1. Introduction

With the rapid development of computer-aided technologies in the medical field, these intelligent tools provide healthcare professionals with more efficient and precise diagnostic support. The effectiveness of medical image segmentation methods critically influences physicians’ analysis and diagnosis of patient conditions [

1]. Accurate edge segmentation in medical images can clearly distinguish between pathological regions and normal tissues. For example, the segmentation of intestinal polyp images determines the scope of polyp resection: an excessively large resection area may damage healthy intestinal cells, while an insufficient resection may leave potential risks. Therefore, the precision of edge segmentation is particularly crucial in medical image segmentation. However, in many medical images, the edge regions requiring segmentation are often blurred, making it challenging to delineate the segmentation boundaries.

The emergence of U-Net [

2] provided a foundational framework for biomedical image processing. In recent years, numerous methods have focused on improving skip connections from a global perspective to achieve comprehensive fusion of multi-level features. UNet++ [

3] employed a combination of long and short skip connections to aggregate features at each node of the decoder. UNet# [

4] enhanced the restrictive skip connections in UNet++ to enable more flexible and thorough fusion of decoder-extracted features. GLFRNet [

5] proposed global feature reconstruction based on multi-level features from the encoder to capture global contextual information. MSD-Net [

6] introduced a channel-based attention mechanism, utilizing cascaded pyramid convolution blocks for multi-scale spatial context fusion. These methods, which focused on skip connections, aimed to effectively capture long-range dependencies in downsampled feature maps to facilitate the restoration of spatial information during upsampling. However, they often overlooked the challenges posed by blurred edge segmentation. To address this issue, several approaches have been developed: SFA [

7] incorporated an additional decoder dedicated to boundary prediction and employs a boundary-sensitive loss function to leverage region-boundary relationships. This specifically designed loss introduces region-boundary constraints to generate more accurate predictions. Psi-Net [

8] proposed three parallel decoders for contour extraction, mask prediction, and distance map estimation tasks. EA-Net [

9] introduced an edge preservation module that integrates learned boundaries into intermediate layers to enhance segmentation accuracy. Meganet [

10] presented an edge-guided attention module utilizing Laplace operators to emphasize boundary information. Although these methods enhanced the model’s attention to boundaries through explicit boundary-related supervision, they fail to fundamentally improve the model’s inherent capability to autonomously extract comprehensive edge features. As the encoder progressively extracts deeper features, it primarily captures abstract semantic information. Since these approaches do not specifically process the encoder’s shallow features, the edge feature information contained in the early encoding stages remains underutilized.

Vision Transformer [

11] marked a breakthrough by applying Transformer [

12] to image processing, challenging the dominance of traditional convolutional neural networks. TransUnet [

13] replaced the deepest features in the U-Net encoder with features extracted from Vision Transformer. TCRNet [

14] integrated both ViT and CNN as encoders in the segmentation network. Due to the inherent limitations of convolutional operations, CNN-based methods struggle to learn long-range semantic interactions. Consequently, researchers have begun incorporating Transformer technology to enhance skip connections. MCTrans [

15] combined self-attention and cross-attention modules, enabling the model to capture cross-scale contextual dependencies and correspondences between different categories. Swin-UNet [

16] replaced convolutional modules in U-Net with Swin Transformer blocks. DS-TransNet [

17] employed dual Swin-Transformers as the encoder on Swin-Unet’s architecture. PolypFormer [

18] introduced a novel cross-shaped windows self-attention mechanism and integrated it into the Transformer architecture to enhance the semantic understanding of polyp regions. However, the semantic levels and types of information contained in encoder features at different scales are inconsistent, leading to a semantic gap between multi-scale features in conventional Transformer architectures. Consequently, segmentation results from these methods often exhibit satisfactory overall segmentation but coarse edge delineation. Moreover, cross-channel feature fusion Transformers primarily focus on global information integration and fail to effectively address the semantic mismatch between the fused features output by the Transformer and the decoder features.

To address the aforementioned challenges—insufficient extraction of edge features in medical images, dilution of edge information during long-range modeling, and semantic mismatch between cross-channel Transformer outputs and decoder features—this paper proposes a Dual-Path Fusion Network (DPF-Net) based on edge feature enhancement. The contribution of this work can be summarized in four key aspects:

We introduce an Edge Feature Enhancement Gating (EFG) module that effectively aggregates edge features extracted by the early encoder. This strategy not only provides more complete edge features for subsequent inputs but also enhances the model’s robustness in extracting edge features in complex scenarios.

We introduced the Channel-wise Cross-Fusion Transformer (CCT) module with its unique channel cross-attention mechanism, which not only effectively avoids edge dilution in multi-scale fusion but also enables the active enhancement of edge information, shifting from passive transmission to active enhancement.

The proposed Dual-Path Fusion (DPFM) module adopts a two-path strategy: an attention path (with channel and spatial attention) that highlights important edge regions and suppresses background noise, and a weighting path that performs targeted fusion of multi-source features to alleviate semantic gaps.

The proposed DPF-Net is applied to six medical image segmentation tasks on four datasets, including gland segmentation, colon polyp segmentation, and skin lesion segmentation. Compared with other popular methods, DPF-Net has better performance.

2. Method

2.1. Comprehensive Framework

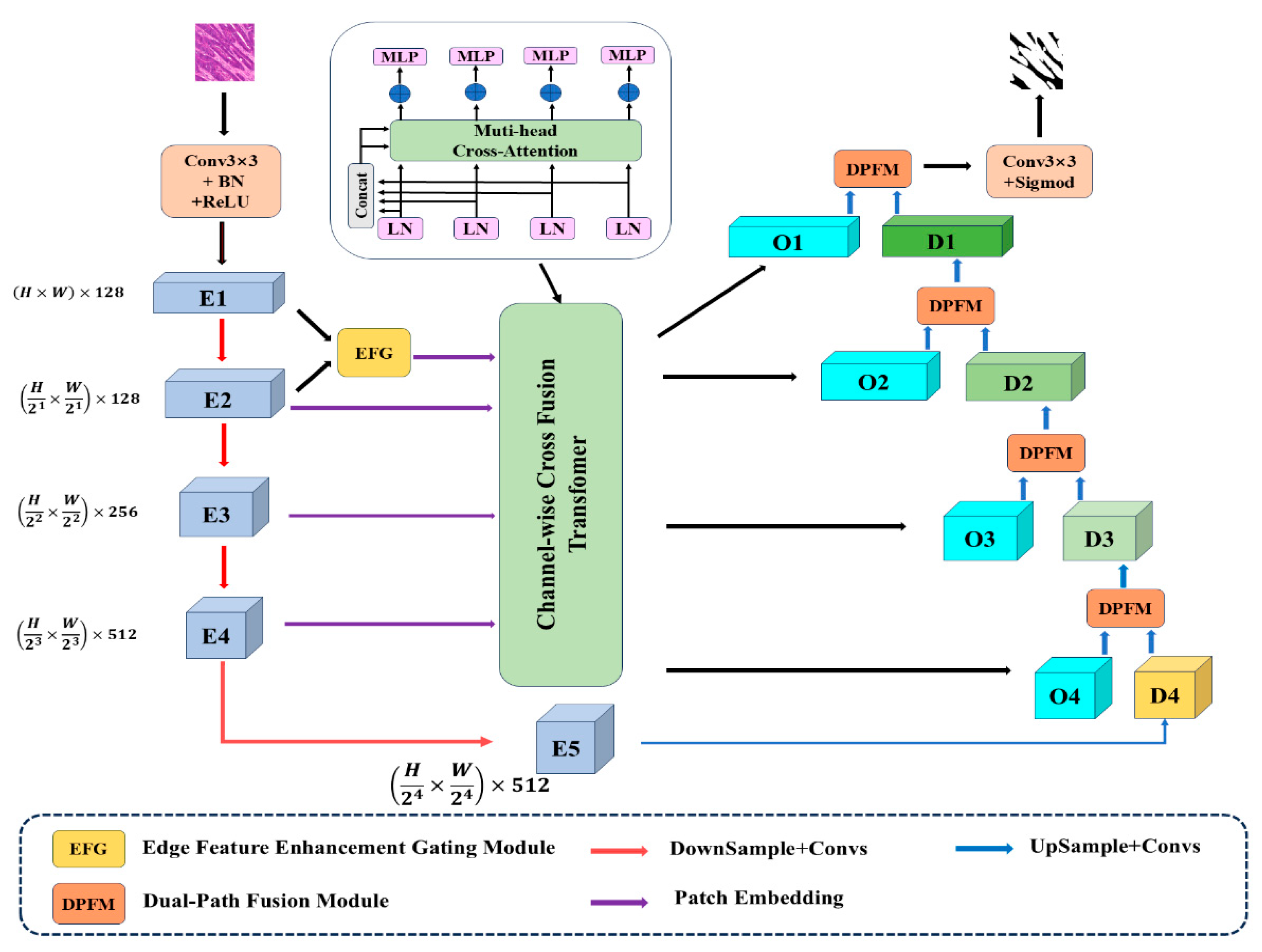

The overall architecture of our proposed network is illustrated in

Figure 1. The input image is first processed through a 3 × 3 convolutional layer, followed by batch normalization and a ReLU activation function, to generate the initial feature map. This feature map then undergoes four successive pooling operations, progressively reducing the spatial resolution while increasing the receptive field, thereby producing the remaining four multi-scale feature maps from the encoder. To capture more comprehensive edge information in the encoder pathway, we incorporate an Edge Feature Enhancement (EFG) Module. This module strengthens the extraction of edge contours in lesion regions by performing weighted fusion of edge features contained in the shallow-level features. The enhanced feature maps from this module, together with the features from the other encoder layers (except the deepest one), are processed through patch embedding and then fed into the Channel-wise Cross-Fusion Transformer (CCFT) module. To emphasize regions of interest and mitigate the semantic gap between the CCFT-processed features and the decoder features, both sets of features are jointly fed into the dual-path decoder. Finally, through upsampling operations, the spatial resolution is progressively restored layer by layer, ultimately yielding the segmented image.

2.2. Edge Feature Fusion Gating (EFG) Module

Due to the often indistinct boundaries between lesion areas and background in medical images, effective extraction of boundary information can significantly enhance segmentation performance. To address this, we propose a gating module that integrates more comprehensive low-level edge features to serve as the first-level features in skip connections. Based on previous studies [

19,

20], early encoder-stage low-level features contain sufficient edge information. Therefore, we integrate two low-level features and adopt a gated fusion strategy [

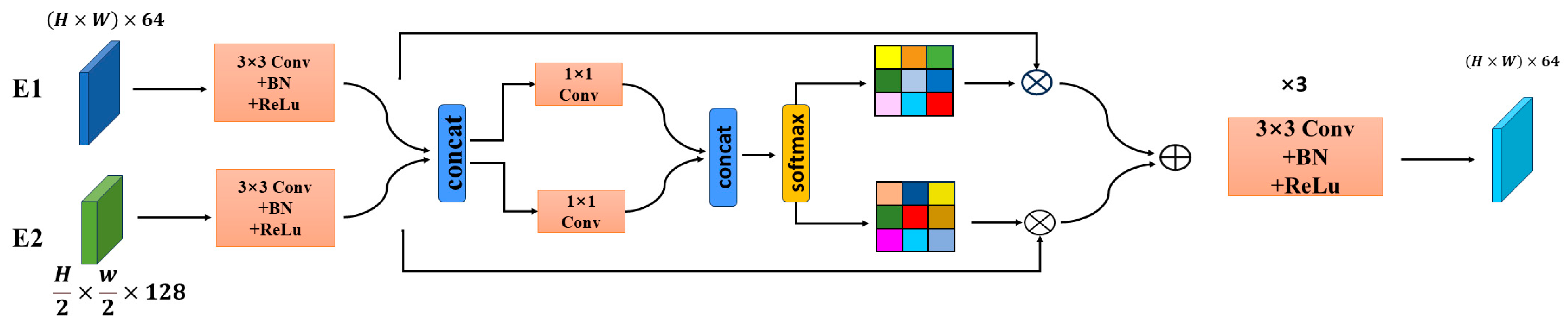

21] to combine them. This gating approach offers the advantage of fusing complementary information from both features to obtain more complete boundary details while adaptively weighting the features to reduce noise interference. The module structure is shown in

Figure 2. First, the first two layers of features obtained from the encoder are concatenated along the channel dimension. Although both sets of encoder features contain edge characteristics, their proportions vary. Therefore, separate gating vectors are created for each feature to independently adjust their respective contributions to the final fused output. This ensures that while edge features are being fused, other detailed features are not neglected. Specifically, the two features are fed into a 3 × 3 convolutional layer followed by batch normalization and an activation function, respectively, to obtain E3 and E4. Subsequently, the two features are concatenated and passed through two separate 1 × 1 convolutional layers to compute the fusion weights. The above processing steps can be formulated as follows:

The operation concat denotes channel-wise concatenation. In order to fully integrate the edge information from the two gating vectors, we further concatenate them to form a new vector G:

A Softmax layer is then applied to obtain a probability distribution along the channel dimension for each position, which is used to weight the different channel feature maps:

Here, the symbol

Gi denotes an element along the channel dimension, and

j represents the index over all channels. The weight extracted for each channel is utilized to perform a weighted fusion of the inputs:

Here, the notation (

i,

j) denotes the weight value corresponding to a pixel. Finally, the two low-level features undergo fusion via the gating mechanism to reduce the fused feature, specifically as follows:

Owing to the sufficient edge information preserved in low-level features, the edge features are assigned greater weights. Thus, the final fused feature map better retains edge details while simultaneously suppressing noise. Finally, the fused features are passed through five convolutional blocks—each consisting of three 3 × 3 kernels followed by one 1 × 1 kernel—to produce the final output feature map with enhanced edge information.

2.3. Channel-Wise Cross-Fusion Transformer (CCFT) Module

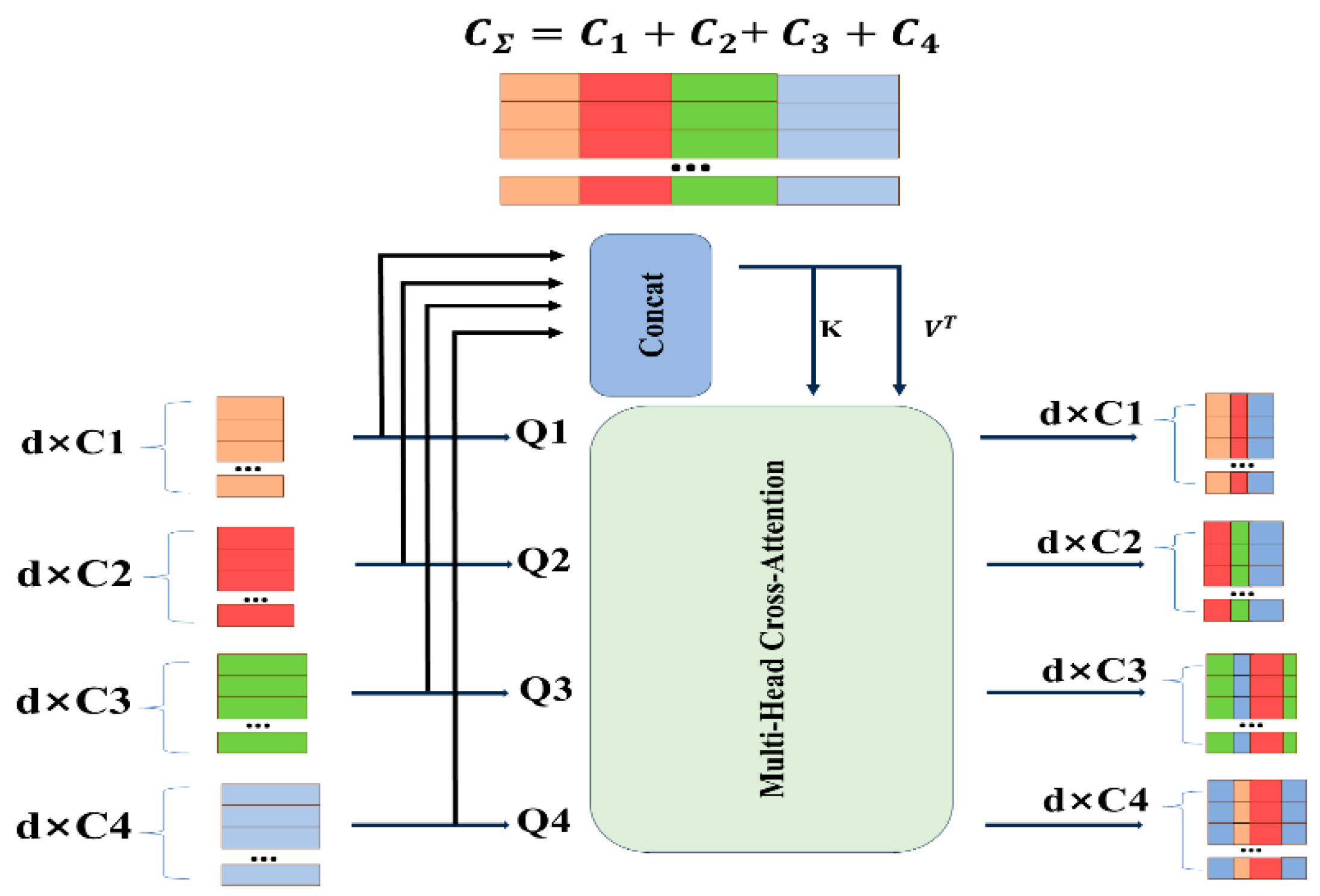

To address the semantic gaps among multi-scale features and obtain comprehensively enhanced features with balanced semantics, while leveraging the strength of Transformers in modeling long-range dependencies, we introduce the Cross-Channel Fusion Transformer (CCFT) module as a feature exchange platform. By employing a cross-attention mechanism along the channel dimension, this module enables features at each encoder level to adaptively select and assimilate information from all other levels—complementing details from shallow layers and semantic context from deep layers. Consequently, it proactively bridges the informational and semantic disparities among different-scale features before they are passed to the decoder.

2.3.1. Multi-Scale Feature Embedding

The four-level encoder feature maps into flattened 2D patch sequences for tokenization, with patch sizes of . These patches are then concatenated along the channel dimension to form tokens . Here, is concatenated as both the key and value, and concatenated as both the key and value to obtain the merged feature map .

2.3.2. Multi-Head Cross-Attention

These tokens are subsequently fed into the Cross-Channel Fusion Transformer module, followed by a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) with residual structure, to encode channel and dependencies for refining features from each U-Net encoder level using multi-scale features. As shown in

Figure 3, the introduced CCFT module contains five inputs: four independent tokens Ti function as query vectors, while the aggregated token

, generated through multi-token concatenation, serves the dual role of both key and value vectors.

here

are weights of different inputs, d is the sequence length (patch numbers) and

are the channel dimensions of the four skip connection layers. In our implementation

. With

, the similarity matrix

is produced and the value V is weighted by

through a cross-attention (CA) mechanism:

where

denote the instance normalization. In the case of N-head attention, the output is computed by applying multi-head cross-attention followed by an MLP with residual operations as follows

Here, N denotes the number of multi-head attention heads. Finally, the four outputs of the L-th layer are reconstructed though an up-sampling operation followed by a convolution layer and concatenated with the decoder features .

2.4. Dual-Path Fusion (DPFM) Module

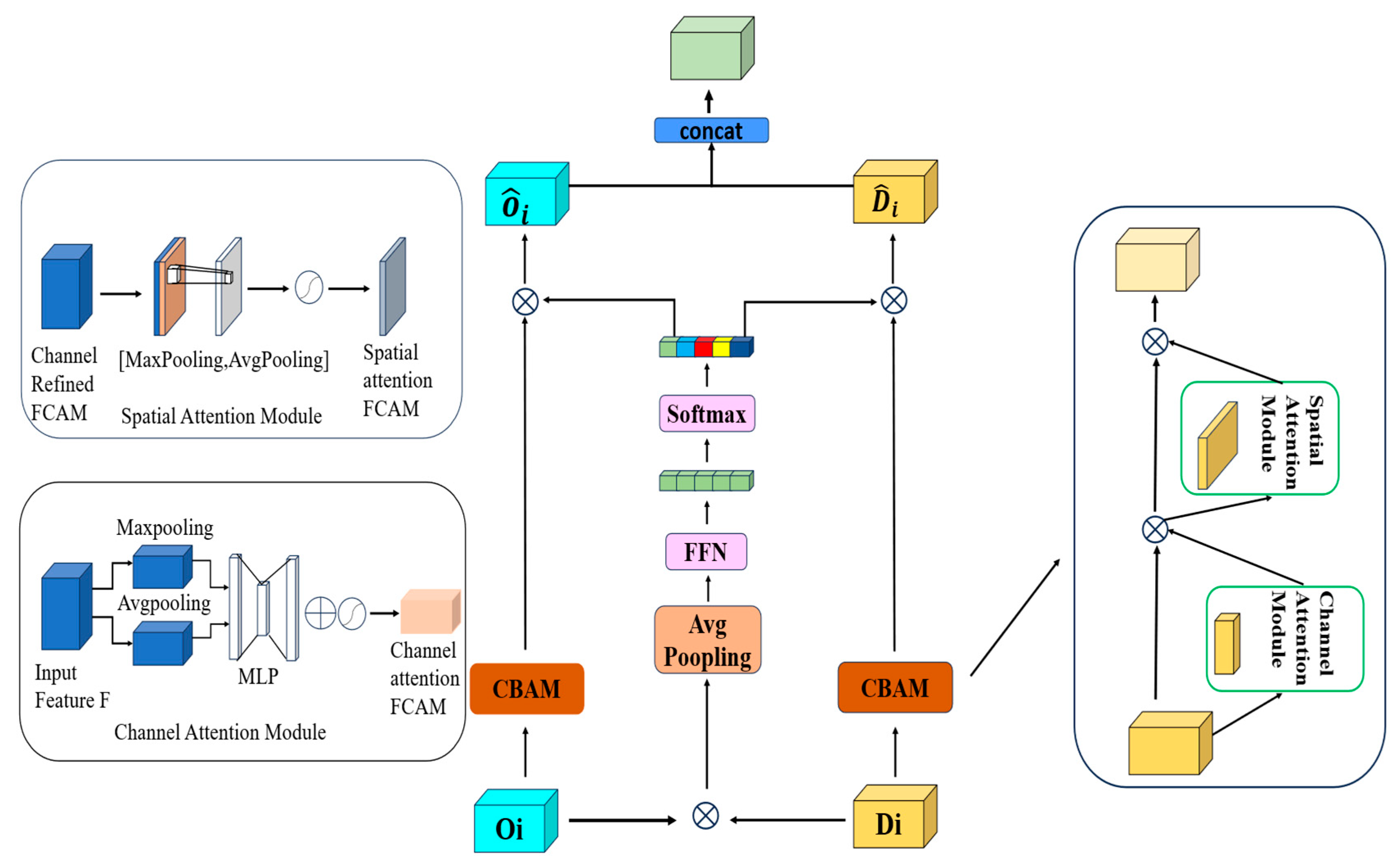

Upsampling serves as a core process in U-shaped networks for restoring spatial resolution and achieving precise localization. However, relying solely on interpolation and convolution operations is insufficient to fully reconstruct the detailed information lost during downsampling. Although skip connections are introduced to supplement these details, significant semantic gaps exist between features processed by the Cross-Channel Fusion Transformer (CCFT) module and those in the upsampling path. To guide channel information filtering, focus on preserving complete edge features, and resolve ambiguities with decoder features, we propose a Dual-Path Fusion Module (DPFM).

The core of this module is an innovative attention fusion mechanism that integrates local detail features from the CNN branch with global contextual representations from the Transformer branch. Each attention path is based on the classical CBAM unit [

22], which consists of a series-connected Channel Attention (CA) and Spatial Attention (SA) structure. The CA module assigns weights to each channel and recalibrates the importance of individual positions to analyze the channel distribution of features. The SA module learns spatial weights and recalibrates the importance of each channel to highlight target objects while suppressing background interference. The weighted path, formed by connecting average pooling, a feed-forward neural network, and Softmax in sequence, dynamically allocates appropriate weights to each branch, thereby reducing semantic disparities between different branches.

Figure 4 illustrates the forward propagation process of the dual-path fusion module. Initially, features from two different sources undergo targeted weighted fusion. By incorporating average pooling, a feed-forward neural network, and Softmax operations, the weighted fusion of features is further enhanced, improving compatibility during the integration of the two branch features:

2.5. Loss Function

We employed a combined loss function consisting of both Cross-Entropy and Dice loss, which enables the model to achieve precise pixel-level classification while simultaneously optimizing the quality of the segmented regions. The loss function is defined as follows:

where α denotes the weighting coefficient for the Dice loss, which is set to 0.5 in our experiments,

represents the ground truth label,

is the predicted value, and

signifies the predicted probability.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Comparison

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 present the comparative evaluation results between our proposed method and baseline approaches across multiple metrics, with bold values indicating the best performance.

As detailed in

Table 3, our network achieves Dice and IoU scores of 80.50%/91.90% on the MoNuSeg dataset and 67.54%/85.48% on the GlaS colorectal gland dataset, representing improvements of 0.97%/0.62% and 0.68%/0.48%, respectively, over the compared methods. Additionally, our method maintains a relatively lower parameter count compared to the listed CNN-Transformer hybrid approaches.

Table 4 demonstrates that our method attains Dice and IoU values of 86.47%/78.36% on ISIC-2017 and 88.87%/81.79% on ISIC-2018, corresponding to performance gains of 0.82%/0.71% and 1.00%/1.22%, respectively, in skin lesion segmentation.

The results in

Table 5 show our network achieving 90.62%/84.23% on Kvasir and 92.14%/87.01% on CVC-ClinicDB for colon polyp segmentation, with respective improvements of 0.97%/0.69% and 0.80%/1.84% over existing approaches.

These experimental findings substantiate that our proposed network not only significantly enhances medical image segmentation accuracy but also maintains consistent performance gains across diverse dataset types, confirming its robust generalization capability.

Furthermore, our method maintains a parameter count that is comparatively lower than other CNN-Transformer hybrid approaches cited in the comparison.

4.2. Qualitative Comparison

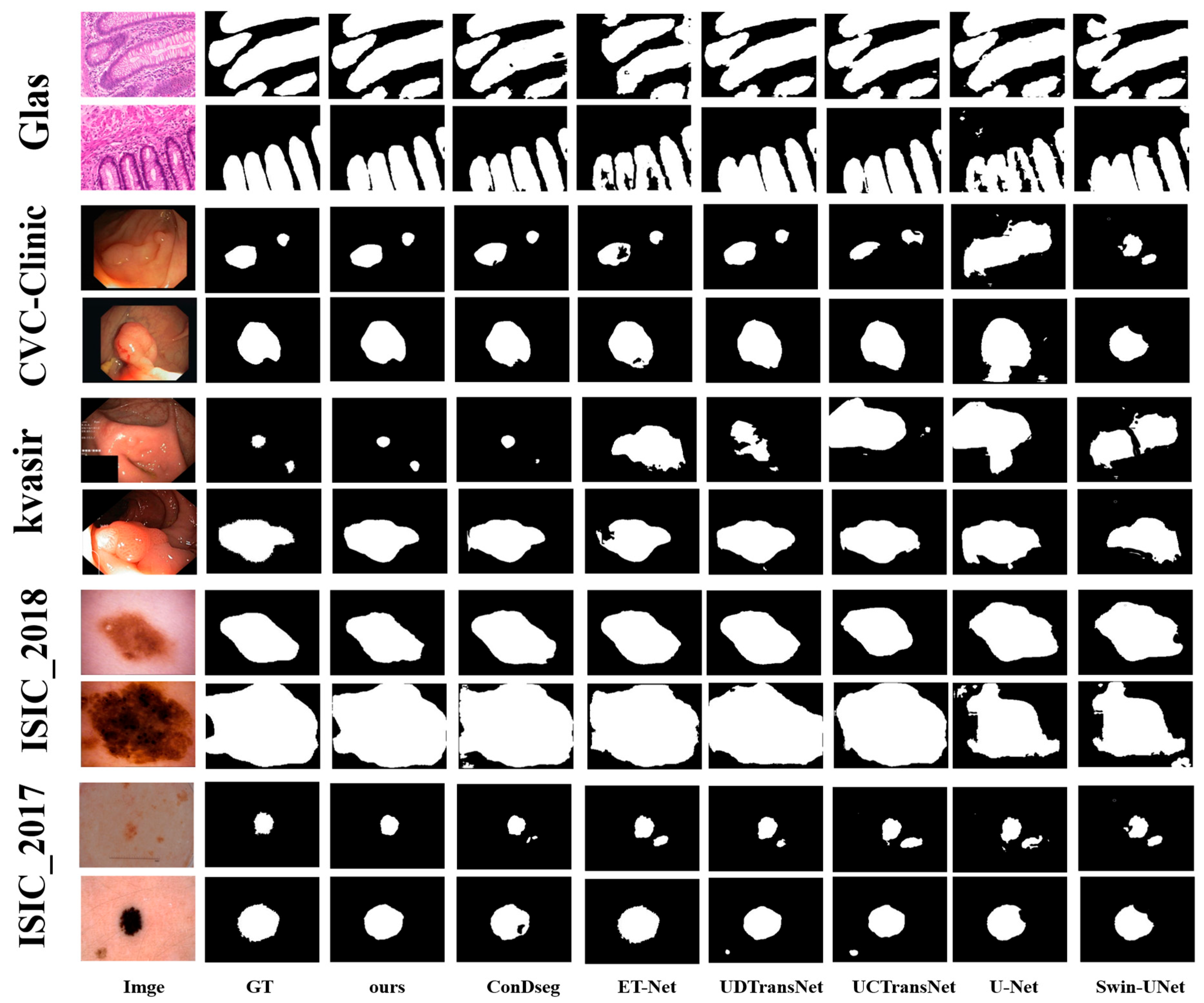

To validate the effectiveness of our proposed network architecture, we conducted comparative experiments with five methods: the classical U-Net, three edge-enhanced algorithms primarily based on CNN architecture (ET-Net, MEGANet and ConDseg-Net), and four general segmentation algorithms combining CNN and Transformer architectures (Swin-UNet, FUSION-UNet, UCTransNet, and UDTransNet).

For each dataset, we selected two types of images: the first row contains images with indistinct lesion boundaries and low environmental contrast, while the second row presents images with relatively clear lesion edges and high environmental contrast. As shown in

Figure 5, the first row of each dataset displays the first type, and the second row shows the second type. From the results, we observe that ET-Net and ConDseg-Net demonstrate advantages over Swin-UNet, UCTransNet, and UDTransNet in segmenting low-contrast images. Their superior focus on edge features enables them to delineate contours in such environments, rarely resulting in over-segmentation. In contrast, the three Transformer-based networks, focusing on global multi-level feature fusion, tend to overlook edge details. This leads to over-segmentation when processing low-contrast images with ambiguous lesion boundaries. For high-contrast images, UCTransNet and UDTransNet, despite occasional boundary-related over-segmentation, outperform ET-Net and ConDseg-Net in lesion region segmentation. This advantage stems from the Transformer architecture’s strength in long-range dependency modeling, capturing remote semantic information through a global perspective and achieving more complete segmentation areas via multi-level fusion. Conversely, ET-Net and ConDseg-Net, lacking such long-range modeling capabilities, exhibit incomplete segmentation regions. U-Net, with its basic encoder–decoder structure and simple skip connections, demonstrates the weakest performance among all compared methods.

Our proposed model integrates an Edge Feature Enhancement Gating (EFG) Module to capture more complete edge features, combines a Cross-Channel Fusion Transformer (CCFT) module to leverage long-range modeling for remote semantic information, and finally incorporates a Dual-Path Fusion (DPFM) module to emphasize critical features (including edge features) while reducing semantic gaps. As illustrated in the figure, our network produces segmentation results with both clear boundaries and complete regions, confirming the effectiveness of our approach.

4.3. Ablation Study

4.3.1. Analysis of Hyperparameter Settings

To identify the optimal hyperparameter configurations for our experimental setup, we conducted a series of systematic experiments across three distinct datasets: GlaS, ISIC2018, and Kvasir. We initially set the α value to the default of α = β = 0.5, a common and reasonable strategy to maintain balanced contributions from both loss terms and prevent either from dominating the optimization process. Furthermore, since the boundary enhancement module in our model can acquire relatively sufficient edge features, increasing the weight of α is not suitable. As shown in

Table 6, fine-tuning the α value leads to decreased accuracy, confirming our choice of α = 0.5. Regarding the configuration of heads (H) and layers (L) in our CCFT module, these parameters were empirically initialized based on optimal values from UCTtranNet. Experimental results demonstrate that reducing the value of L does not negatively impact performance and even slightly improves segmentation accuracy. However, simultaneously decreasing both L and H values causes noticeable performance degradation. Therefore, we ultimately set H = 4 and L = 2.

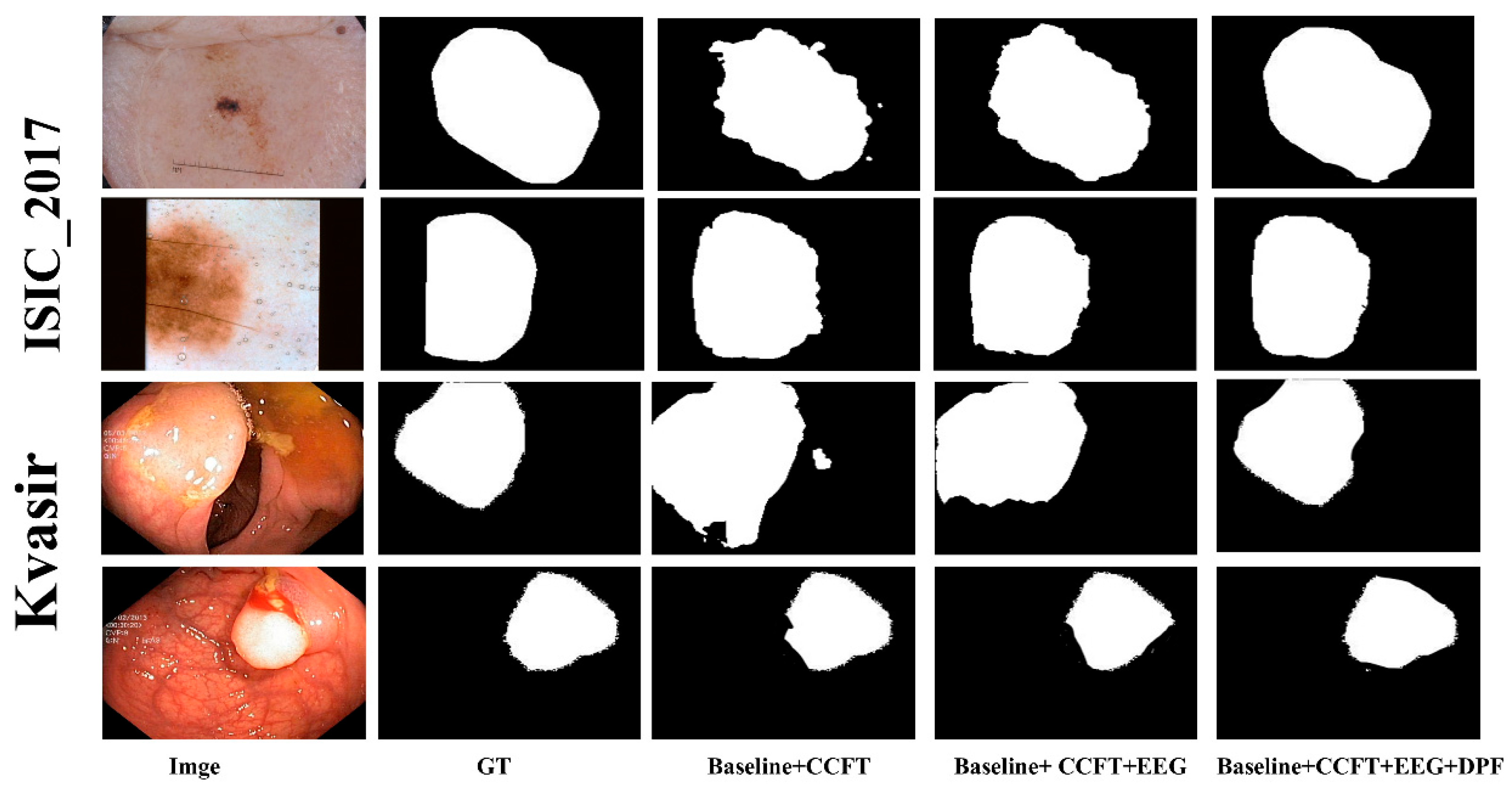

4.3.2. Comparison with Baselines

To validate the effectiveness of each component in our proposed algorithm, ablation studies were conducted on five datasets: GlaS, ISIC2017, ISIC2018, CVC-ClinicDB, and Kvasir. The U-Net architecture was adopted as our baseline model. We incrementally incorporated key components—the Cross-channel Fusion Transformer module, the Edge Feature Enhancement Gating module, and the Dual-path Fusion module—to evaluate their individual and combined impact on segmentation performance. As shown in

Table 7, both the Dice and IoU metrics improved progressively with the addition of each key component. Furthermore, representative samples from two types of datasets were selected for visual analysis, as illustrated in

Figure 6. Consistent with the selection criteria used in the segmentation result visualization, we included both high-contrast and low-contrast images from each dataset category. It can be observed that, regardless of whether the input image exhibits high or low environmental contrast, the segmentation results demonstrate noticeable enhancement in both boundary delineation and overall region consistency as each proposed module is successively integrated. These experimental results confirm that every module contributes positively to the performance. The sequential integration strategy not only effectively enhances the capability of boundary extraction and segmentation accuracy but also enables the network to segment medical images with higher precision.

5. Conclusions

To address the limitations of existing segmentation methods, this paper proposes a novel edge feature-enhanced dual-path fusion network for image segmentation. By incorporating an edge feature enhancement gating module, the model effectively captures comprehensive edge features from the early encoder stages, thereby providing richer edge information for subsequent feature fusion while significantly improving the model’s robustness in segmenting images with blurred boundaries. During the feature fusion stage, the multi-level features processed by the cross-channel fusion Transformer module, along with the corresponding decoder features, are fed into the dual-path fusion module. This module employs a dual-path design: the attention path enhances critical regions and suppresses background interference through channel and spatial attention mechanisms, effectively preventing the dilution of edge features in deep layers; the weighting path achieves precise fusion of multi-source features via adaptive weight allocation, significantly bridging the semantic gap. Ultimately, the synergistic combination of dual-path output and upsampling operations enables fine restoration of spatial resolution, resulting in more accurate segmentation outcomes. Experiments on six public datasets demonstrate that the proposed network exhibits exceptional capability in capturing complex boundary structures across various segmentation tasks, along with remarkable generalization performance. The method holds significant potential for early clinical practice and pathological analysis, providing reliable technical support for automated lesion detection, precise lesion measurement, and early disease diagnosis.

However, this study still has certain limitations. The adoption of Transformer architecture for skip connections considerably increases the model parameter count, leading to reduced computational efficiency. Therefore, developing lightweight models to improve the efficiency of medical image segmentation will be a key focus of our future research.