1. Introduction

Population modelling sits at the crossroads of demography, applied mathematics, and computational science, offering vital tools for understanding societal change. Classical methods—from stable population theory to matrix-based models—have provided important insights into growth, decline, and long-term dynamics, yet they often struggle to balance detailed demographic variation with the need for large-scale, policy-relevant predictions. This tension motivates the current work, which broadens traditional frameworks by connecting micro-level demographic processes with macro-level population trajectories through a clear, scenario-aware forecasting design.

Precise and clear population forecasts are vital for public policy, infrastructure planning, and resource allocation. The cohort-component method (CCM) [

1] is the main approach in official projections, analysing population change by age- and sex-specific fertility, mortality, and migration. While appreciated for its simplicity, CCM’s reliance on trend continuation reduces its effectiveness during demographic shocks like pandemics, forced migration, and financial crises. These challenges emphasise the need for forecasting frameworks that remain reliable in volatile environments and operate effectively with limited data.

This study addresses the following question: Can population forecasts in crisis-prone or data-limited settings be made more robust by integrating scenario-sensitive signals into a machine-learning (ML) ensemble that models demographic rates while suppressing spurious fluctuations? Our aim is to produce forecasts in which deviations from the baseline stem solely from explicit, well-defined scenarios, thereby enhancing interpretability and credibility.

To this end, we suggest a regression-ensemble framework that combines robust Huber regression with a correction mechanism based on the slope of an Exponential Moving Average (EMA) of historical rates. The ensemble retains lasting demographic signals, prevents overfitting to short-term noise, and incorporates explicit scenario flags to trigger genuine shocks. This design improves the CCM with data-driven modelling while keeping transparency.

It formalises a scenario-conditioned regression ensemble combining Huber regression with an EMA-slope anchor to stabilise trajectories.

It specifies a transparent mapping from scenario switches to fertility, mortality, and migration models, which are then propagated through age-structured CCM projections.

It defines a minimal, reproducible validation protocol for short official series using rolling one-year-ahead evaluation and decorrelation-guided lag limits.

It documents how scenario responsiveness depends on historical signal strength, clarifying when shocks generate observable divergence from baseline.

Two broad classes of population forecasting approaches contextualise our contribution: deterministic CCMs and statistical/ML methods. CCM remains foundational in national projections [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], with demographic transitions modelled via fertility, mortality, and migration [

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, their dependence on extrapolation makes them vulnerable to unexpected shocks [

17,

18,

19].

Statistical models such as ARIMA, exponential smoothing, and transfer-function models [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] provide data-driven alternatives. The Lee–Carter model [

26,

27] and Bayesian extensions [

28,

29] underpin modern probabilistic forecasts, while multilevel models address data scarcity [

30,

31,

32]. Model averaging further improves robustness, especially for migration and fertility [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

Machine-learning methods are increasingly used in demographic forecasting [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50], with techniques including LSTM, random forests, XGBoost [

51,

52], and regularised regressions [

53,

54,

55]. Yet, these models often lack interpretability, struggle under sparse data, and neglect scenario-based reasoning [

14,

30]; they have historically been used to demonstrate how flexible function approximators can capture complex demographic patterns when long, high-frequency, or granular datasets are available. Ensemble learning [

56,

57,

58] and symbolic discovery such as SINDy [

59], though promising, face difficulties with noise [

60,

61]. Geospatial and census-integrated models [

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69] and spatial Bayesian hierarchies [

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76] further highlight the need for robust, interpretable methods in sparse contexts.

A central methodological gap concerns the treatment of shocks. Demographic components—especially migration—are highly shock-sensitive [

37], yet many models implicitly assume temporal continuity, leading to poor prediction of inflexion points [

45]. Empirical evidence shows distinctive crisis responses: short-term fertility rebounds after pandemics [

77], increased health expenditure during public health emergencies [

78], rising unemployment in financial shocks [

79], and altered fertility among refugees [

80]. In our framework, such stylised effects enter through scenario flags rather than being mistaken for noise.

We therefore extend the CCM by embedding scenario-sensitive flags within a regression ensemble that uses Huber regression [

81,

82] to down-weight outliers and an EMA-slope anchor [

25,

83] to preserve long-run signals. A smoothing safeguard prevents implausible year-on-year jumps. This reframes population forecasts as conditional statements tied to explicit assumptions, rather than unqualified projections of past trends.

The approach is designed for sparse data environments: lagged dynamics, socioeconomic indicators, and scenario switches capture available structure without overfitting. Validation uses data from Germany, Norway, and Portugal (2001–2024), generating forecasts to 2040 under baseline and crisis scenarios. One-year-ahead out-of-fold scoring evaluates both overall and age-specific accuracy. Scenario design remains grounded in empirical evidence to avoid unrealistic deviations.

Conceptually, the framework elevates scenario reasoning from a qualitative planning exercise to a formal element of statistical population modelling, linking narrative foresight to quantitative projection. While limited by short historical series and by the simplicity required for interpretability, the method offers a transparent and reproducible basis for exploring demographic futures under both stability and disruption.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows.

Section 2 describes the data and preprocessing;

Section 3 details the modelling framework, regression ensemble, scenario flags, and stability analysis;

Section 4 presents results for Germany, Norway, and Portugal including baseline and crisis forecasts to 2040; and

Section 5 discusses limitations, policy implications, and directions for future research.

2. Data

Our analysis relies on demographic and socioeconomic data from Germany, Portugal, and Norway, collected from official national statistical agencies [

6,

8,

10]. The core of the dataset includes age-specific fertility rates (ASFRs), mortality rates, and emigration rates, with immigration recorded as absolute figures to reflect each national system’s reporting conventions. Each variable is consistently broken down by age group and sex, providing a structured set of cohort-level transition components. This structure ensures comparability across countries and aligns the dataset with the cohort-component framework that underpins most demographic forecasting models.

The selection of Germany, Portugal, and Norway reflects both data availability and the chance to test the framework under contrasting conditions. These countries provide consistently curated series with enough depth to support robust model evaluation, while differing in demographic and institutional settings. Germany represents a large continental population with significant migration inflows and periodic census revisions. Portugal exemplifies a medium-sized European nation with strong emigration patterns and a more recent record of digitisation. Norway offers a smaller but data-rich population, where migration closely relates to economic cycles and policy. This variation enables the assessment of the framework’s performance across diverse contexts, thereby increasing the relevance of the results beyond any single case.

The choice of three countries is based on the fact that they offer harmonised annual demographic and socioeconomic series with relatively few structural breaks. Broader international datasets, such as those from the United Nations or the World Bank, indeed provide longer historical coverage; however, they often include definitional shifts, aggregation changes, or interpolated intervals that complicate the estimation of short-horizon annual models. The present study, therefore, focuses on demonstrating the mechanism of the hybrid ensemble under controlled, internally consistent conditions. We acknowledge that extending the approach to a broader set of countries is a valuable next step and would help assess its generalisability under more heterogeneous data environments.

To complement the demographic series, we include socioeconomic indicators that provide additional context for population change. Specifically, GDP per capita, unemployment rates, and health expenditure as a percentage of GDP are incorporated, with data sourced from the World Bank [

84]. These indicators are not considered direct causal factors but rather auxiliary covariates that enable the regression ensemble to adjust forecasts in response to broader economic conditions. This approach ensures that the data environment reflects both the internal momentum of demographic rates and the external pressures that influence them.

The analysis covers roughly the last twenty years of available data. For Germany and Norway, continuous data series date back to the early 2000s, while for Portugal, reliable migration data begin in 2008. This time frame is selected based on data availability and statistical considerations. Despite Europe’s long history of demographic record-keeping, digitised and harmonised series are limited before the 1990s, particularly for migration and socioeconomic indicators. Additionally, older population data are highly autocorrelated, offering little extra predictive value once recent demographic trends are taken into account. Focusing on the past 20 years thus balances the capture of relevant changes and ensures comparability across countries.

Although official data sources form the basis of the dataset, they are not without limitations. Migration statistics remain vulnerable to under-reporting and definitional changes, and mortality and fertility series can also be affected by reclassification or methodological revisions. In the absence of external benchmarks, we assume that official figures are internally consistent and representative for modelling purposes. This approach provides advantages in terms of comparability and alignment with international standards, but it also introduces potential discontinuities, especially around census revisions. From a modelling perspective, this makes it essential to adopt methods that can accommodate sudden adjustments without mistaking them for genuine demographic shocks.

To assess internal consistency, we calculated the residual between the reported total population and the value implied by demographic accounting:

where

denotes the reported population estimate,

inflows (births and the previous population

),

reported deaths, and

net migration in the year

t. Applying this diagnostic across all three countries showed that Norway and Portugal exhibit only minor deviations consistent with routine adjustments, whereas Germany shows clear negative spikes in 2011 and 2022, both census years. These patterns indicate substantial revisions following enumeration and illustrate how population totals can diverge from component-based accounting even in well-developed statistical systems. For modelling, such corrections highlight the need to prevent short-term discontinuities from influencing long-term forecasts, while still allowing explicit scenario shocks to enter transparently (see

Figure 1).

We also assessed the statistical redundancy in the demographic rate series to inform lag selection for the regression ensemble. The decorrelation time is defined as the lag at which the absolute value of the autocorrelation function (ACF) drops below

, indicating that observations beyond this point provide little additional predictive information. Based on this diagnosis, the maximum lag was set at five years to strike a balance between capturing useful information and the limited length of the datasets. This complements the decision to restrict the analysis to approximately the past two decades, as extending further back would offer minimal useful signal and could introduce measurement inconsistencies.

Table 1 displays the estimated decorrelation steps for each country, illustrating that the five-year cap maintains the primary predictive content within the selected timeframe.

To summarise the structure of the dataset,

Table 2 lists all series by category. Population counts serve as the projection target, while demographic components provide fertility, mortality, and migration rates at the cohort level, and socioeconomic indicators supply auxiliary context. Together, these categories define the inputs used throughout the study. While the design adheres to established practices in demographic forecasting, the inclusion of socioeconomic covariates ensures that the dataset reflects both demographic trends and the broader economic context in which they occur. This summary concludes the description of inputs and prepares the ground for the methodological framework presented in the following section.

3. Methods

Our forecasting framework is founded on the cohort-component methodology (CCM), the standard demographic tool for projecting populations by age and sex. We expand this traditional structure by incorporating a regression ensemble for rate forecasting, socioeconomic covariates, and event indicators, and implementing smoothing procedures for volatility. Together, these elements form an integrated population projection system that advances cohorts year by year while remaining flexible enough to accommodate external shocks.

3.1. Cohort-Component Projection Core

The population is disaggregated by age group

a and sex

. Let

denote the population of age

a, sex

s, in the year

t. Cohorts evolve according to the update:

where

is the mortality rate,

the emigration rate, and

the number of immigrants into that group.

New births replenish the youngest cohorts based on sex-specific age-specific fertility rates (ASFRs):

where

and

are fertility rates producing female and male births, respectively, from mothers aged

a. Fertility rates are computed relative to mid-year exposures, following demographic convention [

85].

This core provides the structural backbone of the projection, ensuring demographic consistency. The innovation of our framework lies in how the rates , , , and are themselves forecast.

3.2. Incorporation of Exogenous Factors

To move beyond purely autoregressive dynamics, we allow for external shocks. Our approach follows the logic of time-series models with exogenous regressors—such as ARIMAX and transfer functions [

21,

22]—and parallels modern machine learning approaches to time-series forecasting [

43,

47,

86].

We define a vector of binary event indicators

where

marks the presence of event type

k in the year

t. Examples include:

We interpret these flags as scenario levers rather than passive covariates. For instance, immigration among 25-year-old males in Germany exhibits sharp peaks in 2015 and 2022 (

Figure 2) [

87,

88], illustrating how refugee crises manifest demographically and motivating the explicit representation of such events.

Three classes of events are considered:

Pandemic: Disruptions to fertility, mortality, and migration during 2020–2021 [

89].

Refugee crisis: The Syrian influx of 2015–2016 and Ukraine-related displacement from 2022 onward [

87,

88].

Economic crisis: The 2008 global financial crisis and subsequent Eurozone downturn, particularly salient in Portugal [

90,

91].

By manipulating these flags into the future, we can construct counterfactual scenarios—such as recurring pandemics or prolonged recessions—and explore their demographic consequences.

The binary event vector

may be generalised to an intensity vector

with

, and a duration or memory term may be defined

which captures multi-year persistence. The same code accepts

and

, which directly encode severity and persistence. For the reported experiments, we set

and

for robustness with short series, but users can specify alternative

and

to simulate and estimate different intensities and durations.

Figure 2.

Immigration time series for 25-year-old males in Germany, highlighting spikes in 2015 (the Syrian war) and 2022 (the Ukrainian war).

Figure 2.

Immigration time series for 25-year-old males in Germany, highlighting spikes in 2015 (the Syrian war) and 2022 (the Ukrainian war).

3.3. EMA-Slope Anchor Under ARIMA-Type Dynamics

We anchor the short-run trajectory of demographic rates using the slope of an exponential moving average (EMA). For a time series

with a smoothing parameter

, the EMA is

We define the EMA-slope as the one-step change:

When

follows an ARIMA

process, the EMA-slope inherits stationarity from the differenced process. In particular, if

is ARIMA

with an autoregressive coefficient

, then

where

is the innovation variance. This illustrates that a smaller

dampens volatility but increases lag, while a larger

yields responsiveness but higher variance. Thus, the EMA-slope provides a tunable anchor balancing smoothness and adaptability under ARIMA-type dynamics.

If

is covariance-stationary with absolutely summable autocovariances, then the EMA

defined in (

6) is also stationary because it is a stable linear filter. The EMA slope

is a first difference of a stationary process, hence stationary as well. Under ARIMA

, differencing of order

d restores stationarity of the filtered series; see [

21,

83,

86]. Error propagation under the cohort recursion follows from a first-order expansion, detailed in

Appendix A.

3.4. Stability and Consistency of the Cohort-Component Recursion

The cohort-component recursion can be expressed in vector form as

where

is the age-by-sex population vector,

encodes survival and migration transitions, and

injects newborns.

Stability requires that the spectral radius of the expected transition operator satisfies

This ensures boundedness of long-run trajectories. Moreover, under ergodicity and bounded shock variance, forecasts are consistent in the sense that

where

denotes forecasts and

the realised populations. Thus, the recursion maintains internal demographic balance while asymptotically stabilising under regularity conditions.

3.5. Error Propagation Under Shock Regimes

Let

denote the forecasted rate (mortality, fertility, or migration) and

its truth. Define the rate error

. Because CCM recursion multiplies survival and fertility rates across successive ages, errors compound multiplicatively:

Linearising for small errors yields

Thus, the variance of forecast errors grows approximately linearly in h under independent shocks. However, clustering of shocks introduces temporal correlation, amplifying uncertainty through interaction terms. This motivates the explicit modelling of shock processes rather than treating them as white-noise disturbances.

3.6. Regression Ensemble for Demographic Rates

The regression ensemble forecasts the key inputs to the cohort-component equations. Two categories of targets are distinguished: (i) demographic rates—fertility, mortality, emigration, and immigration counts—modeled at the cohort level by age and sex, and (ii) socioeconomic indicators, modeled globally.

Let

denote a demographic rate and

a socioeconomic indicator. Then:

where

L is the maximum lag determined via decorrelation analysis.

The regression function

is defined as an ensemble of two components: a Huber regressor, robust to outliers, and an exponential moving average (EMA), which anchors long-term trends. The Huber component solves

with

the Huber loss. The EMA component extrapolates smoothed trends using a rolling regression on recent EMA values. The ensemble forecast is then

with

w determined by out-of-fold one-year-ahead RMSE. This weighting ensures that the ensemble adapts: leaning on the Huber regressor when covariates improve short-horizon accuracy, and on EMA when long-run momentum dominates.

Conceptually, EMA stabilises the trajectory, while the Huber component responds to short-term signals and shocks. Hyperparameters, including the Huber threshold

, are tuned using the same OOF validation. As an additional safeguard, forecasts that exhibit implausible volatility are smoothed using an exponentially weighted correction [

25,

86].

Unlike in standard applications, where EMA is used to smooth levels, here we use the EMA slope as a forecasting baseline. This provides a transparent and adaptive estimate of long-run momentum, ensuring that forecasts are anchored to a plausible trajectory even when short-run predictors are noisy or underperform. To our knowledge, applying the EMA slope in this role is novel in demographic forecasting.

Lagged predictors are included up to five years, based on the decorrelation analysis presented in the Data section. This yields parsimonious autoregressive structures consistent with the limited annual data available.

It should be noted that the ensemble weight w is based on OOF one-year-ahead RMSE to prioritise stability in short annual series. Longer-horizon validation would be desirable but cannot be supported reliably when the available history spans only a few decades. By basing the weight on short-run predictive skill, the ensemble avoids overfitting structural trends that are weakly identifiable in sparse data. Similarly, the fixed decorrelation lags are designed as pragmatic approximations that maintain numerical stability across components. We acknowledge that fertility, mortality, and migration exhibit distinct autocorrelation patterns, and that more flexible lag structures or Monte Carlo sensitivity analysis represent valuable methodological extensions. Incorporating such refinements is identified as an important avenue for future work, particularly when richer datasets become available.

Given data sparsity, cross-method numerical comparisons can be fragile and sensitive to specification choices and leakage. We therefore report internal performance via out-of-fold error and use the ensemble’s two components (EMA-only and Huber-only) as conceptual baselines.

Table 3 reports quantitative errors for key series; fuller head-to-head baselines are deferred to future work with longer histories.

3.7. Population Projection Algorithm

The full forecasting pipeline proceeds iteratively as follows:

Initialization: Start from the observed population by age and sex, , in the last available year .

Scenario design: Define event trajectories for the forecast horizon, encoding assumptions about exogenous shocks.

Rate model training: Estimate the regression ensembles for demographic rates and socioeconomic indicators using lagged histories, covariates, and event flags.

Rate forecasting: Produce annual forecasts for each rate, combining Huber and EMA components with RMSE-based weighting and volatility smoothing.

Population updating: Substitute forecasted rates into the cohort-component equations, advancing cohorts and generating new births.

Iteration: Repeat the process sequentially for each forecast year until the end of the horizon, yielding age-structured population trajectories under the specified scenarios.

This workflow ensures projections remain internally consistent with demographic accounting, responsive to socioeconomic and event-driven signals, and resilient to noise and volatility.

The purpose of the proposed framework is not to claim high-precision point forecasts at such horizons. Instead, the central outcome of the study is the development of a transparent, scenario-conditioned mechanism for stress-testing demographic futures under explicit assumptions.

The methodological contribution lies in showing that CCM-based demographic processes can be combined with robust regression components and scenario-sensitive flags to produce conditional trajectories that respond in controlled ways to shocks such as pandemics, refugee inflows, or economic downturns. The resulting forecasts should therefore be interpreted as conditional projections: they map each explicitly stated scenario to a corresponding demographic pathway. This differs fundamentally from attempts to produce single “best” long-term forecasts, which are known to be dominated by structural uncertainty arising from volatile components such as migration.

By highlighting the limits of long-term point accuracy, the paper follows established demographic practice and emphasises that uncertainty is an inherent property of medium- and long-run population dynamics. The contribution of the proposed framework is thus not to eliminate this uncertainty, but to make it explicit, structured, and reproducible. This allows researchers and policymakers to evaluate how alternative assumptions propagate through fertility, mortality, and migration pathways, and to compare the robustness of outcomes across scenarios. In this sense, the ultimate aim of the paper is clarity and transparency in demographic stress testing, rather than precise deterministic forecasts.

Having established the forecasting framework and its components, we now move to an empirical evaluation of its performance. The results (in the following section) show how the model performs across the three country contexts, assessing both the accuracy of short-term forecasts and the plausibility of long-term projections under various scenarios. In doing so, we emphasise the practical value of integrating socioeconomic covariates and event indicators into a cohort-component projection system.

4. Results

Given the limited availability of annual demographic time series from official sources, we employ a time-series regression ensemble to project future rates. The ensemble automatically selects lags of past values alongside global predictors, with recent lags strengthened to decrease sensitivity to shocks. A fallback smoothed-trend mechanism guarantees stable forecasts when the ensemble performs poorly. This method balances flexibility and simplicity, delivering reliable rate estimates from short historical records.

A natural question is whether demographic projections could be produced at a higher temporal resolution, such as monthly, in order to capture short-run volatility in migration, births, or deaths. However, two structural constraints make this infeasible. First, harmonised monthly demographic series do not exist for the countries examined, nor for most official statistical systems; where monthly releases are available, they are typically incomplete, non-harmonised, or subject to substantial revision.

Second, and more fundamentally, the decorrelation analysis shows that demographic rates lose statistically meaningful temporal dependence after approximately 20–25 years of annual data. This implies that lags beyond this horizon contain no predictive signal that can be exploited reliably by any forecasting model. In other words, the intrinsic memory of demographic processes is short. Even if monthly data were available, their high-frequency fluctuations would not correspond to additional predictive structure, but rather to noise that cannot be estimated or validated, given the identified decorrelation limits.

These structural properties also constrain the validation strategy. When the informative temporal window is limited by decorrelation rather than by data quantity, annual out-of-fold evaluation becomes the only statistically defensible approach: it preserves independence between training and validation intervals, while avoiding the overfitting that would arise from attempting to learn from non-informative or decorrelated lags. More complex validation schemes or artificially upsampled high-frequency series would violate these identifiability constraints and give a false impression of forecasting precision.

For these reasons, the proposed framework focuses on transparent, scenario-conditioned annual projections. The aim is not to model speculative month-to-month dynamics, but to provide a reproducible mechanism for assessing the impact of explicit crisis assumptions on demographic trajectories, within the limits set by the intrinsic temporal structure of demographic processes.

4.1. Model Fit and Predictive Accuracy

To evaluate model performance, the ensemble is trained on historical data between 2001 and 2024 and validated using a one-year-ahead out-of-fold (OOF) approach. This simulates the real forecasting process, thus providing a realistic assessment of predictive accuracy. Then, the model is used to make predictions under different scenarios through 2040. The forecast horizon up to 2040 is constrained by the decorrelation analysis, which indicates that temporal correlations in the data effectively vanish beyond approximately 20–25 years.

Table 3 reports the mean normalised RMSE (nRMSE) for the Huber regression component, which anchors the short-horizon forecast. The exponential moving average (EMA) slope component is not optimised for OOF accuracy but instead provides long-term trend stability. Across countries, fertility rates (ASFR) show comparatively low errors (0.12–0.17), followed by unemployment (0.03–0.05). Mortality rates and health expenditure fall within an intermediate range (0.15–0.21). Migration-related series exhibit higher error levels, with immigration reaching 0.34 and emigration reaching 0.32. GDP per capita is moderately accurate for Germany and Norway, but substantially noisier in Portugal (0.45).

Lag selection typically includes three to five annual lags, with five as the maximum, due to the limited length of official demographic series (15–20 observations per cohort). This provides sufficient temporal depth without leading to overfitting. Emphasising the most recent lags further stabilises forecasts during shocks, while the fallback trend mechanism ensures sensible continuation if the ensemble fails. Overall, these design features improve both reliability and interpretability.

For Norway, health expenditure data were excluded because the available series is outdated and not comparable with Germany and Portugal. When included, its predictive accuracy falls within the same error range as fertility and unemployment.

4.2. Scenario Design

To examine the ensemble’s behaviour under different future scenarios, we establish a series of stylised “what-if” cases using binary event flags. Each scenario introduces a hypothetical shock between 2028 and 2030, targeting one event type at a time. This allows for structured counterfactual experiments that are uncommon in demographic forecasting, where structural shocks are often omitted or only modelled retrospectively.

While the event flags are explicitly included as exogenous predictors in the regression ensembles, their role is similar to that of intervention variables in ARIMA-type models: they influence rate forecasts only when historical data provides a clear signal to learn from. In practice, this means that activating a flag will not create large discontinuities in the series without prior evidence. Instead, the ensemble utilises past structural shocks (e.g., refugee surges in Germany) to interpret future flag activations as plausible deviations, while reverting to the baseline in smoother contexts where shocks have been infrequent or muted.

The modelled scenarios are:

Baseline: No crises after 2024; all event flags remain off. This represents a smooth continuation of recent trends.

Pandemic: A new pandemic emerges in 2028–2030, activating only the pandemic flag.

Refugee Crisis: A geopolitical conflict in 2028–2030 produces a surge in immigration, activated through the refugee crisis flag.

Financial Crisis: A sharp economic downturn in 2028–2030 is simulated by enabling only the economic crisis indicator.

Applied to the rate ensemble and propagated forward via the CCM population equation, these shocks affect fertility, mortality, and migration, as well as the global predictors, before resulting in population outcomes. They are not meant as forecasts, but as stress tests of plausible extremes. Unlike standard extrapolations, this approach enables policy-relevant stress testing of demographic futures, bridging quantitative forecasting with the more commonly used scenario-based reasoning in qualitative foresight. Note that scenario curves are close when historical signals linking crises to different shocks were weak or irregular, consistent with the ensemble’s conservative design.

4.3. Scenario Effects on Key Demographic Rates

The repository of all past data for the figures presented in this section is provided in the Data Availability Section; here, we focus on interpreting their implications for model behaviour and scenario responses. We begin with global predictors, starting with GDP per capita (

Figure 3).

Across all three countries, responses to the scenario are subdued. The autoregressive models capture general baseline trends but show little differentiation between scenarios, suggesting limited recurring patterns in GDP per capita for the ensemble to utilise. Germany’s historically volatile series stabilises after 2025, with only minor deviations under different crises. Norway stabilises quickly, with scenario trajectories essentially indistinguishable. Portugal, despite previous fluctuations, also converges closely to the baseline. In this case, scenario switches contribute little beyond trend continuation, and deviations are mostly superficial.

The limited responsiveness of GDP per capita to scenario flags underscores a vital distinction: when historical shocks do not leave lasting statistical marks, the model defaults to baseline trajectories. This aligns with the ensemble’s design but also implies that GDP dynamics need a broader set of predictors beyond autoregressive lags and binary event indicators. Specifically, adding sectoral or macroeconomic covariates (such as investment rates, trade balances, or fiscal shocks) could enhance scenario differentiation, whereas the current setup views GDP mainly as a smooth continuation process. The appearance of linearity should therefore be interpreted as a data-driven consequence of sparse annual observations rather than as an indication of insufficient model flexibility.

Unemployment (

Figure 4) shows a similar pattern. Since historical crises have not caused significant, visible spikes in unemployment, scenario levers have little effect. In Germany, the ensemble reflects the decline from double digits in the early 2000s to below three per cent today, continuing downward towards 1.5–2% by 2040. Norway remains steady around 3.5–3.7%. Portugal, in contrast, is expected to gradually rise back to 7–8% by 2040 after the steep decline post-2013. Once again, historical trends determine the strength of the projected scenario effects.

Health expenditure as a share of GDP offers more interpretable responses to scenario changes (

Figure 5). In Germany, spikes such as the 2020 surge are replicated when the pandemic indicator is activated, leading to a sustained increase above the baseline. Other shocks tend to stay closer to the trend. This alignment shows that the ensemble can translate external scenario switches into plausible deviations when there is historical precedent. Portugal’s projections are more subdued, as the financial crisis occurs near the start of its data, which limits broader applicability. Norway is excluded due to the absence of comparable data series.

Having considered global predictors, we now examine cohort-specific rates. While global variables inform these models, we do not interpret their individual coefficients, as doing so would require inspecting numerous specifications. Instead, we rely on Huber regression’s feature selection to robustly identify relevant predictors.

Male age-specific fertility rates (ASFRs) are shown in (

Figure 6). In Germany, scenario trajectories clearly diverge: refugee and pandemic crises push fertility above the baseline, while financial turmoil slightly lowers it. Norway exhibits flatter projections, as its historical pandemic-related fertility rise was too modest to register as a structural shock. Portugal shows the opposite: the model replicates the 2015 fertility rise in the refugee crisis scenario, while long-term trajectories revert to the trend.

Female ASFRs (

Figure 7) follow nearly identical dynamics, as expected given the joint nature of fertility outcomes. Both sexes respond similarly to the scenarios, confirming the model’s internal coherence.

Mortality among older female cohorts (

Figure 8) illustrates the same principle. In Germany, the downward trend persists with modest divergence across scenarios. Norway’s series is noisier, with little scope for significant deviations. Portugal’s mortality continues to decline steadily, with scenarios introducing only slight adjustments.

Immigration flows (

Figure 9) demonstrate how strongly the model responds to significant historical shocks. Germany’s 2015 spike is reflected in the refugee crisis scenario, resulting in a sustained upward shift. Norway’s notable peak is only partly activated, as it did not surpass global thresholds. Portugal shows no clear separation, indicating its smoother pattern history.

Emigration (

Figure 10) reinforces this pattern. Germany experiences both financial crisis surges and refugee-related spikes, with the pandemic scenario dampening mobility. Norway exhibits modest increases during crises, but trajectories remain close to baseline. Portugal exhibits flat paths, reflecting limited historical precedent.

4.4. Population Projections

Finally, we aggregate cohort-specific rates into population outcomes.

Figure 11 shows selected cohort projections. In Germany, shocks build up into lasting divergences: refugee crises raise levels through immigration, pandemics decrease emigration and also elevate trajectories, while financial crises lead to increased emigration and shift paths downward. Since these shocks influence flows, not just stocks, their impacts endure over time. Norway and Portugal, by contrast, exhibit subdued differentiation. Their scenarios largely mirror the baseline, reflecting the lack of significant past shocks in their series. Still, baseline demographic momentum remains well captured.

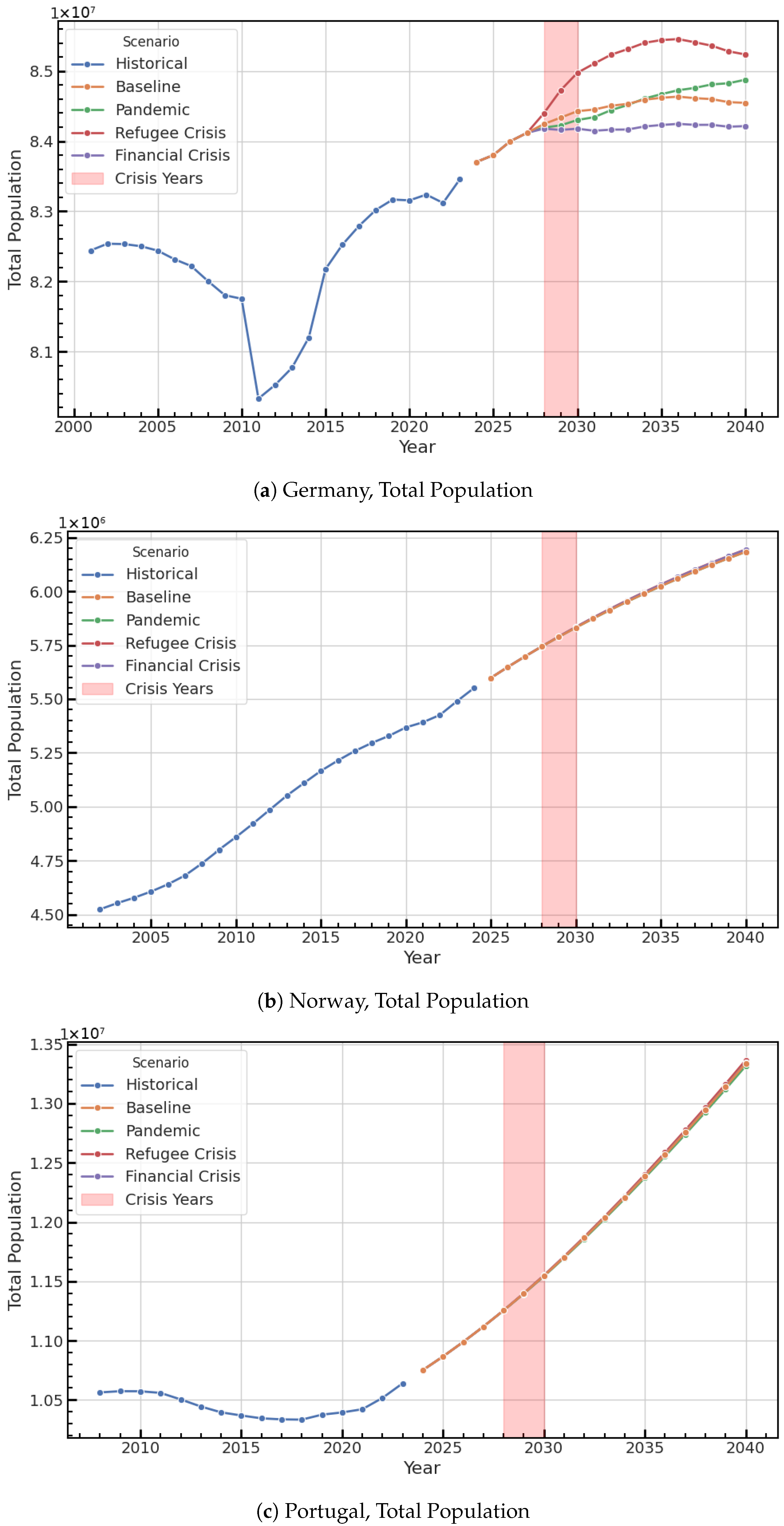

Total population outcomes are presented in

Figure 12. The logic remains similar: in Germany, scenarios diverge more sharply, especially during the refugee crisis, leading to a noticeable long-term increase. Norway exhibits modest differences, aligning with its stable demographic structure. Portugal stands out with a steep projected rise, likely due to its recent immigration, as reflected in the rate models. Here, baseline momentum primarily influences the outcomes, with scenario variation having only a secondary effect.

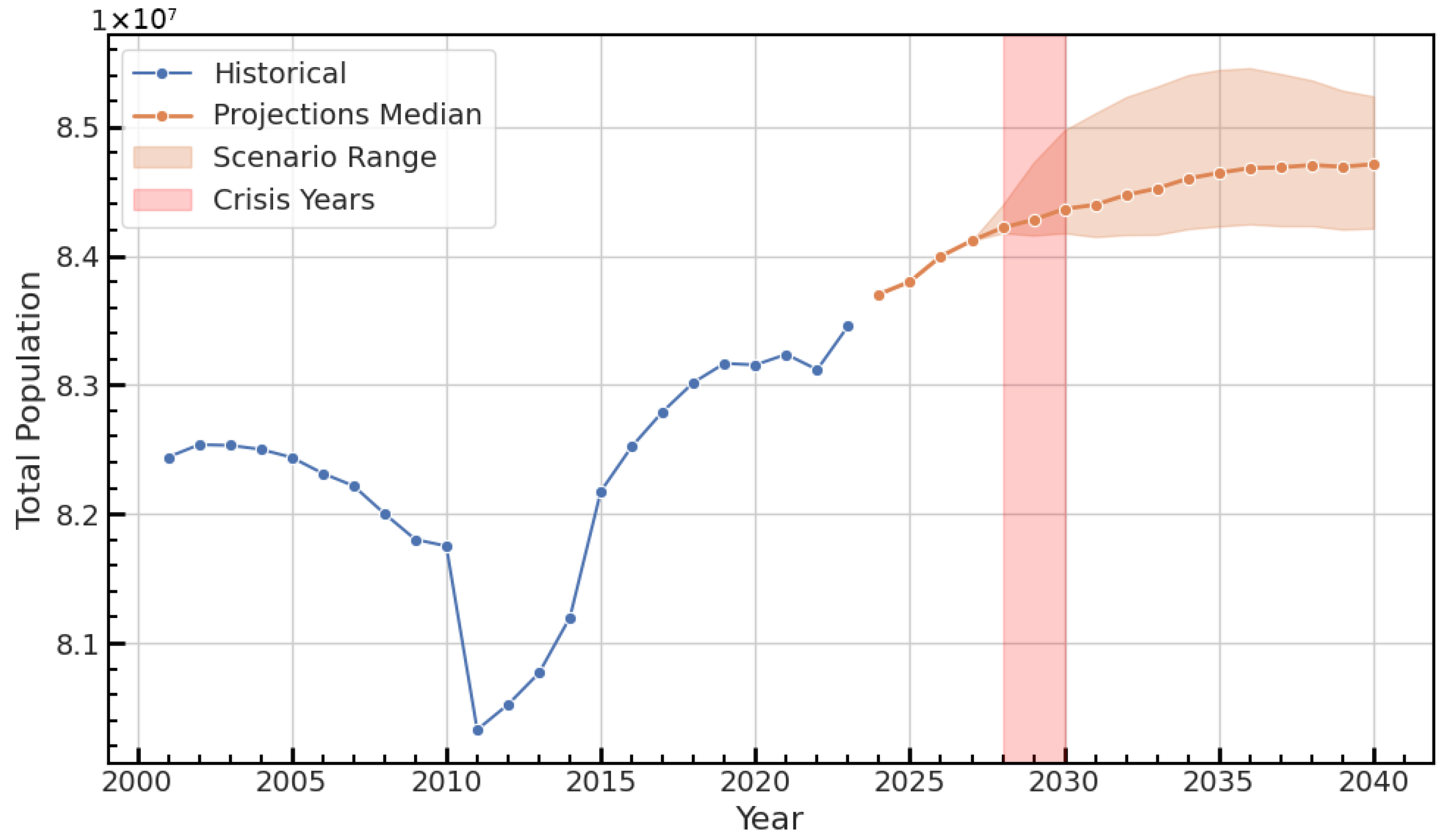

To illustrate how scenario flags lead to different futures, we present an overall visualisation for Germany (

Figure 13). The main line shows the median of all scenario projections, while the shaded area covers the lowest and highest values. This demonstrates how different crisis flags cause varying effects on long-term population outcomes, emphasising points where scenario design results in significant divergence. In this way, we depict model uncertainty through the range of plausible scenario-driven outcomes.

The magnitude of scenario-induced deviations depends inherently on the strength and persistence of historical signals in each demographic component. When past behaviour exhibits limited volatility, the ensemble naturally produces conservative adjustments that remain within historical variation. This behaviour is by design: it ensures that the model does not extrapolate implausible crisis responses in components for which no strong historical shocks exist. Conversely, where historical shocks are well-documented—such as in Germany’s migration series—the model produces more pronounced scenario-induced deviations. This feature reflects a fundamental principle of scenario-conditioned demographic modelling: responsiveness is anchored to known behavioural precedents, and caution is exercised when extrapolating beyond historically observed dynamics.

Taken together, the results show that the forecasting framework reliably reproduces recent demographic dynamics and translates historically grounded shocks into plausible future deviations. Scenario responsiveness is strongest where past crises left clear statistical traces, such as migration in Germany, and weakest where series are smoother or shorter, as in Portugal and Norway. Importantly, the ensemble balances stability and flexibility: it avoids overreaction in domains with little historical precedent, while preserving the capacity to project persistent effects of large shocks. The final section builds on these findings by examining their broader implications, assessing how methodological choices shape interpretability, and reflecting on the limits and policy relevance of scenario-based demographic forecasting.

5. Conclusions

This paper has presented a scenario-conditioned population forecasting framework that joins a standard cohort-component projection core with a simple regression ensemble for demographic rates. The key feature of the approach is that population futures are expressed as conditional statements: each forecast is tied to explicit assumptions about the occurrence of shocks such as pandemics, refugee inflows, and financial crises. Instead of extending past trends in an unqualified way, the framework embeds these scenario switches in the rate models and then propagates their effects through age- and sex-structured cohort-component projections.

Methodologically, the framework combines three elements. First, fertility, mortality, and migration rates are modelled through a robust Huber regression that uses short autoregressive histories, socioeconomic covariates, and binary event indicators. This allows the models to absorb information from past shocks while limiting the influence of outliers. Second, an exponential moving-average slope is used as a trend anchor, providing a simple and transparent way to stabilise long-run trajectories when data are sparse and highly autocorrelated. Third, lag selection is guided by decorrelation analysis, which limits the number of annual lags and avoids overfitting when only 15–20 observations are available for each cohort. Together, these choices keep the forecasting machinery deliberately modest, in line with the information content of official annual series.

The empirical application to Germany, Norway, and Portugal illustrates how the framework behaves in practice. Across these three cases, the model reproduces recent dynamics of fertility, mortality, and migration reasonably well and generates annual projections to 2040 under a baseline and three stylised crisis scenarios. A consistent pattern is that scenario effects are more pronounced where historical shocks are strong and recurrent, and weaker where past series are relatively smooth. For instance, Germany’s migration history includes clearly visible peaks associated with the Syrian refugee crisis and the war in Ukraine; when the refugee scenario is activated, the ensemble translates these precedents into higher future immigration, which in turn lifts specific working-age cohorts and the total population compared with the baseline. In Norway and Portugal, where shocks in the observed period have been smaller or less regular, the scenario paths tend to remain closer to the baseline, and the framework behaves more like a cautious trend extrapolator.

Another important finding is that the impact of scenarios depends on the level of aggregation. National population totals tend to absorb short-lived or offsetting shocks in fertility, mortality, and migration, so the differences between scenarios are often modest at this scale. Age-structured projections reveal sharper divergences, especially for cohorts directly exposed to migration surges or crisis-related changes in mortality. This is consistent with demographic intuition and suggests that the framework can be particularly useful for applications that rely on the composition of the population by age and sex, such as labour-market planning or health-care demand, rather than only on total counts.

The study also highlights the constraints imposed by short and imperfect data. With roughly two decades of annual observations, the temporal memory that can be exploited in a statistically meaningful way is limited. This motivates the use of robust regression and simple trend anchoring, rather than more complex machine learning architectures that would require longer time series or high-frequency data. It also affects the treatment of macroeconomic variables, such as GDP per capita and unemployment, which are modelled here in a parsimonious autoregressive fashion. In several of the experiments, these aggregates change only slightly across scenarios, reflecting the fact that the available annual data do not contain a strong and regular link between the binary crisis flags and macroeconomic fluctuations. From a practical point of view, this behaviour is preferable to inventing large swings that are not supported by the historical record, but it also means that the current set-up is not intended to capture the full richness of macroeconomic dynamics.

Several limitations follow directly from these design choices. First, the short sample length restricts the complexity of both the rate models and the validation strategy. Out-of-fold one-year-ahead evaluation is a reasonable way to assess performance in this setting, but it does not fully reflect uncertainty over medium and long horizons. Second, the ensemble tends to attenuate shocks that do not exceed past peaks, which is a desirable property for robustness but may understate the consequences of unprecedented events. Third, age grouping and measurement issues in official statistics, including census revisions and changes in migration definitions, can introduce discontinuities that are difficult to separate from genuine demographic signals. The framework mitigates this through robust estimation and smoothing, but it does not attempt to resolve all measurement artefacts. Finally, the models are not intended to be causal: coefficients are used for prediction and scenario conditioning, not for identifying structural relationships.

Within these limits, the framework offers a practical tool for stress-testing demographic projections in environments with limited data. By combining a familiar cohort-component backbone with a transparent regression ensemble and explicit event flags, the approach allows analysts to explore how different crisis narratives would play out in terms of age-structured populations, while keeping the modelling assumptions clear. The results for Germany, Norway, and Portugal show that this can be done in a way that is sensitive to the strength of historical shocks and yet conservative where the empirical record is quieter.

Future work can proceed in several focused directions. A first step is to move from binary event indicators to a simple description of shock intensity and duration, for example, by allowing graded values between zero and one and short persistence terms. This would permit richer scenarios, such as long, low-level crises or repeated waves of disruption. A second priority is to add a basic probabilistic layer, for instance, through bootstrap ensembles or regularised Bayesian regressions, so that forecasts can be accompanied by uncertainty bands at both cohort and aggregate levels. A third direction is empirical rather than methodological and concerns the extension of the framework to additional countries or to subnational regions where coherent annual data exist. Such applications would help to assess how far the present findings generalise and would make it possible to adapt the scenario design to different institutional and demographic contexts.

In summary, the paper argues that useful scenario-based population projections can be constructed from relatively short official series by combining simple, robust rate models with an explicit representation of crises. The emphasis is on clarity, internal demographic consistency and the ability to link qualitative narratives about shocks to quantitative trajectories. While the framework does not remove the fundamental uncertainty surrounding long-term population futures, it provides a structured way to organise that uncertainty and to examine how alternative assumptions about crises and stability might affect demographic outcomes.