Research on Intelligent Traffic Signal Control Based on Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Redefine the reinforcement learning model in the context of multi-agent signal optimization, incorporating the concepts of clustered sequences and Nash equilibrium to improve the design of states and rewards, thereby enhancing model performance.

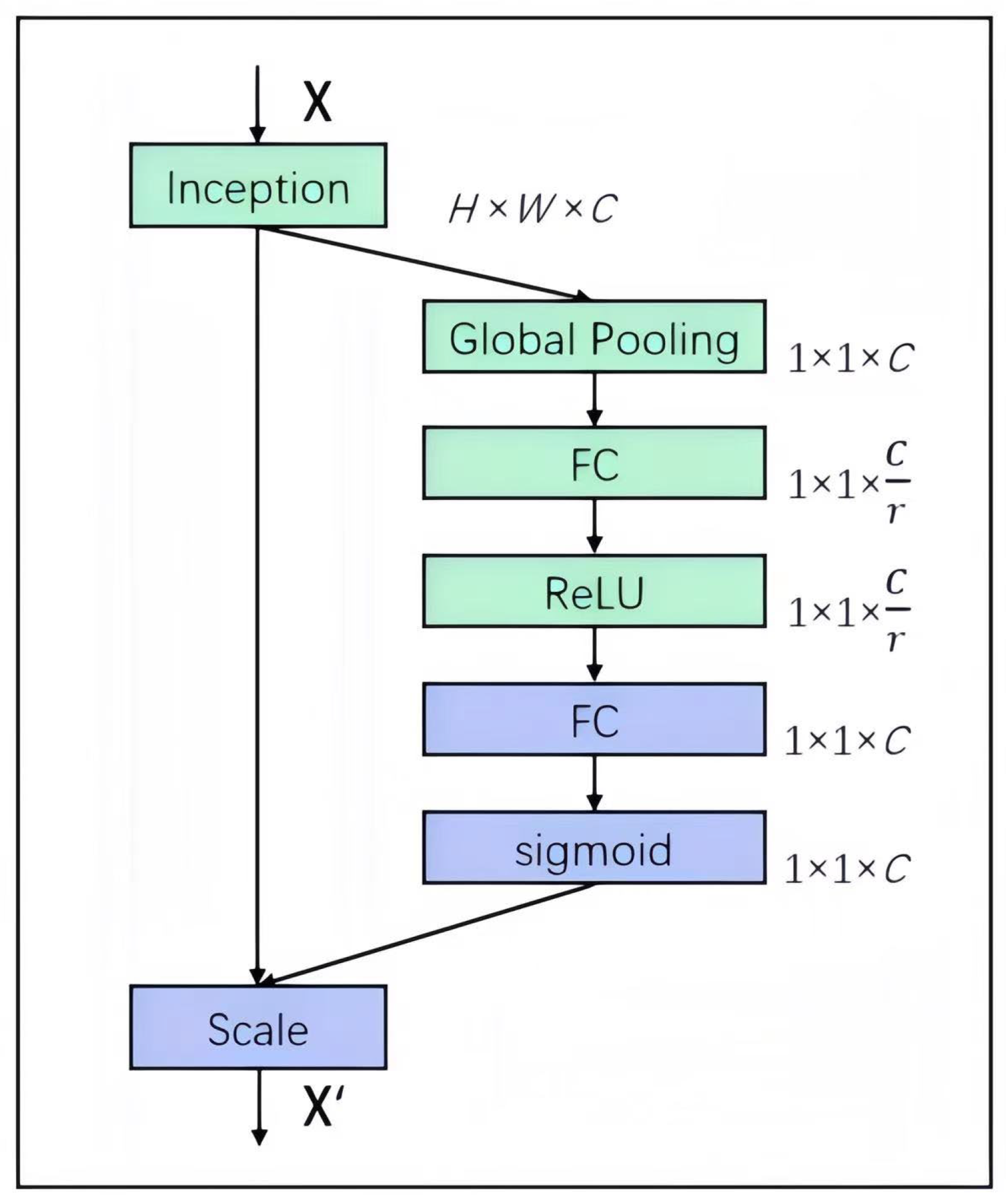

- Leverage an attention mechanism to enhance the neural network’s adaptability to feature channels, improving overall model performance.

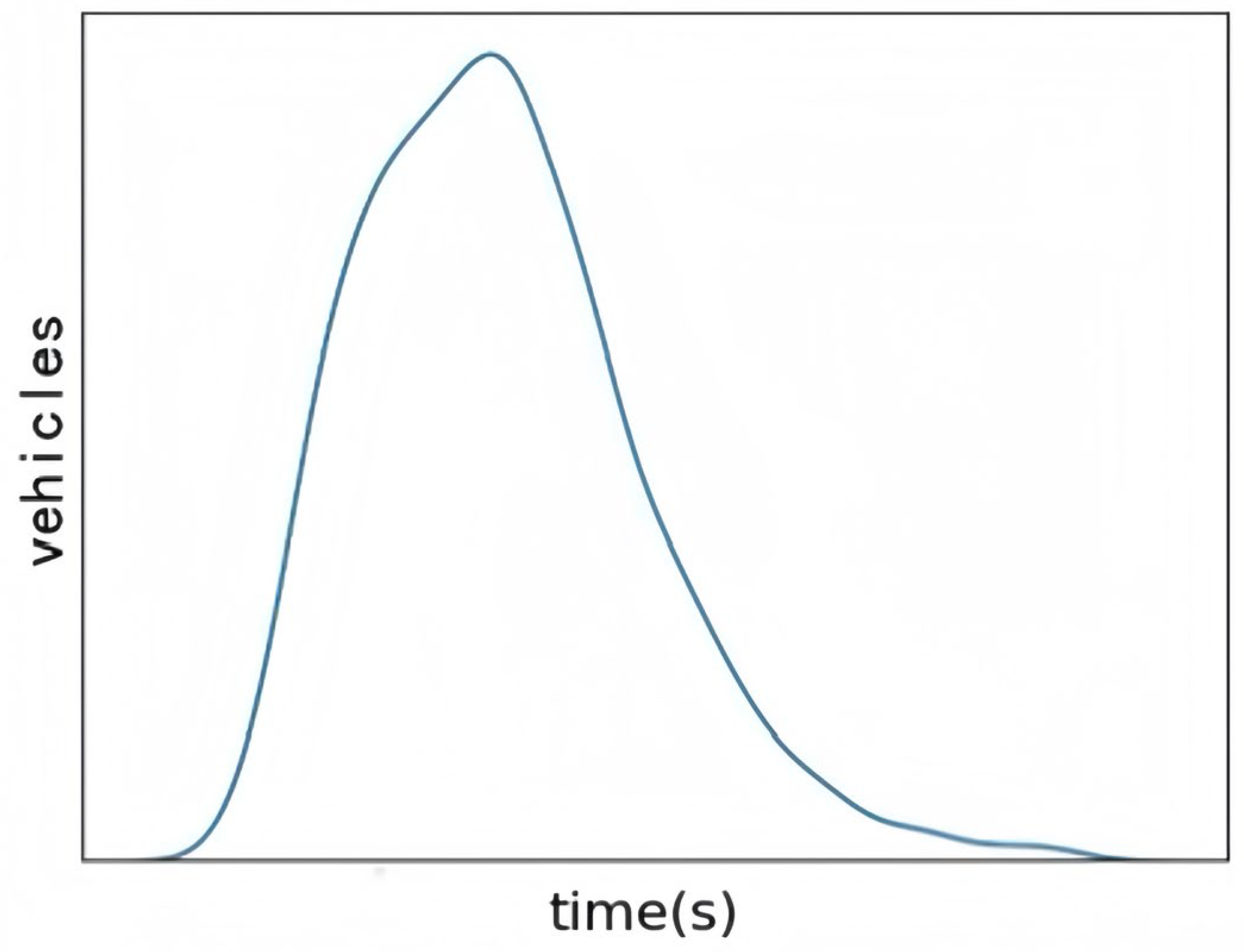

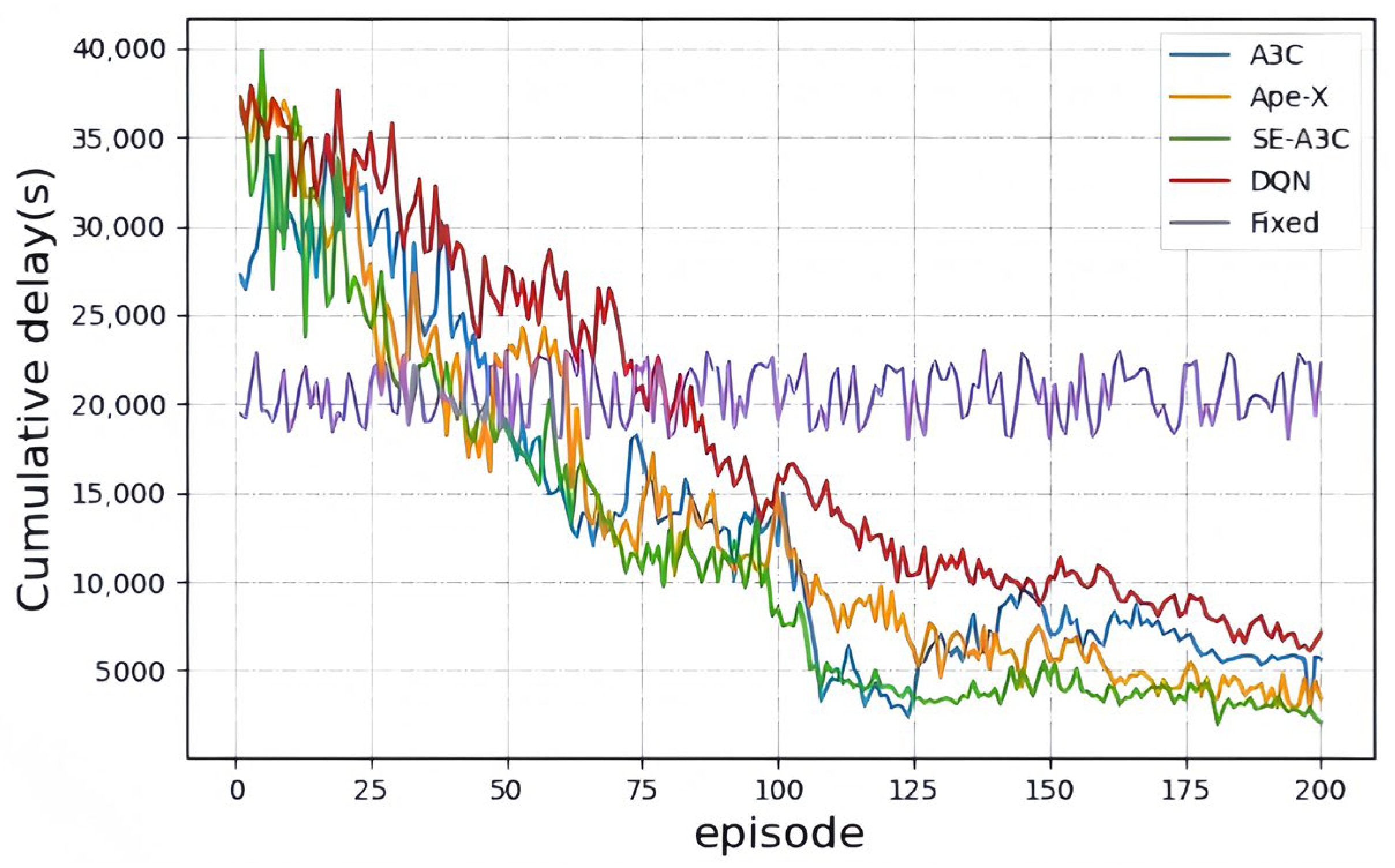

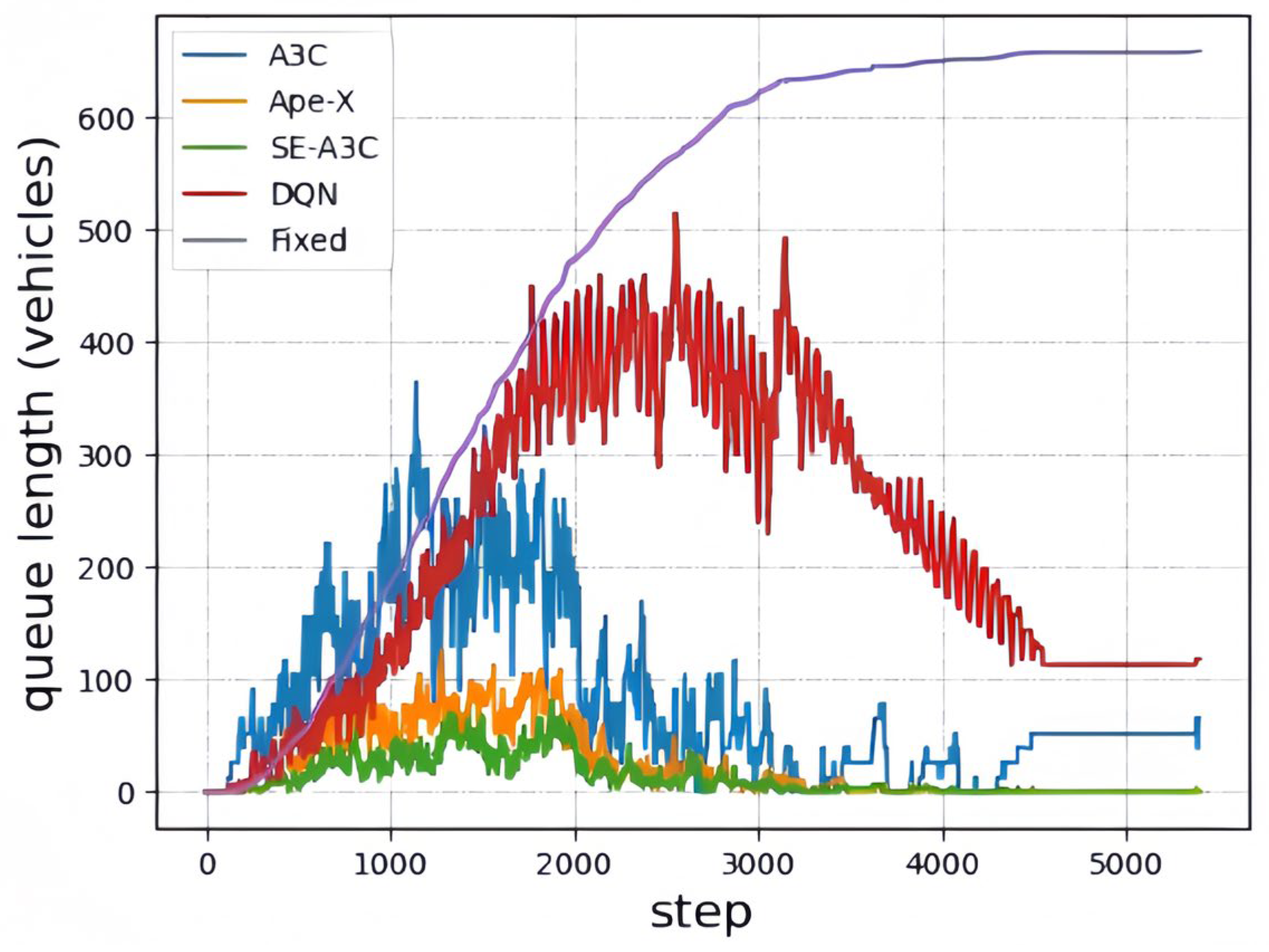

- Utilize the SUMO 1.14.1 simulation software to create various intersection scenarios, selecting the average vehicle queue length and cumulative queue time as performance evaluation metrics. Vehicle generation is modeled using the Weibull distribution to better reflect real-world traffic conditions.

2. Related Work

3. Traffic Signal Control Model

3.1. State

3.2. Action

3.3. Reward

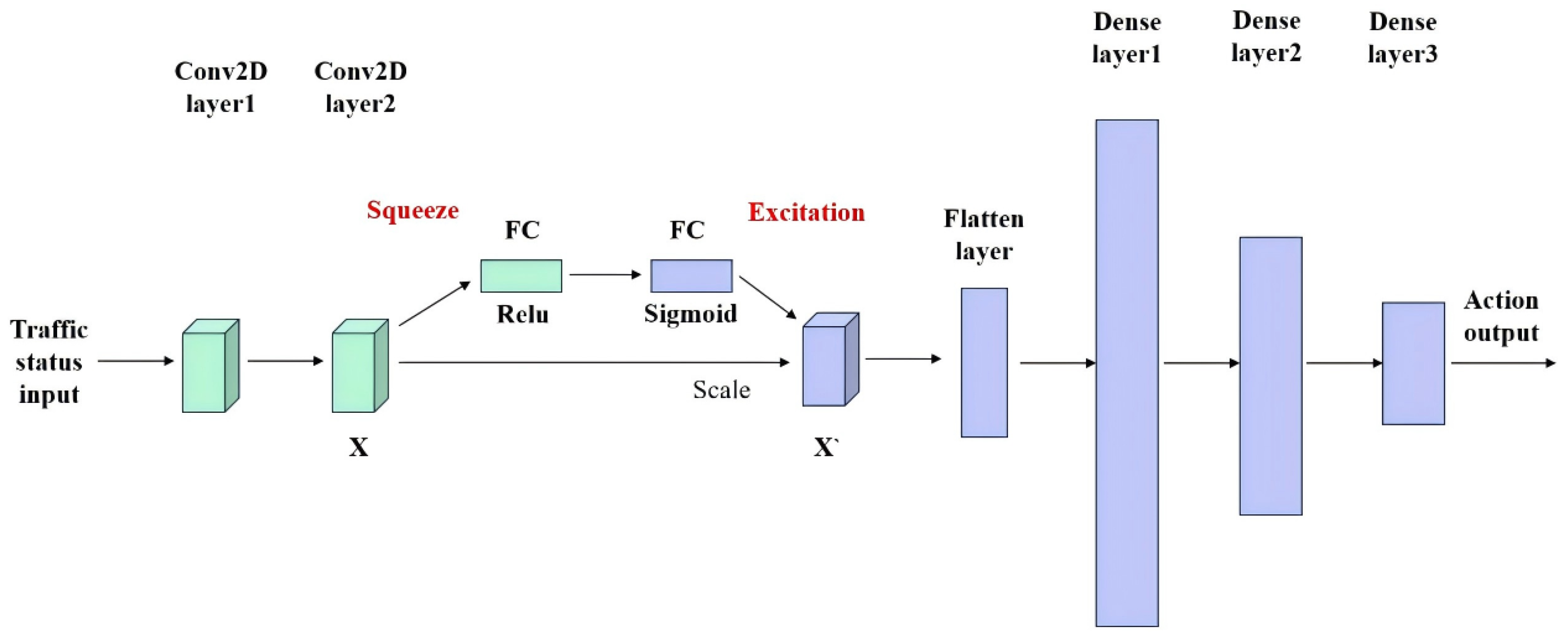

3.4. SE Module

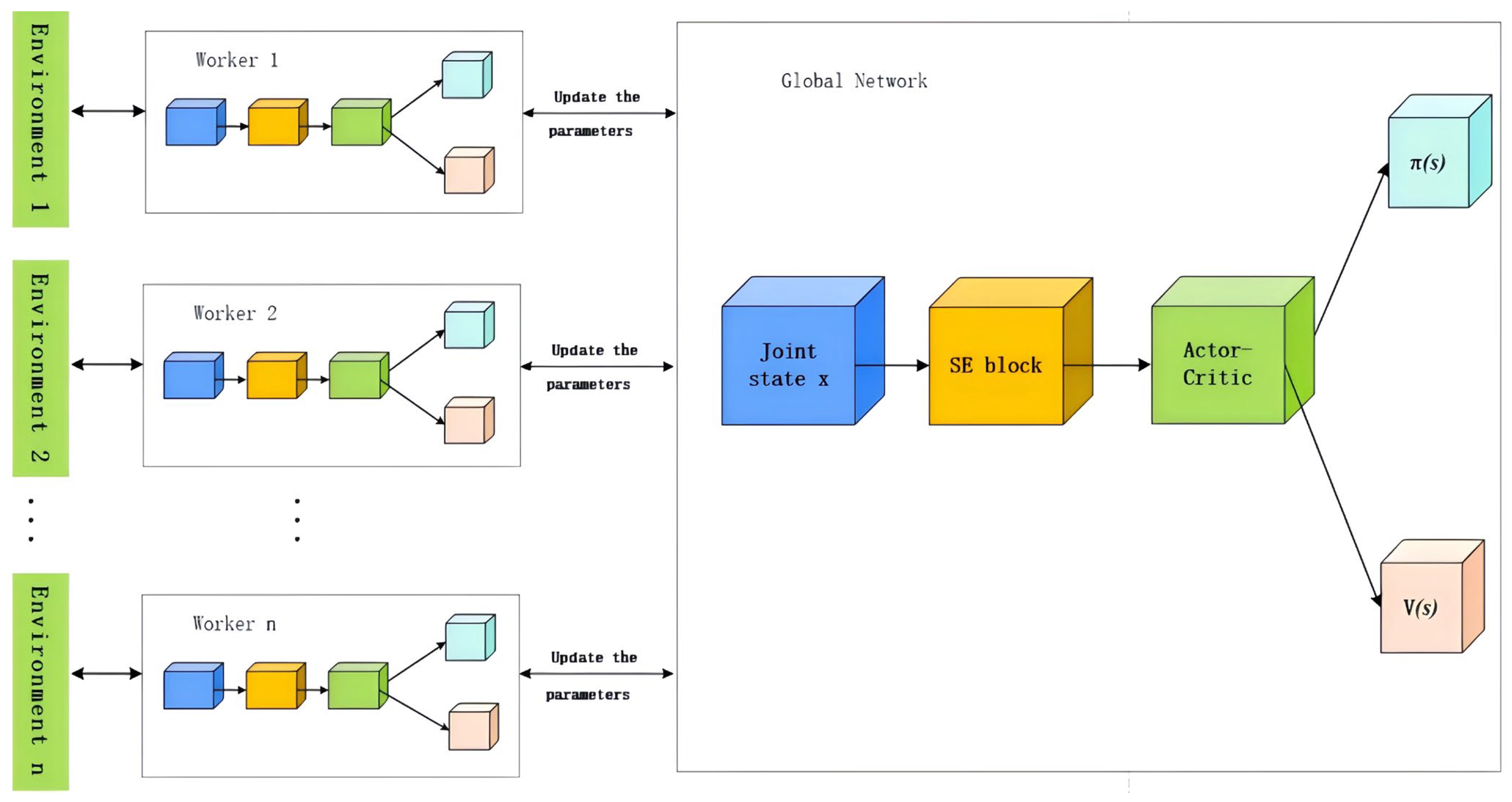

3.5. A3C Algorithm

| Algorithm 1 SE-A3C algorithm |

| 1: Input |

| Initialize training rounds episodes, single agent training duration tmax, single agent training steps per round t = 1, total training steps T = 1 |

| Initialize global Actor network parameters θ, Global Critical Network Parameters θv. Single agent Actor network parameters θ′, Single agent Critical network parameters θ′v |

| Initialize learning rate α, Discount factor γ, Learning Strategy Probability ε. |

| 2: Repeat |

| 3: Initialize gradient: dθ = 0 and dθV = 0 4: Synchronize agent network parameters θ′ = θ and θ′v = θv |

| 5: Divide the lanes into groups to obtain the state st |

| 6: Repeat |

| 7: Selecting action at based on Actor network 8: Execute action at to obtain new state st+1 and reward rt |

| 9: t = t +1 |

| 10: T = T + 1 |

| 11: Until reaching the final state st or t = tmax |

| 12: for i ∈ {t, …, tmax} do 13: R = ri + γR |

| 14: Cumulative gradient |

| 15: Cumulative gradient |

| 16: End for 17: Use gradient formula to perform asynchronous updates and update global network parameters θ and θv |

| 18: End |

3.6. Architectural Analysis of SE-A3C Based on the A3C Baseline

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Experimental Environment

4.2. Experimental Setup

4.3. Experimental Results and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yue, W.; Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Duan, P.; Mao, G. What is the root cause of congestion in urban traffic networks: Road infrastructure or signal control? IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 8662–8679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zheng, G.; Gayah, V.; Li, Z. Recent advances in reinforcement learning for traffic signal control: A survey of models and evaluation. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2021, 22, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sanner, S.; Abdulhai, B. A critical review of traffic signal control and a novel unified view of reinforcement learning and model predictive control approaches for adaptive traffic signal control. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.14426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zheng, G.; Yao, H.; Li, Z. IntelliLight: A reinforcement learning approach for intelligent traffic light control. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, London, UK, 19–23 August 2018; pp. 2496–2505. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, G.; Xiong, Y.; Zang, X.; Feng, J.; Wei, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Xu, K.; Li, Z. Learning phase competition for traffic signal control. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Beijing China, 3–7 November 2019; pp. 1963–1972. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, G.; Zang, X.; Xu, N.; Wei, H.; Yu, Z.; Gayah, V.; Xu, K.; Li, Z. Diagnosing reinforcement learning for traffic signal control. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.04716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronauer, S.; Diepold, K. Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning: A survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 895–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampuu, A.; Matiisen, T.; Kodelja, D.; Kuzovkin, I.; Korjus, K.; Aru, J.; Aru, J.; Vicente, R. Multiagent cooperation and competition with deep reinforcement learning. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Zeng, K.; Wang, J.; Sharma, P.K.; Ma, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, S. BERT-based deep spatial-temporal network for taxi demand prediction. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 9442–9454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanis, S.; Samson, L.; Bloembergen, D.; Bakker, T. Back to Basics: Deep Reinforcement Learning in Traffic Signal Control. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Leal, P.; Kartal, B.; Taylor, M.E. Is multiagent deep reinforcement learning the answer or the question? A brief survey. arXiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Duan, L.; Jiang, G.; Sfarra, S.; Zhang, H.; Jung, H. Optimization Control of Adaptive Traffic Signal with Deep Reinforcement Learning. Electronics 2024, 13, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokade, R.; Jin, X.; Amato, C. Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning Based on Representational Communication for Large-Scale Traffic Signal Control. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 47646–47658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, M.; Typaldos, P.; Papageorgiou, M. Lane-free signal-free intersection crossing via model predictive control. Control Eng. Pract. 2025, 154, 106115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekzadeh, M.; Papamichail, I.; Papageorgiou, M.; Bogenberger, K. Optimal internal boundary control of lane-free automated vehicle traffic. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 126, 103060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Fukushima, N.; Yang, B.; Wang, Z.; Takata, T.; Nagasawa, H.; Nakano, K. Reinforcement Learning-Based Intelligent Traffic Signal Control Considering Sensing Information of Railway. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 31125–31136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Chen, Y.; Kumar, B.V.D. Regional Intelligent Traffic Signal Control System Based on Multi-agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th International Conference on Computer and Communication Systems (ICCCS), Guangzhou, China, 21–23 April 2023; pp. 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yan, C.; Li, X.; Fang, L.; Wu, Y.-J.; Li, J. Distributed Signal Control of Arterial Corridors Using Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. 2023, 24, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.; Elhadef, M.; Khan, M.U.G. Collaborative Traffic Signal Automation Using Deep Q-Learning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 136015–136032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Flocco, D.; Azarm, S.; Balachandran, B. Deep Reinforcement Learning for the Co-Optimization of Vehicular Flow Direction Design and Signal Control Policy for a Road Network. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 7247–7261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Ye, D.; Zhu, T.; Zhou, W. Location-Based Real-Time Updated Advising Method for Traffic Signal Control. IEEE IoT J. 2024, 11, 14551–14562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, X.; Song, Y.; Liu, X. Network-Wide Traffic Signal Control Based on MARL with Hierarchical Nash-Stackelberg Game Model. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 145085–145100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Ni, W. An Enhanced Dueling Double Deep Q-Network with Convolutional Block Attention Module for Traffic Signal Optimization in Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 44224–44232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Wang, P.; Li, S. Traffic Signal Control with Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Intelligent Computing, Automation and Systems (ICICAS), Chongqing, China, 6–8 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Albanie, S.; Sun, G.; Wu, E. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 42, 2011–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sewak, M. Actor-Critic Models and the A3C: The Asynchronous Advantage Actor-Critic Model. In Deep Reinforcement Learning; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, H.; Zhang, Y.; Damani, M.; Sartoretti, G. SocialLight: Distributed Cooperation Learning towards Network-Wide Traffic Signal Control. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems (AAMAS), Auckland, New Zealand, 9–13 May 2022; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Wu, J.; Shen, J.; Yong, B.; Zhou, Q. An Edge Based Multi-Agent Auto Communication Method for Traffic Light Control. Sensors 2020, 20, 4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zai, W.; Yang, D. Improved Deep Reinforcement Learning for Intelligent Traffic Signal Control Using ECA_LSTM Network. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailidis, P.; Michailidis, I.; Lazaridis, C.R.; Kosmatopoulos, E. Traffic Signal Control via Reinforcement Learning: A Review on Applications and Innovations. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinne, H. The Weibull Distribution a Handbook; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | A3C (Classical Baseline) | SE-A3C (Proposed) | A3C with Modified Critic Structure | A3C with Explicit Communication | A3C with Spatio-Temporal Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning Paradigm | Asynchronous Actor-Critic | Asynchronous Actor-Critic | Asynchronous Actor-Critic | Asynchronous Actor-Critic | Asynchronous Actor-Critic |

| Critic Design | Fully decentralized | Decentralized with coordination constraint | Locally centralized/neighborhood-conditioned [27] | Decentralized | Decentralized or partially centralized |

| State Representation | Local intersection state | Grouped structured local state | Local + neighboring state | Local + communicated information [28] | Temporal sequences with spatial relations [29] |

| Feature Modeling Strategy | Uniform processing | Channel-wise recalibration (SE) | Shared feature encoding | Message-based aggregation | Recurrent encoding + graph aggregation |

| Temporal Modeling | Optional | Lightweight sequential grouping | Optional | Optional | LSTM/GRU-based modeling [29] |

| Multi-Agent Coordination | Implicit | Constraint-based consistency | Critic-level coordination | Explicit communication [28] | Graph-based spatial coordination |

| Training Stability | Standard A3C updates | Structural constraints | Improved value estimation | Stabilized via communication | Enhanced via structured modeling |

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of training rounds episodes | 200 |

| Number of training steps per round steps | 5400 |

| Batch size | 20 |

| Weibull distribution shape Parameter k | 2 |

| Learning Rate | 0.001 |

| Discount Factory | 0.75 |

| Green light duration | 12 |

| Yellow light duration | 4 |

| 0.8 | |

| 0.2 |

| Accumulated Rewards | Average Number of Queued Vehicles | Accumulated Queuing Time | Number of Vehicles After Testing | The Number of Steps for Neural Network Convergence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A3C | −34,500.3 | 267.1 | 5650 | 65 | 3300 |

| Ape-X | −20,630.5 | 233.6 | 3399 | 0 | 2400 |

| SE-A3C | −14,990.8 | 221.5 | 2079 | 0 | 2100 |

| DQN | −42,631.2 | 265.0 | 7086 | 118 | - |

| Fixed | - | 293.5 | 22,673 | 659 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cao, K.; Yang, S.; Yang, C.; Yu, M.; Geng, J.; Jung, H. Research on Intelligent Traffic Signal Control Based on Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. Mathematics 2026, 14, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010149

Cao K, Yang S, Yang C, Yu M, Geng J, Jung H. Research on Intelligent Traffic Signal Control Based on Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010149

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Kerang, Siqi Yang, Cheng Yang, Mingxu Yu, Jietan Geng, and Hoekyung Jung. 2026. "Research on Intelligent Traffic Signal Control Based on Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010149

APA StyleCao, K., Yang, S., Yang, C., Yu, M., Geng, J., & Jung, H. (2026). Research on Intelligent Traffic Signal Control Based on Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. Mathematics, 14(1), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010149