MCARSMA: A Multi-Level Cross-Modal Attention Fusion Framework for Accurate RNA–Small Molecule Affinity Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

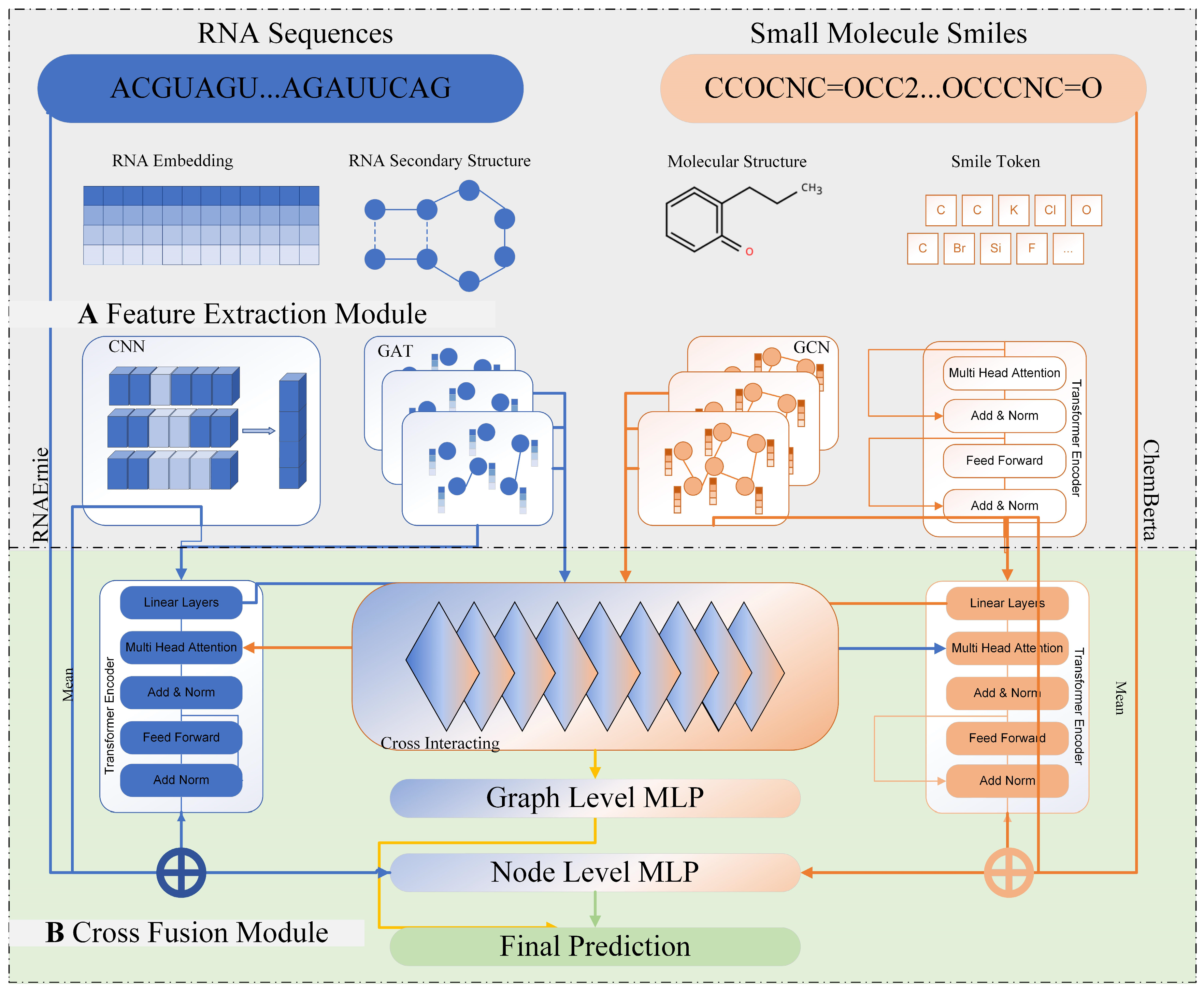

2.1. Model Overview

2.2. Feature Extraction Module

2.2.1. RNA Feature Extraction

2.2.2. Small Molecule Feature Extraction

2.3. RNA–Small Molecule Cross-Information Fusion

2.3.1. Atom–Nucleotide Fine-Grained Interaction

2.3.2. Structure-Guided Multi-Level Interaction

2.3.3. Adaptive Fusion via Gating Network

3. Results

3.1. Datasets and Baselines

3.2. Cross-Validation Results

3.3. Independent Test Results

3.4. Ablation Study

3.5. Computational Efficiency Analysis

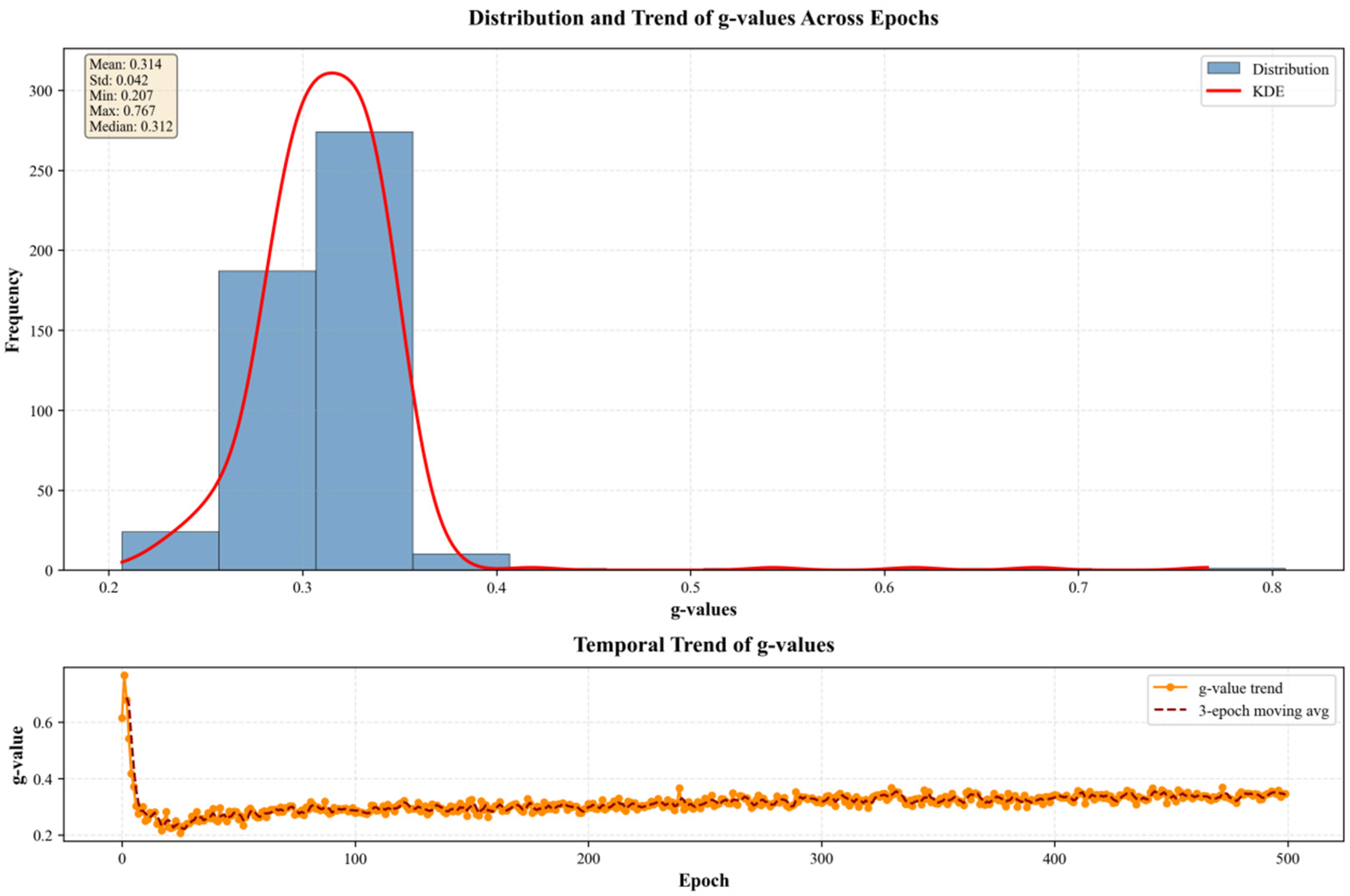

3.6. Analysis of Gating Behavior and Model Decision-Making

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 2009, 136, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Ma, R.; Cai, J.; Guo, C.; Chen, Z.; Yao, L.; Wang, Y.; Fan, R.; Shi, X.W.Y. RNA modifications: Importance in immune cell biology and related diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgs, P.G.; Lehman, N. The RNA World: Molecular cooperation at the origins of life. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottesen, E.W. ISS-N1 makes the First FDA-approved Drug for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Transl. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, K.D.; Hajdin, C.E.; Weeks, K.M. Principles for targeting RNA with drug-like small molecules. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs-Disney, J.L.; Yang, X.; Gibaut, Q.M.R.; Tong, Y.; Batey, R.T.; Disney, M.D. Targeting RNA structures with small molecules. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 736–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J.; Škalič, M.; Martínez-Rosell, G.; DeFabritiis, G. KDEEP: Protein-Ligand Absolute Binding Affinity Prediction via 3D-Convolutional Neural Networks. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2018, 58, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Kim, H.; Zhang, X.; Stevenson, A.Z.; Bennett, W.F.D.; Kirshner, D.; Wong, S.E.; Lightstone, F.C.; Allen, J.E. Improved Protein-Ligand Binding Affinity Prediction with Structure-Based Deep Fusion Inference. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 1583–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, S.D.; Afshar, M. Validation of an empirical RNA-ligand scoring function for fast flexible docking using Ribodock. J. Comput. Aided. Mol. Des. 2004, 18, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Carmona, S.; Alvarez-Garcia, D.; Foloppe, N.; Garmendia-Doval, A.B.; Juhos, S.; Schmidtke, P.; Barril, X.; Hubbard, R.E.; Morley, S.D. rDock: A fast, versatile and open source program for docking ligands to proteins and nucleic acids. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodsell, D.S.; Sanner, M.F.; Olson, A.J.; Forli, S. The AutoDock suite at 30. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, P.T.; Brozell, S.R.; Mukherjee, S.; Pettersen, E.F.; Meng, E.C.; Thomas, V.; Rizzo, R.C.; Case, D.A.; James, T.L.; Kuntz, I.D. DOCK 6: Combining techniques to model RNA-small molecule complexes. RNA 2009, 15, 1219–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wu, Q.; Huang, S.Y. NLDock: A Fast Nucleic Acid-Ligand Docking Algorithm for Modeling RNA/DNA-Ligand Complexes. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 4771–4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philips, A.; Milanowska, K.; Lach, G.; Bujnicki, J.M. LigandRNA: Computational predictor of RNA-ligand interactions. RNA 2013, 19, 1605–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Wang, J. SPA-LN: A scoring function of ligand-nucleic acid interactions via optimizing both specificity and affinity. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2017, 45, e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwiczak, O.; Antczak, M.; Szachniuk, M. Assessing interface accuracy in macromolecular complexes. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0319917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithin, C.; Kmiecik, S.; Błaszczyk, R.; Nowicka, J.; Tuszyńska, I. Comparative analysis of RNA 3D structure prediction methods: Towards enhanced modeling of RNA-ligand interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 7465–7486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, P.; Gohlke, H. DrugScore: RNA-knowledge-based scoring function to predict RNA-ligand interactions. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007, 47, 1868–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tor, Y. Targeting RNA with small molecules. ChemBioChem 2003, 4, 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairys, V.; Baranauskiene, L.; Kazlauskiene, M.; Matulis, D.; Kazlauskas, E. Binding affinity in drug design: Experimental and computational techniques. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2019, 14, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilbert, C.; James, T.L. Docking to RNA via root-mean-square-deviation-driven energy minimization with flexible ligands and flexible targets. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2008, 48, 1257–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Huang, S.Y. ITScore-NL: An Iterative Knowledge-Based Scoring Function for Nucleic Acid-Ligand Interactions. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 6698–6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimberg, H.; Tiwari, V.S.; Tam, B.; Gur-Arie, L.; Gingold, D.; Polachek, L.; Akabayov, B. Machine learning approaches to optimize small-molecule inhibitors for RNA targeting. J. Cheminform. 2022, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhou, R.; Li, Y.; Li, M. DeepDTAF: A deep learning method to predict protein-ligand binding affinity. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbab072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.R.; Roy, A.; Gromiha, M.M. Reliable method for predicting the binding affinity of RNA-small molecule interactions using machine learning. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbae002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhijian, H.; Yucheng, W.; Song, C.; Tan, Y.S.; Deng, L.; Wu, M. DeepRSMA: A cross-fusion-based deep learning method for RNA–small molecule binding affinity prediction. Bioinformatics 2024, 12, btae678. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, R.; Bernhart, S.H.; Siederdissen, C.H.Z.; Tafer, H.; Flamm, C.; Stadler, P.F.; Hofacker, I.L. ViennaRNA Package 2.0. Algorithms Mol. Biol. 2011, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Bian, J.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Mumtaz, S.; Kong, L.; Xiong, H. Multi-purpose RNA language modelling with motif-aware pretraining and type-guided fine-tuning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2024, 6, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chithrananda, S.; Gabriel, G.; Bharath, R. ChemBERTa: Large-scale self-supervised pretraining for molecular property prediction. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.09885. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, S.R.; Roy, A.; Gromiha, M.M. R-SIM: A database of binding affinities for RNA-small molecule interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 2023, 435, 167914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Zafferani, M.; Akande, O.M.; Hargrove, A.E. Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship (QSAR) Study Predicts Small-Molecule Binding to RNA Structure. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 7262–7277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | RMSE | PCC | SCC |

|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | 0.994 | 0.706 | 0.714 |

| KNN | 1.038 | 0.671 | 0.684 |

| XGBoost | 0.922 | 0.755 | 0.765 |

| GCN | 1.046 | 0.715 | 0.717 |

| GAT | 1.012 | 0.715 | 0.716 |

| Transformer | 1.067 | 0.699 | 0.695 |

| DeepCDA | 0.982 | 0.746 | 0.743 |

| DeepDTAF | 0.957 | 0.751 | 0.747 |

| GraphDTA | 0.928 | 0.772 | 0.773 |

| DeepRSMA | 0.904 | 0.784 | 0.786 |

| MCARSMA | 0.883 | 0.772 | 0.773 |

| Method | RMSE | PCC | SCC |

|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | 1.116 | −0.101 | −0.090 |

| KNN | 1.144 | 0.097 | −0.012 |

| XGBoost | 1.383 | −0.169 | −0.209 |

| GCN | 1.025 | 0.297 | 0.409 |

| GAT | 1.017 | 0.258 | 0.381 |

| Transformer | 0.968 | 0.396 | 0.412 |

| DeepCDA | 1.025 | 0.305 | 0.293 |

| DeepDTAF | 1.106 | 0.077 | 0.052 |

| GraphDTA | 1.012 | 0.301 | 0.316 |

| DeepRSMA | 0.920 | 0.490 | 0.499 |

| MCARSMA | 0.908 | 0.488 | 0.484 |

| RMSE | PCC | SCC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| no-sequence | 0.953 | 0.755 | 0.733 |

| no-structure | 0.971 | 0.751 | 0.731 |

| node-level-only | 0.912 | 0.763 | 0.741 |

| graph-level-only | 0.922 | 0.766 | 0.743 |

| no-interaction | 0.965 | 0.758 | 0.732 |

| complete | 0.883 | 0.772 | 0.773 |

| Model | Train Time/Epoch (s) | Inference Time/Sample (ms) | GPU Memory Peak (MB) | Parameters (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCARSMA (Ours) | 12.3 | 7.25 | 1752 | 7.86 |

| MCARSMA (w/o LM) | 12.1 | 7.11 | 1741 | 7.39 |

| DeepRSMA | 11.8 | 6.41 | 1838 | 3.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, M.; Wang, R.; Wang, X. MCARSMA: A Multi-Level Cross-Modal Attention Fusion Framework for Accurate RNA–Small Molecule Affinity Prediction. Mathematics 2026, 14, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010057

Li Y, Zhang Y, Zhu L, Wang M, Wang R, Wang X. MCARSMA: A Multi-Level Cross-Modal Attention Fusion Framework for Accurate RNA–Small Molecule Affinity Prediction. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010057

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Ye, Yongfeng Zhang, Lei Zhu, Menghua Wang, Rong Wang, and Xiao Wang. 2026. "MCARSMA: A Multi-Level Cross-Modal Attention Fusion Framework for Accurate RNA–Small Molecule Affinity Prediction" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010057

APA StyleLi, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhu, L., Wang, M., Wang, R., & Wang, X. (2026). MCARSMA: A Multi-Level Cross-Modal Attention Fusion Framework for Accurate RNA–Small Molecule Affinity Prediction. Mathematics, 14(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010057