1. Introduction

The rapid evolution of intelligent transportation systems and the proliferation of connected vehicles have ushered in a new era of V2X communication, fundamentally transforming road safety, traffic efficiency, and mobility services. Modern vehicular networks generate an unprecedented diversity of applications ranging from safety-critical collision avoidance and autonomous driving control to bandwidth-intensive infotainment streaming and massive-scale traffic information collection. Each of these applications imposes distinct and often conflicting QoS requirements, including Ultra-Reliable Low-Latency Communication (URLLC) for safety applications, Enhanced Mobile Broadband (eMBB) for multimedia services, and Massive Machine-Type Communication (mMTC) for sensor data aggregation. Accommodating such heterogeneous service demands within a unified communication infrastructure poses formidable challenges for resource management in next-generation vehicular networks. This complexity necessitates granular QoS provisioning across the protocol stack, particularly at the Physical and MAC layers, to facilitate rigorous service isolation [

1,

2,

3]. The fundamental significance of such hierarchical differentiation lies in its capacity to decouple the inherently contradictory performance objectives of heterogeneous V2X services. In a shared wireless environment, a “one-size-fits-all” approach is insufficient; without targeted differentiation, high-throughput eMBB traffic would inevitably compromise the deterministic low-latency essential for URLLC safety alerts. Consequently, layered QoS mechanisms are not merely an optimization but a safety-critical prerequisite, ensuring that life-saving signaling remains shielded from resource contention while maintaining overall network efficiency.

The emergence of 5G network slicing technology provides a promising architectural paradigm to address this heterogeneity challenge [

4,

5]. Network slicing enables the creation of multiple virtual networks on shared physical infrastructure, with each slice customized to support specific service characteristics and QoS requirements [

6,

7]. As illustrated in

Figure 1, a network slicing architecture can logically partition resources into three specialized slices: the eMBB slice supporting high-bandwidth services such as in-car video streaming, the mMTC slice handling massive low-rate connections for vehicle sensor data uploading, and the URLLC slice ensuring ultra-low latency and high reliability for autonomous driving control. Each slice operates on the same physical infrastructure layer while maintaining service isolation and providing differentiated QoS guarantees. By orchestrating these dedicated slices through a centralized traffic platform, operators can provide service guarantees tailored to diverse vehicular applications, enabling vehicles with heterogeneous service requirements to access appropriate network resources dynamically.

However, realizing effective network slicing in vehicular environments introduces three critical challenges that existing approaches [

3,

7] have yet to fully address. First, the interdependency between slice selection and resource allocation remains underexplored. Traditional approaches typically pre-assign services to slices based solely on service categories (e.g., all safety messages to the URLLC slice, all entertainment traffic to the eMBB slice), then perform resource allocation within each slice independently. This separation fails to account for dynamic load imbalances across slices and overlooks opportunities for services with mixed QoS requirements to flexibly access multiple slice types. When traffic patterns fluctuate or certain slices become congested, static assignment strategies cannot redistribute load effectively, leading to resource fragmentation where some slices remain underutilized while others face capacity shortages. Second, the integration of heterogeneous 5G and RSU infrastructure requires coordinated orchestration strategies. In typical urban vehicular networks, communication infrastructure comprises both 5G base stations providing wide-area coverage with higher mobility support and RSUs deployed at intersections offering high-capacity, low-latency communication within limited coverage zones. While existing research has explored resource allocation in either 5G networks or RSU-assisted systems separately, efficient joint orchestration of these heterogeneous resources across multiple network slices, exploiting their complementary coverage and capacity characteristics, remains an open challenge. The dynamic and mobile nature of vehicular scenarios further complicates this orchestration: vehicles move rapidly across coverage areas, service demands fluctuate unpredictably with traffic patterns, and radio propagation characteristics vary significantly between deployment scenarios. Third, meeting stringent real-time constraints demands algorithms with deterministic execution guarantees. The 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) specifications mandate 20 ms end-to-end latency for safety-critical V2X services [

8], imposing strict requirements on resource allocation decision cycles. While reinforcement learning (RL) methods have demonstrated impressive adaptability to dynamic vehicular environments, their training convergence times and decision latencies remain unpredictable, potentially violating real-time requirements during critical safety scenarios. Population-based metaheuristic algorithms similarly lack deterministic runtime bounds, with execution times varying significantly across problem instances. Safety-critical vehicular applications require resource allocation algorithms that guarantee solution delivery within predictable time windows, ensuring consistent performance regardless of network complexity or operational conditions.

Addressing these three challenges, this paper proposes a novel resource allocation framework that jointly optimizes slice selection and resource allocation to maximize weighted system transmission rate in sliced vehicular networks. The framework enables direct user-to-slice access where services are not pre-assigned to slices but instead dynamically matched to appropriate slices during the allocation process based on real-time QoS requirements and current resource availability across all slices. The core contribution lies in a constructive heuristic algorithm that: (1) jointly determines service-to-slice assignments and resource distributions through utility-driven prioritization, (2) coordinates 5G and RSU resource blocks via a hierarchical allocation strategy that prioritizes 5G resources before activating RSU capacity to exploit their complementary characteristics, and (3) guarantees solution delivery within strict real-time bounds (20 ms decision cycles). A two-phase allocation mechanism further enhances performance, where the first phase performs priority-based allocation for initially assigned services, while the second phase implements backfilling to serve previously rejected requests using residual capacity, thereby improving overall system throughput and resource utilization.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on network slicing and resource allocation for vehicular communications.

Section 3 formulates the mathematical optimization model, defining the problem, constraints and objective function.

Section 4 presents the constructive heuristic algorithm with a detailed pseudocode.

Section 5 presents comprehensive experimental results evaluating algorithm performance under various scenarios and parameter settings. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper with a summary of contributions and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

Resource allocation in 5G network slicing for vehicular communications has attracted considerable attention, as modern vehicular networks must efficiently distribute limited resources among heterogeneous users with diverse QoS requirements. The emergence of V2X communication introduces unprecedented service heterogeneity, ranging from safety-critical URLLC for collision avoidance and emergency braking to bandwidth-intensive eMBB for in-vehicle infotainment and High-Definition (HD) map updates, along with mMTC for dense sensor data aggregation and traffic monitoring [

4,

5]. Network slicing has emerged as a key enabling technology that creates logically isolated virtual networks over shared physical infrastructure, with each slice tailored to specific service characteristics [

6]. Research efforts addressing resource allocation in sliced vehicular networks fall broadly into three categories: optimization-based methods that provide formal performance guarantees, learning-based frameworks that adapt to dynamic environments, and hybrid strategies that combine both paradigms.

Optimization-based approaches formulate resource allocation as mathematical programming problems to achieve optimal or near-optimal solutions under specified constraints. Su et al. [

7] surveyed resource allocation in 5G network slicing, classifying optimization models into general, economic/game-theoretic, and prediction-based categories to address objectives such as throughput, latency, and fairness. Building on these principles, Chen et al. [

3] proposed a service-oriented dynamic resource slicing framework for vehicular networks, integrating joint resource block allocation and power control through Lyapunov optimization. Their JRPSV algorithm adaptively adjusts slice resources between eMBB and URLLC services to maximize long-term system capacity while ensuring queue stability. Lee et al. [

9] proposed a dynamic network slicing framework for multitenant heterogeneous cloud radio access networks (H-CRANs) that uses convex optimization to maximize resource utilization while ensuring tenant-specific QoS. The two-level scheme optimizes admission control, user association, and resource allocation, achieving higher throughput, fairness, and QoS than baseline methods. Game-theoretic formulations have also been explored: Cui et al. [

10] applied a Stackelberg game model where roadside units act as leaders allocating resources to URLLC and eMBB slices as followers, minimizing Age-of-Information and delay for URLLC traffic while ensuring eMBB throughput requirements, achieving 30% improvement in URLLC freshness and delay performance compared to rigid slicing allocations.

The complexity and rapid variability of vehicular networks have motivated artificial intelligence-driven resource management approaches for adaptive network slicing. RL enables systems to learn slicing policies from experience without explicit global optimization models, discovering resource sharing strategies that outperform fixed or greedy allocations as network conditions evolve. Albonda and Pérez-Romero [

2] proposed an RL-based radio access network (RAN) slicing strategy for heterogeneous networks supporting eMBB and V2X services, combining offline Q-learning to discover effective slicing policies with lightweight runtime heuristics for allocation decisions, thereby achieving more efficient spectrum utilization between broadband and vehicular slices compared to static proportional splitting. Subsequent research has extensively applied Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) for end-to-end network slicing orchestration. Dong et al. [

11] introduced a hierarchical DRL framework to jointly optimize inter-slice and intra-slice resource allocation, where a high-level agent periodically adjusts slice-wise resource partitions (allocating bandwidth or time slots to URLLC, eMBB, and mMTC slices) while lower-level agents handle user scheduling within each slice. By modeling the problem as a two-level Markov Decision Process (MDP), this approach learns to coordinate slicing decisions across different timescales, reducing queueing delays for latency-sensitive traffic while avoiding resource waste. Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL) has been explored to reflect the distributed nature of vehicular networks: Cui et al. [

12] presented a MARL-based slicing framework where each base station acts as an independent agent using multi-agent deep deterministic policy gradient algorithms to allocate local spectrum and computing resources. Li et al. [

13] developed a Deep Q-Network algorithm for multi-slice scenarios that jointly considers radio access and core network capacities to maximize user access rates. Machine learning has also enabled predictive slice provisioning: Abood et al. [

14] proposed a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)-based time-series prediction framework that forecasts each slice’s future resource demand from historical traffic patterns, enabling proactive resource reservation that improves utilization and maintains lower latency and higher reliability for vehicular services as mobility causes rapid load fluctuations.

Hybrid approaches combining optimization techniques with machine learning methods have emerged to address multifaceted challenges in vehicular network slicing. Khan et al. [

15] proposed a clustering-based slicing solution for highway scenarios that groups vehicles dynamically and assigns cluster leaders for Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V) relay communication in autonomous driving slices, while RSUs handle infotainment traffic via Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I) links, achieving low latency and high reliability for safety-critical messages through slice-aware resource partitioning. Recent work has explored hierarchical frameworks that decompose resource allocation across multiple decision layers. Qiao et al. [

16] developed a two-layer hierarchical learning approach where global inter-slice orchestration determines resource partitioning among slices while local intra-slice scheduling optimizes user-level allocation within each slice, employing proximal policy optimization to adapt to dynamic traffic patterns while satisfying heterogeneous QoS constraints. Cui et al. [

17] investigated hierarchical resource orchestration across distributed and centralized network units, coordinating spectrum and computing resource allocation to support multiple service types with differentiated QoS guarantees. Hazarika et al. [

18] extended hierarchical slicing to three tiers—first partitioning by 3GPP service class (URLLC/eMBB/mMTC), then by vehicle type, and finally by specific applications—integrating federated deep reinforcement learning to enable distributed learning across network nodes while preserving data privacy.

While these approaches have demonstrated significant progress, several opportunities exist to further enhance network slicing frameworks for vehicular communications. First, jointly optimizing slice selection and resource allocation decisions presents a promising direction beyond predetermined user-to-slice mappings. Rather than statically assigning all safety messages to a URLLC slice and all entertainment traffic to an eMBB slice, dynamic slice selection can better balance load distribution and improve system performance, particularly as vehicles generate mixed traffic with heterogeneous QoS requirements. Second, complementing learning-based methods with deterministic heuristics addresses distinct deployment scenarios and requirements. RL excels in long-term adaptation to evolving traffic patterns and network conditions, yet safety-critical vehicular applications such as cooperative platooning or collision avoidance that demand strict latency bounds (3GPP specifies 20 ms for certain safety applications) require algorithms with predictable real-time performance. Constructive heuristics can serve alongside learning-based approaches by providing deterministic response times without extensive training data or retraining when network conditions change abruptly, offering complementary reliability and stability for real-time vehicular slice control where execution time guarantees are paramount.

To explore these complementary opportunities, this study proposes a constructive heuristic algorithm that jointly optimizes slice selection and resource allocation across heterogeneous 5G base station and roadside unit infrastructure while guaranteeing deterministic execution within strict real-time constraints. The proposed algorithm employs a hierarchical allocation strategy, ensuring solution delivery within the 20 ms decision cycles required for V2X safety applications, while enabling dynamic slice selection to improve load balancing and system performance. This approach is designed to operate in conjunction with learning-based frameworks, providing fast, predictable decision-making for safety-critical scenarios, while learning-based methods can optimize long-term resource utilization and adaptation. The optimization model is presented in the following section.

3. Model Formulation

3.1. Problem Settings and Assumptions

This model addresses resource allocation on the network side of each slice in a V2X communication system. We consider a scenario where each user may request multiple services, with each service having specific QoS requirements. The resource allocation is performed periodically, and within each allocation cycle, the number of available 5G and RSU resource blocks for each slice is assumed to be known.

The key assumptions underlying this model are as follows:

Each user can simultaneously request multiple services with heterogeneous QoS demands.

Resource allocation decisions are made at regular intervals (allocation cycles).

The capacity of 5G and RSU resource blocks for each network slice is determined at the beginning of each cycle and remains constant throughout that cycle.

Services are assigned to network slices based on QoS compatibility, where a service can only be admitted to a slice if the slice’s QoS characteristics meet or exceed the service’s requirements.

Resource allocation follows a hierarchical strategy: 5G resource blocks are allocated first, and RSU resource blocks are utilized only when 5G resources are exhausted.

While the above assumptions simplify the problem for mathematical tractability, they are aligned with practical requirements in V2X systems. In particular, our formulation assumes fixed resource blocks and approximately static QoS requirements and service demands within one scheduling cycle. This approximation is justified because the scheduling interval is 20 ms, which is significantly shorter than the typical timescale of mobility-induced channel evolution and demand fluctuations in V2X scenarios. Therefore, within a 20 ms cycle, the demand and QoS requirements can be reasonably treated as quasi-static approximations for resource allocation decisions.

3.2. Mathematical Model

The notation used throughout this paper is summarized in

Table 1.

To demonstrate the model formulation, we present an illustrative example. Consider a scenario with two users (), where user 1 requests an autonomous driving service () with QoS requirements and ms, requiring RBs, and user 2 requests a video streaming service () with and ms, requiring RBs. The network provides three slices () with characteristics: URLLC (, ms, RBs, RBs) and eMBB (, ms, RBs, RBs).

The model first evaluates QoS compatibility: For user 1’s service, since , while because the eMBB slice cannot meet the 20 ms latency requirement. For user 2’s service, both and satisfy QoS compatibility.

Given priority weights , and transmission rates kbps/RB, kbps/RB, the model then determines: (1) slice assignments by solving , to maximize weighted throughput under constraint (10), ensuring each service accesses only one slice; (2) resource allocations RBs, RBs under constraints (7) and (8), meeting exact service demands; and (3) resource prioritation with and following the hierarchical allocation constraints (5) and (6), prioritizing 5G resources. The resulting weighted system throughput is kbps.

3.3. Model Description

The objective function (

1) maximizes the weighted system transmission rate (i.e., weighted throughput) across all users, services, and network slices. The priority weights

enable flexible differentiation among service classes and users. To prevent the long-term starvation of low-priority services, our framework relies on the dynamic configurability of these priority weights. Since the resource allocation executes every 20 ms, the central controller (e.g., the One Traffic Platform) can monitor the waiting time or rejection count of services. For temporal fairness, if a low-priority service (e.g., Infotainment) is rejected for multiple consecutive cycles, the platform can dynamically increase its weight in the next cycle. This “human-in-the-loop” or “platform-level” adjustment allows operators to balance the system between strict safety prioritization and long-term fairness, ensuring that even low-priority tasks eventually receive a resource window.

The model incorporates the following constraints:

Resource composition constraint (2): For each service admitted to a slice, the total allocated resource blocks must equal the sum of 5G and RSU resource blocks assigned to that service.

5G capacity constraint (3): The total number of 5G resource blocks allocated across all services within each slice cannot exceed the slice’s available 5G capacity.

RSU capacity constraint (4): Similarly, the total RSU resource blocks allocated within each slice must not exceed the slice’s RSU capacity.

Hierarchical allocation constraints (5) and (6): These constraints enforce the priority allocation strategy where 5G resources are fully utilized before RSU resources are deployed. Constraint (5) ensures RSU resources can only be used (i.e., ) when activated, while constraint (6) ensures that if RSU resources are not used (), the 5G capacity must be fully allocated.

Service demand satisfaction constraints (7) and (8): When a service is assigned to a slice (), the allocated resources must exactly match the service’s required resource blocks . If the service is not assigned to the slice (), no resources are allocated.

QoS matching constraint (9): A service can only be admitted to a slice if the slice’s QoS characteristics (reliability and latency) meet or exceed the service’s requirements, as indicated by .

Single slice assignment constraint (10): Each service of each user can be assigned to at most one network slice, preventing service duplication across slices.

Variable domain constraints (11)–(13): These constraints define the feasible domains for all decision variables, where resource allocations are non-negative integers and assignment indicators are binary.

4. Heuristic Algorithm for V2X Resource Allocation

Given the NP-hard nature of the resource allocation problem and the stringent real-time constraints in vehicular networks (20 ms decision cycles), we develop a novel constructive heuristic algorithm tailored to this problem. The algorithm operates in two main phases: (1) a first-phase allocation that determines service-to-slice assignments and performs resource distribution based on resource availability, and (2) a second-phase backfilling mechanism that leverages residual capacity to serve previously unallocated service requests.

4.1. Algorithm Overview

The proposed constructive heuristic algorithm consists of four key components:

Service-to-Slice Assignment: Determines which network slice each service request should access based on QoS compatibility and potential utility contribution.

Resource Scenario Detection: Analyzes resource availability within each slice to classify the allocation scenario and select the appropriate distribution strategy.

First-Phase Resource Allocation: Distributes 5G and RSU resource blocks to admitted services following prioritized strategies tailored to resource availability scenarios.

Second-Phase Backfilling: Attempts to serve initially rejected requests using residual capacity across all slices.

The algorithm ensures compliance with the constraint that 5G resource blocks must be allocated before RSU resources, exploiting the fact that in most cases, a single resource type suffices to satisfy user demands. This hierarchical allocation strategy maximizes utilization of the preferred 5G infrastructure while maintaining RSU resources as a supplementary capacity buffer.

Algorithm 1 presents the overall structure of the heuristic algorithm. For each scheduling cycle, the algorithm loads valid service requests (those satisfying QoS matching constraints), performs service-to-slice assignment, executes first-phase resource allocation for each slice, and conducts second-phase backfilling for unserved requests.

| Algorithm 1 Overall Heuristic Algorithm |

- 1:

procedure OverallHeuristicAlgorithm(, ) - 2:

Input: : Service dataset with detailed information about V2X service requests - 3:

Input: : Network slices dataset with capacity information - 4:

Output: Allocation results for each scheduling cycle with objective values - 5:

- 6:

for each scheduling cycle do - 7:

LoadValidServices ▹ - 8:

LoadSlices - 9:

ServicetoSliceAssignment - 10:

extract all user-service combinations from - 11:

- 12:

initialize from slice data - 13:

for all do - 14:

- 15:

if then - 16:

DetectResourceScenario - 17:

SliceResourceAllocation(assignedToSlice, s, scenario) - 18:

- 19:

Update - 20:

end if - 21:

end for - 22:

extract keys from - 23:

- 24:

if then - 25:

- 26:

Second-PhaseBackfilling - 27:

- 28:

end if - 29:

- 30:

- 31:

end for - 32:

return - 33:

end procedure

|

4.2. Service-to-Slice Assignment

The first critical step determines which service requests should be admitted to which network slices. The algorithm processes only combinations where , ensuring satisfaction of the QoS matching constraint—services can only access slices whose QoS characteristics meet or exceed their requirements.

Since the hierarchical allocation strategy prioritizes 5G resources before RSU resources, and in most scenarios only one resource type suffices to satisfy service demands, we evaluate each service-slice combination using two complementary perspectives. For each valid

combination, we first compute the absolute throughput contribution under each resource type:

These scores represent the weighted throughput contribution if the service is fully satisfied using only 5G or only RSU resources, respectively. We then derive the per-resource-block efficiency by dividing by the required resource blocks:

These efficiency metrics quantify the weighted throughput gain per resource block consumed, enabling comparison of services with different resource demands.

To establish allocation priorities, we construct two aggregate metrics for each service-slice combination:

The metric selects the maximum absolute throughput contribution achievable using either resource type, representing the service’s potential value to system performance. The metric selects the maximum per-resource-block efficiency, favoring services that deliver high throughput gains relative to their resource consumption.

The algorithm performs a two-level sorting of all valid service-slice combinations: primary sorting by in descending order (prioritizing high-value services), with ties broken by in descending order (favoring resource-efficient services). This hierarchical sorting balances maximizing absolute system throughput while promoting efficient resource utilization.

To satisfy constraint (10) (), the algorithm retains only the highest-scored combination for each unique pair, eliminating duplicate slice assignments for the same service. This greedy selection yields the initial service-to-slice assignment for the first allocation phase.

Algorithm 2 formalizes this procedure, evaluating all QoS-compatible slices for each service, computing utility metrics, performing two-level sorting, and selecting unique assignments.

| Algorithm 2 Service to Slice Assignment |

- 1:

procedure ServicetoSliceAssignment() - 2:

- 3:

for each unique service in do - 4:

GetValidSlicesForService(, u, i) - 5:

for each option do - 6:

▹ Unified resource requirement - 7:

- 8:

- 9:

- 10:

- 11:

- 12:

- 13:

end for - 14:

end for - 15:

Sort by in descending order - 16:

- 17:

- 18:

for each do - 19:

if then - 20:

- 21:

- 22:

end if - 23:

end for - 24:

return - 25:

end procedure

|

4.3. Resource Scenario Detection and Allocation Strategies

Following service-to-slice assignment, the algorithm examines resource availability within each slice to determine the appropriate allocation strategy. For each slice

k, we compute the ratio of available 5G capacity to total demand from assigned services:

where

denotes the set of services assigned to slice

k. Based on this ratio, two distinct resource scenarios are identified:

Abundant 5G Scenario (): Sufficient 5G resources exist to satisfy all service demands without activating RSU resources.

Limited 5G/RSU Scenario (): 5G resources are insufficient, necessitating strategic allocation of both 5G and RSU resource blocks.

Algorithm 3 presents the resource scenario detection procedure, which computes the capacity-to-demand ratio and determines the appropriate allocation strategy.

| Algorithm 3 Detect Resource Scenario |

- 1:

procedure DetectResourceScenario(, ) - 2:

- 3:

- 4:

- 5:

- 6:

if then - 7:

return - 8:

else - 9:

return - 10:

end if - 11:

end procedure

|

Based on the detected scenario, Algorithm 4 dispatches to the appropriate allocation strategy.

| Algorithm 4 Slice Resource Allocation |

- 1:

procedure SliceResourceAllocation(, , ) - 2:

- 3:

- 4:

- 5:

if then - 6:

return Abundant5G(, , , ) - 7:

else - 8:

return 5G/RSUStrategy(, , , ) - 9:

end if - 10:

end procedure

|

4.3.1. Abundant 5G Allocation Strategy

When 5G resources are abundant, the algorithm employs a simple on-demand allocation strategy. Since the model constraints prioritize 5G resource allocation and no RSU activation is required, each service receives exactly its required number of 5G resource blocks: and . This straightforward approach maximizes resource utilization while ensuring service reliability.

Algorithm 5 details the abundant 5G allocation procedure. Services are sorted by their total utility contribution, and resources are allocated on demand until capacity is exhausted.

| Algorithm 5 Abundant 5G Resource Allocation |

- 1:

procedure Abundant5GResourceAllocation(, , , ) - 2:

▹ 5G allocation per service - 3:

▹ Service activation - 4:

- 5:

Sort by in descending order - 6:

for each service i in sorted do - 7:

- 8:

if and then - 9:

- 10:

- 11:

- 12:

end if - 13:

end for - 14:

▹ No RSU - 15:

- 16:

- 17:

for each service i in do - 18:

if then - 19:

- 20:

- 21:

allocationresults - 22:

- 23:

end if - 24:

end for - 25:

return - 26:

end procedure

|

4.3.2. Limited 5G/RSU Allocation Strategy

For scenarios where 5G capacity is insufficient, a more sophisticated three-step allocation strategy is employed:

Step 1: 5G Resource Prioritization. The algorithm first computes a 5G utility contribution score for each service to establish allocation priority:

Services within the same slice are sorted in descending order by , with ties broken by ascending resource demand . This ordering prioritizes services with high weighted transmission rates per resource block. The algorithm then allocates 5G resources following this priority sequence, assigning requested amounts on demand until 5G capacity is exhausted. The last service in the priority queue receives any remaining fractional 5G capacity, ensuring complete utilization of 5G resources.

Step 2: Priority Restructuring for RSU Allocation. After 5G allocation, services fall into two categories: those partially satisfied (received some 5G resources but not the full required amount) and those completely unserved (received no 5G resources). The algorithm restructures priorities for RSU allocation:

Step 3: RSU Resource Distribution. The algorithm first allocates RSU resources to high-priority services (those with partial 5G satisfaction) in order, filling their residual demands. Once all high-priority demands are satisfied or RSU capacity is exhausted, remaining RSU resources are distributed to low-priority services following descending order, with ties broken by ascending demand. This two-tier priority mechanism ensures that services already receiving partial allocations are completed before initiating new service admissions, improving QoS satisfaction rates.

Algorithm 6 implements the complete limited 5G/RSU allocation strategy, incorporating all three steps described above.

| Algorithm 6 5G/RSU Strategy for Limited Resources |

- 1:

procedure 5G/RSUHStrategy(, , , ) - 2:

▹ 5G allocation per service - 3:

▹ RSU allocation per service - 4:

▹ Service activation - 5:

- 6:

- 7:

- 8:

for each service i in do - 9:

if then - 10:

- 11:

- 12:

end if - 13:

end for - 14:

Sort by descending, then by ascending - 15:

for each candidate in do - 16:

if then - 17:

- 18:

- 19:

- 20:

- 21:

end if - 22:

end for - 23:

- 24:

for each service i in do - 25:

if and and then - 26:

- 27:

- 28:

- 29:

end if - 30:

end for - 31:

for each service i in do - 32:

if and then - 33:

- 34:

- 35:

end if - 36:

end for - 37:

Sort by priority, then by descending, then by ascending - 38:

for each candidate in do - 39:

if then - 40:

- 41:

- 42:

- 43:

end if - 44:

end for - 45:

if else 0 - 46:

- 47:

for each service i in do - 48:

- 49:

if and then - 50:

▹ Deactivate if not fully satisfied - 51:

end if - 52:

ifthen - 53:

- 54:

- 55:

allocationresults - 56:

- 57:

end if - 58:

end for - 59:

return - 60:

end procedure

|

4.4. Second-Phase Backfilling Allocation

The greedy nature of the initial service-to-slice assignment may cause some services to be rejected even though alternative slices with residual capacity could accommodate them. To exploit remaining resources and improve system throughput, the algorithm implements a second-phase backfilling mechanism.

This phase considers all unserved services from the first phase and constructs candidate combinations with all feasible slices (those satisfying QoS compatibility constraints). Each candidate combination is evaluated using the previously defined sorting score , and combinations are processed in descending score order. For each candidate:

Check if the target slice’s total available capacity (sum of the remaining 5G and RSU resources) can satisfy the service’s demand.

If sufficient capacity exists, allocate resources following the hierarchical strategy: first allocate 5G resources up to availability or demand, then supplement with RSU resources if needed.

Update the slice’s remaining capacity immediately after allocation.

If insufficient capacity exists, proceed to the next highest-scored candidate combination.

This backfilling process continues until all unserved services are either allocated or no feasible candidate combinations remain. By revisiting rejected services and considering alternative slice assignments, the second phase significantly improves resource utilization and system performance.

Algorithm 7 formalizes the second-phase backfilling procedure, which evaluates unserved services against all compatible slices and allocates resources hierarchically when sufficient capacity exists.

| Algorithm 7 Second-Phase Backfilling Allocation |

- 1:

procedure Second-PhaseBackfilling(, ) - 2:

- 3:

- 4:

filter valid data where - 5:

for each option o in do - 6:

- 7:

- 8:

- 9:

- 10:

- 11:

create candidate with service and utility information - 12:

- 13:

end for - 14:

if then - 15:

return - 16:

end if - 17:

Sort by in descending order - 18:

- 19:

for each candidate c in do - 20:

- 21:

if then - 22:

continue - 23:

end if - 24:

- 25:

- 26:

- 27:

- 28:

if then - 29:

if then - 30:

- 31:

else if then - 32:

- 33:

- 34:

else - 35:

- 36:

end if - 37:

else - 38:

continue ▹ Cannot satisfy full request - 39:

end if - 40:

- 41:

create allocation record with assignment details - 42:

- 43:

- 44:

- 45:

- 46:

end for - 47:

return - 48:

end procedure

|

4.5. Complexity Analysis

To evaluate the scalability of the proposed constructive heuristic, we analyze its computational and memory complexity. Let denote the number of users, the maximum number of services per user, and the number of network slices.

4.5.1. Computational Complexity

The computational complexity of each algorithm component is analyzed as follows:

Service-to-Slice Assignment (Algorithm 2): The algorithm evaluates all valid combinations satisfying the QoS matching constraint in time. Subsequently, sorting these combinations by utility and efficiency metrics requires operations.

First-Phase Allocation (Algorithms 5 and 6): For each slice k, the algorithm sorts the assigned services by their utility scores, requiring time, where denotes the number of services assigned to slice k. Summing over all slices yields a total complexity of .

Second-Phase Backfilling (Algorithm 7): In the worst case, the algorithm evaluates all unserved services against all compatible slices, constructing and sorting candidate combinations, resulting in a complexity of .

The overall computational complexity is dominated by the sorting operations, yielding . This polynomial complexity ensures efficient scalability as the number of users and slices increases, making the algorithm suitable for real-time vehicular network resource allocation.

4.5.2. Memory Complexity

The algorithm maintains data structures for service requests, slice capacities, candidate combinations, and allocation results. The primary memory consumption arises from storing the candidate service-slice combinations and the final allocation decisions, which scales as . For typical V2X deployment scenarios (for instance, 700 concurrent users, each requesting up to 3 services across 5 network slices), the memory footprint is approximately 1–2 MB, ensuring practical feasibility for deployment on resource-constrained vehicular platforms.

5. Numerical Experiments

This section evaluates the proposed constructive heuristic algorithm through comprehensive experiments designed to assess three critical performance dimensions: solution quality, computational efficiency, and scalability. The experimental framework encompasses two resource availability scenarios (abundant 5G and limited 5G requiring coordinated 5G-RSU allocation), four comparative baseline methods (Gurobi solver, Round-Robin, Random allocation, and Simulated Annealing), and realistic V2X workloads with nine heterogeneous service types distributed across five network slices serving varying user populations. The evaluation begins with a comparative analysis between Gurobi optimal solutions and Random baseline to quantify the fundamental value of intelligent resource allocation, followed by comprehensive baseline performance comparisons and scalability analysis across varying user densities. These experiments aim to validate the algorithm’s capability to deliver near-optimal resource allocation decisions within strict real-time constraints mandated by safety-critical vehicular applications, while demonstrating robust performance across diverse operational conditions.

5.1. Data Generation Methodology

To ensure realistic experimental evaluation, we employ a systematic data generation framework that synthesizes network slice characteristics, user service demands, and resource transmission rates based on 3GPP technical specifications [

8] and V2X application requirements.

5.1.1. Network Slice Configuration

The experimental framework instantiates five heterogeneous network slices spanning the complete spectrum of V2X QoS requirements, as detailed in

Table 2. URLLC_1 represents the most stringent slice with ultra-high reliability of 0.99999 and extremely low latency of 1ms. URLLC_2 provides slightly relaxed but still critical performance with 0.9999 reliability and 10 ms latency. eMBB_1 delivers high-throughput connectivity with 0.999 reliability and 20 ms latency. eMBB_2 offers moderate performance with 0.99 reliability and 50 ms latency. Finally, mMTC supports massive connectivity with 0.95 reliability and 100 ms latency.

Each slice exhibits heterogeneous transmission rate characteristics for 5G base station and RSU resource blocks. As shown in

Table 3, URLLC_1 and URLLC_2 provide transmission rates uniformly sampled from 300 to 600 kbps for 5G resources and 150 to 350 kbps for RSU resources per block. eMBB_1 and eMBB_2 support higher rates from 500 to 900 kbps for 5G blocks and 250 to 500 kbps for RSU blocks. The mMTC slice operates at reduced rates from 200 to 400 kbps for 5G resources and 100 to 250 kbps for RSU resources.

5.1.2. User Service Demand Generation

The experimental framework simulates 500 concurrent vehicular users, each requesting one to three heterogeneous V2X services. Service count distribution follows a realistic traffic pattern: 60% of users request a single service, 30% request two services, and 10% request three services, modeling varying application complexity across vehicle types such as basic sedans versus autonomous vehicles with multiple active safety systems.

We define nine distinct V2X service types with diverse QoS requirements, as detailed in

Table 4. Each service type is characterized by specific reliability and latency constraints, priority weight ranges, and resource block demand ranges that govern slice compatibility and resource allocation decisions. EmergencyBrake represents the most stringent service with ultra-high reliability of 0.9999 and 5 ms latency, priority weights ranging from 8 to 10, and resource demands between 1 and 3 blocks, making it compatible only with the highest-performance URLLC slices. CollisionAvoidance and TrafficSignalControl provide critical safety functions with 0.999 reliability at 20 ms and 15 ms latency, respectively, using priority weights from 6 to 9 and 7 to 9, with moderate resource demands. PlatooningControl maintains similar reliability requirements at 25 ms latency with priority weights from 5 to 8 and demands from 3 to 8 blocks for coordinated vehicle movement. SensorSharing and HDMapUpdate operate at 0.99 reliability with 50 ms and 100 ms latencies, using priority weights from 4 to 7 and 2 to 5, and resource demands from 5 to 12 and 10 to 25 blocks, respectively, reflecting bandwidth-intensive data exchange requirements. WeatherAlert and RemoteDiagnostics provide informational services with relaxed reliability of 0.97 and 0.96 at 150 ms and 180 ms latencies, priority weights from 3 to 6 and 2 to 5, and moderate resource demands. Infotainment represents the least critical service with 0.95 reliability at 200 ms latency, the lowest priority weights from 1 to 3, and demands from 8 to 20 blocks for entertainment content delivery.

Each user randomly selects services with equal selection probability across all nine service types, ensuring unbiased workload distribution. For each selected service, the system randomly samples specific reliability and latency requirements within tolerance bounds (e.g., ±2% for reliability, ±10% for latency) to introduce realistic QoS variability while maintaining service type characteristics. Priority weights and resource block demands are uniformly sampled from their respective ranges. This perturbation mechanism models the heterogeneity of real-world vehicular environments where identical service types exhibit slight variations due to vehicle mobility, channel conditions, and application configurations. Critically, each user’s service requirements remain fixed across all network slices and do not change between scheduling cycles, ensuring consistent QoS contract enforcement regardless of the assigned slice. This design reflects practical network slicing principles where service level agreements (SLAs) are established per user rather than per slice.

5.1.3. Resource Capacity Configuration

The two experimental scenarios employ distinct resource capacity configurations to evaluate algorithm behavior under varying infrastructure conditions:

Abundant 5G Scenario: Base station capacity is set sufficiently high to accommodate all service demands using only 5G resources, eliminating the need for RSU activation. This models urban areas with dense macro-cell deployments where infrastructure investment prioritizes cellular coverage. RSU capacity remains available but unused, serving as backup infrastructure.

Table 5 presents the detailed resource configuration across ten scheduling cycles, i.e., Transmission Time Intervals (TTIs) 0–9 for the abundant 5G scenario. Each cycle uses a different random seed (0, 10, 20, …, 90) to generate service demand patterns, with 500 concurrent users requesting 3660–3810 services per cycle. Total service demand ranges from 19,851 to 22,265 resource blocks, while available 5G capacity is fixed at 50,000 resource blocks per cycle across all five network slices (10,000 blocks per slice). RSU capacity is limited to 500 resource blocks (100 blocks per slice) to model backup infrastructure. The resulting capacity-to-demand ratios range from 2.27 to 2.54, ensuring that 5G resources alone can satisfy all service requests without RSU activation.

Limited 5G Scenario: Base station capacity is intentionally constrained to approximately 4.5–5.0% of total service demand, necessitating coordinated 5G-RSU resource management. This reflects severely capacity-constrained highway environments where roadside units augment sparse cellular coverage.

Table 6 presents the detailed resource configuration across ten scheduling cycles (TTIs 0–9) for the limited 5G scenario. Each cycle uses a different random seed (0, 10, 20, …, 90) to generate service demand patterns, with 500 concurrent users requesting 3660–3810 services per cycle. Total service demand ranges from 19,851 to 22,265 resource blocks, while available 5G capacity is severely limited to 500 resource blocks per cycle across all five network slices (100 blocks per slice). RSU capacity provides an additional 500 resource blocks (100 blocks per slice) as supplementary infrastructure. The resulting capacity-to-demand ratios range from 0.045 to 0.050 (4.5–5.0%), creating a highly resource-limited environment that requires strategic resource allocation to maximize system performance.

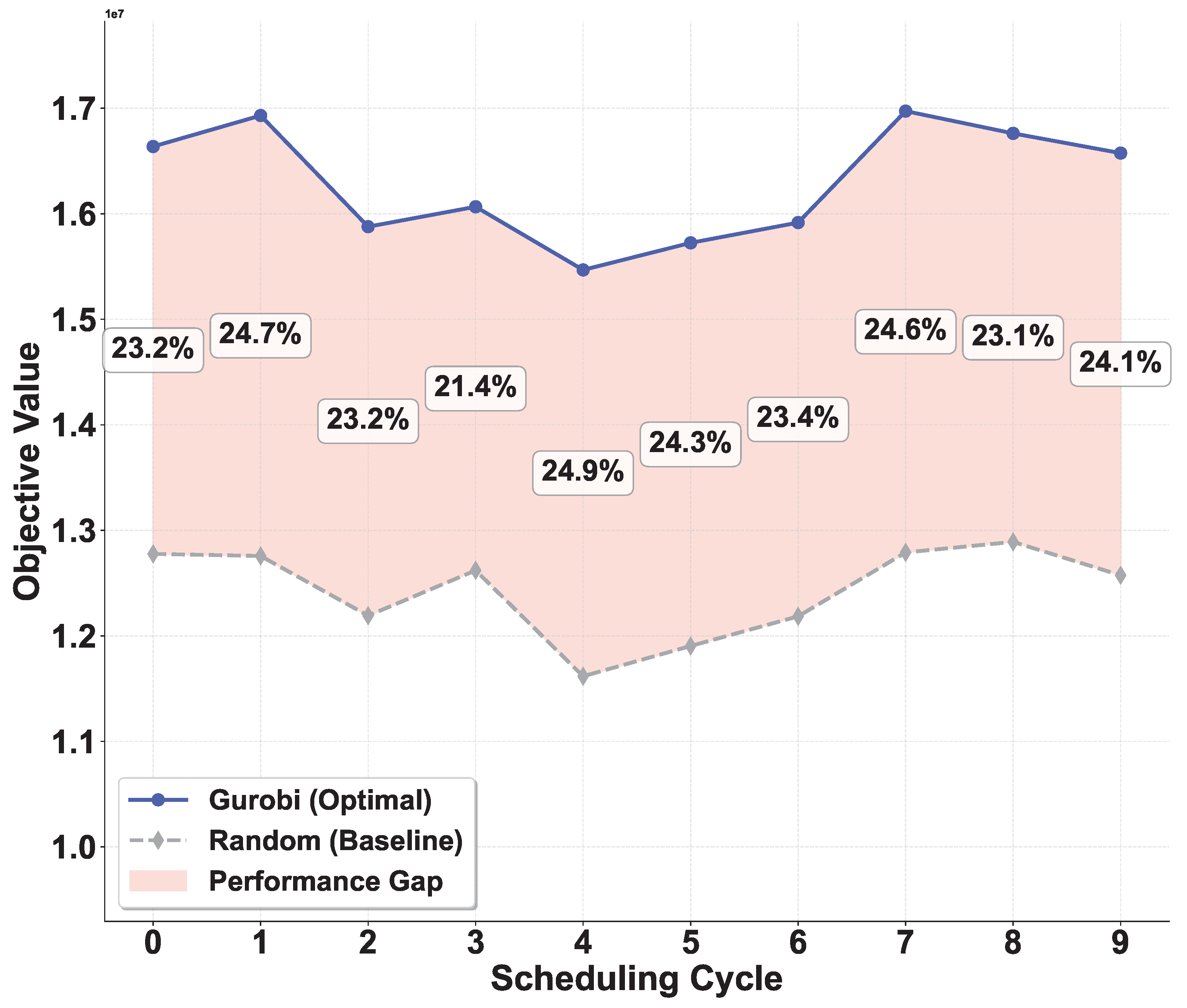

5.2. Comparative Performance Analysis: Gurobi vs. Random Baseline

To establish the fundamental value of our optimization model, we compare the Gurobi optimal solution with a random allocation baseline across both resource scenarios as shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

The Random baseline serves as a fundamental performance benchmark representing allocation decisions made without optimization. This baseline randomly shuffles the sequence of service requests and processes them in arbitrary order. For each service, the algorithm randomly selects a QoS-compatible network slice from those with sufficient remaining resource block capacity. Resource allocation within the selected slice follows the same hierarchical 5G-priority strategy: first exhausting available 5G resource blocks before utilizing RSU resource blocks.

In the abundant 5G scenario, Gurobi achieves objective values of approximately

to

, while the Random baseline attains

to

. From

Figure 2, we can see a 21.4% to 24.9% performance gap between Gurobi optimal and Random baseline in each scheduling cycle.

Under limited 5G scenario, Gurobi achieves objective values of approximately

to

, while the Random baseline attains an approximately

to

objective value. From

Figure 3, there is a 42.5% to 51.0% performance gap between Gurobi optimal and Random baseline in each scheduling cycle.

These results validate the value of our optimization model as it can increase weighted system throughput compared to arbitrary allocation.

5.3. Algorithm Performance Evaluation and Comparison

This subsection compares algorithm performance under a fixed population of 500 users across both resource scenarios, focusing on solution quality, computational efficiency, and service admission characteristics.

5.3.1. Solution Quality and Computational Time

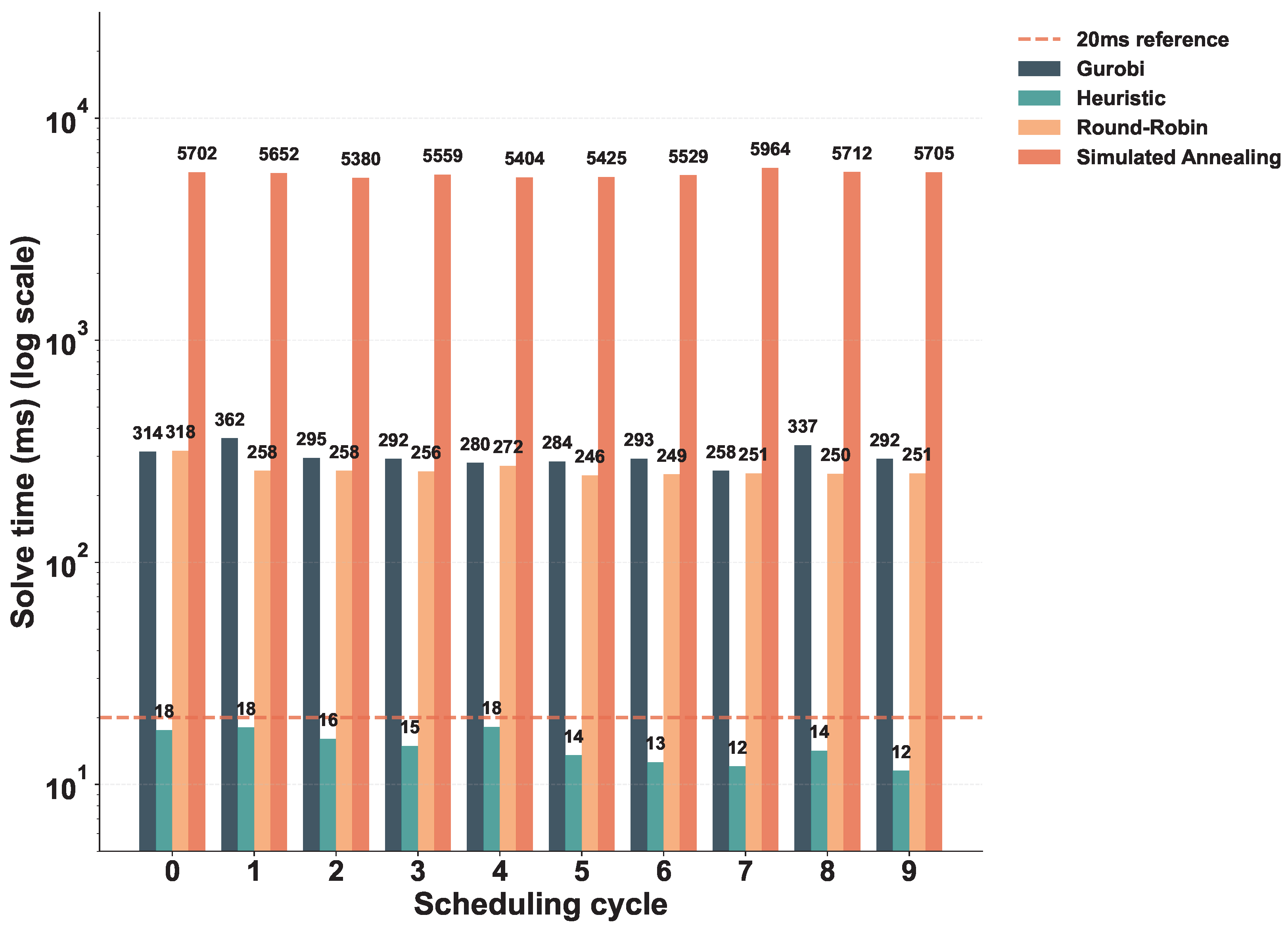

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 present a comprehensive comparison of optimality gaps and computational times across all evaluated algorithms. In the abundant 5G scenario (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5),

Figure 4 shows that both the proposed constructive heuristic and Simulated Annealing achieve optimal solutions across all ten scheduling cycles (TTI 0–9), matching Gurobi’s performance. In contrast, Round-Robin exhibits 22.9–25.2% optimality gaps.

Figure 5 analyzes computational time performance across all evaluated algorithms. The proposed constructive heuristic consistently executes within 12–18 ms across all scheduling cycles, safely meeting the 3GPP-mandated 20 ms real-time requirement for vehicular networks. Gurobi requires 258–337 ms per cycle, while Simulated Annealing demands 5380–5964 ms. Round-Robin executes within 250–318 ms and exhibits 22.9–25.2% optimality gaps, demonstrating that neither computational efficiency nor solution quality can match the proposed constructive heuristic.

In the limited 5G scenario (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7),

Figure 6 shows the proposed constructive heuristic maintains optimality gaps between 3.5% and 5.7% across all scheduling cycles. Simulated Annealing maintains gaps ranging from 10.1% to 12.3%, while Round-Robin’s performance deteriorates dramatically, with gaps ranging from 48.7% to 56.5%.

Figure 7 shows the proposed constructive heuristic executes within 13–17 ms, Gurobi requires 365–519 ms, Simulated Annealing demands 6250–6774 ms, and Round-Robin takes 237–286 ms.

5.3.2. Service Admission Success Rates

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 analyze service admission success rates. In the abundant 5G scenario (

Figure 8), all algorithms achieve nearly 100% admission rates, as available capacity substantially exceeds demand.

Figure 9 reveals the proposed constructive heuristic’s superiority under limited resources, achieving the highest admission rates of 31–35%, exceeding even Gurobi’s optimal solution. Simulated Annealing achieves 30–34% admission rates, while Round-Robin manages only 15–19%, demonstrating roughly half the performance of the proposed constructive heuristic.

5.4. Scalability Analysis

This subsection examines algorithm scalability as user density increases from 400 to 700 concurrent users under the limited 5G scenario. This stress-test configuration evaluates whether algorithms maintain performance characteristics as network load intensifies, analyzing computational time, solution quality, service admission, and objective values.

5.4.1. Computational Time and Solution Quality Scalability

Figure 10 presents computational time evolution across user densities on a logarithmic scale. As user count increases from 400 to 700, all algorithms exhibit longer execution times. The proposed constructive heuristic maintains execution times between 13 ms and 18 ms, remaining below the 20 ms real-time threshold. Gurobi’s execution time grows from 324 ms to 476 ms, Simulated Annealing ranges from 4925 ms to 8079 ms, and Round-Robin ranges from 184 ms to 312 ms.

Figure 11 analyzes solution quality evolution across user densities. As user count increases from 400 to 700, Round-Robin’s optimality gaps increase from 50.9% to 54.3%. Simulated Annealing maintains relatively stable gaps between 10.9% and 11.7%. The proposed constructive heuristic shows decreasing gaps from 5.3% to 3.4%, remaining within 5.5% across all densities.

5.4.2. Service Admission and Objective Value Scalability

Figure 12 shows allocated services as user density increases from 400 to 700. The proposed constructive heuristic allocates 2385 services at 400 users, growing to 2622 services at 700 users, which is approximately a 10% increase. The heuristic tracks Gurobi’s allocation, which ranges from 2355 to 2584 services, with both showing saturation as the system reaches resource limits. Simulated Annealing allocates between 2285 and 2484 services. Round-Robin allocates fewer services, ranging from 1280 to 1351, about half the heuristic’s performance, wasting significant resource capacity.

Figure 13 presents objective value evolution across 400–700 users. The proposed heuristic grows from

to

, Gurobi from

to

, Simulated Annealing from

to

, while Round-Robin remains nearly flat at

–

.

The scalability analysis demonstrates three key findings: (1) Computational efficiency: the proposed heuristic maintains 13–18 ms execution time across all user densities, enabling real-time deployment; (2) Solution quality: it achieves 3.4–5.3% optimality gaps under limited resources, outperforming baseline heuristics; (3) Performance across user densities: the proposed heuristic achieves the highest service admission count, while Gurobi attains the maximum system transmission rate throughput, with the heuristic ranking second and both significantly outperforming other baseline algorithms.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This study addresses the challenge of real-time and efficient resource allocation for multi-slice V2X networks under heterogeneous QoS requirements. By formulating a joint slice selection and resource allocation model as an integer programming problem, the proposed framework captures both the differentiated service demands of vehicular users and the hierarchical nature of 5G and RSU resources. To achieve real-time feasibility, a constructive heuristic algorithm is developed, featuring a hierarchical allocation strategy that prioritizes 5G resources, followed by RSU resource backfilling. This design enables efficient utilization of heterogeneous network resources while ensuring latency constraints are satisfied within the stringent 20 ms limit required for vehicular communication.

Comprehensive numerical experiments validate the effectiveness and practicality of the proposed approach. In both abundant and limited 5G resource scenarios, the heuristic achieves near-optimal performance, outperforming baseline methods such as Random, Simulated Annealing, and Round-Robin in terms of weighted system throughput and service admission rate. The algorithm consistently maintains execution times under 20 ms, confirming its suitability for delay-sensitive V2X applications. Moreover, scalability analysis demonstrates that the performance gap between the heuristic and optimal Gurobi solutions narrows as the number of users increases, further highlighting the method’s robustness and adaptability to large-scale vehicular networks.

Despite the promising results, this work is currently limited to single-cell scenarios with finite traffic loads and slice sets. Future research will address these limitations and expand the framework in several directions: (i) extending the heuristic to multi-cell environments to handle inter-cell interference and coordinated resource orchestration; (ii) evaluating performance under significantly higher traffic loads and larger slice sets, including a more exhaustive analysis of memory and computational overheads; (iii) incorporating predictive traffic and mobility intelligence for proactive capacity reservation; (iv) co-optimizing radio, edge-compute, and network function resources for end-to-end service chains; and (v) embedding machine learning techniques, such as RL, to enhance decision-making in dynamic vehicular environments.