1. Introduction

The accelerating global climate crisis has brought corporate green innovation to the forefront of strategies for reconciling economic growth with environmental sustainability. Yet, despite its strategic importance, firms continue to underinvest in green innovation because it embodies a double externality: environmental benefits that diffuse broadly to society and knowledge spillovers that competitors can freely appropriate [

1,

2,

3]. Double externalities reduce firms’ ability to capture private returns while exposing them to higher risks and uncertainties, thereby weakening incentives to invest in long-term green innovation [

4]. These dynamics suggest that firms alone are unlikely to sustain the level of innovation required to meet societal demands. Against this backdrop, institutional investors have emerged as pivotal governance actors, as their concentrated ownership, active engagement, and long-term orientation enable them to influence managerial decisions and help mitigate the distortions created by unpriced externalities [

5,

6]. Understanding how institutional investors address the dual externalities of green innovation is essential for advancing both theory and practice in sustainable development.

Existing literature establishes two critical consensus points. First, institutional investors enhance corporate governance through active monitoring and engagement, mitigating agency costs and aligning management incentives with long-term value creation [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Second, green innovation is increasingly recognized as a strategic imperative where private returns intersect with public goods, necessitating alignment between firm-level incentives and societal environmental goals [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Rennings (2000) categorized the antecedents of green innovation into three types: technology push, market pull, and regulation push or pull [

2]. Government policies that internalize environmental or knowledge spillover externalities enhance the ability of institutional investors to promote corporate green innovation [

2,

15]. By reducing regulatory uncertainty and aligning financial returns with sustainability goals, such policies amplify institutional investors’ influence in steering firms toward greener R&D investments [

16,

17]. This synergistic effect underscores the importance of cohesive environmental governance and investor stewardship in accelerating the low-carbon transition [

18]. These foundations imply that institutional investors’ influence on green innovation should logically intensify when governments ensure the internalization of environmental and knowledge spillover externalities [

18,

19].

Moreover, the double externalities of green innovation have long been theorized to suppress green innovation absent policy interventions [

2,

11]. Simultaneously, institutional investors are posited to amplify governance quality where government supports, or regulatory infrastructures are robust [

5,

18]. In addition, when environmental benefits or knowledge spillovers are not internalized, firms face a “tragedy of the commons” [

20], dampening investment incentives. Thus, a natural synthesis predicts that institutional investors’ pro-green impact peaks when externalities are internalized through affluent government subsidies, stringent environmental regulations, or intellectual property protection (IPP).

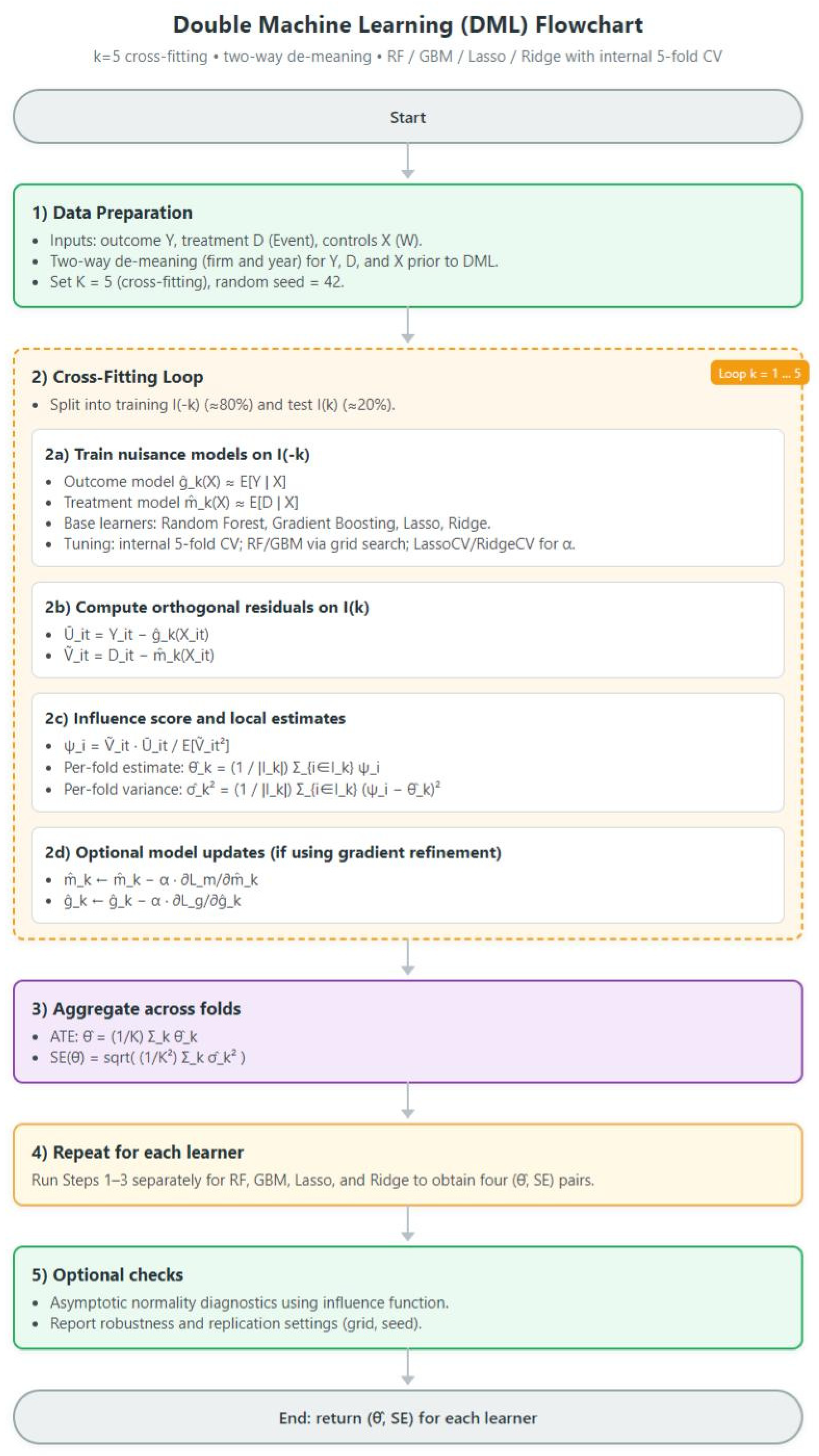

We analyze the effect of institutional investors on firms’ green innovation under the challenge of double externalities, emphasizing whether their impact intensifies when formal mechanisms of externality internalization are weak. Formally, we estimate a firm- and year-fixed effects Poisson model as the baseline specification and then extend the analysis using a double machine learning framework. The DML procedure combines cross-fitting with flexible learners—including random forest, gradient boosting, Lasso, and Ridge—to approximate high-dimensional nuisance functions m and g, thereby satisfying Neyman-orthogonality conditions. This design enables us to capture both linear and nonlinear structures in the data, reduce bias from high-dimensional confounders, and rigorously test whether institutional investors act as substitutes for incomplete institutional arrangements.

Contrary to the conventional prediction that stronger internalization of externalities should amplify investor influence, our results indicate that institutional ownership is more strongly associated with green innovation output under low government environmental subsidies or lax IPP regimes. Such findings suggest that institutional investors act as substitutes for weak externality internalization. To interpret this paradox, we situate the analysis in China’s economic transition and draw on insights from new institutional economics (NIE). China’s transition was marked by reforms that reshaped capital markets [

21]. For example, the split-share reform expanded institutional ownership by enabling institutions to hold stock options previously off-limits, which in turn strengthened managerial oversight and provided buffers against risks in R&D experimentation [

22,

23]. As Menard et al. (2021) emphasize, macro institutions establish foundational regulations that shape the functioning of micro-level institutional arrangements, such as firm-level governance [

24].

Our study contributes to the corporate governance and green innovation literature as well as to the co-evolutionary perspective in transitional economies [

25]. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to show that institutional investors can substitute for weak externality internalization, challenging the expectation that more externalities necessarily suppress investment incentives [

2]. While prior works emphasize ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) stewardship and impact investing [

6,

18], this study advances the debate by conceptualizing institutional investors as compensatory governors that internalize environmental and knowledge externalities through governance and ownership. Drawing on new institutional economics, we argue that institutional investors reduce transaction costs and clarify property rights in weak institutional environments, thus enhancing firms’ incentives for green innovation [

26]. This integration positions institutional investors not merely as financiers [

10], but as active institutional mechanisms in the green transition process. Second, by combining fixed-effects econometric estimation with double machine learning, our study provides a more comprehensive empirical strategy to uncover the paradox of stronger influence under market failures. We further highlight transparency as a compensatory governance mechanism, thereby recasting institutional investors from passive monitors to active architects of disclosure regimes. Third, we enrich the theoretical understanding of informal institutions in transitional economies by demonstrating how formal market reforms interact with informal institutions to shape environmental governance, echoing the NIE argument that institutions reduce transaction costs by aligning incentives [

27,

28].

Our findings hold critical lessons for policymakers navigating sustainability transitions in emerging markets. Rather than delaying green reforms until externality pricing mechanisms mature, regulators can strategically empower institutional investors through disclosure mandates to amplify transparency’s governance role and through stewardship incentives to align investor horizons with environmental goals.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

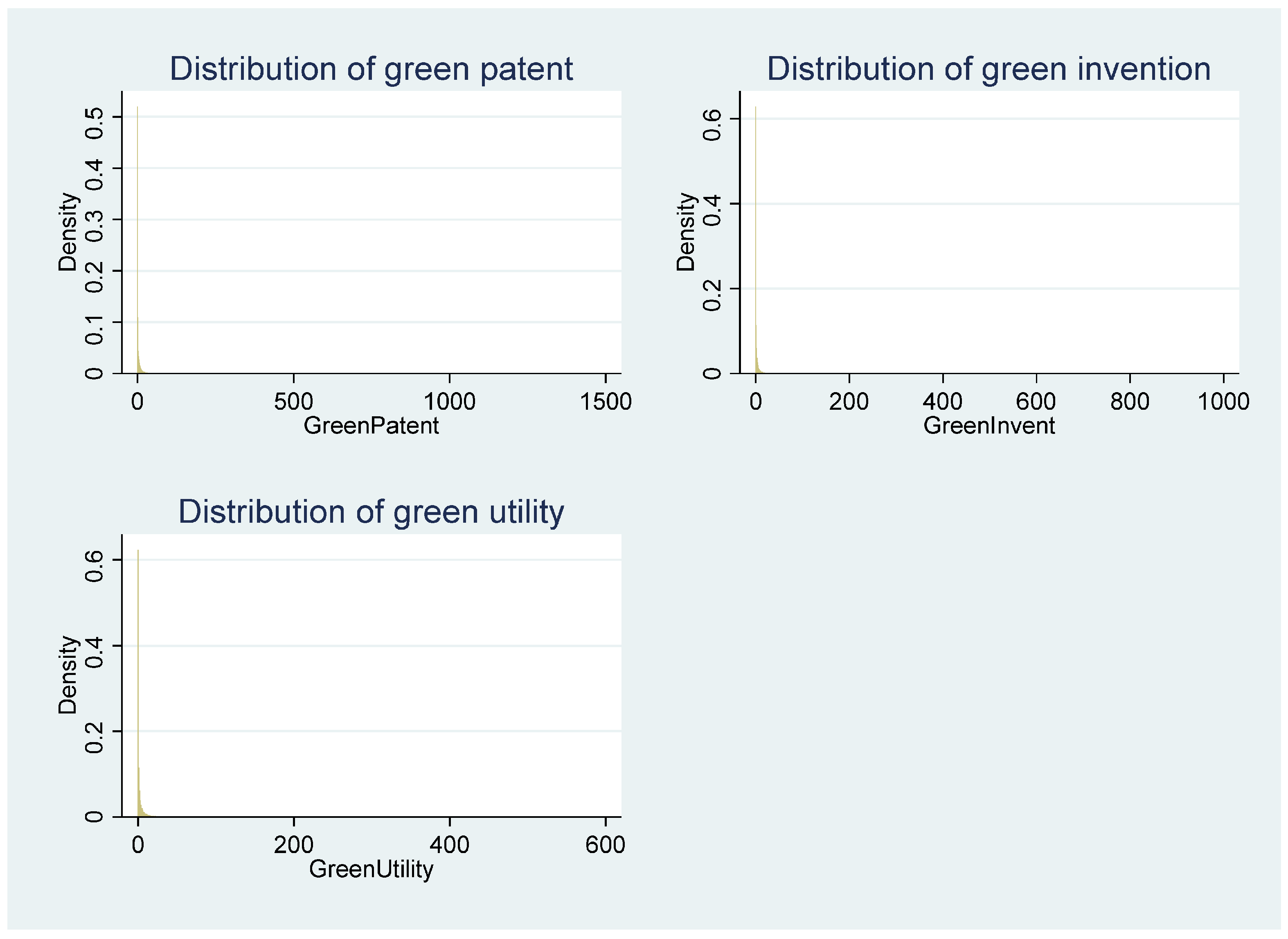

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics. The summary shows that the green patent application average at 7.374, while the max value and standard deviation are 1485 and 38.258, respectively. This indicates considerable differences in green innovation among firms. The mean of institutional ownership is 0.432, with a paramount of 0.938 and a standard deviation of 0.253, implying differences in institutional ownership level among Chinese listed companies. In addition, the proportion of zero observations is 52% for GreenPatent, 62.9% for GreenInvent, and 62.4% for GreenUtility.

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of green innovation.

To examine variable correlations and assess multicollinearity of the variables, our study presents Pearson correlations in

Table 3. The significantly positive correlation coefficients at 1% level for institutional ownership indicates institutional investor is positively correlated with both green patent and green invention. This provides preliminary support for Hypothesis 1. Furthermore, the coefficients between controls exhibit beneath 0.5, and the variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis yields an average VIF of 1.33, indicating that the absence of multicollinearity among variables.

4.2. Results of Fixed-Effects Regression

We start with Poisson regressions to quantitatively estimate the influence of institutional ownership on corporate green innovation. In

Table 4, the regression outcomes corresponding to Equation (1) are presented. In addition,

Supplementary Material Figure S1 shows the path of the fixed effects coefficients for each year.

The estimated coefficients for institutional ownership in columns (1) and (2) of

Table 4, 0.372 and 0.554, indicate that a 10% increase in institutional ownership leads to 0.0372 more green innovation quantity (GreenPatent) while the same increase leads to 0.0554 more green innovation quality (GreenInvent). For instance, using the mean and standard deviation of institutional ownership, a one-standard-deviation increase in institutional ownership corresponds to approximately a 6.8% rise in green patent applications and a 5.2% improvement in green patent quality. On the contrary, column (3) suggests the absence of a significant association between institutional investors and green utility innovation—the estimate is small and insignificant. Consistent with our expectations, the numbers in columns (1) and (2) of

Table 4 reveal that institutional ownership exhibits a positive relationship relative to green innovation. This effect can be attributed to two reasons. First, institutional investors alleviate firms’ apprehensions regarding the positive externalities of green innovation, incentivizing managerial commitment to long-term sustainability investments that may lack immediate financial returns. Second, their stewardship enhances information transparency, enabling firms to credibly signal ESG alignment and mobilize complementary resources through strategic collaborations with eco-conscious stakeholders.

4.3. Results of Double Machine Learning

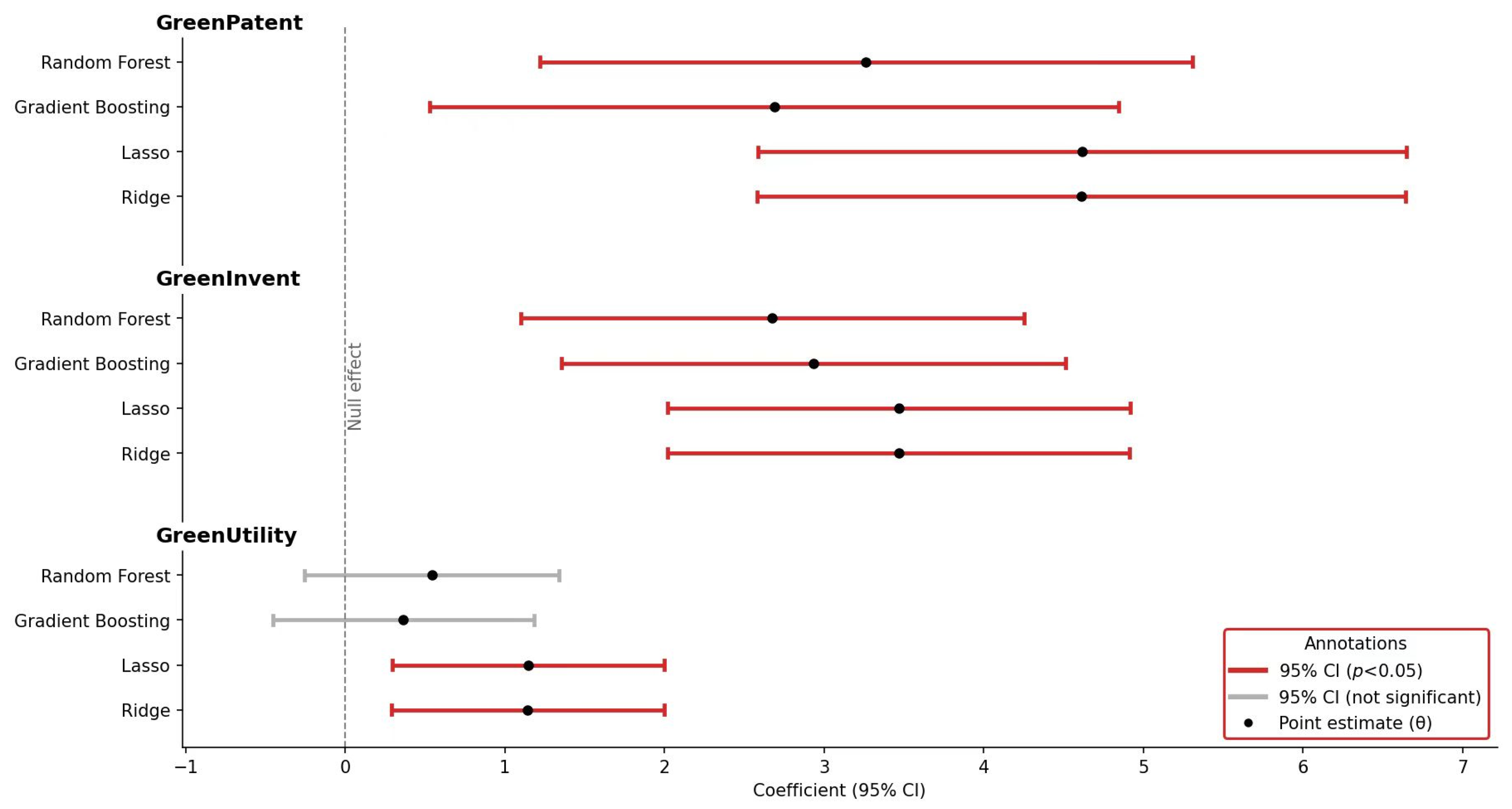

The double machine learning estimations reported in

Table 5 and

Table 6 provide consistent evidence that institutional investors significantly promote corporate green innovation. In

Table 5, both random forest and gradient boosting yield positive and significant coefficients for green patents and green invention patents. For instance, the coefficient of institutional ownership on green patents is 3.262 under the random forest model and 2.689 under gradient boosting, both statistically significant. Similarly, the effect on green invention patents is 2.676 and 2.934, respectively, indicating that institutional investors foster not only the expansion of overall green patenting but also the generation of more technologically sophisticated inventions.

Table 6 reports the results based on Lasso and Ridge regression, which provide further robustness checks with regularized estimation techniques. The findings are again consistent: institutional ownership has strong and highly significant effects on both green patents and green invention patents, with coefficients of 4.618 and 3.469 in the Lasso model, and 4.612 and 3.468 in the Ridge model, all significant at the 1% level. These results reinforce the conclusion that institutional investors are crucial drivers of green innovation. Interestingly, for green utility models, Lasso and Ridge estimations reveal positive and significant effects (coefficients of 1.148 and 1.144, respectively), in contrast to the insignificant results in

Table 5. This divergence highlights that while institutional investors’ strongest influence lies in promoting high-value, invention-oriented green innovation, they may also indirectly support more incremental innovation activities when evaluated under linear regularization methods [

77].

Taken together, the results across

Table 5 and

Table 6 demonstrate the robustness of our findings to different machine learning algorithms. The consistency of positive and significant effects on green patents and green invention patents underscores the role of institutional investors as compensatory governors in the face of weak externality internalization. Moreover, the nuanced differences observed for green utility models reveal that investors’ influence is not uniform across innovation types, but instead reflects a long-term orientation toward supporting innovation activities that are more likely to deliver sustainable competitive advantage and environmental benefits.

Fixed-effects regressions remain the gold standard for identifying within-firm variation and controlling for unobserved heterogeneity across firms and over time. However, such models may be limited in capturing high-dimensional, nonlinear relationships between covariates and outcomes. By employing double machine learning (DML) with algorithms such as random forest, gradient boosting, Lasso, and Ridge, we mitigate these limitations and provide a robustness check that flexibly accounts for complex interactions among firm characteristics, ownership structures, and institutional environments. This approach is particularly well suited for research on green innovation, where drivers are inherently multifaceted and nonlinear [

73,

78]. The consistency of our findings across econometric and machine learning estimators increases confidence that the observed effects are not artifacts of model specification but reflect genuine causal relationships.

Figure 3 visualizes the estimated coefficients and 95% confidence intervals from the four machine learning estimators, complementing the regression results presented in

Table 5 and

Table 6. For both green patents and green invention patents, the coefficients are consistently positive and statistically significant across all models. Random forest and gradient boosting, reported in

Table 5, generate coefficients around 2.5–3.0, while Lasso and Ridge regressions, reported in

Table 6, yield even larger effects exceeding 4.0 for green patents and around 3.5 for green invention patents. The relatively narrow confidence intervals in

Figure 3 underscore the robustness of these findings and highlight that institutional investors exert a substantial and reliable positive influence on both the volume and the quality of green innovation [

2].

By contrast, the results for green utility models display greater heterogeneity across methods. As shown in both

Table 5 and

Figure 3, random forest and gradient boosting produce coefficients that are close to zero with wide confidence intervals, indicating no systematic effect. In

Table 6, however, the Lasso and Ridge estimations align with

Figure 3 by showing positive and statistically significant coefficients of approximately 1.1, with narrower confidence intervals. This divergence across algorithms illustrates the methodological complementarity of nonparametric and regularized estimators: while tree-based methods may attenuate weaker innovation signals, penalized linear models emphasize more stable incremental effects. Taken together,

Figure 3 and

Table 5 and

Table 6 demonstrate that institutional investors’ strongest impact is concentrated on high-value innovation outcomes—green patents and inventions—while their influence on utility models remains more modest and method-dependent [

73].

It is important to note that the purpose of employing multiple machine learning algorithms is not to select a single “best” model, but rather to demonstrate the robustness of our core finding. The slight variations in the coefficient magnitudes across models reflect the different ways each algorithm approximates the underlying nuisance functions; for instance, tree-based models excel at capturing non-linear interactions, while regularized linear models are efficient in high-dimensional settings with potentially sparse signals. The consistent direction and statistical significance of the InstInvest coefficient across all four distinct learners strongly suggest that the positive causal relationship with green innovation is a robust feature of the data, not an artifact of a particular model specification.

4.4. Endogeneity Tests

While the baseline regression results confirm a significant positive correlation between institutional ownership and corporate green innovation, these findings may be subject to endogeneity concerns. On the one hand, unobserved factors that simultaneously affect both institutional investors’ asset allocation decisions and corporate green innovation could introduce endogeneity. On the other hand, institutional investors, guided by their asset allocation strategies, might proactively select and hold firms that already exhibit strong performance in green innovation to reap higher short-term profits. This behavior suggests a sample selection bias as well as reverse causality, as the positive relationship may not stem from the influence of institutional ownership on corporate decisions but rather from the initial choice of firms. To avoid endogeneity, this study employs two-stage least squares (2SLS) and Heckman two-step regression to correct for omitted variable bias, reverse causality and sample selection bias.

4.4.1. Two-Stage Least Squares Model

To attain consistent estimates of the relationship between institutional ownership and green innovation and mitigate potential biases due to unobserved factors and reverse causality, we employ 2SLS with two instrumental variables (IVs). The first is a binary variable representing the changes whether a firm is included in the CSI 500 Index (In500): In500 equal to 1 if a firm’s stock moved from outside to inside the index in the previous period and 0 otherwise. The second IV is the attention from security analyst specializing in the industry of the focal firms (Analyst). Analyst is the number of analysts in the securities company who have published research reports in the year. These two IVs satisfy the relevance principle: when a firm becomes part of the index, it tends to attract index-tracking and passive institutional funds, thereby increasing institutional ownership [

79,

80]; analysts closely monitor companies within the same industry, and their reports and recommendations have a substantial impact on institutional investor interest and decisions [

81]. Meanwhile, these two share variables are not directly related to corporate green innovation, satisfying the exclusion principle of IV.

In column (1) of

Table 7, both coefficients of In500 and Analyst are significantly positive in the first-stage regression. The second-stage regression results in column (2) and (3) verify the baseline results are reliable. Moreover, the Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic is significant at the level of 1%, which can reject the hypothesis of insufficient identification of instrumental variable. The weak instrumental variable test shows that both the Kleibergen-Paap rk Wald and Cragg-Donald Wald F statistics are greater than 19.93, rejecting the null hypothesis of weak IV at 1% level. The robust weak identification test, conducted with Anderson-Rubin Wald test, rejects the null hypothesis that the sum of the endogenous regression coefficients is zero at 1% level, which further supports the strong relevance of the IVs and institutional ownership. The Hansen J-statistic fails to reject the null hypothesis, suggesting that there are no issues with overidentification.

4.4.2. Heckman Two-Stage Model

To address the potential issue of sample selection bias, this study employs the Heckman two-step regression model. In the first stage, we transform the independent variable into a dummy variable of institutional investors. This variable is coded as 1 if a firm’s institutional ownership is above the median of the distribution of the sample in the current year, and 0 otherwise. Following this, we construct a Probit regression model of

on the control variables employed in regression (1) to calculate the inverse Mills ratio (IMR). In the second stage, we include the IMR obtained from the first stage as a control variable in the benchmark regression model to test the effect of possible selection bias on the research conclusion. We report the results of the second stage in

Table 8.

The results in

Table 8 indicate that the IMR is significant in the two regressions, which suggests that the baseline regression results are indeed subject to endogeneity issues arising from sample selection bias. Therefore, it is necessary to control for this bias using the Heckman two-step regression. Unsurprisingly, the coefficients of the institutional ownership remain significantly positive at the 5% level for green patent and at the 1% level for green invention, indicating that the baseline regression results are robust and the conclusions hold after accounting for sample selection bias.

4.4.3. GMM Test

The dynamic GMM estimations presented in

Table 9 highlight a significant and persistent influence of institutional investors on corporate green innovation. Across specifications, the coefficient of InstInvest is positive and statistically significant for both green invention patents and overall green patents, suggesting that firms with higher institutional ownership exhibit stronger incentives to engage in environmentally oriented innovation. This finding aligns with the view that institutional investors act as effective governance agents who reduce information asymmetry and encourage long-term, sustainability-driven R&D strategies.

The lagged dependent variables are also positive and significant, confirming the path-dependent and cumulative nature of green innovation—firms with past innovation records tend to maintain or expand such efforts. Diagnostic tests validate the reliability of the GMM specification: the Arellano–Bond AR (1) test indicates expected first-order autocorrelation, while AR (2) fails to reject the null of no second-order autocorrelation, and both Sargan and Hansen tests confirm instrument validity. Overall, these results provide strong empirical evidence that institutional investors play a sustained and catalytic role in promoting firms’ green innovation capacity.

4.5. Robustness Tests

4.5.1. Alternative Measure of Green Innovation

To enhance the robustness of our results, we use the number of a corporate’s authorized green patents as an alternative measure of green innovation quantity and the number of authorized green inventions as an alternative proxy for green innovation quality. The results, presented in columns (1) and (2) of

Table 10, show that the coefficients for institutional ownership are both significantly positive in both models, further supporting the robustness of our main findings.

4.5.2. High-Dimensional Fixed Effects and Standard Error Assumptions

Although the benchmark regressions controlled for year and individual fixed effects, the results might vary due to different regions and industries. This paper further control for city and industry fixed effects. The results in column (3) and (4) of

Table 10 show that institutional investors significantly enhance green innovation after controlling for year, firm, city and industry fixed effects, indicating that the findings are robust. Furthermore, we controlled for joint fixed effects, including industry-year and region-year interaction fixed effects. See

Supplementary Material Tables S2 and S3 for details.

4.5.3. Zero-Inflated Poisson Estimation

Furthermore, we conduct a robustness check by applying the zero-inflated Poisson model, which jointly models both the zeros and the nonzero counts. Column (5) and (6) of

Table 10 present that zero-inflated Poisson regression results on the associations between institutional ownership and both types of green innovation are significantly positive. This is consistent with the baseline results.

4.6. Driving Role of “Double Externalities” and Mechanism Analysis

The preceding analysis has established that institutional ownership exerts a significant positive influence on corporate green innovation, attributable to their capacity to rectify the “dual externalities” of environmental protection and knowledge spillovers. Our theoretical analysis posits that when the positive environmental externalities of corporate green innovation are not effectively rectified (i.e., when government environmental subsidies are low), the incentive effect and mechanism of institutional investor involvement on green innovation are more pronounced. Here, this study conducts group regressions based on the mean level of government environmental subsidies. If the incentive effect and mechanism of institutional investors on corporate green innovation are more significant in firms with lower environmental subsidies, this would validate the driving role of environmental externalities.

Similarly, this study further considers the positive externalities of knowledge spillovers. If the incentive effect and mechanism of institutional ownership on corporate green innovation are more pronounced in regions with lower IPP, this would validate the driving role of knowledge spillover externalities. Accordingly, this study identifies whether the “dual externalities” of environment and knowledge spillovers play a key role in the incentive effect of institutional ownership on corporate green innovation.

4.6.1. Results of the Driving Role of “Double Externalities”

To verify the role of “double externalities” of green innovation in the impact of institutional investors on corporate green innovation, this study divides the sample into two groups based on the mean levels of government environmental subsidies and regional IPP and re-conducts group regressions on Equation (1).

Table 11 reports the results of the group regressions based on the mean level of environmental subsidies, which are used to test the driving effect of positive environmental externalities. Columns (1) and (2) of

Table 11 present the regression results for the high environmental subsidy group, while columns (3) and (4) show the results for the low environmental subsidy group. Consistent with our expectations, the impacts of institutional investors on green innovation are substantially positive in setting with low environmental subsidies where environmental externalities are greater. In contrast, there is no effect on firms with high environmental subsidies. Moreover, the coefficient difference tests are significant. This suggests that positive environmental externalities are indeed a significant factor in the impact of institutional ownership on corporate green innovation.

Table 12 presents the results of the group regressions based on the mean level of regional IPP which are used to test the driving effect of positive knowledge spillover externalities. The regression results for the high IPP group are shown in columns (1) and (2), and those for the low IPP group are shown in columns (3) and (4). The results indicate that for firms in regions with low levels of IPP, institutional ownership significantly enhances their green innovation performance. Conversely, for firms in regions with high levels of IPP, there is no correlation between institutional ownership and green innovation. Further, the coefficient difference tests reveal that for green innovation quantity, there is no significant difference in the impact of institutional ownership on green innovation between firms in regions with high and low levels of IPP. However, for green innovation quality, the inter-group difference is significant. Therefore, the positive knowledge spillover externalities are a key factor in the impact of institutional ownership on green innovation, and this impact is more pronounced in terms of green innovation quality.

4.6.2. Mechanism Analysis Under the Driving Role of “Double Externalities”

The empirical results of mechanism analysis based on Equations (2) and (3) are listed in

Table 13. Column (1) shows that InstInvest is positively related to Opacity (coeff. = 0.174;

p-value < 0.01). Column (2) shows a significant positive relationship between institutional ownership and green patent (coeff. = 0.06;

p-value < 0.05). Column (3) shows that institutional ownership is positively and significantly related to green invention (coeff. = 0.073;

p-value < 0.05). These results show that in the presence of corporate information transparency, institutional investors are positively related to green innovation quantity as well as its quality.

To further validate whether the “corporate information transparency” mechanism through which institutional ownership promotes corporate green innovation is driven by the “double externalities”, we conduct subsample mechanism tests. The subsample test results for environmental externalities are shown in

Table 14. Columns (4)–(6) show that for firms with low environmental subsidies, where the positive environmental externalities of green innovation have not been effectively internalized, institutional investors can incentivize green innovation by enhancing corporate transparency. In contrast, in columns (1)–(3) for firms with high environmental subsidies, where the positive environmental externalities have been partially internalized, the effect of institutional investors on green innovation through the corporate transparency mechanism is not significant. In addition, the coefficient difference tests are significant.

Table 15 reports the impact of positive knowledge spillover externalities. Columns (4)–(6) show that for firms in regions with low levels of IPP, where the positive knowledge spillover externalities of green innovation have not been effectively internalized, institutional investors can incentivize green innovation by increasing corporate transparency. Conversely, columns (1)–(3) present that for firms in regions with high levels of IPP, where the gap between private and social returns from green innovation is relatively smaller and firms have a stronger motivation for green innovation, the effect of institutional investors on green innovation through the corporate transparency mechanism is not significant. The coefficient difference tests are also significant.

Therefore, the above results confirm Hypothesis 2 that both positive environmental externalities and positive knowledge spillover externalities are key factors driving institutional investors to promote corporate green innovation through information transparency.

4.7. Heterogeneity Effects

4.7.1. Confucian Culture Heterogeneity Analysis

To test Hypothesis 3, we conduct a heterogeneity analysis based on whether the intensity of Confucian culture is above or below the median of the sample. Drawing on the previous research [

48,

82,

83,

84], we use the number of Confucian academies within a 150-km radius of a firm’s registered address as proxy variable for the intensity of Confucian culture. We first split the sample around the median of Confucian culture intensity and then repeat the baseline regression in Equation (1). The regression results, in

Table 16, show clear evidence that institutional investors positively affect both green patent and green invention at 1% significant level in the group of companies located in weak Confucianism atmosphere, while there are no effects from institutional shareholders to green innovation in the sample of firms in strong Confucian culture. The coefficient difference tests are significant.

4.7.2. Market Sentiment Heterogeneity Analysis

Next, we turn to the heterogeneity in market sentiment in

Table 17. First, we use the total number of posts in the post forum of the listed company as a proxy for market sentiment [

50,

85,

86,

87]. Stock forums operate as unofficial, non-mandatory communication spaces where most participants are small investors who either hold or intend to hold the firm’s stock. The posting volume thus provides a firm-specific, high-frequency indicator of collective sentiment. Then, we divide the sample around the median of the market sentiment. The regression results, in

Table 17, are consistent with our expectation in Hypothesis 4. Columns (1) and (2) show that the positive effects on green innovation are clearly driven by an increase in institutional ownership in the period of high market sentiment. However, there is no significant effect of the institutional investors on green innovation on the chances of low market sentiment, as shown in columns (3) and (4).

4.7.3. Institutional Ownership Heterogeneity Analysis

To further explore the heterogeneity of institutional investors, we distinguish between stable and trading institutional investors, following Sakaki & Jory (2019) and Zhang et al. (2025) [

84,

88]. This distinction captures differences in investment horizons and behavioral characteristics that may shape firms’ green innovation in distinct ways. We analyze the impact of different types of institutional investors on corporate green innovation by dividing firms into two groups, based on institutional ownership volatility.

Following previous research [

84,

88], we classified institutional investors into stable institutional investors and trading institutional investors according to institutional ownership volatility. Specifically, we calculate an indicator to measure institutional ownership volatility.

where

represents institutional ownership for firm i on year t.

represents the standard deviation of institutional ownership over the previous three years, which is used to measure institutional ownership volatility.

represents the median of the volatility of institutional ownership for industry j on year t. Then, we classify institutional investors as stable institutional investors in the firm i on year t if

is greater than or equal to the median. Conversely, we define institutional investors as trading institutional investors in the firm i on year t if

is lower than the median.

We report the results in

Table 18. Column (3) and (4) show that the coefficients of stable institutional ownership are 0.859 and 1.124, which are statistically significant at the 1% level. This indicates a positive correlation between trading institutional ownership and corporate green innovation. Column (1) and (2) show that the coefficients of stable institutional ownership are not significant. This indicates no significant impact of stable institutional ownership on corporate green innovation. This finding provides a novel insight into the heterogeneity of institutional investors. Contrary to the conventional view that long-horizon investors are the primary promoters of sustainability-oriented innovation, the results suggest that short-horizon trading institutional investors are more responsive to market-based ESG incentives and policy signals in China’s transition economy, whereas stable investors tend to adopt a more cautious approach amid institutional uncertainty.

5. Implications and Limitations

5.1. Theoretical Implications

First, this study highlights the positive role of institutional ownership in promoting green innovation, offering new insights from the perspective of externality internalization. Our findings suggest that institutional investors help drive green innovation even in the presence of weak externality internalization, underscoring their compensatory role in China’s transition economy. This extends the classic argument that institutions reduce transaction costs by showing that financial market actors can also mitigate the market failures associated with the double externalities of green innovation [

1,

2,

27]. In doing so, our study emphasizes how external governance actors shape firms’ sustainability strategies under institutional voids [

89], and enrich the growing sustainable finance and ESG stewardship literature [

6,

10,

18], by conceptualizing institutional investors not merely as capital providers but as institutional agents capable of aligning private incentives with social sustainability goals.

Second, this study enriches the literature on corporate governance and sustainable finance by introducing transparency as a key mechanism through which institutional investors exert influence. While prior work has often focused on regulatory disclosure mandates [

90], we show that investors themselves can strategically leverage transparency to alleviate information asymmetries and innovation-related uncertainties. This mechanism not only complements research on corporate information environments [

91], but also extends that private actors increasingly shape environmental outcomes through soft governance and voluntary monitoring [

92]. By framing transparency as an active tool of investor governance, we reposition institutional investors from passive monitors to proactive architects of innovation-oriented disclosure regimes.

Third, our findings contribute to the co-evolutionary perspective on institutions in transitional economies. The Chinese context illustrates how macro-level reforms, such as the split-share reform, interact with micro-level governance mechanisms like institutional investor activism to produce systemic effects on innovation. This shows how ownership structures and capital market reforms shape firm-level innovation trajectories [

93]. By situating institutional investors within the framework of new institutional economics, we demonstrate that they operate at the intersection of formal and informal institutions, bridging regulatory gaps while aligning corporate strategies with long-term environmental objectives. In this way, our study advances theories of institutional change and sustainability governance by showing how financial actors become embedded in the institutional fabric of green transitions [

94].

Beyond the theoretical insights, this study makes a methodological contribution by integrating econometric identification with modern machine learning optimization. Specifically, we employ a double machine learning (DML) framework that combines cross-fitting with flexible estimators such as random forest, gradient boosting, Lasso, and Ridge. This approach ensures that the estimation of nuisance functions satisfies Neyman-orthogonality conditions, thereby delivering unbiased and root-

n consistent estimates even in the presence of high-dimensional confounders [

95]. By capturing both linear and nonlinear dependencies, the framework extends beyond conventional fixed-effects regressions to uncover more complex substitution patterns between institutional investors and formal governance mechanisms. Moreover, the comparative analysis across multiple algorithms highlights the trade-offs between variance reduction in tree-based methods and regularization in penalized linear models, illustrating the complementarity of different optimization strategies. Taken together, our methodological design contributes to the growing literature at the intersection of causal inference and machine learning, providing a replicable framework for studying sustainability transitions and other domains characterized by double externalities and high-dimensional data environments [

74,

77].

5.2. Practical Implications

First, for policymakers in emerging markets, our findings suggest that empowering institutional investors through enhanced disclosure requirements and targeted stewardship incentives can significantly stimulate green innovation, even in contexts where externality pricing mechanisms are not fully developed. Instead of delaying reforms until market-based instruments such as carbon pricing or green subsidies mature, regulators can strategically mobilize institutional investors to bridge the governance gap. Concrete measures may include mandating standardized environmental disclosure, expanding ESG rating systems, and designing tax or reputational incentives that encourage long-term stewardship. These actions can amplify the monitoring capacity of institutional investors and channel private capital toward innovation aligned with national sustainability strategies.

Second, for firms, recognizing the influence of institutional investors in shaping innovation outcomes highlights the need to align internal sustainability agendas with investor expectations. Companies can proactively improve the transparency of their R&D processes, strengthen ESG communication, and integrate environmental objectives into strategic planning to attract and retain long-term oriented investors. By building trust through credible disclosure and consistent performance, firms not only secure financing but also reduce the uncertainty associated with high-risk green innovation projects.

Finally, for institutional investors themselves, the results underscore the value of adopting an active governance approach that goes beyond financial oversight. By systematically integrating environmental considerations into portfolio management, investors can enhance both firm-level innovation and their own long-term returns. This entails refining engagement strategies with portfolio firms, demanding clearer environmental disclosure, and incorporating green innovation metrics into investment decision-making. Such practices enable institutional investors to position themselves as central actors in sustainability transitions, simultaneously achieving fiduciary duties and advancing environmental goals.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

While this study offers novel insights, it has several limitations that suggest directions for future research. First, our market sentiment framework is based on a single-country context. China’s hybrid institutional system, marked by strong government involvement and evolving market institutions, may amplify the compensatory role of institutional investors in internalizing green innovation externalities. Future research could extend this analysis to cross-country settings to assess whether similar mechanisms hold in advanced markets with mature ESG governance systems or in other emerging economies with different institutional voids. Second, although patent data provide an objective and comparable indicator of technological output, they may not capture all forms of green innovation, particularly non-patentable or process-oriented improvements. In addition, macroeconomic fluctuations and regulatory reforms during the study period may have influenced both investor behavior and innovation incentives; however, these contextual dynamics were beyond the analytical focus of this study and were controlled through year and industry fixed effects. Future research could explicitly examine how such macro-level shifts interact with institutional mechanisms to shape green innovation outcomes. Furthermore, while we highlight the importance of financial governance systems in fostering green innovation, further research is needed to explore how specific governance structures may vary across industries or firm sizes. Finally, while this study emphasizes the role of institutional investors, future research could investigate the interactions between different types of investors and their varying impacts on sustainability outcomes.