FusionBullyNet: A Robust English—Arabic Cyberbullying Detection Framework Using Heterogeneous Data and Dual-Encoder Transformer Architecture with Attention Fusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- Integration of heterogeneous bilingual datasets: Multiple heterogeneous English and Arabic cyberbullying datasets were integrated and standardized into a binary classification framework, enabling a robust bilingual analysis while preserving linguistic diversity.

- Development of a unified preprocessing pipeline: A consistent, language-aware preprocessing framework was designed and applied across all datasets to ensure uniformity and improve model reliability.

- Controlled LLM-based Data Augmentation: Large Language Model (LLM)–driven augmentation was employed to improve data diversity, address class imbalance, with filtering strategies applied to preserve semantic consistency and label reliability.

- Bilingual Fusion Architecture (FusionBullyNet): We propose a language-specialized dual encoder transformer architecture that combines independently fine-tuned English and Arabic encoders using an attention-based fusion mechanism, allowing adaptive weighting of bilingual representation. Unlike multilingual transformers that rely on a shared embedding space, the proposed model explicitly preserves language-specific abusive patterns that are critical for cyberbullying detection.

- Extensive Evaluation against Multilingual and Classical Baselines: Comprehensive benchmarking against state-of-the-art multilingual transformer models and machine learning models demonstrated that the proposed bilingual fusion approach consistently outperforms.

3. Research Methodology

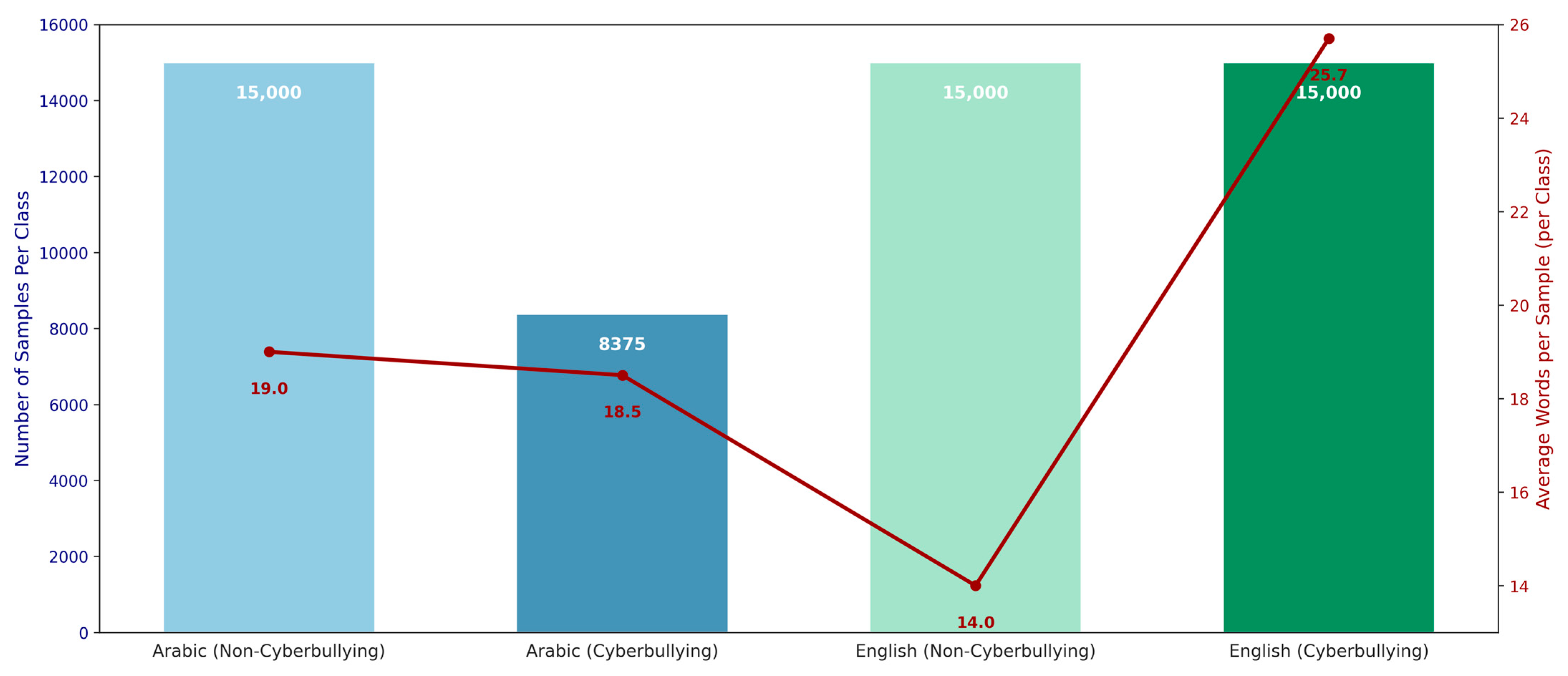

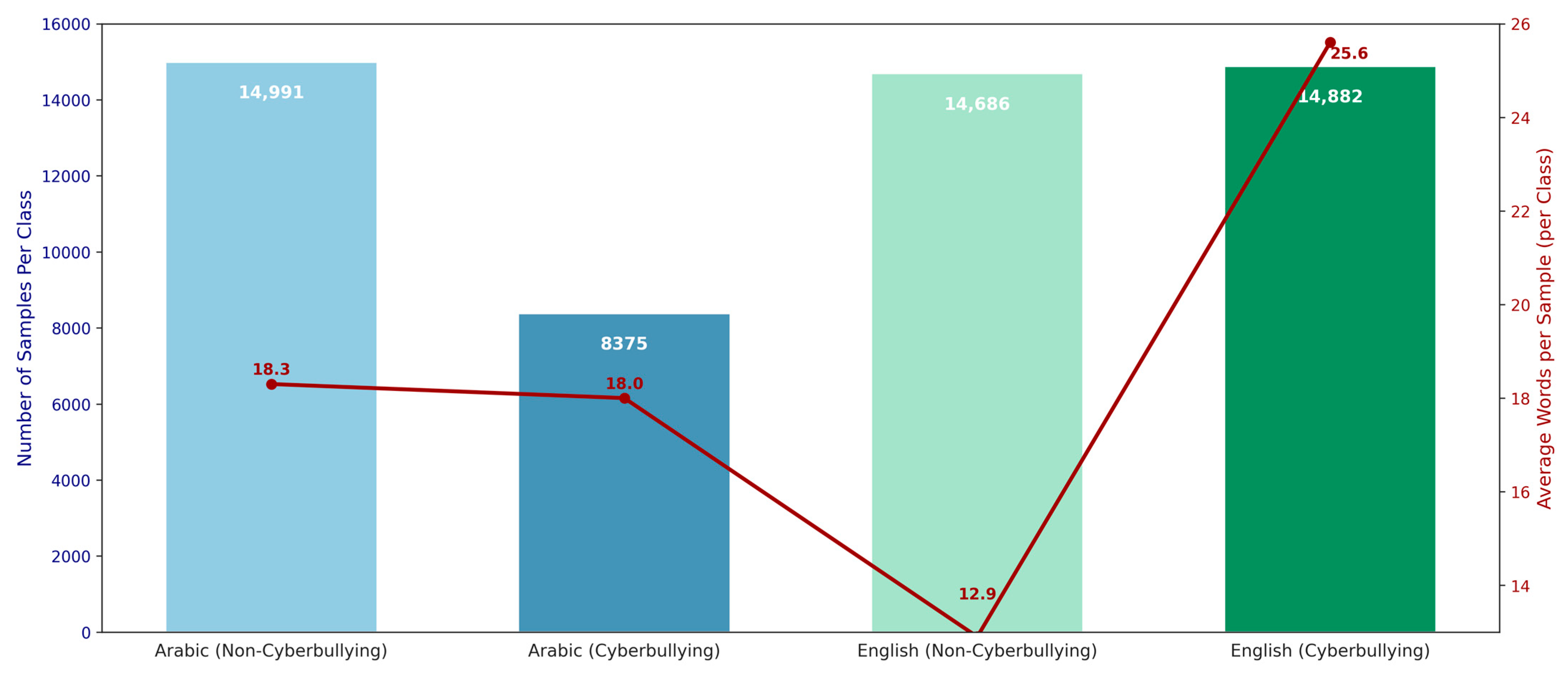

3.1. Dataset Description

3.2. Dataset Pre-Processing

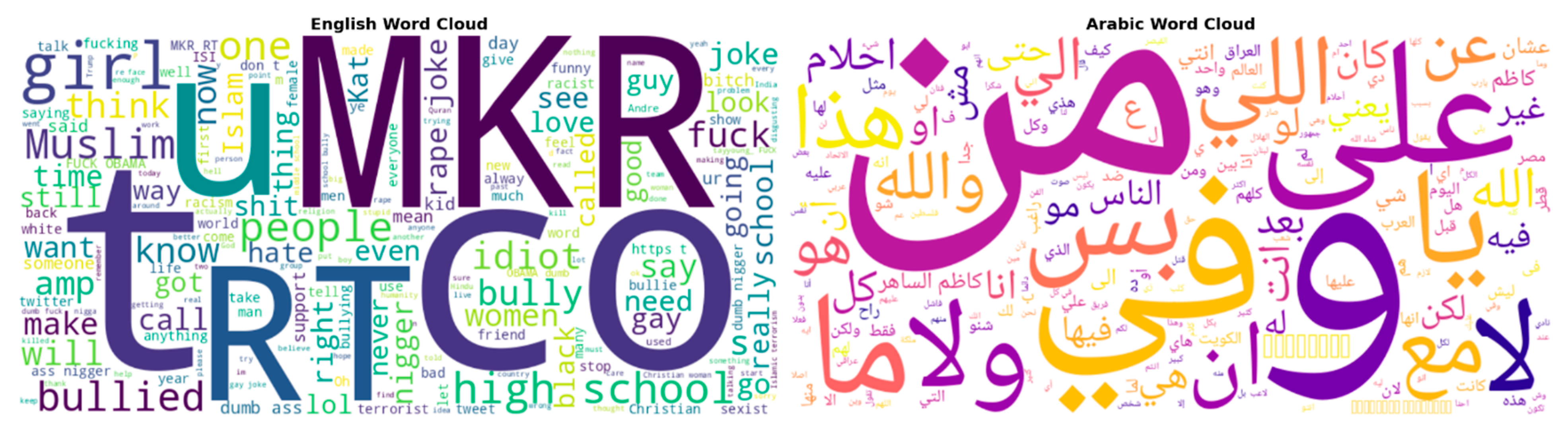

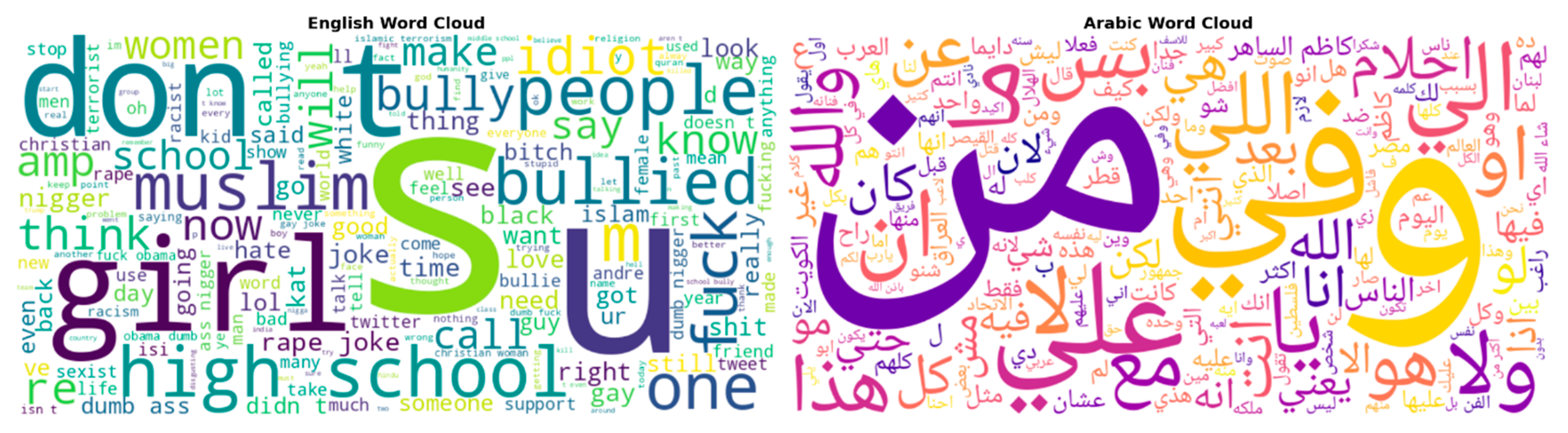

3.3. Exploratory Data Visualization

3.4. Data Augmentation Using Multilingual Large Language Model

3.5. Dataset Language-Based Split Ratio Before and After Augmentation

3.6. Proposed FusionBullyNet (Bilingual Dual-Encoder Model with Attention-Based Fusion)

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Performance Evaluation Metrics

4.2. Experimental Setup

4.3. Model Training Configurations and Results

4.4. Comparison with Multilingual Models

4.5. Comparison with Machine Learning Models

4.6. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Studies

4.7. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mahdi, M.A.; Fati, S.M.; Ragab, M.G.; Hazber, M.A.G.; Ahamad, S.; Saad, S.A.; Al-Shalabi, M. A Novel Hybrid Attention-Based RoBERTa-BiLSTM Model for Cyberbullying Detection. Math. Comput. Appl. 2025, 30, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, P.; Martin-Moratinos, M.; Bella-Fernández, M.; Blasco-Fontecilla, H. Traditional bullying and cyberbullying in the digital age and its associated mental health problems in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 2895–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- One in Six School-Aged Children Experiences Cyberbullying, Finds New WHO/Europe Study. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/27-03-2024-one-in-six-school-aged-children-experiences-cyberbullying--finds-new-who-europe-study?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Kokkinos, C.M.; Baltzidis, E.; Xynogala, D. Prevalence and personality correlates of Facebook bullying among university undergraduates. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 840–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.C.K.; Lin, E.S.S.; Lee, V.K.Y. Does Instagram make you speak ill of others or improve yourself? A daily diary study on the moderating role of malicious and benign envy. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 148, 107873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadysinghe, A.N.; Perera, I.; Wickramasinghe, C.; Darshika, S.; Ekanayake, K.B.; Thilakarathne, I.; Jayasooriya, D.; Wijesiriwardena, Y. Cyber-bullying among Sri Lankan children: Socio-demographic profile, psychosocial behavior pattern and impact of COVID-19 pandemic. In Review, preprint 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Limber, S.P. Psychological, Physical, and Academic Correlates of Cyberbullying and Traditional Bullying. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, S13–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J.W. Bullying, Cyberbullying, and Suicide. Arch. Suicide Res. 2010, 14, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishna, F.; Saini, M.; Solomon, S. Ongoing and online: Children and youth’s perceptions of cyber bullying. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2009, 31, 1222–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forssell, R. Exploring cyberbullying and face-to-face bullying in working life–Prevalence, targets and expressions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messias, E.; Kindrick, K.; Castro, J. School bullying, cyberbullying, or both: Correlates of teen suicidality in the 2011 CDC youth risk behavior survey. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 1063–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patchin, J.W.; Hinduja, S. TWEEN CYBERBULLYING IN 2020; Cyberbullying Research Center: Jupiter, FL, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.developmentaid.org/api/frontend/cms/file/2022/03/CN_Stop_Bullying_Cyber_Bullying_Report_9.30.20.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Cuzzocrea, A.; Akter, M.S.; Shahriar, H.; Bringas, P.G. Cyberbullying Detection, Prevention, and Analysis on Social Media via Trustable LSTM-Autoencoder Networks over Synthetic Data: The TLA-NET Approach. Future Internet 2025, 17, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneer, A.; Fati, S.M. A Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Techniques for Cyberbullying Detection on Twitter. Future Internet 2020, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, Y.; Maulidevi, N.U.; Surendro, K. The Optimization of n-Gram Feature Extraction Based on Term Occurrence for Cyberbullying Classification. Data Sci. J. 2024, 23, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, Y.; Gunawan, D.; Efendi, R. Feature Extraction TF-IDF to Perform Cyberbullying Text Classification: A Literature Review and Future Research Direction. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Information Technology Systems and Innovation, ICITSI 2022, Bandung, Indonesia, 8–9 November 2022; pp. 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoum, J.O. Cyberbullying Detection Neural Networks using Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence, CSCI, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 15–17 December 2021; pp. 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinakar, N.; Reichart, R.; Lieberman, H. Modeling the Detection of Textual Cyberbullying. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 2011, 5, 11–17. Available online: https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/icwsm/article/view/14209 (accessed on 12 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Salawu, S.; He, Y.; Lumsden, J. Approaches to Automated Detection of Cyberbullying: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2020, 11, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. 2017, p. 1. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1706.03762 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Saha, S. CyberBERT: BERT for cyberbullying identification. Multimed. Syst. 2020, 28, 1897–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conneau, A.; Khandelwal, K.; Goyal, N.; Chaudhary, V.; Wenzek, G.; Guzmán, F.; Grave, E.; Ott, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Unsupervised Cross-lingual Representation Learning at Scale. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 8440–8451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipo, A.G.; Sarwatt, D.S.; Ding, J.; Daneshmand, M.; Ning, H. Assessing Text Classification Methods for Cyberbullying Detection on Social Media Platform. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 20, 7602–7616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzeh, M.; Alhijawi, B.; Tabbaza, A.; Alabboshi, O.; Hamdan, N.; Jaser, D. Arabic cyberbullying detection system using convolutional neural network and multi-head attention. Int. J. Speech Technol. 2024, 27, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, M.A.; Fati, S.M.; Hazber, M.A.G.; Ahamad, S.; Saad, S.A. Enhancing Arabic Cyberbullying Detection with End-to-End Transformer Model. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2024, 141, 1651–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljalaoud, H.; Dashtipour, K.; Al-Dubai, A.Y. Arabic Cyberbullying Detection: A Comprehensive Review of Datasets and Methodologies. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 69021–69038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhao, B.; Huang, C. Cyberbullying Detection in Social Networks Using Bi-GRU with Self-Attention Mechanism. Information 2021, 12, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, Z.; Hovy, D. Hateful Symbols or Hateful People? Predictive Features for Hate Speech Detection on Twitter. In Proceedings of the NAACL-HLT 2016, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–17 June 2016; pp. 88–93. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/N16-2013.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Davidson, T.; Warmsley, D.; Macy, M.; Weber, I. Automated Hate Speech Detection and the Problem of Offensive Language. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 2017, 11, 512–551. Available online: https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/14955 (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wulczyn, E.; Thain, N.; Dixon, L. Ex machina: Personal attacks seen at scale. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, S.; Yadav, A.K.; Kumar, M.; Yadav, D. Cyberbullying detection from tweets using deep learning. Kybernetes 2022, 51, 2695–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewani, A.; Memon, M.A.; Bhatti, S. Cyberbullying detection: Advanced preprocessing techniques & deep learning architecture for Roman Urdu data. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gada, M.; Damania, K.; Sankhe, S. Cyberbullying Detection using LSTM-CNN architecture and its applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics, ICCCI, Coimbatore, India, 27–29 January 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.F.; Mahmud, Z.; Biash, Z.T.; Ryen, A.A.N.; Hossain, A.; Ashraf, F.B. Cyberbullying Detection Using Deep Neural Network from Social Media Comments in Bangla Language. 2021. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2106.04506 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Yi, P.; Zubiaga, A. Cyberbullying detection across social media platforms via platform-aware adversarial encoding. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 2022, 16, 1430–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.; Gupta, A. Performance Comparison of Simple Transformer and Res-CNN-BiLSTM for Cyberbullying Classification. 2022. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2206.02206 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Tashtoush, Y.; Banysalim, A.; Maabreh, M.; Al-Eidi, S.; Karajeh, O.; Zahariev, P. A Deep Learning Framework for Arabic Cyberbullying Detection in Social Networks. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 83, 3113–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fati, S.M.; Muneer, A.; Alwadain, A.; Balogun, A.O. Cyberbullying Detection on Twitter Using Deep Learning-Based Attention Mechanisms and Continuous Bag of Words Feature Extraction. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, M.S.; Shahriar, H.; Cuzzocrea, A. A Trustable LSTM-Autoencoder Network for Cyberbullying Detection on Social Media Using Synthetic Data. 2023. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2308.09722 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Wahid, Z.; Al Imran, A. Multi-feature Transformer for Multiclass Cyberbullying Detection in Bangla. IFIP Adv. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2023, 675, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihab-Us-Sakib, S.; Rahman, M.R.; Forhad, M.S.A.; Aziz, M.A. Cyberbullying detection of resource constrained language from social media using transformer-based approach. Nat. Lang. Process. J. 2024, 9, 100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Huang, K.; Perez, A.; Yang, G.; Li, J.J.; Morreale, P.; Kruger, D.; Jiang, R. Bias and Cyberbullying Detection and Data Generation Using Transformer Artificial Intelligence Models and Top Large Language Models. Electronics 2024, 13, 3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddoura, S.; Nassar, R. Language Model-Based Approach for Multiclass Cyberbullying Detection. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Singapore, 2025; Volume 15437, pp. 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Batista, K.; Gómez-Sánchez, J.; Fernandez-Basso, C. Improving automatic cyberbullying detection in social network environments by fine-tuning a pre-trained sentence transformer language model. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2024, 14, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, J. Understanding and Fighting Bullying with Machine Learning-UWDC-UW-Madison Libraries. Available online: https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/ARXXPUFZWBRX4R9C (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Bayzick, J.; Kontostathis, A.; Edwards, L. Detecting the presence of cyberbullying using computer software. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Web Science Con-ference WebSci’11, Koblenz, Germany, 15–17 June 2011; pp. 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, S.S.; Karim, R.; Miraz, M.H. Deep Learning Based Cyberbullying Detection in Bangla Language. Ann. Emerg. Technol. Comput. 2024, 8, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J.L. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1412.6980. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1412.6980 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Kumar, D. A Hybrid DeBERTa and Gated Broad Learning System for Cyberbullying Detection in English Text. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2506.16052 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Mathew, B.; Saha, P.; Yimam, S.M.; Biemann, C.; Goyal, P.; Mukherjee, A. HateXplain: A Benchmark Dataset for Explainable Hate Speech Detection. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 14867–14875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fu, K.; Lu, C.T. SOSNet: A Graph Convolutional Network Approach to Fine-Grained Cyberbullying Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–13 December 2020; pp. 1699–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, N.; Choudhury, S.; Razi, F. A Comprehensive Dataset for Automated Cyberbullying Detection. Mendeley Data 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D. Cyberbullying Detection in Hinglish Text Using MURIL and Explainable AI. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2506.16066 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Bohra, A.; Vijay, D.; Singh, V.; Akhtar, S.S.; Shrivastava, M. A Dataset of Hindi-English Code-Mixed Social Media Text for Hate Speech Detection. 2018, pp. 36–41. Available online: https://github.com/deepanshu1995/HateSpeech-Hindi-English-Code-Mixed-Social-Media-Text (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Maity, K.; Jain, R.; Jha, P.; Saha, S. Explainable Cyberbullying Detection in Hinglish: A Generative Approach. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2024, 11, 3338–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, K.; Saha, S.; Bhattacharyya, P. Emoji, Sentiment and Emotion Aided Cyberbullying Detection in Hinglish. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2023, 10, 2411–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandl, T.; Modha, S.; Shahi, G.K.; Madhu, H.; Satapara, S.; Majumder, P.; Schäfer, J.; Ranasinghe, T.; Zampieri, M.; Nandini, D.; et al. Overview of the HASOC Subtrack at FIRE 2021: Hate Speech and Offensive Content Identification in English and Indo-Aryan Languages. 2021. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2112.09301 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Kaware, P. Indo-HateSpeech. Mendeley Data 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, A.K. Benchmarking Aggression Identification in Social Media. 2018. Available online: https://research.universityofgalway.ie/en/publications/benchmarking-aggression-identification-in-social-media (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Prama, T.T.; Amrin, J.F.; Anwar, M.M.; Sarker, I.H. AI Enabled User-Specific Cyberbullying Severity Detection with Explainability. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2503.10650 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Purkayastha, B.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Talukdar, M.T.I.; Shahpasand, M. Advancing Cyberbullying Detection: A Hybrid Machine Learning and Deep Learning Framework for Social Media Analysis. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, Porto, Portugal, 4–6 April 2025; Volume 2, pp. 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, A.M.; Guirguis, S.K.; Madbouly, M.M. An optimized Arabic cyberbullying detection approach based on genetic algorithms. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 38479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyberbullying Classification. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/andrewmvd/cyberbullying-classification (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Cyberbullying Dataset. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/saurabhshahane/cyberbullying-dataset (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- ArbCyD: Arabic Cyberbullying Dataset. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/monarasheedalroqi/arbcyd-arabic-cyberbullying-dataset (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Shannag, F. ArCyC: A Fully Annotated Arabic Cyberbullying Corpus. Mendeley Data 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GitHub-Omammar167/Arabic-Abusive-Datasets: Available Arabic abusive and cyber bullying Datasets. Available online: https://github.com/omammar167/Arabic-Abusive-Datasets (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Hegazi, M.O.; Al-Dossari, Y.; Al-Yahy, A.; Al-Sumari, A.; Hilal, A. Preprocessing Arabic text on social media. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, J.; Hamerlik, E.; Schwartz, R.; Smith, N.A.; Kornai, A. Morphosyntactic Probing of Multilingual BERT Models. Nat. Lang. Eng. 2023, 30, 753–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaoud, M.; Syed, M. On the Importance of Tokenization in Arabic Embedding Models. 2020, pp. 119–129. Available online: https://github.com/attardi/wikiextractor (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Miyajiwala, A.; Ladkat, A.; Jagadale, S.; Joshi, R. On Sensitivity of Deep Learning Based Text Classification Algorithms to Practical Input Perturbations. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.00318 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Turki, T.; Roy, S.S. Novel Hate Speech Detection Using Word Cloud Visualization and Ensemble Learning Coupled with Count Vectorizer. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muennighoff, N.; Wang, T.; Sutawika, L.; Roberts, A.; Biderman, S.; Le Scao, T.; Bari, M.S.; Shen, S.; Yong, Z.X.; Schoelkopf, H.; et al. Crosslingual Generalization through Multitask Finetuning. Proc. Annu. Meet. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2023, 1, 15991–16111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigscience/mt0-Base Hugging Face. Available online: https://huggingface.co/bigscience/mt0-base (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach. 2019. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1907.11692 (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- FacebookAI/Roberta-Base Hugging Face. Available online: https://huggingface.co/FacebookAI/roberta-base (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Antoun, W.; Baly, F.; Hajj, H. AraBERT: Transformer-Based Model for Arabic Language Understanding. 2020. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2003.00104 (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Kaggle: Your Home for Data Science. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/ (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Welcome to Python.org. Available online: https://www.python.org/ (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. Adv. Neural Inf. Process Syst. 2019, 32. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1912.01703 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Wolf, T.; Debut, L.; Sanh, V.; Chaumond, J.; Delangue, C.; Moi, A.; Cistac, P.; Rault, T.; R´emi, L.; Funtowicz, M.; et al. HuggingFace’s Transformers: State-of-the-Art Natural Language Processing. 2019. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1910.03771 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- FacebookAI/Xlm-Roberta-Base Hugging Face. Available online: https://huggingface.co/FacebookAI/xlm-roberta-base (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- He, P.; Gao, J.; Chen, W. DeBERTaV3: Improving DeBERTa using ELECTRA-Style Pre-Training with Gradient-Disentangled Embedding Sharing. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2111.09543 (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Microsoft/mDeberta-v3-Base Hugging Face. Available online: https://huggingface.co/microsoft/mdeberta-v3-base (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Google-Bert/Bert-Base-Multilingual-Cased Hugging Face. Available online: https://huggingface.co/google-bert/bert-base-multilingual-cased (accessed on 14 December 2025).

| Study | Language/Dataset | Architecture | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fang et al. (2021) [28] | English (Social media posts) | Bi-GRU with self-attention | Weighted average precisions of 0.849, 0.961, and 0.943 across all three datasets ([29,30,31]). |

| Bharti et al. (2021) [32] | English (Tweets) | GloVe embeddings + Bi-LSTM | Accuracy 92.60% |

| Dewani et al. (2021) [33] | Roman Urdu (Custom Dataset) | Hybrid RNN (LSTM/Bi-LSTM) + CNN with preprocessing | Accuracy of 85.5% |

| Gada et al. (2021) [34] | English | LSTM + CNN hybrid | Accuracy of 95.2% |

| Ahmed et al. (2021) [35] | Bengali | Deep neural + ensemble for multiclass | Accuracy of 85% for multiclass |

| Yi et al. (2022) [36] | English/3 Platforms | Adversarial Encoding + Transformers | Average macro F1 0.693 (69.30%) |

| Joshi et al. (2022) [37] | English | Simple Transformer vs. hybrid Res-CNN-BiLSTM | Training and validation accuracy are much better in the simple transformer case |

| Tashtoush et al. (2022) [38] | Arabic YouTube Comments | CNN, LSTM, Bi-LSTM, CNN-LSTM Hybrid | Binary classification: CNN & CNN-LSTM ≈ 91.9% accuracy Multiclass: LSTM & Bi-LSTM ≈ 89.5% accuracy |

| Fati et al. (2023) [39] | English (Twitter) | Attention + Continuous bag of words | Accuracy 94.49% |

| Akter et al. (2023) [40] | English, Bangla, Hindi | LSTM-Autoencoder + Synthetic data | ≈95% across datasets |

| Wahid et al. (2023) [41] | Bangla | Transformer + lexical + contextual + semantic features | 98% for threats and 90% for sarcastic |

| Sihab-Us-Sakib et al. (2024) [42] | Bengali | Fine-Tuned Transformer | Accuracy 82.61% |

| Kumar et al. (2024) [43] | English (Twitter + Synthetic Data) | Multiple Transformers | Effective detection of bias and cyberbullying |

| Kaddoura et al. (2024) [44] | English | BERT vs. LLM | Accuracy 83.67% |

| Gutiérrez-Batista et al. (2024) [45] | English (BullyingV3.0 [46], MySpace [47], Hate-Speech [29]) | Pre-trained Sentence Transformer fine-tuned | ~83% and ~97% across datasets |

| Nath et al. (2024) [48] | Bengali | Two Layer Bi-LSTM | 95.08% Accuracy |

| Kumar (2025) [50] | English (HateXplain [51], SOSNet [52], Mendeley (Mendeley-I, and Mendeley-II) [53]) | Hybrid DeBERTa + GBLS | 79.3–95.41% accuracy |

| Kumar (2025) [54] | Hinglish (Bohra [55], BullyExplain [56], BullySentemo [57], HASOC-2021 [58], Mendeley [59] and Kumar dataset [60]) | MURIL Transformer | 83.92–94.63% accuracy |

| Prama et al. (2025) [61] | English | LSTM + User Specific Data | 98% Accuracy |

| Purkayastha et al. (2025) [62] | Twitter Dataset Binary | ML (RF, XGB) vs. DL (Bi-LSTM, BiGRU, BERT) | 92% Accuracy |

| Eisa et al. (2025) [63] | Arabic | SVM + GA-FS (Genetic Algorithm (GA)-based feature selection) | Accuracy after GA-FS: 71.76 |

| Text | Language | Cyberbullying |

|---|---|---|

| “مابظن في أحلى وأعذب من صوتك” | Arabic | No |

| “رضا عبعال من ازبل الشخصيات اللي ممكن تسمعها او تضيع وقتك علشان تسمعه حتي لو حيضحكك شخصيه بنت ١٠٠تين كلب واللي بيطلعوه ع الشاشات اوسخ منه الواحد قرف من الاشكال المعفنه دي اللي الكوره عملت منهم بني ادمين ودوقتهم الفلوس وهما في الاصل كانوا حثاله متلقحه في كوم زباله” | Arabic | Yes |

| “Just discovered what happens when jeans are too big while wearing over a swim. Whelp. Time to make a belt.” | English | No |

| “Only person that’s still being a dumb dickwad is D’Undre. But fuck him. Big lip, buttfucking nigger.” | English | Yes |

| Parameter | Description/Value |

|---|---|

| Language Model | bigscience/mt0-base |

| Augmentation Type | Multilingual Paraphrasing |

| Input Languages | English, Arabic |

| Generation Mode | Batch-Wise (32 Batch Size) |

| Maximum Input Length | 128 Tokens |

| Maximum Output Length | 128 Tokens |

| Decoding Strategy | Beam search (num_beams = 4), top-p sampling (top_p = 0.95), temperature = 0.9 |

| Impact | Increased train samples and balanced class distribution across all languages |

| Split | Language | Non-Cyberbullying | Cyberbullying | Total Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train (Before) | Arabic | 11,993 | 6700 | 18,693 |

| English | 11,749 | 11,905 | 23,654 | |

| Train (After) | Arabic | 11,993 | 11,993 | 23,986 |

| English | 11,993 | 11,993 | 23,986 | |

| Validation | Arabic | 1499 | 838 | 2337 |

| English | 1468 | 1488 | 2956 | |

| Test | Arabic | 1499 | 837 | 2336 |

| English | 1469 | 1489 | 2958 |

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Encoders | RoBERTa-Base (12 layers)/aubmindlab/bert-base-arabertv02-twitter (12 layers) |

| Projection | Liner Transformation to Shared latent dimension (1024) |

| Fusion | Multi-Head Attention (4 heads) |

| Classifier | Dropout (0.4), Dense (ReLU) |

| Parallelization | Dual-GPU setup using the Accelerate framework |

| Precision | Automatic Mixed Precision (AMP) |

| Loss Function | Weighted Cross Entropy + Label Smoothing (0.1) |

| Optimizer | AdamW with weight decay of 0.01 |

| Technique | Purpose | Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Layer-wise LR Decay (LLRD) | Preserves low-level linguistic features while adapting deeper layers | Decay = 0.9 |

| Label Smoothing | Improves model calibration and mitigates overfitting | ε = 0.1 |

| Gradient Accumulation | Simulates a larger effective batch size with limited GPU memory | 2 steps → effective batch 128 |

| Automatic Mixed Precision (AMP) | Reduces memory use and increases throughput | Enabled (autocast, GradScaler) |

| Early Stopping | Prevents over-training when validation loss plateaus | Patience = 5 |

| Gradient Clipping | Stabilizes training by preventing exploding gradients | Max norm = 0.8 |

| Encoder | Total Layers | Initially Frozen | Initially Trainable | Layers Unfrozen per Step | Patience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English (RoBERTa-Base) | 12 | 10 | 2 | +2 | 2 |

| Arabic (aubmindlab/bert-base-arabertv02-twitter) | 12 | 10 | 2 | +2 | 2 |

| Component | Specifications |

|---|---|

| GPU | 2 × NVIDIA T4 |

| GPU Memory (1st GPU) | 15 GB |

| GPU Memory (2nd GPU) | 15 GB |

| System RAM | 30 GB |

| Disk Storage | 57.6 GB |

| Operating Platform | Kaggle Free Service |

| Programming Language | Python (v3.10) |

| Training Hyperparameters | Value/Setting |

|---|---|

| Optimizer | AdamW |

| Encoder Learning Rate | 7 × 10−6 |

| Classifier Learning Rate | 1 × 10−5 |

| Batch Size | 64 (effective 128 with accumulation) |

| Scheduler | Linear decay with 15% warmup |

| Loss Function | Cross-Entropy with label smoothing (ε = 0.1) |

| Epochs | 30 |

| Early Stopping | Patience = 5 |

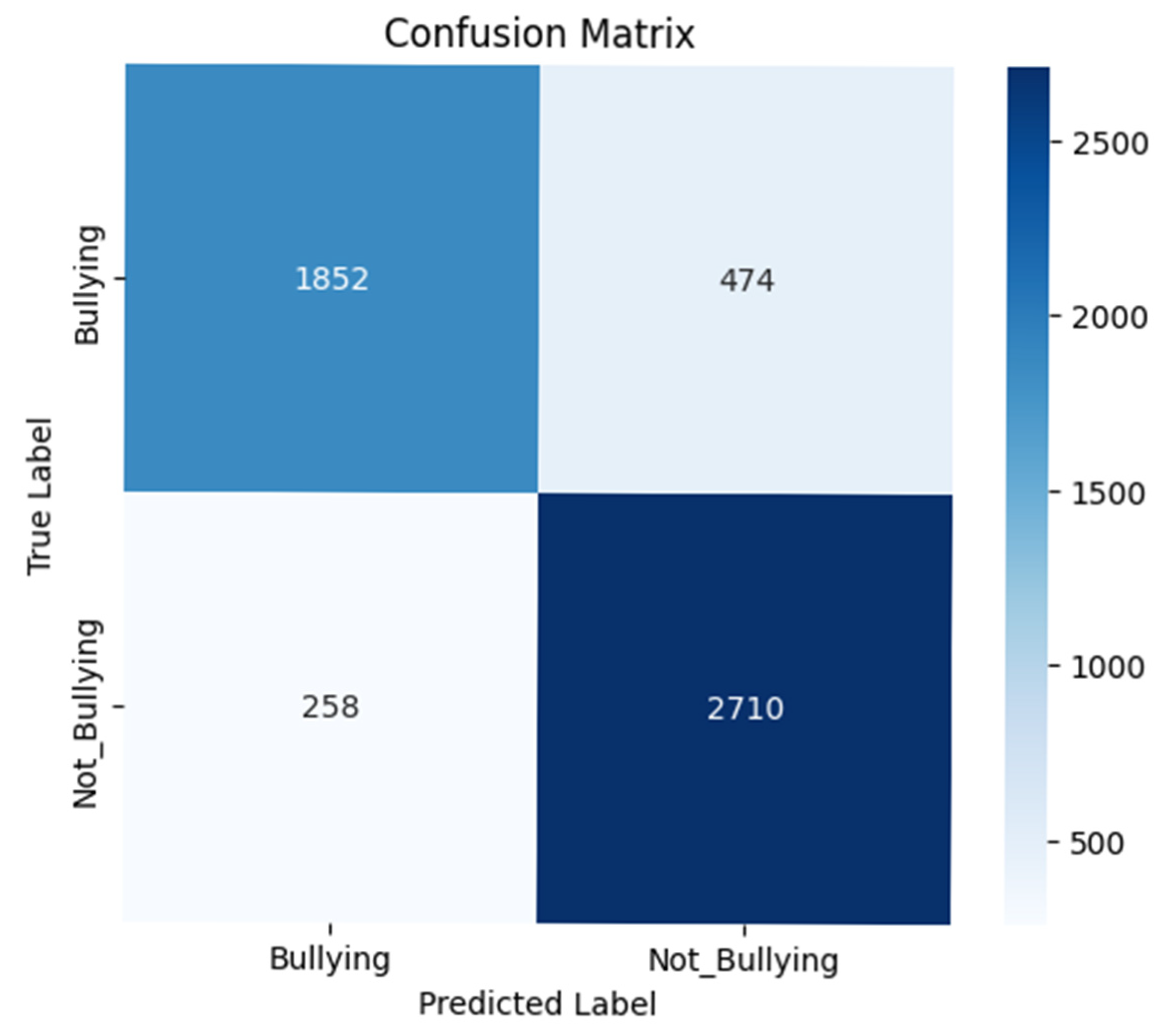

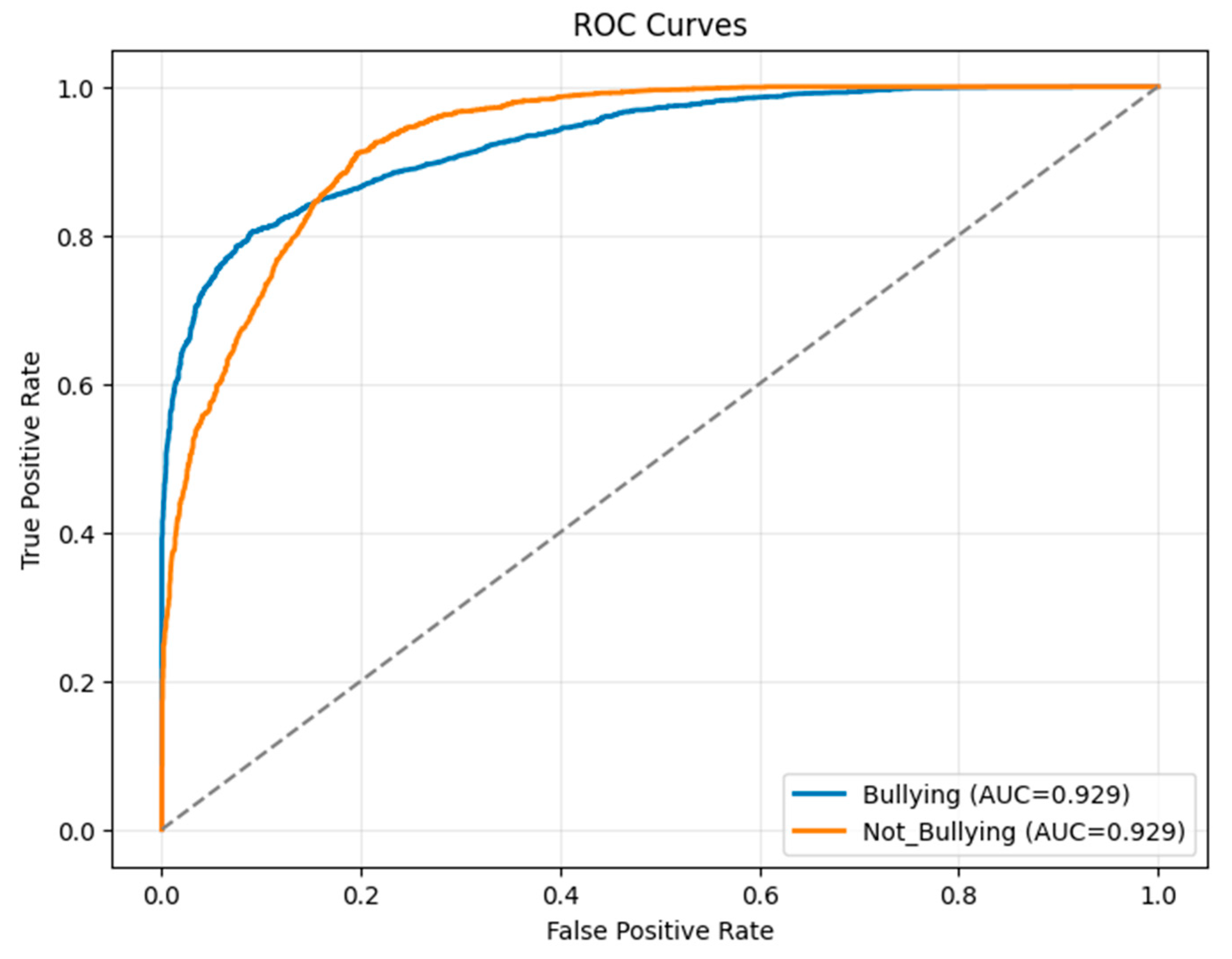

| Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bullying | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 2326 |

| Not_Bullying | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 2968 |

| Macro Avg | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 5294 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 5294 |

| Overall Accuracy = 0.86 | ||||

| Models | Accuracy | Weighted Precision | Weighted Recall | Weighed F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XLM-Roberta-base | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| mdeberta-v3-base | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| google-bert/bert-base-multilingual-cased | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| Proposed FusionBullyNet | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| Models | Accuracy | Weighted Precision | Weighted Recall | Weighed F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LogisticRegression | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.81 |

| LinearSVC | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 |

| MultinomialNB | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| Random Forest Classifier | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.81 |

| Extra Trees Classifier | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 |

| XGBoost Classifier | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.81 |

| LightGBM Classifier | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.81 |

| KNeighbors Classifier | 0.59 | 0.70 | 0.59 | 0.47 |

| SGDClassifier Classifier | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.81 |

| Proposed FusionBullyNet | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| Study | Language | Model | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bharti et al. (2021) [32] | English | GloVe embeddings + Bi-LSTM | Accuracy: 92.60% |

| Kaddoura et al. (2024) [44] | English | BERT vs LLM | Accuracy 83.67% |

| Purkayastha et al. (2025) [62] | English | ML (RF, XGB) vs DL (Bi-LSTM, BiGRU, BERT) | 92% Accuracy |

| Ahmed et al. (2021) [35] | Bengali | Deep neural + ensemble for multiclass | Accuracy: 85% |

| Sihab-Us-Sakib et al. (2024) [42] | Bengali | Fine-Tuned Transformer | Accuracy 82.61% |

| Tashtoush et al. (2022) [38] | Arabic | CNN, LSTM, Bi-LSTM, CNN-LSTM Hybrid | Binary classification: CNN & CNN-LSTM ≈ 91.9% accuracy Multiclass: LSTM & Bi-LSTM ≈ 89.5% accuracy |

| Eisa et al. (2025) [63] | Arabic | SVM + GA-FS (Genetic Algorithm (GA)-based feature selection) | Accuracy after GA-FS: 71.76 |

| Proposed FusionBullyNet | English + Arabic | Transformer Models + Fusion | Accuracy: 0.86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mahdi, M.A.; Arshed, M.A.; Mumtaz, S. FusionBullyNet: A Robust English—Arabic Cyberbullying Detection Framework Using Heterogeneous Data and Dual-Encoder Transformer Architecture with Attention Fusion. Mathematics 2026, 14, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010170

Mahdi MA, Arshed MA, Mumtaz S. FusionBullyNet: A Robust English—Arabic Cyberbullying Detection Framework Using Heterogeneous Data and Dual-Encoder Transformer Architecture with Attention Fusion. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010170

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahdi, Mohammed A., Muhammad Asad Arshed, and Shahzad Mumtaz. 2026. "FusionBullyNet: A Robust English—Arabic Cyberbullying Detection Framework Using Heterogeneous Data and Dual-Encoder Transformer Architecture with Attention Fusion" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010170

APA StyleMahdi, M. A., Arshed, M. A., & Mumtaz, S. (2026). FusionBullyNet: A Robust English—Arabic Cyberbullying Detection Framework Using Heterogeneous Data and Dual-Encoder Transformer Architecture with Attention Fusion. Mathematics, 14(1), 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010170