3.1. Probabilistic Wind Power with FL

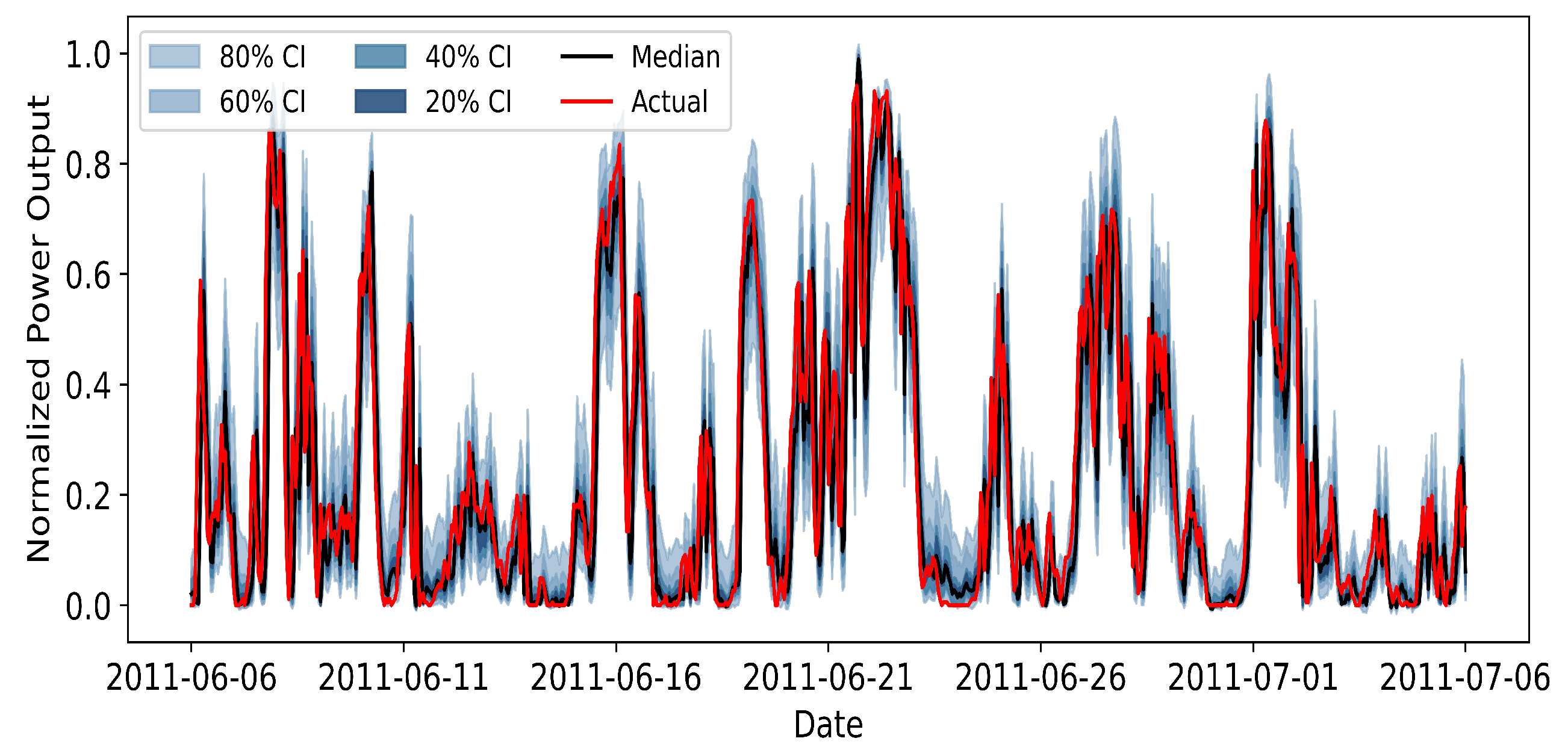

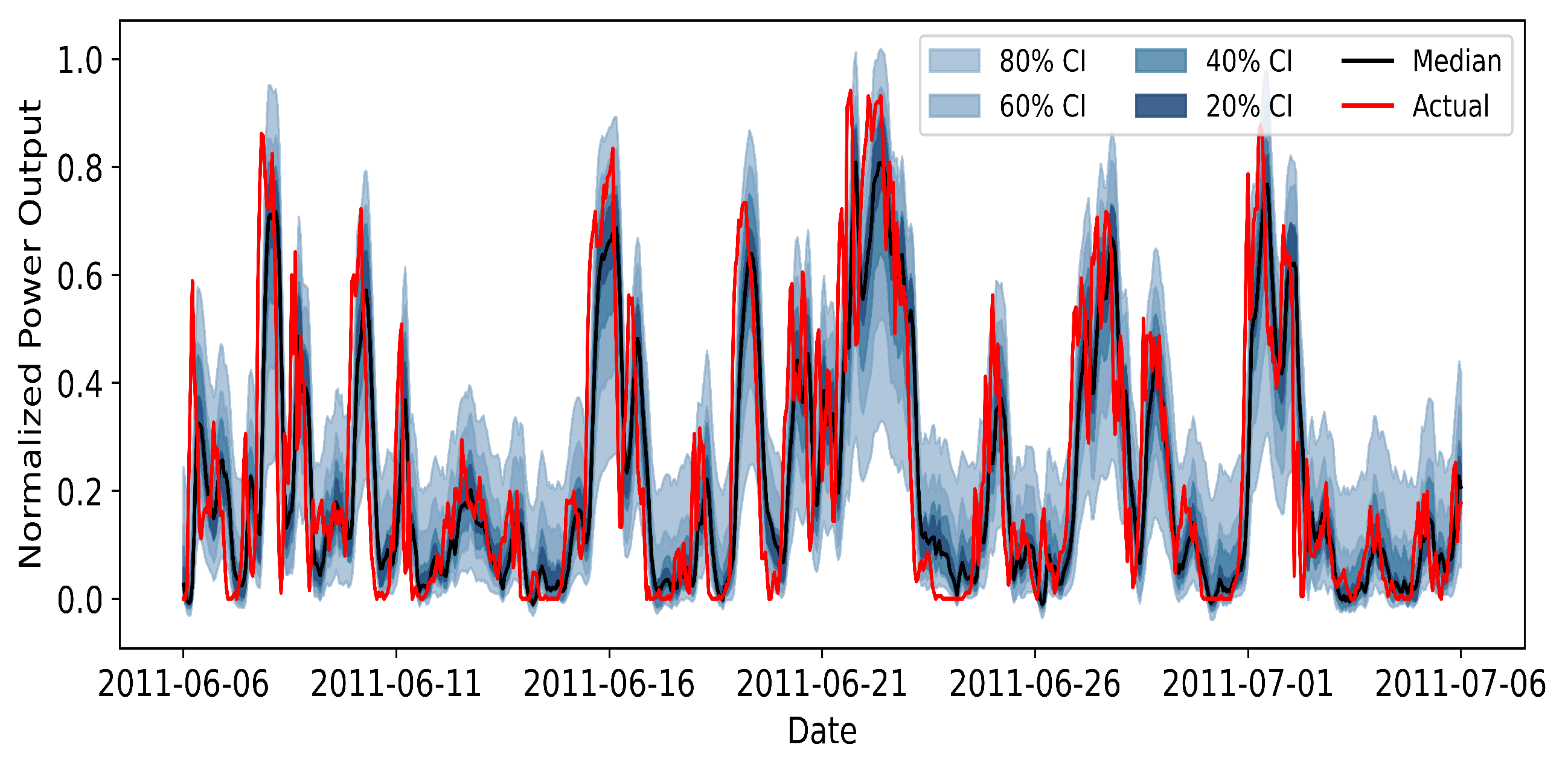

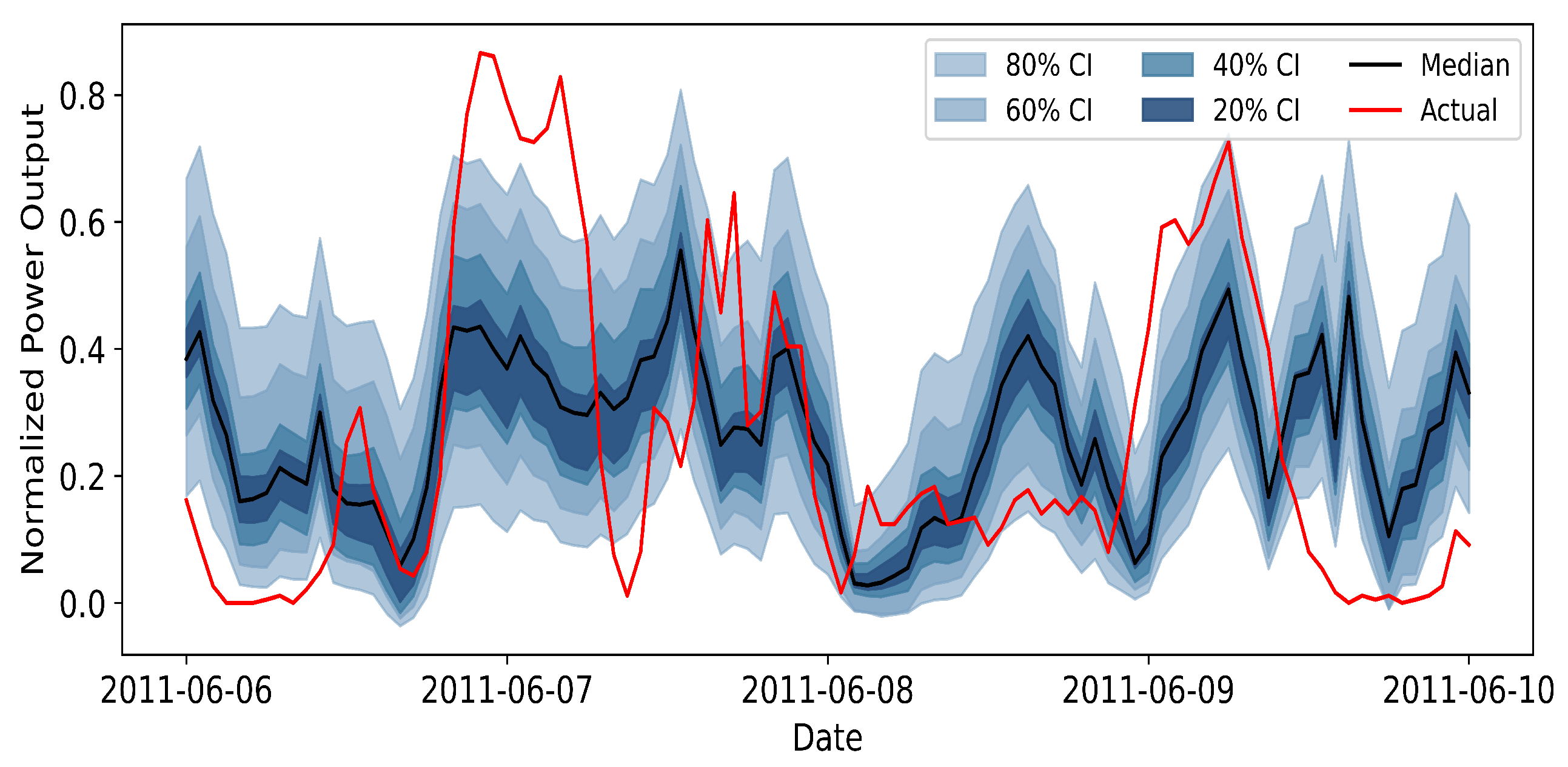

To generate probabilistic wind power forecasts in a privacy-preserving manner, we adopt an adaptive federated learning framework that couples a local quantile regression model with two mechanisms designed for Non-IID data and knowledge retention. At each communication round, every wind farm trains a local artificial neural network (ANN) with quantile regression loss on its own data and sends model updates to a server or cluster center without sharing raw measurements. The server aggregates these updates within clusters of clients that exhibit similar learning behaviour, as determined by an Adaptive Clustering (AC) strategy, and maintains a separate global model for each cluster. After global aggregation, each client performs a personalized fine-tuning step regularized by Elastic Weight Consolidation (EWC), which discourages large deviations of parameters that are important for the cluster-level model. This combination of FL, AC, and EWC yields cluster-specific global models and personalized local models that jointly provide calibrated probabilistic forecasts while respecting data locality.

Probabilistic WPF methods are broadly categorized into two main approaches, i.e., parametric and non-parametric. Parametric methods assume that the wind power error follows a predefined probability distribution and then predict the parameters of that distribution. Non-parametric methods learn the uncertainty directly from data without assuming a specific distribution form, such as Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) and Quantile Regression (QR). Within deep learning models, Quantile Regression is widely adopted due to its directness, flexibility, and minimal assumptions regarding the data distribution.

In Quantile Regression, the model is trained by minimizing the Pinball Loss (also known as Quantile Loss or Check Loss). This minimization ensures that the predicted quantile

precisely splits the actual value

into proportions

and

. The definition of the Pinball Loss

clearly demonstrates the asymmetric penalty mechanism for overestimation and underestimation:

Here,

is the target quantile, typically ranging from

to cover various confidence levels required for the prediction interval. When the prediction

is less than the actual value

, the loss is weighted by

; conversely, it is weighted by

. This asymmetric penalty ensures that the model learns the

value that is indeed the

-th quantile point of the data distribution. The overall training objective is to minimize the average loss across all quantiles, defined as the local loss

. For a dataset with

m quantiles and

samples, the total average loss

is:

This comprehensive loss function guides the neural network training to output predictions that simultaneously satisfy the requirements of multiple quantiles.

To address the Non-IID nature of local datasets across wind farms, we introduce an adaptive clustering procedure that groups clients with similar preference scores and jointly trains a cluster-specific global model. Within each cluster, model parameters are aggregated in a federated manner to capture shared patterns among the corresponding wind farms. Furthermore, elastic weight consolidation (EWC) is employed during local personalization to preserve important global knowledge: parameters that are estimated to be critical for the global model are penalized if they deviate too much from their global values, which mitigates catastrophic forgetting while still allowing client-specific adaptation.

The purpose of the AC strategy is to automatically identify and separate clients with similar model learning characteristics and data distributions without exposing raw data. These clients are assigned to distinct clusters , and a customized global model is trained for each cluster. The detailed steps are as follows.

Warm-up Training: The server initializes k models and distributes them to all clients. Each client trains these k models locally for a small number of epochs (e.g., rounds) using the local loss . This stage is designed to help clients move past initialization randomness and establish stable, distinguishable preferences for the k models.

Preference Score Update: During the clustering phase, clients no longer update all

k models. Instead, they use the performance

(Pinball Loss) of the

k models on their local validation set to update the preference score

. The model yielding the best performance is deemed the client’s favorite. The decay rate

controls the influence of historical preferences.

Intra-Cluster Aggregation: The server receives the parameters of the client’s favorite model. Based on the model index , the client is assigned to the corresponding cluster . Aggregation is performed only within the cluster to prevent gradient conflicts arising from severe data heterogeneity between different clusters. The clustering process terminates when the client preferences remain unchanged for consecutive epochs, ensuring stability of the clustering result.

Elastic Weight Consolidation (EWC) first identifies which global parameters

are critical to the overall global model performance. It uses a diagonal approximation of the Fisher Information Matrix to calculate the importance

for each model parameter

. This value is based on the average of the squared first-order derivatives (gradients) of the local loss function

with respect to the parameter on the local dataset

:

A higher

value indicates that the parameter is more critical for the model’s core feature extraction capabilities, and thus should be more strictly protected during fine-tuning. EWC Loss Function: During personalized fine-tuning, the EWC Loss function

is used. It supplements the original local loss

with a regularization term. This term penalizes the parameter

for deviating too far from the initial global model parameter

, scaled by its importance

:

The term is the consolidation weight, which balances local adaptation against global knowledge preservation. By minimizing , the model adapts to local data while retaining critical global knowledge, leading to robust personalization.

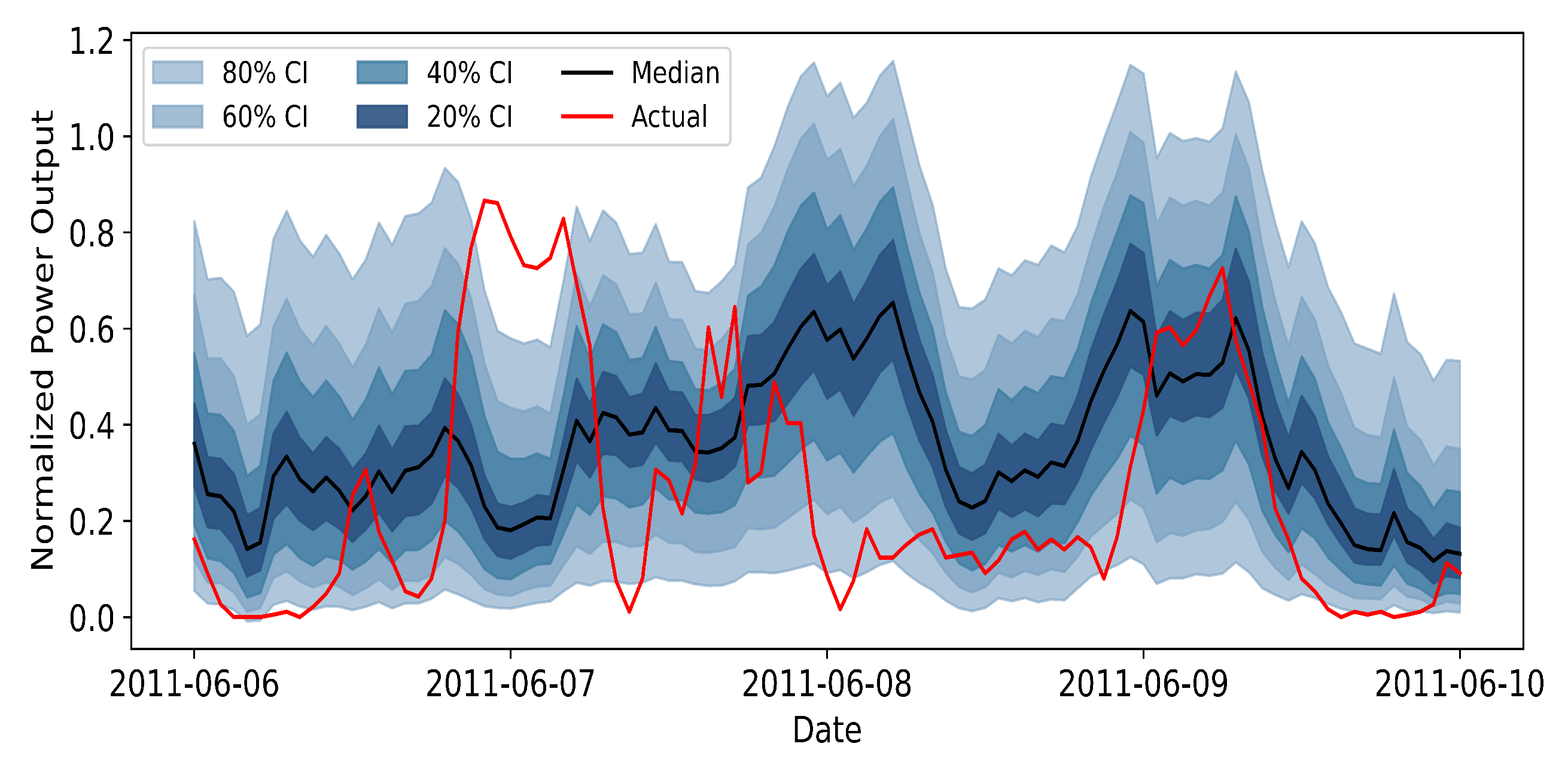

When using larger local learning rates or increasing the number of fine-tuning epochs, the performance of the FL + AC + EWC model remains stable and the power system obtain the prediction wind power .

Furthermore, to objectively verify the rationality of the AC-based grouping of wind farms, we further evaluate the resulting clusters using two standard internal cluster validity indices, namely the silhouette coefficient and the Davies–Bouldin index. The silhouette coefficient ranges from

to 1 and measures how similar a client is to its own cluster compared with other clusters, with larger values indicating more compact and better-separated clusters. The Davies–Bouldin index, in contrast, quantifies the average similarity between each cluster and its most similar counterpart, where smaller values are preferred. Using the GEFCom 2014 wind farm data, we compute these indices for the clusters produced by the AC procedure, and the results are summarized in

Table 1. The positive silhouette coefficients and Davies–Bouldin indices well below

indicate that the wind farms assigned to the same cluster indeed share similar data distributions and learning characteristics, which confirms the rationality of the learned grouping.

Let

denote the predicted

-quantile of the aggregated wind power at time

t, while the uncertainty of the forecast is summarized by a one-sided prediction interval

which can be interpreted as a wind-related reserve requirement to hedge against underproduction relative to the median. The net power deviation that must be compensated by controllable loads is then modelled as

where

is the nominal (day-ahead) schedule. In this way, both the level (via

) and the uncertainty (via

) of the probabilistic forecast directly determine the right-hand side of the load-side balance constraint in the ADMM-based dispatch problem.

The probabilistic forecasts produced by the adaptive FL model serve as inputs to the subsequent ADMM-based load-side dispatch and anomaly detection module. Specifically, for each forecasting horizon step, the FL framework outputs a set of quantile predictions for the aggregated wind power, which can be summarized by a representative value (e.g., the median) and an associated prediction interval. In the dispatch formulation, the representative forecast is used as the scheduled wind generation level, while the width of the prediction interval determines a reserve margin that is allocated on the load side to hedge against forecast errors. In this way, the quality and calibration of the probabilistic forecasts directly influence the amount of corrective action required in real time: more accurate and better calibrated forecasts lead to smaller imbalances and fewer adjustments, whereas biased or overly dispersed forecasts result in increased reserve deployment and more frequent anomaly signals in the distributed optimization layer.

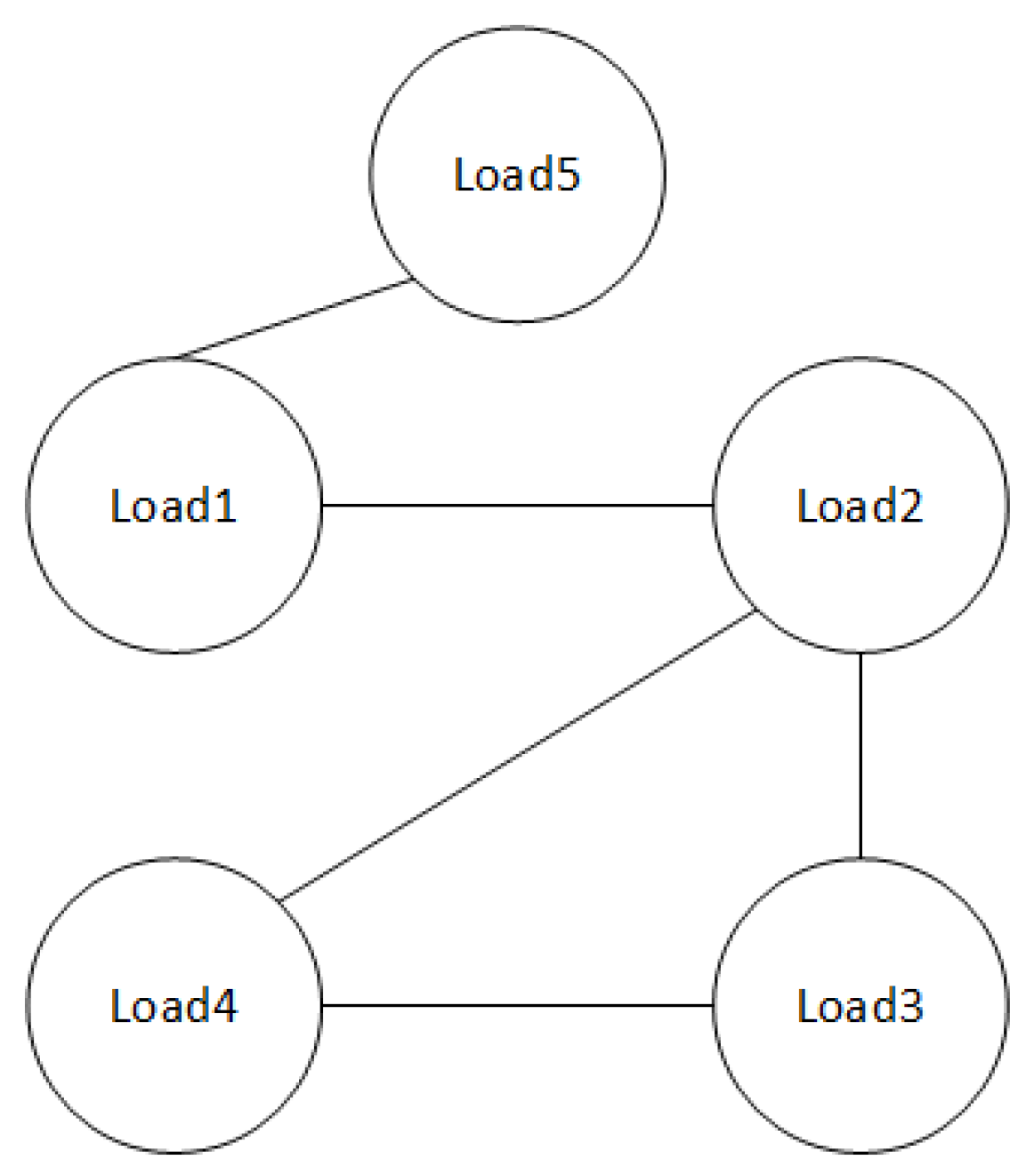

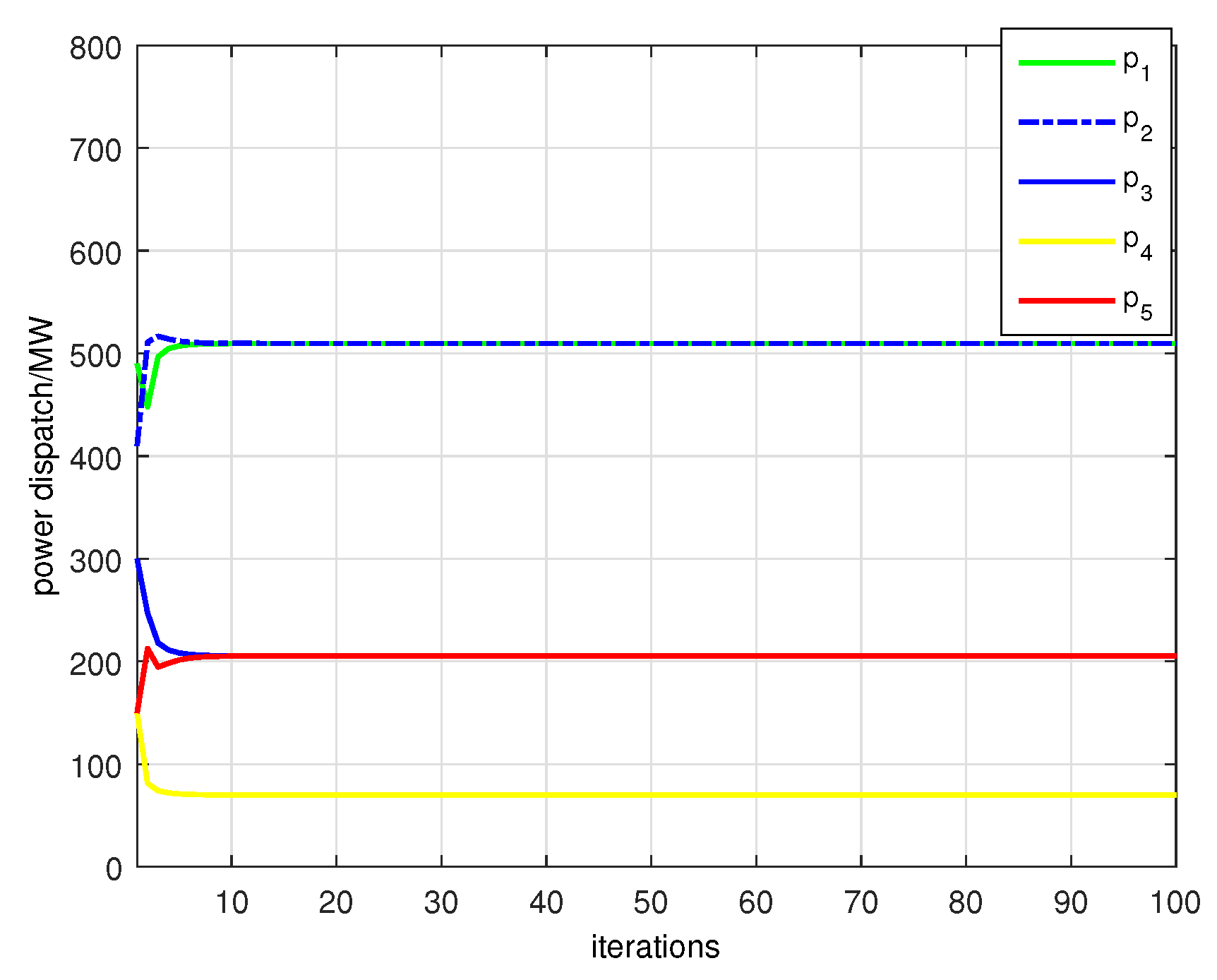

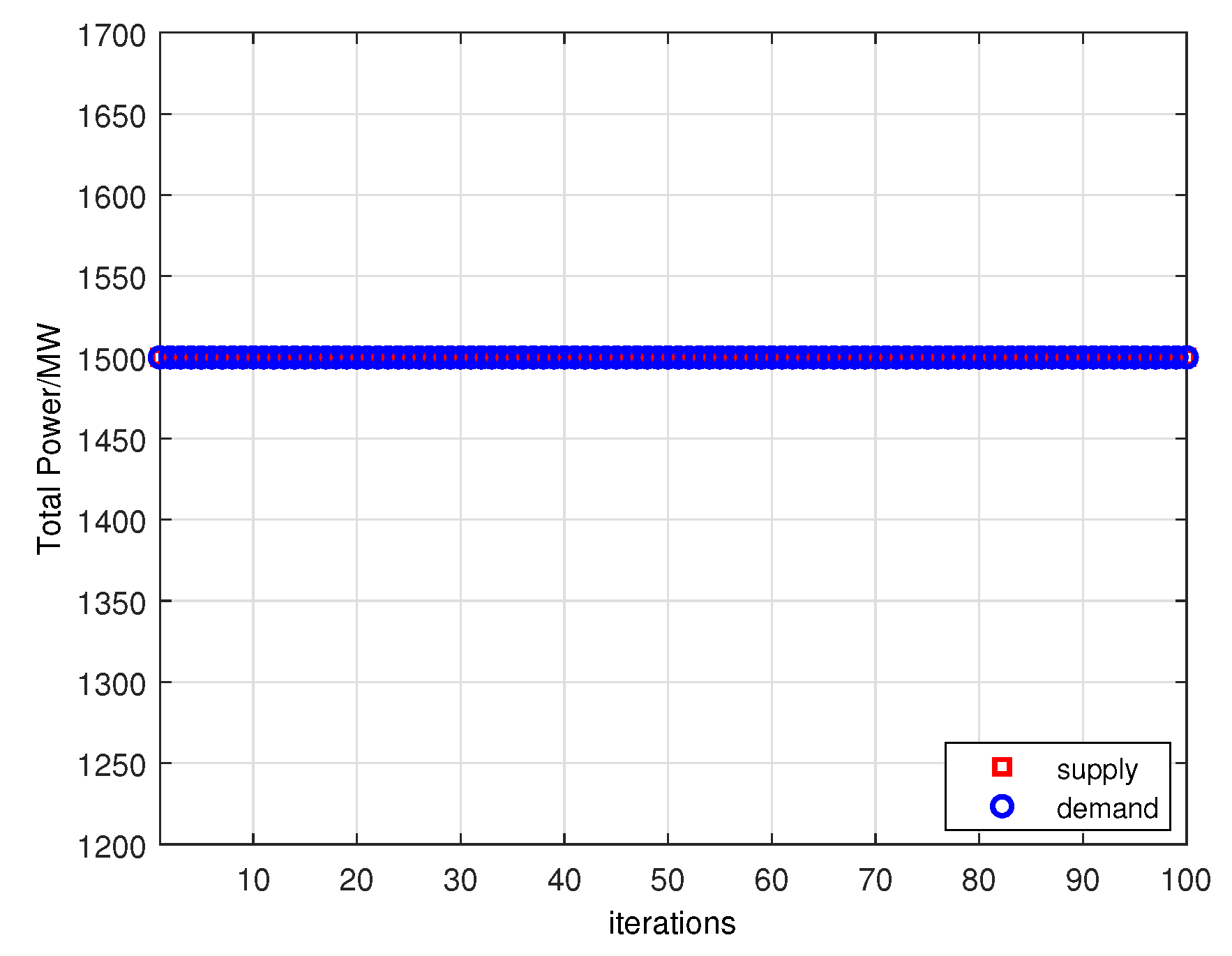

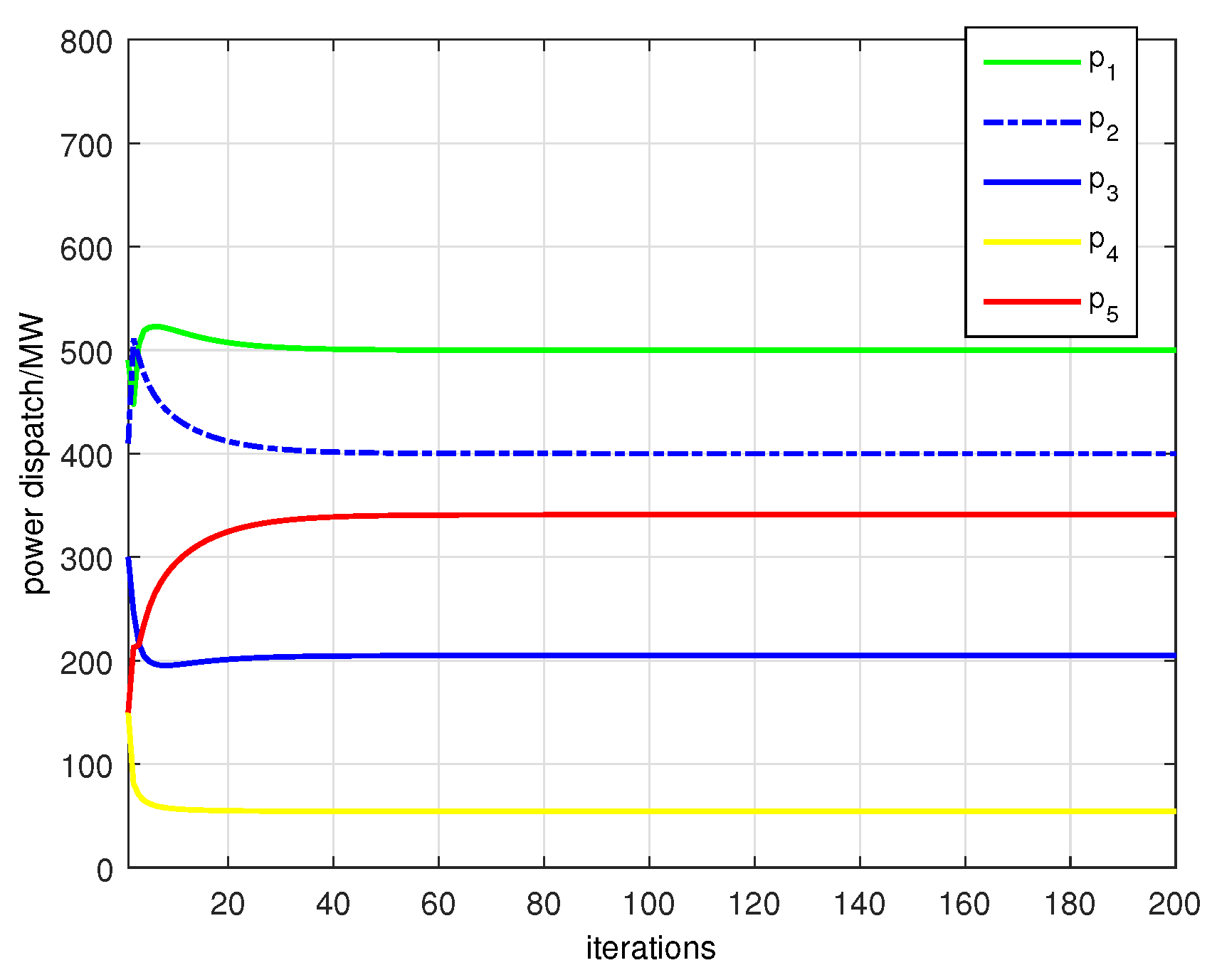

3.2. ADMM-Based Load-Side Distributed Management Algorithm

In this article, each participant in the power system is simulated as an agent for operation. It is assumed that at time

t, there is a power drop at the generation side of the power system, and this event can be detected quickly. Correspondingly, a single load

i on the load side will also decrease by a power value of

, and this value is constrained by the nature of the load itself, that is

In the formula, represents the maximum power variation of load i. The decrease in power of each load can lead to economic issues, making it a point worth considering for both users and grid companies on how to minimize the overall loss of such sudden events.

The purpose of the load scheduling problem in this article is to plan the power consumption of each load agent so that the entire power grid system can operate normally in the most efficient state, minimizing the overall loss during this failure. Therefore, the scheduling management problem of the smart grid with wind power can be expressed in the following form:

In the formula, represents the negative benefit of load i, and the parameter variable . .

In the unconstrained case, the load-side dispatch problem only enforces the global power-balance equality

, and the ADMM iterates are effectively free to assign any adjustment

to each bus as long as the total change matches the wind power deviation

. This corresponds to an idealized scenario in which all controllable loads can, in principle, increase or decrease their consumption without individual limits. In practice, however, each industrial load has physical and operational bounds, i.e., the power adjustment

cannot exceed the available flexibility at bus

i, and it must remain within a safe operating range. We capture these limits by imposing box constraints

where

represents the minimum admissible adjustment (e.g., to avoid shutting down critical equipment or violating comfort constraints) and

represents the maximum admissible adjustment (e.g., due to device ratings, process requirements, or contractual limits). Mathematically, these bounds appear as inequality constraints in the ADMM subproblems and are implemented via projections onto the interval

in the

p-update. When the constraints are inactive, the ADMM updates coincide with those of the unconstrained case; when some loads hit their bounds, subsequent iterations must redistribute the remaining imbalance to the still-flexible loads, which affects the shape and speed of convergence.

In order to use the ADMM algorithm in

Section 2, we need to make some changes to the formulation of the problem. Define two convex sets

and

:

Next, we will introduce two functions

and

to represent the indicator functions of the sets

and

, respectively:

Therefore, the economic dispatch problem (

23) can be directly transformed into the following form:

Then, the Lagrangian augmented function for problem (

26) can be written as:

By applying the ADMM algorithm, a centralized solution to problem (

26) can be obtained:

Since the information for each load needs to be centrally calculated for scheduling and allocation, the iterations from equations in (

28) are centralized. However, in practical applications, centralized methods have many limitations. The entire system requires a centralized controller that connects all loads to calculate scheduling problems with wind power system model. Once this controller is attacked or damaged, the scheduling problems cannot be resolved adequately, leading to all loads not operating under normal conditions, which directly results in significant losses. Additionally, due to the presence of the centralized controller, the entire load topology is known and fixed in advance. Therefore, when a sudden event causes a load to disconnect, the overall system topology changes, and the controller cannot obtain global load information, preventing optimal scheduling of the overall system.

Using Equations (26) and (27), convert problem (

23) into the following equivalent form:

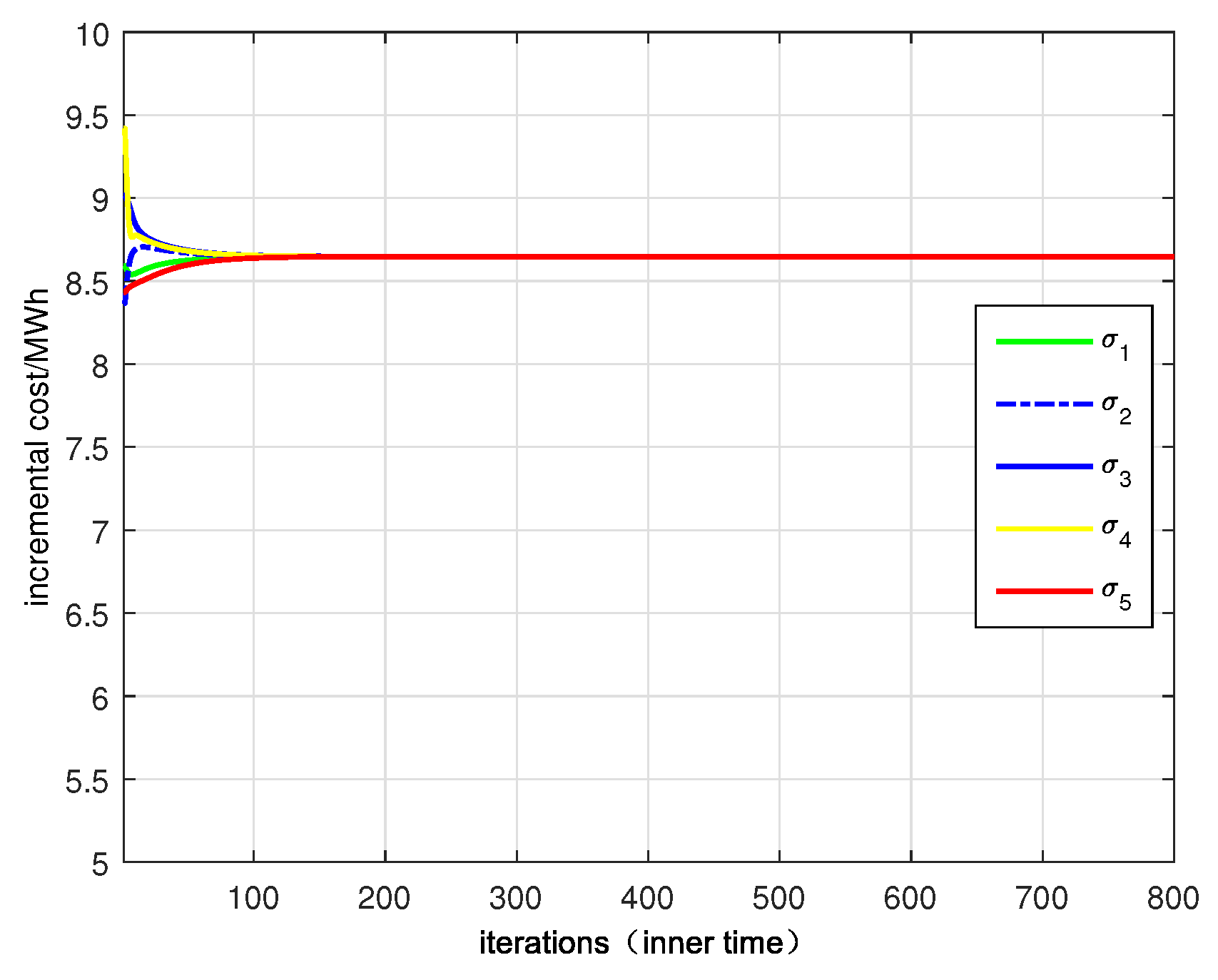

Therefore, the gradient value of

can be expressed as:

The cost of the controllable rotating device can be simulated as the following quadratic function:

In the equation,

and

are the cost function coefficients related to load

i, and

is the power consumption of load

i. Similarly, by setting

and

, we can transform Equation (

31) into another form:

There are also some positive and negative properties of the coefficients:

and

. The cost function

i (

31) and (

32) are equivalent, and here the latter is used to simplify the subsequent analysis. Due to the similar structure of the supply-demand balance equality constraint in (

23) and the controllable intelligent load and rotating equipment, the cost function of this type of load is often modeled in the same form as (

31) and (

32). Therefore, the negative benefits of the demand-side load can be obtained:

In the equation,

and

have exactly the same properties as the aforementioned

and

. Combining Equation (

31) and the above equation, we can obtain:

Since the power system network contains thousands of loads that belong to different users, using a distributed form inevitably involves exchanging information between neighboring users. Based on this consensus algorithm, the economic scheduling problem under supply and demand balance constraints can be quickly solved.