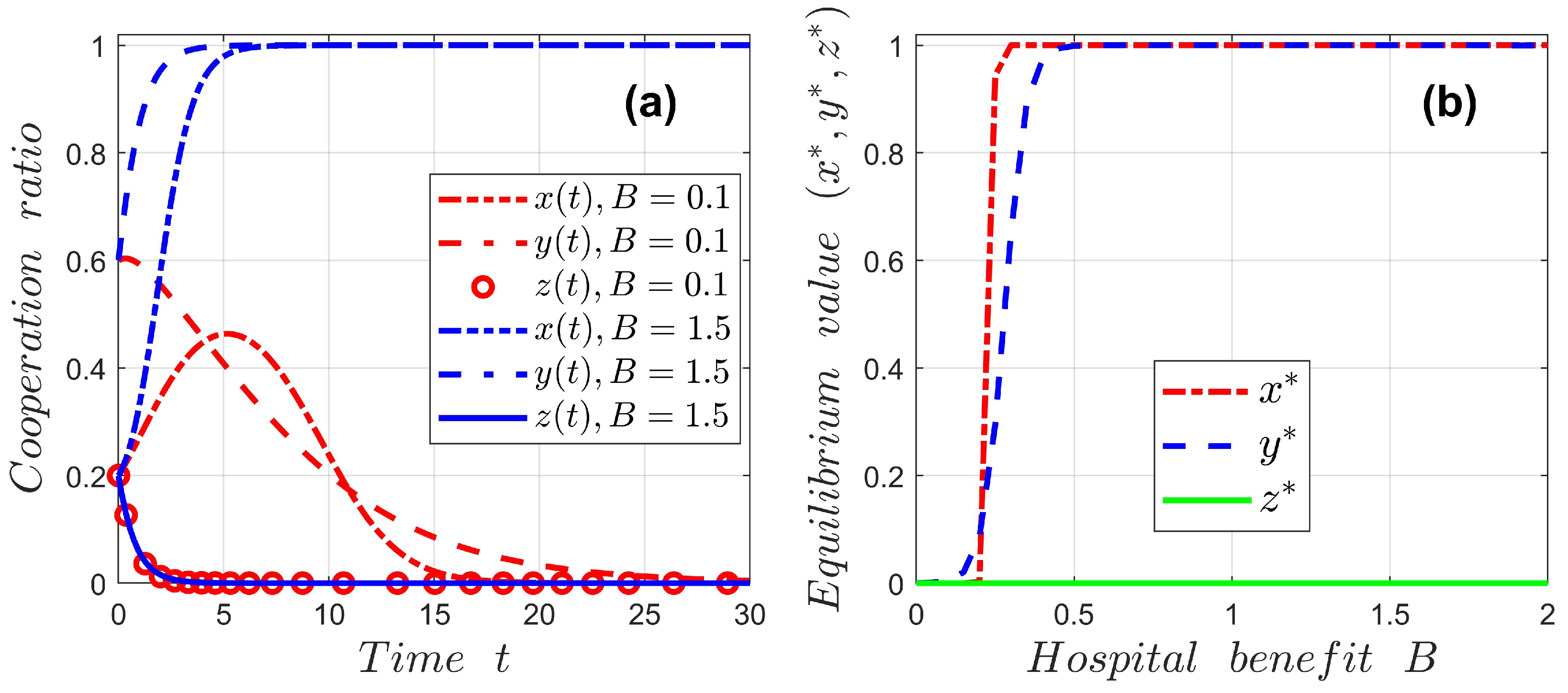

Figure 2 shows that the hospital-side benefit

B plays a decisive role in determining whether cooperation in the GPO procurement system can be sustained. As shown in

Figure 2a, when

is low, hospitals lack incentive to participate, causing their cooperation level to rapidly decline to zero; suppliers subsequently exit due to reduced market demand, and the GPO’s willingness to compensate collapses accordingly, leading the system to a non-cooperative steady state. In contrast, when

B is sufficiently high (e.g.,

), the cooperation levels of all three parties quickly increase and converge toward

, indicating a robust cooperative equilibrium with stable long-term collaboration.

Figure 2b further reveals a sharp threshold behavior once

B exceeds approximately 0.35, the equilibrium abruptly switches from near-zero cooperation to full cooperation. This sensitivity result demonstrates that enhancing hospital-side returns, such as increasing reimbursement incentives, participation rebates, or settlement advantages, can significantly accelerate cooperation diffusion and serve as an effective policy lever for achieving stable tripartite collaboration.

Beyond the hospital-side benefit

B, the stability of the evolutionary equilibria is also sensitive to other key parameters in the model, such as the cooperation cost parameters

,

, and

, which respectively represent the costs incurred by GPOs, hospitals, and suppliers when adopting cooperative strategies. These parameters directly affect the payoff differences that drive the replicator dynamics and therefore play a fundamental role in determining both the direction of strategy evolution and the local stability of the equilibria. Nevertheless, as shown in

Table 3, the eigenvalues associated with each pure-strategy equilibrium can be explicitly derived in closed form. Consequently, when all other parameters are held constant, the local stability of the equilibria under variations of any given parameter can be readily assessed through straightforward theoretical calculations by examining the signs of the corresponding eigenvalues. Owing to space limitations, we do not present these additional analytical derivations in the main text. However, the underlying procedure follows standard stability analysis of replicator dynamics and can be carried out analytically without difficulty.

3.3. Optimal Control and Evolutionary Path Analysis

Next, we compare the dynamic evolution under fixed compensation and optimal feedback compensation. Let the fiscal marginal cost coefficient be , the social discount rate , and the incentive sensitivity coefficients . The social weights are set to . The initial state is , the time interval , and the integration step . The fourth-order Runge–Kutta method is used to numerically integrate the replicator equations.

Under the fixed-compensation scenario, the compensation level is constant

, added to the GPO’s payoff difference:

where

are computed using the parameters in

Table 4.

To highlight the feedback characteristics of optimal compensation, we introduce a state-dependent compensation rule:

which can be regarded as a linearized approximation of the first-order optimality condition derived from the HJB equation. When the system is far from full cooperation, the regulator provides stronger compensation to accelerate diffusion; as cooperation increases, the compensation automatically decays—thus achieving a dynamic fiscal-cooperation balance. Substituting

into the dynamics yields the controlled system under optimal compensation:

The results can then be compared with the fixed-compensation case to examine differences in convergence rate and long-term cooperation level.

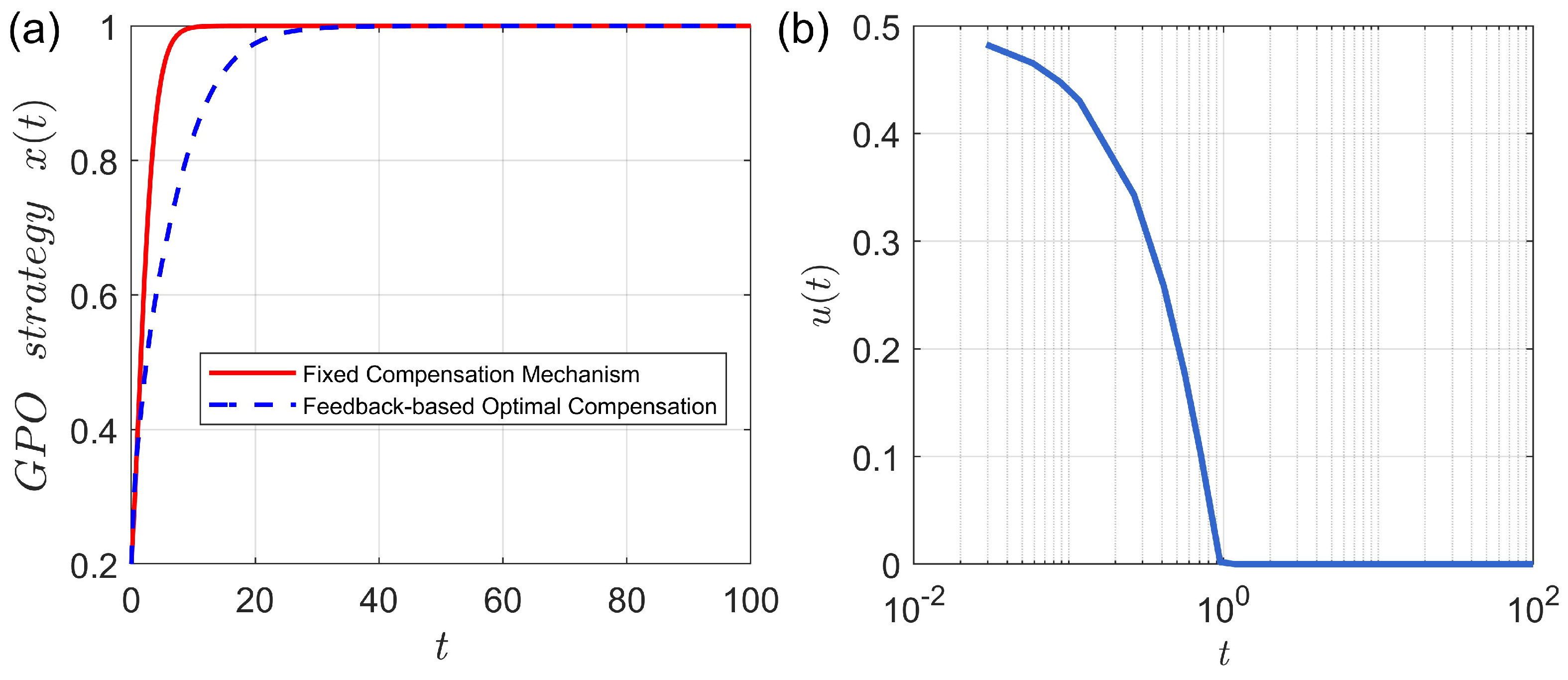

Figure 3 presents a comparison of the evolutionary dynamics under fixed and feedback-based incentive mechanisms, evaluated using the parameter values listed in

Table 4. In

Figure 3a, under fixed compensation (red curve), the GPO’s cooperation strategy

rapidly increases from

and reaches a steady state

around

, showing nearly exponential convergence. This indicates that a constant moderate compensation level (

) can quickly achieve full cooperation in the short term. However, since the incentive strength remains constant even after the system reaches high cooperation, fiscal expenditure continues, causing efficiency loss and resource waste in the long run. By contrast, under the feedback-type optimal mechanism (blue curve), the early-stage evolution is slightly slower, but the overall trajectory is smoother and still converges to

around

.

Figure 3b shows that the compensation intensity

starts high (around 0.48) to boost cooperation, then declines monotonically and approaches zero after

. This “high-initial–fast-decay” pattern reflects the optimal control law: strengthen incentives during early instability and gradually withdraw them once cooperation diffuses. Hence, the HJB-based optimal compensation achieves dynamic optimization of both evolution speed and fiscal efficiency, ensuring convergence to the cooperative equilibrium while minimizing expenditure. The results confirm that the proposed optimal control framework not only captures the mathematical nature of the evolutionary game but also provides quantitative guidance for practical GPO policy design—enabling regulators to dynamically guide cooperation behavior within fiscal constraints, thereby maximizing social welfare and minimizing cost.

4. Conclusions

This paper develops a dynamic analytical framework that integrates evolutionary game theory and optimal control to investigate multi-agent cooperation and incentive mechanisms in the GPO system. The model includes three bounded-rational agents, namely GPOs, hospitals, and pharmaceutical suppliers, and incorporates multiple real-world factors such as compensation, bad-debt risk, cost structure, and fiscal constraints. The tripartite evolutionary game model and the corresponding replicator dynamics describe how each agent adapts strategies through imitation and learning, thereby revealing the deep influence of compensation on cooperative evolution and stability. Under static settings, eight boundary equilibria and possible internal mixed equilibria are derived. Jacobian linearization and eigenvalue analysis reveal diverse dynamic modes across parameter regions, reflecting the nonlinear nature of pharmaceutical procurement systems. Introducing compensation expands the cooperation domain and confirms that moderate incentives enhance cooperation and improve benefit allocation. Furthermore, embedding the GPO compensation level into an optimal control framework through the Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman equation yields a feedback-based optimal compensation mechanism. The resulting optimal rule adjusts incentive strength dynamically according to system states and balances fiscal cost with cooperative gains. Simulation results demonstrate that the optimal compensation policy accelerates cooperation in early stages and alleviates fiscal burden in later stages, leading to faster convergence and higher overall welfare when compared with a fixed compensation scheme.

From a policy perspective, this study presents several actionable insights for improving the design and governance of centralized drug procurement. First, the results show that hospital-side incentives are a key determinant of cooperation stability. Strengthening reimbursement bonuses, participation rebates, and priority in settlement can help maintain hospitals’ willingness to participate. Second, suppliers’ exposure to risk, especially the risk of delayed or defaulted payments, should be reduced through transparent settlement schedules or shared mechanisms for preventing default, since these factors strongly influence suppliers’ strategic decisions. Third, the optimal control analysis indicates that compensation should not remain fixed throughout the procurement cycle. Instead, regulators are encouraged to adopt a state-dependent and feedback-based adjustment rule that increases compensation when cooperative behavior weakens and gradually reduces compensation once participation becomes stable. This approach can improve fiscal efficiency. In practice, policymakers may implement dynamic monitoring of cooperation indicators, such as supplier participation rates, hospital procurement compliance, and payment timeliness, and link compensation intensity to these indicators. Such a mechanism can help regulatory authorities prevent sudden cooperation breakdowns and sustain system stability despite fluctuations in demand, pricing, or fiscal conditions.

Despite its contributions, this study is subject to several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the evolutionary dynamics are formulated in a deterministic framework and do not explicitly account for stochastic shocks, such as sudden policy changes, demand volatility, or unexpected supply disruptions. Second, the model assumes homogeneous agent populations within each group, thereby abstracting from heterogeneity in hospital size, supplier capacity, or regional policy environments. Third, the compensation effect is modeled as linear and additive for analytical tractability, which may oversimplify nonlinear or threshold-based incentive responses observed in practice. Finally, the model presumes complete information regarding payoff structures and behavioral responses, whereas real-world procurement systems often operate under information asymmetry and institutional constraints. These limitations delineate the scope of applicability of the current framework and provide clear directions for future extensions.

Although the present model is theoretical, many parameters can be estimated or calibrated empirically using existing procurement and hospital operation data. Hospital-side benefits represented by B may be inferred from procurement savings or reimbursement adjustments. Supplier-related parameters such as H and can be estimated from historical records of bad debt and audited production or logistics costs. GPO-related benefits such as S and may be linked to administrative performance metrics or policy subsidy information. In addition, the transition rates embedded in the replicator dynamics can be calibrated from behavioral data reflecting participation frequency, compliance behavior, and changes in procurement volume. Incorporating empirical calibration in future work would allow the model to serve as a practical component of real decision-support systems and further enhance its policy relevance.

In summary, the main contributions of this study can be presented as follows. (1) The study integrates evolutionary game dynamics and optimal control into a unified framework for the analysis of policy incentives and multi-agent behavioral evolution. (2) It introduces an HJB-based dynamic incentive optimization method that provides a computable feedback design suitable for complex adaptive systems. (3) It offers quantitative insights that support policy optimization in pharmaceutical procurement, healthcare supply chains, and broader public resource allocation contexts. Future research may extend this framework by incorporating stochastic disturbances, incomplete information, heterogeneous learning behaviors, or multi-regional procurement networks in order to strengthen its applicability and robustness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, Z.L. and Y.W.; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, Z.L. and Y.W.; visualization, supervision, Z.L.; funding acquisition, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the General Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72274082); Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71804062); Jiangsu Provincial Social Science Foundation (No. 22GLB019); and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2018M642188).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Linear–Quadratic Approximation of the Optimal Control Problem

To provide additional analytical insight into the structure of the optimal compensation policy and to enhance the reproducibility of our results, this appendix presents a linear–quadratic approximation (LQA) of the nonlinear Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman (HJB) problem introduced in

Section 2. The central idea is to approximate the nonlinear controlled evolutionary system and the instantaneous social payoff in a neighborhood of a given nominal operating point, and then apply the standard linear–quadratic regulator (LQR) framework.

Appendix A.1. Linearization of the Controlled Evolutionary Dynamics

Recall that the controlled replicator dynamics in Equation (

19) can be written in compact form as

where

denotes the cooperation ratios of the GPO, hospitals, and suppliers, respectively, and

is the compensation intensity. Let

be a reference operating point, typically chosen as a steady state of the deterministic system, i.e.,

In the main text, a natural choice is the fully cooperative equilibrium

together with a steady-state compensation

that maintains this equilibrium.

Define the deviation variables

A first-order Taylor expansion of the drift term around

gives

Neglecting higher-order terms yields the linearized system

with

The matrices

A and

B can be computed explicitly from

and

as defined in the main text.

Appendix A.2. Quadratic Approximation of the Instantaneous Payoff

The instantaneous social payoff from Equation (

22) is

where

are the social weights and

is the marginal fiscal cost coefficient. To align with the LQR structure, we consider the equivalent minimization of the negative payoff

Expanding

in a second-order Taylor series around

and discarding constant and linear terms (which do not affect the optimal feedback) yields the following:

where

and

are given by

This leads to the quadratic cost functional

subject to the linear dynamics in Equation (

A5).

Appendix A.3. LQA Form of the HJB Equation and the Algebraic Riccati Equation

Under the LQA, the value function takes the quadratic form

where

is a symmetric matrix to be determined. The HJB equation becomes

The minimizer is obtained by taking the derivative with respect to

v:

Substituting

into the HJB equation and equating quadratic terms in

yields the continuous-time Algebraic Riccati Equation (ARE):

The matrix

P can be obtained numerically (e.g., via Schur decomposition or control toolbox routines).

Appendix A.4. Approximate Optimal Compensation Law and Interpretation

Once

P is solved from the ARE, the LQA-based approximate optimal compensation law is

Thus, near the reference operating point, the optimal compensation intensity is an affine function of deviations in the cooperation ratios. Economically, this approximation expresses the optimal balance between improving instantaneous social welfare and limiting fiscal expenditure.

References

- Nollet, J.; Beaulieu, M. The Development of Group Purchasing: An Empirical Study in the Healthcare Sector. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2013, 9, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.H.; Schwarz, L.B. Controversial Role of GPOs in Healthcare-product Supply Chains. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2011, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.C.; Cheng, H.K.; Ding, C.; Li, S. To Join or Not to Join Group Purchasing Organization: A Vendor’s Decision. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 258, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, R.L.; Seidmann, A.; Tilson, V. The Impact of Custom Contracting and the Infomediary Role of Healthcare GPOs. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2018, 28, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaba, O.; Tan, B. Analysis of a Group Purchasing Organization under Demand and Price Uncertainty. Flex. Serv. Manuf. J. 2018, 30, 844–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, C.; Hsuan, J. Collaborative Purchasing of Complex Technologies in Healthcare: Implications for Alignment Strategies. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2015, 35, 430–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, E.B.; Pierre, R.; Carter, S.; Bond, A.M. Role of Supply Chain Intermediaries in Steering Hospital Product Choice: Group Purchasing Organizations and Biosimilars. Health Aff. Sch. 2024, 2, qxae067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.T.; Keskinocak, P.; Orenstein, W.A.; Toktay, L.B. A Mixed Integer Programming Model for Vaccine Pricing within a Group Purchasing Organization. Vaccine 2024, 42, 1892–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.M.; McAlearney, J.S.; Sharma, L.; Kim, Y.H. Examining the Financial and Quality Performance Effects of Group Purchasing Organizations. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2021, 46, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimon, G.; Babenko, V.; Sadowska, B.; Chudy-Laskowska, K.; Gosik, B. Inventory Management in SMEs Operating in Polish Group Purchasing Organizations during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Risks 2021, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja, K. Drug Shortages and Group Purchasing Organizations. JAMA 2020, 324, 808–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.; Heydari, M.; Pishvaee, M.S.; Teimoury, E. Strategic Decisions to Join Group Purchasing Organizations. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 149, 106869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Langdo, J.; Hwang, D.; Marques, V.; Hwang, P. Impacts of Distributors and Group Purchasing Organizations on Hospital Efficiency and Profitability: A Bilateral Data Envelopment Analysis Model. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2023, 30, 476–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Chen, L.Y.; Battino, M.; Farag, M.A.; Xiao, J.B.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Gao, H.Y.; Jiang, W.B. Blockchain: An Emerging Novel Technology to Upgrade the Current Fresh Fruit Supply Chain. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 124, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonah, E.; Huang, X.Y.; Aheto, J.H.; Osae, R. Application of Electronic Nose as a Non-invasive Technique for Odor Fingerprinting and Detection of Bacterial Foodborne Pathogens: A Review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 1977–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.W.; Xu, J.; Shi, G.Y.; Huang, X.Y. Evaluation and Countermeasures for the Secure Supply of Fruit and Vegetable Products in Jiangyin, China. Agro Food Ind. Hi-Tech 2016, 27, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Zhang, Q. Incentives for Corporate Social Responsibility in a Group-purchasing Supply Chain under Cooperation and Competition. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2024, 32, 267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Li, W.; Song, X.; Sun, B.; Gong, G. A Fuzzy Group Decision-making-based Method for Green Supplier Selection and Order Allocation. J. Syst. Simul. 2023, 35, 2133–2149. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, H.M. The Collective Strategies of Key Stakeholders in Sponge City Construction: A Tripartite Game Analysis of Governments, Developers, and Consumers. Water 2020, 12, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhao, J.T.; Liu, J.C.; Yu, J. An Evolutionary Game Approach to Enhancing Semiconductor Supply Chain Security in China: Collaborative Governance and Policy Optimization. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Liu, J.Y.; Ge, J.W. Dynamic Game in Agriculture and Industry Cross-sectoral Water Pollution Governance in Developing Countries. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 243, 106417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi-Zangeneh, S.; Shams-Gharneh, N.; Gossner, O. Two-Sided Matching with Bounded Rationality: A Stochastic Framework for Personnel Selection. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.M.; Liu, R.Z.; Shahzad, F. Stackelberg Game Analysis of Green Design and Coordination in a Retailer-Led Supply Chain with Altruistic Preferences. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.F.; Wu, J.Y.; Zhu, M.T.; Wang, M.C. Dynamic Stochastic Game Models for Collaborative Emergency Response in a Two-Tier Disaster Relief System. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasseigne, E.; Reis, R.C.; Sastre-Gómez, S. Unbounded Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman Equations with One Co-dimensional Discontinuities. Nonlinear Differ. Equ. Appl. (NoDEA) 2025, 33, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, H.; Tai, H.M.; Qiu, J.N. Viscosity Solutions of a Class of Second Order Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman Equations in the Wasserstein Space. Appl. Math. Optim. 2025, 91, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Fang, S.X.; Zhou, T. SOC-MARTNET: A Martingale Neural Network for the Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman Equation without Explicit infu∈U H in Stochastic Optimal Controls. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2025, 47, C795–C819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, R.; Auriol, J.; Bribiesca-Argomedo, F.; Krstic, M. Backstepping for Partial Differential Equations: A Survey. Automatica 2026, 183, 112572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xing, H.Y.; Zhang, P.; Li, Z.W. Evolutionary Game Analysis of Liquefied Natural Gas Import Supply Chain Trading and Shipping Cooperation under “Energy Dilemma”. Energy Sources Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 2025, 20, 2489430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.D.; Jonker, L.B. Evolutionary Stable Strategies and Game Dynamics. Math. Biosci. 1978, 40, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |