Isotonic and Convex Regression: A Review of Theory, Algorithms, and Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. QP Formulation for Isotonic Regression When

1.2. QP Formulation for Convex Regression When

1.3. Scope, Motivation, and Organization of the Review

1.4. Notation and Definitions

2. The Basic QP Formulation

2.1. Isotonic Regression When

2.2. Convex Regression When

3. Isotonic Regression

3.1. Statistical Properties

3.1.1. Univariate Case

3.1.2. Multivariate Case

3.2. Computational Algorithms

3.3. Applications

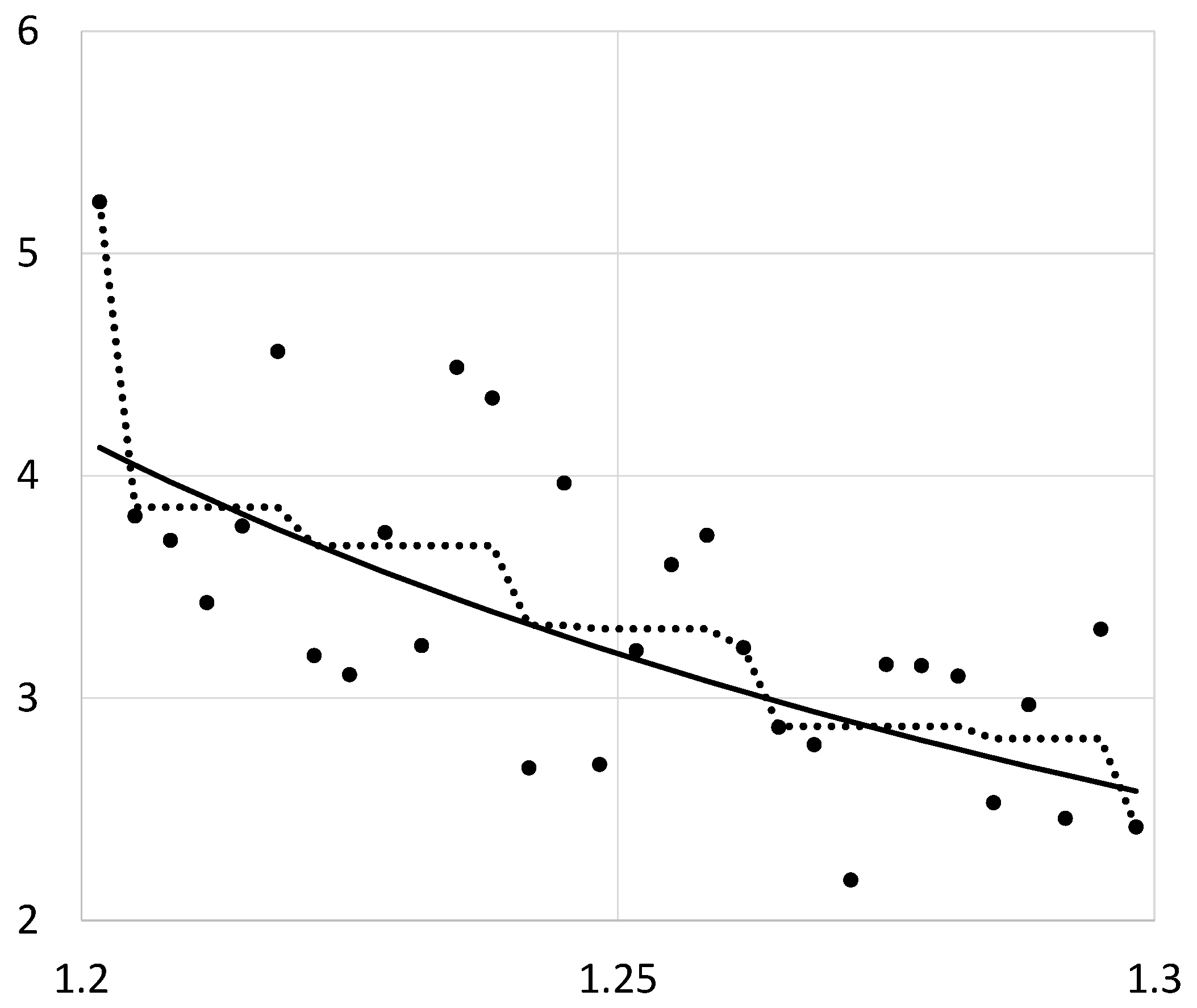

Illustration of Isotonic Regression

3.4. Challenges

3.4.1. Non-Smoothness of Isotonic Regression

3.4.2. Overfitting of Isotonic Regression

4. Convex Regression

4.1. Statistical Properties

4.1.1. Univariate Case

4.1.2. Multivariate Case

4.2. Computational Algorithms

4.3. Applications

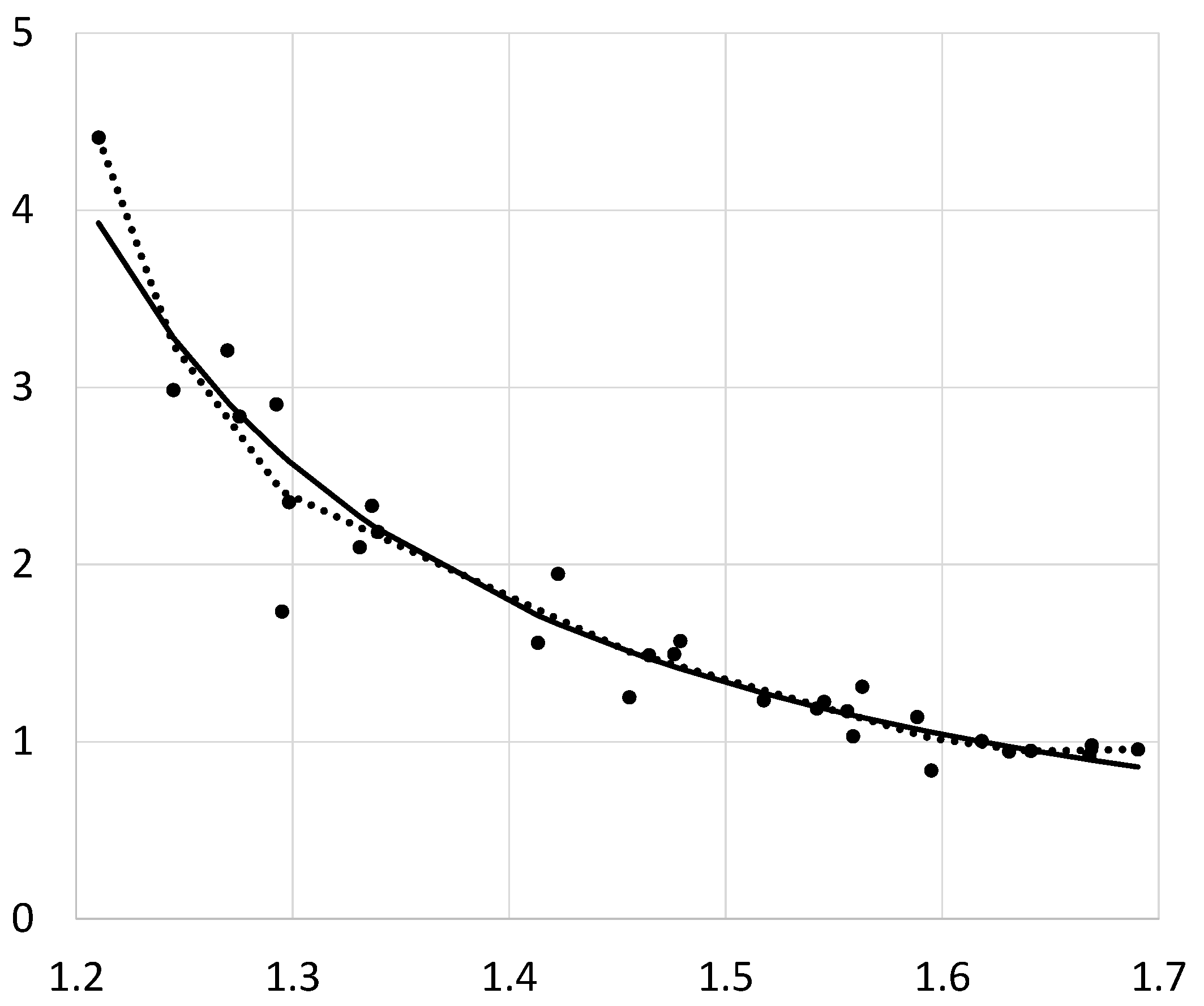

Illustration of Convex Regression

4.4. Challenges

4.4.1. Non-Smoothness of Convex Regression

4.4.2. Overfitting of Convex Regression

5. Connections to Contemporary Machine Learning

6. Future Directions

6.1. Problem 1—Scalable Algorithms for Large-Scale Data

6.2. Problem 2—Algorithms for Multivariate Isotonic Regression

6.3. Problem 3—Pointwise Limit Distribution of Multivariate Convex Regression

6.4. Problem 4—Incorporating Smoothness into Shape-Restricted Regression in Multiple Dimensions

6.5. Problem 5—Overfitting in Isotonic and Convex Regression

6.6. Problem 6—Theory for Penalized Isotonic and Convex Regression

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brunk, H.D. Maximum likelihood estimates of monotone parameters. Ann. Math. Stat. 1955, 26, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildreth, C. Point estimates of ordinates of concave functions. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1954, 49, 598–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guntuboyina, A.; Sen, B. Nonparametric Shape-Restricted Regression. Stat. Sci. 2018, 33, 568–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.L.; Jiang, D.R. Shape Constraints in Economics and Operations Research. Stat. Sci. 2018, 33, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S.; Vandenberghe, L. Convex Optimization; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brunk, H.D. On the estimation of parameters restricted by inequalities. Ann. Math. Stat. 1958, 29, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunk, H.D. Estimation of isotonic regression. In Nonparametric Techniques in Statistical Inference; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1970; pp. 177–195. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, M.; Woodroofe, M. On the degrees of freedom in shape-restricted regression. Ann. Stat. 2000, 28, 1083–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.H. Risk bounds in isotornic regression. Ann. Stat. 2002, 30, 528–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E. The Limiting Behavior of Isotonic and Convex Regression Estimators When The Model Is Misspecified. Electron. J. Stat. 2020, 14, 2053–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, P.; Dhar, S.S. A study on the least squares estimator of multivariate isotonic regression function. Scand. J. Stat. 2020, 47, 1192–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Wang, T.; Chatterjee, S.; Samworth, R.J. Isotonic Regression in General Dimensions. Ann. Stat. 2019, 47, 2440–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, R.E.; Bartholomew, R.J.; Bremner, J.M.; Brunk, H.D. Statistical Inference Under Order Restrictions; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Mukerjee, H. Monotone nonparametric regression. Ann. Stat. 1988, 16, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammen, E. Estimating a smooth monotone regression function. Ann. Stat. 1991, 19, 724–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Tibshirani, R. The monotone smoothing of scatterplots. Technometrics 1984, 26, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, J.O. Monotone regression splines in action. Stat. Sci. 1988, 3, 425–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.; Huang, L.S. Nonparametric kernel regression subject to monotonicity constraints. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 624–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, F. An algorithm for monotone regression with one or more independent variables. Biometrika 1970, 57, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykstra, R.L.; Robertson, T. An algorithm for isotonic regression for two or more independent variables. Ann. Stat. 1982, 10, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.I.C. The min-max algorithm and isotonic regression. Ann. Stat. 1983, 11, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Eddy, W.F. An algorithm for isotonic regression on ordered rectangular grids. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 1996, 5, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallant, A.; Golub, G.H. Imposing curvature restrictions on flexible functional forms. J. Econ. 1984, 26, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzkin, R.L. Restrictions of economic theory in nonparametric methods. In Handbook of Econometrics; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; Volume IV, pp. 2523–2558. [Google Scholar]

- Aït-Sahalia, Y.; Duarte, J. Nonparametric option pricing under shape restrictions. J. Econom. 2003, 116, 9–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, R.R. A note on waiting times in single server queues. Oper. Res. 1983, 31, 950–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moolchan, E.T.; Hudson, D.L.; Schroeder, J.R.; Sehnert, S.S. Heart rate and blood pressure responses to tobacco smoking among African-American adolescents. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2004, 96, 767. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Shi, P. Monotone B-spline smoothing. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1998, 93, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammen, E.; Thomas-Agnan, C. Smoothing splines and shapre restrictions. Scand. J. Stat. 1999, 26, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.C. Inference using shape-restricted regression splines. Ann. Stat. 2008, 2, 1013–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dette, H.; Scheder, R. Strictly Monotone and Smooth Nonparametric Regression for Two or More Variables. Can. J. Stat. 2006, 34, 535–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E. An estimator for isotonic regression with boundary consistency. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2025, 226, 110513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Meyer, M.C.; Opsomer, J.D. Penalized isotonic regression. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2015, 161, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luss, R.; Rosset, S. Bounded isotonic regression. Electron. J. Stat. 2017, 11, 4488–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, D.L.; Pledger, G. Consistency in concave regression. Ann. Stat. 1976, 4, 1038–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammen, E. Nonparametric regression under qualitative smoothness assumptions. Ann. Stat. 1991, 19, 741–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeneboom, P.; Jongbloed, G.; Wellner, J.A. Estimation of a convex function: Characterizations and Asymptotic Theory. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1653–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S. An improved global risk bound in concave regression. Electron. J. Stat. 2016, 10, 1608–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allon, G.; Beenstock, M.; Hackman, S.; Passy, U.; Shapiro, A. Nonparametric estimatrion of concave production technologies by entropy. J. Appl. Econom. 2007, 22, 795–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seijo, E.; Sen, B. Nonparametric least squares estimation of a multivariate convex regression function. Ann. Stat. 2011, 39, 1633–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.; Glynn, P.W. Consistency of Multi-dmentional Convex Regression. Oper. Res. 2012, 60, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E. On convergence rates of convex regression in multiple dimensions. INFORMS J. Comput. 2014, 26, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Wellner, J.A. Multivariate convex regression: Global risk bounds and adaptation. arXiv 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, W. A note on least squares fitting of function constrained to be either non-negative, nondecreasing, or convex. Manag. Sci. 1973, 20, 130–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykstra, R.L. An algorithm for restricted least squares regression. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1983, 78, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.F. Some algorithms for concave and isotonic regression. TIMS Stud. Manag. Sci. 1982, 19, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, D.A.S.; Massam, H. A mixed primal-dual bases algorithm for regression under inequality constraints. Application to concave regression. Scand. J. Stat. 1989, 16, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, R.; Iyengar, A.C.G.; Sen, B. A Computational Framework for Multivariate Convex Regression and Its Variants. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2019, 114, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, A.; Boyd, S. Convex piecewise-linear fitting. Optim. Eng. 2009, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, N.; Forzani, L.; Morin, P. On uniform consistent estimators for convex regression. J. Nonparametr. Stat. 2011, 23, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, L.A.; Dunson, D.B. Multivariate Convex Regression with Adaptive Partitioning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2013, 14, 3261–3294. [Google Scholar]

- Bertsimas, D.; Mundru, N. Sparse Convex Regression. INFORMS J. Comput. 2021, 33, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Lim, E. On consistency of absolute deviations estimators of convex functions. Int. J. Stat. Probab. 2016, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varian, H.R. The nonparametric approach to demand analysis. Econometrica 1982, 50, 945–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varian, H.R. The nonparametric approach to production analysis. Econometrica 1984, 52, 579–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, I.; Tzitziris, P. Infant mortality and economic growth: Modeling by increasing returns and least squares. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering, London, UK, 5–7 July 2017; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Birke, M.; Dette, H. Estimating a convex function in nonparametric regression. Scand. J. Stat. 2007, 34, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Parmeter, C.F.; Racine, J.S. Nonparametric kernel regression with multiple predictors and multiple shape constraints. Stat. Sin. 2013, 23, 1347–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal, P.; Sen, B. On univariate convex regression. Sankhya A 2017, 79, 215–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lin, Q.; Sen, B. On degrees of freedom of projection estimators with applications to multivariate nonparametric regression. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2020, 115, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E. Convex Regression with a Penalty. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.19788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, B.; Kolter, J.Z. Input Convex Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning; PMLR Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Dimension | Design | Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAV algorithm [13] | Ordered | ||

| Graphical/cumulative sum | Ordered | ||

| General QP solvers | Any d | Any | Polynomial |

| Grid-based methods | Grid | – |

| Method | Dimension | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| QP formulation [2] | Exact solution | |

| Iterative projection [45] | Guaranteed convergence | |

| Standard multivariate QP [39] | Severe computational burden | |

| Augmented Lagrangian [48] | Scales to | |

| Cutting-plane methods [52] | Handles | |

| Hyperplane approximation | Approximate estimator |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lim, E. Isotonic and Convex Regression: A Review of Theory, Algorithms, and Applications. Mathematics 2026, 14, 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010147

Lim E. Isotonic and Convex Regression: A Review of Theory, Algorithms, and Applications. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):147. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010147

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Eunji. 2026. "Isotonic and Convex Regression: A Review of Theory, Algorithms, and Applications" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010147

APA StyleLim, E. (2026). Isotonic and Convex Regression: A Review of Theory, Algorithms, and Applications. Mathematics, 14(1), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010147